Weird Tales/Volume 29/Issue 2/The Poppy Pearl

ThePoppy Pearl

By Frank Owen

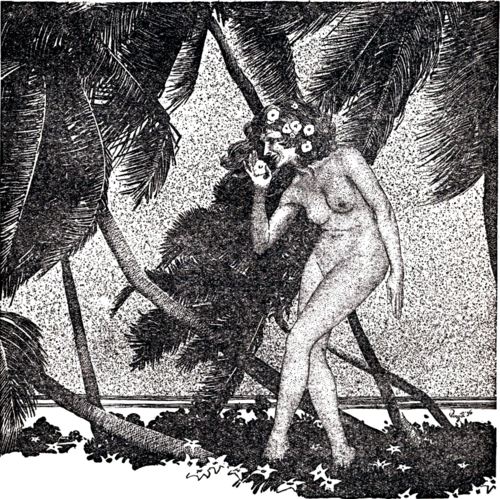

A glamorous, exotic tale of a wild adventure in the South Seas, an opium-ship, and a naked golden girl on a coral island

On the eve of his wedding Guy Sellers disappeared as completely as though the earth had yawned and swallowed him up. He was last seen leaving the Logue Club, where he had given a farewell dinner to a few intimate friends. It turned out to be more of a farewell dinner than anyone imagined.

It was six months before Gloria Lee saw him again. Then, as abruptly as he went, Guy Sellers returned.

"I have had an awful experience," he told her. "I have suffered torture." He shuddered as he spoke and drew his hand across his eyes as though he would blot out the sight which his memory conjured up for him.

She placed her hand upon his arm. "If it makes you feel so bad," she said softly,"do not speak of it."

"I must," he cried. "After the way I have treated you I owe you an explanation. The story I have to tell is so odd you will scarcely credit it."

Again he hesitated for a moment before he continued.

"After I left the boys that night at the Logue Club I decided that I would walk home. It was a charming evening and I set off at a brisk gait up Fifth Avenue. Although it was not much after midnight, the avenue above Sixtieth Street was almost deserted. Suddenly I gazed down a side street and saw the figure of a man lying by the curbstone. At once I went to his assistance. As I did so a veritable giant of a man came forward also.

"'We'd better get a cab,' he said, bending over the prostrate form; 'this fellow seems to be pretty well knocked out.'

"Even as he spoke, a taxi drew up alongside the curb; which somewhat surprized me, for neither of us had summoned one. The next moment we had lifted the man into the taxi. Then an unexpected thing happened. He suddenly came to consciousness and springing to his feet, pressed a handkerchief over my mouth. Meanwhile the other threw his arms about my body, pinning me down until I was helpless. At the same time there came to my nostrils a peculiar though not unpleasant odor, and I grew very tired. My eyes closed in spite of all my efforts to stay awake. I was well aware that I was in a most precarious position, that I was being doped and carried away. Yet sleep came to me and I did not care.

"When I awoke, everything was as black as pitch about me. I had no idea where I was. In a panic I put out my hands in all directions, but I could feel no walls. I rose to my feet and started to run in the blackness, as though by so doing I could shake it off. The floor rose and fell as though it were moving. Twice I almost fell, and once, unable to save myself, crashed to the floor over some protruding object and struck my head a stunning blow. At that moment there came an unearthly shriek and something cold and dank brushed against my hand. It seemed as large as a cat, although of this I was not sure, for in the blackness only its shining eyes were visible.

"With a cry I sprang to my feet and stood trembling, afraid to move. The floor rose and fell rhythmically. Without doubt I was on a ship, a ship infested with rats and other vermin. For what reason I was imprisoned in that gruesome hold I did not know.

"I was interrupted in my musings by a ray of light which appeared above my head. The next moment a hatch had been removed, and far above I could see the blue of the sky. By the position of the sun I knew that it was nearly midday. I had evidently been unconscious for many hours.

"And now there appeared the most peculiar-looking individual I have ever beheld. He dropped down into the hold as though he were a gorilla, not deigning to use the ladder. His face was repulsively ugly. His eyes, wide apart, were separated by a nose so broad and flat it was simian. His protruding chin resembled a cup, a great wart underneath taking the place of a handle. His mouth was enormous, as though it had been slit from ear to ear in infancy, just as was done in

Old Paris to make permanent grinning jesters for the kings. But the eyes were the most repulsive feature in the face. They were as small as those of a hog, and rheumy rings of inflammation encircled them. For a moment this monstrosity of a man stood and surveyed me as though I were some new species of insect.

"At last he spoke, and his voice was as great a shock to me as his appearance. There was a note of culture in the tone, and he pronounced his words perfectly.

"'My name is Jolly Cauldron,' he said, 'and I'm captain of this ship. You re one of the new hands, and you're going to do as I say.'

"In the tone there was no animosity. He simply took it for granted that I would bow to his wishes. Naturally I rebelled against this.

"'I refuse to be treated like a dog,' I told him.

"He threw back his head and laughed heartily, as though I had told him the rarest joke. But as quickly as the fit of merriment seized him it passed, and his eyes narrowed until they were only points. The next moment his arm shot out, caught me on the tip of the jaw and sent me sprawling in a limp heap a dozen feet away. At that moment, mercifully, darkness closed in again. As consciousness slipped from me I seemed to hear Jolly Cauldron's laugh echoing as from a great distance.

"How long I remained unconscious I do not know, for the next thing I remember was my head throbbing as though it would burst. My tongue was parched, and my body burned with fever; yet on my brow was not the slightest sign of moisture. My flesh was baked dry. Over my body countless rats scampered. They paid no more attention to me than if I had been part of the flooring. I was stifling. All air seemed to have been sucked from that hold.

"Again the hatch opened and Jolly Cauldron climbed down the rope ladder. He carried a jug of water and a bowl of food. Although it was composed of boiled pork and greenish potatoes, to me it looked appetizing.

"Jolly Cauldron kicked me in the chest. 'Well, how's the dog?' he cried.

"He placed the food and water on the floor a short distance from me. I tried to rise but could not. I was chained to the floor.

"'Until a dog's well trained,' grinned Jolly Cauldron, 'it's a wise precaution to keep him tied up.'

"That hour was one of intense agony. Jolly Cauldron left the hatch open so that I could be a spectator of the events that followed. The rats came out of the darkness in swarms and attacked the food. In their haste and gluttony they even attacked one another. My tongue was hanging out. I'd have committed any crime merely for the privilege of wetting my lips.

"Jolly Cauldron returned and shook his fist at me. 'What do you say, dog?' he cried. 'Are you willing to obey me now?'

"In a voice that was almost a moan I admitted that I was, so he released me and led me up the hatchway to the crew's quarters. A more filthy place could not have been imagined. The cabin was swarming with vermin. The floor was covered with litter, chunks of biscuit, empty beef-tins, bits of decaying pork and wads of tobacco. Yet to me after my confinement in the rat-ridden hold it was not repulsive.

"In the days that followed I learned quite a bit of seamanship. I was on a four-masted schooner, The Poppy Pearl, and we were bound for China. The crew were opium-smugglers Jolly Cauldron held them on that ship with a force as strong as bars of iron. Every member of the crew was an opium fiend and each night, in lieu of pay, he received a little round pellet of the drug. I wish I could describe the weird character of those nights. The forecastle reeked with opium fumes. Usually I slipped into slumber, into a semi-stupor with the sweet deadly perfume in my nostrils. Sometimes I would have the wildest dreams. I walked on the bottom of the sea through caverns filled with gold and jewels. From such fantasies I disliked to awaken, for I always rose with a nauseating taste in my mouth. As I strode to the deck I used to glance at my drug-ridden companions. There was a look of profound repose on every face, even though crawling things were gliding unmolested over the inert forms.

"Much happened on that ship that I should like to relate, but if I did it would be like singing an endless, mournful chantey of the sea. Day followed day, week followed week in utter monotony. On all that ship there were no two men who trusted each other, no two who were even casual friends. They had known all the horrors and hatreds of life, and their faith in things was utterly shattered. Gradually I grew as crafty as the rest. I fawned over Jolly Cauldron, became a thing of the most despicable hyprocrisy.

"Far from pleasing him, my new attitude made him hate me the more.

"'I had thought,' he snarled, 'that you were a thoroughbred. But I was wrong. You're just a mongrel, utterly worthless.' But a day was to come when Jolly Cauldron placed his faith in me above any Other man on the ship.

"It all came about because Slim Williams went mad. It was on a certain day after we had been at sea for several months, while we were sailing slowly through the Yellow Sea. For more than a week the temperature had been over a hundred and the humidity was so high we could scarcely breathe. At best Slim Williams was feeble mentally, and when the constant glare of the sun fell upon him, his mind broke completely. He imagined that he was extremely religious, that he had been sent to save The Poppy Pearl from destruction. He crept stealthily down into Jolly Cauldron's cabin and seized the steel-bound chest in which the opium was kept. Staggering under its great weight, he returned to the deck. Before any of us could stop him, he had hoisted it over the side and it splashed out of sight into the Yellow Sea.

"Never have I beheld such a frightful expression as was on the face of Jolly Cauldron at that moment. His mouth worked convulsively as though he were having a fit, and his face was gray-white. The inflamed circles about his eyes were red, as red as raw flesh. The next minute his great arms had closed about Slim Williams with such terrific force we could hear the bones crack. Slim moaned slightly and frothed at the lips. For a few seconds only Jolly Cauldron held him thus; then, uttering a long, harsh laugh, he pitched him headlong into the sea. As I stood at the rail I could see the gruesome shadows of sharks circling the ship.

"That night was the hottest I have ever experienced. There was not a breath of air stirring. The water glowed with a peculiar yellow light, caused no doubt by some phosphorescent sea-anemone, but to me it seemed weird and ghastly. In the forecastle the men lay on their bunks, panting for breath, cursing and screaming for their day's pay of opium. A single oil lamp swung from the rafters overhead. The feeble flame of it made the shadows all about us more pronounced. Never have I heard such cursing as I did that night. The fiends were raving for their drug. Without it their nerves ripped like rotted threads.

"Jolly Cauldron summoned me to his cabin.

"'They're all mad,' he cried and he forced a revolver into my hand, 'Only you and I on this ship are sane. The rest are merely beasts. If they try mutiny we'll shoot them down. It'll be our lives or theirs.'

"For the remainder of the night I crouched in the bow of the schooner. All about us yawned the blackness of death. The humidity was so heavy it formed a veritable mist. We could not see the stars. The moon had not yet risen, and in no direction was there any sign of light save that phosphorescent glare on the waters. The sails hung limp from the yards. We scarcely moved. And as I sat there, despite the weirdness of the night, I dozed. I dreamed that a figure was creeping upon me.

"With a start I opened my eyes. Directly over me stood the gaunt figure of a man. Now the moon had risen and the mists had cleared. It shone on the uplifted blade of a knife. I had no time to reach for my revolver. Spellbound I gazed into the sinister face beyond the knife. It glistened madly in the eery light. Then a shot rang out and the horrible face writhed in agony. Out of the shadows Jolly Cauldron appeared.

"'Can't even protect yourself!' he sneered; 'merely a worthless mongrel.'

"The following day we stopped at a tiny island, peopled entirely by Chinese. Jolly Cauldron wished to renew his opium supply. So intent was he on his mission that he momentarily forgot my existence. In the excitement I ran away and hid in the hills well back from the coast. Hours later, from a secluded position on a high cliff, I watched The Poppy Pearl slip out to sea. She looked very beautiful with all her sails set, racing before the wind. Nothing in her appearance suggested her true character.

"Toward evening that same day I was able to book passage on a Chinese junk bound for Canton. Although the accommodations were far worse than those of steerage passengers on trans-Atlantic liners, I found no fault with them. At least the crawling things were there in fewer numbers. In due course we arrived in Canton, ancient city of mystery, where the East and the West rub shoulders. A few days later I caught a steamer for Shanghai, where I connected with a liner bound for San Francisco. I was on my way back to America and you."

2

Ten days after his arrival in New York, Guy Sellers was married to Gloria Lee. They had given up their plans for a big wedding and only a few intimate friends were present. For their honeymoon they went to England, to a little house in Stanbury Downs far off the beaten track of travel. It lay nestled in a charming garden like a mushroom in the heart of the woods. Mother Grimes, who kept the cottage, was a delightful little old woman who seemed to anticipate their every want.

"I think we should pass up London absolutely," declared Gloria, "and just rusticate here. I'm sure no other spot in England could be more appealing than this."

And yet they did visit London, where, like hordes of others, they were enthralled by the "charm of the antique," the steeples of Sir Christopher Wren, stately Westminster Abbey and legendary London Tower, not to mention the friendly little coffee-houses tucked away in the most outlandish spots and hidden corners as though they were jocularly playing hide-and-seek with one another. They left London with regret, although they rather looked forward to the peace and quietude of Stanbury Downs.

Then as abruptly as happiness came to them, it was shattered. Without warning, Guy disappeared again. For a week Gloria remained at the little house, but he did not return. So at last she sailed for New York.

In Gloria's mind doubt was taking root. It seemed unnatural for Guy to disappear twice so mysteriously. She was not worried—she was annoyed. In New York she consulted her lawyer, who in turn got into touch with the best detective agencies, but not the slightest trace of Guy could be found.

Thus five months rolled by and then again he returned. He was very thin. His clothes hung upon him like sack-cloth. If he noticed that Gloria was rather cool in her greeting he did not show it.

"Once more I have had a most peculiar experience," he told her. "As I walked down Hambleton Road that day in Stanbury Downs I came upon an old woman seated in a carriage that looked as though it might have been the first one ever made. She was driving a horse so thin that it seemed ready to fall apart. Only the skin held its bones together. I am sure that had it not been for the shafts it would have fallen. The old woman was calling shrilly to someone in a cracked querulous voice. I glanced about, and as there was nobody in sight I assumed she was calling to me. So I strode over to her.

"'Please come with me,' she implored; "my good man is ill and I think as ow 'e is dyin'. I'm so 'fraid. 'Tis a doctor I wish to be goin' for but 'e lives a good ten miles away an' I cannot leave the good man for long.'

"Although I was not at all impressed with the crafty-looking old woman, I clambered into the carriage beside her. As we went along she kept up a babbling chatter which was very irritating. I was bored to death and anxious to get away, but I was bent on an errand of mercy and so I stifled my boredom.

"We rode into the hills through endless winding roads, and I wondered why the old dame had not gone at once for a doctor if she had been able to leave her 'good man' for such a long period. Then I reasoned that although we had seemed to be on the road for a great while we had perhaps ridden only a few miles, for our horse just sauntered along as though bound for no place at all. But at last we arrived at an immense house in the center of a wood. It was falling into ruin and appeared deserted. The porch sagged at a perilous angle. One end of the roof had caved in. Most of the windows were broken and the chimney was a wreck. Although the building had probably once been quite pretentious it was now ugly. The dull gray boards held not the slightest remainder of paint. Nor was the house the only thing of ruin, for the barn had utterly fallen in, a com-crib near by was about to collapse and the fence in front of the house was down and half buried in the mud. The remains of an unkempt garden grew about the door, a few straggly bushes and a tangle of grapevines almost submerged in weeds.

"The old lady laboriously climbed down from the carriage, though not without a good deal of puffing and muttering of invectives which, though they were gibberish to me, created an unpleasant impression.

"''Ere we are,' she muttered, 'an' it do be good to be back.'

"She led the way into the hall. It was even more dingy than the outside of the house, a place of shadows. I could scarcely see my way about, but the old woman made no attempt to light a lamp. She seemed unaware of the gloom. She moved as sleekly as a cat, as though she could see clearly in the darkness. Upstairs she led the way, and as we ascended it appeared to grow even darker. I noticed that pieces of heavy brown paper had been nailed over the broken windows. We climbed another flight and now it was like night. I groped my way along, unable even to see the old woman. I just followed the direction of her voice, for she kept up a continuous stream of conversation.

"'Jus' one more flight,' she mumbled. 'Ah, 'ere we are.'

"As she spoke she threw open the door of a room. The hinges creaked as loudly as though they had been unused for a century, but at least the room, despite its dimness, was somewhat lighter than the hall. It was of immense size, almost as large as a hotel lobby. It contained enough furniture to start a store. Evidently it wTas an attic storeroom, for the stuff was heaped up almost to the ceiling on every side. It was certainly a miserable room for a sick man to remain in.

"He lay upon a huge old-fashioned bed in a corner, moaning slightly. In a moment I was by his side. As I bent over him I received the shock of my life. I was gazing into the smiling face of Jolly Cauldron. Instantly I turned and rushed to the door. It was locked. But even as my hand closed upon the knob, Jolly Cauldron was upon me.

"He smiled like a wild thing as he sprang, and together we crashed to the floor. Meantime the old woman, her work accomplished, had disappeared. At that moment something seemed to treble my strength. I felt as though I were fighting for my very life. I crashed my fist into jolly Cauldron's face. I rained blow after blow at his body, but though I struck with all my force he simply looked into my face and laughed.

" 'Keep it up, dog,' he sneered, 'and when you are tired, I'll beat you into submission.'

"His great arms closed about my body. I recalled how he had crushed Slim Williams. It was exactly as though I were held by a mighty octopus. The arms grew tighter. I was being crushed alive. I pleaded for mercy, I begged to be released. But still he laughed. Still that frightful force continued. Unconsciousness came at last and I grew limp in his arms.

"When I opened my eyes again I was aboard The Poppy Pearl and we were rapidly slipping out to sea. I sat with my head propped against the gunwale. It was a lovely day, with breeze enough to carry us along as smoothly and gracefully as though we were aboard a yacht. Near me stood Jolly Cauldron.

"'It's rather good to have you back,' he chuckled."

As Guy paused for a moment in his narrative, Gloria placed her hand upon his arm.

"Please do not tell me any more," she said, and her voice was cold and lifeless.

Guy glanced up quickly. "What do you mean?" he cried.

"Merely that I do not believe your story," she answered calmly. "My lawyer has been working on this case for months with the aid of the best-rated detectives in town. We have learned that the schooner Poppy Pearl does not exist and never did exist. I do not know where you have been, nor do I care. I intend to get a divorce from you on the ground of consistent desertion. There are states where such a charge is permissible. I am sorry that this has happened. It has rather wrecked my faith in things."

That night Guy Sellers booked a room at the Logue Club. His head was in a whirl. The words of Gloria had stunned him. Her declaration that The Poppy Pearl did not exist and never had existed was amazing. He walked up and down the room as though he were in prison. He questioned his own sanity. All that had happened to him seemed wild now as he viewed each scene in retrospect. If the stories he had told were untrue, where had he been during all those months? Had he been a victim of amnesia? He decided against this theory because there had been no break in the continuity of his experiences; each had dovetailed perfectly into the others. His memory of everything that had happened on those voyages was utterly clear.

Hours passed. He took no thought of time. Piece by piece he tried to fit together that jigsaw puzzle. It was vital for him to prove that his story was not fictitious, to prove that he was not going mad. Unless he could find some trace of The Poppy Pearl, he believed that his mind, if not already deranged, might become so.

Finally he could bear the oppression of his room no longer. In desperation he went downstairs to the library. He wanted to escape from himself. Before the fireplace he found his greatest friend, John Steppling, who looked up lazily as Guy entered. In a few words Guy told him what had happened.

"And now," Guy finished, "I've lost Gloria. You can't appreciate how frightful are my feelings. I'm utterly wretched. Without her, life is useless."

Steppling said nothing. He let Guy talk, well knowing that the best way to suppress any emotion is to give in to it.

When Guy paused, he said calmly, "There never was a problem that couldn't be worked out. At the moment the main thing is for you to think clearly. Don't give way to nerves. Adopt a definite course of action. For example, you could trace your wanderings backward. Start at your arrival in New York."

"I came from Singapore on the steam-ship Caliph to San Francisco, thence by Santa Fe and Twentieth Century to New York. I worked my way from Singapore as one of the crew. When I arrived at San Francisco I wired my father and he sent me funds. His telegram is proof that I was in 'Frisco. The ship's records will prove that I came from Singapore. But past Singapore I cannot trace my wanderings, for it was there that I deserted The Poppy Pearl. I'm afraid that there is only one thing for me to do. I must find Jolly Cauldron."

During the following days he passed his entire time loitering about the waterfronts, frequenting the resorts of longshoremen, eating at cheap coffeehouses, and always he made it his business to get into conversation with the seafaring men, who usually were quite willing to talk. But ever the answer was the same.

"The Poppy Pearl? Never heard of her. Perhaps you've got the wrong name."

On one occasion he sat at a table in a café beside a rugged old man of the sea who looked as though he might have been Father Neptune in disguise.

"Never heard o' The Poppy Pearl," he drawled, "but maybe I'd remember her cap'n. Know his name?

"Jolly Cauldron," replied Guy.

The old fellow chuckled softly to himself, and somehow Guy had the uncomfortable feeling that he was being held up to ridicule.

"Jolly Cauldron," explained the old man, "was a smuggler. He was lost at sea more than ten years ago. If you're lookin' for him you'd better sail for Europe and then jump overboard when you're half-way across."

At this point another old mariner cut into the conversation.

"Murty," he said disdainfully, "your memory's clogged. There was a smuggler lost, but his name was Johnny Caldwell."

"You're wrong," snorted old Murty. "I never forget a thing. Got the best memory above decks. 'Twas Jolly Cauldron. I'd stake my last dollar on it."

Guy left the café in a daze. More and more he questioned his own sanity. After all, what is the dividing line between sanity and insanity? The wild line of the docks which he frequented like a grim specter did not serve to make reality any more clear-cut. He walked wearily up West Street. At that moment he was more confused than ever. If old Murty was right, how could he explain his uncanny adventures? Although it was broad daylight he seemed to be groping about in the dark, trying to find his way blindfolded. He had no idea how to continue his search. So he walked along, his hands in his pockets, his gaze upon the ground, when suddenly someone slapped him on the back.

"What's the matter, dog?" a voice cried; "are you looking for your bark?"

There could be no mistaking that voice, nor the infectious laugh that accompanied it. He glanced up eagerly into the face of Jolly Cauldron.

"Are you a ghost?" he murmured.

"Perhaps," was the reply."If I were I'd be quite at home in New York, for is not this a city of shadows? However, I'm glad I met you, because we sail in half an hour. Even to a ghost, time is of value."

As Jolly Cauldron spoke he seized Guy's arm in his great steel fingers and hustled him along the waterfront to where The Poppy Pearl was berthed. Had he but known the truth he need not have been so imperative in his manner. There was nothing Guy wished for more than to sail again on that phantom ship; for so he was beginning to think of it.

When the tide turned, the schooner drifted out to sea. Guy stood in the stem and watched the city fade into a maze of humid mist. At that moment the city itself seemed wraith-like, the tops of the buildings melting into the clouds. Gradually, as the sails caught the wind, the schooner sped on and on, as though glad to be free, until the buildings seemed to verge into the mist, vanishing completely.

At last Guy had achieved his most ardent desire. He was back on The Poppy Pearl, and now as he trod the worm-eaten decks, the ship was far more real than the city which had just faded into the clouds.

There followed weeks of hard work, endless days of toil and nights in that insect-infested forecastle where the men cursed and sang ribald songs to pass the sluggish hours, nights when Guy believed the ship was in truth an eery thing of another world. He often sat by the hour on the steps leading to the deck, mulling over his problems. If these men were phantoms, then he was a phantom, too, for they ate the same food as he, slept in the same filthy quarters, worked on the same endless round of jobs. After all, what was reality? Were the people in New York and London real? Was anything real?

3

One night there was a frightful storm. Guy woke with a start from a troubled sleep, dimly conscious that some brooding peril hung over the ship. For a while he lay on his bunk trying to collect his wits. The hanging oil lamp sputtered dismally and swayed as though it were on the verge of falling. He gazed intently into the appalling shadowy corners. He alone in the forecastle was awake. The others were too stupefied to be aroused by such mundane things as storms.

The wind shrieked as though all the discord of the universe had been released at once. It drowned out every natural sound, and yet almost like a dream-echo, above the chaos there came a cry, a human cry as though someone were being mangled by the fearful noise.

Guy sprang to his feet. In a moment he was on deck. By the feeble light which filtered up from the forecastle lamp, he beheld Jolly Cauldron choking little Wu, the Chinese cook. As his great fingers closed convulsively on the yellow scrawny throat, Jolly Cauldron was singing a frightful threnody of gloom.

"You see, Mr. Wu," he said, "at your funeral there is music, although I apologize for the absence of flowers. However, in a few moments you will be able to twine some flora of the sea into your queue; for I am going to show you the way to the gardens of the sea."

Perhaps it was the wildness of the night which made Guy Sellers cast all caution to the winds, but whatever the cause, he sprang at Jolly Cauldron with such force that by the impact Wu was released from the relentless grip. However, it was only for a moment that Guy had the upper hand. Against the power of Jolly Cauldron he was impotent. In less than a moment he was lying half dazed on the deck as a result of a ponderous blow on the mouth, completely subdued. Jolly Cauldron stood over him and grinned.

"Under the circumstances, dog," he Said, "I guess I'd better put you back into your kennel."

While speaking he walked over and (opened the forward hatch; then with supreme ease he lifted Guy up in his arms and flung him down into that yawning pit of blackness which was the hold.

For a long time Guy lay scarcely conscious. His head ached dully from the thud of his fall. His mind was confused. He could not remember things clearly. Where was it he had fallen from? And where was it he had fallen to? He was on the verge of delirium.

Then, without warning, there came a deafening crash, accompanied by a ripping, snapping pandemonium as though the old vessel were being torn to pieces by ruthless giants of the sea. Although Guy was lying flat on his back in the pitch-black hold, at the dreadful impact he rolled more than a dozen feet as if he had been a hogshead. The ship moaned and groaned in every beam. Huge rats ran over him in screeching hordes. They swept past him like armies plunging into battle; although that is not strictly true, for they were wild with terror, more like a vanquished army in ignominious flight. They paid no more attention to him than if he had been a block of wood as they scrambled screeching horribly over his body. He threw up his arm to keep their cold, dank feet from gouging out his eyes. He made no effort otherwise to escape them, for escape was impossible. With preterhuman instinct, the rats were fleeing from a doomed ship. The old vessel was grappling and groveling in the agony of death. "The Isle of Lost Ships" was ominously calling to her. Every board vibrated with the intensity of her motion; for a ship has a personality, a soul, as surely as a human being. And now she was dying, though not without a gallant fight against death.

Guy was fully conscious now. The shock had swung him back into complete rationality. His brain worked doubly fast, as though striving to make up for its previous sluggishness. By sheer force of will he kept himself from succumbing to panic. His only hope lay in clear thinking. He knew his position was grave. Evidently the ship had struck a half-submerged rock or a coral reef somewhere in the South Seas, the most treacherous and at the same time the most beautiful waters of the world. Where the vessel was foundering the water might be three feet deep or a mile. If a mile he would go down with the ship, be virtually buried alive, assuming that the hatch would hold water-tight. He thought of all the fantastic tales he had read of premature burial. Now he was living a story as terrifying as any by Edgar Allan Poe. There was no hope for him; he faced a lingering, suffocating death with perhaps complete madness before the ghastly end.

He pictured himself lying dead, with the few ravenous rats that had failed to get away gnawing at his flesh. Cold perspiration stood out on his forehead. He rose to his feet. The floor sloped at such a perilous angle he could scarcely stand. He groped his way along the walls. There was not a crevice anywhere through which even the faintest draft of air could filter.

Then unexpectedly there came a grating sound. The hatch was drawn back and Jolly Cauldron's voice bellowed out harshly above the wailing of the storm, "Here's a ladder, dog. Get out! You've got a chance to live if you can swim."

Guy Sellers fumbled about in the darkness until his hand came in contact with the rope ladder. He whined like a frightened animal as he seized it and began to ascend. He was saved, not from death definitely but at least from the frightfulness of a rat-infested tomb.

In a few moments he was on deck. It was still as black as the hold. The night was so thick that water and sky and air all merged into one limitless opaque mass of blackness. The rain drove down like chips of steel. In that gale no lantern could have survived. He seized a rope to keep himself from being swept overboard by the monstrous seas which constantly planed the deck. He did not know what had happened to his companions. They might have been standing beside him unnoticed in that impenetrable blackness. It was uncanny, the piercing, deafening crescendos of the elements, and yet not a single human sound.

How long he stood motionless, he did not know. It might have been hours or it might have been only minutes. In great moments, moments of awe or terror, time becomes abnormal. It grows to monstrous size or shrinks into insignificance. Time at best is absurdly indefinite.

Guy gasped for breath as a great wave crashed over him. He lost his grip on the rope ladder and was swept along, struggling futilely. He clutched frantically at the rail, but his fingers closed only on air. He tried to regain his feet, but the deck was so wet and slippery he fell before he had even risen to his knees. He cursed in despair. At that moment there came a wave so huge that as it broke above the ship it must have towered higher than the masts. It curled over and broke with a terrific roar. As it fell it seized Guy bodily and cast him into the whirling sea. Mercifully as the full force of the wave struck him he was stunned, and again his senses slipped from him like a cloak.

When he opened his eyes, he was lying on a white coral beach. It was morning. The storm had passed. The weather had swung to the other extreme, as is its habit in the tropics. In the dazzling brilliance the waters shone as though they; had become a sea of liquid gold.

Guy sat up and gazed stupidly about him. There was not the slightest vestige of a human being anywhere in sight, nor any sign of habitation. About two hundred yards from the beach The Poppy Pearl clung perilously to a reef, her stern far out of the water, her bow almost submerged. During the night she had been badly buffeted and now she showed painfully the scars of her lost fight. All but one of the masts were gone, her stem was stove in, and, to judge from the position in which she lay, her rudder was lost. She appeared deserted, her ugly black hulk standing out like an obscene blot on the beauty of the morning.

Guy rose to his feet. He walked up the beach away from the water. There was a fringe of palm-grove which he decided he would explore. It was carpeted with fallen coconuts which had been blown to the ground by the storm. With the side of a jagged rock he tore away the husks and broke one open. The milk was deliciously sweet.

"To be shipwrecked on such an island," he reflected, "is certainly not a hardship. I have tumbled into Eden. If it weren't for Gloria I wouldn't mind spending a year here."

In the grove behind him he heard a great commotion as though some animal were approaching. The next moment Jolly Cauldron appeared from among the trees. He was grinning broadly.

Guy was both surprized and glad to see him. "Where did you come from?" he gasped.

Jolly Cauldron waved his hand vaguely toward the jungle of palms. "Over yonder," he said. "I'm not very familiar with the neighborhood because I only moved in yesterday. But from a casual survey of the surroundings I think I'm going to like it."

"I can't understand how you happened to be among those trees," declared Guy, "It is remarkable."

"Not at all," was the reply. "When I was washed overboard I merely swam to shore. There was nothing extraordinary in my accomplishment. It was not necessary to swim any great distance, and besides, the waves helped me. They washed me in, just as you were carried by them up on the beach like a dead fish. For a few moments after I found you I tried to awaken you from the stupor into which you had fallen, but without success. You refused to be aroused. So I thought I'd saunter about the island for a while and get a line on our chances of finding happiness."

"Have you any idea where we are?" asked Guy.

"I believe on a coral island, although those distant mountain peaks suggest a volcanic origin. How far we are from the next link in the chain I do not know. We may have to stay here a year, and then again we may be able to leave before sunset. Personally I lean toward the year. Fortunately The Poppy Pearl is lying in shallow water. With care we can wade out to her along the coral reefs without getting into water much above our waists. But we've got to be careful to stick to the reefs, because if we don't we'll be in water so deep only sharks will ever find us. Even on the reefs great care must be taken. If we cut our feet we're liable to develop sores that'll never heal, stay open festering for years. Coral is like women, sometimes very beautiful, at other times very dangerous. When we get out to the ship it'll be a very easy matter to rig up a line and tackle. On second thought, I'll go out to the ship alone. I'm more familiar with the line of work. You can remain on shore and unload the tackle. It will be a simple matter to transfer enough food and supplies to last until this island is in a flourishing state. By the way, dog, shall we bring some vermin off the ship also, so we'll feel at home?"

Never in his life had Guy attempted such arduous tasks, not even on board The Poppy Pearl, as crowded the next few weeks. They worked from dawn till dark transferring supplies from the ship. They took everything that could possibly be of use to them, provisions, clothes, tools, ropes, sails and even stray bits of the wreckage. Jolly Cauldron was tireless. He worked as hard as he had ever driven his men. His faults were legion, but laziness was not among them.

When all the cargo from the ship had been piled up on the beach, well out of reach of the surf, they set about erecting huts out of the stray bits of wood and pieces of mast. They thatched the roof with palm leaves, held in place by strong ropes and covered with tarpaulin. Jolly Cauldron, after years at sea, was an expert carpenter, and it was he who did the planning.

As time wore on, Guy had an excellent opportunity to study Jolly Cauldron. Guy had long since given up the idea that he was a phantom. He was as real as anybody, more real than most people, for he had individuality. A great many people are merely copies of somebody else.

Jolly Cauldron scoffed at everything, even though he was surprizingly well educated. Guy was a college graduate, and yet Jolly Cauldron's knowledge on many subjects far eclipsed his.

Once he said to Guy, "I can speak seven languages and it doesn't appear as though on this island I'm going to need more than one. What a dreadful waste of knowledge!"

For the first few days of their exile he was in a rare mood. Among other things, he showed Guy the log of the vessel.

"I prize this highly," he said, "because I want to take it to Liverpool to support my insurance claim."

As Jolly Cauldron spoke, Guy glanced at the name on the log-book, "The Golden Glow."

Jolly Cauldron noticed his surprized expression.

"The Poppy Pearl," he exclaimed, "is registered in Liverpool as The Golden Glow. She merely goes by the name of The Poppy Pearl when we are smuggling opium because she comes of excellent family and her folks would feel very bad if she went astray. I think you will admit that it was a wise precaution for me to keep changing her name at my convenience. Sometimes she was The Poppy Pearl, sometimes The Golden Glow. I always carried two log-books with me and an extra forged set of ship's papers. Am I not somewhat of a genius? You see, dog, you're learning something from me every day."

He paused for a moment, then continued musingly, "She was a beastly ship. I always wanted to wreck her but couldn't. When I abandoned my efforts, nature took them up. Now she lies on the reefs, her back broken, a total loss; or rather a total gain, for I had her overinsured and my profit will be enormous. Glance at her, dog, and let your poetic spirit have free sway. Can you not write a sonnet about her, a great black pearl strung on a necklace of coral?"

Of all the crew of The Poppy Pearl, only Guy and Jolly Cauldron had safely reached the island. Many of them had been swept overboard during the gale, while those who had been down in the forecastle, steeped in opium, had been drowned like rats as they dreamed of Manchu princesses; for the forecastle had dipped under water and when Jolly Cauldron fought his way into it while securing the supplies, even he had sprung back in horror at the ghastliness of the sight. Now that the vessel was firm on the reef the water had seeped out again, leaving the dead men covered with bits of seaweed and sea-flora. They lay on their bunks, their putty-white faces grinning like fiends. Grimly, one by one, he carried them up to the deck and cast them into the sea. The sharks circled about the vessel in schools. They must have thought that it was feast-day.

4

Had it not been for one rift in the lute, life on that island would have been one roundelay of enchantment. The rift was the utter monotony of existence. It was like gazing for ever at the same perfect picture. A sea of azure blue, a sky of ever-changing, ever-charming glory, palms that stood out against the distant hills as clear-cut as cameos. But over all hung a web of silence that was maddening. On the island there was not a living animal; at least none had ever come within the range of their vision save a few giant crabs that haunted the groves like ghouls. But they were not like living things.

Sometimes Jolly Cauldron sat late into the night talking on desultory subjects. More often he lay on the beach and smoked a small black pipe.

"With this pipe," he cried, "I can find all the friends man could desire in the space of a few brief moments. Why do you not join me and we can journey into Elysian Fields together? In time, monotony, especially in the tropics, will sap the vitality of any man. Knowing this, I am making every effort to guard against it. We may be on this island the rest of our lives. You are young. You may live forty years. Can you imagine forty years of unescapable monotony?"

Guy made no reply. He refused to heed the advice of Jolly Cauldron. In its very logic it was sinister. Night after night he sat alone, gazing wistfully out over the sea. In the moonlight the coral-sand glowed whiter than ever. Sometimes he strolled along the beach in an endeavor to break the awful monotony of never-ending hours, but he could find no solace. Even his footfalls were soundless.

By day also the monotony was maddening. On the island there was not even a single bird; at least, neither Guy nor Jolly Cauldron had ever seen one. Jolly Cauldron cared not at all, but Guy was a high-strung individual. The continued calm of the island made him melancholy. At last he gave up his walks in the moonlight. He merely crouched on the beach like a thing of stone. He grew haggard, and his face became the color of old ivory.

One morning he rose at dawn and walked slowly along the shore, as though impelled in his course by some strong hidden force. His body seemed without weight. His feet lifted from the ground without effort. When he talked, no sound came from his lips. He was untrammeled. He was free. He capered along the beach like a merry elf, laughing and jabbering incoherently. During the night he had developed a bit of fever and was slightly delirious.

Eventually he forsook the beach for the coconut groves. He made his way clear back to the hills which neither he nor Jolly Cauldron had ever attempted to explore. Hours passed, but to him they were insignificant. Like gravity, time also had lost its importance. Now in the hills other trees besides the palms commenced to appear, trees of luxurious foliage, trees of tropical splendor. Impulse drove him forward. He made no effort to overcome it. The only thing that mattered was that he was free, not held in check by anything.

Suddenly he paused. He had come to a waterfall, a delightful little cascade which dripped merrily over the rocks and ended in a pool of limpid water as cool as evening dew about twenty feet below where he was standing. But it was not the waterfall that made him pause, but a human laugh, the laugh of a girl as seductive and sweet as the nectar of poppies. Cautiously he leaned over the edge of the gray rocks and gazed down into the pool below, and there he saw a sight that repaid him in full for all the monotonous hours which he had passed on the island.

In the pool a young girl as gorgeous as any princess of the Arabian Nights sported merrily. She laughed and sang snatches of wild, weird love-songs. He knew that they were love-songs, even though he could not understand the words. She dived and swam as though she had been born in the water, as though she were a mermaid. The sunlight glistened on her golden-bronze body. She seemed to cast off an ethereal light, to out-rival the sun in splendor. Her young firm body was strong and slender. Her hair fell in wild confusion about her shoulders in an alluring blue-black maze of glory, a color which one seldom sees save in the most exotic paintings. Her intensely dark eyes seemed to glow with a suggestion of the hidden passion within her. Her teeth were pearls set in a mouth so tantalizingly red, so utterly voluptuous, that even the charm of the Sirens could not have been more seductive.

Guy lay there gazing at her until finally she emerged from her bath and gracefully dressed in a single garment, a silken, cloud-like thing that served to make the glory of her more pronounced. Then she disappeared among the trees.

For a long time he lay staring after her as though he expected her to return. As the moments passed and she did not come, he reluctantly rose to his feet and set off on his lonely journey back to camp. Now the fever had abated. His feet seemed made of lead. He was very tired.

When he reached their huts, he found Jolly Cauldron in an exceptionally bad humor.

"If you're going to stray off like this," he growled, "without permission, I'll have to tie you up again. I thought you were trained."

"I've had a singular adventure," said Guy, "but I refuse to tell you of it until you adopt a more civil tone."

"Amusing," jeered Jolly Cauldron, "a worthless mongrel aping a thoroughbred. However I'll change my manner. Are you hungry? I've made a fine kettle of stew for you. You see I love you as though you were my son. I try to gratify your every wish. There is also a pot of coffee boiling over the fire. Do I not deserve a little consideration for such thoughtfulness?"

After Guy had eaten and rested somewhat, he began to narrate his adventures. But in the middle of his story Jolly Cauldron interrupted him.

"Why do you tell me your dreams?" he asked sarcastically. "Last night I dreamed I was a moonbeam sitting on a cloud. It was a unique experience, but I'm not going to bore you by repeating it. You're getting to be too credulous. You are taking hallucinations seriously."

"Laugh if you wish," snapped Guy, "but I swear that I saw a lovely maiden bathing in a natural pool of water, a maiden of such peerless beauty that even you would bow down and worship before her."

"At least you are growing interesting," drawled Jolly Cauldron. "I like enthusiasm. But you are rather exaggerating when you suggest that I would bow down before any woman. I wouldn't. Do you know why? Because you can't trust any of them."

"Nevertheless the presence of that girl proves beyond a doubt that we are not far from civilization. If she is here, there must be others. There must be houses. If we can find where she dwells we may be able to get away from this island."

"I'm not hankering to get back to civilization," said Jolly Cauldron. "This is a bit of paradise. I can see no reason for leaving. We are leading a peaceful calm existence except when you go frisking off in the hills chasing phantoms. The air is restful. Life is sweet. I have been used to the hardships of the sea for years; now solitude rather appeals to me. Tell me, dog, have you ever seen such sunrises and sunsets? If you go back, what are you going back to? Can you find a beach more alluring than this, or water that laves the body more agreeably? I'm disgusted with you. All this beauty and still not satisfied."

Guy made no reply. He sat gazing moodily into the fire. At last he could restrain himself no longer.

"If it suits you," he said,"it suits me, but it is rather a pity that you could not see the gorgeous girl of the pool. As she stood on the brink about to dive, her yellow-bronze body shone in the sun as though she were a statue. Her expression was languorous. Her eyebrows were thin as though drawn by a single stroke of a kohl pencil. Her long silken lashes were canopies to eyes that no man could withstand. They seemed to have some hidden mystery lurking in their depths. Her forehead was as smooth as polished ivory. Her mouth was as red as a crushed cherry. But beautiful as was her face, the glory of her body rivaled it in magnificence. Here was a girl for whom all the kingdoms of the world might totter. Her bosom was firm and graceful. Were I an Arab I might compare her breasts to twin oranges. Her waist was very small, yet not slender enough to spoil the perfect contour of her figure. Her hands were tapering and rather fragile, the most expressive hands man ever gazed upon."

Guy paused for a moment; then he said tensely, "What would you give to behold such a girl, a girl possessed of all the animal passions of a wild thing of the forest, a girl who blends with sunsets and soft warm music; who looks like a goddess dancing by the black pool?"

Guy laughed loud and gratingly as he spoke. His voice carried a note of sarcasm that was maddening. With an oath Jolly Cauldron sprang to his feet. He seized Guy by the throat. His great fingers closed so tightly that Guy could not breathe.

"You'll find that girl for me," he cried hoarsely. "You'll take me to her or else I'll drown you in the cool water that has given you so much enjoyment."

At the last word he flung Guy from him. He stood raging like a wild bull. His hands clutched convulsively at the air as though they were still hungry for something to strangle.

Guy lay where he had fallen, fighting to get back his breath. He writhed in agony. His face was blue. His ears seemed like percussion caps that were in danger of exploding. His heart tore at his chest as though it were a spirit in prison struggling to get free. He was thoroughly beaten, yet Jolly Cauldron had not struck him once, merely squeezed his throat, throwing his world into chaos. The minutes dragged like years. Finally he ceased to struggle. Life wasn't worth fighting for. At best it was a hopeless battle. He closed his eyes. Death stared him in the face and he was glad. He welcomed oblivion so that he might for ever get away from Jolly Cauldron. And so he lay passive on the beach, and as ever when man ceases to cope with conditions, nature takes up the battle for him. Gradually the tumult in his ears subsided. His mind cleared. His heart ceased to clamor for release. His breathing became less painful. With closed eyes he cared not what passed over him.

Jolly Cauldron took a flask of whisky from his pocket.

"Here, dog," he said in a conciliatory voice; "drink this, it will revive you. We're going on a long journey tomorrow. We're going to explore the hills of dream in quest of the golden girl."

5

Jolly Cauldron was a creature of impulse. He no sooner thought of a thing than he attempted it. His personality had not been spoiled by youthful inhibitions and suppressions. He seldom made elaborate plans in advance. It was his custom to work out details as he went along. When he had kidnapped Guy in Stanbury Downs with the help of an old woman whose penury had hardened her conscience, and a half-ruined house that was tenantless, the affair had been the result of a momentary impulse. He had seen Gloria and Guy at a shop in London and had followed them at a discreet distance until he found out the address of the house where they were stopping in Stanbury Downs. This had been quite simple, for they had ordered several books to be mailed to them by a garrulous bookseller. From him Jolly Cauldron had drawn the information he desired.

At sunrise the next morning Jolly Cauldron again gave way to an impulse. Accompanied by Guy he set out in quest of a girl whom he had decided he desired, despite the fact that he had never even gazed upon her face. With him desire was akin to love. He pushed forward at a terrific pace as though he were incapable of fatigue.

Guy smiled to himself as he reflected that this was not incongruous, for most of the time he was like a thing of steel. To him it meant nothing to be tired. Guy had never seen him when he seemed in need of rest. True, in the evenings he had lain on the beach smoking, but it was not as though he did it through physical weariness. Rather he seemed to rest merely for the pleasure of enjoying the fantastic dreams which his inhalations evoked.

Toward noon the breeze died down entirely and the air grew as hot as if the sand beneath their feet were a furnace floor. The sun seemed suspended in the sky, a chandelier of scorching, searing fire. Guy walked along in a daze. The heat waves rose from the ground visibly. Guy wished to stop and rest, but Jolly Cauldron snarled at him.

"We'll not stop," he cried hoarsely, "not till we reach the black pool. Then you can drink till your liver floats away. What would be the sense of stopping here? You couldn't find water."

Guy closed his eyes to keep out the glaring light and plodded aimlessly along. He followed Jolly Cauldron like a whipped dog. When he felt as though he could endure the torture no longer, they came upon a spring. He babbled foolishly as he beheld it. Without pausing to drink of the water, he plunged right in, head and all. Even the pores of his skin drank. They absorbed the water like sponges.

As they continued their march, the heat seemed to relent. A gentle breeze sprang up. Peace returned to them. After that first spring they passed many others. Now that they were no longer thirsty, water was ever within reach of their hands. Eventually they arrived at the black pool in which Guy had beheld the lovely maiden bathing. Jolly Cauldron was impressed and pleased.

"You've proved that much of your story at least," he said. "Now can you remember which direction the girl went after leaving the pool?"

"She disappeared up the little winding path that runs directly under the falls," replied Guy. "Every detail is graven on my memory as though cut there with a chisel. I could not forget her if I wished. It is like a splendid scar that always will remain. Thus was the effect of the golden girl upon me."

Jolly Cauldron was not pleased at Guy's enthusiasm. He sniffed contemptuously but he did not voice his displeasure as he made his way to the tiny path Guy had indicated. He strode along as grim and glum as the most joyless of the old Stoic philosophers.

They had not continued far before they came to a clearing, a palm grove of surprizing loveliness. In the center of the grove stood a one-storied house, roughly built with a palm-thatched roof. It was of immense size and there were several outhouses standing near by almost equally as large. On the veranda of the house sat a man as repugnant as Jolly Cauldron. At their approach he looked up lazily. He had evidently been basking in the sun like a big beetle. He laughed shortly as they approached.

"Are you apparitions?" he drawled. "Or do you possess warm blood? At first glance you might be taken for monsters. At second glance you wouldn't be taken at all, not for anything."

He laughed gratingly at his own feeble effort at humor.

It was thus that Jolly Cauldron and Guy Sellers first met Fernay Corday, whose chief distinction in life was that he was the father of Kum-Kum, the golden girl.

Fernay Corday was a veritable gargoyle of a man, a monstrous gargoyle, and yet his ponderous size, far from being a mark of strength, gave the impression of extreme weakness. It suggested an enormous over-inflated balloon filled with noxious gases, likely to collapse at any moment, or a body washed up by the sea. His face was mottled, as blotchy as a piebald cow. There was no underglow of health shining through the skin. His eyes were dull, his nose bulbous and purple. His lower lip sagged as though the muscles had slipped and it was falling away from the decayed stumps of teeth.

Once a prosperous trader, he had succumbed to the witchery of languorous South Sea days. Now he dealt solely in copra, and from that alone he was able to reap far more than sufficient for his immediate requirements. He owned several coral islands outright and had contracts for the entire copra output of several others. Had he cared to exert himself he might have been one of the wealthiest men of the islands, for he was a keen trader and the natives liked him because he had almost become one of them.

Years before, he had married a Marquesan princess whose blood was half French and half Marquesan. Of this union Kum-Kum was born, Kum-Kum the little golden pagan, famed from Apia to Papeete. Fernay Corday himself was of mongrel extraction. He was descended from a long line of restless wanderers who had sailed the seven seas and intermarried so often that traces of any one particular race were obliterated. Therefore it was natural for him to be a rover. It was in the blood. Natural also was it for him to drift to Polynesia.

On land he had ever been a spendthrift, a waster, who squandered every cent he could earn. At sea he was forced to save, forced to accumulate a bit of money even against his will. However, he chafed under the constant restraint of a sailor's life. It held him down too utterly to one particular thing.

When on a certain voyage he landed in Tahiti, he decided at once that he had found at last the land in which he would settle. At the time he had had quite a bit of money as wealth is measured in the South Seas; so he bought an interest in a sailing-vessel which plied in and out among the islands. In this venture he prospered. He made more money than he could squander. At first he dealt in all commodities. Later he switched to copra alone. He never tried to branch out, to develop a larger business. He was satisfied with what he already had. An indolent life appealed to him.

In the end he abandoned the sea and settled on the island where Guy and Jolly Cauldron had found him. Now he had attained his heart's desire. His days were passed slothfully in a hammock on the screened porch of his one-storied house. His nights were passed in wild carousing, drunken nights and mysticism.

He lived with Kum-Kum and a score of Marquesan servants, not to mention two Chinese cooks who were veritable conjurers at their calling, for they could cook the most savory dishes from the most ordinary ingredients. They knew how to make the native kava, coconut brandy. It was this accomplishment that endeared them to Fernay Corday.

Fetia, Kum-Kum's mother, was dead. She had died of old age at thirty-eight. Like Kum-Kum she had been beautiful in her youth, but her blooming was forced like that of a hot-house flower. She lived intensely, loving pleasure, sleeping by day, feasting by night, a gorgeous flame consuming itself in its own glowing. Even when death was upon her she was not sorry for the manner in which her time had been passed.

"At least," she said, "I have lived, and that is much. Now I die. It is inevitable. There is nothing sad about it. One need only grieve over the death of a person who dies before he has lived."

So passed Fetia, mother of Kum-Kum.

Fernay Corday graciously welcomed Guy and Jolly Cauldron into his home. "I have enough rooms," he said, "to accommodate a regiment. But they are never used. This island is rather off the beaten track. Therefore it gives me great pleasure to welcome you. Enter my home and remain as long as you desire."

It was not until late in the evening that Kum-Kum appeared. Then when the dark shadows of night had settled down over the island and the dim oil lamps were lighted, she came softly to them, as though she had stepped out of the shadows through opaque curtains. Fernay Corday had ordered his Marquesan boys to play. There were three of them and they sat on the coral sand not far from the veranda steps, playing sad dreamy music. Then came Kum-Kum.

She whirled into the dim-lit circle, her strong white teeth glowing through her opened lips, as though lighted by the flame within her. In her hair were entwined a few hibiscus blossoms and about her neck was a string of pink coral beads. She was dressed in a single garment which accentuated the soft lines of her body.

The effect of her appearance upon the three men was peculiar. Fernay Corday gazed at her through half-closed eyes. He was amused. She was a pretty picture to gaze upon as he sipped his kava. Perhaps he thought of Fetia in the heyday of her youth. He was on the verge of sleep.

Crouched in the sand like a great ape was Jolly Cauldron. He had left his place on the veranda as soon as she had come to them. Even in his wildest fancies he had never imagined that she would be quite as lovely as this. His eyes were as bright as the eyes of one who has not learned to reason. He sat there immobile. His breath came audibly from his lips as though some great internal commotion were going on within him. His temples throbbed, the muscles of his mouth grew set as he gazed upon that gorgeous little pagan.

Guy had followed Jolly Cauldron. He, too, crouched in the sand, but the emotion within him differed from that which swept Jolly Cauldron. To Guy it seemed as though he were living the supreme artistic moment of his life. The dancing of Kum-Kum was like rhythmic poetry. Each wave of her hand was a quatrain, the lithesome swaying of her body a roundelay and the gentle rise and fall of her golden breasts were lyrics of enticement. After all, poetry need not be rendered in words. It is simply a mood, a series of harmonies, cadences, or a blending of soft-toned colors.

Even the peculiar attributes of the night served to act as a wild, weird frame to that brilliant picture. Above the palms, the sky was as black as the earth before day was created. The air was lifeless-still. Not a leaf stirred, not a flower trembled. All nature had paused to watch the charming spell of Kum-Kum, who danced with the abandon of one who lived each moment to the full. Her body swayed and undulated. When she gazed at Jolly Cauldron she smiled as though she were making sport of him. She seemed to lead him on for the sheer pleasure of ultimately repulsing him. But still he did not move; still he crouched ape-like in the sand.

Then came the storm. The thunder ripped the heavens in two and the rain poured down in sheets of chilling coldness. A sharp wind rose from nowhere and played havoc with the veranda lights. In a few moments the full fury of the storm struck and the lights went out. Reluctantly he rose to his feet and entered the house. He went at once to the room assigned to him. He wanted to be alone. He did not wish to talk.

The storm increased in violence. Its ferocity appalled him. He walked over to the open window. The rain crashed in in shrieking floods, but he did not care. Its coolness was like balm upon his forehead. It soothed his nerves. His fears vanished. Once more he was in tune with the witchery of the night. The air was charged with poetry, with charm, with haunting fragrant melodies.

Night and the down by the sea,

And the veil of the rain on the down:

And she came through the mist and the rain to me

From the safe, warm lights of the town.

The verses of Symons' poem kept running through the current of his thoughts. Even as they did so there came a blinding flash of lightning and by its illumination he beheld Kum-Kum, a thing of golden glory, dancing in the rain. She had thrown aside her single garment and now she danced with more utter abandon than ever. She might have been a pagan fire-worshipper dancing a religious epic to the storm.

Entranced, Guy waited for the next flash of lightning. When it came, so vivid it was, it seemed as if day had prematurely broken. Kum-Kum's dripping golden body glowed as though it were new-cast metal, still burning hot. But now she had paused in her dancing, for Jolly Cauldron stood over her. He had seized her in his arms and his lips were pressed to hers. Then the lightning died. The curtains of night swept down again.

Guy uttered an oath. For a moment only he hesitated, then he sprang through the window.

Blindly he plunged toward the spot where he had beheld Kum-Kum dancing. The last vestige of civilization had slipped from him. He was consumed with hatred. The night was so thick he felt as though he could grasp its texture in his hands and rend it like tapestry. The rain drove down in a pitiless deluge. The wind howled mockingly, and the trees moaned in their distress. Again the lightning flashed. He gazed quickly about. The palm-grove was deserted. Only the fury of the storm remained.

6

Morning dawned at last, calm and beautiful. The storms, the passions of the night were past. Jolly Cauldron at breakfast was as serene as a June day. Never had he been in a more amiable mood. His good-humor was infectious and Fernay Corday responded to it. But Guy did not. He sat gazing moodily at his plate, as gloomy as a London fog.

Kum-Kum that morning was rather wistful and demure. Now the fire in her eyes was dimmed. She flamed brightest after sunset. Guy was surprized and not a little annoyed to learn that Kum-Kum knew not a word of English. She spoke French entirely, of which he was totally ignorant.

Jolly Cauldron leaned across the table and tapped him on the shoulder.

"I know seven languages," he grinned, "foremost of which is French. Now am I repaid a hundredfold for the barren years of study."

Those days were days of jealousy and insane passion. Guy and Jolly Cauldron watched each other furtively. Jolly Cauldron was untterly enamored of Kum-Kum. He was insane about her. He who had always scoffed at religion now openly worshipped that pagan girl. The Beast was in love with Beauty. Guy elected himself a guardian, a protector to watch over Kum-Kum to see that no harm came to her from her semi-mad wooer. He, too, was fascinated by her. Many times he cursed that he knew no French and could not understand a word she uttered. Often he asked Jolly Cauldron what she had said, but only to be answered by glib lies.

"She says she's very fond of dogs but she doesn't care for them unless they are of noble pedigree. So I told her you had a violent temper, to beware of you because you were descended from all the dogs of war."

At times Guy walked alone down to the beach. He wanted to think calmly. Neither he nor Jolly Cauldron was making the slightest effort to leave the island, despite the fact that the next island was less than five miles away, where they could obtain passage to Papeete on one of the small trading-ships that continually plied in and out through the archipelago. He threw himself on the beach and gazed out to sea. Escape seemed distant. Jolly Cauldron would not leave the island and Guy was unwilling to desert Kum-Kum. He was not in love with her; he simply wished to watch over her. At that moment the island seemed the most beautiful spot in the world.

When Guy thought of Gloria his conscience bothered him. He was virtually deserting her, for he was no longer forced to remain on the island. And yet were he to leave, harm might befall Kum-Kum. He was torn between two duties, and as usual he chose the easiest, the one nearest at hand. In his decision he found no peace. It made him more reckless than ever.

One morning Jolly Cauldron made a daring proposition to Fernay Corday, taking the precaution to see that the trader was half drunk before doing so.

"Bestow the hand of Kum-Kum on me in marriage," he said bluntly, "and I will make you a present of ten gallons of the finest Scotch whisky."

Guy was speechless at the bold suggestion. He expected Fernay Corday to rise in his wrath and slay his loathsome guest on the spot, but the effect of the words was far different from his anticipation. Fernay Corday straightened up in his chair "and blinked his eyes several times, as though by so doing he could sober somewhat. Finally he spoke.

"Did you say gallons or quarts?" he asked.

"I said gallons," responded Jolly Cauldron. "You see there is nothing close about me. When I purchase jewels I am quite agreeable to offer a fortune in exchange."

Fernay Corday hesitated for a moment only, then he said craftily, "Make it twelve gallons."

Jolly Cauldron laughed shortly. "Twelve it is, then," he agreed.

In this simple fashion was the sale of Kum-Kum consummated. Jolly Cauldron intended to marry her legally, it is true, but nevertheless the affair was one of the most despicable barter. To pass judgment on the action of Fernay Corday one would have to be intimately acquainted with South Sea standards. There the art of love is looked upon as being as natural as a Gauguin painting. Gauguin himself was rather promiscuous in his wooings. The average Marquesan is an ephemeral lover. His amours are seldom lasting. When a couple have married and later parted it is looked upon philosophically. There is little weeping. Sorrows seldom last throughout a day. Morality is measured by an extremely flexible standard.

Although Fernay Corday was guilty of a questionable act in selling Kum-Kum, there is one thing to be said in his favor. He had a genuine liking for Jolly Cauldron. He considered him an excellent mate for Kum-Kum. According to his views, as a lover Jolly Cauldron left nothing to be desired. He was pleased with the outcome of their meeting. When he thought of the twelve gallons of good Scotch he was doubly pleased.

That night Guy went to his room immediately after dinner. He wished to be alone. His mind was a surging, restless flood. The thought of Jolly Cauldron possessing Kum-Kum nauseated him. All the primitive passions of earth were gripping his soul. If only Kum-Kum had understood English he could have discussed the matter with her. One thing was certain. She must escape from such slavery, even though it was called marriage.

He paced up and down the room as he always did when he was greatly distressed. He felt as though his brain were afire, as though his mind were consumed by the heat of his fury. In the end he decided that he would steal Kum-Kum. Jolly Cauldron had purchased Kum-Kum from Fernay Corday. Now he would steal her from Jolly Cauldron. He decided that he would make off with her in the dead of the night. They would leave the island in one of her father's canoes.

As a solution loomed up before him, his anger abated somewhat. He walked to the open window. The breeze struck warmly, drowsily against his face. A yellow-golden moon hung low in the sky like an enormous Chinese lantern. Its soft-toned radiance quite dwarfed the few lamps which hung from spikes driven into the palms. Soft music, haunting, wistful, sad, floated upon the air.

Fernay Corday reclined at full length in a hammock. His hands hung listlessly over the sides as though he were stupefied with kava. He was a great misshapen shadow rendering discordant the sweet notes of the music. As usual Jolly Cauldron crouched ape-like in the sand, as immobile as a carved Buddha. And Kum-Kum danced. Her slim loveliness wove a spell over Guy Sellers. Even at that distance he was fascinated. The moon seemed to glow more brightly that it might bathe her gorgeous body in its soft yellow light. Yellow moon, yellow moon and lanterns glowing in the trees. Her body shimmered like gold, her teeth gleamed white, her eyes shone with the light of diamond fires. His head whirled.

As he gazed at Kum-Kum a hundred disjointed impressions swept through his thoughts. She reminded him of flowers waving in the sun, of sea-foam breaking on a coral beach, of stars and poetry and soft radiance, of Shahrazad and the gorgeous slaves she told about, of wild oranges laved by mountain-dew, of yellow sapphires and opals blazing in the desert glare—strange, wild, discordant tapestry of dreams.

In the hush of the night, long after the lantern-moon had set, he went to her. The air was still, yet there seemed to be a suggestion of music lingering in the silence, as though nature had been singing and had paused on a beautiful note until the last reverberating echo had faded.

Kum-Kum's room was in the far end of the house, and as Guy stealthily crept forward the distance seemed unending. There was an antique lantern burning in the center of the hall, and it emphasized the distant shadows. His heart was beating like a sledge-hammer and he was surprized that the noise of it did not awaken everyone. Finally he arrived at Kum-Kum's door. He hesitated before pushing it open. His courage failed him, but his misgivings were fleeting. The next moment he opened the door and silently entered the room. Even a cat could not have glided more softly.

Before the vision of Kum-Kum he stopped. She was lying asleep on a low bed near the open window. Her blue-black hair fell about her shoulders untrammeled by comb or hair-pins. Her lips were smiling as though her dreams were pleasant. Over her slender form a coverlet was drawn, a coverlet of sheerest fabric. Beside her burned a copper bowl of fragrant incense. It cast off an eery blue glow. As the light fell on her pungent yellow skin, it made a green goddess of her.

Softly Guy placed his arms about her. The coverlet slipped away, revealing her lovely body dressed in a garment of tapa cloth as soft as rose-petals. As her warm body touched his, he trembled. From her hair an elusive perfume floated. At that moment everything on earth was forgotten. Only Kum-Kum mattered, Kum-Kum the pagan, the exotic, the daring, vivid, glowing girl of gold.

Back through the halls he went. He felt no fear. He was not nervous. He cared naught for Fernay Corday, nor even for the wrath of Jolly Cauldron. The strength of her attraction had made him as strong as Jason.

Kum-Kum did not awaken. He carried her as tenderly as though she had been a fragile orchid, an orchid of priceless worth. All the beauty of the Arabian Nights seemed dimmed by the glory of her. He longed to kiss her, to feel her soft warm lips against his. But he refrained because he was afraid, afraid of what might happen afterward. To kiss those lush red lips would have been as dangerous as plunging into the Maelstrom. Even the thought of her kisses made his head swim. And Jolly Cauldron had bought her. The thought made him shudder. And he pressed the lovely Kum-Kum a little closer to him. As he emerged from the house into the open air, a soft flower-sweetened breeze cooled his burning brow.

It was very dark in the coconut grove. The moon had set and the lamps that had hung to the tree-spikes had been removed. Overhead the stars glowed and glimmered in startling brilliance. The sky was so intensely clear it seemed as though it were a great inverted bowl. As he strode forward with his precious burden, he could scarcely see a yard before him. The fronds of the coconut palms far above stood out clearly in silhouette against an azure sky. Far in the distance the hill-tops loomed up grimly, half concealed in shadows. He walked slowly and cautiously by, but even so he collided with tree-trunks in the frond-shaded grove. The sea was not far away, where the outrigger canoes lay hidden, but he decided not to attempt to reach it in the darkness. He wished to keep Kum-Kum from danger. To continue onward would have been extremely perilous.

Very carefully he deposited her lovely form upon the sand. Although she sighed softly, she did not awaken. A thousand strange fancies flitted through his mind as he sat beside her. He thought of Gloria in New York, thousands of miles away. He wondered if she had kept her promise and divorced him. The reflection did not make him happy. Then he glanced toward Kum-Kum. In spite of himself he smiled. He was a bit like a modern Bluebeard. He already had one wife and now he was stealing a pagan girl. Where he was fleeing, he had not stopped to consider. He was bound for Hikuera. Beyond that he had never given a thought. Could he leave Kum-Kum there, abandon her after setting her free? If he did, Jolly Cauldron would eventually locate her and carry her back to the island. If he took Kum-Kum with him, away from the South Seas, there would be numerous difficulties when he got back to so-called civilized countries. He would be traveling with a lovely maiden who was unchaperoned and who was not his wife, not to mention the fact that he could not understand a word that maiden uttered. If he went back to New York with Kum-Kum, what explanation could he give Gloria?

At dawn Kum-Kum awoke. She sat up and gazed about her. Surprize, even dismay, was written on her face. She could not understand how she happened to be lying hidden in the jungle growth. Guy could not explain, for he spoke no French.