Popular Science Monthly/Volume 48/April 1896/The Savage Origin of Tattooing

| THE SAVAGE ORIGIN OF TATTOOING. |

By Prof. CESARE LOMBROSO.

I HAVE been told that the fashion of tattooing the arm exists among women of prominence in London society. The taste for this style is not a good indication of the refinement and delicacy of the English ladies: first, it indicates an inferior sensitiveness, for one has to be obtuse to pain to submit to this wholly savage operation without any other object than the gratification of vanity; and it is contrary to progress, for all exaggerations of dress are atavistic. Simplicity in ornamentation and clothing and uniformity are an advance gained during these last centuries by the virile sex, by man, and constitute a superiority in him over woman, who has to spend for dress an enormous amount of time and money, without gaining any real advantage, even to her beauty. But it is not desirable that so inordinate an accession to ornamentation as tattooing would be should be adopted; for an observation I have made on more than 5,000 criminals has demonstrated to me that this custom is held in too great honor among them. Thus, while out of 2,739 soldiers I have found tattoo marks only among 1·2 per cent, always limited to the arms and the breast; among 5,348 criminals, 667 were tattooed, or ten per cent of the adults and 3·9 per cent of the minors, Baer recently observed tattooing among two per cent of German criminals and 9·5 per cent of soldiers (Der Verbrecher, 1893).

Characteristics of Criminal Tattooing: Vengeance.—The minute study of the various signs adopted by malefactors shows us not only that they sometimes have a strange frequency, but often also a special stamp. A criminal whom I studied had on his breast between two poniards the fierce threat Je jure de me venger (I swear to avenge myself). He was an old Piedmontese sailor, who had killed and stolen for vengeance. A recidivistic thief wore on his breast the inscription, Malheur a moi! quelle sera ma fin? (Woe to me! what will be my end?)—lugubrious words, reminding us of those which Filippe, strangler of public women, had traced on his right arm, long before his condemnation, Né sous une mauvaise étoile (Born under an evil star).

Malassen, a ferocious assassin, who became in New Caledonia an executioner of convicts (Meyer, Souvenirs d’un Déporté), was covered from his feet to his head with grotesque and frightful tattoo marks. On his breast he had drawn a red and black guillotine, with the words in red letters: J'ai mal commencé, je finirai mal. C’est la fin qui m’attend (I have begun evil, I shall end evil. That is the end that awaits me). His right arm, which had inflicted death upon so many human beings, bore the terrible device, very appropriate to his hand, Mort à la chiourme (Death to the convict).

The famous Neapolitan camorrist Salsano had himself represented in an attitude of bravado. He held a stick in his hand, and was defying a police guard. Under the figure was his sobriquet, Éventre tout le monde (disembowel everybody); then came two hearts and keys connected with chains, in allusion to the secrecy of the camorrists.

We see, then, by these few examples, that there is a kind of hieroglyphic writing among criminals, that is not regulated or fixed, but is determined from daily events, and from argot, very much as would take place among primitive men. Very often, in fact, the key in the designs signifies the silence of secrecy, and the death's head vengeance. Sometimes the figures are replaced by points, as when a judicial arrest is marked on the arm with seventeen points, which means, according to the criminal, that he intends to Strike his enemy that number of times when he falls into his hands.

Another characteristic of criminals, which is also common to them with sailors and savages, is to trace the designs not only on the arms and the breast (the most frequent usage), but on nearly all the parts of the body. I have remarked one hundred tatooed on the arms, breast, and abdomen, five on the hands, three on the fingers, and three on the thigh.

A certain T, thirty-four years of age, who had passed many years in prison, had not, except on his cheeks and loins, a surface the size of a crown that was not tattooed. On his forehead could be read Martyr de la Liberté (Martyr of Liberty); the words being surmounted by a snake eleven centimetres long. On his nose he had a cross, which he had tried to efface with acetic acid.

A Venetian thief, who had served in the Austrian army, had on his right arm a double-headed eagle, and near it the names of his mother and his mistress Louise, with the strange epigraph for a thief: Louise, chère amante, mon unique consolation (Louise, dear loved one, my only consolation). Another thief wore on his right arm a bird holding a heart, stars, and an anchor. On the left arm of a prisoner Lacassagne found the words, Quand la neige tombera noire, B sortira de ma mémoire (When the snow falls black, B will pass out of my memory).

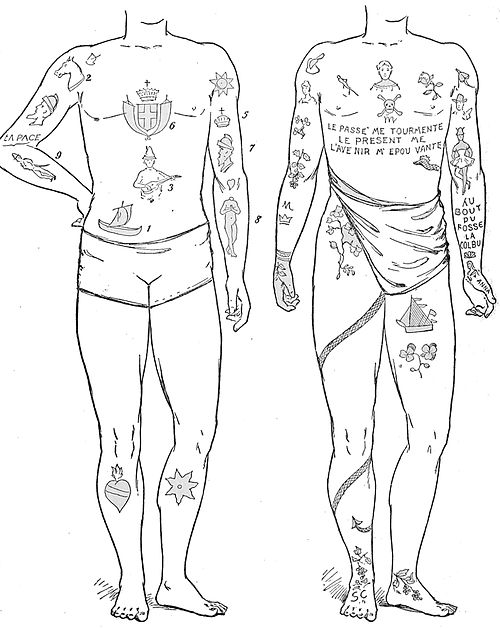

The multiplicity of marks results from the strange liking these curious heroes have of spreading on their body, just after

| |

| Fig. 1. | Fig. 2. |

the fashion of the American Indians, the adventures of their lives. For example, M C, twenty-seven years old (Fig. 1), who had been condemned at least fifty times for rebellion and assaults on men and horses, who had traveled, or rather wandered, a vagabond, in Spain and Africa with women whom he left suddenly, wore his whole history written on his skin. One design referred to the ship L'Espérance (No. 1), which was wrecked on the coast of Ireland, and on which he had gone as a sailor. A horse's head (No. 2) represented an animal which he had killed with a knife, from simple caprice, when twelve years old. A helmet (No. 7) indicated a policeman he had tried to kill. A headless woman with a heart on her neck indicated his mistress, who was frivolous (No. 8). The portrait of a brigand referred to a robber chief whom he took for his model (No. 9). A lute (No. 3) recalled a friend, a skillful player of the guitar, with whom he traveled over half of Europe. The star, the evil influence under which he was born (No. 4). The royal crown, "a political souvenir," he said, but rather, we say, his new trade of a spy—that is, the destruction of the kingdom (No. 5).

A French deserter who desired to avenge himself against his chief drew a poniard on his breast (Fig. 2, No. 1), to signify vengeance, and also a serpent. He further drew the ship on which he wished to escape, the epaulets which had been taken away from him, a dancing girl who had been his mistress, and then the sad inscriptions which were truly appropriate to his unhappy life.

Dr. Spoto sent me a study of the tattooing of a criminal who had been under his care. He wore all his sad adventures painted on his arm (see Archivio di Psichiatria, June, 1889). He had one hundred and five signs on his body, ten of which represented mistresses, nine hearts, eight flowers or leaves, five animals, twenty-eight names, surnames, or descriptions, and thirty-one poniards or warriors (Fig. 3). On his arm he had a figure of a lady winged and crowned; winged, he said, "because I made her take flight" (he had run away with her); crowned, because she had substituted for the crown of virginity the royal crown in becoming his mistress. She held in her hand a heart and an arrow, signifying her parents, to whom her flight had caused great grief. Beneath her were two branches, which signified that she kept herself always fresh. Two other of his loves explained their sad adventures by holding crumpled roses in their hands. In his hand he had an eagle, representing the ship on which he sailed, and beneath it a heart with three points, referring to the sufferings of Christ, whose birthplace he had visited at Bethlehem. A heart on his arm represented a mistress with whom he lived several years. It was pierced with an arrow, because he had abandoned the woman with two little children, who were represented by two bleeding hearts. Two hearts pierced with swords, on his forearm, represented two mistresses who would not yield to his desires except when threatened with death. They were connected by a chain with an anchor hanging from it, which signified that the women belonged to a sailor family, and a Greek cross above them

Fig. 3.

indicated that they were Greek. On his breast was a dancing girl carrying a bird, because she bounded like a bird. On his sides were a cock and a lion, the cock corresponding to women who wished to be paid: "When the cock sings, Spiritelli will pay." The lion meant that lie felt as strong as a lion. A smaller lion a few centimetres from this meant that even as among lions the stronger gains the victory over the weaker, so he, the stronger, had overcome those who would play the camorrist with him.

Never, I believe, have we had a more striking proof that tattooing contains real ideographic hieroglyphs which take the place of writing. They might be compared to the inscriptions of the ancient Mexicans and Indians, which, like the tattooings we have described, are the more animated history of individuals. Certainly these tattooings declare more than any official brief to reveal to us the fierce and obscene hearts of these unfortunates.

This multiplicity of figures proves also that criminals, like savages, are very little sensitive to pain. Another fact that characterizes tattooing is precocity. According to Tardieu and Berson, tattooing is never remarked in France before the age of sixteen years (excepting, of course, the cases of ship-boys who have borrowed the custom from sailors); yet we have found, even among the general public, four cases in children of from seven to nine years of age; and of eighty-nine adult criminals, sixty-six displayed tattooings which were made between nine and sixteen years.

Some tattoo marks are used by societies as signals of recognition. In Bavaria and the south of Germany the highway robbers, who are united into a real association, recognize one another by the epigraphic tattoo marks T. und L., meaning Thal und Land (valley and country), words which they exchange with one another, each uttering half the phrase, when they meet. Without that they would betray themselves to the police.[1]

What is the origin of this usage? Religion, which has so much power over peoples and which proves so obstinate in preserving ancient customs, has certainly contributed to maintain it among the more barbarous part of our populations; we see a quasi-official proof of it at Lorette. Those who cultivate a devotion for a saint believe that by engraving his image on their flesh they will give him a proof, a clear testimony, of their love. We know that the Phœnicians marked the sign of their divinity on their foreheads (Ewald, Judäischen Alterthum, iii); in the Marshall Islands they have to ask the permission of the gods to tattoo themselves; and the priests alone in New Zealand perform the office of tattooing (Scherzer). Lubbock adds to this that a woman who does not wear a tattoo mark can not enjoy eternal felicity. The women of Britain tattooed themselves in obedience to religion (Pliny, 33).

The second cause is the spirit of imitation. A Lombard soldier answered me laughingly one day when I rallied him on his having spent a small sum to spoil his arm: "See, monsieur, we are like sheep; and when one of us does anything we all imitate him at once, even if we risk doing ourselves harm."

Love of distinction also has its influence. A thief of the most incorrigible sort, who had six brothers tattooed like himself, implored me, although he was half covered with the oddest tattoo marks, to find him a professional tattooer to complete what might well be styled the embroidery of his skin. "When the tattooing is very curious and spread all over the body," he told me, "it is to us other thieves like the black coat of society with decorations; the more we are tattooed, the more we esteem one another; the more a person is tattooed, the more influence he has over his companions. On the contrary, one who is not tattooed has no influence; he is regarded simply as a good fellow, and is not esteemed by the company."

There are also tattooings inspired by vengeance. Bastrenga, the cruel assassin of T, had various tattoo marks on his arm (a horse, an anchor, etc.). On the advice of his father, who remonstrated with him that they would make him more easily recognizable, he effaced them. But in 1868 he was arrested anew by the police agents, and when he resisted actively one of them struck him so violently on the head that his eye was permanently hurt. Then, forgetting all prudence, he tattooed himself anew on the right arm; engraved there the fatal date of 1868, and a helmet on the arm that was to strike. "I shall keep this mark many years,", he said, "till the time comes when I can satisfy my vengeance." This fact is curious, and illustrates one of the causes that induce savages to tattoo themselves—for registration. It shows, too, that with the born criminals the spirit of revenge prevails over the most ordinary prudence, even when they have been put on their guard. Indolence also counts for something. It explains the number of cases of tattooing which we meet among deserters, prisoners, shepherds, and sailors. Among eighty-nine tattooed persons, I saw seventy-one who had been tattooed in prison. Inaction is even harder to endure than pain. The influence of vanity is still greater. Those even who have not studied the insane know how powerful this passion is, which is found in all grades of the social scale, and perhaps even in animals, and can lead to the strangest and most foolish actions, from the chevalier who dotes on a little bit of ribbon to the idiot who struts with a straw behind his ear. For this, savages who go entirely naked wear figures on their breasts; for this, our contemporaries who are clothed tattoo that part of the body which is most exposed to sight, especially the forearm, and more frequently the right than the left. An old soldier told me that in 1820 there was not a man in the army especially not a subordinate officer who had not been tattooed to exhibit his courage in supporting pain. The figures of the tattooing vary in New Zealand as do the fashion styles with us.

The spirit of the organization and the spirit of sect contribute to it. I have been led to this conclusion by the examination of some initials which I studied upon incendiaries at Milan, and of certain signs found on young police prisoners at Turin and Naples. Figures of tarantulas and of frogs appear often. I suspect that some groups of camorrists have adopted this new kind of primitive ornamentation to distinguish their sect, as they formerly adopted rings, pins, chains, and different cuts of the beard.

Lastly, the stimulus of the noblest human passions has had, its part. It is very natural that the rites of the village, the image of his patron, the recollections of infancy and of the heart's friend should return to the mind of the poor soldier, and be rendered more lively by the tattooed design, when he is struggling against danger, suffering, and privations.

But the primary, chief cause that has spread this custom among us is in my opinion atavism, or that other kind of historical atavism that is called tradition. Tattooing is, in fact, one of the essential characteristics of primitive man, and of men who still live in the savage state.

Some of those pointed bones which are used by modern savages in tattooing themselves have been found in the prehistoric grottoes of Avignac, and in the tombs of ancient Egypt. The Assyrians, according to Lucian, and the Dacians, according to Pliny, covered their whole bodies with figures. The Phœnicians and the Jews traced lines which they called "signs of God" on their foreheads and their hands (Ewald, Judäischen Alterthum, ii, p. 7). This usage was so widespread among the Britons that their name (from Brith, painting), like that of Pict and Pictons, seems to have been derived from it. See Cæsar. "These peoples," he says, "trace, with iron, designs on the skin of the youngest children, and color their warriors with Isatis tinctoria (woad) to render them more terrible on the field of battle."

I do not believe there is a single savage people that does not tattoo more or less. The Payaguns painted their faces in blue on feast days, in triangles and arabesques. The various negro tribes distinguished themselves from one another, especially the tribes of Bambaras, by horizontal or vertical lines traced on the face, the chest, and arms. Kafir warriors have the privilege of decorating their legs with a long azure line, which they are able to make indelible.

In Tahiti the women tattoo only the feet and hands or the ear, tracing collars or bracelets; the men, the whole body, on the hairy skin, on the nose, and the gums; and they often produce inflammations and gangrene, especially on the fingers and the gums. On the Marquesas Islands tattooing is a custom as well as a sacrament. Beginning at the age of fifteen or sixteen years, they put a girdle upon the young people and tattoo their fingers and legs, but always in a sacred place. Women, even princesses, have no right to tattoo anything but their hands and feet; grand personages cover their whole body; and while the designs on the lower part are delicate, those on the face lend it a grotesque and horrible aspect, so that enemies may be struck with fear. At Nukahiva, noble ladies are permitted to wear more numerous tattoo marks than the women of the people.

In Samoa, widows, it seems, tattoo the tongue; men paint the body from the girdle to the knees. The bald heads of old men in the Marquesas Islands may be seen covered with tattoo marks.

The fashionable ladies of Bagdad stained their temples and lips with azure, drew circles and rays of the same color on their legs, painted a blue girdle round their waists, and surrounded each of their breasts with a crown of blue flowers.

Tattooing is practiced in Polynesia at the age of from eleven to thirteen years; and is to these natives what the toga pretexta was to young Romans. In the Marquesas Islands it serves as a kind of clothing to the men; they might be mistakenly supposed to be covered with armor. Their face is hidden under the marks. The women here are generally but little tattooed, but coquettes wear the marks on their feet, hands, arms, legs, and forearms—designs so delicate that they might be taken for stockings and gloves in the daytime.

In order to please the women and to be able to find a wife, writes Délisle, the Laotian should be tattooed from the navel to below the calf, all round the thigh; while among the Dyacks the women submit to the operation in order to get husbands. Laotian tattooing is very animated, and represents fantastic animals, like those on the Buddhist monuments. Among the aborigines of the Marquesas Islands the tattooing exhibits, on the women, designs of every sort: boots, gloves, bows, suns, and lines drawn with remarkable fineness and perfection; on the men, animals—sharks, crabs, lizards, snakes—or plants, or geometrical figures. Here tattooing constitutes real works of art.

Sometimes tattooing and mutilation are combined, as in the famous chiefs' heads of New Zealand, which are overloaded with curved lines, with deep incisions showing as hollows, and with dark colors, with the intervals colored with dotted tattooing that gives the skin a bluish tinge. These curved lines spare no part of the face, and are closer and more numerous, according to the fame of the bearer of them as a warrior, or the antiquity of the origin of his chiefly dignity. The tattooing of the New Zealanders has found an unanticipated use in their relations with Europeans. Thus, the missionaries having bought a tract of land, the facial tattoo patterns of the vendor were drawn at the bottom of the deed, to serve as his signature.

The skins of all the grand chiefs of Guinea are in effect damascened. In New Zealand tattooing forms a sort of coat of arms. The common people are not allowed to practice it; and the chiefs are not permitted to decorate themselves with certain marks till they have accomplished some great enterprise. Toupes, an intelligent New Zealander, who was brought to London a few years ago, insisted upon a photographer taking pains to bring out his tattoo marks well. "Europeans," he said, "write their names with a pen; Toupes writes his this way. No matter," he said also to Dumont d'Urville, "if the Chonqui are more powerful than I, they can not wear the lines on their foreheads, for my family is more illustrious than theirs." The ancient Thracians and the Picts distinguished their chiefs by their special tattooing. The Pagas of Sumatra add a new color every time they have killed an enemy.

Tattooing is the true writing of savages, their first registry of civil condition. Some tattoo marks indicate the obligation of the debtor to serve his creditor for a certain time. The number and nature of objects received are likewise indicated (Krausen,Ueber die Tatouiren, 1873).

Nothing is more natural than to see a usage so widespread among savages and prehistoric peoples reappear in classes which, as the deep-sea bottoms retain the same temperature, have preserved the customs and superstitions, even to the hymns, of the primitive peoples, and who have, like them, violent passions, a blunted sensibility, a puerile vanity, long-standing habits of inaction, and very often nudity. There, indeed, among savages, are he principal models of this curious custom.

A last proof of our position is given by the hieroglyphics which we have found to be so frequent among the tattoo marks of criminals, and upon certain inscriptions which undoubtedly go back to an ancient age. A very interesting specimen of this kind is found in a study of tattooing in Portugal by Dr. Peixotto (Tatouage en Portugal, 1893), which I reproduce here:

| Sator | S | A | T | O | R |

| Arepo | A | R | E | P | O |

| Tenet | T | E | N | E | T |

| Opera | O | P | E | R | A |

| Rotas | R | O | T | A | S |

As the reader will see, it is the formula of a square, which reproduces the same words, "Sator," "Arepo," "Tenet," "Opera," and "Rotas," on whichever of the four sides we read it, and in whichever vertical or horizontal direction—one of those magical formulas which, according to Kohler (Anthropological Society of Berlin, 1891), were used to drive away fevers from the age of the Romans, as far back probably, at least, as Cato's time.

The influences of atavism and tradition seem to me to be confirmed by the fact that we find the custom of tattooing diffused among classes so tenacious of old traditions as shepherds and peasants.

After this study, it appears to me to be proved that this custom is a completely savage one, which is found only rarely among some persons who have fallen from our honest classes, and which does not prevail extensively except among criminals, with whom it has had a truly strange, almost professional, diffusion; and, as they sometimes say, it performs the service among them of uniforms among our soldiers. To us they serve a psychological purpose, in enabling us to discern the obscurer sides of the criminal's soul, his remarkable vanity, his thirst for vengeance, and his atavistic character, even in his writing.

Hence, when the attempt is made to introduce it into the respectable world, we feel a genuine disgust, if not for those who practice it, for those who suggest it, and who must have something atavistic and savage in their hearts. It is very much, in its way, like returning to the trials by God of the middle ages, to juridical duels atavistic returns which we can not contemplate without horror.

O Fashion! You are very frivolous; you have caused many complaints against the most beautiful half of the human race! But you have not come to this, and I believe you will not be permitted to come to it.

- ↑ Lacassagne has given us a large number of inscriptions tattooed on French criminals, which all contain criminal or obscene allusions. For example, we read: Eight times: "Son of misfortune."Nine times: "No chance."Three times: "Friends of the contrary."Four times: "Death to unfaithful women." Five times: "Vengeance." Twice: "Son of disgrace." Twice: "Born under an evil star." Three times: "Child of joy." Three times: "The past deceives me." Once: "The m. . . is worth more than all France." Once: "Vive la France and fried potatoes! Death to brutes." Once: "The present torments me; the future frightens me."