The year's at the spring

THE YEAR'S AT THE SPRING

AN ANTHOLOGY OF RECENT POETRY

COMPILED BY L. D'O. WALTERS AND

ILLUSTRATED BY HARRY CLARKE

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY HAROLD MONRO

BRENTANO'S

FIFTH AVENUE & 27TH STREET NEW YORK

First published September 1920

Printed in Great Britain

By Turnbull & Spears, Edinburgh

INTRODUCTION

I

THE best poetry is always about the earth itself and all the strange and lovely things that compose and inhabit it. When a 'great poet' sets himself the task of some 'big theme,' he needs only to hold, as it were, a magnifying glass to the earth. We who are born and live here like very much to imagine other worlds, and we have even mentally constructed such another in which to exist after dying on this one; but we were careful to make it a glorified version of our own earth, with everything we most love here intensified and improved to the utmost stretch of human imagination.

To each man his 'best poetry' is that which he is able most to enjoy. The first object of poetry is to give pleasure. Pleasure is various, but it cannot exist where the emotions or the imagination have not been powerfully stirred. Whether it be called sensual or intellectual, pleasure cannot be willed. It is impossible to feel happy because one wants to feel happy, or sad because one wishes to feel sad. But such bodily or mental conditions may be induced from outside through a natural agency such as poetry, or music.

Now those dreary people who would maintain that poetry should deal (some say exclusively) with what they call 'big themes,' or 'the larger life,' are merely advocating more use of the magnifying glass as against intensive cultivation of the natural eye. The poet is essentially he who examines carefully, and learns to know fully, every detail of common life. He seeks to name in a variety of manners, and to define, the objects about him, to compare them with other objects, near or remote, and to find, for the mere sake of enjoyment, wonderful varieties of description and comparison. When he imagines better places than his earth, or invents gods, the impersonation and combination of the fortunate qualities in man, he is then using the magnifying glass with talent, occasionally with rare genius. But the poet who seeks, without genius, to magnify is simply a fool who sees everything too big, and boasts, in the loudest voice he can raise, of his diseased eyesight.

One of the peculiarities, or perhaps rather the essential quality, of the lyrical poetry of to-day is a minute concentration on the objects immediately near it and an anxious carefulness to describe these in the most appropriate and satisfactory terms. Thus it is often accused of a neglect to sublimate the emotions, and many critics have been at pains to suggest that this affection for the nearest and that careful description of natural events denotes a smallness of mental range. Be it noted, however, that the eye which does not look too far often sees most. It is remarkable that English lyrical poetry should have learnt in this period of religious uncertainty to clasp itself at least to a reality that cannot be questioned or doubted. So far its faith reaches. It expresses a trustfulness in what it can definitely perceive, it hardly ventures outside the circles of human daily experience, and in this capacity it reveals an excellence of many kinds, sincerity often, and, at worst, a playfulness which, if ephemeral, is amusing at any rate to those whom it is intended to amuse, and appropriately irritating to those whom it wants to annoy.

But the most noticeable characteristic of the verse of our present moment is its dislike of the aloofness generally associated with English poetry. About twice a century language consolidates: phrases which were once soft and new harden with use; words once of a ringing beauty become dry and hollow through excessive repetition. This state of language is not much noticed by people who have no special use for it beyond the expression of daily needs. Moreover, they make new colloquial words for themselves as required without forethought or difficulty. Poets, however, must consciously search for new words, and a tired condition of their language is to them a great difficulty. The Victorians were absolute spendthrifts of words: no vocabulary could keep pace with their recklessness; they bequeathed a language almost ruined for sentimental purposes—words and phrases had acquired either such an aloofness that for a long time no one any more would trouble to reach up to them, or had become so thin and common that to use them would have been something like hack-sawing a piece of cotton.

Now in the anthology which follows we may notice a characteristic escape from these difficulties. Words have been brought down from their high places and compelled into ordinary use. This has been accomplished not so much through any new familiarity with the words themselves as by a certain naturalness in the attitude of the people employing them. Rupert Brooke's "Great Lover" is an example.

In short, these are the chief reasons why present-day poetry is readable and entertaining—that it deals with familiar subjects in a familiar manner; that, in doing so, it uses ordinary words literally and as often as possible; that it is not aloof or pretentious; that it refuses to be bullied by tradition: its style, in fact, is itself.

II

If an excuse is to be sought for the addition of this one more to the large number of existent collections of recent poetry, let it be in the nature of an explanation rather than an apology. Good, or even representative, poetry requires, in fact, no apology, but where the poems of some thirty-two different authors have been extracted from their books and placed side by side in one collection, a discussion of the apparent aims of the anthologist may be interesting, and will perhaps lead to a fuller enjoyment of the collection thus produced.

Some readers approach a volume of poems to criticize it, others with the object of gaining pleasure. To give pleasure is assuredly the object of this volume. Moreover, it is adapted to the tastes of almost any age, from ten to ninety, and may be read aloud by grandchild to grandparent as suitably as by grandparent to grandchild. It is an anthology of Poems, not of Names. For instance, though Thomas Hardy is on the list, the lyric chosen to represent him is actually more characteristic of the book itself than of the mind of that great and aged poet. It is, in fact, Christian in atmosphere. It is not a typical specimen of Mr Hardy's style. It shows him in that occasional rather sad mood of regret for a lost superstition. It is not the best of Hardy, but rather a poem admirably suited to the book, which also happens, as by chance, to be by the author of "The Dynasts" and "Satires of Circumstance."

III

The collection as a whole is modern, and all except eight of its authors are living and writing. Of those eight, five died as soldiers in the European War, and are represented mainly by what is known as 'War poetry.' Otherwise such poetry is fortunately absent. This absence may be justified by the fact that most of the verse written on the subject of the War turns out, surveyed in cooler blood, to be, as any sound judge of literature must always have known, definitely and unmistakably bad. Much of it is by now, or should be, repudiated by its authors. It was too often "the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings"; it too seldom originated from "emotion recollected in tranquillity."

Rupert Brooke's sonnets "The Dead" and "The Soldier" were popular almost from their first publication. They belong undoubtedly to the best traditions of English poetry. Julian Grenfell's "Into Battle," and, in a lesser degree, the "Home Thoughts from Laventie" of Edward Wyndham Tennant, have acquired popularity among a larger number of folk than can be included in the general term 'literary circles.' Neither of the composers of these verses was a professional poet. Both were men of attractive personality and strong feeling, with education, taste, and an occasional impulse to write gracefully. Intrinsically either poem might as easily have been inspired by an Indian frontier raid as by a European war. They do not affect the traditions of English poetry by subject or by form. It will be found, as the years pass, that always fewer 'War poems' can still be read with pleasure, the incidents which gave rise to them having become dim in human memory. And these will not be read because of their association with the Great War, but for their qualities as poems and their power to stir enjoyment or sunrise in the reader.

Consider those four melancholy lines by which Edward Thomas is here represented, remarkable for their concentration and for the crowd of images they can suggest. At present the words "where all that passed are dead" alone associate this poem with the War. But death comes through so many causes that twenty years from now a footnote would be needed if it were desired to emphasize that association.

J. E. Flecker's "Dying Patriot," one of his three poems in this book, was written in 1914 in Switzerland, where he was dying of consumption. It is certainly less a 'War poem' than the same author's "War Song of the Saracens."

The verses entitled "A Petition," by R. E. Vernède, are of a different kind. They are written in conventional Henley-Kiplingese, and contain too many incidents of a type of poetic expression that has been used to excess, as "wider than all seas," "to front the world," "quenchless hope," "All that a man might ask thou hast given me, England." They are, nevertheless, useful in the collection as a set-off against the other 'War poems' and an instance of the more ephemeral type of patriotic verse.

Thus it would appear that the anthologist has displayed wisdom when including in this volume only few pieces that may be associated with the War, and those few {with one exception} on the score of their literary merit, and for no other reason.

IV

Poets of to-day write individually less than their predecessors, and most of them are satisfied to publish only a proportion of what they write. None of the eight referred to above left us any great bulk of verse. Four at least, however, are becoming daily better known to the reading public, and of these Rupert Brooke and J. E. Flecker have already their dozens of conscious or unconscious imitators. The form, rhythm, or Eastern atmosphere of Flecker's poetry, the cynicism and wit of Brooke's, recur somewhat diluted in the verse of almost every young undergraduate. Neither Lionel Johnson nor Mary Coleridge has ever become so well known or received so much attention from the average plagiarist, while the reputation of Edward Thomas has been of slow and uncertain growth. Johnson's poetry is too intellectual for the average reader. The wonderful, small lyrics of Mary Coleridge are esoteric rather than general. Nevertheless, this anthology includes, most advisedly, a good poem by Johnson, one indeed which has had a quiet, but strong, influence on modern lyrical poetry, namely, the lines to the statue of King Charles at Charing Cross, and also a charming impression by Mary Coleridge.

"Street Lanterns" is a good example of that poetry of close observation to which reference has already been made. It is a small, careful description of a London scene. It assumes that the reader has observed as much, and that he will enjoy to be reminded and brought back for a moment in imagination to autumn and street-mending. The advocate of 'big themes' will inevitably condemn such verse, for the poet has aimed at neither size nor grandeur, has indeed sought rather to diminish her subject than enlarge it.

V

This anthology, it has been remarked above, is one rather of particular poems than of well-known authors. Several names of repute are not to be found in the index. William Watson is only represented by "April," a little catch that might come to any man of feeling on a spring walk. To think in terms of these verses is at once not to mind having left an umbrella at home. Hilaire Belloc gives a sharp impression of early rising; he also sings in a great voice all the glories of his favourite part of England. W. H. Davies brings sheep across the Atlantic, and he talks to a kingfisher. Mrs Meynell contributes "The Shepherdess," that well-known description of a pure and serene mind, also two London poems, of which one is the lovely "November Blue." John Masefield is not to be read in his best style, but the three poems we find here are thoroughly English, full of the love of the island soil and of its sea, and are probably in the book for that reason. So much for some of the well-known contributors. Side by side with them we find the unknown name of H. H. Abbott, whose "Black and White" is a sketch of remarkable clarity and interest.

Death, so favourite a subject with poets, is seldom allowed to figure in this book. Betsey-Jane would insist on going to Heaven, but is told, in the charming verses by Helen Parry Eden, that it simply "would not do." The whole book is too full of pleasure and the experience of being alive: Betsey-Jane should read it. She might remember all her life the advice given on page 117, and be saved hundreds of pounds in lawyers' bills when she is grown up.

Let the reader turn to page 114. Here is the style in which good poetry prefers to teach, and by which it achieves more in eleven lines than a Martin Tupper in 11,000. Mr Pepler has written down only one sentence, charmingly improved by a series of most natural rhymes. It is a very nasty hit at the lawyer. He does not tell him he is not a 'gentleman,' or anything so strong as that. He pays him what might be taken for a compliment. He assumes that he does understand his own job. Then he enumerates the things he does not understand. He attaches no blame: he makes a statement only; one that the lawyer certainly will not think worth arguing about, but that his client may advisedly take to heart.

Ralph Hodgson's "Stupidity Street" argues in somewhat the same manner. It does not suggest that anyone should become vegetarian, or that it is wrong to kill birds. It names a street and gives a reason for doing so. It is an angry little poem, but impersonal.

"The Bells of Heaven," by the same author, simply chances a hint that something might happen if something else did. It is a suggestion only, but made by one who knows what he thinks, and how to think it. Into a few lines a whole philosophy is concentrated.

Thus Pepler or Ralph Hodgson nudge peoples arms and draw attention to traditional stupidities.

Walter De la Mare puts the children to sleep with "Nod," or bewitches them with the Mad Prince's Song; or he takes us to an Arabia which never existed, but is one of those countries more beautiful than any we know, and therefore we love to imagine it.

Look at that full moon on page 53, which Dick saw "one night." Here is the possible experience of man, woman, child, dog, fox, bear—or even nightingale—all concentrated into the shortest and plainest account of something that happened to Dick. He and Betsey-Jane, though quite different in kind, belong to the same world. Betsey-Jane is plainly more romantic than Dick.

But, talking of the moon, we may turn back to Mr Chesterton on page 36. Here we find something incongruous in the collection: a poem that wishes deliberately to strike a note. The donkey is a much better fellow than Mr Chesterton seems to think: he does not ask for glorification, nor would he utter that boast of the last two lines. Would a man not rather "go with the wild asses to Paradise" than have the case for the donkey pleaded before him in this obtrusive manner?

Turn back four pages and you will find:

For the good are always the merry,

Save by an evil chance,

And the merry love the fiddle,

And the merry love to dance.

This, by W. B. Yeats, represents a much pleasanter type of thought. In these verses of the Irish poet we have the gaiety of a man who, knowing all about religion, can afford not to be sentimental. And here is the spirit of the book.

The happiness of those who love the earth is so different from the pleasure by proxy of those that abide it in the idea of going to some Heaven afterward. Mr Yeats' "Fiddler of Dooney" is that type of fellow who accepts the symbolism of a national religion only in so far as it may help him to enjoy the condition of being alive. And in his "Lake Isle of Innisfree" he imagines a Paradise which is of the earth only. And he takes you there by reason of his own longing.

VI

This anthology, as a whole, is romantic; its language is simple; its philosophy is that of everyday life, and is entirely undisturbing. It contains a large proportion of poems by authors who write more particularly for children, such as P. R. Chalmers, Rose Fyleman, Queenie Scott-Hopper, and Marion St John Webb, or of children s poems by authors who do not actually specialize in that style, such as "The Ragwort," by Frances Cornford; "Cradle Song," by Sarojini Naidu; "Check," by James Stephens, and others. Two of its authors remain necessarily unmentioned here, namely, the compiler of the book and the writer of this Introduction.

Some people make it their business to pick anthologies to pieces, and they seem to enjoy themselves. "Why is this included?" they cry; "Why is that left out?"—a form of criticism nearly always beside the point. Inclusion or exclusion is in the taste and discretion of the anthologist.

This Introduction may, it is hoped, stimulate the reader of the poems which follow to think about them carefully in their relation to each other, and in their relation to English poetry as a whole. For though it has frequently been emphasized that the object of poetry (and particularly of lyrical poetry) is to give pleasure, it should nevertheless be added that intellectual pleasure cannot be gathered at random, or without certain preparation of the mind to receive it.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

For permission to use copyright poems the Editor is indebted to:

The Authors—H. H. Abbott, Hilaire Belloc, P. R. Chalmers, G. K. Chesterton, Frances Cornford, W. H. Davies, Walter De la Mare, John Drinkwater, Rose Fyleman, W. W. Gibson, Robert Graves, Ralph Hodgson, Teresa Hooley, Margaret Mackenzie, Irene R. McLeod, John Masefield, Alice Meynell, Harold Monro, Sarojini Naidu, H. D. C. Pepler, James Stephens, Sir William Watson, Marion St John Webb, and W. B. Yeats.

The Literary Executors of Rupert Brooke, Mary E. Coleridge (Sir Henry Newbolt), James Elroy Flecker (Mrs Flecker), Julian Grenfell (Lady Desborough), Lionel Johnson (Mr Elkin Mathews), Edward Wyndham Tennant (Lady Glenconner), Edward Thomas (Messrs Selwyn and Blount), R. E. Vernède.

And the following Publishers, in respect of the poems selected:

Messrs Burns and Oates, Ltd.

- Alice Meynell: Collected Poems.

Messrs Constable and Co., Ltd.

- Walter De la Mare: The Listeners, Peacock Pie.

Messrs J. M. Dent and Sons, Ltd.

- G. K. Chesterton: The Wild Knight.

Messrs Duckworth and Co.

- Hilaire Belloc: Verses.

Mr A. C. Fifield

- W. H. Davies: Collected Poems.

Messrs George G. Harrap and Co., Ltd.

- E. J. Brady: The House of the Winds.

- Queenie Scott-Hopper: Pull the Bobbin!

- Marion St John Webb: The Littlest One.

Mr W. Heinemann, London, and the John Lane Company, New York

- Sarojini Naidu: The Golden Threshold.

Messrs Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston

- John Drinkwater: Poems by John Drinkwater.

Mr John Lane, London, and the John Lane Company, New York

- Helen Parry Eden: Bread and Circuses.

- Edward Wyndham Tennant, by Pamela Glenconner.

Messrs Macmillan and Co., Ltd., London, and the Macmillan Company, New York

- W. W. Gibson: Whin.

- Ralph Hodgson: Poems.

- J. Stephens: The Adventures of Seumas Beg, Songs from the Clay.

- W. B. Yeats: Poems: Second Series.

The Macmillan Company, New York

- John Masefield: Ballads and Poems.

Messrs Maunsel and Co.

- P. R. Chalmers: Green Days and Blue Days.

Messrs Methuen and Co., Ltd.

- Rose Fyleman: Fairies and Chimneys, The Fairy Green.

The Poetry Bookshop

- H. H. Abbott: Black and White.

- Frances Cornford: Spring Morning.

- R. Graves: Over the Brazier.

Messrs Sands and Co.

- M. Mackenzie: The Station Platform, and Other Poems.

Mr Martin Secker

- J. E. Flecker: Collected Poems.

- Francis Brett Young: Poems, 1916-1918.

Messrs Selwyn and Blount, London, and Messrs Henry Holt and Company, New York

- Edward Thomas: Poems.

Messrs Sidgwick and Jackson, Ltd.

- J . Redwood Anderson: Walls and Hedges.

- John Drinkwater: Swords and Ploughshares.

Messrs Sidgwick and Jackson, Ltd., and the John Lane Company, New York

- Rupert Brooke: 1914, and Other Poems.

Messrs T. Fisher Unwin, Ltd.

- W. B. Yeats: Poems.

CONTENTS

ARRANGED UNDER NAMES OF AUTHORS

| Abbott, H. H. | |

| Black and White | 126 |

| Anderson, J. Redwood | |

| The Bridge | 118 |

| Belloc, Hilaire | |

| The Early Morning | 37 |

| The South Country | 38 |

| Brady, E. J. | |

| A Ballad of the Captains | 47 |

| Brooke, Rupert | |

| The Dead | 60 |

| The Great Lover | 61 |

| The Soldier | 65 |

| Chalmers, P. R. | |

| If I had a Broomstick | 74 |

| Roundabouts and Swings | 75 |

| Chesterton, G. K. | |

| The Donkey | 36 |

| Coleridge, Mary E. | |

| Street Lanterns | 116 |

| Cornford, Frances | |

| In France | 71 |

| The Ragwort | 72 |

| Davies, W. H. | |

| The Kingfisher | 85 |

| Sheep | 86 |

| De la Mare, Walter | |

| Arabia | 51 |

| Full Moon | 53 |

| Nod | 54 |

| The Song of the Mad Prince | 56 |

| Drinkwater, John | |

| A Town Window | 78 |

| Eden, Helen Parry | |

| To Betsey-Jane, on her Desiring to go Incontinently to Heaven | 117 |

| Flecker, James E. | |

| Brumana | 79 |

| The Dying Patriot | 80 |

| November Eves | 82 |

| Fyleman, Rose | |

| Alms in Autumn | 105 |

| I Don't Like Beetles | 107 |

| Wishes | 108 |

| Gibson, W. W. | |

| Sweet as the Breath of the Whin | 113 |

| Graves, Robert | |

| Star-Talk | 83 |

| Grenfell, Julian | |

| Into Battle | 91 |

| Hardy, Thomas | |

| The Oxen | 128 |

| Hodgson, Ralph | |

| The Bells of Heaven | 99 |

| The Song of Honour | 100 |

| Stupidity Street | 102 |

| Hooley, Teresa | |

| Sea-Foam | 123 |

| Johnson, Lionel | |

| By the Statue of King Charles at Charing Cross | 66 |

| Mackenzie, Margaret | |

| To the Coming Spring | 103 |

| McLeod, Irene R. | |

| Lone Dog | 73 |

| Masefield, John | |

| Sea Fever | 41 |

| Tewkesbury Road | 43 |

| The West Wind | 45 |

| Meynell, Alice | |

| A Dead Harvest | 57 |

| November Blue | 58 |

| The Shepherdess | 59 |

| Monro, Harold | |

| Overheard on a Saltmarsh | 94 |

| A Flower is Looking through the Ground | 96 |

| Man Carrying Bale | 97 |

| Naidu, Sarojini | |

| Cradle-Song | 35 |

| Pepler, H. D. C. | |

| The Law the Lawyers Know About | 114 |

| Scott-Hopper, Queenie | |

| Very Nearly! | 109 |

| What the Thrush Says | 110 |

| Stephens, James | |

| Check | 69 |

| When the Leaves Fall | 70 |

| Tennant, E. W. | |

| Home Thoughts in Laventie | 88 |

| Thomas, E. | |

| The Cherry Trees | 98 |

| Vernède, R. E. | |

| A Petition | 124 |

| Walters, L. D'O. | |

| All is Spirit and Part of Me | 115 |

| Watson, Sir William | |

| April | 31 |

| Webb, Marion St John | |

| The Sunset Garden | 112 |

| Yeats, W. B. | |

| The Fiddler of Dooney | 32 |

| The Lake Isle of Innisfree | 34 |

| Young, Francis Brett | |

| February | 121 |

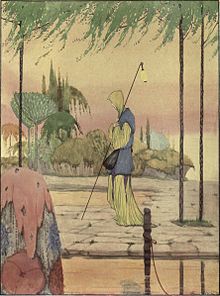

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

| The Lake Isle of Innisfree | Frontispiece |

| April | 31 |

| The Fiddler of Dooney | 32 |

| Cradle-Song | 35 |

| The Donkey | 36 |

| Sea Fever | 41 |

| A Ballad of the Captains | 47, 48 |

| Arabia | 51 |

| The Song of the Mad Prince | 56 |

| The Shepherdess | 59 |

| The Dead | 60 |

| The Great Lover | 62, 64 |

| If I had a Broomstick | 74 |

| The Dying Patriot | 80, 82 |

| Star-Talk | 84 |

| Overheard on a Saltmarsh | 94 |

| To the Coming Spring | 103 |

| Alms in Autumn | 106 |

| Very Nearly! | 109 |

| All is Spirit and Part of Me | 115 |

| Black and White | 126 |

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse