FURNITURE (from “furnish,” Fr. fournir), a general term

of obscure origin, used to describe the chattels and fittings required

to adapt houses and other buildings for use. Wood,

ivory, precious stones, bronze, silver and gold have been used

from the most ancient times in the construction or for the

decoration of furniture. The kinds of objects required for

furniture have varied according to the changes of manners and

customs, as well as with reference to the materials at the command

of the workman, in different climates and countries.

Of really ancient furniture there are very few surviving examples,

partly by reason of the perishable materials of which it was usually

constructed; and partly because, however great may have been

the splendour of Egypt, however consummate the taste of Greece,

however luxurious the life of Rome, the number of household

appliances was very limited. The chair, the couch, the table,

the bed, were virtually the entire furniture of early peoples,

whatever the degree of their civilization, and so they remained

until the close of what are known in European history as the

middle ages. During the long empire-strewn centuries which

intervened between the lapse of Egypt and the obliteration of

Babylon, the extinction of Greece and the dismemberment of

Rome and the great awakening of the Renaissance, household

comfort developed but little. The Ptolemies were as well lodged

as the Plantagenets, and peoples who spent their lives in the

open air, going to bed in the early hours of darkness, and rising

as soon as it was light, needed but little household furniture.

Indoor life and the growth of sedentary habits exercised a

powerful influence upon the development of furniture. From

being splendid, or at least massive, and exceedingly sparse and

costly, it gradually became light, plentiful and cheap. In the

ancient civilizations, as in the periods when our own was slowly

growing, household plenishings, save in the rudest and most

elementary forms, were the privilege of the great—no person

of mean degree could have obtained, or would have dared to

use if he could, what is now the commonest object in every

house, the chair (q.v.). Sparse examples of the furniture of

Egypt, Nineveh, Greece and Rome are to be found in museums;

but our chief sources of information are mural and sepulchral

paintings and sculptures. The Egyptians used wooden furniture

carved and gilded, covered with splendid textiles, and supported

upon the legs of wild animals; they employed chests and coffers

as receptacles for clothes, valuables and small objects generally.

Wild animals and beasts of the chase were carved upon the

furniture of Nineveh also; the lion, the bull and the ram were

especially characteristic. The Assyrians were magnificent in

their household appointments; their tables and couches were

inlaid with ivory and precious metals. Cedar and ebony were

much used by these great Eastern peoples, and it is probable that

they were familiar with rosewood, walnut and teak. Solomon’s

bed was of cedar of Lebanon. Greek furniture was essentially

Oriental in form; the more sumptuous varieties were of bronze,

damascened with gold and silver. The Romans employed Greek

artists and workmen and absorbed or adapted many of their

mobiliary fashions, especially in chairs and couches. The Roman

tables were of splendid marbles or rare woods. In the later

ages of the empire, in Rome and afterwards in Constantinople,

gold and silver were plentifully used in furniture; such indeed

was the abundance of these precious metals that even cooking

utensils and common domestic vessels were made of them.

The architectural features so prominent in much of the

medieval furniture begin in these Byzantine and late Roman

thrones and other seats. These features became paramount as

Pointed architecture became general in Europe, and scarcely

less so during the Renaissance. Most of the medieval furniture,

chests, seats, trays, &c., of Italian make were richly gilt and

painted. In northern Europe carved oak was more generally

used. State seats in feudal halls were benches with ends carved

in tracery, backs panelled or hung with cloths (called cloths of

estate), and canopies projecting above. Bedsteads were square

frames, the testers of panelled wood, resting on carved posts.

Chests of oak carved with panels of tracery, or of Italian cypress

(when they could be imported), were used to hold and to carry

clothes, tapestries, &c., to distant castles and manor houses;

for house furniture, owing to its scarcity and cost, had to be

moved from place to place. Copes and other ecclesiastical

vestments were kept in chests with ornamental lock plates and

iron hinges. The splendour of most feudal houses depended

on pictorial tapestries which could be packed and carried from

place to place. Wardrobes were rooms fitted for the reception

of dresses, as well as for spices and other valuable stores. Excellent

carving in relief was executed on caskets, which were of

wood or of ivory, with painting and gilding, and decorated with

delicate hinge and lock metal-work. The general subjects of

sculpture were taken from legends of the saints or from metrical

romances. Renaissance art made a great change in architecture,

and this change was exemplified in furniture. Cabinets (q.v.) and

panelling took the outlines of palaces and temples. In Florence,

Rome, Venice, Milan and other capitals of Italy, sumptuous

cabinets, tables, chairs, chests, &c., were made to the orders

of the native princes. Vasari (Lives of Painters) speaks of

scientific diagrams and mathematical problems illustrated in

costly materials, by the best artists of the day, on furniture made

for the Medici family. The great extent of the rule of Charles V.

helped to give a uniform training to artists from various countries

resorting to Italy, so that cabinets, &c., which were made in

vast numbers in Spain, Flanders and Germany, can hardly be

distinguished from those executed in Italy. Francis I. and

Henry VIII. encouraged the revived arts in their respective

dominions. Pietra dura, or inlay of hard pebbles, agate, lapis

lazuli, and other stones, ivory carved and inlaid, carved and gilt

wood, marquetry or veneering with thin woods, tortoiseshell,

brass, &c., were used in making sumptuous furniture during the

first period of the Renaissance. Subjects of carving or relief

were generally drawn from the theological and cardinal virtues,

from classical mythology, from the seasons, months, &c. Carved

altarpieces and woodwork in churches partook of the change in

style.

The great period of furniture in almost every country was,

however, unquestionably the 18th century. That century saw

many extravagances in this, as in other forms of art, but on the

whole it saw the richest floraison of taste, and the widest sense

of invention. This is the more remarkable since the furniture

of the 17th century has often been criticized as heavy and coarse.

The criticism is only partly justified. Throughout the first three-quarters

of the period between the accession of James I. and

that of Queen Anne, massiveness and solidity were the distinguishing

characteristics of all work. Towards the reign of

James II., however, there came in one of the most pleasing and

elegant styles ever known in England. Nearly a generation

before then Boulle was developing in France the splendid and

palatial method of inlay which, although he did not invent it,

is inseparably associated with his name. We owe it perhaps to

the fact that France, as the neighbour of Italy, was touched

more immediately by the Renaissance than England that the

reign of heaviness came earlier to an end in that country than on

the other side of the Channel. But there is a heaviness which is

pleasing as well as one which is forbidding, and much of the

furniture made in England any time after the middle of the

17th century was highly attractive. If English furniture of

the Stuart period be not sought after to the same extent as that

of a hundred years later, it is yet highly prized and exceedingly

decorative. Angularity it often still possessed, but generally

speaking its elegance of form and richness of upholstering lent

it an attraction which not long before had been entirely lacking.

Alike in France and in England, the most attractive achievements

of the cabinetmaker belong to the 18th century—English Queen

Anne and early Georgian work is universally charming; the

regency and the reigns of Louis XV. and XVI. formed a period

of the greatest artistic splendour. The inspiration of much of

the work of the great English school was derived from France,

although the gropings after the Chinese taste and the earlier

Gothic manner were mainly indigenous. The French styles of the

century, which began with excessive flamboyance, closed before

the Revolution with a chaste perfection of detail which is perhaps

more delightful than anything that has ever been done in

furniture. In the achievements of Riesener, David Röntgen,

Gouthière, Oeben and Rousseau de la Rottière we have the high-water

mark of craftsmanship. The marquetry of the period,

although not always beautiful in itself, was executed with

extraordinary smoothness and finish; the mounts of gilded

bronze, which were the leading characteristic of most of the work

of the century, were finished with a minute delicacy of touch

which was until then unknown, and has never been rivalled since.

If the periods of Francis I. and Henry II., of Louis XIV. and

the regency produced much that was sumptuous and even elegant,

that of Louis XVI., while men’s minds were as yet undisturbed

by violent political convulsions, stands out as, on the whole,

the one consummate era in the annals of furniture. Times of

great achievement are almost invariably followed directly by

those in which no tall thistles grow and in which every little

shrub is magnified to the dimensions of a forest tree; and the

so-called “empire style” which had begun even while the last

monarch of the ancien régime still reigned, lacked alike the graceful

conception and the superb execution of the preceding style.

Heavy and usually uninspired, it was nurtured in tragedy and

perished amid disaster. Yet it is a profoundly interesting style,

both by reason of the classical roots from which it sprang and

the attempt, which it finally reflected, to establish new ideas in

every department of life. Founded upon the wreck of a lingering

feudalism it reached back to Rome and Greece, and even to

Egypt. If it is rarely charming, it is often impressive by its

severity. Mahogany, satinwood and other rich timbers were

characteristic of the style of the end of the 18th century;

rosewood was most commonly employed for the choicer work

of the beginning of the 19th. Bronze mounts were in high

favour, although their artistic character varied materially.

Previously to the middle of the 18th century the only cabinet-maker

who gained sufficient personal distinction to have had

his name preserved was André Charles Boulle; beginning with

that period France and England produced many men whose

renown is hardly less than that of artists in other media. With

Chippendale there arose a marvellously brilliant school of English

cabinetmakers, in which the most outstanding names are those

of Sheraton, Heppelwhite, Shearer and the Adams. But if the

school was splendid it was lamentably short-lived, and the 19th

century produced no single name in the least worthy to be

placed beside these giants. Whether, in an age of machinery,

much room is left for fine individual execution may be doubted,

and the manufacture of furniture now, to a great extent, takes

place in large factories both in England and on the continent.

Owing to the necessary subdivision of labour in these

establishments, each piece of furniture passes through numerous

distinct workshops. The master and a few artificers formerly

superintended each piece of work, which, therefore, was never

far removed from the designer’s eye. Though accomplished

artists are retained by the manufacturers of London, Paris and

other capitals, there can no longer be the same relation between

the designer and his work. Many operations in these modern

factories are carried on by machinery. This, though an economy

of labour, entails loss of artistic effect. The chisel and the knife

are no longer in such cases guided and controlled by the sensitive

touch of the human hand.

|

|

|

|

Fig. 1.—Venetian Folding Chair of

carved and gilt walnut, leather

back and seat; about 1530. |

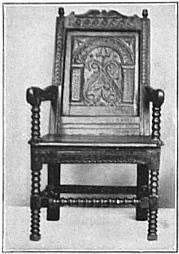

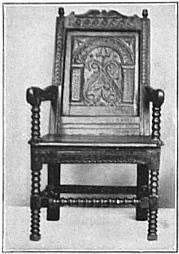

Fig. 2.—Oak Arm-chair. English,

17th century. |

Fig. 3.—Arm-chair, solid seat, cane

back; about 1660. |

Fig. 4.—Arm-chair, stuffed back and

seat; about 1650. | |

|

|

|

Fig. 5.—Painted and carved High-

Back Chair; about 1660. |

Fig. 6.—Carved Walnut Chairs. English, early 18th century.

The arm-chair is inlaid. |

Fig. 7.—Walnut Chair; about 1710. | |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 8.—Carved Mahogany Chair

in the style of Chippendale; 2nd

half of 18th century. |

Fig. 9.—Carved Mahogany Arm-chair,

in the style of Chippendale, with

ribbon pattern. |

Fig. 10.—Carved and Inlaid Mahogany

Chair, in the style of Hepplewhite;

late 18th century. |

Fig. 11.—Mahogany Chair in the

style of Sheraton; about 1780. | |

|

|

|

|

Fig. 12.—Painted and gilt Arm-chair

with cane seat, in the style of

Adam; about 1790. |

Fig. 13.—Arm-chair of carved and gilt

wood with stuffed back, seat and

arms. French, Louis XV. style. |

Fig. 14.—Mahogany Arm-chair. Empire

style, early 19th century, said to have

belonged to the Bonaparte family. |

Fig. 15.—Painted and gilt Beech Chair.

English, about 1800. | |

|

|

Fig. 1.—Front of Oak Coffer with wrought iron bands.

French, 2nd half of 13th century. |

Fig. 2.—English Oak Chest, dated 1637. | |

|

|

Fig. 3.—Italian (Florentine) Coffer of Wood with gilt arabesque

stucco ornament, about 1480. |

Fig. 4.—Italian “Cassone” or Marriage Coffer, 13th century.

Carved and gilt wood with painted front and ends. | |

|

|

| Fig. 5.—Walnut Table with expanding leaves. Swiss, 17th century. |

Fig. 6.—Oak Gate-Legged Table. English,

17th century. | |

|

|

Fig. 7.—Writing Table. French, end of Louis XV. period.

Riesener marquetry, ormolu mounts and Sèvres plaques. |

Fig. 8.—Painted Satin-Wood Tables, in the style of Sheraton,

about 1790. |

| (The above are in the Victoria and Albert Museum, except Fig. 8, which were in the Bethnal Green Exhibition, 1892.) | |

|

|

1. CARVED OAK SIDEBOARD. English,

17th century. Victoria and Albert Museum. |

2. CARVED OAK COURT CUPBOARD. English, early 17th

century. Victoria and Albert Museum. | |

|

|

| 3. EBONY CARVED CABINET. The interior decorated with inlaid ivory and coloured woods; French or Dutch, middle of 17th century. Victoria and Albert Museum. |

4. VENEERED CHEST OF DRAWERS. About 1690. Lent to Bethnal Green Exhibition by Sir Spencer Ponsonby-Fane, G.C.B. | |

|

|

5. EBONY ARMOIRE. With tortoise-shell panels inlaid with brass and other metals, and ormolu mountings. Designed by Bérain, and executed by André Boulle. French, Louis XIV. period.

Victoria and Albert Museum. |

6. GLASS-FRONTED BOOKCASE AND CABINET.

Of mahogany. In the style of Sheraton, about 1790. Lent to the Bethnal Green Exhibition by the late Vincent J. Robinson, C.I.E. | |

|

|

| 1. COMMODE OF PINE. With marquetry of brass, ebony, tortoise-shell,

mother-of-pearl, ivory, and green-stained bone. “Boulle” work with designs in the style of Bérain. French, late period of Louis XIV. |

2. COMMODE. With panels of Japanese lacquer and ormolu mountings, in the style of Caffieri. French, Louis XV. period. | |

|

|

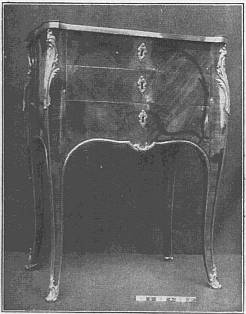

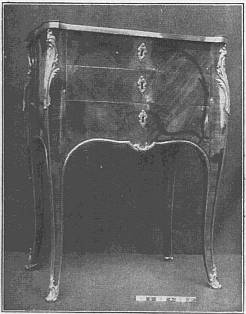

| 3. TABLE OF KING AND TULIP WOODS. With ormolu mountings. Louis XV. period. |

4. ESCRITOIRE À TOILETTE. Formerly belonging to Marie Antoinette. Of tulip and sycamore woods inlaid with other coloured woods, ormolu mounts. Louis XV. period. | |

|

|

| 5. FOUR-POST BEDSTEAD. Of oak inlaid with bog-oak and holly, from the “Inlaid Room” at Sizergh Castle, Westmorland. Latter half of sixteenth century. |

6. CARVED AND GILT BEDSTEAD. With blue silk damask coverings and hangings. French, late 18th century. Louis XVI. period. |

| From the Victoria and Albert Museum, S. Kensington. | |

|

|

| Photo, Mansell & Co. |

| THE “BUREAU DU ROI,” MADE FOR LOUIS XV., NOW IN THE LOUVRE. For description, see Desk. |

A decided, if not always intelligent, effort to devise a new

style in furniture began during the last few years of the 19th

century, which gained the name of “l’art nouveau.” Its pioneers

professed to be free from all old traditions and to seek inspiration

from nature alone. Happily nature is less forbidding than many

of these interpretations of it, and much of the “new art” is a

remarkable exemplification of the impossibility of altogether

ignoring traditional forms. The style was not long in degenerating into extreme extravagance. Perhaps the most striking consequence of this effort has been, especially in England, the

revival of the use of oak. Lightly polished, or waxed, the cheap foreign oaks often produce very agreeable results, especially when there is applied to them a simple inlay of boxwood and stained holly, or a modern form of pewter. The simplicity of these English forms is in remarkable contrast to the tortured and ungainly outlines of continental seekers after a conscious

and unpleasing “originality.”

Until a very recent period the most famous collections of historic furniture were to be found in such French museums as

the Louvre, Cluny and the Garde Meuble. Now, however, they

are rivalled, if not surpassed, by the magnificent collections of

the Victoria and Albert Museum at South Kensington, and the

Wallace collection at Hertford House, London. The latter, in

conjunction with the Jones bequest at South Kensington, forms

the finest of all gatherings of French furniture of the great

periods, notwithstanding that in the Bureau du Roi the Louvre

possesses the most magnificent individual example in existence.

In America there are a number of admirable collections representative

of the graceful and homely “colonial furniture”

made in England and the United States during the Queen Anne

and Georgian periods.

See also the separate articles in this work on particular forms of

furniture. The literature of the subject has become very extensive,

and it is needless to multiply here the references to books. Perrot

and Chipiez, in their great Histoire de l’art dans l’antiquité (1882

et seq.) deal with ancient times, and A. de Champeaux, in Le Meuble

(1885), with the middle ages and later period; English furniture is

admirably treated by Percy Macquoid in his History of English

Furniture (1905); and Lady Dilke’s French Furniture in the 18th

Century (1901), and Luke Vincent Lockwood’s Colonial Furniture in

America (1901), should also be consulted. (J. P.-B.)