1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Mitre

MITRE (Lat. mitra, from Gr. μίτρα, a band, head-band, head-dress), a liturgical head-dress of the Catholic Church, generally proper to bishops.

1. Latin Rite.—In the Western Church its actual form is that of a sort of folding cap consisting of two halves which, when not worn, lie flat upon each other. These sides are stiffened, and when the mitre is worn, they rise in front and behind like two horns pointed at the tips (cornua mitrae). From the lower rim of the mitre at the back hang two bands (infulae), terminating in fringes. In the Roman Catholic Church mitres are divided into three classes: (1) Mitra pretiosa, decorated with jewels, gold plates, &c.; (2) Mitra auriphrygiata, of white silk, sometimes embroidered with gold and silver thread or small pearls, or of cloth of gold plain; (3) Mitra simplex, of white silk damask, silk or linen, with the two falling bands behind terminating in red fringes. Mitres are the distinctive headdress of bishops; but the right to wear them, as in the case of the other episcopal insignia, is granted by the popes to other dignitaries—such as abbots or the heads and sometimes all the members of the chapters of cathedral or collegiate churches. In the case of these latter, however, the mitre is worn only in the church to which the privilege is attached and on certain high festivals. Bishops alone, including of course the pope and his cardinals, are entitled to wear the pretiosa and auriphrygiata; the others wear the mitra simplex.

The proper symbol of episcopacy is not so much the mitre as the ring and pastoral staff. It is only after the service of consecration and the mass are finished that the consecrating prelate asperses and blesses the mitre and places on the head of the newly consecrated bishop, according to the prayer which accompanies the act, “the helmet of protection and salvation,” the two horns of which represent “the horns of the Old and New Testaments,” a terror to “the enemies of truth,” and also the horns of “divine brightness and truth” which God set on the brow of Moses on Mount Sinai. There is no suggestion of the popular idea that the mitre symbolizes the “tongues of fire” that descended on the heads of the apostles at Pentecost.

According to the Roman Caeremoniale the bishop wears the mitra pretiosa on high festivals, and always during the singing of the Te Deum and the Gloria at mass. He is allowed, however, “on account of its weight,” to substitute for the pretiosa the auriphrygiata during part of the services, i.e. at Vespers from the first psalm to the Magnificat, at mass from the end of the Kyrie to the canon. The auriphrygiata is worn during Advent, and from Septuagesima to Maundy Thursday, except on the third Sunday in Advent (Gaudete), the fourth in Lent (Laetare) and on such greater festivals as fall within this time. It is worn, too, on the vigils of fasts, Ember Days and days of intercession, on the Feast of Holy Innocents (if on a week-day), at litanies, penitential processions, and at other than solemn benedictions and consecrations. At mass and Vespers the mitra simplex may be substituted for it in the same way as the auriphrygiata for the pretiosa. The simplex is worn on Good Friday, and at masses for the dead; also at the blessing of the candles at Candlemas, the singing of the absolution at the coffin, and the solemn investiture with the pallium. At provincial synods archbishops wear the pretiosa, bishops the auriphrygiata, and mitred abbots the simplex. At general councils bishops wear white linen mitres, cardinals mitres of white silk damask; this is also the case when bishops and cardinals in pontificalibus assist at a solemn pontifical function presided over by the pope.

Lastly, the mitre, though a liturgical vestment, differs from the others in that it is never worn when the bishop addresses the Almighty in prayer—e.g. during mass he takes it off when he turns to the altar, placing it on his head again when he turns to address the people (see 1 Cor. xi. 4).

The origin and antiquity of the episcopal mitre have been the subject of much debate. Some have claimed for it apostolical sanction and found its origin in the liturgical head-gear of the Jewish priesthood. Such proofs as have been adduced for this view are, however, based on the fallacy of reading into words (mitra, infula, &c.) Origin and Antiquity. used by early writers a special meaning which they only acquired later. Mitra, even as late as the 15th century, retained its simple meaning of cap (see Du Cange, Glossarium, s.v.); to Isidore of Seville it is specifically a woman’s cap. Infula, which in late ecclesiastical usage was to be confined to mitre (and its dependent bands) and chasuble, meant originally a piece of cloth, or the sacred fillets used in pagan worship, and later on came to be used of any ecclesiastical vestment, and there is no evidence for its specific application to the liturgical head-dress earlier than the 12th century. With the episcopal mitre the Jewish miznephet, translated “mitre” in the Authorized Version (Exod. xxviii. 4, 36), has nothing to do, and there is no evidence for the use of the former before the middle of the 10th century even in Rome, and elsewhere than in Rome it does not make its appearance until the 11th.[1]

The first trustworthy notice of the use of the mitre is under Pope Leo IX. (1049–1054). This pope invested Archbishop Eberhard of Trier, who had accompanied him to Rome, with the Roman mitra, telling him that he and his successors should wear it in ecclesiastico officio (i.e. as a liturgical ornament) according to Roman custom, in order to remind him that he is a disciple of the Roman see (Jaffé, Regesta pont. rom., ed. Leipzig, 1888, No. 4158). This proves that the use of the mitre had been for some time established at Rome; that it was specifically a Roman ornament; and that the right to wear it was only granted to ecclesiastics elsewhere as an exceptional honour.[2] On the other hand, the Roman ordines of the 8th and 9th centuries make no mention of the mitre; the evidence goes to prove that this liturgical head-dress was first adopted by the popes some time in the 10th century; and Father Braun shows convincingly that it was in its origin nothing else than the papal regnum or phrygium which, originally worn only at outdoor processions and the like, was introduced into the church, and thus developed into the liturgical mitre, while outside it preserved its original significance as the papal tiara (q.v.). From Leo IX.’s time papal grants of the mitre to eminent prelates became increasingly frequent, and by the 12th century it had been assumed by all bishops in the West, with or Without papal sanction, as their proper liturgical head-dress. From the 12th century, too, dates the custom of investing the bishop with the mitre at his consecration.

It was not till the 12th century that the mitre came to be regarded, as specifically episcopal, and meanwhile the custom had grown up of granting it honoris causa to other dignitaries besides bishops. The first known instance of a mitred abbot is Egelsinus of St Augustine’s, Canterbury, who received the honour from Pope Alexander II. in 1063. From Non-bishops. this time onward papal bulls bestowing mitres, together with other episcopal insignia, on abbots become increasingly frequent. The original motive of the recipients of these favours was doubtless the taste of the time for outward display; St Bernard, zealous for the monastic ideal, denounced abbots for wearing mitres and the like more pontificum, and Peter the Cantor roundly called the abbatial mitre “inane, superfluous and puerile” (Verb. abbrev. c. xliv. in Migne, Patrolog. lat. 205, 159). It came, however, to symbolize the exemption of the abbots from episcopal jurisdiction, their quasi-episcopal character, and their immediate dependence on the Holy See. No such significance could attach to the grant of the usus mitrae (under somewhat narrow restrictions as to where and when) to cathedral dignitaries. The first instance is again a bull of Leo IX. (1051) granting to Hugh, archbishop of Besançon, and his seven cardinals the right to wear the mitre at the altar as celebrant, deacon and subdeacon, a similar privilege being granted to Bishop Hartwig of Bamberg in the following year. The intention was to show honour to a great church by allowing it to follow the custom doubtless already established at Rome. Subsequently the privilege was often granted, sometimes to one or more of the chief dignitaries, sometimes to all the canons of a cathedral (e.g. Campostella, Prague).

Mitres were also sometimes bestowed by the popes on secular sovereigns, e.g. by Nicholas II. (1058–1061) on Spiteneus (Spytihnĕw) II., duke of Bohemia; by Alexander II. on Wratislaus of Bohemia; by Lucius II. (1144–1145) on Roger of Sicily; and by Innocent III., in 1204, on Peter of Aragon. In the coronation of the emperor, more particularly, the mitre played a part. According to the 14th Roman ordo, of 1241, the pope places on the emperor’s head first the mitra clericalis, then the imperial diadem. Father Braun (Liturgische Gewandung, p. 457) gives a picture of a seal of Charles IV. representing him as wearing both.

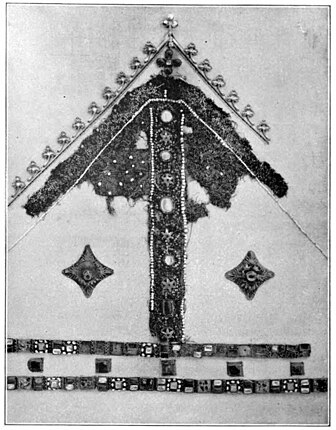

The original form of the mitre was that of the early papal tiara (regnum), i.e. a somewhat high conical cap. The stages of its general development from this shape to the high double-horned modern mitre are clearly traceable (see fig. 1), though it is impossible exactly to distinguish them in point of date. The most characteristic Development of Form. modifications may be said to have taken place from the 11th to the middle of the 13th century. About 1100 the conical mitre begins to give place to a round one; a band of embroidery is next set over the top from back to front, which tends to bulge up the soft material on either side; and these bulges develop into points or horns. Mitres with horns on either side seem to have been worn till about the end of the 12th century, and Father Braun gives examples of their appearances on episcopal seals in France until far into the 13th. Such a mitre appears on a seal of Archbishop Thomas Becket (Father Thurston, The Pallium, London, 1892, p. 17). The custom was, however, already growing up of setting the horns over the front and back of the head instead of the sides (the mitre said to have belonged to St Thomas Becket, now at Westminster Cathedral, is of this type),[3] and with this the essential character of the mitre, as it persisted through the middle ages, was established. The exaggeration of the height of the mitre, which began at the time of the Renaissance, reached its climax in the 17th century. This ugly and undignified type is still usually worn in the Roman Catholic Church, but in some cases the earlier type has survived, and many bishops are also now reverting to it.

| Drawn by Father J. Braun and reproduced from his Liturgische Gewandung by permission of B. Herder. |

| Fig. 1.—Evolution of the Mitre from the 11th century to the present day. |

The decoration of mitres was characterized by increasing elaboration as time went on. From the first the white conical cap seems to have been decorated round the lower edge by a band or orphrey (circulus). To this was added later a vertical orphrey (titulus), usually from the centre of the front of the circulus to that of the back, partly in order to hide the seam, partly to emphasize the horns when those were to left and right. When the horns came to be set before and behind, the vertical orphrey retained its position. Of the surviving early mitres the greater number have only the orphrey embroidered, the body of the mitre being left plain. Very early, however, the custom arose of ornamenting the triangular spaces between the orphreys with embroidery, usually a' round medallion, or a star, set in the middle, but sometimes figures of saints, &c. (e.g. the early example from the cathedral of Anagni, reproduced by Braun, p. 469). The richness and variety of decoration increased from the 14th century onwards. Architectural motives even were introduced, as frames to the embroidered figures of saints, while sometimes the upper edges of the mitre were ornamented with crockets, and the horns with architectural finials. Finally, the traditional circulus and titulus seem all but forgotten, the whole front and back surfaces of the mitre being ornamented with embroidered pictures or with arabesque patterns. The latter is characteristic of the mitre in the modern Roman Catholic Church, the tradition of the local Roman Church having always excluded the representation of figures on ecclesiastical vestments.

2. Reformed Churches.—In most of the reformed Churches the use of mitres was abandoned with that of the other vestments. They have continued to be worn, however, by the bishops of the Scandinavian Lutheran Churches. In the Church of England the use of the mitre was discontinued at the Reformation. There is some Church of England. evidence to show that it was used in consecrating bishops up to 1552, and also that its use was revived by the Laudian bishops in the 17th century (Hierurgia anglicana ii. 242, 243, 240). In general, however, there is no evidence to prove that this use was liturgical, though the silver-gilt mitre of Bishop Wren of Ely (d. 1667), which is preserved, is judged from the state of the lining to have been worn. The instances of the use of the mitre quoted in Hier. anglic. ii. 310, as carried by the bishop of Rochester at an investiture of the Knights of the Bath (1725), and by the archbishops and bishops at the coronation of George II. (1727), have no liturgical significance. The tradition of the mitre as an episcopal ornament has, nevertheless, been continuous in the Church of England, “and that on three lines: (1) heraldic usage; (2) its presence on the head of effigies of bishops, of which a number are extant, of the 16th, 17th, 18th and 19th centuries; (3) its presence in funeral processions, where an actual mitre or the figure of one was sometimes carried, and sometimes suspended over the tomb” (Report on the Ornaments of the Church, p. 106). The liturgical use of the mitre was revived in the Church of England in the latter part of the 19th century, and is now fairly widespread.

3. Oriental Rites.—Some form of liturgical head-dress is common to all the Oriental rites. In the Orthodox Eastern Church the mitre (Gr. μίτρα; Slav. mitra) is, as in the Western Church, proper only to bishops. Its form differs entirely from that of the Latin Church. In general it rather resembles a closed crown, consisting of a circlet from which rise two arches intersecting each other at right angles. Circlet and arches are richly chased and jewelled; they are filled out by a cap of stiff material, often red velvet, ornamented with pictures in embroidery or appliqué metal. Surmounting all, at the intersection of the arches is a cross. In Russia this usually lies flat, only certain metropolitans, and by prescription the bishops of the eparchy of Kiev, having the right to have the cross upright (see fig. 2). In the Armenian Church priests and archdeacons, as well as the bishops, wear a mitre. That of the bishops is of the Latin form, a custom dating from a grant of Pope Innocent III.; that of the priests, the sagvahart, is not unlike the Greek mitre (see fig. 3). In the Syrian Church only the patriarch wears a mitre, which resembles that of the Greeks. The biruna of the Chaldaean Nestorians, on the other hand, worn by all bishops, is a sort of hood ornamented with a cross. Coptic priests and bishops wear the ballin, a long strip of stuff ornamented with crosses &c., and wound turban-wise round the head; the patriarch of Alexandria has a helmet-like mitre, the origin of which is unknown, though it perhaps antedates the appearance of the phrygium at Rome. The Maronites, and the uniate Jacobites, Chaldaeans and Copts have adopted the Roman mitre.

The mitre was only introduced into the Greek rite in comparatively modern times. It was unknown in the earlier part of the 15th century, but had certainly been introduced by the beginning of the 16th. Father Braun suggests that its assumption by the Greek patriarch was connected with the changes due to the capture of Constantinople by the Turks. Possibly, as its form suggests, it is based on the imperial crown and symbolized at the outset the quasi-sovereignty over the rayah population which Mahommed II. was content to leave to the patriarch. In 1589 it was introduced into Russia, when the tsar Theodore erected the Russian patriarchate and bestowed on the new patriarch the right to wear the mitre, sakkos and mandyas, all borrowed from the Greek rite. A hundred years later the mitre, originally confined to the patriarch, was worn by all bishops.

See J. Braun, S.J., Die liturgische Gewandung (Freiburg-im-Breisgau, 1907), pp. 424–498. The question of the use of the mitre in the Anglican Church is dealt with in the Report of the Sub-Committee of the Convocation of Canterbury on the Ornaments of the Church and its Ministers (1908). See also the bibliography to the article Vestments. (W. A. P.)

- ↑ Father Braun, S. J., has dealt exhaustively with the supposed evidence for its earlier use—e.g. he proves conclusively that the mitra mentioned by Theodulph of Orleans (Paraenes. ad episc.) is the Jewish miznephet, and the well-known miniature of Gregory the Great (not St Dunstan, as commonly assumed) wearing a mitre (Cotton MSS. Claudius A. iii.) in the British Museum, often ascribed to the 10th or early 11th century, he judges from the form of the pallium and dalmatic to have been produced at the end of the 11th century “at earliest.” The papal bulls granting the use of mitres before the 11th century are all forgeries (Liturgische Gewandung, 431–448).

- ↑ That it had been already so granted is proved by a miniature containing the earliest extant representations of a mitre, in the Exultete rotula and baptismal rotula at Bari (reproduced in Berteaux, L’Art dans l’Italie méridionale, I., Paris, 1904).

- ↑ In Father Braun’s opinion, expressed to the writer, this mitre, which was formerly at Sens, belongs probably to the 13th century.