1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Pianoforte

PIANOFORTE (Ital. piano, soft, and forte, loud). The group of keyed stringed musical instruments, among which the pianoforte is latest in order of time, has been invented and step by step developed with the modern art of music, which is based upon the simultaneous employment of different musical sounds. In the 10th century the “organum” arose, an elementary system of accompaniment to the voice, consisting of fourths and octaves below the melody and moving with it; and the organ (q.v.), the earliest keyed instrument, was, in the first instance, the rude embodiment of this idea and convenient means for its expression. There was as yet no keyboard of balanced key levers; sliders were drawn out like modern draw-stops, to admit History of Evolution. the compressed air necessary to make the pipes sound. About the same time arose a large stringed instrument, the organistrum,[1] the parent of the now obsolete hurdy-gurdy; as the organ needed a blower as well as an organist, so the player of the organistrum required a handle-turner, by whose aid the three strings of the instrument were made to sound simultaneously upon a wheel, and, according to the well-known sculptured relief of St George de Boscherville, one string was manipulated by means of a row of stoppers or tangents pressed inwards to produce the notes. The other strings were drones, analogous to the drones of the bagpipes, but originally the three strings followed the changing organum.

In the 11th century, the epoch of Guido d’Arezzo, to whom the

beginning of musical notation is attributed, the Pythagorean

monochord, with its shifting bridge, was used in the singing

schools to teach the intervals of the plain-song of the church.

The practical necessity, not merely of demonstrating the proportionate

relations of the intervals, but also of initiating pupils

into the different gradations of the church tones, had soon after

Guido’s time brought into use quadruplex-fashioned monochords,

which were constructed with scales, analogous to the modern

practice with thermometers which are made to show both

Monochord; Clavichord.

Réaumur and Centigrade, so that four lines

indicated as many authentic and as many plagal

tones. This arrangement found great acceptance,

Fig. 1.—Earliest existing representation of a Keyed Stringed Instrument, from St Mary’s, Shrewsbury (primitive Clavichord). Before 1460.

for Aribo,[2] writing about fifty years after Guido, says that

few monochords were to be found without it. Had the clavichord

then been known, this makeshift

contrivance would not have

been used. Aribo strenuously endeavoured

to improve it, and “by

the grace of God” invented a monochord

measure which, on account of

the rapidity of the leaps he could

make with it, he named a wild-goat

(caprea). Jean de Muris (Musica

speculativa, 1323) teaches how true

relations may be found by a single-string

monochord, but recommends

a four-stringed one, properly a

tetrachord, to gain a knowledge of

unfamiliar intervals. He describes

the musical instruments known in

his time, but does not mention the

clavichord or monochord with keys,

which could not have been then

invented. Perhaps one of the earliest

forms of such an instrument, in which

stoppers or tangents had been

adopted from the organistrum, is

shown in fig. 1, from a wood carving

of a vicar choral or organist,

preserved in St Mary’s church,

Shrewsbury. The latest date to

which this interesting figure may be

attributed is 1460, but the conventional representation shows

that the instrument was then already of a past fashion, although

perhaps still retained in use and familiar to the carver.

In the Weimar Wunderbuch,[3] a MS. dated 1440, with pen and ink miniatures, is given a “clavichordium” having 8 short and apparently 16 long keys, the artist has drawn 12 strings in a rectangular case, but no tangents are visible. A keyboard of balanced keys existed in the little portable organ known as the regal, so often represented in old carvings, paintings and stained windows. Vitruvius, De architectura, lib. x. cap. xi., translated by Newton, describes a balanced keyboard; but the key apparatus is more particularly shown in The Pneumatics of Hero of Alexandria, translated by Bennet Woodcroft (London, 1851). In confirmation of this has been the remarkable recovery at Carthage[4] of a terra-cotta model of a Hydraulikon or water organ, dating from the 2nd century A.D., in which a balanced keyboard of 18 or 19 keys is shown. It seems likely the balanced keyboard was lost, and afterwards reinvented. The name of regal was derived from the rule (regula) or graduated scale of keys, and its use was to give the singers in religious processions the note or pitch. The only instrument of this kind known to exist in the United Kingdom is at Blair Atholl, and it bears the very late date of 1630. The Brussels regal[5] may be as modern. These are instances of how long a some-time admired musical instrument may remain in use after its first intention is forgotten. We attribute the adaptation of the narrow regal keyboard to what was still called the monochord, but was now a complex of monochords over one resonance board, to the latter half of the 14th century; it was accomplished by the substitution of tangents fixed in the future ends of the balanced keys for the movable bridges of the monochord or such stoppers as are shown in the Shrewsbury carving. Thus the monochordium or “payre of monochordis” became the clavichordium or “payre of clavichordis”—pair being applied, in the old sense of a “pair of steps,” to a series of degrees. This use of the word to imply gradation was common in England to all keyed instruments; thus we read, in the Tudor period and later, of a pair of regals, organs, or virginals. Ed. van der Straeten[6] reproduces a so-called clavichord of the 15th century from a MS. in the public library at Ghent. The treatise is anonymous, but other treatises in the same MS. bear dates 1503 and 1504. Van der Straeten is of opinion that the drawing may be assigned to the middle of the 15th century. The scribe calls the instrument a clavicimbalum, and this is undoubtedly correct; the 8 strings in the drawing are stretched from back to front over a long sound-board, the longest strings to the left; 8 keys, 4 long and 4 short with levers to which are attached the jacks, are seen in a horizontal line behind the keyboard, and behind them again are given the names of the notes a, b, c, d, e, f, g, h. In the Weimar Wunderbuch is a pen-and-ink sketch of the “clavicimbalum”[7] placed upon a table, in which we recognize the familiar outline of the harpsichord, but on a smaller scale. The keyboard shows white and black notes—the latter short keys, one between each group of two white keys, precisely as in the instrument reproduced by Van der Straeten—but no mechanism is visible under the strings.

The earliest known record of the clavichord occurs in some rules of the minnesingers,[8] dated 1404, preserved at Vienna. The monochord is named with it, showing a differentiation of these instruments, and of them from the clavicymbalum, the keyed cymbal, cembalo (Italian), or psaltery. From this we learn that a keyboard had been thus early adapted to that favourite medieval stringed instrument, the “cembalo” of Boccaccio, the “sautrie” of Chaucer. There were two forms of the psaltery: (1) the trapeze, one of the oldest representations of which is to be found in Orcagna’s famous Trionfo della Morte in the Campo Santo at Pisa, and another by the same painter in the National Gallery, London; and (2) the contemporary “testa di porco,” the pig’s head, which was of triangular shape as the name suggests. The trapeze psaltery was strung horizontally, the “istromento di porco” either horizontally or vertically—the notes, as in the common dulcimer, being in groups of three or four unisons. In these differences of form and stringing we see the cause of the ultimate differentiation of the spinet and harpsichord. The compass of the psalteries was nearly that of Guido’s scale; but according to Mersenne,[9] the lowest interval was a fourth, G to C, which is worthy of notice as anticipating the later “short measure”[10] of the spinet and organ.

The simplicity of the clavichord inclines us to place it, in order of time, before the clavicymbalum or clavicembalo; but we do not know how the sounds of the latter were at first excited. There is an indication as to its early form to be seen in the church of the Certosa near Pavia, which compares in probable date with the Shrewsbury example. We quote the reference to it from Dr Ambros.[11] He says a carving represents King David as holding an “istromento di porco” which has eight strings and as many keys lying parallel to them; inside the body of the instrument, which is open at the side nearest the right hand of King David, he touches the keys with the right hand and damps the strings with the left. The attribution of archaism applies with equal force to this carving as to the Shrewsbury one, for when the monastery of Certosa near Pavia was built by Ambrogio Fossana in 1472, chromatic keyboards, which imply a considerable advance, were already in use. There is an authentic representation of a chromatic keyboard, painted not later than 1426, in the St Cecilia panel (now at Berlin) of the famous Adoration of the Lamb by the Van Eycks. The instrument depicted is a positive organ, and it is interesting to notice in this realistic painting that the keys are evidently boxwood, as in the Italian spinets of later date, and that the angel plays a common chord—A with the right hand, F and C with the left. But diatonic organs with eight steps or keys in the octave, which included the B flat and the B natural, as in Guido’s scale, were long preserved, for Praetorius speaks of them as still existing nearly two hundred years later. This diatonic keyboard, we learn from Sebastian Virdung (Musica getutscht und auszgezogen, Basel, 1511), was the keyboard of the early clavichord. We reproduce his diagram as the only authority we have for the disposition of the one short key.

|

| Fig. 2.—Diatonic Clavichord Keyboard (Guido’s Scale) from Virdung. Before 1511. |

The extent of this scale is exactly Guido’s. Virdung’s diagram of the chromatic is the same as our own familiar keyboard, and comprises three octaves and a note, from F below the bass stave to G above the treble. But Virdung tells us that even then clavichords were made longer than four octaves by repetition of the same order of keys. The introduction of the chromatic order he attributes to the study of Boetius, and the consequent endeavour to restore the three musical genera of the Greeks—the diatonic, chromatic and enharmonic. But the last-named had not been attained. Virdung gives woodcuts of the clavichordium, the virginal, the clavicymbalum and the clavicytherium. We reproduce three of them (figs. 3, 6 and 12), omitting the virginal as obviously incorrect. Writers on musical instruments have continually repeated these drawings without discerning that in the printing they are reversed, which puts the keyboards entirely wrong, and that in Luscinius’s Latin translation of Virdung (Musurgia, sive praxis musicae, Strasburg, 1536), which has been hitherto chiefly followed, two of the engravings, the clavicimbalum and the clavicytherium, are transposed, another cause of error. Martin Agricola (Musica instrumentalis, Wittenberg, 1529) has copied Virdung’s illustrations with some differences of perspective, and the addition, here and there, of errors of his own.

|

| Fig. 3.—Virdung’s Clavichordium, 1511; reversed facsimile. |

Still vulgarly known as monochord, Virdung’s clavichord was really a box of monochords, all the strings being of the same length. He derives the clavichord from Guido’s monochord as he does the virginal from the psaltery, but, at the same time, confesses he does not know when, or by whom, either instrument was invented. We observe in this drawing the short sound-board, which always remained a peculiarity of the clavichord, and the straight sound-board bridge—necessarily so when all the strings were of one length. To gain an angle of incidence for the tangents against the strings the keys were made crooked, an expedient further rendered necessary by the “fretting”—three tangents, according to Virdung, being directed to stop as many notes from each single group of three strings tuned in unison; each tangent thus made a different vibrating length of string. In the drawing the strings are merely indicated. The German for fret is Bund, and such a clavichord, in that language, is known as a “gebundenes Clavichord” both fret (to rub) and Bund (from binden, to bind) having been taken over from the lute or viol. The French and Italians employ “touche” and “tasto,” touch. Praetorius who wrote a hundred years later than Virdung, says two, three and four tangents were thus employed in stopping. There are extant small clavichords having three keys and tangents to one pair of strings and others have no more than two tangents to a note formed by a pair of strings, instead of three. Thus seven pairs of strings suffice for an octave of twelve keys, the open notes being F, G, A, B flat, C, D, E flat, and by an unexplained peculiarity, perhaps derived from some special estimation of the notes which was connected with the church modes, A and D are left throughout free from a second tangent. A corresponding value of these notes is shown by their independence of chromatic alteration in tuning the double Irish harp, as explained by Vincentio Galilei in his treatise on music (Dialogo della musica, Florence, 1581). Adlung, who died in 1762, speaks of another fretting, but it must have been an adaptation to the modern major scale, the “free” notes being E and B. Clavichords were made with double fretting up to about the year 1700—that is to say, to the epoch of J. S. Bach, who, taking advantage of its abolition and the consequent use of independent pairs of strings for each note, was enabled to tune in all keys equally, which had been impossible so long as the fretting was maintained. The modern scales having become established, Bach was now able to produce, in 1722, Das wohltemperirte Clavier, the first collection of preludes and fugues in all the twenty-four major and minor scales for a clavichord which was tuned, as to concordance and dissonance, fairly equal.

|

| Fig. 4.—Manicordo (Clavichord) d’Eleonora di Montalvo, 1659; Kraus Museum, Florence. |

The oldest clavichord, here called manicordo (as French manicorde, from monochord), known to exist is that shown in fig. 4. It will be observed that the lowest octave is here already “bundfrei” or fret-free. The strings are no longer of equal length, and there are three bridges, divisions of the one bridge, in different positions on the sound-board. Mersenne’s “manicorde” (Harmonie universelle, Paris 1636, p. 115), shown in an engraving in that work, has the strings still nearly of equal length, but the sound-board bridge is divided into five. The fretted clavichords made in Germany in the last years of the 17th century have the curved sound-board bridge, like a spinet. In the clavichord the tangents always form the second bridge, indispensable for the vibration, besides acting as the sound exciters (fig. 5). The common damper to all the strings is a list of cloth, interwoven behind the tangents. As the tangents quitted the strings the cloth immediately stopped all vibration. Too much cloth would diminish the tone of this already feeble instrument, which gained the name of “dumb spinet” from its use. In the clavichord in Rubens’s St Cecilia (Dresden Gallery)—interesting as perhaps representing that painter’s own instrument—the damping cloth is accurately painted. The number of keys there shown is three octaves and a third, F to A—the same extent as in Handel’s clavichord now in the museum at Maidstone (an Italian instrument dated 1726, and not fretted), but with the peculiarity of a combined chromatic and short octave in the lowest notes, to which we shall have to refer when we arrive at the spinet; we pass it by as the only instance we have come across in the clavichord.

|

| Fig. 5.—Clavichord Tangent. |

The clavichord must have gone out of favour in Great Britain and the Netherlands early in the 16th century, before its expressive power, which is of the most tender and intimate quality, could have been, from the nature of the music played, observed,—the more brilliant and elegant spinet being preferred to it. Like the other keyboard instruments it had no German name, and can hardly have been of German origin. Holbein, in his drawing of the family of Sir Thomas More, 1528, now at Basel, indicates the place for “Klavikordi und ander Seytinspill.” But it remained longest in use in Germany—until even the beginning of the 19th century. It was the favourite “Klavier” of the Bachs. Besides that of Handel already noticed there are in existence clavichords the former possession of which is attributed to Mozart and Beethoven. The clavichord was obedient to a peculiarity of touch possible on no other keyboard instrument. This is described by C. P. Emmanuel Bach in his famous essay on playing and accompaniment, entitled Versuch über die wahre Art das Klavier zu spielen (“An Essay on the True Way to play Keyboard Instruments.”) It is the Bebung (trembling), a vibration in a melody note of the same nature as the tremolo frequently employed by violin players to heighten the expressive effect; it was gained by a repeated movement of the fleshy end of the finger while the key was still held down. The Bebung was indicated in the notation by dots over the note to be affected by it, perhaps showing how many times the note should be repeated. According to the practice of the Bachs, as handed down to us in the above mentioned essay, great smoothness of touch was required to play the clavichord in tune. As with the monochord, the means taken to produce the sound disturbed the accuracy of the string measurement by increasing tension, so that a key touched too firmly in the clavichord, by unduly raising the string, sharpened the pitch, an error in playing deprecated by C. P. Emmanuel Bach. This answers the assertion which has been made that J. S. Bach could not have been nice about tuning when he played from preference on an instrument of uncertain intonation.

The next instrument described by Virdung is the virginal (virginalis,

proper for a girl), a parallelogram in shape, having the same

projecting keyboard and compass of keys the same as

the clavichordium. Here we can trace derivation from

the psaltery in the sound-board covering the entire inner surface

of the instrument and in the triangular disposition of the strings.

Virginal.

Clavicimbalum.

The virginal in Virdung’s drawing has an impossible position with

reference to the keyboard, which renders its reproduction as an

illustration useless. But in the next drawing, the clavicimbalum,

this is rectified, and the drawing, reversed on

account of the keyboard, can be accepted as roughly

representing the instrument so called (fig. 6). There would be no difference between it and the virginal were it not for a peculiarity

of keyboard compass, which emphatically refers itself to

the Italian “spinetta,” a name unnoticed by Virdung or by his

countryman Arnold Schlick, who, in the same year 1511, published

his Spiegel der Orgelmacher (Organ-builders’ Mirror),

and named the clavichordium and clavicimbalum as familiar

instruments. In the first place, the keyboard, beginning apparently

with B natural, instead of F, makes the clavicimbalum

smaller than the virginal, the strings in this arrangement being

shorter; in the next place it is almost certain that the Italian

spinet compass, beginning apparently upon a semitone, is

identical with a “short measure” or “short octave” organ

compass, a very old keyboard arrangement, by which the lowest

note, representing B, really sounded G and C sharp in like

manner A. The origin of this may be deduced from the psaltery

and many representations of the regal, and its object appears

to have been to obtain dominant basses for cadences, harmonious

closes having early been sought for as giving pleasure to the ear.

Authority for this practice is to be found in Mersenne, who, in

1636, expressly describes it as occurring in his own spinet

(espinette). He says the keyboards of the spinet and organ are

the same.

|

| Fig. 6.—Virdung’s Clavicimbalum (Spinet), 1511; reversed facsimile. |

Now, in his Latin edition of the same work he renders

espinette by clavicimbalum. We read (Harmonie Universelle,

Paris, 1636, liv. 3, p. 107—“Its longest string [his spinet’s] is

little more than a foot in length between the two bridges. It

has only thirty-one keys [marches] in its keyboard, and as

many strings over its sound-board [he now refers to the illustration],

so that there are five keys hidden on account of the perspective—that

is to say, three diatonic and two chromatic [feintes,

same as the Latin ficti], of which the first is cut into two

[a divided sharp forming two keys]; but these sharps serve to

go down to the third and fourth below the first step, C sol [tenor

clef C], in order to go as far as the third octave, for the eighteen

principal steps make but an eighteenth, that is to say, a fourth

more than two octaves.” The note we call F, he, on his engraving,

letters as C, indicating the pitch of a spinet of the second

size, which the one described is not. The

third and fourth, reached by his divided sharp,

are consequently the lower A and G; or, to

complete, as he says, the third octave, the

lowest note might be F, but for that he would

want the diatonic semitone B, which his spinet,

according to his description, did not possess.[12]

Mersenne’s statement sufficiently proves, first,

the use in spinets as well as in organs of what

we now call “short measure,” and, secondly,

the object of divided sharps at the lower end

of the keyboard to gain lower notes. He

speaks of one string only to each note; unlike

the double and triple strung clavichord, those

instruments, clavicimbalum, spinet, or virginal,

derived from the psaltery, could only present

one string to the mechanical plectrum which

twanged it. As regards the kind of plectra

Fig. 7.—Spinet “Jack.”

earliest used we have no evidence. The little crow-quill points

project from centred tongues in uprights of wood known as

“jacks” (fig. 7), which also carry the dampers, and rising by

the depression of the keys in front, the quills set the strings

vibrating as they pluck them in passing, springs at first of steel,

later of bristle, giving energy to the twang and governing their

return J. C. Scaliger in Poetices libri septem (1561, p. 51. c. 1.)

states that the Clavicimbalum and Harpichordum of his

boyhood are now called Spinets on account of those quill

points (ab illis mucronibus), and attributes the introduction

of the name “spinetta” to them (from spina, a thorn). We will

leave harpichordum for the present, but the early identity

Spinet.

of clavicimbalum and spinetta is certainly proved.

Scaliger’s etymology remained unquestioned until

Signor Ponsicchi of Florence discovered another derivation.

He found in a rare book entitled Conclusione nel suono dell’

organo, di D. Adriano Banchieri (Bologna, 1608), the following

passage, which translated reads: “Spinetta was thus named

from the inventor of that oblong form, who was one Maestro

Giovanni Spinetti, a Venetian; and I have seen one of

those instruments, in the possession of Francesco Stivori,

organist of the magnificent community of Montagnana,

within which was this inscription—Joannes Spinetvs Venetvs

fecit, A.D. 1503.” Scaliger’s and Banchieri’s statements may

be combined, as there is no discrepancy of dates, or we may

rely upon whichever seems to us to have the greater authority,

always bearing in mind that neither invalidates the other. The

introduction of crow-quill points, and adaptation to an oblong

case of an instrument previously in a trapeze form, are synchronous;

but we must accept 1503 as a late date for one of Spinetti’s

instruments, seeing that the altered form had already become

common, as shown by Virdung, in another country as early as

1511. After this date there are frequent references to spinets in

public records and other documents, and we have fortunately the

instruments themselves to put in evidence, preserved in public

museums and in private collections. A spinet dated 1490 was

shown at Bologna in 1888; another old spinet in the Conservatoire,

Paris, is a pentagonal instrument made by Francesco di

Portalupis at Verona, 1523. The Milanese Rossi were famous

spinet-makers, and have been accredited (La Nobilità di Milano,

1595) with an improvement in the form which we believe was

the recessing of the keyboard, a feature which had previously

entirely projected; by the recessing a greater width was obtained

for the sound-board. The spinets by Annibale Rosso at South

Kensington, dated respectively 1555 (fig. 8) and 1577, show this

alteration, and may be compared with the older and purer form

of one, dated 1568, by Marco Jadra (also known as Marco “dalle

spinette,” or “dai cembali”). Besides the pentagonal spinet,

there was an heptagonal variety; they had neither covers nor

stands, and were often withdrawn from decorated cases when

required for performance. In other instances, as in the 1577

Rosso spinet, the case of the instrument itself was richly adorned.

The apparent compass of the keyboard in Italy generally

exceeded four octaves by a semitone, E to F; but we may regard

the lowest natural key as usually C, and the lowest sharp key

as usually D, in these instruments, according to “short measure.”

|

| Fig. 8.—Milanese Spinetta, by Annibale Rosso, 1555; South Kensington Museum. |

The rectangular spinet, Virdung’s “virginal,” early assumed in Italy the fashion of the large “cassoni” or wedding chests. The oldest we know of in this style, and dated, is the fine specimen belonging to M. Terme which figures in L’Art decoratif (fig. 9). Virginal is not an Italian name; Clavecin. the rectangular instrument in Italy is “spinetta tavola.” In England, from Henry VII. to Charles II., all quilled instruments (stromenti di penna), without distinction as to form, were known as virginals. It was a common name, equivalent to the contemporary Italian clavicordo and Flemish clavisingel. From the latter, by apocope, we arrive at the French clavecin—the French clavier (clavis, a key), a keyboard, being in its turn adopted by the Germans to denote any keyboard stringed instrument.

|

| Fig. 9.—Spinetta Tavola (Virginal), 1568; Vict. and Albert Museum. |

Mersenne (op. cit., liv. iii., p. 158) gives three sizes for spinets—one 21/2 ft. wide, tuned to the octave of the “ton de chapelle” (in his day a half tone above the present English medium pitch), one of 31/2 ft. tuned to the fourth below, and one of 5 ft. tuned to the octave below the first, the last being therefore tuned in unison to the chapel pitch. He says his own spinet was one of the smallest it was customary to make, but from the lettering of the keys in his drawing it would have been of the second size, or the spinet tuned to the fourth. The octave spinet, of trapeze form, was known in Italy as “ottavina” or “spinetta di serenata.” It had a less compass of keys than the larger instrument, being apparently three and two-third octaves, E to C—which by the “short measure” would be four octaves, C to C. We learn from Praetorius that these little spinets were placed upon the larger ones in performance; their use was to heighten the brilliant effect. In the double rectangular clavisingel of the Netherlands, in which there was a movable octave instrument, we recognize a similar intention. There is a fine spinet of this kind at Nuremberg. Praetorius illustrates the Italian spinet by a form known as the “spinetta traversa,” an approach towards the long clavicembalo or harpsichord, the tuning pins being immediately over the keyboard. This transposed spinet, more powerful than the old trapeze one, became fashionable in England after the Restoration, Haward, Keene, Slade, Player, Baudin, the Hitchcocks, Mahoon, Haxby, the Harrir family, and others having made such “spinets” during a period for which we have dates from 1664 to 1784. Pepys bought his “Espinette” from Charles Haward for £5, July 13, 1664.

|

| Fig. 10.—English Spinet (Spinetta Traversa), by Carolus Haward. About 1668. |

The spinets of Keene and Player, made about 1700, have frequently two divided sharps at the bass end of the keyboard, as in the description by Mersenne, quoted above, of a spinet with short measure. Such divided sharps have been assumed to be quarter tones, but enharmonic intervals in the extreme bass can have no justification. From the tuning of Handel’s Italian clavichord already mentioned, which has this peculiarity, and from Praetorius we find the further halves of the two divided sharps were the chromatic semitones, and the nearer halves the major thirds below i.e. the dominant fourths to the next natural keys. Thomas Hitchcock (for whom there are dates 1664 and 1703 written on keys and jacks of spinets bearing Edward Blunt’s name and having divided bass sharps) made a great advance in constructing spinets, giving them the wide compass of five octaves, from G to G, with very fine keyboards in which the sharps were inlaid with a slip of the ivory or ebony, as the case might be, of the naturals. Their instruments, always numbered, and not dated as has been sometimes supposed, became models for contemporary and subsequent English makers.

We have now to ask what was the difference beween Scaliger’s harpichordum and his clavicymbal. Galilei, the father of the astronomer of that name (Dialogo della musica antica e moderna, Florence, 1581), says that the harpichord was so named from having resembled an “arpa giacente,” a prostrate or “couched” harp, proving that the clavicymbal was at first the Harpsichord; Clavicymbal. trapeze-shaped spinet; and we should therefore differentiate harpichord and clavicymbal as, in form, suggested by or derived from the harp and psaltery, or from a “testa di porco” and an ordinary trapeze psaltery. We are inclined to prefer the latter. The Latin name “clavicymbalum,” having early been replaced by spinet and virginal, was in Italy and France bestowed upon the long harpichord, and was continued as clavicembalo (gravecembalo, or familiarly cembalo only) and clavecin. Much later, after the restoration of the Stuarts, the first name was accepted and naturalized in England as harpsichord, which we will define as the long instrument with quills, shaped like a modern grand piano, and resembling a wing, from which it has gained the German appellation “Flügel.” We can point out no long instrument of this kind so old as the Roman cembalo at South Kensington (fig. 11). It was made by Geronimo of Bologna in 1521, two years before the Paris Portalupis spinet. The outer case is of finely tooled leather. It has a spinet keyboard with a compass of nearly four octaves, E to D. The natural keys are of boxwood, gracefully arcaded in front. The keyboard of the Italian cembalo was afterwards carried out to the normal four octaves. There is an existing example, dated 1626, with the bass keys carried out without sharps in long measure (unfortunately altered by a restorer). It is surprising to see with what steady persistence the Italians adhered to their original model in making the instrument. As late as the epoch of Cristofori,[13] and in his 1722 cembalo at Florence,[14] we still find the independent outer case, the single keyboard, the two unisons, without power to reduce to one by using stops. The Italians have been as conservative with their forms of spinet, and are to this day with their organs. The startling “piano e forte” of 1598, brought to light from the records of the house of D’Este by Count Valdrighi of Modena,[15] after much consideration and a desire to find in it an anticipation of Cristofori’s subsequent invention of the pianoforte, we are disposed to regard as an ordinary cembalo with power to shift, by a stop, from two unisons (forte) to one string (piano), at that time a Flemish practice, and most likely brought to Italy by one of the Flemish musicians who founded the Italian school of composition. About the year 1600, when accompaniment was invented for monody, large cembalos were made for the orchestras to bring out the bass part, the performer standing to play. Such an instrument was called “archicembalo,”[16] a name also applied to a large cembalo, made by Vito Trasuntino, a Venetian, in 1606, intended by thirty-one keys in each of its four octaves—one hundred and twenty-five in all—to restore the three genera of the ancient Greeks. How many attempts have been made before and since Trasuntino to purify intonation in keyboard instruments by multiplying keys in the octave? Simultaneously with Father Smith’s well-known experiment in the Temple organ, London, there were divided keys in an Italian harpsichord to gain a separate G sharp and A flat, and a separate D sharp and E flat.

|

| Fig. 11.—Roman Clavicembalo by Geronimo of Bologna, 1521; Vict. and Albert Museum. |

Double keyboards and stops in the long cembalo or harpsichord

came into use in the Netherlands early in the 16th century. We

find them imported into England. The following citations,

quoted by Rimbault in his History of the Pianoforte, but

imperfectly understood by him, are from the privy purse expenses

of King Henry VIII., as extracted by Sir Harris Nicolas in

1827.

|

|

Fig. 12.—Virdung’s Clavicytherium (upright Harpsichord), 1511; (reversed facsimile). |

“1530 (April). Item the vj daye paied to William Lewes for ii payer of virginalls in one coffer with iiii stoppes brought to Grenewiche iii li. And for ii payer of virginalls in one coffer brought to the More other iii li.”

Now the second instrument may be explained, virginals meaning any quilled instrument, as a double spinet, like that at Nuremberg by Martin van der Beest, the octave division being movable. But the first cannot be so explained; the four stops can only belong to a harpsichord, and the two pair instrument to a double-keyed one, one keyboard being over, and not by the side of the other. Again from the inventory after the king’s death (see Brit. Mus. Harl. MS. 1419) fol. 247—

“Two fair pair of new long Virginalls made harp-fashion of Cipres, with keys of ivory, having the King’s Arms crowned and supported by his Grace’s beastes within a garter gilt, standing over the keys.”

We are disposed to believe that we have here another double keyboard harpsichord. Rimbault saw in this an upright instrument, such as Virdung’s clavicytherium (fig. 12). Having since seen the one in the Kraus Museum, Florence, it seems that Virdung’s drawing should not have been reversed; but he has mistaken the wires acting upon the jacks for strings, and omitted the latter stretched horizontally across the soundboard (see Clavicytherium). We read in an inventory of the furniture of Warwick Castle, 1584, “a faire paire of double virginalls,” and in the Hengrave inventory, 1603, “one great payre of double virginalls.” Hans Ruckers, the great clavisingel maker of Antwerp, lived too late to have invented the double keyboard and stops, evident adaptions from the organ, and the octave string (the invention of which was so long attributed to him), which incorporated the octave spinet with the large instrument, to be henceforth playable without the co-operation of another performer, was already in use when he began his work. Until the last harpsichord was made by Joseph Kirkman, in 1798, scarcely an instrument of the kind was constructed, except in Italy, without the octaves. The harpsichord as known throughout the 18th century, with piano upper and forte lower keyboard, was the invention of Hans Ruckers’s grandson, Jean Ruckers’s nephew, Jan Couchet, about 1640. Before that time the double keyboards in Flemish harpsichords were merely a transposing expedient, to change the pitch a fourth, from plagal to authentic and vice versa, while using the same groups of keys. Fortunately there is a harpsichord existing with double keyboards unaltered, date 1638, belonging to Sir Bernard Samuelson, formerly in the possession of Mr Spence, of Florence, made by Jean Ruckers, the keyboards being in their original position. It was not so much invention as beauty of tone which made the Ruckers’ harpsichords famous. The Ruckers harpsichords in the 18th century were fetching such prices as Bologna lutes did in the 17th or Cremona violins do now. There are still many specimens existing in Belgium, France and England. Handel had a Ruckers harpsichord, now in Buckingham Palace; it completes the number of sixty-three existing Ruckers instruments catalogued in Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

After the Antwerp make declined, London became pre-eminent for harpsichords the representative makers being Jacob Kirckmann and Burckhard Tschudi, pupils of a Flemish master, one Tabel, who had settled in London, and whose business Kirckmann continued through marriage with Tabel’s widow. Tschudi was of a noble Swiss family belonging to the canton of Glarus. According to the custom with foreign names obtaining at that time, by which Haendel became Handel, and Schmidt Smith, Kirckmann dropped his final n and Tschudi became Shudi, but he resumed the full spelling in the facies of the splendid harpsichords he made in 1766 for Frederick the Great, which are still preserved in the New Palace, Potsdam. By these great makers the harpsichord became a larger, heavier-strung and more powerful instrument, and fancy stops were added to vary the tone effects. To the three shifting registers of jacks of the octave and first and second unisons were added the “lute,” the charm of which was due to the favouring of high harmonics by plucking the strings close to the bridge, and the “harp,” a surding or muting effect produced by impeding the vibration of the strings by contact of small pieces of buff leather. Two pedals were also used, the left-hand one a combination of a unison and lute. This pedal, with the “machine” stop, reduced the upper keyboard to the lute register, the plectra of which acted upon the strings near the wrest-plank bridge only, the lower keyboard to the second unison. Releasing the machine stop and quitting the pedal restores the first unison on both keyboards and the octave on the lower. The right-hand pedal was to raise a hinged portion of the top or cover and thus gain some power of “swell” or crescendo, an invention of Roger Plenius,[17] to whom also the harp stop may be rightly attributed. This ingenious harpsichord maker had been stimulated to gain these effects by the nascent pianoforte which, as we shall find, he was the first to make in England. The first idea of pedals for the harpsichord to act as stops appears to have been John Hayward’s (?Haward) as early as 1676, as we learn from Mace’s Musick’s Monument, p. 235. The French makers preferred a kind of knee-pedal arrangement, known as the “genouillère,” and sometimes a more complete muting by one long strip of buff leather, the “sourdine.” As an improvement upon Plenius’s clumsy swell, Shudi in 1769 patented the Venetian swell, a framing of louvres, like a Venetian blind, which opened by the movement of the pedal, and becoming in England a favourite addition to harpsichords, was early transferred to the organ, in which it replaced the rude “nag’s-head” swell. A French harpsichord maker, Marius, whose name is remembered from a futile attempt to design a pianoforte action, invented a folding harpsichord, the “clavecin brisé,” by which the instrument could be disposed of in a smaller space. One, which is preserved at Berlin, probably formed part of the camp baggage of Frederick the Great.

It was formerly a custom with kings, princes and nobles

to keep large collections of musical instruments for actual

playing purposes, in the domestic and festive music of their

courts. There are records of their inventories,

and it was to keep such a collection in playing order

that Prince Ferdinand dei Medici engaged a Paduan

Cristofori’s invention

of the Pianoforte.

harpsichord maker, Bartolommeo Cristofori, the

man of genius who invented and produced the pianoforte.[18]

We fortunately possess the record of this invention in a

literary form from a well-known writer, the Marchese Scipione

Maffei; his description appeared in the Giornale dei letterati

d’Italia, a publication conducted by Apostolo Zeno. The

date of Maffei’s paper was 1711. Rimbault reproduced it,

with a technically imperfect translation, in his History of the

Pianoforte. We learn from it that in 1709 Cristofori had

completed four “gravecembali col piano e forte”—keyed-psalteries

with soft and loud—three of them being of the long

or usual harpsichord form. A synonym in Italian for the

original cembalo (or psaltery) is “salterio,” and if it were struck

with hammers it became a “salterio tedesco” (the German

hackbrett, or chopping board), the latter being the common

dulcimer. Now the first notion of a pianoforte is a dulcimer

with keys, and we may perhaps not be wrong in supposing that

there had been many attempts and failures to put a keyboard

to a dulcimer or hammers to a harpsichord before Cristofori

successfully solved the problem. The sketch of his action in

Maffei’s essay shows an incomplete stage in the invention,

although the kernel of it—the principle of escapement or the

controlled rebound of the hammer—is already there. He obtains

it by a centred lever (linguetta mobile) or hopper, working, when

the key is depressed by the touch, in a small projection from

the centred hammer-butt. The return, governed by a spring,

must have been uncertain and incapable of further regulating

than could be obtained by modifying the strength of the spring.

Moreover, the hammer had each time to be raised the entire

distance of its fall. There are, however, two pianofortes by

Cristofori, dated respectively 1720 and 1726, which show a

much improved, we may even say a perfected, construction,

for the whole of an essential piano movement is there. The

earlier instrument (now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York)

has undergone considerable restoration, the original hollow

hammer-head having been replaced by a modern one, and the

hammer-butt, instead of being centred by means of the holes

provided by Cristofori himself for the purpose, having been

lengthened by a leather hinge screwed to the block;[19] but the

1726 one, which is in the Kraus Museum at Florence, retains

the original leather hammer-heads. Both instruments possess

alike a contrivance for determining the radius of the hopper,

and both have been unexpectedly found to have the “check”

(Ital. paramartello), which regulates the fall of the hammer

according to the strength of the blow which has impelled it to

the strings. After this discovery of the actual instruments of

Cristofori there can be no longer doubt as to the attribution of

the invention to him in its initiation and its practical completion

with escapement and check. To Cristofori we are indebted,

not only for the power of playing piano and forte, but for

the infinite variations of tone, or nuances, which render the

instrument so delightful.

|

| Fig. 13.—Cristofori’s Escapement Action, 1720. Restored in 1875 by Cesare Ponsicchi. |

|

| Fig. 14.—Cristofori’s Piano e Forte, 1726; Kraus Museum, Florence. |

But his problem was not solved by the devising of a working action; there was much more to be done to instal the pianoforte as a new musical instrument. The resonance, that most subtle and yet all-embracing factor, had been experimentally developed to a certain perfection by many generations of spinet and harpsichord makers, but the resistance structure had to be thought out again. Thicker stringing, rendered indispensable to withstand even Cristofori’s light hammers, demanded in its turn a stronger framing than the harpsichord had needed. To make his structure firm he considerably increased the strength of the block which holds the tuning-pins, and as he could not do so without materially adding to its thickness, he adopted the bold expedient of inverting it; driving his wrest-pins, harp-fashion, through it, so that tuning was effected at their upper, while the wires were attached to their lower, ends. Then, to guarantee the security of the case, he ran an independent string-block round it of stouter wood than had been used in harpsichords, in which block the hitch-pins were driven to hold the farther ends of the strings, which were spaced at equal distances (unlike the harpsichord), the dampers lying between the pairs of unisons.

Cristofori died in 1731. He had pupils,[20] but did not found a school of Italian pianoforte-making, perhaps from the peculiar Italian conservatism in musical instruments we have already remarked upon. The essay of Scipione Maffei was translated into German, in 1725, by König, the court poet at Dresden, and friend of Gottfried Silbermann, the renowned organ builder and harpsichord and clavichord maker.[21] Incited by this publication, and perhaps by having seen in Dresden one of Silbermann. Cristofori’s pianofortes, Silbermann appears to have taken up the new instrument, and in 1726 to have manufactured two, which J. S. Bach, according to his pupil Agricola, pronounced failures. The trebles were too weak; the touch was too heavy. There has long been another version to this story, viz. that Silbermann borrowed the idea of his action from a very simple model contrived by a young musician named Schroeter, who had left it at the electoral court in 1721, and, quitting Saxony to travel, had not afterwards claimed it. It may be so; but Schroeter’s letter, printed in Mitzler’s Bibliothek, dated 1738, is not supported by any other evidence than the recent discovery of an altered German harpsichord, the hammer action of which, in its simplicity, may have been taken from Schroeter’s diagram, and would sufficiently account for the condemnation of Silbermann’s earliest pianofortes if he had made use of it. In either case it is easy to distinguish between the lines of Schroeter’s interesting communications (to Mitzler, and later to Marpurg) the bitter disappointment he felt in being left out of the practical development of so important an instrument.

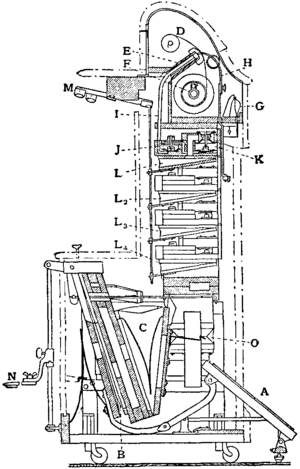

But, whatever Silbermann’s first experiments were based upon, it was ascertained, by the investigations of A. J. Hipkins, that he, when successful, adopted Cristofori’s pianoforte without further alteration than the compass and colour of the keys and the style of joinery of the case. In the Silbermann grand pianofortes, in the three palaces at Potsdam, known to have been Frederick the Great’s, and to have been acquired by that monarch prior to J. S. Bach’s visit to him in 1747, we find the Cristofori framing, stringing, inverted wrest-plank and action complete. Fig. 15 represents the instrument on which J. S. Bach played in the Town Palace, Potsdam.

|

| Fig. 15.—Silbermann Forte Piano; Stadtschloss, Potsdam, 1746. |

|

| Fig. 16.—Frederici’s Upright Grand Piano Action, 1745. In the museum of the Brussels Conservatoire. |

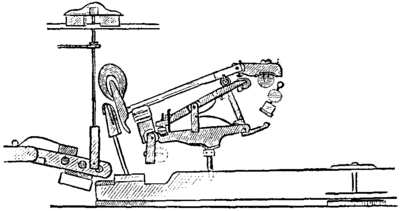

It has been repeatedly stated in Germany that Frederici, of Gera in Saxony, an organ builder and musical instrument maker, invented the square or table-shaped piano, the “fort bien,” as he is said to have called it, about 1758–1760. No square piano by this maker is forthcoming, though an “upright grand” piano, made by Domenico del Frederici. Mela in 1739, with an action adapted from Cristofori’s has been discovered by Signor Ponsicchi of Florence. Victor Mahillon of Brussels, however, acquired a Frederici “upright grand” piano, dated 1745 (fig. 16). In Frederici’s upright grand action we have not to do with the ideas of either Cristofori or Schroeter; the movement is practically identical with the hammer action of a German clock, and has its counterpart in a piano at Nuremberg; a fact which needs further elucidation. We note here the earliest example of the leather hinge, afterwards so common in piano actions and only now going out of use. Where are we to look for Schroeter’s copyist if not found in Silbermann, Frederici, or, as we shall presently see, perhaps J. G. Wagner? It might be in the harpsichord we have mentioned, which, made in 1712 by one Brock for the elector of Hanover (afterwards George I. of England), was by him presented to the Protestant pastor of Schulenberg, near Hanover, and has since been rudely altered into a pianoforte (fig. 17). There is an altered harpsichord in the museum at Basel which appears to have been no more successful. But an attempted combination of harpsichord and pianoforte appears as a very early intention. The English poet Mason, the friend of Gray, bought such an instrument at Hamburg in 1755, with “the cleverest mechanism imaginable.”

|

| Fig. 17.—Hammer and Lifter of altered Harpsichord by Brock. Instrument in the collection of Mr Kendrick Pyne, Manchester. |

It was only under date of 1763 that Schroeter[22] published for the first time a diagram of his proposed invention, designed more than forty years before. It appeared in Marpurg’s Kritische Briefe Schroeter; Zumpe. (Berlin, 1764). Now, immediately after, Johann Zumpe, a German in London, who had been one of Shudi’s workmen, invented or introduced (for there is some tradition that Mason had to do with the invention of it)[23] a square piano, which was to become the most popular domestic instrument. It would seem that Zumpe was in fact not the inventor of the square piano, which appears to have been well known in Germany before his date, a discovery made by Mr George Rose. In Paul de Wit’s Musical Instrument Museum—formerly in Leipzig, now transferred to Cologne—there is a small square piano, 27 in. long, 10 in. wide and 41/2 in. high, having a contracted keyboard of 3 octaves and 2 notes. The action of this small instrument is practically identical in every detail with that of the square pianofortes made much later by Zumpe (Paul de Wit, Katalog des musikhistorischen Museums, Leipzig, 1903. No. 55, illustration, p. 38). Inside is inscribed: “Friedrich Hildebrandt, Instrumentenmacher in Leipzig, Quergasse,” with four figures almost illegible. Paul de Wit refers the instrument to the middle of the 18th century. It has all the appearance of being a reduced copy of a well-established type, differing very little from the later models, except that it has no dampers. It seems probable that this small instrument is a converted clavichord, and that the action may have been suggested by Schroeter’s model, left in 1721 at the Electoral Court of Saxony. Burney tells us all about Zumpe; and his instruments still existing would fix the date of the first at about 1765. Fetis narrates, however, that he began the study of the piano on a square piano made by Zumpe in 1762. In his simple “old man’s head” action we have the nearest approach to a realization of Schroeter’s simple idea. It will be observed that Schroeter’s damper would stop all vibration at once. This defect is overcome by Zumpe’s “mopstick” damper.

|

| Fig. 18.—Schroeter’s Model for an Action, 1721. |

Another piano action had, however, come into use about that time or even earlier in Germany. The discovery of it in the simplest form is to be attributed to V. C. Mahillon, who found it in a square piano belonging to Henri Gosselin, painter, of Brussels. The principle of this action is that which was later perfected by the addition of a good escapement Stein. by Stein of Augsburg, and was again later experimented upon by Sebastian Erard. Its origin is perhaps due to the contrivance of a piano action that should suit the shallow clavichord and permit of its transformation into a square piano; a transformation, Schroeter tells us, had been going on when he wrote his complaint. It will be observed that the hammer is, as compared with other actions, reversed, and the axis rises with the key, necessitating a fixed means for raising the hammer, in this action effected by a rail against which the hammer is jerked up. It was Stein’s merit to graft the hopper principle upon this simple action; and Mozart’s approbation of the invention, when he met with it at Augsburg in 1777, is expressed in a well-known letter addressed to his mother. No more “blocking” of the hammer, destroying all vibration, was henceforth to vex his mind. He had found the instrument that for the rest of his short life replaced the harpsichord. V. C. Mahillon secured for his museum the only Johann Andreas Stein piano which is known to remain. It is from Augsburg, dated 1780, and has Stein’s escapement action, two unisons, and the knee pedal, then and later common in Germany.

|

| Fig. 19.—Zumpe’s Square Piano Action, 1766. |

|

| Fig. 20.—Old Piano Action on the German principle of Escapement. Square Piano belonging to M. Gosselin, Brussels. |

Mozart’s own grand piano, preserved at Salzburg, and the two grand pianos (the latest dated 1790) by Huhn of Berlin, preserved at Berlin and Charlottenburg, because they had belonged to Queen Luise of Prussia, follow Stein in all particulars. These instruments have three unisons upwards, and the muting movement known as celeste, which no doubt Stein had also. The wrest-plank is not inverted; nor is there any imitation of Cristofori. We may regard Stein, coming after the Seven Years’ War which had devastated Saxony, as the German reinventor of the grand piano. Stein’s instrument was accepted as a model, as we have seen, in Berlin as well as Vienna, to which city his business was transferred in 1794 by his daughter Nanette, known as an accomplished pianist and friend of Beethoven, who at that time used Stein’s pianos. She had her brother in the business with her, and had already, in 1793, married J. A. Streicher, a pianist from Stuttgart, and distinguished as a personal friend of Schiller. In 1802, the brother and sister dissolving partnership, Streicher began himself to take his full share of the work, and on Stein’s lines improved the Viennese instrument, so popular for many years and famous for its lightness of touch, which contributed to the special character of the Viennese school of pianoforte playing. Since 1862, when Steinway’s example caused a complete revolution in German and Austrian piano-making, the old wooden cheap grand piano has died out. We will quit the early German piano with an illustration (fig. 22) of an early square piano action in an instrument made by Johann Gottlob Wagner of Dresden in 1783. This interesting discovery of Mahillon’s introduces us to a rude imitation (in the principle) of Cristofori, and it appears to have no relation whatever to the clock-hammer motion seen in Frederici’s.

|

| Fig. 21.—Stein’s Action (the earliest so-called Viennese), 1780. |

|

| Fig. 22.—German Square Action, 1783. Piano by Wagner, Dresden. |

Burney, who lived through the period of the displacement of

the harpsichord by the pianoforte, is the only authority to

whom we can refer as to the introduction of the latter instrument

into England. He tells us,[24] in his gossiping way,

that the first hammer harpsichord that came to

England was made by an English monk at Rome,

The Piano-

forte in England.

a Father Wood, for an English gentleman, Samuel Crisp of

Chesington; the tone of this instrument was superior to that

produced by quills, with the added power of the shades of piano

and forte, so that, although the touch and mechanism were

so imperfect that nothing quick could be executed upon it, yet

in a slow movement like the “Dead March” in Saul it excited

wonder and delight. Fulke Greville afterwards bought this

instrument for 100 guineas, and it remained unique in England

for several years, until Plenius, the inventor of the lyrichord,

made a pianoforte in imitation of it. In this instrument the

touch was better, but the tone was inferior. We have no date

for Father Wood. Plenius produced his lyrichord, a sostenente

harpsichord, in 1745. When Mason imported a pianoforte in

1755, Fulke Greville’s could have been no longer unique. The

Italian origin of Father Wood’s piano points to a copy of Cristofori,

but the description of its capabilities in no way confirms this

supposition, unless we adopt the very possible theory that the

instrument had arrived out of order and there was on one in

London who could put it right, or would perhaps divine that it

was wrong. Burney further tells us that the arrival in London

of J. C. Bach in 1759 was the motive for several of the second-rate

harpsichord makers trying to make pianofortes, but with

no particular success. Of these Americus Backers (d. 1776),

Backers.

said to be a Dutchman, appears to have gained the

first place. He was afterwards the inventor of

the so-called English action, and as this action is based upon

Cristofori’s we may suppose he at first followed Silbermann in

copying the original inventor. There is an old play-bill of

Covent Garden in Messrs Broadwood’s possession dated the

16th of May 1767, which has the following announcement:—

“End of Act 1. Miss Brickler will sing a favourite song from Judith, accompanied by Mr Dibdin on a new instrument call’d Piano Forte.”

|

| Fig. 23.—Grand Piano Action, 1776. The “English” action of Americus Backers. |

The mind at once reverts to Backers as the probable maker of this novelty. Backers’s “Original Forte Piano” was played at the Thatched House in St James’s Street, London, in 1773. Ponsicchi has found a Backers grand piano at Pistoria, dated that year. It was Backers who produced the action continued in the direct principle by the firm of Broadwood, or with the reversed lever and hammer-butt introduced by the firm of Collard in 1835.

|

| Fig. 24.—Broadwood’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. English direct mechanism. |

The escapement lever is suggested by Cristofori’s first action, to which Backers has added a contrivance for regulating it by means of a button and screw. The check is from Cristofori’s second action. No more durable action has been constructed, and it has always been found equal, whether made in England or abroad, to the demands of the Broadwood; Stodart. most advanced virtuosi. John Broadwood and Robert Stodart were friends, Stodart having been Broadwood’s pupil; and they were the assistants of Backers in the installation of his invention. On his deathbed he commended it to Broadwood’s care, but Stodart appears to have been the first to advance it—Broadwood being probably held back by his partnership with his brother-in-law, the son of Shudi, in the harpsichord business. (The elder Shudi had died in 1773.) Stodart soon made a considerable reputation with his “grand” pianofortes, a designation he was the first to give them. In Stodart’s grand piano we first find an adaptation from the lyrichord of Plenius, of steel arches between the wrest-plank and belly-rail, bridging the gap up which the hammers rise, in itself an important cause of weakness. These are not found in any contemporary German instruments, but may have been part of Backers’s.

|

| Fig. 24.—Broadwood’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. English direct mechanism. |

|

| Fig. 25.—Collard’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. English action, with reversed hopper and contrivance for repetition added. |

Imitation of the harpsichord by “octaving” was at this time an object with piano makers. Zumpe’s small square piano had met with great success; he was soon enabled to retire, and his imitators, who were legion, continued his model with its hand stops for the dampers and sourdine, with little change but that which straightened the keys from the divergences inherited from the clavichord. John Broadwood took this domestic instrument first in hand to improve it, and in the year 1780 succeeded in entirely reconstructing it. He transferred the wrest-plank and pins from the right-hand side, as in the clavichord, to the back of the case, an improvement universally adopted after his patent, No. 1379 of 1783, expired. In this patent we first find the damper and piano pedals, since universally accepted, but at first in the grand pianofortes only. Zumpe’s action remaining with an altered damper, another inventor, John Geib, patented (No. 1571 of 1786) the hopper with two separate escapements, one of which soon became adopted in the grasshopper of the square piano, it is believed by Geib himself; and Petzold, a Paris maker, appears to have taken later to the escapement effected upon the key. We may mention here that the square piano was developed and continued in England until about the year 1860, when it went out of fashion.

To return to John Broadwood—having launched his reconstructed square piano, he next turned his attention to the grand piano to continue the improvement of it from the point where Backers had left it. The grand piano was in framing and resonance entirely on the harpsichord principle, the sound-board bridge being still continued in one undivided length. The strings, which were of brass wire in the bass, descended in notes of three unisons to the lowest note of the scale. Tension was left to chance, and a reasonable striking line or place for the hammers was not thought of. Theory requires that the notes of octaves should be multiples in the ratio of 1 to 2, by which, taking the treble clef C at one foot, the lowest F of the five-octave scale would require a vibrating length between the bridges of 12 ft. As only half this length could be conveniently afforded, we see at once a reason for the above-mentioned deficiencies. Only the three octaves of the treble, which had lengths practically ideal, could be tolerably adjusted. Then the striking-line, which should be at an eighth or not less than a ninth or tenth of the vibrating length, and had never been cared for in the harpsichord, was in the lowest two octaves out of all proportion, with corresponding disadvantage to the tone. John Broadwood did not venture alone upon the path towards rectifying these faults. He called in the aid of professed men of science—Tiberius Cavallo, who in 1788 published his calculations of the tension, and Dr Gray, of the British Museum. The problem was solved by dividing the sound-board bridge, the lower half of which was advanced to carry the bass strings, which were still of brass. The first attempts to equalize the tension and improve the striking-place were here set forth, to the great advantage of the instrument, which in its wooden construction might now be considered complete. The greatest pianists of that epoch, except Mozart and Beethoven, were assembled in London—Clementi, who first gave the pianoforte its own character, raising it from being a mere variety of the harpsichord, his pupils Cramer and for a time Hummel, later on John Field, and also the brilliant virtuosi Dussek and Steibelt. To please Dussek, Broadwood in 1791 carried his five-octave, F to F, keyboard, by adding keys upwards, to five and a half octaves, F to C. In 1794 the additional bass half octave to C, which Shudi had first introduced in his double harpsichords, was given to the piano. Steibelt, while in England, instituted the familiar signs for the employment of the pedals, which owes its charm to excitement of the imagination instigated by power over an acoustical phenomenon, the sympathetic vibration of the strings. In 1799 Clementi founded a pianoforte manufactory, to be subsequently developed and carried on by Messrs Collard.

The first square piano made in France is said to have been constructed in 1776 by Sebastian Erard, a young Alsatian. In 1786 he came to England and founded the London manufactory of harps and pianofortes bearing his name. That eminent mechanician and inventor is said to have at first adopted for his pianos the English models. Erard. However, in 1794 and 1801, as is shown by his patents, he was certainly engaged upon the elementary action described as appertaining to Gosselin’s piano, of probably German origin. In his long-continued labour of inventing and constructing a double escapement action, Erard appears to have sought to combine the English power of gradation of tone with the German lightness of touch. He took out his first patent for a “repetition” action in 1808, claiming for it “the power of giving repeated strokes without missing or failure, by very small angular motions of the key itself.” He did not, however, succeed in producing his famous repetition or double escapement action until 1821; it was then patented by his nephew Pierre Erard, who, when the patent expired in England in 1835, proved a loss from the difficulties of carrying out the invention, which induced the House of Lords to grant an extension of the patent.

Erard invented in 1808 an upward bearing to the wrest-plank bridge, by means of agraffes or studs of metal through holes in which the strings are made to pass, bearing against the upper side. The wooden bridge with down-bearing strings is clearly not in relation with upward-striking hammers, the tendency of which must be to raise the strings from the bridge, to the detriment of the tone. A long brass bridge on this principle was introduced by William Stodart in 1822. A pressure-bar bearing of later introduction is claimed for the French maker, Bord. The first to see the importance of iron sharing with wood (ultimately almost supplanting it) in pianoforte framing Hawkins. was a native of England and a civil engineer by profession, John Isaac Hawkins, known as the inventor of the ever-pointed pencil. He was living at Philadelphia, U.S.A., when he invented and first produced the familiar cottage pianoforte—“portable grand” as he then called it. He patented it in America, his father, Isaac Hawkins, taking out the patent for him in England in the same year, 1800. It will be observed that the illustration here given (fig. 28) represents a wreck; but a draughtsman’s restoration might be open to question.

|

| Fig. 27.—Steinway’s Grand Piano Action, 1884. The double escapement as in Erard’s, but with shortened balance and usual check. |

There had been upright grand pianos as well as upright harpsichords, the horizontal instrument being turned up upon its wider end and a keyboard and action adapted to it. William Southwell, an Irish piano-maker, had in 1798 tried a similar experiment with a square piano, to be repeated in later years by W. F. Collard of London; but Hawkins was the first to make a piano, or pianino, with the strings descending to the floor, the keyboard being raised, and this, although at the moment the chief, was not his only merit. He anticipated nearly every discovery that has since been introduced as novel. His instrument (fig. 28) is in a complete iron frame, independent of the case; and in this frame, strengthened by a system of iron resistance rods combined with an iron upper bridge, his sound-board is entirely suspended.

|

| Fig. 28.—Hawkins’s Portable Grand Piano, 1800. An upright instrument, the original of the modern cottage piano or pianino. In Messrs Broadwood’s museum and unrestored. |

An apparatus for tuning by mechanical screws regulates the tension of the strings, which are of equal length throughout. The action, in metal supports, anticipates Wornum’s in the checking, and still later ideas in a contrivance for repetition. This remarkable bundle of inventions was brought to London and exhibited by Hawkins himself; but the instrument being poor in the tone failed to bring him pecuniary reward or the credit he deserved. Southwell appears to have been one of the first to profit by Hawkins’s ideas by bringing out the high cabinet pianoforte, with hinged sticker action, in 1807. All that he could, however, patent in it was the simple damper action, turning on a pivot to relieve the dampers from the strings, which is still frequently used with such actions. The next steps for producing the lower or cottage upright piano were taken by Robert Wornum, who in 1811 produced a diagonally, and in 1813 a vertically, strung one. Wornum’s perfected crank action (fig. 29) was not complete until 1826, when it was patented for a cabinet piano; but it was not really introduced until three years later, when Wornum applied it to his little “piccolo.” The principle of this centred lever check action was introduced into Paris by Pleyel[25] and Pape, and thence into Germany and America.

|

| Fig. 29.—Wornum’s Upright Action, 1826. The original of the now universal crank action in upright pianos. |

It was not, however, from Hawkins’s invention that iron became introduced as essential to the structure of a pianoforte. This was due to William Allen, a young Scotsman in the employ of the Stodarts. He devised a metal system of framing intended primarily for compensation, but soon to become, Allen. in other hands, a framing for resistance. His idea was to meet the divergence in tuning caused in brass and iron strings by atmospheric changes by compensating tubes and plates of the same metals, guaranteeing their stability by a cross batoning of stout wooden bars and a metal bar across the wrest-plank. Allen, being simply a tuner, had not the full practical knowledge for carrying out the idea. He had to ally himself with Stodart’s foreman, Thom; and Allen and Thom patented the invention in January 1820. The firm of Stodart at once acquired the patent.

|

| Fig. 30.—Allen’s Compensating Grand Piano, 1820. The first complete metal framing system applied over the strings. |

We have now arrived at an important epoch in pianoforte construction—the abolition, at least in England and France, of the wooden construction in favour of a combined construction of iron and wood, the former material gradually asserting pre-eminence. Allen’s design is shown in fig. 30. The long bars shown in the diagram are really tubes fixed at one end only; those of iron lie over the iron or steel wire, while those of brass lie over the brass wire, the metal plates to which they are attached being in the same correspondence. At once a great advance was made in the possibility of using heavier strings than could be stretched before, without danger to the durability of the case and frame. The next step was in 1821, to a fixed iron string-plate, the invention of one of Broadwood’s workmen; Samuel Hervé, which was in the first instance applied to one of the square pianos of that firm. The great advantage in the fixed plate was a more even solid counterpoise to the drawing or tension of the strings and the abolition of their undue length behind the bridge, a reduction which Isaac Carter[26] had tried some years before, but unsuccessfully, to accomplish with a plate of wood. So generally was attention now given to improved methods of resistance that it has not been found possible to determine who first practically introduced those long iron or steel resistance bars which are so familiar a feature in modern grand pianos. They were experimented on as substitutes for the wooden bracing by Joseph Smith in 1798; but to James Broadwood belongs the credit of trying them first above the sound-board in the treble part of the scale as long ago as 1808, and again in 1818; he did not succeed, however, in fixing them properly. The introduction of fixed resistance bars is really due to observation of Allen’s compensating tubes, which were, at the same time, resisting. Sebastian and Pierre Erard seem to have been first in the field in 1823 with a complete system of nine resistance bars from treble to bass, with a simple mode of fastening them through the sound-board to the wooden beams beneath, but, although these bars appear in their patent of 1824, which chiefly concerned their repetition action, the Erards did not either in France or England claim them as of original invention, nor is there any string-plate combined with them in their patent. James Broadwood, by his patent of 1827, claimed the combination of string-plate and resistance bars, which was clearly the completion of the wood and metal instrument, differing from Allen’s in the nature of the resistance being fixed. Broadwood, however, left the brass bars out, but added a fourth bar in the middle to the three in the treble he had previously used. It must be borne in mind that it was the trebles that gave way in the old wooden construction before the tenor and bass of the instrument. But the weight of the stringing was always increasing, and a heavy close overspinning of the bass strings had become general. The resistance bars were increased to five, six, seven, eight and, as we have seen, even nine, according to the ideas of the different English and French makers who used them in their pursuit of stability.

|

| Fig. 31.—Broadwood’s Iron Grand Piano, 1884. Complete iron frame with diagonal resistance bar. |

The next important addition to the grand piano in order of time was the harmonic bar of Pierre Erard, introduced in 1838. This was a gun-metal bar of alternate pressing and drawing power by means of screws which were tapped into the wrest-plank immediately above the treble bearings, making that part of the instrument nearly immovable; this favoured the production of higher harmonics to the treble notes, recognized in what we commonly call “ring.” A similar bar, subsequently extended by Broadwood across the entire wrest-plank, was to prevent any tendency in the wrest-plank to rise, from the combined upward drawing of the strings. A method of fastening the strings on the string-plate depending upon friction, and thus dispensing with “eyes,” was a contribution of the Collards, who had retained James Stewart, a man of considerable inventive power, who had been in America with Chickering. This invention was introduced in 1827. Between 1847 and 1849 Mr Henry Fowler Broadwood, son of James, and grandson of John Broadwood, and also great-grandson of Shudi (Tschudi), invented a grand pianoforte to depend practically upon iron, in which, to avoid the conspicuous inequalities caused by the breaking of the scale with resistance bars, there should be no bar parallel to the strings except a bass bar, while another flanged resistance bar, as an entirely novel feature, crossed over the strings from the bass corner of the wrest-plank to a point upon the string-plate where the greatest accumulation of tension strain was found. Broadwood did not continue, without some compromise, this extreme renunciation of ordinary resistance means. After the Great Exhibition of 1851 he employed an ordinary straight bar in the middle of his concert grand scale, his smaller grands having frequently two such as well as the long bass bar. After 1862 he covered his wrest-plank with a thick plate of iron into which the tuning pins screw as well as into the wood beneath, thus avoiding the crushing of the wood by the constant pressure of the pin across the pull of the string, an ultimate source of danger to durability.

|

| Fig. 32.—Meyer’s Metal Frame for a Square Piano, 1833. In a single casting. |

The introduction of iron into pianoforte structure was differently and independently effected in America, the fundamental idea there being to use a single casting for the metal plate and bars, instead of forging or casting them in separate pieces. Alphaeus Babcock was the pioneer to this kind of metal construction. He also was bitten with the compensation notion, and had cast an iron ring for a square piano in 1825, which, although not a success, gave the clue to a single casting resistance framing, successfully accomplished by Conrad Meyer, in Philadelphia, in 1833, in a square piano which still exists, and was shown in the Paris Exhibition of 1878. Meyer’s idea was improved upon by Jonas Chickering (1797–1853) of Boston, who applied it to the grand piano as well as to the square, and brought the principle up to a high degree of perfection—establishing by it the independent construction of the American pianoforte.