1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Sculpture

SCULPTURE (Lat. sculptura, from sculpere, to carve, cognate with Gr. γλύφειν), a general term for the plastic art of carving, especially in stone and marble, but also in such materials as wood (see Wood-carving), ivory (see Ivory), metal (see Metal-work) and gems (see Gem).

The production of bronze statues by the cire perdue (anglice,

“lost wax”) process is described in the article Metal-work;

until (since its revival) recent times but little practised

in Europe outside of Paris, it has now invaded most

countries where fine casting Technical methods

of the

sculptor.is appreciated, and where sculptor.

naturalistic rendering is desired. There are signs,

however, of its being ousted for a certain class of handling by the “galvanoplastic” method—a system of copper deposit

by an electrical process—whereby “going over” the work

after it has been reproduced in metal is avoided.

For the execution of a marble statue the sculptor first models

a finished preliminary sketch on a small scale in clay or wax.

He then in the case of a life-size or colossal statue

has a sort of iron skeleton set up, with stout bars for

the arms and legs, fixed Clay

model.in the pose of the future figure.

This is called the “armature.” It is placed on a stand, called

a chassis, with a revolving top, so that the sculptor can easily

turn the whole model round and thus work with the light on any

side of it. Over this iron skeleton well-tempered modelling-clay

is laid and is modelled into shape by the help of wood and bone

tools; without the sustaining assistance of the ironwork a soft

clay figure, if more than a few inches high, would collapse with

its own weight and squeeze the lower part out of shape. While

the modelling is in progress it is necessary to keep the clay moist

and plastic by squirting water on to it with a sort of garden

syringe capped with a finely perforated rose. When the sculptor

is not at work the whole figure is kept wrapped up in damp

cloths. A modern improvement is to mix the modelling-clay,

not with water, but with stearin and glycerin; this, while

keeping the clay soft and plastic, has the great advantage of

not being wet, and so the sculptor avoids the chill and consequent

risk of rheumatism which follow from a constant manipulation

of wet clay. This method, however, has not been very extensively

adopted. When the clay model is finished it is cast in

plaster. A “piece-mould”[1] is formed by applying patches

of wet plaster of Paris all over the clay statue in such a way

that they can be removed piecemeal from the model, and then

be fitted together again, forming a complete hollow mould.

The inside is then rinsed out with plaster and water mixed to

the consistency of cream till a skin of plaster is formed all over

the inner surface of the mould, and thus a hollow cast is made

of the whole figure. The “piece-mould” is then taken to pieces

and the casting set free. If skilfully done by a good formatore

or moulder the plaster cast is a perfect facsimile of the original

clay, very slightly disfigured by a series of lines showing the

joints in the piece-mould, the sections of which cannot be made

to fit together with absolute precision. Many sculptors have

their clay model cast in plaster before the modelling is quite finished, as they prefer to put the finishing touches on the

plaster cast—good plaster being a very easy and pleasant

substance to work on.

The next stage is to copy the plaster model in marble. The

model is set on a large block called a “scale stone,” while the

marble for the future statue is set upon another similar block.

The plaster model is then covered with a series of marks, placed

on all the most salient parts of the body, and the front

of each “scale stone” is covered with another series of Pointing

the

marble.

points, exactly the same on both stones. An ingenious

instrument called a pointing machine, which has

arms ending in metal points or “needles” that move in ball-socket

joints, is placed between the model and the marble block. Two

of its arms are then applied to the model, one touching a point

on the scale stone while the other touches a mark on the figure.

The arms are fixed by screws in this position, and the machine

is then revolved to the marble block, and set with its lower needle

touching the corresponding point on the scale stone. The upper

needle, which is arranged to slide back on its own axis, cannot

reach the corresponding point on the statue because the marble

block is in the way; a hole is then drilled into the block at the

place and in the direction indicated by the needle, till the latter

can slide forward so as to reach a point sunk in the marble block

exactly corresponding to the point it touched on the plaster

mould. This process is repeated both on the model and on

the marble block till the latter is drilled with a number of holes,

the bottoms of which correspond in position to the number of

marks made on the surface of the model. A comparatively

unskilled scarpellino or “chisel-man” then sets to work and cuts

away the marble till he has reached the bottoms of all the holes,

beyond which he must not cut. The statue is thus roughly

blocked out, and a more skilled scarpellino begins

to work. Partly by eye and partly with the constant The scar-pellino.

help of the pointing machine, which is used to give

any required measurements, the workman almost completes

the marble statue, leaving only the finishing touches to be

done by the sculptor. In the opinion of many artists the use

of the mechanical pointing-machine is responsible in a great

measure for the loss of life and fire in much of modern

sculpture.

Among the ancient Greeks and Romans and in the medieval period it was the custom to give the nude parts of a marble statue a considerable degree of polish, which really suggests Polish on the somewhat glossy surface of the human skin very much better than the full loaf-sugar-like surface which Polish on marble. is left on the marble by most modern sculptors. This high polish still remains in parts of the pedimental figures from the Parthenon, where, at the back, they have been specially protected from the weather. The Hermes of the Vatican Belvidere is a remarkable instance of the preservation of this polish. Michelangelo carried the practice further still, and gave certain parts of some of his statues, such as the Moses, the highest possible polish in order to produce high lights just where he wanted them; the artistic legitimacy of this may perhaps be doubted, and in weak hands it might degenerate into mere trickery. It is, however, much to be desired that modern sculptors should to some extent at least adopt the classical practice, and by a slight but uniform polish remove the disagreeable crystalline grain from all the nude parts of the marble.

A rougher method of obtaining fixed points to measure from was occasionally employed by Michelangelo and earlier sculptors. They immersed the model in a tank of water, the water being gradually allowed to run out, and thus by its sinking level it gave a series of contour lines on any required number of planes. In some cases Michelangelo appears to have cut his statue out of the marble without previously making a model—a marvellous feat of skill.

In modelling bas-reliefs the modern sculptor usually applies the clay to a slab of slate on which the design is sketched; the slate forms the background of the figures, and thus keeps the relief absolutely true to one plane. This method is one of the causes of the dulness and want Relief sculpture. of spirit so conspicuous in most modern sculptured reliefs. In the best Greek examples there is no absolutely fixed plane surface for the backgrounds. In one place, to gain an effective shadow, the Greek sculptor would cut below the average surface; in another he would leave the ground at a higher plane, exactly as happened to suit each portion of his design. Other differences from the modern mechanical rules can easily be seen by a careful examination of the Parthenon frieze and other Greek reliefs. Though the word “bas-relief” is now often applied to reliefs of all degrees of projection from the ground, it should, of course, only be used for those in which the projection is slight; “basso,” “mezzo” and “alto rilievo” express three different degrees of salience. Very low relief is but little used by modern sculptors, mainly because it is much easier to obtain striking effects with the help of more projection. Donatello and other 1 5th-century Italian artists showed the most wonderful skill in their treatment of very low relief. One not altogether legitimate method of gaining effect was practised by some medieval sculptors: the relief itself was kept very low, but was “stilted” or projected from the ground, and then undercut all round the outline. A 15th-century tabernacle for the host in the Brera at Milan is a very beautiful example of this method, which as a rule is not pleasing in effect, since it looks rather as if the figures were cut out in cardboard and then stuck on (see Relief).

The practice of most modern sculptors is to do very little to the marble with their own hands; some, in fact, have never really learnt how to carve, and thus the finished statue is often very dull and lifeless in comparison with the clay model. Most of the great sculptorsSculptor’s assistants. of the middle ages left little or nothing to be done by an assistant; Michelangelo especially did the whole of the carving with his own hands, and when beginning on a block of marble attacked it with such vigorous strokes of the hammer that large pieces of marble flew about in every direction. But skill as a carver, though very desirable, is not absolutely necessary for a sculptor. If he casts in bronze by the cire perdue process he may produce the most perfect plastic works without touching anything harder than the modelling-wax. The sculptor in marble, however, must be able to carve a hard substance if he is to be master of his art. Unhappily some modern sculptors not only leave all manipulation of the marble to their workmen, but they also employ men to do their modelling, colloquially termed “ghosts,” the supposed sculptor supplying little or nothing but his sketch and his name to the work. The practice, however, is less common nowadays than formerly, owing mainly to one or two exposures which brought the matter sharply before the public. In some cases sculptors of ability who suffer under an excess of popularity are induced to employ aid of this kind on account of their undertaking more work than any one man could possibly accomplish—a state of things which is necessarily very hostile to the interests of true art. As a rule, however, the sculptor’s scarpellino, though he may and often does attain the highest skill as a Carver and can copy almost anything with wonderful fidelity, seldom develops into an original artist. The popular admiration for pieces of clever trickery in sculpture, such as the carving of the open meshes of a, fisherman’s net, or a chain with each link free and movable, or a veil over and half revealing the features of the face, would perhaps be diminished if it were known that such work as this is invariably done, not by the sculptor, but by the scarpellino. Unhappily at the present day there is, especially in England, little, appreciation of what is valuable in plastic art; there is probably no other civilized country where the State does so little to give practical support to the advancement of monumental and decorative sculpture on a large scale—the most important branch of the art—which it is hardly in the power of private persons to further.

It may here be well to say a few words on the technical methods

employed in the execution of medieval sculpture, which in the

main were very similar in England, France and Germany.

When bronze was used—in England as a rule only for

the effigies of royal persons or the richer nobles—the metalMedieval methods

and

materials.

was cast by the delicate cire perdue process, and the whole

surface of the figure was then thickly gilded. At Limoges

in France a large number of sepulchral effigies were produced, especially

between 1300 and 1400, and exported to distant places. These

were not cast, but were made of hammered (repoussé—q.v.) plates of

copper, nailed on a wooden core and richly decorated with champlevé

enamels in various bright colours. Westminster Abbey possesses a

fine example, executed about 1300, in the effigy of William of Valence

(d. 1296).[2] The ground on which the figure lies, the shield, the border

of the tunic, the pillow, and other parts are decorated with these

enamels very minutely treated. The rest of the copper was ilt, and

the helmet was surrounded with a coronet set with jewels, winch are

now missing. One royal effigy of later date at Westminster, that of

Henry V. (d. 1422), was formed of beaten silver fixed to an oak core,

with the exception of the head, which appears to have been cast.

The whole of the silver disappeared in the time of Henry VIII., and

nothing now remains but the rough wooden core; hence it is

doubtful whether the silver was decorated with enamel or not; it

was probably of English workmanship.

In most cases stone was used for all sorts of sculpture, being decorated in a very minute and elaborate way with gold, silver and colours applied over the whole surface. In order to give additional richness to this colouring the surface of the stone, often even in the case of external sculpture, was covered with a thin skin of gesso or fine plaster mixed with size; on this, while still soft, and over the drapery and other accessories, very delicate and minute patterns were stamped with wooden dies, and upon this the gold and colours were applied; thus the gaudiness and monotony of fiat smooth surfaces covered with gilding or bright colours were avoided.[3] In addition to this the borders of drapery and other arts of stone statues, were frequently ornamented with crystals and false jewels, or, in a more laborious way, with holes and sinkings filled with polished metallic foil, on which very minute patterns were painted in transparent varnish colours; the whole was then protected from the air by small pieces of transparent glass, carefully shaped to the right size and fixed over the foil in the cavity cut in the stone. It is difficult now to realize the extreme splendour of this gilt, painted and jewelled sculpture, as no perfect example exists, though in many cases traces remain of all these processes, and show that they were once very widely applied.[4] The architectural surroundings of the figures were treated in the same elaborate way. In the 14th century in England alabaster came into frequent use for monumental sculpture; it too was decorated with gold and colour, though in some cases the whole surface does not appear to have been so treated. In his wide use of coloured decoration, as in other respects, the medieval sculptor came far nearer to the ancient Greek than do any modern artists. Even the use of inlay of coloured glass was common at, Athens during the 5th century B.C.—as, for example, in the plait-band of some of the marble bases of the Erechtheum—and five or six centuries earlier at Tiryns and Mycenae,

Another material much used by medieval sculptors was wood, though, from its perishable nature, comparatively few early examples survive;[5] the best specimen is the figure of George de Cantelupe (d. 1273) in Abergavenny church. This was decorated with gesso reliefs, gilt and coloured in the same way as the stone. The tomb of Prince flohn of Eltham (d. 1334) at Westminster is a very fine example o the early use of alabaster, both for the recumbent effigy and also for a number of small figures of mourners all round the arcading of the tomb. These little figures, well preserved on the side which is protected by the screen, are of very great beauty and are executed with the most delicate minuteness some of the heads are equal to the best contemporary work of the son and pupils of Niccola Pisano. The tomb once had a high stone canopy of open work—arches, canopies and pinnacles—a class of architectural sculpture of which many extremely rich examples exist, as, for instance, the tomb of Edward II. at Gloucester, the de Spencer tomb at Tewkesbury, and, of rather later style, the tomb of Lady Eleanor Fitzalan de Percy at Beverley. This last is remarkable for the great richness and beauty of its sculptured foliage, which is of the finest Decorated period and stands unrivalled by any Continental example. The condition of this shrine (erected about 1335 to 1340) is almost perfect.

On technical methods, see (specially for the explanation of modelling, &c.) Edward Lantéri, Modelling (London, vol. 1, 1903, vol. 2, 1904, vol. 3, 1910), and Albert Toft, Modelling and Sculpture (London, 1910). These volumes give in detail every process and method of the sculptor’s craft with a fulness to be found in no other works of their class in the English language.

History

The following general sketch of the history of sculpture is confined mainly to that of the middle ages and modern times. The philosophy and aesthetics of the subject—the relation of sculpture to the other arts and the nature of its appeal to the emotions—are treated in the article Fine Arts. What is known as “classical” sculpture is dealt with under Greek Art and Roman Art; see also, for other allied aspects, China, Art; Japan, Art; Egypt, Art; Byzantine Art, and articles on Metal-work, Ivory, Wood-Carving, &c.; the article Architecture and allied articles (e.g. Capital); and the articles on the several individual artists.

In the 4th century A.D., under the rule of Constantine’s successors, the plastic arts in the Roman world reached the Bury lowest point of degradation to which they ever fell. Coarse in workmanship, intensely feeble in design, and utterly without expression or life, the paganEarly Christian. sculpture of that time is merely a dull and ignorant imitation of the work of previous centuries. The old faith was dead, and the art which had sprung from it died with it. In the same century a large amount of sculpture was produced by Christian workmen, which, though it reached no very high standard of merit, was at least far superior to the pagan work. Although it shows no increase of technical skill or knowledge of the human form, yet the mere fact that it was inspired and its subjects supplied by a real living, faith was quite sufficient to give it a vigour and a dramatic force, which raise it aesthetically far above the expiring efforts of paganism. Apart from ivories (see Ivory), a number of large marble sarcophagi are the chief existing specimens of this early Christian sculpture. In general design they are close copies of pagan tombs, and are richly decorated outside with reliefs. The subjects of these are usually scenes from the Old and New Testaments. From the former those subjects were selected which were supposed to have some typical reference to the life of Christ: the Meeting of Abraham and Melchisedec, the Sacrifice of Isaac, Daniel among the Lions, Jonah and the Whale, are those which most frequently occur. Among the New Testament scenes no representations occur of Christ’s sufferings;[6] the subjects chosen illustrate his power and beneficence: the Sermon on the Mount, the Triumphal Entry into Jerusalem, and many of his miracles are frequently repeated. The Vatican and Lateran museums are rich in examples of this sort. One of the finest in the former collection was taken from the crypt of the old basilica of St Peter; it contained the body of a certain Junius Bassus, and dates from the year 359.[7] Many other similar sarcophagi were made in the provinces of Rome, especially Gaul; and fine specimens exist in the museums of Arles, Marseilles and Aix; those found in Britain are of very inferior workmanship. Sculpture in the round, with its suggestion of idol worship which was offensive to the Christian spirit, was practically non-existent during this and the succeeding centuries, although there are a few notable exceptions, like the large bronze statue of St Peter[8] in the nave of St Peter’s in Rome, which is probably of 5th-century workmanship and has much of the repose, dignity and force of antique sculpture.

Italian plastic art in the 5th century continued to create in the spirit of the 4th century, especially reliefs in ivory (to a certain extent imitations of the later consular diptychs), which were used to decorate episcopal thrones or the bindings of MSS. of the Gospels. The so-called chair of St Peter, still preserved (though hidden from sight) in his great basilica, is the finest example of the former class; of less purely classical style, dating from about 550, is the ivory throne of Bishop Maximianus in Ravenna cathedral. Another very remarkable work of the 5th century is the series of small panel reliefs on the doors of S. Sabina on the Aventine Hill at Rome. There are scenes from Bible history carved in wood, and in them much of the old classic style survives.[9]

In the 6th century, under the Byzantine influence of Justinian, a new class of decorative sculpture was produced, especially at Ravenna. Subject reliefs do not often occur, but large slabs of marble, forming screens, altars, pulpits and the like, were ornamented in a very skilful and original way with low reliefs of graceful vine-plants, with peacocks and other birds drinking out of chalices, all treated in a very able and highly decorative manner. Byzantium, however, in the main, became the birthplace and seat of all the medieval arts soon after the transference thither of the headquarters of the empire (see Byzantine Art). It was natural that love of splendour and sumptuousness in the Eastern capital found expression in colour and richness of material rather than in monumental impressiveness. The school of sculpture which arose at Byzantium in the 5th or 6th century was therefore essentially decorative, and not monumental; and the skill of the sculptors was most successfully applied to work in metals and ivory, and the carving of foliage on capitals and bands of ornament, possessed of the very highest decorative power and executed with unrivalled spirit and vigour. The early Byzantine treatment of the acanthus or thistle, as seen in the capitals of S. Sophia at Constantinople, the Golden Gate at Jerusalem, and many other buildings in the East, has never since been surpassed in any purely decorative sculpture; and it is interesting to note how it grew out of the dull and lifeless ornamentation which covers the degraded Corinthian capital used so largely in Roman buildings of the time of Constantine and his sons.

Till about the 12th century, and in some places much later the art of Byzantium dominated that of the whole Christian world in a very remarkable way. The spread of this art was to a great extent due to the iconoclast riots which not only led to the destruction of images andInfluence of Byzantine art. works of art, but threatened the very life of the artists and craftsmen, who thereupon sought refuge in foreign countries, especially at the court of Charlemagne, and for several centuries determined the course of European art. From Russia to Ireland and from Norway to Spain any given work of art in one of the countries of Europe might almost equally well have been designed in any other. Few or no local characteristics or peculiarities can be detected, except of course in the methods of execution, and even these were wonderfully similar everywhere. The dogmatic unity of the Catholic Church and its great monastic system, with constant interchange of monkish craftsmen between one country and another, were the chief causes of this widespread monotony of style. An additional reason was the unrivalled technical skill of the early Byzantines, which made their city widely resorted to by the artist-craftsmen of all Europe—the great school for learning any branch of the arts.

The extensive use of the precious metals for the chief works of plastic art in this early period is one of the reasons why so few examples still remain—their great intrinsic value naturally causing their destruction. One of the most important existing examples, dating from the 8th century, is a series of colossal wall reliefs executed in hard stucco in the church of Cividale (Friuli) not far from Trieste. These represent rows of female saints bearing jewelled crosses, crowns and wreaths, and closely resembling in costume, attitude and arrangement the gift-bearing mosaic figures of Theodora and her ladies in S. Vitale at Ravenna. It is a striking instance of the almost petrified state of Byzantine art that so close a similarity should be possible between works executed at an interval of fully two hundred years. Some very interesting small plaques of ivory in the library of St Gall show a still later survival of early forms. The central relief is a figure of Christ in Majesty, closely resembling those in the colossal apse mosaic of S. Apollinare in Classe and other churches of Ravenna; while the figures below the Christ are survivals of a still older time, dating back from the best eras of classic art. A river-god is represented as an old man holding an urn, from which a stream issues, and a reclining female figure with an infant and a cornucopia is the old Roman Tellus or Earth-goddess with her ancient attributes.[10]

While the countries of the north could not altogether resist

the rising tide of Byzantinism, in Scandinavia, and to a great

extent in England, the autochthonous art was not

altogether obliterated during the early middle ages. In

England, during the Saxon period, when stone buildings

were rare and even large cathedrals were built of

Norse and Celtic influences

in England.

wood, the plastic arts were mostly confined to the use of

gold, silver, and gilt copper. The earliest existing specimens

of sculpture in stone are a number of tall churchyard crosses,

mostly in the northern provinces and apparently the work of

Scandinavian sculptors. One very remarkable example is a

tall monolithic cross, cut in sandstone, in the churchyard of

Gosforth in Cumberland. It is covered with rudely carved

reliefs, small in scale, which are of special interest as showing

a transitional state from the worship of Odin to that of Christ.

Some of the old Norse symbols and myths sculptured on it

occur modified and altered into a semi-Christian form. Though

rich in decorative effect and with a graceful outline, this sculptured

cross shows a very primitive state of artistic development,

as do the other crosses of this class in Cornwall, Ireland and

Scotland, which are mainly ornamented with those ingeniously

intricate patterns of interlacing knotwork designed so skilfully

by both the early Norse and the Celtic races.[11] They belong

to a class of art which is not Christian in its origin, though it

was afterwards largely used for Christian purposes, and so is

thoroughly national in style, quite free from the usual widespread

Byzantine influence. Of special interest from their early date—probably

the 11th century—are two large stone reliefs now in

Chichester cathedral, which are traditionally said to have come

from the pre-Norman church at Selsey. They are thoroughly

Byzantine in style, but evidently the work of some very ignorant

sculptor; they represent two scenes in the Raising of Lazarus;

the figures are stiff, attenuated and ugly, the pose very awkward,

and the drapery of exaggerated Byzantine character, with long

thin folds. To represent the eyes pieces of glass or coloured

enamel were inserted; the treatment of the hair in long ropelike

twists suggests a metal rather than a stone design.

The Romanesque period in art was essentially one of architectural activity. The spirit of the time did not encourage that individual thought which alone can produce a great development of sculpture and painting. Thus the plastic art of the 11th and 12th centuries, which was still entirely at the service and under the rule of Romanesque sculpture. the Church, was strictly confined to conventional symbols, ideas and forms. It is based, not on the study of nature, but on the late Roman reliefs. The treatment of the figures, though often rude and clumsy, and sometimes influenced by Byzantine stiffness, is on the whole dignified, solemn and serious, and bent upon the expression of the typical, and not of the individual. The tympana of the porches, the capitals of columns and the pulpits and choir-screens of the Romanesque churches, and, on a smaller scale, the ivory carvings for book-covers and portable miniature altars, provided the field for the Romanesque sculptors activity.

In Italy the strong current of hierarchal Byzantinism had never altogether supplanted the antique tradition, though the works based upon the latter, before Niccola Pisano revived for a short while the true spirit of the antique, are of almost barbaric rudeness, like the bronze gates of S. Zeno at Verona, and the stone-carving of The Last Supper on the pulpit of Italy. S. Ambrogio, in Milan. The real home of Romanesque sculpture was beyond the Alps, in Germany and France, and much of the work done in Italy during the 12th century was actually due to northern sculptors—as, for example, the very rude sculpture on the façade of S. Andrea at Pistoia, executed about 1186 by Gruamons and his brother Adeodatus,[12] or the relief by Benedetto Antelami for the pulpit of Parma cathedral of the year 1178. Unlike the sculpture of the Pisani and later artists, these early figures are thoroughly secondary to the architecture they are designed to decorate; they are evidently the work of men who were architects first and sculptors in a secondary degree. After the 13th century the reverse was usually the case, and, as at the west end of Orvieto cathedral, the sculptured decorations are treated as being of primary importance—not that the Italian sculptor-architect ever allowed his statues or reliefs to weaken or damage their architectural surroundings, as is unfortunately the case with much modern sculpture. In southern Italy, during the 13th century, there existed a school of sculpture resembling that of France, owing probably to the Norman occupation. The pulpit in the cathedral of Ravello, executed by Nicolo di Bartolommeo di Foggia in 1272, is an important work of this class; it is enriched with very noble sculpture, especially a large female head crowned with a richly foliated Coronet, and combining lifelike vigour with largeness of style in a very remarkable way. The bronze doors at Monreale (by Barisanus of Trani), Pisa and elsewhere are among the chief works of plastic art in Italy during the 12th century. The history of Italian sculpture of the best period is given to a great extent in the separate articles on the Pisani and other Italian artists. Here it suffices to say that sculpture never became as completely subservient to architecture, as it did in the north, and that with Giovanni Pisano the almost classic repose and dignity of his father Niccola’s style gave way—probably owing to northern influences—to an increased sense of life and freedom and dramatic expression. Niccola stands at the close of the Romanesque, and Giovanni on the threshold of the Gothic period. During the 13th century Rome and the central provinces of Italy produced very few sculptors of ability, almost the only men of note being the Cosmati.

The power acquired by Germany under the Saxon emperors; upon whom had descended the mantle of the Roman Caesars was the chief reason that led to the great development of Romanesque art in Germany. It is true that, in the 11th century, Byzantine influences stifled the spontaneous naïveté of the earlier work; but about the German bronze work. end of the 12th century a new free and vital art arose, based upon a better understanding of the antique, and fostered by the rise of feudalism and the prosperity of the cities. Next in importance to the numerous examples of German Romanesque ivory carvings are the works in bronze, in the technique of which the German craftsmen of the pre-Gothic period stand unrivalled. This is seen in the bronze pillar reliefs and other works, notably the bronze gates of Hildesheim Cathedral, produced by Bishop Bernward (d. 1022) after his visit to Rome. Hildesheim, Cologne and the whole of the Rhine provinces were the most active seats of German sculpture, especially in metal, till the rzth century. Many remarkable pieces of bronze sculpture were produced at the end of that period, of which several specimens exist. The bronze font at Liége, with figure-subjects in relief of various baptismal scenes from the New Testament, by Lambert Patras of Dinant, cast about 1112, is a work of most wonderful beauty and perfection for its time; other fonts in Osnabrück, by Master Gerhard, and Hildesheim cathedrals are surrounded by spirited reliefs, fine in conception, but inferior in beauty to those on the Liége font. Fine bronze candelabra exist in the abbey church of Combourg and at Aix-la-Chapelle, the latter of about 1165. Merseburg cathedral has a strange realistic sepulchral figure of Rudolf of Swabia, executed about 1100; and at Magdeburg is a fine effigy, also in bronze, of Bishop Frederick (d. 1152), treated in a more graceful way. The last figure has a peculiarity which is not uncommon in the older bronze reliefs of Germany: the body is treated as a relief, while the head sticks out and is quite detached from the ground in a very awkward way. One of the finest plastic works of this century is the choir screen of Hildesheim cathedral, executed in hard stucco, one rich with gold and colours; on its lower part is a series of large reliefs of saints modelled with almost classical breadth and nobility, with drapery of especial excellence. In the 13th century German sculpture had made considerable artistic progress, but it did not reach the high standard of France. One of the best examples of the transition period from German Romanesque to Gothic is the “golden gate” of Freiburg cathedral, with sculptured figures on the jambs after the French fashion. The statues of the apostles on the nave pillars, and especially one of the Madonna at the east end (1260–1270), possess great beauty and sculpturesque breadth. Of the same period, and kindred in style and feeling, are the reliefs on the eastern choir-screen in Bamberg cathedral.

France is comparatively poor in characteristic examples of Romanesque sculpture, as the time of the greatest activity coincides with the beginnings of the Gothic style, so that in many cases, as for instance on the porches of Bourges and Chartres cathedrals, Romanesque and Gothic features occur side by side and make it impossible to establish a France. clear demarcation between the two. Among the most important Romanesque monuments of the early 12th century are the sculptures on the porch of the abbey church of Conques, representing the Last Judgment; the somewhat barbaric tympanum of Autun cathedral (c. 1130); and that of the church of Moissac.

During the 12th and 13th centuries the prodigious activity of the cathedral builders of France and their rivalry to outshine each other in the richness of the sculptured decorations, led to the glorious development that culminated in the full flower of Gothic art. The façades of large cathedrals were completely covered with sculptured reliefs and thick-set rows of statues in niches. The whole of the front was frequently one huge composition of statuary, with only sufficient purely architectural work to form a background and frame for the sculptured figures. A west end treated like that of Wells cathedral, which is almost unique in England, is not uncommon in France. Even the shafts of the doorways and other architectural accessories were covered with minute sculptured decoration,—the motives of which were often, especially during the 12th century, obviously derived from the metal-work of shrines and reliquaries studded with rows of jewels. The west façade of Poitiers cathedral is one of the richest examples; it has large surfaces covered with foliated carving and rows of colossal statues, both seated and standing, reaching high up the front of the church. Of the same century (the 12th), but rather later in date, is the very noble sculpture on the three western doors of Chartres cathedral, with fine tympanum reliefs and colossal statues (all once covered with painting and gold) attached to the jamb-shafts of the openings. These latter figures, with their exaggerated height and the long straight folds of their drapery, are designed with great skill to assist and not to break the main upward lines of the doorways. The sculptors have willingly sacrificed the beauty and proportion of each separate statue for the sake of the architectonic effect of the whole façade. The heads, however, are full of nobility, beauty, and even grace, especially those that are softened by the addition of long wavy curls, which give relief to the general stiffness of the form. The sculptured doors of the north and south aisles of Bourges cathedral are fine examples of the end of the 12th century, and so were the west doors of Notre Dame in Paris till they were hopelessly injured by “restoration.” The early sculpture at Bourges is specially interesting from the existence in many parts of its original coloured decoration.

Romanesque sculpture in England, during the Norman period, was of a very rude sort and generally used for the tympanum reliefs over the doors of churches. Christ in Majesty, the Harrowing of Hell and St George and the Dragon occur very frequently. Reliefs of the zodiacal signs were a common decoration of the Norman period in England. richly sculptured arches of the 12th century, and are frequently carved with much power. The later Norman sculptured ornaments are very rich and spirited, though the treatment of the human figure is still very weak.[13]

The best-preserved examples of monumental sculpture of the 12th century are a number of effigies of knights-templars in the round Temple church in London.[14] They are laboriously cut in hard Purbeck marble, and much resemble bronze in their treatment; the faces are clumsy, and the whole figures stiff and heavy in modelling; but they are valuable examples of the military costume of the time, the armour being purely chain-mail. Another effigy in the same church cut in stone, once decorated with painting, is a much finer piece of sculpture of about a century later. The head, treated in an ideal way with wavy curls, has much simple beauty, showing a great artistic advance. Another of the most remarkable effigies of this period is that of Robert, duke of Normandy (d. 1134), in Gloucester cathedral, carved with much spirit in oak, and decorated with painting. The realistic trait of the crossed legs, which occurs in many of these effigies, heralds the near advent of Gothic art. Most rapid progress in all the arts, especially that of sculpture, was made in England in the second half of the 13th and the beginning of the 14th century, largely under the patronage of Henry III., who employed and handsomely rewarded a large number of English artists, and also imported others from Italy and Spain, though these foreigners took only a secondary position among the painters and sculptors of England. The end of the 13th century was in fact the culminating period of English art, and at this time a very high degree of excellence was reached by purely national means, quite equalling and even surpassing the general average of art on the Continent, except perhaps in France. Even Niccola Pisano could not have surpassed the beauty and technical excellence of the two bronze effigies in Westminster Abbey modelled and cast by William Torell, a goldsmith and citizen of London, shortly before the year 1300. These are on the tombs of Henry III. and Queen Eleanor (wife of Edward I.), and, though the tomb itself of the former is an Italian work of the Cosmati school, there is no trace of foreign influence in the figures. At this time portrait effigies had not come into general use, and both figures are treated in an ideal way.[15] The crowned head of Henry III., with noble well-modelled features and crisp wavy curls, resembles the conventional royal head on English coins of this and the following century, while the head of Eleanor is of remarkable, almost classic, beauty, and of great interest as showing the ideal type of the 13th century. In both cases the drapery is well conceived in broad sculpturesque folds, graceful and yet simple in treatment. The casting of these figures, which was effected by the cire perdue process, is technically very perfect. The gold employed for the gilding was got from Lucca in the shape of the current Horins of that time, which were famed for their purity. Torell was highly paid for this, as well as for two other bronze statues of Queen Eleanor, probably of the same design.

Although the difference between fully developed Gothic sculpture and Romanesque sculpture is almost as clearly marked as the difference between Gothic and Romanesque architecture— indeed, the evolution of the two arts proceeded in parallel stages—the change from the earlier to the later style is so gradual and almost imperceptible, that it is all but impossible to follow it step by step, and to illustrate it by examples. What distinguishes the Gothic from the Romanesque in sculpture is the striving to achieve individual in the place of typical expression. This striving is as apparent in the more flexible and emotional treatment of the human figure, as it is in the substitution of naturalistic plant and animal forms for the more conventional ornamentation of the earlier centuries. Statuesque architectonic dignity and calmness are replaced by slender grace and soulful expression. The drapery, instead of being arranged in heavy folds, clings to the body and accentuates rather than conceals the form. At the same time, the subjects treated by the Gothic sculptor do not depart to any marked degree from those which fell to the task of the Romanesque workers, though they are brought more within the range of human emotions.

It is only natural that in France, which was the birthplace of Gothic architecture, the sister art of sculpture should have attained its earliest and most striking development. During the 13th century, the imagiers, or stone sculptors, worked hand in hand with the great cathedral builders. This century may indeed Gothic sculp-ture in France.be called the golden age of Gothic sculpture.

While still keeping its early dignity and subordination to its architectural setting, the sculpture reached a very high degree of graceful inish and even sensuous beauty. Nothing could surpass the loveliness of the angel statues round the Sainte Chapelle in Paris, and even the earlier work on the façade of Laon cathedral is full of grace and delicacy. Amiens cathedral is especially rich in sculpture of this date,—as, for example, the noble and majestic statues of Christ and the Apostles at the west end; the sculpture on the south transept of about 1260–1270, of more developed style, is remarkable for dignity combined with soft beauty.[16] The noble row of kings on the west end of Notre Dame at Paris has, like the earlier sculpture, been ruined by “restoration,” which has robbed the statues of both their spirit and their vigour. To the latter years of the 13th century belong the magnificent series of statues and reliefs round the three great western doorways of the same church, among which are no fewer than thirty-four life-sized figures. On the whole, the single statues throughout this period are finer than the reliefs with many figures. Some of the statues of the Virgin and Child are of extraordinary beauty, in spite of their being often treated with a certain mannerism—a curved pose of the body, which appears to have been copied from ivory statuettes, in which the figure followed the curve of the elephant's tusk. The north transept at Rheims is no less rich: the central statue of Christ is a work of much grace and nobility of form; and some nude figures—for example, that of St Sebastian show a knowledge of the human body which was very unusual at that early date. Many of these Reims statues, like those by Torell at Westminster, are quite equal to the best work of Niccola Pisano. The abbey church of St Denis possesses the largest collection of French 13th-century monumental effigies, a large number of which, with supposed portraits of the early kings, were made during the rebuilding of the church in 1264; some of them appear to be “archaistic” copies of older contemporary statues.[17]

In the 14th century French sculpture began to decline, though much beautiful plastic work was still produced. Some of the reliefs on the choir screen of Notre Dame at Paris belong to this period, as does also much fine sculpture on the transepts of Rouen cathedral and the west end of Lyons. At the end of this century an able sculptor from the Netherlands, Claus Sluter (who followed the tradition of the 14th-century school of Tournai, which is marked by the exquisite study of the details of nature and led to the brilliant development of Flemish realism), executed much fine work, especially at Dijon, under the patronage of Philip the Bold, for whose newly founded Carthusian monastery in 1399 he sculptured the great “Moses fountain” in the cloister, with six life-sized statues of prophets in stone, painted and gilt in the usual medieval fashion. Not long before his death in 1411 Sluter completed a very magnificent altar tomb for Philip the Bold, now in the museum at Dijon. It is of white marble, surrounded with arcading, which contains about forty small alabaster figures representing mourners of all classes, executed with much dramatic power. The recumbent portrait effigy of Philip in his ducal mantle with folded hands is a work of great power and delicacy of treatment.[18]

Whilst in France there was a distinct slackening in building activity in the 14th century, which led to a corresponding decline in sculpture, Germany experienced a reawakening of artistic creative energy and power. That the style had taken root on German soil in the preceding century, is proved by the fresh, mobile German 13th-century Gothic sculpture. treatment of the statues on the south porch of the east façade of Bamberg cathedral, and even more by the equestrian statue of Conrad III. in the market-place at Bamberg, which supported by a foliated corbel, exhibits startling vigour and originality, and is designed with wonderful largeness of effect, though small in scale. The statues of Henry the Lion and Queen Matilda at Brunswick, of about the same period, are of the highest beauty and dignity of expression. Strassburg cathedral, though sadly damaged by restoration, still possesses a large quantity of the finest sculpture of the 13th century. One tympanum relief of the Death of the Virgin, surrounded by the sorrowing Apostles, is a work of the very highest beauty, worthy to rank with the best Italian sculpture of even a later period. Of its class nothing can surpass the purely decorative carving at Strassburg, with varied realistic foliage studied from nature, evidently with the keenest interest and enjoyment.

But such works were only isolated manifestations of German artistic genius, until, in the next century, sculpture rose to new and splendid life, though it found expression not so much in the composition of extensive groups, as in the neighbouring France, but in the carving of isolated figures of rare and subtle beauty.

Nuremberg is rich in good sculpture of the 14th century. The church of St Sebald, the Frauenkirche, and the west façade of St Lawrence are lavishly decorated with reliefs and statues, very rich in effect, but showing the germs of that mannerism which grew so strong in Germany during the 15th century. Of special beauty are the statuettes which adorn the “beautiful fountain,” which was formerly erroneously attributed to the probably mythical sculptor Sebald Schonhofer, and is decorated with gold and colour by the painter Rudolf.[19] Of considerable importance are the statues of Christ, the Virgin, and the Apostles on the piers in the choir of Cologne cathedral, which were completed after 1350. They are particularly notable for their admirable polychromatic treatment. The reliefs on the high altar, which are of later date, are wrought in white marble on a background of black marble. Augsburg produced several sculptors of ability about this time; the museum possesses some very noble wooden statues of this school, large in scale and dignified in treatment. On the exterior of the choir of the church of Marienburg castle is a very remarkable colossal figure of the Virgin of about 1340–1350. Like the Hildesheim choir screen, it is made of hard stucco and is decorated with glass mosaics. The equestrian bronze group of St George and the Dragon in the market-place at Prague is excellent in workmanship and full of vigour, though much wanting dignity of style. Another fine work in bronze of about the same date is the effigy of Archbishop Conrad (d. 1261) in Cologne cathedral, executed many years after his death. The portrait appeals truthful and the whole figure is noble in style. The military effigies of this time in Germany as elsewhere were almost unavoidably stiff and lifeless from the necessity of representing them in plate armour. The ecclesiastical chasuble, in which priestly efligies nearly always appear, is also a thoroughly unsculpturesque form of drapery, both from its awkward shape and its absence of folds. The Günther of Schwarzburg (d. 1349) in Frankfort cathedral is a characteristic example of these sepulchral effigies in slight relief.

In England, much of the fine 13th-century sculpture was used to decorate the façades of churches, though, on the whole, English cathedral architecture did not offer such great opportunities to the imagier as did that of France. A notable exception is Wells cathedral, the west end of which, dating from about the middle of the century, Architectural sculpture in England. is covered with more than 600 figures in the round or in relief, arranged in tiers, and of varying sizes. The tympana of the doorways are filled with reliefs, and above them stand rows of colossal statues of kings and queens, bishops and knights, and saints both male and female, all treated very skilfully with nobly arranged drapery, and graceful heads designed in a thoroughly architectonic way, with due regard to the main lines of the building they are meant to decorate. In this respect the early medieval sculptor inherited one of the great merits of the Greeks of the best period: his figures or reliefs form an essential part of the design of the building to which they are affixed, and are treated in a subordinate manner to their architectural surroundings-very different from most of the sculpture on modern buildings, which frequently looks as if it had been stuck up as an afterthought, and frequently by its violent and incongruous lines is rather an impertinent excrescence than an ornament.[20] Peterborough, Lichfield and Salisbury cathedrals have hue examples of the sculpture of the 13th century: in the chapter-house of the last the spandrels of the wall-arcade are filled with sixty reliefs of subjects from Bible history, all treated with much grace and refinement. To the end of the same century belong the celebrated reliefs of angels in the spandrels of the choir arches at Lincoln, carved in a large massive way with great strength of decorative effect. Other fine reliefs of angels, executed about 1260, exist in the transepts of Westminster Abbey; being high from the ground, they are broadly treated without any high finish in the details.[21]

Purely decorative carving in stone reached its highest point of excellence about the middle of the 14th century-rather later, that is, than the best period of figure sculpture. Wood-carving (q.v.), on the other hand, reached its artistic climax a full century later under the influence of the fully developed Perpendicular style.

The most important effigies of the 14th century are those in gilt bronze of Edward III. (d. 1377) and of Richard II. and his queen (made in 1395), all at Westminster. They are all portraits, but are decidedly inferior to the earlier work of William Torell. The effigies of Richard II. and Anne of Bohemia were the work of Nicolas Broker and Godfred Prest, goldsmith citizens of London. Another fine bronze effigy is at Canterbury on the tomb of the Black Prince (d. 1376); though well cast and with carefully modelled armour, it is treated in a somewhat dull and conventional way. The recumbent stone figure of Lady Arundel, with two angels at her head, in Chichester cathedral is remarkable for its calm peaceful pose and the beauty of the drapery. Among the most perfect works of this description is the alabaster tomb of Ralph Nevill, first earl of Westmorland, with figures of himself and his two wives, in Staindrop church, county Durham (1426), removed, 1908, from a dark corner of the church into full light, a few feet away, where its beauty may now be examined. A very fine but more realistic work is the tomb figure of William of Wykeham (d. 1404) in the cathedral at Winchester. The cathedrals at Rochester, Lichfield, York, Lincoln, Exeter and many other ecclesiastical buildings in England are rich in examples of 14th-century sculpture, used occasionally with great profusion and richness of effect, but treated in strict subordination to the architectural background.

The finest piece of bronze sculpture of the 15th-century is the effigy of Richard Beauchamp (d. 1439) in his family chapel at Warwick—a noble portrait figure, richly decorated with engraved ornaments. The modelling and casting were done by William Austen of London, and the gilding and engraving by a Netherlands goldsmith who had settled in London, named Bartholomew Lambespring, assisted by several other skilful artists.

The first Spanish sculptor of real eminence who need be considered is Aparicio, who lived and worked in the 11th century. His shrine of St Millan, executed to the order of Don Sancho the Great is in the monastery of Yuso, and is a composition excellent, in its way, in design, grace and proportion. In the early medieval period the sculpture of northern Spain. Spain was much influenced by contemporary art in France. From the 12th to the 14th century many French architects and sculptors visited and worked in Spain. The cathedral of Santiago de Compostella possesses one of the grandest existing specimens in the world of late 12th-century architectonic sculpture; this, though the work of a native artist, Mastei Mateo,[22] is thoroughly French in style; as recorded by an inscription on the front, it was completed in 1188. The whole of the western portal with its three doorways is covered with statues and reliefs, all richly decorated with colour, part of which still remains. Round the central arch are figures of the twenty-four elders, and in the tympanum a very noble relief of Christ in Majesty between Saints and Angels. As at Chartres, the jamb shafts of the doorways are decorated with standing statues of saints—St James the elder, the patron of the church, being attached to the central pillar. These noble figures, though treated in a somewhat rigid manner, are thoroughly subordinate to the main lines of the building. Their heads, with pointed beards and a fixed mechanical smile, together with the stiff drapery arranged in long narrow folds, recall the Aeginetan pediment sculpture of about 500 B.c. This appears strange at first sight, but the fact is that the 'works of the early Greek and the medieval Spaniard were both produced at a somewhat similar stage in two far distant periods of artistic development. In both cases plastic art was freeing itself from the bonds of -a. hieratic archaism, and had reached one of the last steps in a development which in the one case culminated in the perfection of the Phidian age, and in the other led to the exquisitely beautiful yet simple and reserved art of the end of the 13th and early part of the 14th century-the golden age of sculpture in France and England. In the cathedral of Tarragona are nine statues, in stone, executed by Bartolomé in 1278 for the gate.

In the 14th century the silversmiths of Spain produced many works of sculpture of great size and technical power. One of the finest, by a Valencian called Peter Bernec, is the great silver retable at Gerona cathedral. It is divided into three tiers of statuettes and reliefs, richly framed in canopied niches, all of silver, partly cast and partly hammered.

In the 15th century an infusion of German influence was mixed with that of France, as may be seen in the very rich sculptural decorations which adorn the main door of Salamanca cathedral, the façade of S. Juan at Valladolid, and the church and cloisters of S. Juan de los Reyes at Toledo, perhaps the most gorgeous examples of architectural sculpture in the world. These were executed between 1418 and 1425 by a group of clever sculptors, among whom A. and F. Diaz, A. F. de Sahagun, A. Rodriguez and A. Gonzales were perhaps the chief. The marble altar-piece of the grand altar at Tarragona was begun

|

|

| (Photo, Brogi.) | (Photo, Anderson.) |

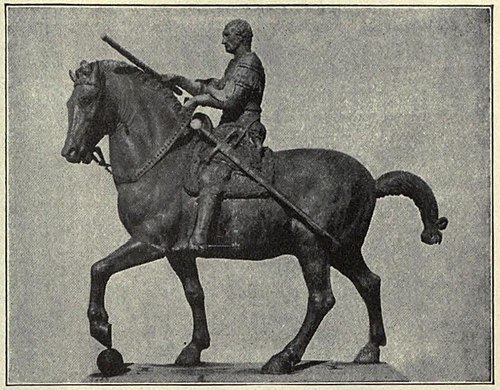

| JACOPO DELLA QUERCIA—Tomb, Ilaria del Carretto, Lucca. | DONATELLO—Equestrian Statue, General Gattamelata, Padua. |

|

|

| (Photo, Giraudon.) | (Photo, Löwy.) |

| JEAN GOUJON—Diane de Poitiers (as Huntress), in the Louvre. | CANOVA—Colossal Marble Group of Theseus and Centaur, Vienna. |

|

|

| (Photo, Giraudon.) | (Photo, Giraudon.) |

| HOUDON—Voltaire (Théàtre Français, Paris). | COYSEVOX—Bust of himself, in the Louvre. |

by P. Juan in 1426 and completed by G. De La Mota. The carved foliage of this period is of especial beauty and spirited execution; realistic forms of plant-growth are mingled with other more conventional foliage in the most masterly manner. The very noble bronze monument of Archdeacon Pelayo (d. 1490) in Burgos cathedral was probably the work of Simon of Cologne, who was also architect of the Certosa at Miraflores, 2 m. from Burgos. The church of this monastery contains two of the most magnificently rich monuments in the world, especially the altar-tomb of King John II. and his queen by Gil de Siloe—a perfect marvel of rich alabaster canopy-work and intricate under-cutting. The effigies have little merit. From the 16th century onwards wood was a favourite material with Spanish sculptors, who employed it for devotional and historical groups realistically treated, such as the “Scene from Taking of Granada” by El Maestre Rodrigo, and even for portraiture, as in the Bust of Turiano by Alonzo Berruguete (1480–1561).

During the 14th century Florence and the neighbouring

cities were the chief centres of Italian sculpture, and there

numerous sculptors of successively increasing artistic

power lived and worked, till in the 15th century the

city had become the aesthetic capital of the world.Gothic sculpture

in Italy.

But the Gothic sculptor’s activity was by no means

confined to Tuscany, for in northern Italy various schools

of sculpture existed in the 14th century, especially at Verona

and Venice, whose art differed widely from the contemporary

art of Tuscany; but Milan and Pavia, on the other hand, possessed

sculptors who followed closely the style of the Pisani. The chief

examples of the latter class are the magnificent shrine of St

Augustine in the cathedral of Pavia, dated 1362, and the somewhat

similar shrine of Peter the Martyr (1339), by Balduccio

of Pisa, in the church of S. Eustorgio at Milan, both of white

marble, decorated in the most lavish way with statuettes and

subject reliefs. Many other fine pieces of the Pisan school exist

in Milan. The well-known tombs of the Scaliger family at

Verona show a more native style of design, and in general form,

though not in detail, suggest the influence of trans alpine Gothic.

In Venice the northern and almost French character of much

of the early 15th-century sculpture is more strongly marked,

especially in the noble figures in high relief which decorate

the lower story and angles of the doge’s palace;[23] these are.

mostly the work of a Venetian named Bartolomeo Bon. A

magnificent marble tympanum relief by Bon can be seen at the

Victoria and Albert Museum; it has a noble colossal figure

of the Madonna, who shelters under her mantle a number of

kneeling worshippers; the background is enriched with foliage

and heads, forming a “lesse tree,” designed with great decorative

skill. The cathedral of Como, built at the very end of the 15th

century, is decorated with good sculpture of almost Gothic

style, but on the whole rather dull and mechanical in detail,

like much of the sculpture in the extreme north of Italy. A

large quantity of rich sculpture was produced in Naples during

the 14th century, but of no great merit either in design or in

execution. The lofty monument of King Robert (1350), behind

the high altar of S. Chiara, and other tombs in the same church

are the most conspicuous works of this period. The extraordinary

poverty in the production of sculpture in Rome during the 14th

century was remarkable. The clumsy effigies at the north-east

of S. Maria in Trastevere are striking examples of the degradation

of the plastic art there about the year 1400; and it was not

till nearly the middle of the century that the arrival of able

Florentine sculptors, such as Filarete, Mino da Fiesole, and the

Pollaiuoli, initiated a brilliant era of artistic activity, which,

however, for about a century continued to depend on the presence

of sculptors from Tuscany and other northern provinces. It

was not, in fact, till the period of full decadence had begun that

Rome itself produced any notable artists.

In Florence, the centre of artistic activity during the 15th as well as the 14th century, Giotto not only inaugurated the modern era of painting, but in his relief sculpture, and more particularly by the influence he exercised upon Andrea Pisano, carried the art of sculpture beyond the point where it had been left by Giovanni Pisano. In Andrea we find something of Niccola’s classic dignity grafted on to Giovanni’s close observation of nature. His greatest works are the bronze south gate of the Baptistery, and some of the reliefs on Giotto’s Campanile. The last great master of the Gothic period is Andrea di Cione, better known as Orcagna (1308? to 1368), who, like Giotto, achieved fame in the three sister arts of painting, sculpture and architecture. His wonderful tabernacle at Or San Michele is a noble testimony to his efficiency in the three arts and to his early training as a goldsmith. Very beautiful sepulchral effigies in low relief were produced in many parts of Italy, especially at Florence. The tomb of Lorenzo Acciaioli, in the Certosa near Florence, is a fine example of about the year 1400, which has absurdly been attributed to Donatello. The similarity between the plastic arts of Athens in the 5th or 4th century B.C. and of Florence in the 15th century is not one of analogy only. Though free from any touch of copyism, there are many points in the works of such men as Donatello, Luca della Robbia, and Antonio Pisano which strongly recall the sculpture of ancient Greece, and suggest that, if a sculptor of the later Fhidian school had been surrounded by the same types of face and costume as those among which the Italians lived, he would have produced plastic works closely resembling those of the great Florentine masters. Lorenzo Ghiberti may be called the first of the great sculptors of the Renaissance. But between him and Orcagna stands another master, the Sienese, Jacopo della Quercia[24] (1371–1438) who, although in some minor traits connected with the Gothic school, heralds at this early date the boldest and most vigorous and original achievements of two generations hence. Indeed, Jacopo, whose chief works are the Fonte Gaja at Siena (now reconstructed) and the reliefs on the gate of S. Petronio at Bologna, stands in his strong muscular treatment of the human figure nearer to Michelangelo than to his Gothic precursors and contemporaries. Contemporaneously with Ghiberti, the sculptor of the world-famed baptistery gates, and with Donatello, and to a certain extent influenced by them, worked some men who, like Ciuffagni, were still essentially Gothic in their style, or, like Nanni di Banco, retained unmistakable traces of the earlier manner. Luca della Robbia, the founder of a whole dynasty of sculptors in glazed terra-cotta, with his classic purity of style and sweetness of expression, came next in order. Unsensual beauty elevated by religious spirit was attained in the highest degree by Mino da Fiesole, the two Rossellini, Benedetto da Maiano, Desiderio da Settignano and other sculptors more or less directly influenced by Donatello. Through them the tomb monument received the definite form which it retained throughout the Renaissance period. Two of the noblest equestrian statues the world has probably ever seen are the Gattamelata statue at Padua by Donatello and the statue of Colleoni at Venice by Verrocchio and Leopardi. A third, which was probably of equal beauty, was modelled in clay by Leonardo da Vinci, but it no longer exists. Among other sculptors who flourished in Italy about the middle of the 15th century, are the Lucchese Matteo Civitali; Agostino di Duccio (1418–c. 1481), whose principal works are to be found at Rimini and Perugia; the bronze-worker Bertoldo di Giovanni (1420–1491); Antonio del Pollaiuolo, the author of the tombs of popes Sixtus IV. and Innocent VIII. at St Peter’s in Rome; and Francesco Laurana (1424–1501?), a Dalmatian who worked under Brunelleschi and left many traces of his activity in Naples (Triumphal Arch), Sicily and southern France. Finally came Michelangelo, who raised the sculpture of the modern world to its highest pitch of magnificence, and at the same time sowed the seeds of its rapidly approaching decline; the head of his David at Florence is a work of unrivalled force and dignity. His rivals and imitators, Baccio Bandinelli, Giacomo della Porta, Montelupo, Ammanati and Vincenzo de’ Rossi (pupils of Bandinelli) and others, copied and exaggerated his faults without possessing a touch of his gigantic genius. In other parts of Italy, such as Pavia, the traditions of the 15th century lasted longer, though gradually fading. The Statuary and reliefs which make the Certosa near Pavia one of the most gorgeous buildings in the world are free from the influence of Michelangelo, which at Florence and Rome was overwhelming. Though much of the sculpture was begun in the second half of the 15th century, the greater part was not executed till much later. The magnificent tomb of the founder, Giovanni Galeazzo Visconti, was not completed till about 1560, and is a gorgeous example of the style of the Renaissance grown weak from excess of richness and from loss of the simple purity of the art of the 15th century. Everywhere in this wonderful building the fault is the same; and the growing love of luxury and display, which was the curse of the time, is reflected in the plastic decorations of the whole church. The old religious spirit had died out and was succeeded by unbelief or by an affected revival of paganism. Monuments to ancient Romans, such as those to the two Plinys on the façade of Como cathedral, or “heroa” to unsaintly mortals, such as that erected at Rimini by Sigismondo Pandolfo in honour of Isotta,[25] grew up side by side with shrines and churches dedicated to the saints. We have seen how the youthful vigour of the Christian faith vivified for a time the dry bones of expiring classic art, and now the decay of this same belief brought with it the destruction of all that was most valuable in medieval sculpture. Sculpture, like the other arts, became the bond-slave of the rich, and ceased to be the natural expression of a whole people. Though for a long time in Italy great technical skill continued to exist, the vivifying spirit was dead, and at last a dull scholasticism or a riotous extravagance of design became the leading characteristics.

The 16th century was one of transition to this state of degradation, but nevertheless produced many sculptors of great ability who were not wholly crushed by the declining taste of their time. John of Douai (1524–1608), usually known as Giovanni da Bologna, one of the ablest, lived and worked almost entirely in Italy. His bronze statue of Mercury flying upwards, in the Uffizi, one of his finest works, is full of life and movement. By him also is the “Carrying off of a Sabine Woman” in the Loggia de’ Lanzi. His great fountain at Bologna, with two tiers of boys and mei-maids, surmounted by a colossal statue of Neptune, a very noble work, is composed of architectural features combined with sculpture, and is remarkable for beauty of proportion. He also cast the fine bronze equestrian statue of Cosimo de Medici at Florence and the very richly decorated west door of Pisa cathedral, the latter notable for the overcrowding of its ornaments and the want of sculpturesque dignity in the figures; it is a feeble imitation of Ghiberti’s noble production. One of Giovanni’s best works, a group of two nude figures fighting, is now lost. A fine copy in lead existed till recently in the front quadrangle of Brasenose College, Oxford, of which it was the chief ornament. In 1881 it was sold for old lead by the principal and fellows of the college, and was immediately melted down by the plumber who bought it—an irreparable loss, as the only other existing copy is very inferior; the destruction was an utterly inexcusable act of vandalism. The sculpture on the western façade of the church at Loreto and the elaborate bronze gates of the Santa Casa are works of great technical merit by Girolamo Lombardo and his sons, about the middle of the 16th century. Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1569), though in the main greater as goldsmith than as sculptor, produced one work of great beauty and dignity—the bronze Perseus in the Loggia de' Lanzi at Florence. His large bust of Cosimo de’ Medici in the Bargello is mean and petty in style. A number of very clever statues and groups in terra-cotta were modelled by Antonio Begarelli of Modena (d. 1565), and were enthusiastically admired by Michelangelo; the finest are a “Pieta” in S. Maria Pomposa and a large “Descent from the Cross” in S. Francesco, both at Modena. The colossal bronze seated statue of Julius III. at Perugia, cast in 1555 by Vincenzio Danti, is one of the best portrait-figures of the time.

The latter part of the 15th century in France was a time of transition from the medieval style, which had gradually been deteriorating, to the more fiorid and realistic taste of the Renaissance. To this period belong a number of rich reliefs and statues on the choir-screen of Chartres cathedral. Those on The Renaissance in France.the screen at Amiens are later still, and exhibit the rapid advance of the new style.

The transition from the Gothic to the Renaissance is to be noted in many tomb monuments of the second half of the 15th and the beginning of the 16th centuries, notably in Rouland de Roux’s magnificent tomb of the cardinals of Amboise at Rouen cathedral. Italian motifs are paramount in the great tomb of Louis XII. and his wife Anne of Bretagne, at St Denis, by Jean Iuste of Tours.

The influx of Italian artists into France in the reign of Francis I., who, with Leonardo da Vinci, Andrea del Sarto, Rosso, and Primaticcio, had summoned Benvenuto Cellini and other Italian sculptors to his court, naturally led to the practical extinction of the Gothic style, though isolated examples of medievalism still occur about the The Italian influence. middle of the 16th century. Such are the “Entombment” in the crypt of Bourges cathedral, and the tomb of René of Chalons in the church of St Etienne at Bar-le-Duc. But the main current of artistic thought followed the direction indicated by the founding of the italianizing school of Fontainebleau. lean Goujon, (d. 1572) was the, ablest French sculptor of the time; he combined great technical skill and refinement of modelling with the florid and affected style of the age. His nude figure of “Diana reclining by a Stag,” now in the Louvre, is a graceful and vigorous piece of work, superior in sculpturesque breadth to the somewhat similar bronze relief of a nymph by Cellini. Between 1540 and 1552 Goujon executed the fine monument at Rouen to Duke Louis de Brézé, and from 1555 to 1562 was mainly occupied in decorating the Louvre with sculpture. One of the most pleasing and graceful works of this period, thoroughly Italian in style, is the marble group of the “Three Graces” bearing on their heads an urn containing the heart of Henry II., executed in 1560 by Germain Pilon for Catherine de Médicis. The monument of Catherine and Henry II. at St Denis, by the same sculptor, is an inferior and coarser work. Maître Ponce, probably the same as the Italian Ponzio Jacquio, chisel led the noble monument of Albert of Carpi (1535), now in the Louvre. Another very fine portrait effigy of about 1570, a recumbent figure in full armour of the duke of Montmorency, preserved in the Louvre, is the work of Barthelemy Prieur. François Duquesnoy of Brussels (1594–1644), usually known as Il Fiammingo, was a clever sculptor, thoroughly French in style, though he mostly worked in Italy. His large statues are very poor, but his reliefs in ivory of boys and cupids are modelled with wonderfully soft realistic power and graceful fancy.

To these sculptors should be added Jacques Sarrazin, well known for the colossal yet elegant caryatides for the grand pavilion of the Louvre; and François Augier, the sculptor of the splendid mausoleum of the duc de Montmorency.

In the Netherlands the great development of painting was not accompanied by a parallel movement in plastic art. Of the few monuments that claim attention, we must mention the bronze tomb of Mary of Burgundy at Notre-Dame, Bruges, executed about 1495 by Jan de Baker, and the less remarkable The Netherlands.though technically more complete companion tomb of Charles the Bold (1558).

The course of the Renaissance movement in German sculpture differs from that of most other countries in so far as it appears to grow gradually out of the Gothic style in the direction of individual, realistic treatment of the figure which in late Gothic days had become somewhat conventional and schematic and idealized. Marked Beginning of the Renaissance in Germany. physiognomic expression, careful rendering of movement, costume and details, and the suggestion of different textures, together with almost tragic emotional intensity, are the chief aims of the 15th-century sculptors who, on the whole, adhere to medieval thought and arrangement. The Italian influence, which did not make itself felt until the early days of the 16th century, led to brilliant results, whilst the workers retained their fresh northern individuality and keen observation of nature. But in the latter half of this century it began to choke these national characteristics, and led to somewhat theatrical and conventional classicism and mannerism.

One speciality of the 15th century was the production of an immense number of wooden altars and reredoses, painted and gilt in the most gorgeous way and covered with subject-reliefs and statues, the former often treated in a very pictorial style.[26] Wooden screens, stalls, tabernacles and other church-httings of the greatest elaboration and clever workmanship were largely produced in Germany at the same time, and on into the 16th century.[27] Jörg Syrlin, one of the most able of these sculptors in wood, executed the gorgeous choir-stalls in Ulm cathedral, richly decorated with statuettes and canopied work, between 1469 and 1474; his son and namesake sculptured the elaborate stalls in Blaubeuren church of 1496 and the great pulpit in Ulm cathedral. Another exceptionally important work of this type is the magnificent altar at St Wolfgang in Upper Austria, carved by the Tirolese, Michael Pacher, in 1481. Veit Stoss of Cracow, who later settled in Nuremberg, a man of bad character, was a most skilful sculptor in wood; he carved the high altar, the tabernacle and the stalls of the Frauenkirche at Cracow, between 1472 and 1494. One of his finest works is a large piece of wooden panelling, nearly 6 ft. square, carved in 1495, with central reliefs of the Doom and the Heavenly Host, framed by minute reliefs of scenes from Bible history. It is now in the Nuremberg town-hall. Wohlgemuth (1434–1519), the master of A. Dürer, was not only a painter but also a clever wood-carver, as was also Dürer himself (1471–1528), who executed a tabernacle for the Host with an exquisitely carved relief of Christ in Majesty between the Virgin and St John, which still exists in the chapel of the monastery of Landau. Dürer also produced miniature reliefs cut in boxwood and hone-stone, of which the British Museum (print-room) possesses one of the finest examples. Adam Krafft (c. 1455–1507) was another of this class of sculptors, but he worked also in stone; he produced the great Schreyer monument (1492) for St Sebald’s at Nuremberg,—a very skilful though mannered piece of sculpture, with very realistic figures in the costume of the time, carved in a way more suited to wood than stone, and too pictorial in effect. He also made the great tabernacle for the Host, 80 ft. high, covered with statuettes, in Ulm cathedral, and the very spirited “Stations of the Cross” on the road to the Nuremberg cemetery.

The Vischer family of Nuremberg for three generations were among the ablest sculptors in bronze during the 15th and 16th centuries. Hermann Vischer the elder worked mostly between 1450 and 1505, following the earlier medieval traditions, but without the originality of his son, Peter Vischer.