1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Sheep

SHEEP (from the Anglo-Saxon sceáp, a word common in various forms to Teutonic languages; e.g. the German Schaf), a name originally bestowed in all probability on the familiar domesticated ruminant (Ovis aries), but now extended to include its immediate wild relatives. Although many of the domesticated breeds are hornless, sheep belong to the family of hollow-horned ruminants or Bovidae (q.v.). Practically they form a group impossible of definition, as they pass imperceptibly into the goats. Both sexes usually possess horns, but those of the females are small. In the males the horns are generally angulated, and marked by line transverse wrinkles; their colour being greenish or brownish. They are directed outwards, and curve in an open spiral, with the tips directed outwards. Although there may be a fringe of hair on the throat, the males have no beard on the chin; and they also lack the strong odour characteristic of goats. Usually the tail is short; and in all the wild species the coat takes the form of hair, and not wool. Like goats, sheep have narrow upper molar teeth, very different from those of the oxen, and narrow hairy muzzles. Between the two middle toes, in most species, is lodged a deep glandular bag having the form of a retort with a small external orifice, which secretes an unctuous and odorous substance. This, tainting the herbage or stones over which the animal walks, affords the means by which, through the powerfully developed sense of smell, the neighbourhood of other individuals of the species is recognized. The crumen or suborbital face-gland, which is so largely developed and probably performs the same office in some antelopes and deer, is present, although in a comparatively rudimentary form, in most species, but is absent in others. Wild sheep attain their maximum development, both in respect of number and size, in Central Asia. They associate either in large flocks, or in family-parties; the old males generally keeping apart from the rest. Although essentially mountain animals, sheep generally frequent open, undulating districts, rather than the precipitous heights to which goats are partial. It may be added that the long tails of most tame breeds are, like wool, in all probability the results of domestication.

The Pamir plateau, on the confines of Turkestan, at an elevation of 16,000 ft. above the sea-level, is the home of the magnificent Ovis poli, named after the celebrated Venetian traveller Marco Polo, who met with it in the 13th century. It is remarkable for the great size of the horns of the old rams and the wide open sweep of their curve, so that the points stand boldly out on each side, far away from the animal's head, instead of curling round nearly in the same plane, as in most of the allied species. A variety inhabiting the Thian Shian is known as O. poli carelini. An even larger animal is the argali, O. ammon, typically from the Altai, but represented by one race in Ladak and Tibet (O. ammon hodgsoni), and by a second in Mongolia. Although its horns are less extended laterally than those of O. poli, they are grander and more massive. In their short summer coats the old rams of both species are nearly white. Ovis sairensis from the Sair mountains and, O. littledalei from Kulja are allied species. In the Stanovoi mountains and neighbouring districts of E. Siberia and in Kamchatka occur two sheep which have been respectively named O. borealis and O. nivicola. They are, however, so closely allied to the so-called bighorn sheep of N. America, that they can scarcely be regarded as more than local races of O. canadensis, or O. cervina, as some naturalists prefer to call the species. These bighorns are characterized by the absence of face-glands, and the comparatively smooth front surface of the horns of the old rams, which are thus very unlike the strongly wrinkled horns of the argali group. The typical bighorn is the khaki-coloured and white-rumped Rocky Mountain animal; but on the Stickin river there is a nearly black race, with the usual white areas (O. canadensis stonei), while this is replaced in Alaska by the nearly pure white O. c. dalli; the grey sheep of the Yukon (O. c. fannini) being perhaps not a distinct form. Returning to Asia, we find in Ladak, Astor, Afghanistan and the Punjab ranges, a sheep whose local races are variously known as urin, urial and shapo, and whose technical name is O. vignei. It is a smaller animal than the members of the argali group, and approximates to the Armenian and the Sardinian wild sheep or mouflon (Ovis orientalis and O. musimon) (see Mouflon). We have in Tibet the bharal or blue sheep, Ovis (Pseudois) bharal, and in N. Africa the udad or aoudad, O. (Ammotragus) lervia, both of which have no face-glands and in this and their smooth horns approximate to goats (see Bharal and Aoudad).

A Mouflon Ram (Ovis musimon).

The sheep was domesticated in Asia and Europe before the dawn of history, though unknown in this state in the New World until after the Spanish conquest. It has now been introduced by man into almost all parts of the world where agricultural operations are carried on, but flourishes especially in the temperate regions of both hemispheres. Whether this well-known and useful animal is derived from any one of the existing wild species, or from the crossing of several, or from some now extinct species, are matters of conjecture. The variations of external characters seen in the different breeds are very great. They are chiefly manifested in the form and number of the horns, which may be increased from the normal two to four or even eight, or may be altogether absent in the female alone or in both sexes; in the shape and length of the ears, which often hang pendent by the side of the head; in the peculiar elevation or arching of the nasal bones in some eastern races; in the length of the tail, and the development of great masses of fat at each side of its root or in the tail itself; and in the colour and quality of the fleece.

On the W. coast of Africa two distinct breeds of hairy sheep are indigenous, the one characterized by its large size, long limbs and smooth coat, and the other by its inferior stature, lower build and heavily maned neck and throat. Both breeds, which have short tails and small horns (present only in the rams), were regarded by the German naturalist Fitzinger as specifically distinct from the domesticated Ovis aries of Europe; and for the first type he proposed the name O. longipes and for the second O. jubata. Although such distinctions may be doubtful (the two African breeds are almost certainly descended from one ancestral form), the retention of such names may be convenient as a provisional measure.

The long-legged hairy sheep, which stands a good deal taller than a Southdown, ranges, with a certain amount of local variation, from Lower Guinea to the Cape. In addition to its long limbs, it is characterized by its Roman nose, large (but not drooping) ears, and the presence of a dewlap on the throat and chest. The ewes are hornless, but in Africa the rams have very short, thick and somewhat goatlike horns. On the other hand, in the W. Indian breed, which has probably been introduced from Africa, both sexes are devoid of horns. The colour is variable. In the majority of cases it appears to be pied, showing large blotches of black or brown on a white ground; the head being generally white with large black patches on the sides, most of the neck and the fore-part of the body black, and the hind-quarters white with large coloured blotches. On the other hand, these sheep may be uniformly yellowish white, reddish brown, greyish brown or even black. The uniformly reddish or chestnut-brown specimens approach most nearly to the wild mouflon or urial in colour, but the chestnut extends over the whole of the underparts and flanks; domestication having probably led to the elimination of the white belly and dark flank band, which are doubtless protective characters. The feeble development of the horns is probably also a feature due to domestication.

In Angola occurs a breed of this sheep which has probably been crossed with the fat-tailed Malagasy breed; while in Guinea there is a breed with lappets, or wattles, on the throat, which is probably the result of a cross with the lop-eared sheep of the same district. The Guinea lop-eared breed, it may be mentioned, is believed to inherit its drooping ears and throat wattles from an infusion of the blood of the Roman-nosed hornless Theban goat (see Goat). Hairy long-legged sheep are also met with in Persia, but are not pure-bred, being apparently the result of a cross between the long-legged Guinea breed and the fat-tailed Persian sheep.

The maned hairy sheep (Ovis jubata), which appears to be confined to the W. coast of Africa, takes its name from a mane of longish hair on the throat and neck; the hair on the body being also longer than in the ordinary long-legged sheep. This breed is frequently black or brown and white; but in a small sub-breed from the Cameroons the general colour is chestnut or foxy red, with the face, ears, buttocks, lower surface of tail and under-parts black. The mbst remarkable thing about this Cameroon sheep is, however, its extremely diminutive size, a full-grown ram standing only 19 in. at the withers.

In point of size this pigmy Cameroon breed comes very close to an exceedingly small sheep of which the limb-bones have been found in certain ancient deposits in the S. of England; and the question arises whether the two breeds may not have been nearly related. Although there are no means of ascertaining whether the extinct pigmy British sheep was clothed with hair or with wool, it is practically certain that some of the early European sheep retained hair like that of their wild ancestor; and there is accordingly no prima facie reason why the breed in question should not have been hairy. On the other hand, since the so-called peat-sheep of the prehistoric Swiss lake-dwellers appears to be represented by the existing Graubünden (Grisons) breed, which is woolly and coloured something like a Southdown, it may be argued that the former was probably also woolly, and hence that the survival of a hairy breed in a neighbouring part of Europe would be unlikely. The latter part of the argument is not very convincing, and it is legitimate to surmise that in the small extinct sheep of the S. of England we may have a possible relative of the pigmy hairy sheep of W. Africa.

Fat-rumped sheep, Ovis steatopyga, are common to Africa and Asia, and are piebald with rudimentary horns, and a short hairy coat, being bred entirely for their milk and flesh. In fat-tailed sheep, on the other hand, which have much the same distribution, the coat is woolly and generally piebald. Four-horned sheep are common in Iceland and the Hebrides; the small half-wild breed of Soa often showing this reduplication. There is another four-horned breed, distinguished by its black (in place of brown) horns, whose home is probably S. Africa. In the unicorn sheep of Nepal or Tibet the two horns of the rams are completely welded together. In the Himalayan and Indian hunia sheep, the rams of which are specially trained for fighting, and have highly convex foreheads, the tail is short at birth. Most remarkable of all is the so-called Wallachian sheep, or Zackelschaf (Ovis strepsiceros), represented by several more or less distinct breeds in E. Europe, in which the long upright horns are spirally twisted like those of the mazkhor wild goat.

For the various breeds of wild sheep see R. Lydekker, Wild Oxen, Sheep and Goats (London, 1898), and later papers in the Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Also Rowland Ward, Records of Big Game (5th ed., London, 1906). (R. L.*)

Modern British Breeds of Sheep.—The sheep native to the British Isles may be classified as the lowland and the mountain breeds, and subdivided into long wools and short wools—the latter including the Down breeds, sometimes termed black-faced. The longwool breeds are the Leicester, Border Leicester, Cotswold, Lincoln, Kent, Devon Longwool, South Devon, Wensleydale and Roscommon. The shortwool breeds are the Oxford Down, Southdown, Shropshire, Hampshire Down, Suffolk, Ryeland, Dorset and Somerset Horn, Kerry Hill, Radnor and Clun Forest. The mountain breeds include the Cheviot, Scotch Black-face, Lonk, Rough Swaledale, Derbyshire Gritstone, Penistone, Limestone, Herdwick, Dartmoor, Exmoor and Welsh Mountain. These breeds are all English, except the Border Leicester, Cheviot and Scotch Black-face, which belong to Scotland; the Welsh Mountain, which belongs to Wales; and the Roscommon, which is Irish. The majority of the true mountain breeds are horned, the males only in the cases of Cheviot, Herdwick, Penistone and Welsh, though most Cheviot and many Herdwick rams are hornless. Of Derbyshire Gritstone neither sex has horns. In the other horned breeds, the Dorset and Somerset, Limestone, Exmoor, Old Norfolk, and Western or Old Wiltshire, both sexes have horns. The remaining breeds are hornless. The white-faced breeds include the Leicester, Border Leicester, Lincoln, Kentish, Cheviot, Ryeland, Devon Longwool, South Devon, Dorset and Somerset Horn, Limestone, Penistone, Exrnoor and Roscommon.

The Leicester, though now not numerous, is of high interest. It was the breed which Robert Bakewell took in hand in the 18th century, and greatly improved by the exercise of his skill and judgment. Bakewell lived at Dishley Grange, Leicestershire, and in France the Leicester sheep are still called Dishleys. In past times Leicester blood was extensively employed in the improvement or establishment of other longwool breeds of sheep. The Leicester, as seen now, has at white wedge-shaped face, the forehead covered with wool; thin mobile ears; neck full towards the trunk, short and level with the back; width over the shoulders and through the heart; a full broad breast; fine clean legs standing well apart; deep round barrel and great depth of carcass; firm flesh, springy pelt, and pink skin, covered with fine, curly, lustrous wool. The breed is maintained pure upon the rich pastures of Leicestershire, E. and N. Yorkshire, Cheshire, Cumberland and Durham, but its chief value is for crossing, when it is found to promote maturity and to improve the fattening propensity.

The Border Leicester originated after the death in 1795 of Bakewell, when the Leicester breed, as it then existed, diverged into two branches. The one is represented by the breed still known in England as the Leicester. The other, bred on the Scottish Borders, with an early admixture of Cheviot blood, acquired the name of Border Leicester. The distinguishing characteristics of the latter are: that it is an upstanding animal of gay appearance with light offal; and has a long though strong neck carrying a long, lean, clean head covered with white, hard, but not wiry hair, free from wool, long highset ears and a black muzzle; back broad and muscular, belly well covered with wool; legs clean, and a fleece of long white wavy wool, arranged in characteristic locks or pirls.

The Blue-faced Wensleydales take their name from the Yorkshire dale of which Thirsk is the centre. They are longwool sheep, derived from the old Teeswater breed by crossing with Leicester rams. They have a tuft of wool on the forehead. The skin of the body is sometimes blue, whilst the wool has a bright lustre, is curled in small distinct pirls, and is of uniform staple. The rams are in much favour in Scotland and the N. of England for crossing with ewes of the various black-faced horned mountain breeds to produce mutton of superior quality and to use the cross-ewes to breed to a pure longwool or sometimes a Down ram.

The Cotswold is an old-established breed of the Gloucestershire hills, extending thence into Oxfordshire. It was but slightly crossed for improvement by the Dishley Leicesters and has retained its characteristic type for generations. They are big, handsome sheep, with finely-arched necks and graceful carriage. With their broad, straight backs, curved ribs; and capacious quarters, they carry a great weight of carcass upon strong, wide-standing legs. The fine white fleece of long wavy wool gives the Cotswold an attractive appearance, which is enhanced by its topknot or forelock. The mutton of the Cotswolds is not of high quality except at an early age, but the sheep are useful for crossing purposes to impart size, and because they are exceptionally hardy.

The Lincolns are descended from the old native breed of Lincolnshire, improved by the use of Leicester blood. They are hardy and prolific, but do not quite equal the Cotswolds in size. They have larger, bolder heads than the Leicesters. Breeders of Lincoln rams like best a darkish face, with a few black spots on the ears; and white legs. The wool has a broad staple, and is denser and longer, and the fleece heavier, than in any other British breed. For this reason it has been the breed most in favour with breeders in all parts of the world for mating with Merino ewes and their crosses. The progeny is a good general-purpose sheep, giving a large fleece of wool but only a medium quality of mutton. With a greater proportion of Lincoln blood in the mixed flocks of the world there is a growing tendency to produce finer mutton by using Down rams, but at the sacrifice of part of the yield of wool. In 1906 Henry Dudding, of Riby Grove, Lincolnshire, obtained at auction the sum of 1450 guineas for a Lincoln ram bred by him,—the highest price paid for a sheep in the United Kingdom. In the same year Robert and William Wright, of Nocton Heath, Lincoln, sold their flock of 950 animals to Señor Manuel Cobo, Buenos Aires, for £30,000.

The Devon Longwool is a breed locally developed in the valleys of W. Somerset, N. and E. Devon, and parts of Cornwall. It originated in a strong infusion of Leicester blood amongst the old Bampton stock of Devonshire. The Devon Longwool is not unlike the Lincoln, but is coarser. It is white-faced, with a lock of wool on the forehead.

The South Devon or South Dum are, like the cattle of that name, a strictly local breed, which likewise exemplify the good results of crossing with the Leicesters. The South Devons have a fairly fine silky fleece of long staple, heavier than that of the Devon Longwool, which it also excels in size.

The Roscommon—the one breed of modern sheep native to Ireland—is indebted for its good qualities largely to the use of Leicester blood. It is a big-bodied, high-standing sheep, carrying a long, wavy, silky fleece. It ranges mainly from the middle of Ireland westwards, but its numbers have declined considerably in competition with the Shropshire.

The Kent or Romney Marsh is native to the rich tract of grazing land on the S. coast of Kent. They are hardy, white-faced sheep, with a close-coated longwool fleece. They were gradually, like the Cotswolds, improved from the original type of slow-maturity sheep by selection in preference to the use of rams of the Improved Leicester breed. With the exception of the Lincoln, no breed has received greater distinction in New Zealand, where it is in high repute for its hardiness and general usefulness. When difficulties relating to the quantity and quality of food arise the Romney is a better sheep to meet them than the Lincolns or other longwools.

The Oxford Down is a modern breed which owes its origin to crossing between Cotswolds and Hampshire Downs and Southdowns. Although it has inherited the forelock from its longwool ancestors, it approximates more nearly to the shortwool type, and is accordingly classified as such. An Oxford Down ram has a bold masculine head; the poll well covered with wool and the forehead adorned by a topknot; ears self-coloured, upright, and of fair length; face of uniform dark brown colour; legs short, dark, and free from spots; back level and chest wide; and the fleece heavy and thick. The breed is popular in Oxford and other midland counties. Its most notable success in recent years is on the Scottish and English borders, where, at the annual ram sales at Kelso, a greater number of rams is auctioned of this than of any other breed, to cross with flocks of Leicester-Cheviot ewes especially, but also with Border Leicesters and three-parts-bred ewes. It is supplanting the Border Leicester as a sire of mutton sheep; for, although its progeny is slower in reaching maturity, tegs can be fed to greater weights in spring—65 to 68 ℔ per carcass—without becoming too fat to be classed as finest quality.

The Southdown, from the short close pastures upon the chalky soils of the South Downs in Sussex, was formerly known as the Sussex Down. In past times it did for the improvement of the shortwool breeds of sheep very much the same kind of work that the Leicester performed in the case of the longwool breeds. A pure-bred Southdown sheep has a small head, with a light brown or brownish grey (often mouse-coloured) face, fine bone, and a symmetrical, well-fleshed body. The legs are short and neat, the animal being of small size compared with the other Down sheep. The fleece is of fine, close, short wool, and the mutton is excellent. “Underhill” flocks that have been kept for generations in East Anglia, on the Weald, and on flat meadow land in other parts of the country, have assumed a heavier type than the original “Upperdown” sheep. It was at one time thought not to be a rent-paying breed, but modern market requirements have brought it well within that category.

The Shropshire is descended from the old native sheep of the Salopian hills, improved by the use of Southdown blood. Though heavier in fleece and a bulkier animal, the Shropshire resembles an enlarged Southdown. As distinguished from the latter, however, the Shropshire has a darker face, blackish brown as a rule, with very neat ears, whilst its head is more massive, and is better covered with wool on the top and at the sides. This breed has made rapid strides in recent years, and it has acquired favour in Ireland as well as abroad. It is an early-maturity breed, and no other Down produces a better back to handle for condition—the frame is so thickly covered with flesh and fat.

The Hampshire Down is another breed which owes much of its improved character to an infusion of Southdown blood. Early in the 19th century the old Wiltshire white-faced horned sheep, with a scanty coat of hairy wool, and the Berkshire Knot, roamed over the downs of their native counties. Only a remnant of the former under the name of the Western sheep survives in a pure state, but their cross descendants are seen in the modern Hampshire Down, which originated by blending them with the Southdown. Early maturity and great size have been the objects aimed at and attained, this breed, more perhaps than any other, being identified with early maturity. One reason for this is the early date at which the ewes take the ram. Whilst heavier than the Shropshire, the Hampshire Down sheep is less symmetrical. It has a black face and legs, a big head with Roman nose, darkish ears set well back, and a broad level back (especially over the shoulders) nicely filled in with lean meat.

The Dorset Down or West Country Down, “a middle type of Down sheep pre-eminently suited to Dorsetshire,” is a local variety of the Hampshire Down breed, separated by the formation of a Dorset Down sheep society in 1904, about eighty years after the type of the breed had been established.

The Suffolk is another Down, which took its origin about 1790 in the crossing of improved Southdown rams with ewes of the old black-face Horned Norfolk, a breed still represented by a limited number of animals. The characteristics of the latter are retained in the black face and legs of the Suffolk, but the horns have been bred out. The fleece is moderately short, the wool being of close, fine, lustrous fibre, without any tendency to mat. The limbs, woolled to the knees and hocks, are clean below. The breed is distinguished by having the smoothest and blackest face and legs of all the Down breeds and no wool on the head. Although it handles hard on the back when fat, no breed except the old Horned Norfolk equals it in producing a saddle cut of mutton with such an abundance of lean red meat in proportion to fat. It carried off the highest honours in the dressed carcass competition at Chicago in 1903, and the championship in the “block test” at Smithfield Club Show was won for the five years 1902–1906 by Suffolks or Suffolk cross lambs from big-framed Cheviot ewes. In 1907, the championship went to a Cheviot wether, but in the two pure, short-woolled classes all the ten awards were secured by Suffolks, and in the two cross-bred wether classes nine of the ten awards went to a Suffolk cross. The mutton of all the Down breeds is of superior quality, but that of the Suffolk is pre-eminently so.

The Cheviot takes its name from the range of hills stretching along the boundary between England and Scotland, on both sides of which the breed now extends, though larger types are produced in East Lothian and in Sutherlandshire. The Cheviot is a hardy sheep with straight wool, of moderate length and very close-set, whilst wiry white hair covers the face and legs. Put to the Border Leicester ram the Cheviot ewe produces the Half-bred, which as a breeding ewe is unsurpassed as a rent-paying, arable-land sheep.

The Scotch Black-face breed is chiefly reared in Scotland, but it is of N. of England origin. Their greater hardiness, as compared with the Cheviots, has brought them into favour upon the higher grounds of the N. of England and. of Scotland, where they thrive upon heather hills and coarse and exposed grazing lands. The colour of face and legs is well-defined black and white, the black predominating. The spiral horns are low at the crown, with a clear space between the roots, and sweep in a wide curve, sloping slightly backwards, and clear of the cheek. The fashionable fleece is down to the ground, hairy and strong, and of uniform quality throughout.

The Lonk has its home amongst the moorlands of N. Lancashire and the W. Riding of Yorkshire, and it is the largest of the mountain breeds of the N. of England and Scotland. It bears most resemblance to the Scotch Black-face, but carries a finer, heavier fleece, and is larger in head. Its face and legs are mottled black and white, and its horns are strong. The tail long and rough.

The Herdwick is the hardiest of all the breeds thriving upon the poor mountain land in Cumberland and Westmorland. The rams sometimes have small, curved, wide horns like those of the Cheviot ram. The colour of the fleece is white, with a few darkish spots here and there; the faces and legs are dark in the lambs, gradually becoming white or light grey in a few years. The wool is strong and coarse, standing up round the shoulders and down the breast like a mane. The forehead has a topknot, and the tail is well covered.

The Limestone is a breed of which little is heard. It is almost restricted to the fells of Westmorland, and is probably nearly related to the Scotch Black-face. The breed does not thrive off its own geological formation, and the ewes seek the ram early in the season. The so-called “Limestones” of the Derbyshire hills are really Leicesters.

The Welsh Mountain is a small, active, soft-woolled, white-faced breed of hardy character. The legs are often yellowish, and this colour may extend to the face. The mutton is of excellent quality. The ewes, although difficult to confine by ordinary fences, are in high favour in lowland districts for breeding fattening lambs to Down and other early maturity rams.

The Clun Forest is a local breed in W. Shropshire and the adjacent part of Wales. It is descended from the old Tan-faced sheep. It is now three parts Shropshire, having been much crossed with that breed, but its wool is rather coarser.

The Radnor is short-limbed and low-set with speckled face and legs. It is related to the Clun Forest and the Kerry Hill sheep. The draft ewes of all three breeds are in high demand for breeding to Down and longwool rams in the English midlands.

The Ryeland breed is so named from the Ryelands, a poor upland district in Herefordshire. It is a very old breed, against which the Shropshires have made substantial headway. Its superior qualities in wool and mutton production have been fully demonstrated, and a demand for rams is springing up in S. as well as in N. America. The Ryeland sheep are small, hornless, have white faces and legs, and remarkably fine short wool, with a topknot on the forehead.

The Dartmoor, a hardy local Devonshire breed, is a large hornless, longwool, white-fleeced sheep, with a long mottled face. It has been attracting attention in recent years.

The Exmoor is a horned breed of Devonshire moorland, one of the few remaining remnants of direct descent from the old forest breeds of England. They have white legs and faces and black nostrils. The coiled horns lie more closely to the head than. in the Dorset and Somerset Horn breed. The Exmoors have a close, fine fleece of short wool. They are very hardy, and yield mutton of choice flavour.

The Dorset and Somerset Horn is an old west-country breed of sheep. The fleece is fine in quality, of close texture, and the wool is intermediate between long and short, whilst the head carries a forelock. Both sexes have horns, very much coiled in the ram. The muzzle, legs and hoofs are white; the nostrils pink. This is a hardy breed, in size somewhat exceeding the Southdown. The special characteristic of the breed is that the ewes take the ram at an unusually early period of the year, and cast ewes are in demand for breeding house lamb for Christmas. Two crops of lambs in a year are sometimes obtained from the ewes, although it does not pay to keep such rapid breeding up regularly.

The Merino is the most widely distributed sheep in the world. It has been the foundation stock of the flocks of all the great sheep countries. A few have existed in Britain for more than a hundred years. They thrive well there, as they do everywhere, but they are wool-sheep which produce slowly a secondary quality of mutton—thin and blue in appearance. The Merino resemble the Dorset Horn breed. The rams possess large coiling horns—the ewes may or may not have them. The muzzle is flesh-coloured and the face covered with wool. The wool, densely set on a wrinkled skin, is white and generally fine, although it is classified into long, short, fine and strong. Merino cross with early-maturity longwool, Down, or other close-wooled rams, are good butchers' sheep, and most of the frozen mutton imported into the United Kingdom has had more or less of a merino origin. (W. Fr.; R. W.)

|

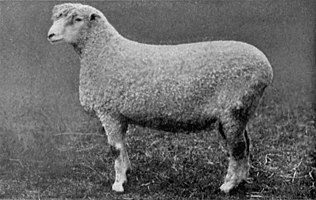

| From a photo in Professor Robert Wallace's Farm Live Stock of Great Britain (4th edition). |

| Champion Merino Ram. |

Lowland Sheep-breeding and Feeding.—A Shropshire flock of about two hundred breeding ewes is here taken as a typical example of the numerous systems of managing sheep on a mixed farm of grazing and arable land. The ewes lamb from early in January till the end of February. The lambs have the shelter of a lambing shed for a few days. When drafted to an adjoining field they run in front of their mothers and get a little crushed oats and linseed cake meal, the ewes receiving kail or roots and hay to develop milk. Swedes gradually give place to mangolds, rye and clover before the end of April, when shearing of the ewe flock begins, to be finished early in May. At this time unshorn lambs are dipped and dosed with one of Cooper's tablets of sulphur-arsenic dip material to destroy internal parasites. The operation is repeated in September. The lambs are weaned towards the end of June and the ewes run on the poorest pasture till August to lose surplus fat. In August the ewes are culled and the flock made up to its full numbers by selected shearling ewes. All are assorted and mated to suitable rams. Most of the older ewes take the ram in September, but maiden ewes are kept back till October. During the rest of the year the ewes run on grass and receive hay when necessary, with a limited amount of dry artificial food daily, ¼ ℔ each, gradually rising as they grow heavy in lamb to 1 ℔ per day. Turnips before lambing, if given in liberal quantities, are an unsafe food. To increase the number of doubles, ewes are sometimes put on good fresh grass, rape or mustard a week before the tups go out—a ram to sixty ewes is a usual proportion, though with care a stud ram can be got to settle twice the number. With good management twenty ewes of any of the lowland breeds should produce and rear thirty lambs, and the proportion can be increased by breeding from ewes with a prolific tendency. The period of gestation of a ewe is between 21 and 22 weeks, and the period oestrum 24 hours. If not settled the ewe comes back to the ram in from 13 to 18 (usually 16) days. To indicate the time or times of tupping three colours of paint are used. The breast of the ram is rubbed daily for the first fortnight with blue, for a similar period with red, and finally with black.

Fattening tegs usually go on to soft turnips in the end of September or beginning of October, and later on to yellows, green-rounds and swedes and, in spring and early summer, mangolds. The roots are cut into fingers and supplemented by an allowance of concentrated food made up of a mixture of ground cakes and meal, ¼ ℔ rising to about ½ ℔; and ½ ℔ to 1 ℔ of hay per day. The dry substance consumed per 100 ℔ live weight in a ration of ½ ℔ cake and corn, 12 ℔ roots and 1 ℔ hay daily, would be 16½ ℔ per week, and this gives an increase of nearly 2% live weight or 1 ℔ of live weight increase for 8¼ ℔ of dry food eaten. Sheep finishing at 135 ℔ live weight yield about 53% of carcass or over 70 ℔ each.

Management of Mountain Breeds.—Ewes on natural pastures receive no hand feeding except a little hay when snow deeply covers the ground. The rams come in from the hills on the 1st of January and are sent to winter on turnips. Weak ewes, not safe to survive the hardships of spring, are brought in to better pasture during February and March. Ewe hogs wintered on grass in the low country from the 1st of November are brought home in April, and about the middle of April on the average mountain ewes begin to lamb. One lamb at weaning time for every ewe is rather over the normal amount of produce. Cheviot and cross-bred lambs are marked, and the males are castrated, towards the end of May. Nearly a month later black-face lambs are marked and the eild sheep are shorn—the shearing of milch ewes being delayed till the second week of July. Towards the end of July sheep are all dipped to protect them from maggot flies (which are generally worst during August) with materials containing arsenic and sulphur, like that of Cooper and Bigg. Fat wethers for the butcher are drafted from the hills in August and the two succeeding months. Lamb sales are most numerous in August, when lowland farmers secure their tegs to feed in winter. In this month breeding ewes recover condition and strength to withstand the winter storms. Ram auctions are on in September and draft ewe sales begin and continue through October. Early this month winter dipping is done at midday in dry weather. Early in November stock sheep having lost the distinguishing “buist” put on at clipping time with a large iron letter dipped in hot tar, have the distinctive paint or kiel mark claimed by the farm to which they belong rubbed on the wool. The rams are turned out to the hills between the 15th and the 24th of November. Lowland rams put to breed half-bred and cross lambs receive about 1 ℔ of grain daily to prevent their falling off too rapidly in condition, as they would do if exclusively supported on mountain fare.

Literature.—D. Low, Breeds of the Domestic Animals of the British Isles (1842, illustrated, and 1845); R. Wallace, Farm Live Stock of Great Britain (1907); J. Coleman, Sheep of Great Britain (1907), and the Flock Books of the various breed societies. (R. W.)

Plate I.