1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Shenandoah Valley Campaigns

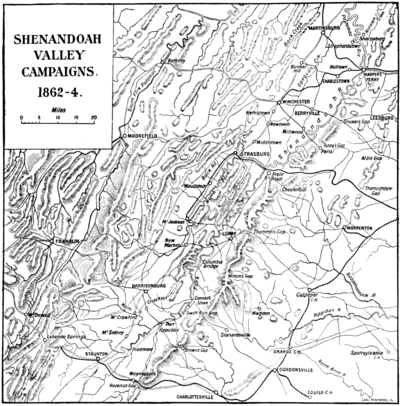

SHENANDOAH VALLEY CAMPAIGNS. During the American Civil War the Shenandoah Valley was frequently the scene of military operations, and at two points in the war these operations rose to the height of separate campaigns possessing great significance in the general development of the war. From a military point of view the Shenandoah Valley was valuable to the army which controlled it as a requisitioning area, for in this fertile region crops and cattle were plentiful. There were, moreover, numerous mills and factories. For the Confederates the Valley was also a recruiting area. A macadamized road from Lexington via Staunton and Winchester to Martinsburg gave them easy access to Maryland and enabled them to cover Lynchburg from the north. By a system of railways which united at Gordonsville and Charlottesville troops from Richmond and Lynchburg were detained within easy distance of five good passes over Blue Ridge, and as Strasburg in the valley lies almost due west of Washington it was believed in the North that a Confederate army thereabouts menaced a city the protection of which was a constant factor in the Federal plan of campaign. The Valley was 60 m. wide at Martinsburg and had been cleared of timber, so that the movements of troops were not restricted to the roads: the creeks and rivers were fordable at most places in summer by levelling the approaches: the terrain was specially suitable for mounted troops. The existence of the parallel obstacle between Strasburg and Newmarket, the two forks of the Shenandoah river enclosing the Massanutton range, afforded opportunities for strategic manoeuvres.

In the spring of 1862 the immense army organized by General McClellan advanced and threatened to sweep all before it. The Confederates, based on Richmond, were compelled to show a front westward to the Alleghanies, northward to the Potomac and eastwards to the Atlantic. The main armies were engaged on the Yorktown peninsula and the other operations were secondary. Yet in one instance a Confederate detachment that varied in strength between 5000 and 17,000 contrived to make some stir in the world and won renown for its commander. General Thomas J. Jackson with small means achieved great results, if we look at the importance which politics played in the affairs of the belligerents; and even in a military sense he was admirable for skilfully utilizing his experiences, so that his discomfiture's of the winter of 1861, when Rosecrans and Lander and Kelley were opposed to him, taught him how to deal with such Federal leaders as Shields and Banks, Milroy and Frémont, fettered as they all were by the Lincoln administration. The Valley operations in 1862 began by a retrograde movement on the part of the Confederates, for Jackson on their 12th of March retired from Winchester, and Banks at the head of 20,000 men took possession. Banks pushed a strong detachment under General Shields on to Strasburg a week later, and Jackson then withdrew his small division (5000) to Mount Jackson, so yielding the Shenandoah Valley for 40 m. south of Winchester. He was now acting under instructions to employ the invaders in the Valley and prevent any large body being sent eastward to reinforce their main army; but he was not to expose himself to the danger of defeat. He was to keep near the enemy, but not so near as to be compelled to fight Banks's superior forces. Such instructions, however, were difficult to carry out. When, on the 21st of March, Banks recalled Shields in accordance with orders from Washington, Jackson conceived that he was bound to follow Shields, and, when Shields stood at bay at Kernstown on the 23rd of March with 7000 men, Jackson at the head of 3500 attacked and was badly beaten.

For such excess of zeal two years later Sigel was removed from his command. But in 1862 apparently such audacity was true wisdom, for the proof thus afforded by Jackson of his inability to contend with Shields seems to have been regarded by the Federal authorities as an excuse for reversing their plans: Shields was reinforced by Williams's division, and with this force Banks undertook to drive Jackson from the Valley. A week after the battle of Kernstown, Banks moved to Strasburg with 16,000 men, and a month later (April 29) is found at Newmarket, after much skirmishing with Jackson's rear-guard which burnt the bridges in retiring. Meanwhile Jackson had taken refuge in the passes of Blue Ridge, where he too was reinforced. Ewell's division joined him at Swift Run Gap, and at the beginning of May he decided to watch Banks with Ewell's division and to proceed himself with the remainder of his command to join Edward Johnson's division, then beset by General Milroy west of Staunton. Secretly moving by rail through Rockfish Gap, Jackson united with Johnson and in a few days located Milroy at the village of McDowell. After reconnaissance Jackson concentrated his forces on Setlington Hill and proposed to attack on the morrow (May 8th), but on this occasion the Federals (Milroy having just been joined by Schenck) took the initiative, and after a four hours' battle Jackson was able to claim his first victory. The Confederates lost 500 out of 6000 men and the Federals 250 out

Jackson's

campaign.

of 2500 men. Jackson's pursuit of Milroy and Schenck was profitless, and he returned to his camp at McDowell on the 14th of May. Meanwhile General Banks had been ordered by President Lincoln to fall back from Newmarket, to send Shields's division to reinforce General McDowell at Fredericksburg, to garrison Front Royal and to entrench the remainder of his command at Strasburg: and in this situation the enemy found him on the 22nd of May. Jackson's opportunity had come to destroy Banks's force completely. The Confederates numbered 16,000, the Federals only 6000 men. Jackson availed himself of the Luray Valley route to intercept Banks after capturing the post at Front Royal. He captured the post, but failed to intercept Banks, who escaped northwards by the turnpike road and covered his retreat across the Potomac by a rear-guard action at Winchester on the 25th of May. Jackson followed and reached Halltown a few days later. But his stay there was of brief duration, for McDowell was moving westward from Fredericksburg and Frémont eastward from Franklin under instructions from Washington to intercept him. On the 31st of May Frémont had reached Cedar Creek, McDowell was at Front Royal and Jackson had retired to Strasburg, where he was compelled to wait for a detachment to come in. This rejoined on the evening of the 1st of June. Ewell's division held Frémont back until Jackson was on his way to Newmarket.

McDowell had sent Shields up the Valley by the Luray route But Jackson gained Newmarket in safety and destroyed the bridge by which Shields could emerge from the Luray Valley to join Frémont, who was left to cope with Jackson single-handed.Cross

Keys and

Port

Republic. Jackson's rearguard destroyed the bridges and otherwise impeded Frémont's advance, but a week later (June 7th) Frémont at Harrisonburg located his enemy at and next day he attacked with 10,500 men. Shields was still at Luray. Jackson held Fremont with Ewell's division (8000) and with the remainder proceeded to the left bank

of the Shenandoah near Port Republic to await developments, for Shields had pushed forward a strong advanced guard under General Tyler, whose vanguard (two squadrons) crossed the river while Frémont was engaged with Ewell. Tyler's cavalry was driven back with heavy loss. Jackson retained possession of the bridge by which Tyler and Frémont could unite, and next day he crossed the river to attack Tyler's two brigades. The engagement of the 9th of June is called the battle of Port Republic. Jackson with 13,000 men attacked Tyler with 3000 men, and Tyler, after stoutly resisting in the vain hope that the main body under Shields would come up from Conrad's Store or that Frémont would cross the river and fall upon Jackson, retired with a loss of some 800 men, leaving as many Confederates hors de combat. Tyler's brave efforts were in vain, for Shields had once more received orders from Washington which appeared to him to justify leaving his detachment to its fate, and Frémont could not reach the river in time to save the bridge, which Ewell's rear-guard burnt after Jackson had concentrated his forces against Tyler on the right bank. A few days later Jackson received orders to quit the Valley and join the main army before Richmond, and President Lincoln simultaneously discovered that he could not afford to keep the divisions of Frémont, Banks and McDowell engaged in operations against Jackson: so the Valley was at peace for a time.

In stricter connexion with the operations of the main armies in Virginia, the Confederates brought off two great soups in the Valley—Jackson's capture of Harper's Ferry and Martinsburg in the autumn of 1862 and Ewell's expulsion of Milroy from Martinsburg and Winchester in June 1863. The concentration of the Federal forces in N. Virginia in May 1864 for the campaign which ultimately took Grant and Lee south of the James involved a fresh series of operations in the Valley. At first a Union containing force was placed there under Sigel; this general, however, took the offensive and unwisely accepted battle and was defeated at Newmarket. Next Hunter, who superseded Sigel in command in West Virginia and the Valley, was to co-operate with the Army of the Potomac by a movement on Staunton and thence to Gordonsville and Lynchburg, with the object of destroying the railways and canal north of the James river by which troops and supplies reached the Confederates from the West. Sigel meanwhile was to cover the Ohio railroad at Martinsburg. Hunter encountered Jones's division at Piedmont (Mount Crawford) on the 5th of June and caused General Lee to detach from his main army a division under Breckinridge to aid Jones. Grant then detached Sheridan to join Hunter at Charlottesville, but Lee sent Hampton's cavalry by a shorter route to intercept Sheridan, and a battle at Trevillian Station compelled Sheridan to return and leave Hunter to his fate. The losses in this cavalry combat exceeded 1000, for the dense woods, the use of barricades and the armament of the mounted troops caused both sides to fight on foot until lack of ammunition brought the action to an end. Sheridan during his three months' command of the Federal cavalry had steadfastly adhered to the principle of always fighting the enemy's cavalry, and, though now compelled to return to the Pamunkey, he contrived to draw Hampton's force after him in that direction. Meanwhile on the 13th of June General Early had moved from Cold Harbor to add his command to the Confederate forces in the Valley. Early succeeded in interposing between Hunter and Lynchburg, and within a week drove Hunter out of Virginia by the Kanawha river route. Early then moved down the Valley turnpike unmolested. Expelling Sigel from Martinsburg on the 4th of July and crossing the Potomac opposite Sharpsburg, he soon appeared before Washington, after defeating an improvised force under Lew Wallace on the Monocacy. Grant then detached Wright's corps (VI.) from Petersburg and called Emory's corps (XIX.) from the West to oppose Early, who after creating serious alarm retired, on the 13th of July, by Leesburg and Snicker's Gap into the Valley at Winchester. Hunter had meanwhile gained Harper's Ferry via the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and, when Early withdrew towards Strasburg, General Crook collected the forces of Hunter and Sigel to follow the Confederates, but Early turned upon Crook and drove him back to the Potomac. Early then sent a detachment into Maryland to burn the town of Chambersburg. The alarm in the North for the safety of Washington was only quieted by the appointment of General Sheridan to command in the Valley.

He arrived on the scene early in August. His mission was

to drive Early up the Valley or, if the Confederates crossed into

Maryland, to intercept their return, and in any case,

he was to destroy all supplies in the country whichSheridan's

campaign.

could not be consumed by his own army. Sheridan

made Harper's Ferry his headquarters and concentrated at

Halltown. Early retained his position about Bunker's Hill,

destroyed the Ohio railroad, and held the main road up the

Valley until Sheridan moved out in force on the 10th of August.

Early then retreated up the Valley to Fisher's Hill (Strasburg),

where he expected to be joined by Anderson's corps from

Richmond. Sheridan had followed Early, but hearing of this

reinforcement to the enemy, he decided to take up a defensive

line at Halltown—the only point in the Valley which

did not favour flanking operations—and await reinforcements.

Sheridan's retrograde movement from Cedar Creek on the I7th

of August was, however, regarded in the North as a sign of

pusillanimity, and his removal from the Valley command was

loudly called for. During the retreat Sheridan's cavalry encountered

Early's reinforcements, Anderson's corps and Fitz

Lee's cavalry, about Winchester. Early had observed the

Federal movements from the heights south of Strasburg, and

now followed Sheridan down to Halltown. On the 21st of August

he again attacked Sheridan at Summit Point south of Charlestown.

A few days later Early detached a force to raid Williamsport,

and concentrated his main body behind the Opequan

near Bunker's Hill, leaving outposts on the railway, a position

which he held at the end of August. Sheridan meanwhile h ad

moved out between the Shenandoah and the Opequan to seize

all routes towards Washington, from Martinsburg on Early's

left as far up as the Winchester-Berryville turnpike by which

his own reinforcements reached the Valley through Snicker's

Gap. Sheridan also held the Smithfield crossing of the Opequan

in Early's front. Each commander, however, hesitated to bring

on a battle, Sheridan because the result of the Presidential

election would be seriously affected by his defeat at this moment,

and Early because with his inferior forces he was content to

know that his position on Sheridan's flank effectively covered

the Valley. But Sheridan was now at the head of the most

formidable army that had ever invaded this region. It consisted

of three small army corps under Wright (VI.), Emory (XIX.)

and Crook (VIII.) and Torbert's cavalry (6000) in three divisions

under Averell, Merritt and Wilson, the whole numbering 30,000

infantry, 6000 cavalry and 27 batteries. Early continued to

hold Winchester with four divisions under Rodes, Gordon,

Breckinridge and Ramseur and two cavalry divisions under

Fitz Lee and Lomax. He had soon been deprived of Anderson's

corps which was sorely needed at Richmond, a fact which

Sheridan discovered through his spies in Winchester, and indeed

Sheridan had been waiting a fortnight for this movement by

which Early's command was to be reduced. For a month the

two armies had manoeuvred between Halltown and Strasburg,

each commander hoping for such an increase to his own or decrease

of his enemy's numbers as would justify attack. The Valley

operations were aided indirectly by assaults and sorties about

Petersburg. Grant aimed at preventing Lee sending reinforcements

to Early until Sheridan's plans had been carried out.

Meanwhile Early had been gathering up the harvests in the

lower Valley, but on the 20th of August Sheridan was able to

report “ I have destroyed everything that was eatable south of

Winchester, and they will have to haul supplies from well up

to Staunton.” Sheridan in September could put 23,000 infantry

and 8000 cavalry into action, and at this moment he was visited

by Grant, who encouraged his subordinate to seize an opportunity

to attack the enemy.

The first encounter of Sheridan and Early took place on the

19th of September about 2 m. east of Winchester. Sheridan

had crossed the Opequon and found the enemy in position

Win-

chester. astride the Winchester-Berryville road. Early was outnumbered and outfought, but he attributed his defeat to

the enemy's “ immense superiority in cavalry,” and in

fact Sheridan depicts Merritt's division as charging with sabre

or pistol in hand and literally riding down a hostile battery,

taking 1200 prisoners and 5 guns. The Federal victory,

however, cost Sheridan 4500 casualties and he had hoped for

greater success, since Early had divided his forces. Sheridan's

plan was to overwhelm Ramseur before he could be supported

by Rodes and Gordon, but Early contrived to bring these

divisions up and counter-attack while Sheridan was engaged

with Ramseur. Early had connded his left to Fitz Lee's cavalry

and taken Breckinridge to strengthen his right. But Merritt's

horsemen rode through the Confederate cavalry, who fled,

communicating their panic to the infantry of the left wing,

Fisher's

Hill.

and the day was lost. Early retreated through

Newtown and Strasburg, but at Fisher's Hill behind

Tumbling Run, where the Valley was entrenched on

a front of 3 m. between the Shenandoah river and Little North

Mountain, Early rallied his forces and again detailed his cavalry

to protect his left from a turning movement. But Sheridan

repeated his manoeuvre, and again on the 22nd of September

Early was attacked and routed, General Crook's column having

outflanked him by a détour on the western or Back road. Early

now retreated to Mount Jackson, checked the pursuit at Rode's

Hill, and, evading all Sheridan's efforts to bring him again to

battle, reached Port Republic on the 25th of September. On

learning of this disaster, and the distress of his troops, General

Lee promised to send him boots, arms and ammunition, but

under pressure of Grant's army, he could not spare any troops.

Lee had estimated Sheridan's force at 12,000 effective infantry,

and Early's report as to his being outnumbered by three or

four to one was not credited. Yet Early had much to do to

avoid destruction, for Sheridan had planned to cut off Early

by moving his cavalry up the Luray Valley to Newmarket

while the infantry held him at Fisher's Hill; but Torbert

with the cavalry blundered. Sheridan made Harrisonburg

his headquarters on the 25th of September, where he relieved

Averell of his command for having failed to pursue after the

battle of Fisher's Hill. In the first week of October Sheridan

held a line, across the Valley from Port Republic along North

river to the Back road, and his cavalry had advanced to Waynesboro

to destroy the railroad bridge there, to drive off cattle,

and burn the mills and all forage and bread stuffs. Early had

taken refuge in Blue Ridge at Rockfish Gap, where he awaited

Rosser's cavalry and KershaW's division (Longstreet's corps),

for Lee had resolved upon again reinforcing the Valley command,

and upon their arrival Early advanced to Mount Crawford and

thence to Newmarket. The Federals retired before him, but

his cavalry was soon to suffer another repulse, for Rosser and

Lomax having followed up Sheridan closely on the 9th of

October with five brigades, the Federal cavalry under Torbert

turned upon this body when it reached Tom's Brook (Fisher's

Hill) and routed it. Sheridan burnt the bridges behind him

as he retired on Winchester, and apparently trusted that Early

would trouble him no more and then he would rejoin Grant at

Petersburg. But Early determined to go north again, though

he had to rely upon Augusta county, south of Harrisonburg,

for supplies, for Sheridan had wasted Rockingham and Shenandoah

counties in accordance with Grant's order. The Union

commander-in-chief, contemplating a longer struggle between

the main armies than he had at first reckoned on, had determined

that the devastation of the Valley should be thorough

and lasting in its effect.

Sheridan at Winchester was now free to detach troops to aid Grant, or remain quiescent covering the Ohio railroad, or move east of Blue Ridge. He had resisted the demand of the government, which Grant had endorsed, that Early should be driven through the Blue Ridge back on Richmond. Sheridan pointed out that guerrilla forces were always in his rear, that he would need to reopen the Alexandria railroad as a line of supply, that he must detach forces to hold the Valley and protect the railroads, and that on nearing Richmond he might be attacked by a column sent out by Lee to aid Early. Yet in fact Sheridan carried out the government programme at the beginning of 1865, and therefore we may assume that his objections in October were not well-founded. Then he was expected to drive Early out of the Valley, but halted at Harrisonburg and, although in superior force, afterwards retired to Winchester, and his boast of having Wasted the Valley seemed ill-timed, since Early was able to follow him down to Strasburg. There was evidently some factor in the case which is not disclosed by Sheridan in his Memoirs.

Early at Newmarket on the 9th of October said that he could

depend on only 6000 muskets if he detached Kershaw, andCedar

Creek.

he had discovered that all positions in the Valley

could be turned, that the open country favoured the

shock tactics of the Federal cavalry, and so placed

his own cavalry at a disadvantage, who, he declared, could not

by dismounted action withstand attacks by superior numbers

with the arme blanche. In these circumstances it would appear

that Early showed great enterprise in following Sheridan down

to Strasburg on the 13th of October “ to thwart his purposes

if he should contemplate moving across the Ridge or sending

troops to Grant.” But as his forward position at Fisher's Hill

could not be long maintained for want of forage, he resolved

to attack Sheridan, and on the night of the 18th of October he

sent three divisions under Gordon to gain the enemy's rear,

while Kershaw's division attacked his left and Wharton's division

and the artillery engaged him in front. The attack was timed

to commence at 5 A.M. on the 19th of October, when Rosser's

cavalry was to engage Sheridan's cavalry and that of Lomax

was to close the Luray Valley. This somewhat complicated

disposition of forces was entirely successful, and Early counted

his gains as 1300 prisoners and 18 guns after routing the Federal

corps VIII. and XIX. and causing Wright's corps (VI.) to retire.

Yet before nightfall Early's force was in turn routed and he lost

23 guns. Early's report is that of a disheartened general.

He complains that his troops took to plundering, that his regimental

officers were incapable; and it is always the Federal

cavalry that cause panic by threatening to charge; he has to

confess that with a whole day before him he could neither complete

his victory nor take up a position for defence, nor even

retreat in good order with the spoils of battle. Sheridan had,

it seems, actually put Wright's corps in march for Petersburg

when news of Early's advance down the Valley reached him;

then he recalled Wright and on the 14th of October was holding

a defensive line along the north bank of Cedar Creek west of the

Valley pike about Middleton. Early had reconnoitred and

withdrawn as far as Fisher's Hill near Strasburg. Sheridan

at this juncture was called to Washington to consult Halleck,

the “ chief of staff,” on the 16th of October in reference to his

future movements: for Halleck claimed to control Sheridan and

often modified Grant's instructions to his subordinate. Before

Sheridan could rejoin his army on the 19th of October Early

had attacked and routed it, but Sheridan met the fugitives and

rallied them with the cry: “ We must face the other way.”

He found Getty's division and the cavalry acting as rear-guard,

and resolved to attack as soon as his troops could be reorganized.

Sheridan was, however, disturbed by reports of Longstreet's

coming by the Front Royal road to cut him off at Winchester,

and hesitated for some hours; but at 4 p.m. he attacked and

drove back the Confederates and so recovered all the ground

lost in the morning, and recaptured his abandoned guns and

baggage.

After the battle of Cedar Creek, Early again retreated south to Newmarket and Sheridan was in no condition to pursue. The Federal government had agreed to Sheridan's proposal to fortify a defensive line at Kernstown and hold it with a detachment while Sheridan rejoined Grant with the main body. On the 11th of November, Early again advanced to reconnoitre at Cedar Creek, but was driven back to Newmarket. At the beginning of December the weather threatened to interfere with movement and both sides began to send back troops to Petersburg. During the winter there were only cavalry raids and guerrilla warfare, and in February 1865 the infantry remaining on each side was less than a strong division. Sheridan seized the opportunity to advance with 10,000 cavalry. Early delayed this advance with his cavalry, while he evacuated Staunton; he called up a brigade to defend Lynchburg and proceeded to Waynesboro to await developments. Sheridan feared to advance on Lynchburg leaving Early on his flank and decided to attack Early at Waynesboro; and on the and of March the Federal commander was rewarded by decisive victory, capturing 1600 Confederates and their baggage and artillery. Early himself escaped and Rosser's cavalry dispersed to their homes in the Valley, but with Early's third defeat all organized resistance in the Shenandoah Valley came to an end. Sheridan moved over Blue Ridge to Charlottesville and began his work of destruction south and east. Lynchburg was too strongly held to be captured, but from Amherst Court House the railway to Charlottesville and the canal to Richmond were destroyed, and thus Lee's army was deprived of these arteries of supply. On the 10th of March at Columbia, on the James river south of Charlottesville, Sheridan sent couriers to advise Grant of his success, and on the 19th of March he rejoined the main army in Eastern Virginia, receiving Grant's warm commendation for having “ voluntarily deprived himself of independence.” (G. W. R.)