1911 Encyclopædia Britannica/Surveying

SURVEYING, the technical term for the art of determining the position of prominent points and other objects on the surface of the ground, for the purpose of making therefrom a graphic representation of the area surveyed. The general principles on which surveys are conducted and maps computed from such data are in all instances the same; certain measures are made on the ground, and corresponding measures are protracted on paper on whatever scale may be a convenient fraction of the natural scale. The method of surveying varies with the magnitude of the survey, which may embrace an empire or represent a small plot of land. All surveys rest primarily on linear measurements for the direct determination of distances; but linear measurement is often supplemented by angular measurement which enables distances to be determined by principles of geometry over areas which cannot be conveniently measured directly, such, for instance, as hilly or broken ground. The nature of the survey depends on the proportion which the linear and angular measures bear to one another and is almost always a combination of both.

History.—The art of surveying, i.e. the primary art of map- making from linear measurements, has no historical beginning. The first rude attempts at the representation of natural and artificial features on a ground plan based on actual measurements of which any record is obtainable were those of the Romans, who certainly made use of an instrument not unlike the plane-table for determining the alignment of their roads. Instruments adapted to surveying purposes were in use many centuries earlier than the Roman period. The Greeks used a form of log line for recording the distances run from point to point along the coast whilst making their slow voyage from the Indus to the Persian Gulf three centuries B.C.; and it is improbable that the adaptation of this form of linear measurement was confined to the sea alone. Still earlier (as early as 1600 B.C.) it is said that the Chinese knew the value of the loadstone and possessed some form of magnetic compass. But there is no record of their methods of linear measurements, or that the distances and angles measured were applied to the purpose of map-making (see Compass and Map). The earliest maps of which we have any record were based on inaccurate astronomical determinations, and it was not till medieval times, when the Arabs made use of the Astrolabe (q.v.), that nautical surveying (the earliest form of the art) could really be said to begin. In 1450 the Arabs were acquainted with the use of the compass, and could make charts of the coast-line of those countries which they visited. In 1498 Vasco da Gama saw a chart of the coast-line of India, which was shown him by a Gujarati, and there can be little doubt that he benefited largely by information obtained from charts which were of the nature of practical coast surveys. The beginning of land surveying (apart from small plan-making) was probably coincident with the earliest attempts to discover the size and figure of the earth by means of exact measurements, i.e. with the inauguration of geodesy (see Geodesy and Earth, Figure of the), which is the fundamental basis of all scientific surveying.

Classification.—For convenience of reference surveying may be considered under the following heads—involving very distinct branches of the art dependent on different methods and instruments[1]:—

| 1. Geodetic triangulation. | 4. Geographical surveys. |

| 2. Levelling. | 5. Traversing, and fiscal or revenue surveys. |

| 3. Topographical surveys. | 6. Nautical surveys. |

1. Geodetic Triangulation

Geodesy, as an abstract science dealing primarily with the dimensions and figure of the earth, may be found fully discussed in the articles Geodesy and Earth, Figure of the; but, as furnishing the basis for the construction of the first framework of triangulation on which all further surveys depend (which may be described as its second but most important function), geodesy is an integral part of the art of surveying, and its relation to subsequent processes requires separate consideration. The part which geodetic triangulation plays in the general surveys of civilized countries which require closely accurate and various forms of mapping to illustrate their physical features for military, political or fiscal purposes is best exemplified by reference to some completed system which has already served its purpose over a large area. That of India will serve as an example.

The great triangulation of India was, at its inception, calculated to satisfy the requirements of geodesy as well as geography, because the latitudes and longitudes of the points of the triangulation had to be determined for future reference by process of calculation combining the results of the triangulation with the elements of the earth’s figure. The latter were not then known with much accuracy, for so far geodetic operations had been mainly carried on in Europe, and additional operations nearer the equator were much wanted; the survey was conducted with a view to supply this want. Thus high accuracy was aimed at from the first.

Primarily a network was thrown over the southern peninsula. The triangles on the central meridian were measured with extra care and checked by base-lines at distances of about 2° apart in latitude in order to form a geodetic arc, with the addition of astronomically determined latitudes at certain of the stations. The base-lines were measured with chains and the principal angles with a 3-ft. theodolite. The signals were cairns of stones or poles. The chains were somewhat rude and their units of length had not been determined originally, and could not be afterwards ascertained. The results were good of their kind and sufficient for geographical purposes; but the central meridional arc—the “great arc”—was eventually deemed inadequate for geodetic requirements. A superior instrumental equipment was introduced, with an improved

Trigonometrical Survey of India.

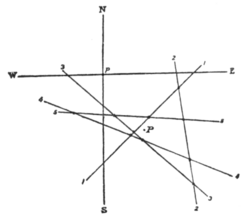

Fig. 1.

modus operandi, under the direction of Colonel Sir G. Everest in 1832. The network system of triangulation was superseded by meridional and longitudinal chains taking the form of gridirons and resting on base-lines at the angles of the gridirons, as represented in fig. 1. For convenience of reduction and nomenclature the triangulation west of meridian 92° E. has been divided into five sections—the lowest a trigon, the other four quadrilaterals distinguished by cardinal points which have reference to an observatory in Central India, the adopted origin of latitudes. In the north-east quadrilateral, which was first measured, the meridional chains are about one degree apart; this distance was latterly much increased and eventually certain chains—as on the Malabar coast and on meridian 84° in the south-east quadrilateral—were dispensed with because good secondary triangulation for topography had been accomplished before they could be begun.

All base-lines were measured with the Colby apparatus of compensation bars and microscopes. The bars, 10 ft. long, were set up horizontally on tripod stands; the microscopes, 6 in. apart, were mounted in pairs revolving round a vertical axis and were set up on tribrachs fitted to the ends of the bars. Six bars and five central and two end pairs of microscopes—the latter with their vertical axes perforated for a look-down telescope—constituted a complete apparatus, measuring 63 ft. between the ground pins or registers. Compound bars are more liable to accidental changes of length than simple bars; they were therefore tested from time to time by comparison with a standard simple bar; the microscopes were also tested by comparison with a standard 6-in. scale. At the first base-line the compensated bars were found to be liable to sensible variations of length with the diurnal variations of temperature; these were supposed to be due to the different thermal conductivities of the brass and the iron components. It became necessary, therefore, to determine the mean daily length of the bars precisely, for which reason they were systematically compared with the standard before and after, and sometimes at the middle of, the base-line measurement throughout the entire day for a space of three days, and under conditions as nearly similar as possible to those obtaining during the measurement. Eventually thermometers were applied experimentally to both components of a compound bar, when it was found that the diurnal variations in length were principally due to. difference of position relatively to the sun, not to difference of conductivity—the component nearest the sun acquiring heat most rapidly or parting with il most slowly, notwithstanding that both were in the same box, which was always sheltered from the sun's rays. Happily the systematic comparisons of the compound bars with the standard were found to give a sufficiently exact determination of the mean daily length. An elaborate investigation of theoretical probable errors (p.e.) at the Cape Comorin base snowed that, for any base-line measured as usual without thermometers in the compound bars, the p.e. may be taken as ±1·5 millionth parts of the length, excluding unascertainable constant errors, and that on introducing thermometers into these bars the p.e. was diminished to ± 0·55 millionths.

In all base-line measurements the weak point is the determination of the temperature of the bars when that of the atmosphere is rapidly rising or falling; the thermometers acquire and lose heat more rapidly than the bar if their bulbs are outside, and more slowly if inside the bar. Thus there is always more or less lagging, and its effects are only_ eliminated when the rises and falls are of equal amount and duration; but as a rule the rise generally predominates greatly during the usual hours of work, and whenever this happens lagging may cause more error in a base-line measured with simple bars than all other sources of error combined. In India the probable average lagging of the standard-bar thermometer was estimated as not less than 0-3° F., corresponding to an error of—2 millionths in the length of a base-line measured with iron bars. With compound bars lagging would be much the same for both components and its influence would consequently be eliminated. Thus the most perfect base-line apparatus would seem to be one of compensation bars with thermometers attached to each component; then the comparisons with the standard need only be taken at the times when the temperature is constant, and there is no lagging.

The plan of triangulation was broadly a system of internal meridional and longitudinal chains with an external border of oblique chains following the course of the frontier and the coast lines. The design of each chain was necessarily much influenced by the physical features of the country over which it was carried. The most difficult tracts were plains, devoid of any commanding points of view, in some parts covered with forest and jungle, malarious and almost uninhabited, in other parts covered with towns and villages and umbrageous trees. In such tracts triangulation was impossible except by constructing towers as stations of observation, raising them to a sufficient height to overtop at least the earth's curvature, and then either increasing the height to surmount all obstacles to mutual vision, or clearing the lines. Thus in hilly and open country the chains of triangles were generally made " double " throughout, i.e. formed of polygonal and quadrilateral figures to give greater breadth and accuracy; but in forest and close country they were carried out as series of single triangles, to give a minimum of labour and expense. Symmetry was secured by restricting the angles between the limits of 30° and: 90 °. The average side length was 30 m. in hill country and 11 in the plains; the longest principal side was 62·7 m., though in the secondary triangulation to the Himalayan peaks there were sides exceeding 200 m. Long sides were at first considered desirable, on the principle that the fewer the links the greater the accuracy of a chain of triangles; but it was eventually found that good observations on long sides could only be obtained under exceptionally favourable atmospheric conditions. In plains the length was governed by the height to which towers could be conveniently raised to surmount the curvature, under the well-known condition, height in feet = 2/3 × square of the distance in miles; thus 24 ft. of height was needed at each end of a side to overtop the curvature in 12 m., and to this had to be added whatever was required to surmount obstacles on the ground. In Indian plains refraction is more frequently negative than positive during sunshine; no reduction could therefore be made for it.

The selection of sites for stations, a simple matter in hills and open country, is often difficult in plains and close country. In the early operations, when the great arc was being carried across the wide plains of the Gangetic valley, which are covered with villages and trees and other obstacles to distant vision, masts 35 ft. high were carried about for the support of the small reconnoitring theodolites, with a sufficiency of poles and bamboos to form a scaffolding of the same height for the observer. Other masts 70 ft. high, with arrangements for displaying blue lights by night at 90 ft., were erected at the spots where station sites were wanted. But the cost of transport was great, the rate of progress was slow, and the results were unsatisfactory. Eventually a method of touch rather than sight was adopted, feeling the ground to search for the obstacles to be avoided, rather than attempting to look over them: the “rays” were traced either by a minor triangulation, or by a traverse with theodolite and perambulator, or by a simple alignment of flags. The first method gives the direction of the new station most accurately; the second searches the ground most closely; the third is best suited for tracts of uninhabited forest in which there is no choice of either line or site, and the required station may be built at the intersection of the two trial rays leading up to it. As a rule it has been found most economical and expeditious to raise the towers only to the height necessary for surmounting the curvature, and to remove the trees and other obstacles on the lines.

Each principal station has a central masonry pillar, circular and 3 to 4 ft. in diameter, for the support of a large theodolite, and around it a platform 14 to 16 ft. square for the observatory tent, observer and signallers. The pillar is 1 , isolated from the platform, and when solid carries the station mark—a dot surrounded by a circle—engraved on a stone at its surface, and on additional stones or the rock in situ, in the normal of the upper mark; but, if the height is considerable and there is a liability to deflection, the pillar is constructed with a central vertical shaft to enable the theodolite to be plumbed over the ground-level mark, to which access is obtained through a passage in the basement. In early years this precaution against deflection was neglected and the pillars were built solid throughout, whatever their height; the surrounding platforms, being usually constructed of sun-dried bricks or stones and earth, were liable to fall and press against the pillars, some of which thus became deflected during the rainy seasons that inter- vened between the periods during which operations were arrested or the beginning and close of the successive circuits of triangles. Large theodolites were invariably employed. Repeating circles were highly thought of by French geodesists at the time when the operations in India were begun ; but they were not used in the survey, and have now been generally discarded. The principal theodolites were somewhat similar to the astronomer's alt-azimuth instrument, but with larger azimuthal and smaller vertical circles, also with a greater base to give the firmness and stability which are required in measuring horizontal angles. The azimuthal circles had mostly diameters of either 36 or 24 in., the vertical circles having a diameter of 18 in. In all the theodolites the base was a tribrach resting on three levelling foot-screws, and the circles are read by microscopes; but in different instruments the fixed and the rotatory parts of the body varied. In some the vertical axis was fixed on the tribrach and projected upwards; in others it revolved in the tribrach and projected downwards. In the former the azimuthal circle was fixed to the tribrach, while the telescope pillars, the microscopes, the clamps and the tangent screws were attached to a drum revolving round the vertical axis; in the latter the microscopes, clamps and tangent screws were fixed to the tribrach, while the telescope pillars and the azimuthal circle were attached to a plate fixed at the head of the rotary vertical axis.

Cairns of stones, poles or other opaque signals were primarily employed, the angles being measured by day only; eventually it was found that the atmosphere was often more favourable for observing by night than by day, and that distant points were raised well into view by refraction by night which might be invisible or only seen with difficulty by day. Lamps were then introduced of the simple form of a cup, 6 in. in diameter, filled with cotton seeds steeped in oil and resin, to burn under an inverted earthen jar, 30 in. in diameter, with an aperture in the side towards the ob- server. Subsequently this contrivance gave place to the Argand lamp with parabolic reflector; the opaque day signals were discarded for heliotropes reflecting the sun's rays to the observer. The introduction of luminous signals not only rendered the night as well as the day available for the observations but changed the char- acter of the operations, enabling work to be done during the dry and healthy season of the year, when the atmosphere is generally hazy and dust-laden, instead of being restricted as formerly to the rainy and unhealthy seasons, when distant opaque objects are best seen. A higher degree of accuracy was also secured, for the luminous signals were invariably displayed through diaphragms of appropriate aperture, truly centred over the station mark; and, looking like stars, they could be observed with greater precision, whereas opaque signals are always dim in comparison and are liable to be seen excentncally when the light falls on one side. A signalling party of three men was usually found sufficient to manipulate a pair of heliotropes—one for single, two for double reflection, according to the sun's position — and a lamp, throughout the night and day. Heliotropers were also employed at the observing stations to flash instructions to the signallers.

The theodolites were invariably set up under tents for protection against sun, wind and rain, and centred, levelled and adjusted for the runs of the microscopes. Then the signals were observed in regular rotation round the horizon, alternately from right to left and vice versa; after the prescribed minimum number of rounds, either two or three, Measuring Horizontal Angles. had been thus measured, the telescope was turned through 180° both in altitude and azimuth, changing the position of the face of the vertical circle relatively to the observer, and further rounds were measured; additional measures of single angles were taken if the prescribed observations were not sufficiently accordant. As the microscopes were invariably equidistant and their number was always odd, either three or five, the readings taken on the azimuthal circle during the telescope pointings to any object in the two positions of the vertical circle, “face right” and “face left,” were made on twice as many equidistant graduations as the number of microscopes. The theodolite was then shifted bodily in azimuth, by being turned on the ring on the head of the stand, which brought new graduations under the microscopes at the telescope pointings; then further rounds were measured in the new positions, face right and face left. This process was repeated as often as had been previously prescribed, the successive angular shifts of position being made by equal arcs bringing equidistant graduations under the microscopes during the successive telescope pointings to one and the same object. By these arrangements all periodic errors of graduation were eliminated, the numerous graduations that were read tended to cancel accidental errors of division, and the numerous rounds of measures to minimize the errors of observation arising from atmospheric and personal causes.

Under this system of procedure the instrumental and ordinary errors are practically cancelled and any remaining error is most probably due to lateral refraction, more especially when the rays of light graze the surface of the ground. The three angles of every triangle were always measured.

The apparent altitude of a distant point is liable to considerable variations during the twenty-four hours, under the influence of changes in the density of the lower strata of the atmosphere. Terrestrial refraction is capricious, more particularly when the rays of light graze the surface of the ground, passing through a medium which is liable to extremes of rarefaction and condensation, under the alternate influence of the sun's heat radiated from the surface of the ground and of chilled atmospheric vapour. When the back and forward verticals at a pair of stations are equally refracted, their difference gives an exact measure of the difference of height. But the atmospheric conditions are not always identical at the same moment everywhere on long rays which graze the surface of the ground, and the ray between two reciprocating stations is liable to be differently refracted at its extremities, each end being influenced in a greater degree by the conditions prevailing around it than by those at a distance; thus instances are on record of a station A being invisible from another B, while B was visible from A.

When the great arc entered the plains of the Gangetic valley, simultaneous reciprocal verticals were at first adopted with the hope of eliminating refraction ; but it was soon found that they did not do so sufficiently to justify the expense of the additional instruments and observers. Afterwards the back and forward verticals were observed as the stations were Refraction. visited in succession, the back angles at as nearly as possible the same time of the day as the forward angles, and always during the so-called " time of minimum refraction," which ordinarily begins about an hour after apparent noon and lasts from two to three hours. The apparent zenith distance is always greatest then, but the refraction is a minimum only at stations which are well elevated above the surface of the ground ; at stations on plains the refraction is liable to pass through zero and attain a considerable negative magnitude during the heat of the day, for the lower strata of the atmosphere are then less dense than the strata immediately above and the rays are refracted downwards. On plains the greatest positive refractions are also obtained—maximum values, both positive and negative, usually occurring, the former by night, the latter by day, when the sky is most free from clouds. The values actually met with were found to range from +1·21 down to −0·09 parts of the contained arc on plains; the normal “coefficient of refraction” for free rays between hill stations below 6000 ft. was about 0·07, which diminished to 0·04 above 18,000 ft., broadly varying inversely as the temperature and directly as the pressure, but much influenced also by local climatic conditions.

In measuring the vertical angles with the great theodolites, graduation errors were regarded as insignificant compared with errors arising from uncertain refraction; thus no arrangement was made for effecting changes of zero in the circle settings. The observations were always taken in pairs, face right and left, to eliminate index errors, only a few daily, but some on as many days as possible, for the variations from day to day were found to be greater than the diurnal variations during the hours of minimum refraction.

In the ordnance and other surveys the bearings of the surrounding stations are deduced from the actual observations, but from the “included angles” in the Indian survey. The observations of every angle are tabulated vertically in as many columns as the number of circle settings face left and face right, and the mean for each setting is taken. For several years the general mean of these was adopted as the final result; but subsequently a " concluded angle " was obtained by combining the single means with weights inversely proportional to g2 + o2 ÷ n—g, being a value of the e.m.s.[2] of graduation derived empirically from the differences between the general mean and the mean for each setting, o the e.m.s. of observation deduced from the differences between the individual measures and their respective means, and n the number of measures at each setting. Thus, putting mi, wi, . . . for the weights of the single means, w for the weight of the concluded angle, M for the general mean, C for the concluded angle, and d1, d2, . . . for the differences between M and the single means, we have

| C=M + w1d1 + w2d2 +/w1 + w2 + | (1) |

C — M vanishes when n is constant ; it is inappreciable when g is much larger than o; it is significant only when the graduation errors are more minute than the errors of observation; but it was always small, not exceeding 0·14″ with the system of two rounds of measures and 0·05″ with the system of three rounds.

The weights of the concluded angles thus obtained were employed in the primary reductions of the angles of single triangles and polygons which were made to satisfy the geometrical conditions of each figure, because they were strictly relative for all angles measured with the same instrument and under similar circumstances and conditions, as was almost always the case for each single figure. But in the final reductions, when numerous chains of triangles composed of figures executed with different instruments and under different circumstances came to be adjusted simultaneously, it was necessary to modify the original weights, on such evidence of the precision of the angles as might be obtained from other and more reliable sources than the actual measures of the angles. This treatment will now be described.

Values of theoretical error for groups of angles measured with the same instrument and under similar conditions may be obtained in three ways—(i.) from the squares of the reciprocals Theoretical of the weight w deduced as above from the measures of such angle, (ii.) from the magnitudes of the excess of the sum of the angles of each triangle above 180°+ the, spherical excess, and (iii.) from the magnitudes of the corrections which it is necessary to apply to the angles of polygonal figures and networks to satisfy the several geometrical conditions.

Every figure, whether a single triangle or a polygonal network, was made consistent by the application of corrections to the observed angles to satisfy its geometrical conditions. The three angles of every triangle having been observed, their sum had to be made = 180° + the spherical excess; in networks it was also necessary that the sum of the angles measured round the horizon at any station should be exactly = 360°, that the sum of the parts of an angle measured at different times should equal the whole and that the ratio of any two sides should be identical, whatever the route through which it was computed. These are called the triangular, central, toto-partial and side conditions; they present n geometrical equations, which contain t unknown quantities, the errors of the observed angles, t being always > n. When these equations are satisfied and the deduced values of errors are applied as corrections to the observed angles, the figure becomes consistent. Primarily the equations were treated by a method of successive approximations; but afterwards they were all solved simultaneously by the so-called method of minimum squares, which leads to the most probable of any system of correc- tions.

The angles having been made geometrically consistent inter se in each figure, the side-lengths are computed from the base-line onwards by Legendre's theorem, each angle being dimin- i>ldes or j shed by one _third of the spherical excess of the triangle mangles. tQ wh; cJ) j t appertains. The theorem is applicable without sensible error to triangles of a much larger "size than any that are ever measured.

A station of origin being chosen of which the latitude and longitude are known astronomically, and also the azimuth of one of the Latitude and surrounding stations, the differences of latitude and £,on£«'u<feo/longitude and the reverse azimuths are calculated in Stations; succession, for all the stations of the triangulation, Azimuth of by Puissant's formulae (Traite de giodesie, 3rd ed., Paris, Sides. 1842).

Problem. — Assuming the earth to be spheroidal, let A and B be two stations on its surface, and let the latitude and longitude of A be known, also the azimuth of B at A, and the distance between A and B at the mean sea-level; we have to find the latitude and longitude of B and the azimuth of A at B.

The following symbols are employed: a the major and 6 the

minor semi-axis; e the excentricity, = j — -p — [; p the radius of curvature to the meridian in latitude X, = 1 1— e 2 sin 2 Xil ' " t ' le norrna '

to the meridian in latitude X, = 1 j_ e 2 sm 2xlj' ^ anc ^ ^ the S' ven

latitude and longitude of A; X + AX and L + &L the required latitude and longitude of B; A the azimuth of B at A; B the azimuth of A at B; ∆A =B — (π+A); c the distance between AandB. Then, all azimuths being measured from the south, we have

cos A cosec

sinM. tan X coscc 1"

cosM sin 2X cosec 1"

4 p.v 1 — e 1

+g , sinM cos A(l+3 tan'X) cosec 1'

Ai" =

v cos X

cosec 1

1 c 1 sin 2j4 tan X .

+- -. — — -r cosec r

2 ** cos X

1 c* ( 1 +3 tan'X) sin 2A cosA ~6 v* cos X . I C* sinM tan 5 X .

+:,-! r - ^ cosec 1

3 v* cos X

cosec 1

(3)

f(4)

A/l"or

B-(TT+A):

— sin A tan X coscc 1" v

, I c 2 \ , ... e'cos'X ) . . ,

+tt j 1+2 tan 2 X-| — - a \ sin 2/lcosec 1

— -jfg+tan'X J — - — sin 2A cos/1 coscc 1"

+|-jsinM tan X (1+2 tan'X) cosec 1" H5 (5)

Each A is the sum of four terms symbolized by S\, 8», it and S t; the calculations arc so arranged as to produce these terms in the order S\, 6L, and SA, each term entering as a factor in calculating the following term. The arrangement is shown below in equations in which the symbols P, Q, . . . Z represent the factors which depend on the adopted geodetic constants, and vary with the latitude; the logarithms of their numerical values are tabulated in the Auxiliary Tables to Facilitate the Calculations of the Indian Survey. S 1 \ = —P.cosA.c 6iL=-HiX.Q.secX.taa4 SiA = +SiL.sin\]

«,X=+M. R.sinA.c S 1 L = -S,\.S. cot A M = +«ii.r \ (t ~,

6 s \=-i,A.V. cotA «ji = +« 3 X . Z/.sin/l x i*A = +«»i . W [ w

«,X = -«jA.X.tanA SiL = +S t \. Y.tanA &A = +««£,. Z J

The calculations described so far suffice to make the angles of the several trigonometrical figures consistent inter se, and to give preliminary values of the lengths and azimuths of the sides and the latitudes and longitudes of the stations. The results are amply sufficient for the requirements of the topographer and land surveyor, and they are published in preliminary charts, which give full numerical " on ' details of latitude, longitude, azimuth and side-length, and of height also, for each portion of the triangulation — secondary as well as principal — as executed year by year. But on the completion of the several chains of triangles further reductions became necessary, to make the triangulation everywhere consistent inter se and with the verificatory base-lines, so that the lengths and azimuths of common sides and the latitudes and longitudes of common stations should be identical at the junctions of chains and that the measured and computed lengths of the base-lines should also be identical.

As an illustration of the problem for treatment, suppose a combination of three meridional and two longitudinal chains comprising seventy-two single triangles with a base-line at each corner as

shown in the accompanying C B

Fig. 2.

diagram (fig. 2); suppose the three angles of every triangle to have been measured and made. consistent. Let A be the origin, with its latitude and longitude given, and also the length and azimuth of the adjoining base-line. With these data processes of calculation are carried through D the triangulation to obtain the _

lengths and azimuths of the fig. 2.

sides and the latitudes and longitudes of the stations, say in the following order: from A through B to E, through F to E, through F to D, through F and E to C, and through F and D to C. Then there are two values of side, azimuth, latitude and longitude at E — one from the right-hand chains via B, the other from the left-hand chains via F; similarly there are two sets of values at C; and each of the base-lines at B, C and D has a calculated as well as a measured value. Thus eleven absolute errors are presented for dispersion over the triangulation by the application _ of the most appropriate correction to each angle, and, as a preliminary to the determination of these corrections, equations must be constructed between each of the absolute errors and the unknown errors of the angles from which they originated. For this purpose assume X to be the angle opposite the flank side of any triangle, and Y and Z the angles opposite the sides of continuation; also let x, y and s be the most probable values of the errors of the angles which will satisfy the given equations of condition. Then each equation may be expressed in the form [ax+by+cz] = E, the brackets indicating a summation for all the triangles involved. We have first to ascertain, the values of the coefficients o, 6 and c of the unknown quantities. They are readily found for the side equations on the circuits and between the base-lines, for x does not enter them, but only y and z, with coefficients which are the cotangents of YandZ, so that these equations are simply [cot Y.y— cot JZ.z]=E. But three out of four of the circuit equations are geodetic, corresponding to the closing errors in latitude, longitude and azimuth, and in them the coefficients are very complicated. They are obtained as follows. The first term of each of the three expressions for ∆X, ∆L, and B is differentiated in terms of c and A, giving

rf.AX = AX- \^-dA tan A sin 1″|

d.AL~ AL\ -j + dA cot A sin 1" |

dB=dA+AA \ ~+dA cot A sin 1" | (7) in which dc and dA represent the errors in the length and azimuth

Fig. 3.

of any side c which have been generated in the course of the triangulation up to it from the base-line and the azimuth station at the origin. The errors in the latitude and longitude of any station which are due to the triangulation are d\, = [d.A\], and dL, =\d.AL]. Let station I be the origin, and let 2, 3, ... be the succeeding stations taken along a predetermined line of traverse, which may either run from vertex to vertex of the successive triangles, zigzagging between the flanks of the chain, as in fig- 3 (1)1 or be carried directly along one of the flanks, as in fig. 3 (2). For the general symbols of the differential equa- tions substitute AX„, AL„, AA n , Cn, An, and Bn, for the side between stations n and n-J-i of the traverse; and let Sc n and SA n be the errors generated between the sides Cn_i and Cn ; then

dAi = SAi; dA i =dB 1 +&A 1 ; ... dA n =d3 n -.i+SA n . Performing the necessary substitutions and summations, we get

Ci ' 2 l ~'C2 ' "Cn

+ (l+"[M cot A] sin l'^Ai + d+^lAA cot A] sin i")SA 2

+ .. . +(i+Ai4»cot An sin i")SA n -

- [AX]f + >X]g+...+AA^

-|"[AX tan 4]&4i-r£[AX tan A]SA,+ . . . +&K, tan A n SAn) sin 1*

+|"[AL cot A]SAi+ n 2 [AL cot A]SA,+ . . . +ALn cot AnSAn] sin I*. Thus we have the following expression for any geodetic error: —

(8)

where 11 and <j> represent the respective summations which are the coefficients of Sc and SA in each instance but the first, in which I is added to the summation in forming the coefficient of SA .

The angular errors x, y and z must now be introduced, in place of Sc and SA, into the general expression, which will then take differ- ent forms, according as the route adopted for the line of traverse was the zigzag or the direct. In the former, the number of stations on the traverse is ordinarily the same as the number of triangles, and, whether or no, a common numerical notation may be adopted for both the traverse stations and the collateral triangles; thus the angular errors of every triangle enter the general expression in the form =*=</>*+coty./i'y— cot Z./x'z,

in which 1/ =/x sin 1 *, and the upper sign of tj> is taken if the triangle lies to the left, .the lower if to the right, of the line of traverse. When the direct traverse is adopted, there are only half as many traverse stations as triangles, and therefore only half the number of ix's and <t>'s to determine; but it becomes necessary to adopt different numberings for the stations and the triangles, and the form of the coefficients of the angular errors alternates in successive triangles. Thus, if the pth triangle has no side on the line of the traverse but only an angle at the /th station, the form is

+ <l>i.x p + cot Y„ . n\ . y„-cot Z p . nl . g,.

If the gth triangle has a side between the /th and the (/+l)th stations of the traverse, the form is

cot X,(n[ — /i'j+i)*, + (<#>i + ii't+i cot Y q )y q — (<t>i+i — nl cot Z„)z q .

As each circuit has a right-hand and a left-hand branch, the errors of the angles are finally arranged so as to present equations of the general form

[ax+by+cz] r — [ax+by+cz]i =E.

The eleven circuit and base-line equations of condition having been duly constructed, the next step is to find values of the angular errors which will satisfy these equations, and be the most probable of any system of values that will do so, and at the same time will not disturb the existing harmony of the angles in each of the seventy- two triangles. Harmony is maintained by introducing the equation of condition x+y+z=o for every triangle. The most probable results are obtained by the method of minimum squares, which may be applied in two ways.

i. A factor X may be obtained for each of the eighty-three equations under the condition that

[u ' V ' WJ

is made a minimum,

«, v and w being the reciprocals of the weights of the observed angles. This necessitates the simultaneous solution of eighty-three equations to obtain as many values of X. The resulting values of the errors of the angles in any, the pth, triangle, are

x r = u f [a v \] ; y p = v P [b p \] ; z p = w„[c„X]. (9)

ii. One of the unknown quantities in every triangle, as x, may be eliminated from each of the eleven circuit and base-line equa- tions by substituting its equivalent — (y+z) for it, a similar substi- tution being made in the minimum. Then the equations take the form [(&— a)y+(c— a)z]=E, while the minimum becomes

r (y+z)« . y* . zn

Thus we have now to find only eleven values of X by a simultaneous solution of as many equations, instead of eighty-three values from eighty-three equations; but we arrive at more complex expressions for the angular errors as follows : —

yr = Z^£f^\fo+Wr)l(h-<h)>]-w P Kc p -a I ,)\])\ Up ^l +w J i(^+ v p)[^p-a p )\]-v P l(.b p -a p ) (10)

The second method has invariably been adopted, originally be- cause it was supposed that, the number of the factors X being re- duced from the total number of equations to that of the circuit and base-line equations, a great saving of labour would be effected. But subsequently it was ascertained that in this respect there is little to choose between the two methods; for, when x is not eliminated, and as many factors are introduced as there are equations, the factors for the triangular equations may be readily eliminated at the outset. Then the really severe calculations will be restricted to the solution of the equations containing the factors for the circuit and base-line equations as in the second method.

In the preceding illustration it is assumed that the base-lines are errorless as compared with the triangulation. Strictly speaking, however, as base-lines are fallible quantities, presumably of differ- ent weight, their errors should be introduced as unknown quantities of which the most probable values are to be. determined in a simul- taneous investigation of the errors of all the facts of observation, whether linear or angular. When they are connected together by so few triangles that their ratios may be deduced as accurately, or nearly so, from the triangulation as from the measured lengths, this ought to be done; but, when the connecting triangles are so numerous that the direct ratios are of much greater weight than the trigonometrical, the errors of the base-lines may be neglected. In the reduction of the Indian triangulation it was decided, after examining the relative magnitudes of the probable errors of the linear and the angular measures and ratios, to assume the base-lines to be errorless.

The chains of triangles being largely composed of polygons or other networks, and not merely of single triangles, as has been assumed for simplicity in the illustration, the geometrical harmony to be maintained involved the introduction of a large number of " side," " central " and " toto-partial " equations of condition, as well as the triangular. Thus the problem for attack was the simul- taneous solution of a number of equations of condition = that of all the geometrical conditions of every figure +f our times the number of circuits formed by the chains of triangles +the number of base- lines— 1, the number of unknown quantities contained in the equations being that of the whole of the observed angles; the method of procedure, if rigorous, would be precisely similar to that already indicated for " harmonizing the angles of trigonometrical figures," of which it is merely an expansion from single figures to great groups.

The rigorous treatment would, however, have involved the simul- taneous_ solution of about 4000 equations between 9230 unknown quantities, _ which _ was impracticable. The triangulation was therefore divided into sections for separate reduction, of which the most important were_ the five between the meridians of 67 ° and 92 (see fig. 1), consisting of four quadrilateral figures and a trigon, each comprising several chains of triangles and some base- lines. This arrangement had the advantage of enabling the final reductions to be taken in hand as soon as convenient after the completion of any section, instead of being postponed until all were completed. It was subject, however, to the condition that the sections containing the best chains of triangles were to be first reduced; for, as all chains bordering contiguous sections would necessarily be " fixed " as a part of the section first reduced, it was obviously desirable to run no risk of impairing the best chains by forcing them into adjustment with others 01 inferior quality. It happened that both the north-east and the south-west quadrilaterals contained several of the older chains; their reduction was therefore made to follow that of the collateral sections containing the modern chains.

But the reduction of each of these great sections was in itself a very formidable undertaking, necessitating some departure from a purely rigorous treatment. For the chains were largely composed of polygonal networks and not of single triangles only as assumed in the illustration, and therefore cognizance had to be taken of a number of “side " and other geometrical equations of condition, which entered irregularly and caused great entanglement. Equations 9 and 10 of the illustration are of a simple form because they have a single geometrical condition to maintain, the triangular, which is not only expressed by the simple and symmetrical equation x+y+z=0, but—what is of much greater importance-recurs in a regular order of sequence that materially facilitates the general solution. Thus, though the calculations must in all cases be very numerous and laborious, rules can be formulated under which they can be well controlled at every stage and eventually brought to a successful issue. The other geometrical conditions of networks are expressed by equations which are not merely of a more complex form but have no regular order of sequence, for the networks present a variety of forms; thus their introduction would cause much entanglement and complication, and greatly increase the labour of the calculations and the chances of failure. Wherever, therefore, any compound figure occurred, only so much of it as was required to form a chain of single triangles was employed. The figure having previously been made consistent, it was immaterial what part was employed, but the selection was usually made so as to introduce the fewest triangles, The triangulation for final simultaneous reduction was thus made to consist of chains of single triangles only; but all the included angles were “fixed” simultaneously. The excluded angles of compound figures were subsequently harmonized with the fixed angles, which was readily done for each figure per se.

This departure from rigorous accuracy was not of material importance, for the angles of the compound figures excluded from the simultaneous reduction had already, in the course of the several independent figural adjustments, been made to exert their full in-Huence on the included angles. The figural adjustments had, however, introduced new relations between the angles of different figures, causing their weights to increase caeteris paribus with the number of geometrical conditions satisfied in each instance. Thus, suppose w to be the average weight of the t observed angles of any figure, and n the number of geometrical conditions presented for satisfaction; then the average weight of the angles after adjustment may be taken as w.t/t − n, the factor thus being 1.5 for a triangle, 1.8 for a hexagon, 2 for a quadrilateral, 2.5 for the network around the Sironj base-line, &c.

In framing the normal equations between the indeterminate factors A for the final simultaneous reduction, it would have greatly added to the labour of the subsequent calculations if a separate weight had been given to each angle, as was done in the primary figural reductions; this was obviously unnecessary, for theoretical requirements would now be amply satisfied by giving equal weights to all the angles of each independent figure. The mean weight that was finally adopted for the angles of each group was therefore taken as

w.ot/t − n

ρ being the modulus.

The second of the two processes for a plying the method of minimum squares having been adopted, the values of the errors y and z of the angles appertaining to any, the pth, triangle were finally expressed by the following equations, which are derived from (10) by substituting u for the reciprocal final mean weight as above determined:-

yr 3 '1§ Bl(2bP " ap "' 511)>l ()

II

Zp = 1§ 'il(25z1 ' ap " bP))l

The following table gives the number of equations of condition and unknown quantities-the angular errors-in the five great sections of the triangulation, which were respectively included in the simultaneous general reductions and relegated to the subsequent adjustments of each figure per se:—

Section. Simultaneous. External Figural.

Equations. Equations.

- 1. N.W. Quad.” C23 550 165b 267 104 152 6 761 110

- 2. S.E. Quad. 15 277 831 164 64 92 2 476 68

- 3. N.E. Quad. 49 573 1719 112 56 69 0 341 50

- 4. Trigon. . 22 303 909 192 79 101 2 547 77

- 5. S.W. Quad. 24 172 516 83 32 52 1 237 40

The corrections to the angles were generally minute, rarely exceeding the theoretical probable errors of the angles, and therefore applicable without taking any liberties with the facts of observation.

Azimuth observations in connexion with the principal triangulation were determined by measuring the horizontal angle between a referring mark and a circumpolar star, shortly before and after elongation, and usually at both elongations in order to eliminate the error of the star's place. SystematicAzimuth Observation. changes of “face” and of the zero settings of the azimuthal circle were made as in the measurement of the principal angles; but the repetitions on each zero were more numerous; the azimuthal levels were read and corrections applied to the star observations for dishevelment. The triangulation was not adjusted, in the course of the final simultaneous reduction, to the astronomically determined azimuths, because they are liable to be vitiated by local attractions; but the azimuths observed at about fifty stations around the primary azimuthal station, which was adopted as the origin of the geodetic calculations, were referred to that station, through the triangulation, for comparison with the primary azimuth. A table was prepared of the differences (observed at the origin computed from a distance) between the primary and the geodetic azimuths; the differences were assumed to be mainly due to the local reflexions of the plumb-line and only partially to error in the triangulation, and each was multiplied by the factor

p = tangent of latitude of origin,/tangent of latitude of comparing station

in order that the effect of the local attraction on the azimuth observed at the distant station-which varies with the latitude and is =the reflexion in the prime vertical X the tangent of the latitude—might be converted to what it would have been had the station been situated in the same latitude as the origin. Each deduction was given a weight, w, inversely proportional to the number of triangles connecting the station with the origin, and the most probable value of the error of the observed azimuth at the origin was taken as

| x = [(observed−computed) p w]/[w] | (12}; |

the value of x thus obtained was −1.1″.

The formulae employed in the reduction of the azimuth observations were as follows. In the spherical' triangle PZS, in which P is the pole, Z the zenith and S the star, the co-latitude PZ and the polar distance PS are known, and, as the angle at S is a ri ht angle at the elongation, the hour angle and the azimuth at that time are found from the equations,

cosP = tanPScotPZ,

cosZ = cosPSsinP.

The interval, δP, between the time of any observation and that of the elongation being known, the corresponding azimuthal angle, 6Z, between the two positions of the star at the times of observation and elongation is given rigorously by the following expression—

| tan δZ = − 2sin21/2P/cotPSsinPZsinP{1+tan2PScosδP+sec2PScotPsinδP} | (13) |

which is expressed as follows for logarithmic computation—

δZ = − m tan Z cos2PS/1 − n + l,

where m = 2 sin2δP/2 cosec 1″, n = 2 sin2PS sin2δP/2, and l=cot P sin δP; l, m, and n are tabulated.

Let A and B (fig. 4) be any two points the normals at which meet at C, cutting the sea-level at p and q; take Dq=Ap, then BD is the difference of height; draw the tangents Aa and Bb at A and B, then aAB is the depression of B at A and bBA that of D A at B; join AD, then BD is determined from the triangle ABD. The triangulation gives the distance between A and B at the sea-level, whence pq = c; thus, A putting Ap, the height of A above sea-level, =H, and pC=r,

Fig. 4.

AD=cI-l-7-Q (14).

Putting D.. and D1, for the actual depressions at A and B, S for the angle at A,

usually called the “ subtended angle, ” and h for BD-5

= i(D1>fD<») (15).

V sm S

and h = ((16)U

The angle at C being = Db+Da, S may be expressed in terms of a single vertical angle and C when observations have been taken at only one of the two points. C, the “contained arc,”=cρ + ν/2ρνcosec 1″ in seconds. Putting D′a, and D'1, for the observed vertical angles, and dn., ¢b for the amounts by which they are affected by refraction, D., =D', ,+¢, , and Db=D′b, +¢;, ; ¢, , and qhi, may differ in amount, but as they cannot be separately ascertained they are always assumed to be equal; the hypothesis is sufficiently exact for practical purposes when both verticals have been measured under similar atmospheric conditions. The refractions being taken equal, the observed verticals are substituted for the true in (15) to find S, and the difference of height is calculated by (16); the third term within the brackets of (14) is usually omitted. The mean value of the refraction is deduced from the formula

4,~l[C-D'.+D' h )} 07)-

An approximate value is thus obtained from the observations between the pairs of reciprocating stations in each district, and the corresponding mean "coefficient of refraction," <#>-*■ C, is computed for the district, and is employed when heights have to be deter- mined from observations at a single station only. When either of the vertical angles is an elevation— £ must be substituted for D in the above expressions.[3]

2. Levelling

Levelling is the art of determining the relative heights of points on the surface of the ground as referred to a hypothetical surface which cuts the direction of gravity everywhere at right angles. When a line of instrumental levels is begun at the sea-level, a series of heights is determined corresponding to what would be found by perpendicular measurements upwards from the surface of water communicating freely with the sea in underground channels; thus the line traced indicates a hypothetical prolonga- tion of the surface of the sea inland, which is everywhere conformable to the earth's curvature.

The trigonometrical determination of the relative heights of points at known distances apart, by the measurements of their mutual vertical angles — is a method of levelling. But the method to which the term " levelling " is always applied is that of the direct determination of the differences of height from the readings of the lines at which graduated staves, held vertically over the points, are cut by the horizontal plane which passes through the eye of the observer. Each method has its own advantages. The former is less accurate,, but best suited for the requirements of a general geographical survey, to obtain the heights of all the more prominent objects on the surface of the ground, whether accessible or not. The latter may be conducted with extreme precision, and is specially valuable for the deter- mination of the relative levels, however minute, of easily accessible points, however numerous, which succeed each other at short intervals apart; thus it is very generally undertaken pari passu with geographical surveys to furnish lines of level for ready reference as a check on the accuracy of the trigonometrical heights. In levelling with staves the measurements are always taken from the horizontal plane which passes through the eye of the observer; but the line of levels which it is the object of the operations to trace is a curved line, everywhere conforming to the normal curvature of the earth's surface, and deviating more and more from the plane of reference as the distance from the station of observation increases. Thus, either a correction for curvature must be applied to every staff reading, or the instru- ment must be set up at equal distances from the staves; the curvature correction, being the same for each staff, will then be eliminated from the difference of the readings, which will thus give the true difference of level of the points on which the staves are set up.

Levelling has to be repeated frequently in executing a long line of levels — say seven times on an average in every mile — and must be conducted with precaution against various errors. Instru- mental errors arise when the visual axis of the telescope is not perpendicular to the axis of rotation, and when the focusing tube does not move truly parallel to the visual axis on a change of' focus. The first error is eliminated, and the second avoided, by placing the instrument at equal distances from the staves; and as this procedure has also the advantage of eliminating the corrections for both curvature and refraction, it should invariably be adopted.

Errors of staff readings should be guarded against by having the staves graduated on both faces, but differently figured, so that the observer may not be biased to repeat an error of the first reading in the second. The staves of the Indian survey have one face painted white with black divisions — feet, tenths and hundredths — from o to 10, the other black with white divisions from 5-55 to 15.55. Deflexion from horizontality may either be measured and allowed for by taking the readings of the ends of the bubble of the spirit-level and applying corresponding corrections to the staff readings, or be eliminated by setting the bubble to the same position on its scale at the reading of the second staff as at that of the first, both being equidistant from the observer.

Certain errors are liable to recur in a constant order and to accumulate to a considerable magnitude, though they may be too minute to attract notice at any single station, as when the work is carried on under a uniformly sinking orrising refraction— from morning to midday or from midday to evening — or when the instru- ment takes some time to settle down on its bearings after being set up for observation. They may be eliminated (i.) by alternating the order of observation of the staves, taking the back staff first at one station and the forward first at the next; (ii.) by working in a circuit, or returning over the same line back, to the origin; (iii.) by dividing a line into sections and reversing the direction of operation in alternate sections. Cumulative error, not eliminable by working in a circuit, may be caused when there is much northing or southing in the direction of the line, for then the sun's light will often fall endwise on the bubble of the level, illuminating the outer edge of the rim at the nearer end and the inner edge at the farther end, and so biasing the observer to take scale readings of edges which are not equidistant from the centre of the bubble; this introduces a tendency to raise the south or depress the north ends of lines of level in the northern hemisphere. On long lines, the employment of a second observer, working independently over the same ground as the first, station by station, is very desirable. The great Fines are usually carried over the main roads of the country, a number of "bench marks" being fixed for future reference. In the ordnance survey of Great Britain lines have been carried across from coast to coast in such a manner that the level of any common crossing point may be found by several independent lines. Of these points there are 166 in England, Scotland and Wales; the dis- crepancies met with at them were adjusted simultaneously by the method of minimum squares.

The sea-level is the natural datum plane for levelling operations, more particularly in countries bordering on the ocean.Sea-level. The earliest surveys of coasts were made for the use of navigators and, as it was considered very important that the charts should everywhere show the minimum depth of water which a vessel would meet with, low water of spring-tides was adopted as the datum. But this does not answer the requirements of a land survey, because the tidal range between extreme high and low water differs greatly at different points on coast-lines. Thus the generally adopted datum plane for land surveys is the mean sea-level, which, if not absolutely uniform all the world over, is much more nearly so than low water. Tidal observations have been taken at nearly fifty points on the coasts of Great Britain, which were connected by levelling operations; the local levels of mean sea were found to differ by larger magnitudes than could fairly be attributed to errors in the lines of level, having a range of 12 to 15 in. above or below the mean of all at points on the open coast, and more in tidal rivers.[4] But the general mean of the coast stations for England and Wales was practically identical with that for Scotland. The observations, however, were seldom of longer duration than a fortnight, which is insufficient for an exact determination of even the short period components of the tides, and ignores the annual and semi- annual components, which occasionally attain considerable magnitudes. The mean sea-levels at Port Said in the Mediterranean and at Suez in the Red Sea have been found to be identical, and a similar identity is said to exist in the levels of the Atlantic and the Pacific oceans on the opposite coasts of the Isthmus of Panama. This is in favour of a uniform level all the world over; but, on the other hand, lines of level carried across the continent of Europe make the mean sea-level of the Mediterranean at Marseilles and Trieste from 2 to 5 ft. below that of the North Sea and the Atlantic at Amsterdam and Brest — a result which it is not easy to explain on mechanical principles. In India various tidal stations on the east and west coasts, at which the mean sea-level has been determined from several years' observations, have been connected by lines of level run along the coasts and across the continent; the differences between the results were in all cases due with greater probability to error generated in levelling over lines of great length than to actual differences of sea-level in different localities.

The sea-level, however, may not coincide everywhere with the geometrical figure which most closely represents the earth's aeoidor surface, but may be raised or lowered, here and there, Deformed under the influence of local and abnormal attrac- Stirface, tions, presenting an equipotential surface — an ellip- soid or spheroid of revolution slightly deformed by bumps and hollows — which H. Bruns calls a " geoid." Archdeacon Pratt has shown that, under the combined influence of the positive attraction of the Himalayan Mountains and the negative attrac- tion of the Indian Ocean, the sea-level may be some 560 ft. higher at Karachi than at Cape Comorin; but, on the other hand, the Indian pendulum operations have shown that there is a deficiency of density under the Himalayas and an increase under the bed of the ocean, which may wholly compensate for the excess of the mountain masses and deficiency of the ocean, and leave the surface undisturbed. If any bumps and hollows exist, they cannot be measured, instrumentally; for the instrumental levels will be affected by the local attractions precisely as the sea-level is, and will thus invariably show level surfaces even should there be considerable deviations from the geometrical figure.

3. Topographical Surveys

The skeleton framework of a survey over a large area should be triangulation, although it is frequently combined with travers- ing. The method of filling in the details is necessarily influenced to some extent by the nature of the framework, but it depends mainly on the magnitude of the scale and the requisite degree of minutiae. In all instances the principal triangles and circuit traverses have to be broken down into smaller ones to furnish a sufficient number of fixed points and lines for the subsequent operations. The filling in may be performed wholly by linear measurements or wholly by direction intersections, but is most frequently effected by both linear and angular measures, the former taken with chains and tapes and offset poles, the latter with small theodolites, sextants, optical squares or other reflect- ing instruments, magnetized needles, prismatic compasses and plane tables. When the scale of a survey is large, the linear and angular measures are usually recorded on the spot in a field- book and afterwards plotted in office; when small they are sometimes drawn on the spot on a plane table and the field-book is dispensed with.

In every country the scale is generally expressed by the ratio of some fraction or multiple of the smallest to the largest national units of length, but sometimes by the fraction which indicates the ratio of the length of a line on the paper to that of the correspond- ing line on the ground. The latter form is obviously preferable, being international and independent of the various units of length adopted by different nations (see Map). In the ordnance survey of Great Britain and Ireland and the Indian survey the double unit of the foot and the Gunter's link (=-ft?irof a foot) are employed, the former invariably in the triangulation, the latter generally in the traversing and filling in, because of its convenience in calculations and measurements of area, a square chain of 100 Gunter's links being exactly one-tenth of an acre.

In the ordnance survey all linear measures are made with the Gunter's chain, all angular with small theodolites only; neither magnetized nor reflecting instruments nor plane tables are ever employed, except in hill sketching. As a rule the filling in is done by triangle-chaining only; traverses with theodolite and chain are occasionally resorted to, but only when it is necessary to work round woods and hill tracts across which right lines cannot be carried.

Detail surveying by triangles is based on the points of the minor triangulation. The sides are first chained perfectly straight, all the points where the lines of interior detail cross the sides being fixed; the alignment is effected with a small theodolite, and marks are established at the crossing points and at any other points on the sides where they may be of use in the subsequent operations. The surveyor is given a diagram of the triangulation, but no side lengths, as the accuracy of his chaining is tested by comparison with the trigonometrical values. Then straight lines are carried across the intermediate detail between the points established on the sides; they constitute the principal " cutting up or split lines"; their crossings of detail are marked in turn and straight lines are run between them. The process is continued until a sufficient number of lines and marks have been established on the ground to enable all houses, roads, fences, streams, railways, canals, rivers, boundaries and other details to be conveniently measured up to and fixed. Perpendicular offsets are limited to eighty and twenty links for the respective scales of 6 in. to a mile and S1 ta>.

When a considerable area has to be treated by traverses it is divided into a number of blocks of convenient size, bounded by roads, rivers or parish boundaries, and a " traverse on the meridian of the origin " is carried round the periphery of each block. Be- ginning at a trigonometrical station, the theodolite is set to circle reading o° o' with the telescope pointing to the north, and at every " forward " station of the traverse the circle is set to the same reading when the telescope is pointed at the " back " station as was obtained at the back station when the telescope was pointing to the forward one. When the circuit is completed and the theodo- lite again put up at the origin and set on the last back station with the appropriate circle reading, the circle reading, with the telescope again pointed to the first forward station, will be the same as at first, if no error has' been committed. This system establishes a convenient check on the accuracy of the operations and enables the angles to be readily protracted on a system of lines parallel to the meridian of the origin. As a further check the traverse is connected with all contiguous trigonometrical stationsby measured angles and distances. Traverses are frequently carried between the points already fixed on the sides of the minor triangles; the initial side is then adopted, instead of the meridian, as the axis of co-ordinates for the plotting, the telescope being pointed with circle reading o° o' to either of the trigonometrical stations at the ex- tremities of the side.

The plotting is done from the field-books of the surveyors by a separate agency. Its accuracy is tested by examination on the ground, when all necessary addenda are made. The examiner — who should be surveyor, plotter and draughtsman — verifies the accuracy of the detail by intersections and productions and occasional direct measurements, and generally endeavours to cause the details under examination to prove the accuracy of each other rather than to obtain direct proof by remeasurement. He fixes con- spicuous trees and delineates the woods, footpaths, rocks, precipices, steep slopes, embankments, &c, and supplies the requisite infor- mation regarding minor objects to enable a draughtsman to make a perfect representation according to the scale of the map. In ex- amining a coast-line he delineates the foreshore and sketches the strike and dip of the stratified rocks. In tidal rivers he ascertains and marks the highest points to which the ordinary tides flow. The examiner on the 25-344 ui. scale ( = 2sW) is required to give all necessary information regarding the parcels of ground of different character — whether arable, pasture, wood, moor, moss, sandy — defining the limits of each on a separate tracing if necessary. He has also to distinguish between turnpike, parish and occupation roads, to collect all names, and to furnish notes of military, baronial and ecclesiastical antiquities to enable them to be appropriately represented in the final maps. The latter are subjected to a double examination — first in the office, secondly on the ground; they are then handed over to the officer in charge of the levelling to have the levels and contour lines inserted, and finally to the hill sketchers, whose duty it is to make an artistic representation of the features of the ground.

In the Indian survey all filling in is done by plane-tabling on a basis of points previously fixed ; the methods differ simply in the extent to which linear measures are introduced to supplement the direction rays of the plane-table. When the scale of the survey is small, direct measurements of distance are rarely made and the filling is usually done wholly by direction intersections, which fix all the principal points, and by eye-sketching; but as the scale is increased linear measures with chains and offset poles are introduced to the extent that may be desirable. A sheet of drawing paper is mounted on cloth over the face of the plane-table; the points, previously fixed by triangulation or otherwise, are projected on it — the collateral meridians and parallels, or the rectangular co-ordinates, when these are more convenient for employment than the spherical, having first been drawn; the plane-table is then ready for use. Operations are begun at a fixed point by aligning with the sight rule on another fixed point, which brings the meridian line of the table on that of the station. The magnetic needle may now be placed on the table and a position assigned to it for future reference. Rays are drawn from the station point on the table to all conspicuous objects around with the aid of the sight rule. The table is then taken to other fixed points, and the process of ray-drawing is repeated at each; thus a number of objects, some of which may become available as stations of observation, are fixed. Additional stations may be established by setting up the table on a ray, adjusting it on the back station — that from which the ray was drawn — and then obtaining a cross intersection with the sight rule laid on some other fixed point, also by interpolating between three fixed points situated around the observer. The magnetic needle may not be relied on for correct orientation, but is of service in enabling the table to be set so nearly true at the outset that it has to be very slightly altered afterwards. The error in the setting is indicated by the rays from the surrounding fixed points intersecting in a small triangle instead of a point, and a slight change in azimuth suffices to reduce the triangle to a point, which will indicate the position of the station exactly. Azimuthal error being less apparent on short than on long lines, interpolation is best performed by rays drawn from near points, and checked by rays drawn to distant points, as the latter show most strongly the magnitude of any error of the primary magnetic setting. In this way, and by self-verificatory traverses " on the back ray " between fixed points, plane-table stations are established over the ground at appropriate intervals, depending on the scale of the survey; and from these stations all surrounding objects which the scale permits of being shown are laid down on the table, sometimes by rays only, sometimes by a single ray and a measured distance. The general configuration of the ground is delineated simultaneously. In checking and examination various methods are followed. For large scale work in plains it is customary to run arbitrary lines across it and make an independent survey of the belt of ground to a dis- tance of a few chains on either side for comparison with the original survey; the smaller scale hill topography is checked by examination from commanding points, and also by traverses run across the finished work on the table.

4. Geographical Surveying

The introduction by mechanical means of superior graduation in instruments of the smaller class has enabled surveyors to effect Base good results more rapidly, and with less expenditure

Measure- on equipment and on the staff necessary for transport meats. j n the fieidj than was formerly possible. The 12-in. theodolite of the present day, with micrometer adjustments to assist in the reading of minute subdivisions of angular graduation, is found to be equal to the old 24-in. or even 36-in. instruments. New Methods for the measurement of bases have largely superseded the laborious process of measurement by the align- ment of " compensation " bars, though not entirely independent of them. The Jaderin apparatus, which consists of a wire 25 metres in length stretched along a series of cradles or supports, is the simplest means of measuring a base yet devised; and experi- ments with it at the Pulkova observatory show it to be capable of producing most accurate results. But there is a measurable defect in the apparatus, owing to the liability of the wires to change in length under variable conditions of temperature. It is therefore considered necessary, where base measurements for geodetic purposes are to be made with scientific exactness, that the Jaderin wires should be compared before and after use with a standard measurement, and this standard is best attained by the use of the Brunner, or Colby, bars. The direct process of measurement is not extended to such lengths as formerly, but from the ends of a shorter line, the length of which has been exactly determined, the base is extended by a process of triangulation.

There are vast areas in which, while it is impossible to apply the elaborate processes of first-class or " geodetic " triangulation, Secondary it is nevertheless desirable that we should rapidly Triangula- acquire such geographical knowledge as will enable tlon. us t0 j a y d own political boundaries, to project roads

and railways, and to attain such exact knowledge of special localities as will further military ends. Such surveys are called by various names — military surveys, first surveys, geographical surveys, &c; but, inasmuch as they are all undertaken with the same end in view, i.e. the acquisition of a sound topographical map on various scales, and as that end serves civil purposes as much as military, it seems appropriate to designate them geo- graphical surveys only.

The governing principles of geographical surveys are rapidity and economy. Accuracy is, of course, a recognized necessity, but Principles t ^ ie term must admit of a certain elasticity in geo- which graphical work which is inadmissible in geodetic

govern Geo- or cadastral functions. It is obviously foolish to graphical ex p en d as much money over the elaboration of topo- graphy in the unpeopled sand wastes which border the Nile valley, for instance (albeit those deserts may be full of topographical detail), as in the valley itself — the great centre of Egyptian cultivation, the great military highway of northern Africa. On the other hand, the most careful accuracy attainable in the art of topographical delineation is requisite in illustrating the nature of a district which immediately surrounds what may prove hereafter to be an important military position. And this, again, implies a class of technical accuracy which is quite apart from the rigid attention to detail of a cadastral survey, and demands a much higher intelligence to compass.

The technical principles of procedure, however, are the same in geographical as in other surveys. A geographical survey must equally start from a base and be supported by triangulation, or at least by some process analogous $**„%** of to triangulation, which will furnish the necessary skeleton on which to adjust the topography so as to ensure a complete and homogeneous map.

This base may be found in a variety of ways. If geodetic

triangulation exists in the country, that triangulation should of

course include a wide extent of secondary determina- _. _.

„ . , 1 , . .,1, Ineij&se*

tions, the fixing of peaks and points in the landscape far away to either flank, which will either give the data for further extension of geographical triangulation, or which may even serve the purposes of the map-maker without any such extension at all. In this manner the Indus valley series of the triangulation of India has furnished the basis for surveys across Afghanistan and Baluchistan to the Oxus and Persia.

Should no such preliminary determinations of the value of one or two starting-points be available, and it becomes necessary to measure a base and to work db initio, the Jaderin wire apparatus may be adopted. It is cheap (cost about £50), and far more accurate than the process of measuring either by any known " subtense " system (in which the distance is computed from the angle subtended by a bar of given length) or by measurement with a steel chain. This latter method may, however, be adopted so long as the base can be levelled, repeated measurements obtained, and the chain compared with a standard steel tape before and after use.

The initial data on which to start a comprehensive scheme of triangulation for a geographical survey are: (1) latitude; i a it] al n a ta (2) longitude; (3) azimuth; and (4) altitude, and this data should, if possible, be obtained pari passu with the measurement of the base.