20 Hrs. 40 Min./Chapter 13

CHAPTER XIII

RETROSPECT

PREPARATIONS . . . the flight . . . England . . . our return . . . the first receptions . . . photographs, interviews . . . New York, Boston, Chicago . . . the many invitations not accepted because of lack of time . . . mayors, celebrities, governors . . . splendid flyers; Wilkins, Byrd, Chamberlin, Thea Rasche, Balchen, Ruth Nichols, Reed Landis . . . speeches, lunches, radio microphones . . . acres of clippings (unread) . . . editors, promoters . . . settlement houses, aldermen's offices . . . gracious hostesses, camera-wise politicians . . . private cars, palatial planes . . . and then my book . . . hours of writing piled up in the contented isolation (stoically maintained) of a hospitable Rye home. . . friends, a few parties . . . swimming, riding, dancing, in tantalizing driblets. . . brief recesses from work . . . Tunney vs. Heeney, my first fight (a boxer's career is measured by minutes in the ring; an

aviator's by hours in the air) . . . more writing―much more.

Such is my jumbled retrospect of the seven weeks which have crowded by since we returned to America.

Finally the little book is done, such as it is. Tomorrow I am free to fly.

Now, I have checked over, from first to last, this manuscript of mine. Frankly, I'm far from confident of its air-worthiness, and don't know how to rate its literary horse-power or estimate its cruising radius and climbing ability. Confidentially, it may never even make the take-off.

If a crash comes, at least there'll be no fatalities. No one can see more comedy in the disaster than the author herself. Especially because even the writing of the book, like so much else of the flight and its aftermaths, has had its humor—some of it publishable!

I never knew that a "public character" (that, Heaven help me, apparently is my fate since the flight) could be the target of so much mail.

"Please send me $150; it will just pay for my divorce which I must have. . . ." So read one letter, plus details anent the necessity of the proposed separation. Autographing, I discover, is a national mania. Requests for photographs, freak suggestions, involved communications from inventors, pathetic appeals, have been numerous.

Yes, the mail has brought diverse proposals of marriage, and approximations thereof. Perhaps the widespread publication of my photograph has kept the quantity down!

Best of all the letters are those from average people about the country—mostly women—who have found some measure of satisfaction, or perhaps a vicarious thrill, in the experiment of which I happened to be a small part. For their congratulations and friendly messages I find myself always deeply grateful.

A wave of invitations almost engulfed me, and offers of employment, many of them bewilderingly generous, proved part of the harvest of notoriety. The psychology of inferring that flying the Atlantic equips one for an advertising managership or banking, leaves me puzzled.

However, the correspondence of a "goldfish" isn't all bouquets, by any means.

Cigarettes have nearly been my downfall. Not subjectively, understand, for my indulgence is decently limited; the count, I think, shows the restrained total of three for the current year. It's not what I did, but what I said, that caused trouble. I wickedly "endorsed" a certain cigarette which was carried by the boys on the Friendship. This I did to benefit three gallant gentlemen,—Commander Byrd, to whose South Polar Expe--

REAR PLATFORM STUFF

WITH A MODEL OF THE FRIENDSHIP PRESENTED BY A BOSTON SCHOOLBOY

It happens that I don't—it just never seemed worth while. Anyway, the incident struck some journalistic sparks. Amusing among them is this from the "New Yorker":

One of the greatest personal sacrifices of all times, as we look at it, was the sacrifice Miss Earhart made in endorsing a brand of cigarettes so she could earn fifteen hundred dollars to contribute to Commander Byrd's South Pole flight.  She admitted in her letter that she "made the endorsement deliberately." Commander Byrd, replying, said that it seemed to him "an act of astonishing generosity." Pioneering must go on, whatever the toll; the waste places must be conquered. Since, however, the faculty of Reed University, in Oregon, declares that it is impossible for a person blindfolded to tell one cigarette from another, it seems to us that the only honorable course left for Commander Byrd, in order to vindicate science and validate Miss Earhart's gift, is to fly to the South Pole blindfolded.

She admitted in her letter that she "made the endorsement deliberately." Commander Byrd, replying, said that it seemed to him "an act of astonishing generosity." Pioneering must go on, whatever the toll; the waste places must be conquered. Since, however, the faculty of Reed University, in Oregon, declares that it is impossible for a person blindfolded to tell one cigarette from another, it seems to us that the only honorable course left for Commander Byrd, in order to vindicate science and validate Miss Earhart's gift, is to fly to the South Pole blindfolded.

Photographers, too, are innocent (sometimes) instruments of a critical fate. (I've never fathomed why photographers always want "a-great-big-smile-please"; and prefer their victims waving.) I did contrive to resist the blandishments of one who would have had me pictured blowing a kiss to Pittsburgh. But in Chicago, when the boys and girls of the Hyde Park High School turned out to see their Atlantic-flying Alumna, the picture men asked me to step forward from the stage upon a grand piano backed up to its edge, so as to include the youngsters as well as myself. Picture taken, picture published. Promptly arrived an acid letter from a friend: "How did you get on the piano?"

Doubtless she visualized me in scandalizing progress through the west, leaping from piano to piano.

The school incident reminds me of my peripatetic education. My father was a railroad claim agent and attorney, his work seldom keeping him long in one place. As a result I graced the high schools of six different communities, and happened to be in Chicago when graduation day rolled around. During the first turmoil after our London arrival, cablegrams came from at least four communities, each one doing me the honor of claiming me as its very own. Beyond proclaiming the fact that I spent more time in Atchison, Kansas, than anywhere else, discretion, it seems to me, dictates silence as to other comparative allegiances.

A considerable crop of poetry, verse, and rhyme is chargeable to our flight, some of it far more meritorious than the subject sung. From the direct-by-mail offering, with which friendly souls seem wont to deluge those whose names appear in print, I garner the following excerpts:

Two experiences which were privileges, too, of the busy weeks, stand out oddly in my memory.

Shamelessly I confess my admiration for motorcycle policemen. Though they have spoken harshly to me on occasion they are so good to look at, I've quite forgiven―most of them. Gallant figures cycle cops, weaving through traffic, provoking drivers to follow suit—and get a ticket.

In the autocratic days of our post-flight glory we were whirled about with motorcycle escort, unmindful of traffic lights and speed ordinances. Of an afternoon I motored to New York's new Medical Center, with one of the escorts driving a side-car. On the way back to the Biltmore I transferred from the limousine to that side-car. . . There wasn't a speedometer so I don't know exactly, but I suspect that fifty m.p.h. doesn't tell the story.

That was one of the cherished experiences. The second found me in a locomotive cab of the Pennsylvania Railroad, bedecked in overalls, goggles and cap. The ride from Pittsburgh to Altoona, round the Horseshoe Bend, was not so fast as flying, about as noisy, and much dirtier. Also far more hot. If and when my feminine readers take up locomotive travel, let them wear heavily soled shoes. Mine were fairly thin—and the fire box heated the floor below where I sat when I couldn't stand and stood when I couldn't sit. Even the photographs, incidental to these experiences, did not detract from my enjoyment. However, some of them clipped subsequently from newspapers, arrived thoughtfully labelled bologna.

There were many editorials in both England and America. Some appraised the technical accomplishments of the flight generously. But more interesting than the bouquets were the brickbats, especially when shied directly at me— as they often were.

As to the part I personally played in the flight I have tried to be entirely frank always. The credit belongs to the boys, to the ship and to its backer. I was a passenger. The fact that I happen to be a small-ship pilot, reasonably experienced in the air, didn't affect the situation other than having contributed to my selection.

Said the "New York World":

Using Newfoundland and Ireland, and possibly the Azores, as fuel stops, commercial airplaning between the Old World and the New appears likely to become feasible within the not very distant future. To have shared with her skilled companions in bringing that development a step nearer is higher honor for Miss Earhart than the sporting record of the first air crossing accomplished by a woman.

Not only "honor," but satisfaction—the joy of a share, however small, in a great adventure.

When we were in London a clipping from "The Church Times" came to me. The envelope was addressed in the shaky handwriting of an elderly person. There was no letter and no signature, but certain sentences in the article were underlined.

Here is that clipping as it greeted me, the underlined sentences printed in italics:

Read Mark Learn

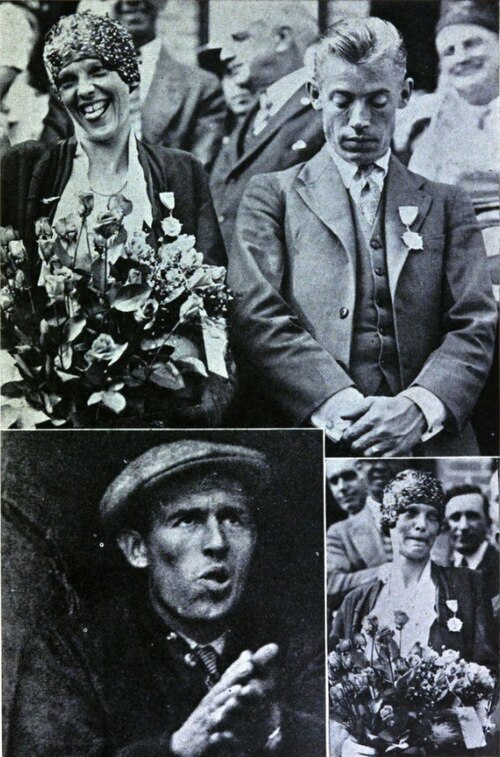

THE CAMERA, TOO, HANDED US BRICKBATS—THESE ARE CULLED FROM OUR LESS (OH, FAR!) FLATTERING PHOTOGRAPHIC SOUVENIRS

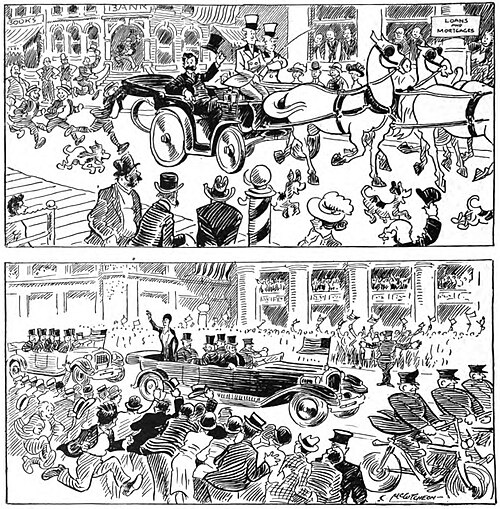

YESTERDAY'S HERO, AND TODAY'S

John T. McCutcheon in The Chicago Tribune

For compensation, here is another clipping, a chuckling commentary upon back-seat driving, of course utterly unfair to my sex:

As a Back Seat Driver Would Have Made That Flight

(Two Hundred Miles Off Trepassey.)

The Woman: Where are we now?

Pilot: I can't quite make out.

The Woman:There must be some way of telling.

Pilot: I just don't seem to recognize anything.

The Woman: Are you sure that place we left was Trepassey?

Pilot: That's what it was called on the map.

The Woman: Well, maybe the map was wrong. I don't feel as if we were headed for Europe. Hadn't we better stop and make certain?

***

(One Thousand Miles Out.)

The Woman: Are we on the right route now?

Navigator: I'm pretty certain, but I wouldn't swear to it.

The Woman: I'll bet we're miles off going ahead blindly if we're not certain!

Pilot: We may be a little off the course.

The Woman: I'll bet we're miles off it. I could have told you 600 miles

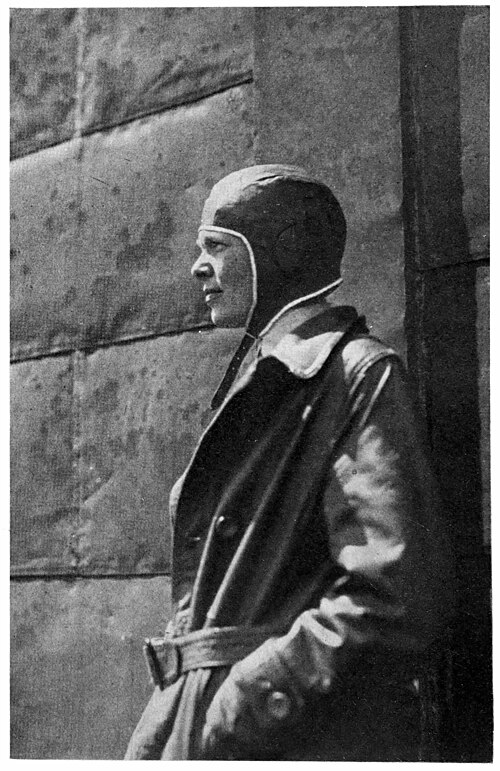

FROM PITTSBURGH TO ALTOONA

BEFORE THE FLIGHT IN BOSTON—A. E. AND G. P. P.

back we weren't going the right way. Can't you straighten things out by looking at the map?

Navigator: The map won't do us any good just now.

The Woman: What's a map for, then? I'll bet if I had a map I could tell where I was.

***

(Twelve Hundred Miles Out.)

The Woman: Why do we have to keep flying in this awful fog? It's perfectly terrible!

Pilot: There's no way of avoiding it.

The Woman: That's a perfectly silly thing to say. When you sail right into a fog and stay in it for hours I should think you'd admit you'd made a mistake and not drive calmly on, pretending it was necessary.

Pilot: We've flown way up in the air to get out of it and we've flown close to the ocean to escape it, but it's no use.

The Woman: I'll bet if you'd turn a sharp right you'd get out of it in no time. I told you to take a sharp right five hours ago.

Pilot: We can't take any sharp right turns and reach Europe, my dear.

The Woman: How do you know without trying?

***

(Fifteen Hundred Miles Out.)

The Woman: Well, I just know we're lost and it's all your fault.

Navigator: Please have a heart. Everything'll come out okay if you have patience.

The Woman: I've had patience for hours, and for all I know may be right back where I started. If you don't know exactly where you are why don't you STOP AND ASK SOMEBODY?

***

(Over South Wales.)

The Woman: Look! It's land! What place is it?

Pilot: The British Isles.

The Woman: Isn't it just splendid? Here we are across the Atlantic in no time just as we had planned. And you boys were so NERVOUS AND UNCERTAIN ABOUT IT ALL THE WAY OVER!

H. I. Phillips added that to the gaiety of aviation, in the Sun Dial of the "New York Sun." By the way, at the N. A. A. luncheon at the Boston reception I was introduced as the most famous b. s. d. in the world.

One of the largest organizations connected with the Friendship flight was the I-knew-all-about-it-beforehand-club. Most of them contrived to get into the papers pretty promptly. Some charter members recorded that they turned down tempting offers to pilot the ship, actuated by an exuberant loyalty to Uncle Sam.

Here, in conclusion of this hodge-podge are three more extacts from the press, random examples of what men do and say.

The first is from the "English Review," evidence that the world is far from any universal air-mindedness:

The Latest Atlantic Flight

The Atlantic has been flown again, and no one will grudge Miss Earhart her triumph. The achievement has, however, produced the usual crop of inspired paragraphs on the future of aviation, and the usual failure to face the fact that air transport is the most unreliable and the most expensive form of transport available. No amount of Atlantic flights will alter these facts, because they happen, as things are, to be inherent in the nature of men and things. Absurd parallels are drawn between people who talk sense about the air today, and people who preferred stage-coaches to railways. The only parallel would be, of course, between such people and any who insist today in flying to Paris by balloon instead of by aeroplane. Everyone wants to see better, safer and cheaper aeroplanes. If the Air League can offer us a service which will take us to Paris in half-an-hour for half-a-crown, I would even guarantee that Neon would be the first season-ticket holder. But all this has nothing to do with the essential fact that not a single aeroplane would be flying commercially today without the Government subsidy, for the simple reason that by comparison with other forms of transport air transport is uneconomic. To talk vaguely of the great developments which will occur in the future is no answer, unless you can show that the defects of air transport are technical defects which can be overcome by mechanical means. A few of them, of course, are, but the overwhelming defects are due to the nature of the air itself. It is very unfortunate, but we fail to see how it can be helped.

After all, the "Review" may be right; but somehow its viewpoint is reminiscent of certain comment when the Wrights were experimenting at Kitty Hawk. Also of the mathematical deductions which proved beyond doubt that flight in a heavier than air machine was impossible.

To balance the pessimism here is an editorial from this morning's "New York Times"—current commentary upon characteristic news of the day:

Steamship and Plane

In the world of commerce a gain of fifteen hours in the receipt of letters from Europe may have important consequences. The experiment of the French Line was to be only a beginning in speeding Atlantic mails. It is yet planned to launch planes when steamships are 800 miles from the port of destination. With a following wind the amphibian plane piloted by Commander Demougeot flew at the rate of 130 miles an hour and made the distance of over 400 miles to Quarantine in three hours and seventeen minutes. In such weather as prevailed it could have been catapulted from the Ile de France with no more hazard when

TWO CHARACTERISTIC PAGES FROM THE TRANS-ATLANTIC LOG BOOK. THE DIFFICULTY OF WRITING IN THE DARK IS EXEMPLIFIED BY THE PENMANSHIP OF THE SECOND PAGE

BOSTON, 1928

Ten years ago the experiment of hurrying mail to shore in a plane from a surface ship 400 miles out at sea would not have been attempted. So great has been the improvement in airplane design that what the Ile de France has done will soon become the regular order. It is not wildly speculative to think of dispatching a plane after a liner on a well-traveled route in these days of excellent radio communication. It would be well to use for that purpose amphibian or seaplanes carrying fuel enough to take them all the way across the Atlantic if necessary.

It is conceivable that ocean flight between Europe and the United States will be the sequel to a ship-and-plane system of mail delivery, the distances covered by the plane becoming longer and longer until the steamship can be dispensed with altogether.

And last, just an item of news, gleaned from "Time":

Broker's Amphibian

Between his summer home on Buzzard's Bay, Mass., and his brokerage offices in Manhattan, Richard F. Hoyt commutes at 100 miles an hour. He uses a Loening amphibian biplane, sits lazily in a cabin finished in dark brown broadcloth and saddle leather, with built-in lockers containing pigskin picnic cases. Pilot Robert E. Ellis occupies a forward cockpit, exposed to the breezes. But occasionally Broker Hoyt wishes to pilot himself. When this happens he pulls a folding seat out of the cabin ceiling, reveals a sliding hatch. Broker Hoyt mounts to the seat, opens the hatch, inserts a removable joystick in a socket between his feet. Rudder pedals are already installed in front of the folding seat. Ile has thus created a rear cockpit, with a full set of controls. Broker Hoyt becomes Pilot Hoyt.

With such excerpts, from the newspapers and the magazines of every day, one could go on endlessly, for aviation is woven ever closer into the warp of the world's news. Ours is the commencement of a flying age, and I am happy to have popped into existence at a period so interesting.