A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Additional Accompaniments

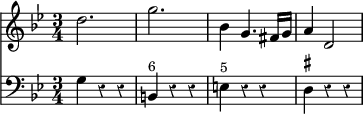

ADDITIONAL ACCOMPANIMENTS. In the published scores of the older masters, especially Bach and Handel, much is to be met with which if performed exactly as printed will fail altogether to realise the intentions of the composer. This arises partly from the difference in the composition of our modern orchestras as compared with those employed a century and a half ago; partly also from the fact that it was formerly the custom to write out in many cases little more than a skeleton of the music, leaving the details to be filled in at performance from the 'figured bass.' The parts for the organ or harpsichord were never written out in full except when these instruments had an important solo part; and even then it was frequently the custom only to write the upper part and the bass, leaving the harmonies to be supplied from the figures by the player. Thus, for instance, the first solo for the organ in Handel's Organ Concerto in G minor No. 1, is thus written in the score:—

It is evident from the figures here given that the passage is intended to be played in the following, or some similar way,

and that a performer who confined himself to the printed notes would not give the effect which Handel designed. Similar instances may be found in nearly all the works of Bach and Handel, in many of which nothing whatever but a figured bass is given as a clue to the form of accompaniment. At the time at which these works were written the art of playing from a figured bass was so generally studied that any good musician would be able to reproduce, at least approximately, the intentions of the composer from such indications as the score supplied. But when, owing to the growth of the modern orchestra, the increased importance given to the instrumental portion of the music, and the resultant custom which has prevailed from the time of Haydn down to our own day of writing out in full all parts which were obbligato—i. e. necessary to the completeness of the music—the art of playing from a figured bass ceased to be commonly practised, it was no longer possible for whoever presided at the organ or piano at a performance to complete the score in a satisfactory manner. Hence arose the necessity for additional accompaniments, in which the parts which the composer has merely indicated are given in full, instead of their being left to the discretion (or indiscretion, as the case might be) of the performer.

2. There are two methods of writing additional accompaniments. The first is to write merely a part for the organ, as Mendelssohn has done with so much taste and reserve in his edition of 'Israel in Egypt,' published for the London Handel Society. There is more than one reason, however, for doubting whether even his accompaniment would succeed in bringing out the true intentions of the composer. In the first place, our modern orchestras and choruses are so much larger than those mostly to be heard in the time of Bach and Handel, that the effect of the combination with the organ must necessarily be different. An organ part filling up the harmony played by some twenty or twenty-four violins in unison (as in many of Handel's songs) and supported by perhaps twelve to sixteen bass instruments will sound very different if there is only half that number of strings. Besides, our modern organs often differ hardly less from those of the last century than our modern orchestras. But there is another and more weighty reason for doubting the advisability of supplementing the score by such an organ part. In the collection of Handel's conducting-scores, purchased some twenty years since by M. Schoelcher, is a copy of 'Saul' which contains full directions in Handel's own writing for the employment of the organ, reprinted in the edition of the German Handel Society;[1] from which it clearly appears that it was nowhere used to fill up the harmony in the accompaniment of the songs. This must therefore have been given to the harpsichord, an instrument no longer in use, and which, if it were, would not combine well with our modern orchestra. It is therefore evident that such an organ part as Mendelssohn has written for the songs in 'Israel,' appropriate as it is in itself, is not what the composer intended.

3. The method more frequently and also more successfully adopted is to fill up the harmonies with other instruments—in fact to rewrite the score. Among the earliest examples of this mode of treatment are Mozart's additional accompaniments to Handel's 'Messiah,' 'Alexander's Feast,' 'Acis and Galatea,' and 'Ode for St. Cecilia's Day.' These works were arranged for Baron van Swieten, for the purpose of performances where no organ was available. What was the nature of Mozart's additions will be seen presently; meanwhile it may be remarked in passing, that they have always been considered models of the way in which such a task should be performed. Many other musicians have followed Mozart's example with more or less success, among the chief being Ignaz Franz Mosel, who published editions of 'Samson,' 'Jephtha,' 'Belshazzar,' etc., in which not only additional instrumentation was introduced, but utterly unjustifiable alterations were made in the works themselves, a movement from one oratorio being sometimes transferred to another; Mendelssohn, who (in early life) rescored the 'Dettingen Te Deum,' and 'Acis and Galatea'; Dr. Ferdinand Hiller, Professor G. A. Macfarren, Sir Michael Costa, Mr. Arthur Sullivan, and last (and probably best of all) Robert Franz. This eminent musician has devoted special attention to this branch of his art; and for a complete exposition of the system on which he works we refer our readers to his 'Offener Brief an Eduard Hanslick,' etc. (Leipzig, Leuckart, 1871). Franz has published additional accompaniments to Bach's 'Passion according to St. Matthew,' 'Magnificat,' and several 'Kirchen-cantaten,' and to Handel's 'L'Allegro' and 'Jubilate.'

4. The first, and perhaps the most important case in which additions are needed to the older scores is that which so frequently occurs when no instrumental accompaniment is given excepting a figured bass. This is in Handel's songs continually to be met with, especially in cadences, and a few examples follow of the various way in which the harmonies can be filled up.

At the end of the air 'Rejoice greatly' in the 'Messiah,' Handel writes thus,—

![{\key bes \major \time 4/4 \partial 4 \mark \markup \small "1."

<< \clef treble { ees''4^\markup { \small \italic "Voce" } | f' ees''16([ d'')] c''([ bes')] a'4.\fermata bes'8 | bes'4 }

\addlyrics { thy King com -- eth un -- to thee }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key bes \major

{ c4^\markup { \small \italic "Bassi" } | a, r8 bes, f4\fermata f, | bes } }

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/d/sdeepa8xheivbxsxzpuo834bf3sbp15/sdeepa8x.png)

Mozart gives the harmonies in this passage to the stringed quartett, as follows:—

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\key bes \major \time 4/4 \partial 4 \mark \markup \small "2."

<< \clef treble

<< { r4^\markup { \small \italic "Viol. 1 & 2" } | r8 ees' d' bes' a'4.\fermata bes'8 | bes'4 }

\\

{ s4 | s8 c' bes d' c' d'16 ees' f'8 ees'8 | d'4 }

>>

\new Staff { \clef alto \key bes \major { r4^\markup { \small \italic "Viola" } | r8 a( bes f) f2\fermata | f } }

\new Staff { \new Voice = "voce" \clef treble \key bes \major

{ ees''4^\markup { \small \italic "Voce" } | f' ees''16([ d'')] c''([ bes')] a'4.\fermata bes'8 | bes'4 } }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "voce" { thy King com -- eth un -- to thee }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key bes \major { c4^\markup { \small \italic "Bassi" } | a, r8 bes, f4\fermata f, | bes } }

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/w/owij4wc2uzz8uzsrvtwylackt73nr97/owij4wc2.png)

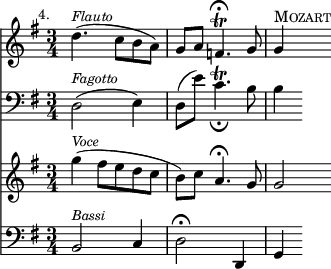

Sometimes in similar passages the accompaniments are given to a few wind instruments with charming effect, as in the following examples by Mozart. For the sake of comparison we shall in each instance give the score in its original state before quoting it with the additional parts. Our first example is from the close of the song 'What passion,' in the 'Ode for St. Cecilia's Day.'

In the first of the foregoing quotations (No. 4) it will be seen that Mozart has simply added in the flute and bassoon the harmony which Handel no doubt played on the harpsichord. In the next (No. 6), from 'He was despised,' the harmony is a little fuller.

In all the above examples the treatment of the harmony is as simple as possible. When similar passages occur in Bach's works, however, they require a more polyphonic method of treatment, as is proved by Franz in his pamphlet above referred to. A short extract from the 'Passion according to Matthew' will show in what way his music can be advantageously treated.

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 3/8 << { \new Voice = "voce" \clef treble \key a \major { fis'8([^\markup { \small \italic Voce } dis'')] bis' | fis'([ gis'16 fis')] e'( dis') | e'8([ cis'')] b' | a'16([ gis' fis' eis')] fis'8 } }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "voce" { dir ge -- bäh -- ren treu -- er Je -- su }

\new Staff { \clef bass \key a \major { a16(^\markup { \small \italic Bassi } gis fis e dis cis) | bis,8( gis, bis,) | cis16( b, a, gis, fis, eis,) | fis,8 gis, a, } }

\figures { < 6 >8 < 6 >8 < 6 >8 < _ >4. < _ >4 <5 4 2>8 < _ >4 < 6 >8 }

>> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/q/oqj51ioimi1gt7lpq2brgw7hr8js293/oqj51ioi.png)

The figures here give the clue to the harmony, but if simple chords were used to fill it up, as in the preceding extracts, they would, in Franz's words, 'fall as heavy as lead among Bach's parts, and find no support among the constantly moving basses.' Franz therefore adopts the polyphonic method, and completes the score as follows:—

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\key a \major \time 3/8

<< \clef treble

{ fis'8^\markup { \small \italic Viol. 1 } dis''16( cis'' bis' cis'') |

dis''8( bis') gis'16( fis') |

e'8( cis'' b') | a'16( gis' fis' eis') fis'8 | }

\new Staff

{ \clef treble \key a \major

{ cis'8(^\markup { \small \italic Viol. 2 } a' fis) |

dis'8( e'16 fis' e' d') |

cis'4 cis'8 | cis'4 a8 } }

\new Staff

{ \clef alto \key a \major

{ fis'8^\markup { \small \italic Viola } r fis16( a) |

gis4. ~ | gis | a8( b cis) } }

\new Staff

{ \new Voice = "voce" \clef treble \key a \major

{ fis'8([^\markup { \small \italic Voce } dis'')] bis' |

fis'([ gis'16 fis')] e'( dis') | e'8([ cis'')] b' |

a'16([ gis' fis' eis')] fis'8 } }

\new Lyrics \lyricsto "voce" { dir ge -- bäh -- ren treu -- er Je -- su }

\new Staff

{ \clef bass \key a \major

{ a16(^\markup { \small \italic Bassi } gis fis e dis cis) |

bis,8( gis, bis,) |

cis16( b, a, gis, fis, eis,) | fis,8 gis, a, } }

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/1/q1o7u3yvik9e54we39pi1pvjibm6umd/q1o7u3yv.png)

Somewhat resembling the examples given above is the case so often to be found both in Bach and Handel in which only the melody and the bass are given in the score. There is hardly one of Handel's oratorios which does not contain several songs accompanied only by violins in unison and basses; while Bach very frequently accompanies his airs with one solo instrument, either wind or stringed, and the basses. In such cases it is sometimes sufficient merely to add an inner part; at other times a somewhat fuller score is more effective. The following quotations will furnish examples of both methods.

Handel, 'Sharp violins proclaim.' (Ode for St. Cecilia's Day.)

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\time 4/4

<< { \clef treble \key a \major \relative c''

{ r4^\markup { \italic Viol. 1, 2 } r8 e cis16.\trill([ b32 cis8)] b16.\trill([ a32 b8)] |

a16.\trill[ gis32 a8] r e' fis16\trill e fis4 gis8 |

a16[ gis a8\trill] a,[ gis'] fis[ e d cis] | b } }

\new Staff

{ \clef bass \key a \major \relative c'

{ a4^\markup { \italic Bassi } gis a e | fis cis d8 cis b e | a, b cis a d cis b a | e' } }

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/s/dshvl4m1c8buhfzh95dv93jc2uyb2t5/dshvl4m1.png)

Ditto (Mozart).

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\time 4/4

<< { \clef treble \key a \major \relative c''

{ r4^\markup { \italic Viol. 1, 2 } r8 e cis16.\trill([ b32 cis8)] b16.\trill([ a32 b8)] |

a16.\trill[ gis32 a8] r e' fis16\trill e fis4 gis8 |

a16[ gis a8\trill] a,[ gis'] fis[ e d cis] | b } }

\new Staff

{ \clef alto \key a \major \relative c'

{ cis4^\markup { \italic Viola } b e d | cis a( a8) d4 cis16 b | cis8 d e cis d[ e] fis16[ gis a8] | gis } }

\new Staff

{ \clef bass \key a \major \relative c'

{ a4^\markup { \italic Bassi } gis a e | fis cis d8 cis b e | a, b cis a d cis b a | e' } }

>>

}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/t/ltozoq21bsi66cnjs3r0odqp0urdtgt/ltozoq21.png)

Handel, 'I know that my Redeemer liveth.' (Messiah.)

Ditto (Mozart.)

Bach, 'Ich hatte viel Bekümmerniss.'

Ditto (Franz).

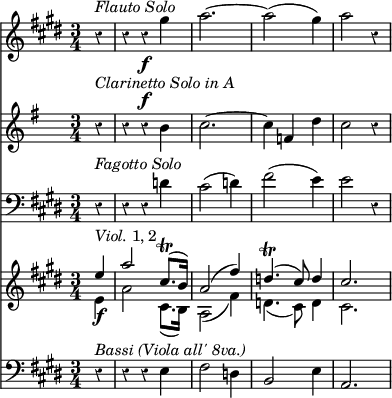

In the first of these extracts nothing is added but a viola part; in the second Mozart has doubled the first violins by the second in the lower octave, and assigned a full harmony to the three solo wind instruments, while in the third Franz has added the string quartett to the solo oboe, and again treated the parts in that polyphonic style which experience has taught him is alone suitable for the fitting interpretation of Bach's ideas.

5. In all the cases hitherto treated, the melody being given as well as the bass, the task of the editor is comparatively easy. It is otherwise however when (as is sometimes found with Handel, and still more frequently with Bach) nothing whatever is given excepting a bass, especially if, as often happens, this bass is not even figured. In the following quotation, for example, taken from Bach's 'Magnificat' ('Quia fecit mini magna'),

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \key a \major \time 4/4 \clef bass \relative c' { r4 a8[ a] a[ gis16 a] a8[ d,] | cis4 cis'8[ cis] cis[ b16 cis] d8[ fis,] | e4 cis'8 e, d4 b'8 d, | cis4 a'16[ gis fis e] d[ cis b a] e'8 e, | a8 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/p/cp0xr1c928kcqqxjwl6y1ai1gwavydt/cp0xr1c9.png)

it is obvious that if nothing but the bass part be played, a mere caricature of the composer's intentions will be the result. Here there are no figures in the score to indicate even the outline of the harmony. The difficulties presented by such passages as these have been overcome in the most masterly manner by Robert Franz, who fills up the score thus—

By comparing the added parts (which, to save space, are given only in compressed score) with the original bass, it will be seen that they are all founded on suggestions thrown out, so to speak, by Bach himself, on ideas indicated in the bass, and it is in obtaining unity of design by the scientific employment of Bach's own material that Franz shows himself so well fitted for his self-imposed labour. It has been already said that Bach requires more polyphonic treatment of the parts than Handel. The following extract from Franz's score of 'L'Allegro' ('Come, but keep thy wonted state') will show the different method in which he fills up a figured bass in Handel's music. The original stands thus—

which Franz completes in this manner—

Here it will be seen there is no attempt at imitative writing. Nothing is done beyond harmonising Handel's bass in four parts. The harmonies are given to clarinets and bassoons in order that the first entry of the strings, which takes place in the third bar, may produce the contrast of tone-colour designed by the composer.

6. It is quite impossible within the limits of such an article as the present to deal exhaustively with the subject in hand; enough has, it is hoped, been said to indicate in a general manner some of the various ways of filling up the orchestration from a figured bass. This however, though perhaps the most important, is by no means the only case in which additional accompaniments are required or introduced. It was mentioned above that the composition of the orchestra in the days of Bach and Handel was very different from that of our own time. This is more especially the case with Bach, who employs in his scores many instruments now altogether fallen into disuse. Such are the viola d'amore, the viola da gamba, the oboe d'amore, the oboe da caccia (which he sometimes calls the 'taille'), and several others. In adapting these works for performance, it is necessary to substitute for these obsolete instruments as far as possible their modern equivalents. Besides this, both Handel and Bach wrote for the trumpets passages which on the instruments at present employed in our orchestras are simply impossible. Bach frequently, and Handel occasionally, writes the trumpet parts up to C in alt, and both require from the players rapid passages in high notes, the execution of which, even where possible, is extremely uncertain. Thus, in probably the best-known piece of sacred music in the world, the Hallelujah chorus in the 'Messiah,' Handel has written D in alt for the first trumpet, while Bach in the 'Cum Sancto Spiritu' of his great Mass in B minor has even taken the instrument one note higher, the whole first trumpet part as it stands being absolutely unplayable. In such cases as these it becomes necessary to re-write the trumpet parts, giving the higher notes to some other instrument. This is what Franz has done in his editions of Bach's 'Magnificat' and 'Pfingsten-Cantate,' in which he has used two clarinets in C to reinforce and assist the trumpet parts. The key of both pieces being D, the clarinets in A would be those usually employed; the C clarinets are here used instead, because their tone, though less rich, is more piercing, and therefore approximates more closely to that of the high notes of the trumpet. One example from the opening chorus of the 'Magnificat' will show how the arrangement is effected. Bach's trumpet parts and their equivalents in Franz's score will alone be quoted.

Bach.

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 3/4 << \relative c'' { c2.^\markup { \smaller \italic "Tromba 1 in D" } ~ | c16 d c d e fis d e fis g e fis | g d e fis g a g a b c a b | c b a g a g fis e fis e d c | d8 c' b16 a g a a8.-\trill g16 | g8 d r4 r | b'8 g r4 r | d'8 b r4 r | }

\new Staff { \clef treble \relative c' { r8^\markup { \smaller \italic "Trombe 2, 3 in D." } <c g>[ <e c> <g e>] <c c,> r | r2. | r2. | r2. | << { r8 a' g16[ fis e fis] fis8.\trill[ d16] } \\ { r2. } >> | <d g,>8 <g, g,> r4 r | <g' d>8 <d g,> r4 r | <b' g>8 <g d> r4 r | } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/l/kl54hnmm9bujlvgfq7mqx9d9gcri9fc/kl54hnmm.png)

Franz.

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 3/4 \key d \major << \relative d'' { d2.^\markup { \smaller \italic "2 Clarinetti in C" } ~ | d16 e d e fis gis e fis g a fis g | a e fis gis a b a b cis d b cis | d cis b a b a gis fis gis fis e d | e8 <d' b> <cis a>16 <b gis> <a fis> <b gis> <b gis>8. a16 | a4 r r | <cis a>8 <a e> r4 r | <e' cis>8 <cis a> r4 r | }

\new Staff { \clef treble \relative c'' { << { c2.^\markup { \smaller \italic "3 Trombe in D" } } \\ { r8 <c, g>8[ <e c> <g e>] <c c,> r } >> | r2. | r | r | << { r4 r d8. d16 } \\ { r2 d8. d16 } >> | <g d g,>8 <d g, g,> r4 r | <g d g,>8 <d g, g,> r4 r | <g d g,>8 <d g, g,> r4 r | } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/c/cc8c73cqwwr8ekgg1ixbj3v9ixlkthk/cc8c73cq.png)

It is to be regretted that the same amount of reverence for the author's intentions shown in the above arrangement has not always been evinced even by great musicians in dealing with the scores of others. Mozart, in his arrangement of the 'Messiah,' thought fit to re-write the song 'The trumpet shall sound,' though whatever obstacle it may have presented to his trumpeter it has been often proved by Mr. Thomas Harper and others that Handel's trumpet part, though difficult, is certainly not impossible. Mendelssohn, in his score of the 'Dettingen Te Deum,' has altered (and we venture to think entirely spoilt) several of the very characteristic trumpet parts which form so prominent a feature of the work. As one example out of several that might be quoted, we give the opening symphony of the chorus 'To thee Cherubin.' Handel writes

These trumpet parts are assuredly not easy; still they are practicable. Mendelssohn however alters the whole passage thus:—

and, still worse, when the symphony is repeated in the original by oboes and bassoons, the arranger gives it to the full wind band with trumpets and drums, entirely disregarding the ideas of the composer. The chief objection to be urged against such a method of procedure as the above—so unlike Mendelssohn's usual reverence and modesty[2]—is not that the instrumentation is changed or added to, but that the form and character of the passage itself is altered. Every arrangement must stand or fall upon its own merits; but it will be generally admitted that however allowable it may be, nay more, however necessary it frequently is, to change the dress in which ideas are presented to us, the ideas themselves should be left without modification.

7. Besides the cases already referred to, passages are frequently to be found, especially in the works of Bach, in which, though no obsolete instruments are employed, and though everything is perfectly practicable, the effect, if played as written, will in our modern orchestras altogether differ from that designed by the composer. From a letter written by Bach in 1730[3] we know exactly the strength of the band for which he wrote. Besides the wind instruments, it contained only two or at most three first and as many second violins, two first and two second violas, two violoncellos and one double-bass, thirteen strings in all. Against so small a force the solo passages for the wind instruments would stand out with a prominence which in our modern orchestras, often containing from fifty to sixty strings, would no longer exist; and as all the parts in Bach's music are almost invariably of equal importance, it follows that the wind parts must be strengthened if the balance of tone is to be preserved. This is especially the case in the choruses. It would be impossible, without quoting an entire page of one of Bach's scores, to give an extract clearly showing this point. Those who are familiar with his works will recall many passages of the kind. One of the best known, as well as one of the most striking examples is in the short chorus 'Lass ihn kreuzigen' in the 'Passion according to Matthew.' Here an important counterpoint is given to the flutes above the voices and stringed instruments. With a very small band and chorus this counterpoint would doubtless be heard, but with our large vocal and instrumental forces it must inevitably be lost altogether. Franz, in his edition of the 'Passion,' has reinforced the flutes by the upper notes of the clarinets, which possess a great similarity of tone, and at the same time by their more incisive quality make themselves distinctly heard above the other instruments.

8. In Handel's orchestra the organ was almost invariably used in the choruses to support the voices, and give fullness and richness to the general body of tone. Hence in Mozart's arrangements, which were written for performance without an organ, he has supplied the place of that instrument by additional wind parts. In many of the choruses of the 'Messiah' (e.g. 'And the glory of the Lord,' 'Behold the Lamb of God,' 'But thanks be to God,' etc.) the wind instruments simply fill in the harmony as it may fairly be conjectured the organ would do. Moreover, our ears are so accustomed to a rich and sonorous instrumentation, that this music if played only with strings and oboes, or sometimes with strings alone, would sound so thin as to be distasteful. Hence no reasonable objection can be made to the filling up of the harmony, if it be done with taste and contain nothing inconsistent with the spirit of the original.

9. There yet remains to notice one of the most interesting points connected with our present subject. It not seldom happens that in additional accompaniments new matter is introduced for which no warrant can be found in the original. Sometimes the composer's idea is modified, sometimes it is added to. Mozart's scores of Handel are full of examples of this kind; on the other hand Franz, the most conscientious of arrangers, seldom allows himself the least liberty in this respect. It is impossible to lay down any absolute rule in this matter; the only test is success. Few people, for instance, would object to the wonderfully beautiful wind parts which Mozart has added to 'The people that walked in darkness,' though it must be admitted that they are by no means Handelian in character. It is, so to speak, Mozart's gloss or commentary on Handel's music; and one can almost fancy that could Handel himself have heard it he would have pardoned the liberty taken with his music for the sake of the charming effect of the additions. So again with the trumpets and drums which Mozart has introduced in the song 'Why do the nations.' No doubt Handel could have used them had he been so disposed; but it was not the custom of his age to employ them in the accompaniments to songs, and here again the excellence of the effect is its justification. On the same ground may be defended the giving of Handel's violin part to a flute in the air 'How beautiful are the feet,' though it is equally impossible to approve of the change Mozart has made in the air and chorus 'The trumpet's loud clangour' in the 'Ode to St. Cecilia's Day,' in, which he has given a great portion of the important trumpet part (which is imperatively called for by the words) to the flute and oboe in unison! The passages above referred to from the 'Messiah' are so well known as to render quotation superfluous; but two less familiar examples of happily introduced additional matter from the 'Ode to St. Cecilia's Day' will be interesting. In the first of these,

from the song 'Sharp violins proclaim,' it will be seen that Handel has written merely violins and basses. The dissonances which Mozart has added in the viola part,

are of the most excellent effect, well suited moreover to the character of the song which treats of 'jealous pangs and desperation.' Our last extract will be from the song 'What passion cannot music raise and quell?' in which Mozart has added pizzicato chords for the strings above the obligate part for the violoncello.

Handel.

Mozart.

[ E. P. ]

- ↑ See also Chrysander's 'Jahrbücher für Musikalische Wissenschaft,' Band I, which contains a long article on this subject.

- ↑ The Te Deum and Acis were instrumented by Mendelssohn as an exercise for Zelter. The date on the MS. of Acis is January 1829. He mentions them in a letter to Devrient in 1833, speaking of his additions to the Te Deum as 'Interpolations of a very arbitrary kind, mistakes as I now consider them, which I am anxious to correct.' It is a thousand pities that the work should have been published.

- ↑ See Bitter. 'Johann Sebastian Bach,' ii. 15-22.