A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Arrangement

ARRANGEMENT, or ADAPTATION, is the musical counterpart of literary translation. Voices or instruments are as languages by which the thoughts or emotions of composers are made known to the world; and the object of arrangement is to make that which was written in one musical language intelligible in another.

The functions of the arranger and translator are similar; for instruments, like languages, are characterised by peculiar idioms and special aptitudes and deficiencies which call for critical ability and knowledge of corresponding modes of expression in dealing with them. But more than all, the most indispensable quality to both is a capacity to understand the work they have to deal with. For it is not enough to put note for note or word for word or even to find corresponding idioms. The meanings and values of words and notes are variable with their relative positions, and the choice of them demands appreciation of the work generally, as well as of the details of the materials of which it is composed. It demands, in fact, a certain correspondence of feeling with the original author in the mind of the arranger or translator. Authors have often been fortunate in having other great authors for their translators, but few have written their own works in more languages than one. Music has had the advantage of not only having arrangements by the greatest masters, but arrangements by them of their own works. Such cases ought to be the highest order of their kind, and if there are any things worth noting in the comparison between arrangements and originals they ought to be found there.

The earliest things which answered the purpose of arrangements were the publications of parts of early operas, such as the recitatives and airs with merely figured bass and occasional indications of a figure or a melody for the accompaniment. In this manner were published operas of Lulli and Handel, and many now forgotten composers for the stage of their time and before; but these are not of a nature to arouse much interest.

The first arrangements which have any great artistic value are Bach's; and as they are many of them of his own works, there is, as has been before observed, especial reason for putting confidence in such conclusions as can be arrived at from the consideration of his mode of procedure. At the time when his attention was first strongly attracted to Italian instrumental music by the principles of form which their composers had originated, and worked with great skill, he arranged sixteen violin concertos of Vivaldi's for the clavier solo, and three of the same and a first movement for the organ. Of the originals of these it appears from Spitta[1] that there is only one [App. p.523 "there are six"] to be found for comparison; but, as Spitta observes, from the freedom with which Bach treated his original in this instance it is legitimate to infer his treatment of the others. Vivaldi's existing concerto is in G major, and is the basis of the second in Bach's series—in the game key (Dörffel, 442).[2] In form it is excellent, but its ideas are frequently crude and unsatisfactory, and their treatment is often thin and weak. Bach's object being rather to have good illustrations of beauty of form than substance, he did not hesitate to alter the details of figures, rhythms, and melodies, and even successions of keys, to amplify cadences, and add inner parts, till the whole is transformed into a Bach-commentary on the form-principles of the Italians rather than an arrangement in the ordinary meaning of the term. It is not however an instance to justify arrangers in like freedom, as it is obviously exceptional, and is moreover in marked opposition to Bach's arrangements of his own works.

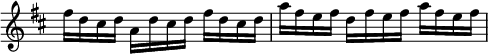

Some of these are of a nature to induce the expectation that the changes would be considerable; as for instance the arrangement of the prelude to the Solo Violin Sonata in E, as the introduction in D to the Cantata 'Wir danken dir Gott'[3] for obligato organ with accompaniment of strings oboes and trumpets. The original movement consists almost throughout of continually moving semiquavers embracing many thorough violin passages, and certainly does not seem to afford much material to support its changed condition. But a comparison shows that there is no change of material importance in the whole, unless an accompaniment of masterly simplicity can be called a change. There are immaterial alterations of notes here and there for the convenience of the player, and the figure

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \key e \major \relative g'' << { s16 e s8 s2 | s16 e } \\ { \repeat percent 3 { gis16[ s gis e] } | \repeat percent 3 { gis16[ s gis dis] } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/7/q75jz70lmlj3lkpliubma3yk32uqu6t/q75jz70l.png)

in the violin sonata, is changed into

in the organ arrangement and so on, for effect, and that is all.

Another instance of a like nature is the arrangement of the fugue from the solo violin sonata in G minor (No. 1) for Organ in D minor (Dörffel, 821). Here the changes are more important though still remarkably slight considering the difference between the violin and the two hands and pedals of an organ.

The most important changes are the following:—

The last half of bar 5 and the first of bar 6 are amplified into a bar and two halves to enable the pedals to come in with the subject in the orthodox manner.

In the same manner two half-bars are inserted in the middle of bar 28, where the pedal comes in a second time with a quotation of the subject not in the original. In bar 16 there is a similar point not in the original, which however makes no change in the harmony.

The further alterations amount to the filling up and wider distribution of the original harmonies, the addition of passing notes and grace notes, and the remodelling of violin passages; of the nature of all which changes the following bar is an admirable instance—

Two other arrangements of Bach's, namely that of the first violin concerto in A minor, and of the second in E major as concertos for the clavier in G minor and D major respectively (Dörffel, 600, 603; 564, 570), are not only interesting in themselves, but become doubly so when compared with Beethoven's arrangement of his violin concerto in D as a pianoforte concerto.[4]

The first essential in these cases was to add a sufficiently important part for the left hand, and the methods adopted afford interesting illustrations of the characteristics of the two great masters themselves, as well as of the instruments they wrote for. A portion of this requirement Bach supplies from the string accompaniment, frequently without alteration; but a great deal appears to be new till it is analysed; as, for instance, the independent part given to the left hand in the first movement of the concerto in G minor from the twenty-fifth bar almost to the end, which is as superbly fresh and pointed as it is smooth and natural throughout. On examination this passage—which deserves quotation if it were not too long—proves to be a long variation on the original bass of the accompaniment, and perfectly faithful to its source.

Bach's principle in this and in other cases of like nature is contrapuntal; Beethoven's is the exact contrary almost throughout. He supplies his left hand mainly with unisons and unisons disguised by various devices (which is in conformity with his practice in his two great concertos in G and E flat, in which the use of unisons and disguised unisons for the two hands is very extensive); and where a new accompaniment is inserted it is of the very simplest kind possible, such as

after the cadenza in the first movement; or else it is in simple chords, forming unobtrusive answers to figures and rhythms in the orchestral accompaniment.

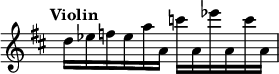

Both masters alter the original violin figures here and there for convenience or effect. Thus Bach, in the last movement of the G minor clavier concerto (Dörffel, 566), puts

for the violin figure

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 << \relative e'' { e16 s8. s8 e16 } \\ \relative e'' { s16 e[ c e] e8 s16 e[ c e] e8 | } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/b/lbp8canl8cxwtj1mumg8k6r7knz4urb/lbp8canl.png)

and in the last movement of the D major (Dörffel, 572) puts

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/8 \key d \major \relative b' { \times 2/3 { b16[ a g] } \override TupletNumber #'stencil = ##f \times 2/3 { fis[ a c] } \times 2/3 { b[ a g] } | cis![ e] g[ fis \override TupletBracket #'bracket-visibility = ##f \times 4/5 { e32 d cis b a] } | } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/6/26tf5cgp19wv7eozd1t072t2e3k07jt/26tf5cgp.png)

for

in the E major violin concerto.

The nature of Beethoven's alterations may be judged of from the following quotation from the last movement, after the cadenza:—

Another typical alteration is after the coda in the first movement, where, in the thirteenth bar from the end, in order to give the left hand something to do, Beethoven anticipates the figure of smoothly flowing semiquavers with which the part of the violin closes, making the two hands alternate till they join in playing the last passage in octaves. In both masters' works there are instances of holding notes being changed into shakes in the arrangements, as in the 7th and 8th bars of the slow movement of the D concerto of Bach, and the 2nd and 5th bars after the first tutti in the last movement of Beethoven's concerto. In both there are instances of simple devices to avoid rapid repetition of notes, which is an easy process on the violin, but an effort on the pianoforte, and consequently produces a different effect. They both amplify arpeggio passages within moderate bounds, both are alike careful to find a precedent for the form of a change when one becomes necessary, and in both the care taken to be faithful to the originals is conspicuous.

The same care is observable in another arrangement of Beethoven's, viz. the Pianoforte Trio[5] made from his second symphony.

The comparison between these is very interesting owing to the unflagging variety of the distribution of the orchestral parts to the three instruments. The pianoforte naturally takes the substance of the work, but not in such a manner as to throw the others into subordination. The strings are used mostly to mark special orchestral points and contrasts, and to take such things as the pianoforte is unfitted for. Their distribution is so free that the violin will sometimes take notes that are in the parts of three or more instruments in a single bar. In other respects the strings are used to reinforce the accompaniment, so that in point of fact the violin in the trio plays more of the second violin part than of the first, and the violoncello of any other instrument from basso to oboe than the part given to it in the symphony.

The changes made are few and only such as are necessitated by technical differences, and are of the same simple kind with those in the concerto, and originating in similar circumstances. Everything in the distribution of the instruments subserves some purpose, and the re-sorting of the details always indicates some definite principle not at variance with the style of the original.

An illustration of the highest order in more modern works is found in the exquisitely artistic arrangement of the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' music for four hands on one pianoforte by Mendelssohn himself.

The step from Beethoven to Mendelssohn embraces a considerable development of the knowledge of the technical and tonal qualities of the pianoforte, as well as of its mechanical improvement as an instrument. This becomes apparent in the different characteristics of Mendelssohn's work, which in matter of detail is much more free than Beethoven's, though quite as faithful in general effect.

At the very beginning of the overture is an instance in point, where that which appears in the score as

is in the pianoforte arrangement given as

the object evidently being to avoid the repetition and the rapid thirds which would mar the lightness and crispness and delicacy of the passage.

In one instance a similar effect is produced by a diametrically contrary process, where Bottom's bray, which in the original is given to strings and clarinets (a), is given in the pianoforte arrangement as at (b):—

It is to be remarked that the arrangement of the overture is written in notes of half the value of those of the orchestral score, with twice the amount in each bar; except the four characteristic wind-chords—tonic, dominant, sub-dominant, and tonic—which are semibreves, as in the original, whenever they occur; in all the rest semiquavers stand for quavers, quavers for crotchets, crotchets for minims, etc., as may be seen by referring to the above examples. The change may possibly have been made in the hope that the players would be more likely to hit the character of the work when playing from the quicker looking notes; or it may have been a vague idea of conforming to a kind of etiquette noticeable in music, church music affecting the longer looking notes, such as semibreves and minims, while orchestral music has the faster looking notes, such as quavers (overtures to 'Coriolan,' 'Leonore,' 'Fidelio,' 'Jessonda,' etc.), and pianoforte music descends to semiquavers—as though to mark the relative degrees of dignity.

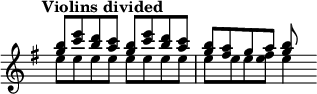

The pianoforte arrangement of the scherzo of the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' abounds with happy devices for avoiding rapid repetitions, and for expressing contrasts of wind and strings, and imitating the effect of many orchestral parts which it would be impossible to put into the arrangement in their entirety. One of the happiest passages in the whole work is the arrangement of the passage on the tonic pedal at the end of this movement.

(G pedal, pizzicati bassi, and Corni and Trombe on first beat of each bar.)

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/8 \key g \minor << << \relative g'' { g8^\markup { \italic Primo } s g-. | c,-. r c-. | f-. r f-. | bes,-. } \\ \relative d'' { r16 d[ c bes] g'[ b,] | r aes[ g aes] c[ aes] | r aes[ g aes] f'[ aes] | r } >>

\new Staff { \clef treble \key g \minor \relative g { g8^\markup { \italic "Secondo R. H." } r <bes d g> | <aes c> r <aes c> | <aes c f> r <aes c f> | a^\markup { \smaller etc. } } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/s/ts313cpk48oao4ekoo8z6z2y8snpn70/ts313cpk.png)

Mendelssohn often takes the freedom of slightly altering the details of a quick passage in order to give it greater interest as a pianoforte figure; which seems to be a legitimate development of the theory of the relative idiomatic modes of expression of different instruments, and its adaptation to details.

The method most frequently adopted by him to imitate the effect of the contrast of wind and strings in the same position, is to shift the figure or chords of one of them an octave higher or lower, and to give them respectively to the right and left hands, as in the first part of the music to the first scene of the second act. The continual alternation of the hands in the same position in the Intermezzo after the second act represents the alternation between violins and oboi, and clarinets and flutes.

In the music to the first scene of the third act an important drum roll is represented by a bass shake beginning on the semitone below the principal note, which is much happier than the usual method. In these respects Mendelssohn's principles of arrangement accord with those of Bach and Beethoven, differing only in those respects of treatment of detail which are the result of a more refined sense of the qualities of the pianoforte arising from the long and general cultivation of that instrument.

A still further development in this direction is found in the arrangement by Herr Brahms of his pianoforte quintett in F minor (op. 34) as a sonata for two pianofortes. In this the main object seems to have been to balance the work of the two pianofortes. Sometimes the first pianoforte, and sometimes the second has the original pianoforte part for pages together, and sometimes for a few bars at a time, but whenever the nature of the passages admits of it, the materials are distributed evenly between the two instruments. There are some changes—such as the addition of a bar in two places in the first movement, and the change of an accidental in the last—which must be referred to critical considerations, and have nothing to do with arrangement.

The technical changes in the arrangement are the occasional development of a free inner part out of the materials of the original without further change in the harmonies, the filling up of rhythm-marking chords of the strings, frequent reinforcement of the bass by doubling, and, which is especially noticeable, frequent doubling of both melodies and parts of important figures. It is this latter peculiarity which especially marks the adaptation of certain tendencies of modern pianoforte-playing to arrangement,—the tendency, namely, to double all the parts possible, to fill up chords to the utmost, and to distribute the notes over a wider space, with greater regard to their tonal relations than formerly, and by every means to enlarge the scope and effective power of the instrument, at the same time breaking down all the obstructions and restrictions which the old dogmas of style in playing placed in the way of its development.

Another admirable instance of this kind is the arrangement by Herr Brahms of a gavotte of Gluck's in A; which however in its new form is as much marked by the personality of the arranger as that of the composer—a dangerous precedent for ordinary arrangers.

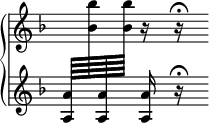

The most remarkable instance of the adaptation of the resources of modern pianoforte-playing to arrangement, is that by Tausig of Bach's toccata and fugue for the organ in D, 'zum Conzertvortrag frei bearbeitet.' The difficulty in such a case is to keep up the balance of the enlarged scale throughout. Tausig's perfect mastery of his art has carried him through the ordeal unscathed, from the first bar, where

down to the end, where Bach's

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \new StaffGroup \time 3/4 \partial 4 << \new Staff = "up" { \key d \minor \relative c'' << { c4 | cis8 s16. a32 cis8_\markup { \smaller etc. } } \\ \relative g' { r8 <g e c> | <a e> \change Staff = "down" a,32[ \change Staff = "up" cis e] } >> }

\new Staff = "down" { \clef bass \key d \minor \relative g { r8 g a s r } }

\new Staff = "pedal" { \clef bass \key d \minor \relative e { r8 e | g r r } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/l/4l4mobyeta9seejx1wqu1vaj1rtlkbr/4l4mobye.png)

becomes

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \new StaffGroup \time 3/4 \partial 8

<< \new Staff = "up" { \key d \minor \relative c'

{ <c e g c>8 | <cis e a cis> \times 8/10 { \change Staff = "down" \stemUp a,32([ cis e a

\change Staff = "up" \stemDown cis e g cis

\change Staff = "down" \stemUp \clef treble e a)] }

\change Staff = "up" r8_\markup { \smaller etc.; } } }

\new Staff = "down" \with { \consists "Span_arpeggio_engraver" } { \clef bass \set Staff.connectArpeggios = ##t \key d \minor

<< \relative c { <c e g>8\arpeggio | <cis e a> s4 cis'''4 } \\ \relative c, { <c c,>8\arpeggio | <g' g,>\arpeggio } >>

} >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/o/8ohtjntvrwkj17jquk42d9k8bsbykfs/8ohtjntv.png)

and the result in the hands of a competent performer is magnificent.

The point which this arrangement has in common with the foregoing classical examples, is its remarkable fidelity to the materials of the original, and the absence of irrelevant matter. The tendency of high class modern arrangements is towards freedom of interpretation; and the comparison of classical arrangements with their originals shows that this is legitimate, up to the point of imitating the idioms of one instrument by the idioms of another, the effects of one by the effects of another. Beyond that lies the danger of marring the balance of the original works by undue enlargement of the scale of particular parts, of obscuring the personality of the original composer, and of caricature, that pitfall of ill-regulated admiration, instances of which may be found in modern 'transcriptions,' which are the most extreme advance yet achieved in the direction of freedom of interpretation.

The foregoing is very far from exhausting the varieties of kinds of arrangement; for since these are almost as numerous as the possible interchanges between instruments and combinations of instruments, the only course open is to take typical instances from the best sources to illustrate general principles—and these will be found to apply to all arrangements which lay claim to artistic merit. To take for instance an arrangement of an orchestral work for wind band:—the absent strings will be represented by an increased number of clarinets of different calibres and corni di bassetto, and by the bassoons and increased power of brass. But these cannot answer the purpose fully, for the clarinets cannot take the higher passages of the violin parts, and they will not stand in an equally strong degree of contrast to the rest of the band. Consequently the flutes have to supplement the clarinets in places where they are deficient, and the parts originally belonging to them have to be proportionately modified; and in order to meet the requirements of an effect of contrast, the horns, trombones, etc. for lower parts, have to play a great deal more than in the original, both of melody and accompaniment. The part of the oboes will probably be more similar than any other, though it will need to be modified to retain its relative degree of prominence in the band. On the whole a very general interchange of the parts of the instruments becomes necessary, which is done with due respect to the peculiarities of the different instruments, both as regards passages and relative tone qualities, in such a manner as not to mar the relevancy and balance of parts of the whole work.

Of arrangements of pianoforte works for full orchestra, of which there are a few modern instances, it must be said that they are for the most part unsatisfactory, by reuson of the marked difference of quality between pianoforte and orchestral music. It is like trying to spread out a lyric or a ballad over sufficient space to make it look like an epic. Of this kind are the arrangements of Schumann's 'Bilder aus Osten' by Reinecke, and Raff's 'Abends' by himself. Arrangements of pianoforte accompaniments are more justifiable, and Gounod's 'Meditation' on Bach's Prelude in C, Liszt's scoring of the accompaniment to Schubert's hymn 'Die Allmacht,' and his development of an orchestral accompaniment to a Polonaise of Weber's out of the materials of the original, without marring the Weberish personality of the work, are both greatly to the enhancement of the value of the works for concert purposes. The question of the propriety of eking out one work with portions of another entirely independent one—as Liszt has done in the Introduction to his version of this Polonaise—belongs to what may be called the morale of arrangement, and need not be touched upon here. Nor can we notice such adaptations as that of Palestrina's 'Missa Papæ Marcelli'—originally written for 6 voices—for 8 and 4, or that by the late Vincent Novello of Wilbye's 3-part madrigals for 5, 6, and 7 voices.

As might be anticipated, there are instances of composers making very considerable alterations in their own works in preparing them for performance under other conditions than those for which they were originally written, such as the arrangement, so-called, by Beethoven himself of his early Octett for wind instruments in E♭ (op. 103) as a quintett for strings in the same key (op. 4) and Mendelssohn's edition of the scherzo from his Octett in E♭ (op. 20) for full orchestra, introduced by him into his symphony in C minor—which are rather new works founded on old materials than arrangements in the ordinary sense of the term. They are moreover exceptions even to the practice of composers themselves, and do not come under the head of the general subject of arrangement. For however unlimited may be the rights of composers to alter their own works, the rights of others are limited to redistribution and variation of detail; and even in detail the alterations can only be legitimate to the degree which is rendered indispensable by radical differences in the instruments, and must be such as are warranted by the quality, proportions, and style of the context.

It may be convenient to close this article with a list of adaptations of their own works by the composers themselves, as far as they can be ascertained:—

1. Bach's arrangements of his own works are numerous. Some of them have already been noticed, but the following is a complete list of those indicated in Dörffel's Thematic Catalogue.

Concerto in F for clavier and two flutes with 4tett acct. (D. 561-3), appears also in G as concerto for violin and two flutes with 5tett acct (D. 1072-4).—Concerto in G minor for clavier with 5tett acct. (D. 564), as concerto in A minor for violin with 4tett acct. (D. 600).—Concerto in D major for clavier with 4tett acct. (D. 570), as concerto for violin in E major with 4tett acct. (D. 603).—The Prelude and Fugue in A minor for clavier solo (D. 400, 401), appears, with much alteration, as 1st and 3rd movements of concerto for clavier, flute, and violin in same key, with 5tett acct. (D. 582, 584). The slow movement of the same concerto, in C (D. 583), is taken from the third organ sonata, where it stands in F (D. 774).—The fugue in G minor for violin solo, from Sonata 1 (D. 610) appears in D minor, arranged for the organ (D. 821).—Sonata 3 for violin solo in A minor (D. 621-4), appears in D minor for clavier solo (D. 108–11).—The prelude in E for violin solo to Sonata 6 (D. 634) is arranged for organ and full orchestra in D, as 'sinfonia' to the Rathswahl cantata 'Wir danken dir, Gott,' No. 29 of the Kirchencantaten of the Bachgesellschaft (vol. v. 1), and the first movement of the 5th Sonata for Violin in C (D. 630) appears as a separate movement for Clavier in G (D. 141).—The first movement of the Concerto in E for Clavier appears in the Introduction to the Cantata 'Gott soll allein'; and the two first movements of the Concerto in D minor appear in the Cantata 'Wir müssen durch viel Trübsal.'

2. Handel was very much in the habit of using up the compositions both of himself and others, sometimes by transplanting them bodily from one work to another—as his own Allelujahs from the Coronation Anthems into 'Deborah,' or Kerl's organ Canzona, which appears nearly note for note as 'Egypt was glad' in 'Israel in Egypt'; and sometimes by conversion, as in the 'Messiah,' where the Choruses 'His yoke' and 'All we' are arranged from two of his own Italian Chamber duets, or in 'Israel in Egypt' where he laid his organ Fugues and an early Magnificat under large contribution. In other parts of 'Israel,' and in the 'Dettingen Te Deum' he used the music of Stradella and Urio with greater or less freedom. But these works come under a different category from those of Bach, and will be better examined under their own heads. More to the present purpose are his adaptations of his Orchestral works, such as the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th of the 2nd Set of Organ Concertos, which are mere adaptations of the 11th, 12th, 1st, and 6th of the 12 Concerti Grossi (op. 6). No. 1 of the same set of Organ Concertos is partly adapted from the 6th Sonata or Trio (op. 5).

3. Beethoven. The arrangements of the seventh and eighth symphonies for two hands, published by Steiner at the same time with the scores, although not by Beethoven himself, were looked through and corrected by him. He arranged the Grand Fugue for String Quartett (op. 133) as a duet for Piano. No other pianoforte arrangements by him are known; but he is said to have highly approved of those of his symphonies by Mr. Watts. Beethoven however rearranged several of his works for other combinations of instruments than those for which he originally composed them. Op. 1, No. 3, pianoforte trio, arranged as string quintett (op. 104). Op. 4, string quintett (two violins), arranged from the octett for wind instruments (1796), published later as op. 103. Op. 14, No. 1, pianoforte sonata in E, arranged as a string quartett in F. Op. 16, quintett for pianoforte and wind instruments, arranged as a pianoforte string quartett. Op. 20, the Septett, arranged as a trio for pianoforte, clarinet or violin, and cello (op. 38). Op. 36, symphony No. 2, arranged as a pianoforte trio. Op. 61, violin concerto, arranged as pianoforte concerto. The above are all that are certainly by Beethoven. Op. 31, No. 1, Pianoforte Sonata—G, arranged as a string quartett, is allowed by Nottebohm to be probably by the composer. So also were Op. 8, Notturno for String Trio arranged for Pianoforte and Tenor (op. 42), and Op. 25, Serenade for Flute, Violin, and Tenor, arranged for Pianoforte and Flute (op. 41), were looked over and revised by him.

4. Schubert. Arrangement for four hands of overture in C major 'in the Italian style' (op. 170), overture in D major, and overture to 'Rosamunde'; and for two hands of the accompaniments to the Romance and three choruses in the same work. The song 'Der Leidende' (Lief. 50, No. 2), in B minor, is an arrangement for voice and piano of the second trio (in B♭ minor') of the second Entracte of 'Rosamunde.'

5. Mendelssohn. For four hands: the Octett (op. 20); the 'Midsummer's Night's Dream' overture and other music; the 'Hebrides' overture; the overture for military band (op. 24); the andante and variations in B♭ (op. 83 a), originally written for two hands. For two hands: the accompaniments to the Hochzeit des Camacho, and to the 95th Psalm (op. 46). He also arranged the scherzo from the string octett (op. 20) for full orchestra to replace the minuet and trio of his symphony in C minor on the occasion of its performance by the Philharmonic Society, as noticed above.

6. Schumann. For four hands : Overture, scherzo, and finale; Symphony No. 2 (C major); Overture to 'Hermann und Dorothea.' Madame Schumann has arranged the quintett (op. 44) for four hands, and the accompaniments to the opera of 'Genoveva' for two hands.

7. Brahms has arranged Nos. 1, 3, and 6 of his 'Ungarische Tanze,' originally published as piano pieces for four hands, for full orchestra. He has also arranged his piano string quintett (op. 34) as a 'Sonata' for four hands on two pianos, and his two Orchestral Serenades for Piano, a quatre mains.[ C. H. H. P. ]

- ↑ Johann Sebastian Bach, von Philipp Spitta, vol. 1. p. 410 (Breitkopf, 1878).

- ↑ This and similar references are to the Thematic Catalogue of Bach's published instrumental works by Alfred Dörfell (Peters, 1867)

- ↑ Leipzig Bachgessellschaft, Cantata 29 (Vol v. No 5).

- ↑ Breitkopf's edition of Beethoven, No. 73.

- ↑ Breitkopf's edition of Beethoven, No. 90.