A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Harmony

HARMONY. The practice of combining sounds of different pitch, which is called Harmony, belongs exclusively to the music of the most civilised nations of modern times. It seems to be sufficiently proved that the ancient Greeks, though they knew the combinations which we call chords and categorised them, did not make use of them in musical performance. This reticence probably arose from the nature of their scales, which were well adapted for the development of the effective resources of melody, but were evidently inadequate for the purposes of harmony. In looking back over the history of music it becomes clear that a scale adapted for any kind of elaboration of harmony could only be arrived at by centuries of labour and thought. In the search after such a scale experiment has succeeded experiment, those which were successful serving as the basis for further experiments by fresh generations of musicians till the scale we now use was arrived at. The ecclesiastical scales, out of which our modern system was gradually developed, were the descendants of the Greek scales, and like them only adapted for melody, which in the dark ages was of a sufficiently rude description. The people's songs of various nations also indicate characteristic scales, but these were equally unfit for purposes of combination, unless it were with a drone bass, which must have been a very early discovery. In point of fact the drone bass can hardly be taken as representing any idea of harmony proper; it is very likely that it originated in the instruments of percussion or any other form of noise-making invention which served to mark the rhythms or divisions in dancing or singing; and as this would in most cases (especially in barbarous ages) be only one note, repeated at whatever pitch the melody might be, the idea of using a continuous note in place of a rhythmic one would seem naturally to follow; but this does not necessarily imply a feeling for harmony, though the principle had certain issues in the development of harmonic combinations, which will presently be noticed. It would be impossible to enter here into the question of the construction and gradual modification of the scales. It must suffice to point out that the ecclesiastical scales are tolerably well represented by the white notes of our keyed instruments, the different ones commencing upon each white note successively, that commencing on D being the one which was more commonly used than the others. In these scales there were only two which had a leading note or major seventh from the tonic. Of these the one beginning on F (the ecclesiastical Lydian) was vitiated by having an augmented fourth from the Tonic, and the one commencing on C (the ecclesiastical Ionic, or Greek Lydian) was looked upon with disfavour as the 'modus lascivus.' These circumstances affected very materially the early ideas of harmony; and it will be seen that, conversely, the gradual growth of the perception of harmonic relations modified these ecclesiastical scales by very slow degrees, by the introduction of accidentals, so that the various modes were by degrees fused into our modern major and minor scales.

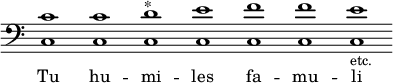

The earliest attempts at harmony of which there are any examples or any description, was the Diaphony or Organum which is described by Hucbald, a Flemish monk of the tenth century, in a book called 'Enchiridion Musicæ.' These consist for the most part of successions of fourths or fifths, and octaves. Burney gives an example from the work, and translates it as follows:—

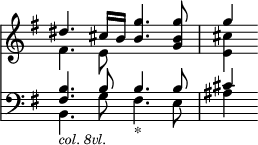

The practice of adding extra parts to a Canto fermo at the distance of a fourth or fifth, with an octave to make it complete, seems to have been common for some time, and was expressed by such terms as 'diatessaronare,' or in French 'quintoier.' This however was not the only style of combination known to Hucbald, for in another example which consists chiefly of successions of fifths and octaves the parallelism is interrupted at the close, and the last chord but one contains a major sixth. Further than this, Burney gives an example in which the influence of a drone bass or holding note is apparent, whereby the origin of passing notes is indicated, as will be observed in the use of a ninth transitionally between the combinations of the octave and the tenth in the following example at *.

The use of tenths in this example is remarkable, and evidently unusual, for Guido of Arezzo, who lived full a century later, speaks of the 'symphonia vocum' in his Antiphonarium, and mentions only fourths, fifths, and octaves. This might be through Hucbald's notions of combination being more vague than those of Guido, and his attempts at harmony more experimental; for, as far as can be gathered from the documents, the time which elapsed between them was a period of gradual realisation of the qualities of intervals, and not of progress towards the use of fresh ones. Guide's description of the Organum is essentially the same as the succession of fourths and fifths given by Hucbald; he does not however consider it very satisfactory, and gives an example of what was more musical according to his notions; but as this is not in any degree superior to the second example quoted from Hucbald above, it is clear that Guido's views on the subject of Harmony do not demand lengthy consideration here. It is only necessary to point out that he seems to have more defined notions as to what is desirable and what not, and he is remarkable also for having proposed a definition of Harmony in his Antiphonarium in the following terms—'Armonia est diversarum vocum apta coadunatio.'

The Diaphony or Organum above described was succeeded, perhaps about Guido's time, by the more elaborate system called Discantus. This consisted at first of manipulation of two different tunes so as to make them tolerably endurable when sung together. Helmholtz suggests that 'such examples could scarcely have been intended for more than musical tricks to amuse social meetings. It was a new and amusing discovery that two totally independent melodies might be sung together and yet sound well.' The principle was however, early adopted for ecclesiastical purposes, and is described under the name Discantus by Franco of Cologne, who lived but little after Guido in the eleventh century. From this Discantus sprang counterpoint and that whole genus of polyphonic music, which was developed to such a high pitch of perfection between the 14th and the 17th centuries; a period in which the minds of successive generations of musicians were becoming unconsciously habituated to harmonic combinations of greater and greater complexity, ready for the final realisation of harmony in and for itself, which, as will be seen presently, appears to have been achieved about the year 1600. Franco of Cologne, who as above stated describes the first forms of this Descant, is also somewhat in advance of Guido in his views of harmony. He classifies concords into perfect, middle, and imperfect consonances, the first being the octaves, the second the fourths and fifths, and the third the major and minor thirds. He puts the sixths among the discords, but admits of their use in Descant as less disagreeable than flat seconds or sharp fourths, fifths, and sevenths. He is also remarkable for giving the first indication of a revulsion of feeling against the system of 'Organising' in fifths and fourths, and a tendency towards the modern dogma against consecutive fifths and octaves, as he says that it is best to mix imperfect concords with perfect concords instead of having successions of imperfect or perfect.

It is unfortunate that there is a deficiency of examples of the secular music of these early times, as it must inevitably have been among the unsophisticated geniuses of the laity that the most daring experiments at innovation were made; and it would be very interesting to trace the process of selection which must have unconsciously played an important part in the survival of what was fit in these experiments, and the non-survival of what was unfit. An indication of this progress is given in a work by Marchetto of Padua, who lived in the 13th century, in which it appears that secular music was much cultivated in Italy in his time, and examples of the chromatic progressions which were used are given; as for instance—

Marchetto speaks also of the resolutions of Discords, among which he classes fourths, and explains that the part which offends the ear by one of these discords must make amends by passing to a concord, while the other part stands still. This classification of the fourth among discords, which here appears for the first time, marks a decided advance in refinement of feeling for harmony, and a boldness in accepting that feeling as a guide in preference to theory. As far as the ratios of the vibrational numbers of the limiting sounds are concerned, the fourth stands next to the fifth in excellence, and above the third; and theoretically this was all that the mediæval musicians had to guide them. But they were instinctively choosing those consonances which are represented in the compound tone of the lower note, that is in the series of harmonics of which it is the prime tone, or 'generator,' and among these the fourth does not occur; and they had not yet learnt to feel the significance of inversions of given intervals; and therefore the development of their perception of harmonies, dealing as yet only with combinations of two different notes at a time, would lead them to reject the fourth, and put it in the category of discordant intervals, in which it has ever since remained as far as contrapuntal music is concerned, while even in harmonic music it canno be said to be at all on an equality with other consonances.

The next writer on music of any prominent importance after Marchetto was Jean de Muris who lived in the 14th century. In his 'Ars Contrapuncti' he systematises concords, as the previous writers had done, into perfect and imperfect; but his distribution is different from Franco's, and indicates advance. He calls the octave and the fifth the perfect, and the major and minor thirds and major sixths the imperfect concords. The minor sixth he still excludes. Similarly to Franco he gives directions for intermingling the perfect and imperfect concords, and further states that parts should not ascend or descend in perfect concords, but that they may in imperfect. It is clear that individual caprice was playing a considerable part in the development of musical resources in de Muris's time, as he speaks with great bitterness of extempore descanters. He says of this new mode of descanting, in which they professed to use new consonances, 'O magnus abusus, magna ruditas, magna bestialitas, ut asinus sumatur pro homine, capra pro leone,' and so on, concluding, 'sic enim concordiæ confunduntur cum discordiis ut nullatenus una distinguatur ab aliâ.' Such wildness may be aggravating to a theorist, but in early stages of art it must be looked upon with satisfaction by the student who sees therein the elements of progress. Fortunately, after de Muris's time, original examples begin to multiply, and it becomes less necessary to refer to reporters for evidence, as the facts remain to speak for themselves. Kiesewetter gives an example of four-part counterpoint by Dufay, a Netherlander, who was born about 1360. This is supposed to be the earliest example of its kind extant, and is a very considerable advance on anything of which there is any previous account or existing examples, as there appears in it a frequent use of what we call the complete common chord with the third in it, and also its first inversion; and in technical construction especially it shows great advance in comparison with previous examples, and approaches much nearer to what we should call real music. It requires to be noted moreover that this improvement in technical construction is the most striking feature of the progress of music in the next two centuries, rather than any large extension of the actual harmonic combinations.

The works of Ockeghem, who lived in the next century to Dufay, do not seem to present much that is worthy of remark as compared with him. He occasionally uses suspended discords in chords of more than two parts, as—

from a canon quoted by Burney; but discords are of rare occurrence in his works, as they are also in those of his great pupil Josquin de Prés. For instance, in the first part of the Stabat Mater by the latter (in the Raccolta Generale delle Opere Classiche, edited by Choron), there are only ten examples of such discords in the whole eighty-eight bars, and it is probable that this was a liberal supply for the time when it was written.

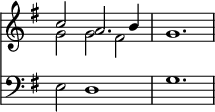

Ambros says that Josquin was the first to use accidentals to indicate the modifications of notes, which we are tolerably certain must have been modified according to fixed rules before his time without actual indication in the copies. Josquin certainly made use of them also to obtain effects which could not have been derived from the ordinary principles of rendering the music, and thus took an important step in the direction of assimilating the ecclesiastical scales in the manner which gradually resulted in the musical system we now use. A remarkable instance of this is his use more than once of a concluding chord with a major third in it, the major third being indicated by an accidental. Prior to him the concluding chord had contained only a bare fifth at most, and of this there are examples in his works also, as—

from the Benedictus of the Mass 'Faysans regrets' quoted by Burney (ii. 500)—in which progression the use of the E♭ is worthy of notice; but his use of the major third shows a remarkable advance, especially in the direction of feeling for tonality, which is one of the essential features of modern music.

This use of the major third in the final chord of a piece in a minor key became at a latter time almost universal, the only alternative being bare fifth, as in the last example; and the practice was continued far on into modern music; as by Bach and Handel, in the former of whose works it is very common even in instrumental music. And still later we find it in Mozart, at the end of the 'Quam olim Abrahæ' in the Requiem Mass. On the other hand, at the conlusion of the Chorus 'Dies Iræ' of the same mass the final chord appears, as far as the voices are concerned, with only a fifth in it, as in the example from Josquin above. However with composers of the harmonic period such as these t has not been at all a recognized rule to avoid be minor third in the final chord, its employment avoidance being rather the result of characteristic qualities of the piece which it concludes. But with composers of the preharmonic period it was clearly a rule; and its origin depended on the same feeling as that which caused them to put the fourth in the category of the discords; for like the fourth, the minor third does not exist as a part of the compound tone of the lower note, and its quality is veiled and undefined; and it was not till a totally new way of looking at music came into force that it could stand on its own basis as final; for among other considerations, the very vagueness of tonality which characterised the old polyphonic school necessitated absolute freedom from anything approaching to ambiguity or vagueness in the concluding combination of sounds. In modern music the passage preceding the final cadence is likely to be all so consistently and clearly in one key, that the conclusion could hardly suffer in definition by the use of the veiled third; but if the following beautiful passage from the conclusion of Josquin's 'Deploration de Jehan Okenheim' be attempted with a minor third instead of his major third for the conclusion, the truth of these views will be more strongly felt than after any possible argument:—

In this case it is quite clear that a minor third would not seem like any conclusion at all; even the bare fifth would be better, since at least the harmonic major third of the three A's would sound unembarassed by a contiguous semitone, for each of the A's in the chord would have a tolerably strong harmonic C♯, with which the presence of a C♮ would conflict. But the major third has in this place a remarkable finality, without which the preceding progressions, so entirely alien to modern theories of tonality, would be incomplete, and, as it were, wanting a boundary line to define them.

This vagueness of tonality, as it is called, which is so happily exemplified in the above example, especially in the 'Amen,' is one of the strongest points of external difference between the mediæval and modern musical systems. The vagueness is to a great extent owing to the construction of the ecclesiastical scales, which gives rise to such peculiarities as the use of a common chord on the minor seventh of the key, as in the following example from Bird's Anthem, 'Bow thine ear,' where at * there is a common chord on E♭ in a passage which in other respects is all in the key of F major.

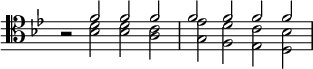

But the actual and vital difference between the two systems lay in the fact that the old musicians regarded music as it were horizontally, whereas the moderns regard it perpendicularly. The former looked upon it and taught it in the sense of combined voice parts, the harmonic result of which was more or less a matter of indifference; but the latter regard the series of harmonies as primary, and base whole movements upon their interdependent connection, obtaining unity chiefly by the distribution of the keys which throws those harmonies into groups. In the entire absence of any idea of such principles of construction, the mediævalists had to seek elsewhere their bond of connection, and found it in Canonic imitation, or Fugue, though it must be remembered that their idea of Fugue was not of the elaborate nature denoted by the term at the present day. As an example of this Canonic form, the famous secular song, 'Sumer is icumen in,' will serve very well; and as it is printed in score in both Burney's and Hawkins's Histories, it will be unnecessary to dwell upon it here, since its harmonic construction does not demand special notice. In all such devices of Canon and Fugue the great early masters were proficients, but the greatest of them were not merely proficient in such technicalities, but were feeling forward towards things which were of greater importance, namely, pure harmonic effects. This is noticeable even as early as Josquin, but by Palestrina's time it becomes clear and indubitable. On the one hand, the use of note against note counterpoint, which so frequently occurs in Palestrina's works, brings forward prominently the qualities of chords; and on the other, even in his polyphony it is not uncommon to meet with passages which are as clearly founded on a simple succession of chords as anything in modern music could be. Thus the following example from the motet, 'Hæc dies quam fecit Dominus'—

is simply an elaboration of the progression:—

In fact, Palestrina's success in the attempt to revivify Church Music lay chiefly in the recognition of harmonic principles; and in many cases this recognition amounts to the use of simple successions of chords in note against note counterpoint, as a contrast to the portion of the work which is polyphonic. His success also depended to a great degree on a very highly developed sense for qualities of tone in chords arising from the distribution of the notes of which they are composed. He uses discords more frequently than his predecessors, but still with far greater reticence than a modern would do; and in order to obtain the necessary effects of contrast, he uses chords in various positions, such as give a variety of qualities of softness or roughness. This question, which shows to what a high degree of perfection the art was carried, is unfortunately too complicated to be discussed here, and the reader must be referred to part ii. chap. 12 of Helmholtz's work on the 'Sensations of Tone as a physiological basis for the theory of Music,' where it is completely investigated. As an example of the freedom with which accidentals were used in secular music in Palestrina's time may be taken the following passage from a madrigal by Cipriano Bore, which is quoted by Burney (Hist. iii. 319):—

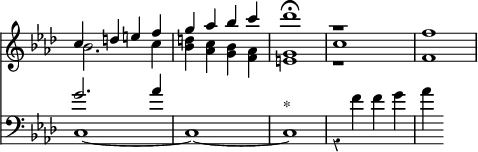

It will have been remarked from the above survey, that from the dawn of any ideas of combination of notes, musicians were constantly accepting fresh facts of harmony. First perfect consonances, then imperfect, and then suspended discords, which amounted to the delaying of one note in passing from one concord to another; then modifications of the scales were made by the use of accidentals, and approaches were by that means made towards a scale which should admit of much more complex harmonic combinations. But before it could be further modified, it was necessary that a new standpoint should be gained. The great musicians of the 16th century had carried the art to as high a pitch of perfection in the pure polyphonic style as seems to us possible, and men being accustomed to hear in their works the chords which were the result of their polyphony were ready for the first steps of transition from that style to the harmonic. Palestrina, the hero of the old order, died in 1592, and in 1600 the first modern opera, the 'Euridice' of Giacomo Peri, was performed at Florence. It is impossible to point definitely to any particular time and say 'Here the old order ended and the new began,' for in point of fact the periods overlap one another. A species of theatrical performance accompanied by music had been attempted long before this, and secular music had long displayed very free use of chromaticisms similar to the modern style of writing; and, on the other hand, fine examples of polyphony may be found later; but nevertheless the appearance of this opera is a very good typical landmark, since features of the modern school are so clearly displayed in it, such as arias and recitatives accompanied harmonically after the modern manner; moreover in these the harmonies are indicated by figures, which is a matter of considerable importance, as it implies a total change of position relative to the construction of the music. As long as harmony was the accidental result of the combination of different melodies, the idea of using abbreviations for a factor which was hardly a recognized part of the effect would not have occurred to any one, but as soon as harmony came to be recognized as a prominent fact, the use of signs to indicate the grouping of notes into these chords would naturally suggest itself, especially as in the infancy of these views the chords were of a simple description. That the system of figuring a bass was afterwards largely employed in works founded exclusively on the old theory of counterpoint is no argument against this view, as no one can fail to see how entirely inadequate the figuring is to supply any idea whatever of the effects of contrapuntal music. With Peri are associated the names of Cavaliere, Viadana, Caccini, and Monteverde. To Caccini the invention of recitative is attributed, to Viadana that of the 'basso continuo,' and to Monteverde the boldest new experiments in harmony; and to the present question the last of these is the most important. It has already been remarked that during the previous century progress had been rather in technical expression and perfection of detail than in new harmonies. Palestrina's fame does not rest upon elaborate discords, but upon perfect management of a limited number of different combinations. Monteverde evidently abandoned this ideal refinement, and sought for harsher and more violent forms of contrast. Thus in a madrigal 'Straccia me pur,' quoted in Burney's History (iii. 239), the following double suspensions occur:—

But a far more important innovation, which there need be no hesitation in attributing to him, as he was personally blamed for it by the dogmatists of his time, was the use of the minor seventh, which we call the Dominant seventh, without preparation. There is more than one example of this in his works, but one which occurs in a madrigal, 'Cruda Amarilli,' is specially remarkable, as it is preceded by a ninth used evidently as a grace-note in a manner which for his time must have been very daring. It is as follows:—

This independent manner of using the Dominant seventh shows an appreciation of the principle of the relation of chords through a common tonic: that is to say, the connection and relative importance of chords founded on different root notes of a scale according to the modern and not the old ecclesiastical principle. It is true that the very idea of roots of chords did not suggest itself as a realisable conception till nearly a century later; but as is usual in these cases, artistic instinct was feeling its way slowly and surely, and scientific demonstration had nothing to do with the discovery till it came in to explain the results when it was all accomplished. The development of this principle is the most important fact to trace in this period of the history of music. Under the ecclesiastical system one chord was not more important than another, and the very existence of a Dominant seventh according to the modern acceptation of the term was precluded in most scales by the absence of a leading note which would give the indispensable major third. The note immediately below the Tonic was almost invariably sharpened by an accidental in the cadence in spite of the prohibition of Pope John XXII, and musicians were thereby gradually realizing the sense of the dominant harmony; but apart from the cadence this note was extremely variable, and many chords occur, as in the example already quoted from Byrd, which could not occur in that manner in the modern scales, where the Dominant has always a major third. Even considerably later than the period at present under consideration—as in Carissimi and his contemporaries, who represent very distinctly the first definite harmonic period—the habits of the old ecclesiastical style reappear in the use of notes and chords which would not occur in the same tonal relations in modern music; and the effect of confusion which results is all the more remarkable because they had lost the nobility and richness which characterised the last and greatest period of the polyphonic style. The deeply ingrained habits of taking the chords wherever they lay, according to the old teaching of Descant, retarded considerably the recognition of the Dominant and Tonic as the two poles of the harmonic circle of the key; but Monteverde's use of the seventh, above quoted, shows a decided approach to it. Moreover in works of this time the universality of the harmonic Cadence as distinguished from the cadences of the ecclesiastical modes becomes apparent. The ecclesiastical cadences were nominally defined by the progressions of the individual voices, and the fact of their collectively giving the ordinary Dominant Cadence in a large proportion of instances was not the result of principle, but in point of fact an accident. The modern Dominant Harmonic Cadence is the passage of the mass of the harmony of the Dominant into the mass of the Tonic, and defines the key absolutely by giving successively the harmonies which represent the compound tone of the two most important roots in the scale, the most important of all coming last.

The following examples will serve to illustrate the character of the transition. The conclusion of Palestrina's Motet, 'O bone Jesu,' is as follows:—

In this a modern, regarding it in the light of masses of harmony with a fundamental bass, would find difficulty in recognising any particular key which would be essential to a modern Cadence; but the melodic progressions of the voices according with the laws of Cadence in Descant are from that point of view sufficient.

On the other hand, the following conclusion of a Canzona by Frescobaldi, which must have been written within fifty years after the death of Palestrina, fully illustrates the modern idea, marking first the Dominant with great clearness, and passing thence firmly to the chord of the Tonic F:—

It is clear that the recognition of this relation between the Dominant and Tonic harmony was indispensable to the perfect establishment of the modern system. Composers might wake to the appreciation of the effects of various chords and of successions of full chords (as in the first chorus of Carissimi's 'Jonah'), but inasmuch as the Dominant is indispensable for the definition of a key (hence called 'der herrschende Ton'), the principle of modulation, which is the most important secondary feature of modern music, could not be systematically and clearly carried out till that means of defining the transition from one key to another had been attained. Under the old system there was practically no modulation. The impression of change of key is not unfrequently produced, and sustained for some time by the very scarceness of accidentals; since a single accidental, such as F♯ in the progress of a passage in C, is enough to give to a modern musician the impression of change to G, and the number of chords which are common to G and C would sustain the illusion. Sufficient examples have already been given to show that these impressions are illusory, and re erence may be made further to the commencement of Palestrina's 'Stabat Mater' in 8 parts, and his Motet 'Hodie Christus natus est,' and Gibbons's Madrigal 'Ah, dear heart,' which will also further show that even the use of accidentals was not the fruit of any idea of modulation. The frequent use of the perfect Dominant Cadence or 'full Close,' must have tended to accustom composers to this important point in modern harmony, and it is inevitable that musicians of such delicate artistic sensibility as the great composers of the latter part of the 16th century should have approached nearer and nearer to a definite feeling for tonality, otherwise it would be impossible to account for the strides which had been made in that direction by the time of Carissimi. For in his works the principle of tonality, or in other words the fact that a piece of music can be written in a certain key and can pass from that to others and back, is certainly displayed, though the succession of these keys is to modern ideas irregular and their individuality is not well sustained, owing partly no doubt to the lingering sense of a possible minor third to the Dominant.

The supporters of the new kind of music as opposed to the old polyphonic style had a great number of representative composers at this time, as may be seen from the examples in the fourth volume of Burney's History; and among them a revolutionary spirit was evidently powerful, which makes them more important as innovators than as great musicians. The discovery of harmony seems to have acted in their music for a time unfavourably to its quality, which is immensely inferior to that of the works of the polyphonic school they were supplanting. Their harmonic successions are poor, and often disagreeable, and in a large number of cases purely tentative. The tendency was for some time in favour of the development of tunes, to which the new conceptions of harmony supplied a fresh interest. Tunes in the first instance had been homophonic—that is, absolutely devoid of any sense of relation to harmony; and the discovery that a new and varied character could be given to melody by supplying a harmonic basis naturally gave impetus to its cultivation. This also was unfavourable to the development of a high order of art, and it was only by the re-establishment of polyphony upon the basis of harmony, as we see it displayed to perfection in the works of Bach, that the art could regain a lofty standard comparable to that of Palestrina, Lasso, Byrd, Gibbons, and the many great representatives of the art at the end of the sixteenth and the beginning of the seventeenth centuries. In point of fact harmonic music cannot be considered apart from the parts or voices of which it is composed. It consists of an alternation of discord and concord, and the passage of one to the other cannot be conceived except through the progression of the parts. An has been pointed out with respect to the discovery of harmonic or tonal form in musical composition in the article Form, the effect of the new discovery was at first to make composers lose sight of the important element of progression of parts, and to look upon harmony as pre-eminent; consequently the progressions of parts in the works of the middle of the 17th century seem to be dull and uninteresting. Many composers still went on working in the light of the old system, but they must be regarded in relation to that system, and not as representatives of the new; it was only when men strong enough to combine the principles of both schools appeared that modern music sprang into full vigour. The way was prepared for the two great masters who were to achieve this at the beginning of the eighteenth century by the constant labours and experiments of the composers of the seventeenth. It would be impossible to trace the appearance of fresh harmonic material, as the composers were so numerous, and many of their works, especially in the early period, are either lost or unattainable. But in surveying the general aspect of the works which are available, a gradual advance is to be remarked in all departments, and from the mass of experiments certain facts are established. Thus clearness of modulation is early arrived at in occasional instances; for example, in an opera called 'Orontea' by Cesti, which was performed at Venice as early as 1649, there is a sort of short Aria, quoted by Burney (iv. 67), which is as clearly defined in this respect as any work of the present day would be. It commences in E minor, and modulates in a perfectly natural and modern way to the relative major G, and makes a full close in that key. From thence it proceeds to A minor, the subdominant of the original key, and makes another full close, and then, just touching G on the way, it passes back to E minor, and closes fully in that key. This is all so clear and regular according to modern ideas that it is difficult to realise that Cesti wrote within half a century of Palestrina, and of the first recognition of the elements of modern harmony by Caccini, Monteverde, and their fellows. The clearness of each individual modulation, and the way in which the different keys are rendered distinct from one another, both by the use of appropriate Dominant harmony, and by avoiding the obscurity which results from the introduction of foreign chords, is important to note, as it indicates so strongly the feeling for tonality which by constant attention and cultivation culminated in the definite principles which we now use. That the instance was tentative, and that Cesti was guided by feeling and not rule, is sufficiently proved by the fact that not only contemporary musicians, but successive generations up to the end of the century, and even later, frequently fell into the old habits, presenting examples of successions of harmony which are obscure and confused in key.

It is not possible to discover precisely when the use of the seventh in the Dominant Cadence came into use. It has been already pointed out that Monteverde hazarded experimentally the use of the Dominant seventh without preparation, but nevertheless it does not seem to have been used with any obvious frequency by musicians in the early part of the 17th century; but by the middle and latter part it is found almost as a matter of course, as in the works of the distinguished French instrumental composers Dumont, Jacques de Chambonnieres, and Couperin. The following is an example from the second of these—

which shows how easily it might have been introduced in the first instance as a passing note between the root of the first chord and the third of the next, and its true significance have been seen afterwards.

This use of the seventh in the Dominant chord in the Cadence makes the whole effect of the Cadence softer and less vigorous, but for the purpose of defining the key it makes the Cadence as strong as possible; and this, in consideration of the great latitude of modulation and the great richness and variety of harmony in modern music, becomes of great importance. It does this in three ways. First, by simply adding another note to the positive representative notes of the key which are heard in the Cadence, in which in this form the submediant (as A in the key of C) will be the only note of the scale which will not be heard. Secondly, by giving a very complete representation of the compound tone of the root-notes as contained in the Diatonic scale; since the seventh harmonic, though not absolutely exact with the minor seventh which is used in harmony, is so near that they can hardly be distinguished from one another, as is admitted by Helmholtz. And thirdly, by presenting a kind of additional downward-tending leading-note to the third in the Tonic chord, to which it thereby directs the more attention. In relation to which it is also to be noted that the combination of leading note and subdominant is decisive as regards the key, since they cannot occur in combination with the Dominant as an essential Diatonic chord in any other key than that which the Cadence indicates. The softness which characterises this form of the Cadence has led to its avoidance in a noticeable degree in many great works, notwithstanding its defining properties—as in both the first and last movements of Beethoven's C-minor Symphony, the first movement of his Symphony in A, and the Scherzo of the Ninth Symphony. In such cases the definition of key is obtained by other means, as for example in the last movement of the C-minor Symphony by the remarkable reiteration both of the simple concordant cadence and of the Tonic chord. In the first movement of the A Symphony and the Scherzo of the Ninth, the note which represents the seventh, although omitted in the actual harmony of the Cadence, appears elsewhere in the passage preceding. In respect of definition of key it will be apposite here to notice another form of Cadence, namely that commonly called Plagal, in which the chord of the sub-dominant (as F in the key of C) precedes the final Tonic chord. This Cadence is chiefly associated with ecclesiastical music, to which it was more appropriate than it is in more elaborate modern music. On the one hand it avoided the difficulty of the Dominant chord which resulted from the nature of most of the ecclesiastical scales, while its want of capacity for enforcing the key was less observable in relation to the simpler harmonies and absence of modulation of the older style. This deficiency arises from the fact that the chord of the Subdominant already contains the Tonic to which it is finally to pass, and its compound tone which also contains it does not represent a position so completely in the opposite phase to the Tonic as the Dominant does; whence the progression is not strongly characteristic. It also omits the characteristic progression of the leading note up to the Tonic, and does not represent so many positive notes of the scale as the Dominant Cadence. For these various reasons, though not totally banished from modern music, it is rare, and when used appears more as supplementary to the Dominant Cadence, and serving to enforce the Tonic note, than as standing on its own basis. Moreover, as supplementary to the Dominant Cadence it offers the advantage of giving the extra note in the scale which, as has been remarked, is almost inevitably omitted in the Dominant Cadence. Hence an extended type of Cadence is given by some theorists as the most complete, which, as it were, combines the properties of the two Cadences in this form—

In this the sub-dominant chord of the weaker Cadence comes first, and a chord of 6–4, as it is called, is inserted to connect it with the Dominant chord, (as otherwise they would have no notes in common and the connection between them harmonically would not be ostensible,) and then the Dominant chord passes into the Tonic after the usual fashion. Other methods of joining the Subdominant chord to the Dominant chord are plentifully scattered in musical works, as for instance the use of a suspended fourth in the place of the 6–4; but as a type the above answers very well, and it must not be taken as more than a type, since a bare theoretical fact in such a form is not music, but only lifeless theory. As an example of the theory vitalised in a modern form may be given the conclusion of Schumann's Toccata in C for pianoforte (op. 7), as follows:—

In this the weak progression of the 6–4 is happily obviated by connecting the Subdominant and Dominant chords by the minor third of the former becoming the minor ninth of the latter; and at the same time the novelty of using this inversion of the Dominant minor ninth as the penultimate chord, and its having also a slight flavour of the old plagal Cadence, gives an additional vitality and interest to the whole. Composers of the early harmonic period also saw the necessity of putting recognised facts in some form which presented novelty and individuality, and their efforts in that direction will be shortly taken notice of. Meanwhile, it must be observed that the discovery of the harmonic Cadence as a means of taking breath or expressing a conclusion of a phrase and binding it into a definite thought, affected music for a time unfavourably in respect of its continuity and breadth. In Polyphonic times, if it was desirable to make a break in the progress of a movement, the composers had to devise their own means to that end, and consequently a great variety is observable in the devices used for that purpose, which being individual and various have most of the elements of vitality in them. But the harmonic Cadence became everybody's property; and whenever a composer's ideas failed him, or his imagination became feeble, he helped himself out by using the Cadence as a full stop and beginning again; a proceeding which conveys to the mind of a cultivated modern musician a feeling of weakness and inconsequence, which the softness and refinement of style and a certain sense of languor in the works of the early Italian masters rather tend to aggravate. Thus in the first part of Carissimi's Cantata 'Deh contentatevi,' which is only 74 bars in length, there are no less than 10 perfect Dominant Cadences with the chords in their first positions, besides interrupted Cadences and imperfect Cadences such as are sometimes called half-closes. This is no doubt rather an excessive instance, but it serves to illustrate the effect which the discovery of the Cadence had on music; and its effect on English ecclesiastical music of a slightly later period, as for instance in the works of Rogers, will be remembered by musicians acquainted with that branch of the art as a proof that the case is not over-stated. It was no doubt necessary for the development of Form in musical works that this phase should be gone through, and the part it played in that development is considered under that head, and therefore must not be further dwelt upon here. The use of imperfect and interrupted Cadences, as above alluded to, appears in works early in the 17th century, being used relatively to perfect Cadences as commas and semicolons are used in literature in relation to full stops. The form of the imperfect Cadence or half-close is generally a progression towards a pause on the Dominant of the key. The two following examples from Carissimi will illustrate his method of using them,—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 << \relative c'' { \autoBeamOff c8[ d16 e] f8 f c8. d16 d4 } \new Staff { \clef bass aes2 a4 g } \figures { < _ >2 < 6 >4 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/n/lntebc0zi2zqdrc66mcl3b0omre12m7/lntebc0z.png)

in which the key is C, and—

in which the key is E♭. The form of the Interrupted Cadence which is usually quoted as typical is that where the progression which seems to tend through the Dominant chord to the concluding Tonic chord is made to diverge to some other position, such as a chord on the submediant of the key, as on A in the key of C. This form also appears in Carissimi, but not with any apparent definiteness of purpose. In fact, as a predetermined effect the Interrupted Cadence belongs to a more advanced condition of ideas in music than that illustrated by Carissimi and his followers and contemporaries, and only demands a passing notice here from the fact that it does occur, though rarely. Composers in those times were more in the habit of concluding with the Cadence, and repeating part of what they had said before over again with another Cadence; which answers the same requirements of form as most of the uses of Interrupted Cadences by Bach and Handel, but in a much less refined and artistically intelligent manner.

In order to see the bearings of many of the experiments which were made by the early representatives of harmonic music it will be necessary to return for a short space to their predecessors. The basis which the old contrapuntists had worked upon—which we express, for brevity's sake, in the language which is consistently only applicable to harmonic music, as concords and their first inversions and simple discords of suspension—had been varied and enriched by them by the use of passing notes. In the use of these a great deal of ingenuity was exercised, and the devices which resulted were in some instances looked upon as everybody's property, and became quite characteristic of the particular form of art. As a type of these may be taken the following from Dufay, who lived in the 14th century, and has already been spoken of as being quoted by Kiesewetter—

In this the F is clearly taken as a passing note between G and E, and a note on the other side of the E is interpolated before the legitimate passage of the passing note is concluded. This particular figure reappears with astonishing frequency all through the polyphonic period, as in Josquin's Stabat Mater, in Palestrina's Missa Papæ Marcelli, in Gibbons's Hosanna, and in Byrd's Mass. But what is particularly noticeable about it is that it gets so thoroughly fixed as a figure in the minds of musicians that ultimately its true significance is sometimes lost sight of, and it actually appears in a form in which the discord of the seventh made by the passing note is shorn of its resolution. As an example of this (which however is rare) may be taken the following passage from the Credo in Byrd's Mass—

In this the seventh in the treble and its counterpart in the bass never arrive at the B♭ on which they should naturally resolve, and musicians were probably so accustomed to the phrase that they did not notice anything anomalous in the progression. It is probable, moreover, that the device in the first instance was not the result of intellectual calculation—such as we are forced to assume in analysing the progression—but merely of artistic feeling; and in point of fact such artistic feeling, when it is sound, is to all appearances a complex intellectual feat done instinctively at a single stroke; and we estimate its soundness or unsoundness by applying intellectual analysis to the result. The first example given above stands this test, but the latter, judged by the light of the rules of Descant, does not; hence we must regard it as an arbitrary use of a well-known figure which is justifiable only because it is well-known; and the principle will be found to apply to several peculiar features which presently will be observed as making their appearance in harmonic music. The early harmonists proceeded in a similar direction in their attempt to give richness to the bare outline of the harmonic substructure by the use of grace-notes, appoggiaturas, anticipatory notes and the like, and by certain processes of condensation or prolongation which they devised to vary the monotony of uniform resolution of discords. Of these some seem as arbitrary as the use of the characteristic figure of the polyphonic times just quoted from Byrd, and others were the fruit of that kind of spontaneous generalisation which we recognise as sound. It is chiefly important to the present question to notice the principles which guided or seem to have guided them in that which seems to us sound. As an example of insertion between a discord and its resolution, the following passage from a Canzona by Frescobaldi may be taken—

in which the seventh (a) is not actually resolved till (b); the principle of the device being the same as in the early example quoted above from Dufay. Bach carried this principle to a remarkable pitch, as for instance

from the Fugue in B minor, No. 24 in the 'Wohltemperirte Clavier.'

The simple form of anticipation which appears with so much frequency in Handel's works in the following form—

is found commonly in the works of the Italian composers of the early part of the 17th century. Several other forms also are of frequent occurrence, but it is likely that some of them were not actually rendered as they stand on paper, since it is clear that there were accepted principles of modification by which singers and accompanyists were guided in such things just as they are now in rendering old recitatives in the traditional manner, and had been previously in sharpening the leading note of the ecclesiastical modes. Hence it is difficult to estimate the real value of some of the anticipations as they appear in the works themselves, since the traditions have in many instances been lost. An anticipation relative melodically to the general composition of the tonic chord, which is also characteristic of modern music, occurs even as early as Peri, from whose 'Eurydice' the following example is taken—

This feature has a singular counterpart in the Handelian recitative, e.g.—

The following examples are more characteristic of the 17th century.

is quoted by Burney (iv. 34) from Peri. In Carissimi and Cesti are found characteristic closes of recitative in this manner—

but in this case the actual rendering is particularly doubtful, and the passage was probably modified after the manner in which recitatives are always rendered. A less doubtful instance, in which there is a string of anticipations, is from a fragment quoted also by Burney (iv. 147) from a Cantata by Carissimi as follows:—

The use of combinations which result from the simultaneous occurrence of passing notes, a practice so characteristic of Bach, cannot definitely be traced at this early period. Indeed, it is not certain that the musicians had discovered the principle which is most prolific in these effects—namely, the use of preliminary notes a semitone above or below any note of an essential chord, irrespective of what precedes, and at any position relative to the rhythmic divisions of the music, as—

in which B♮, G♯, and D♭, which seem to constitute an actual chord, are merely the result of the simultaneous occurrence of chromatic preliminary passing notes before the essential notes C, A, and C of the common chord of F major. But there is a combination which is very common in the music of the 17th century, which has all the appearance of being derived from some such principle, and demands notice. It appears in Cesti's 'Orontes' (Burney, iv. 68) as follows:—

and, however preceded, it always amounts to the same idea—namely, that of using an unprepared seventh on the subdominant of the key (major or minor) preceding the Dominant chord of the Cadence. This may be explained as a passing note downwards towards the uppermost note of the succeeding concord on the Dominant, which happens to coincide with the passing note upwards between the third of the tonic chord and the root of the Dominant chord,—as C between B♭ and D in the example; in which case it would be derived from the principle above explained; or on the other hand the passage may be explained on the basis of the old theory of passing notes in a way which is highly illustrative of the methods by which novelty is arrived at in music. Composers were accustomed to the progression in which a chord of 6–4 preceded the Dominant chord, as—

and having the particular melodic progression which results from this well fixed in their minds, they inserted a passing note on the strong beat of the bar in the bass without altering the treble, as in the example quoted above from Cesti, and thereby added considerably to the vigour of the passage. This particular feature seems to have been accepted as a musical fact by composers, and appears constantly, from Monteverde till the end of the century, among French and Italians alike; and it is invested with the more interest because it is found in Lully in an improved form, which again renewed its vitality. It stands as follows in a Sarabande by him—

and this form was adopted by Handel, and will be easily recognised as familiar by those acquainted with his works. Corelli indicates the firm hold which this particular seventh had obtained on the minds of musicians by using it in immediate succession to a Dominant 7th, so that the two intervals succeed each other in the following manner:—

in the Sonata II of the Opera 2nda, published in Rome, 1685. These methods of using passing notes, anticipations, and like devices, are extremely important, as it is on the lines thereby indicated that progress in the harmonic department of music is made. Many of the most prolific sources of variety of these kinds had descended from the contrapuntal school, and of these their immediate successors took chief advantage; at first with moderation, but with ever gradually increasing complexity as more insight was gained into the opportunities they offered. Some devices do not appear till somewhat later in the century, and of this kind were the condensation of the resolution of suspensions, which became very fruitful in variety as music progressed. The old-fashioned suspensions were merely temporary retardations in the progression of the parts which, taken together in their simplicity, constituted a series of concords. Thus the succession—

is evidently only a sophisticated version of the succession of sixths—

and the principle which is applied is analogous to the other devices for sophisticating the simplicity of concords which have been analysed above; and the whole shewing how device is built upon device in the progress of the art. Sometime in the 17th century a composer, whose name is probably lost to posterity, hit upon the happy idea of making the concordant notes move without waiting for the resolution of the discordant note, so that the process—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \clef bass \partial 8 \relative c' << { c8 ~ c[ b] b } \\ { ees, d[ d] g } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/6/f6u3tkxxmv82nyfbma712qxjgd4i9eh/f6u3tkxx.png)

in which there are three steps, is condensed into the following (from Alessandro Scarlatti)—

in which there are only two to gain the same end. This device is very common at the end of the 17th century, as in Corelli, and it immediately bore fresh fruit, as the possibility of new successions of suspensions interlaced with one another became apparent, such as—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \partial 8 << \relative f'' << { f8 ~ f[ e] ~ e[ d] ~ d[ c] ~ c[ b] } \\ { c8 b4 a g f } >>

\new Staff { \clef bass \relative a { a8 g[ c] f,[ b] e,[ a] d,[ g] } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/3/f3xct2k3kqlq2qruinnkivwjyl0l3bh/f3xct2k3.png)

in which each shift of a note which would be considered as part of the implied concord creates a fresh suspension. And by this process a new and important element of effect was obtained, for the ultimate resolution of discord into concord could be constantly postponed although the harmonies changed; whereas under the old system each discord must be resolved into the particular concord to which it belonged, and therefore the periods of suspense caused by the discords were necessarily of short duration. In dealing with discords attempts were occasionally made to vary the recognized modes of their resolutions; for instance, there are early examples of attempts to make the minor seventh resolve upwards satisfactorily, and both Carissimi and Purcell endeavoured to make a seventh go practically without any resolution at all, in this form—

from Purcell's 'Dido and Æneas'—where the resolution is only supplied by the second violins—

and from Carissimi—in which it is not supplied at all, if Burney's transcription (iv. 147) is correct. Another experiment which illustrates a principle, and therefore demands notice, is the following from Purcell's service in B♭, in which the analogue of a pedal in an upper part is used to obtain a new harmonic effect:—

About this time also a chord which is extremely characteristic of modern music makes its appearance, namely, the chord of the diminished seventh. This appears, for example, unprepared in Corelli's Sonata X of the 'Opera Terza,' published in 1689, as follows—

In this and in other instances of his use of it, it occupies so exactly analogous a position to the familiar use of the seventh on the subdominant which has already been commented upon at length, that the inference is almost unavoidable that composers first used the diminished seventh as a modification of that well-known device in a minor key, by sharpening its bass note to make it approach nearer to the dominant, and also to often its quality.

[App. pp.667–8: "The inference suggested on p. 681a has been happily verified by Mr. H. E. Wooldridge, who found the two forms of the seventh on the subdominant in a succession which strongly points to their common origin, in the following passage by Stradella:—

in which the minor seventh, arrived at in the manner usual at that time, is seen at (a); and the modified seventh in which the bass is sharpened so as to produce a diminished seventh appears at (b)."]

It will be necessary at this point to turn gain for a short space to theorists, for it was in relation to the standard of harmony which characterises the end of the 17th century that Bameau's attempt was made to put the theory of music on some sort of philosophical basis. He called attention to the fact that a tone consists not only of the single note which everybody recognizes, which he calls the principal sound, but also of harmonic sounds corresponding to notes which stand at certain definite distances from this lower note, among which are the twelfth and seventeenth, corresponding to the fifth and third; that as there is a perfect correspondence between octave and octave these notes can be taken either as the major common chord in its first position, or its inversions; and that judged from this point of view the lower note is the root or fundamental note of the combination. This was the basis of his theory of harmony, and it is generally considered to have been the first explicit statement of the theory of chords in connection with roots or fundamental notes. Rameau declines to accept the minor seventh as part of the compound tone of the root, and he does not take his minor third as represented by the 19th 'upper partial,' which is very remote, but justifies the minor chord on the principle that the minor third as well as the root note generates the fifth (as both C and E♭ would generate G), and that this community between them makes them prescribed by nature. D'Alembert took the part of expositor, and also in some slight particulars of modifyer, of Rameau's principles, in his 'Elements de Musique.' It is not the place here to enter into details with respect to the particulars resulting from the theory, which was applied to explain the construction of scale, temperament, and many other subordinate matters, and to discover the proper progressions of roots, and the interconnection between chords. But a passage in D'Alembert's book deserves especial notice as illustrating modern harmonic as distinguished from the old contrapuntal ideas with respect to the nature of discords; since it shows how completely the old idea of suspensions as retardations of the parts had been lost sight of: 'En general la dissonance étant un ouvrage de l'art, surtout dans les accords qui ne sont point de dominant, tonique, ou de sous-dominant; le seul moyen d'empêcher qu'elle ne déplaise en paroissant trop etrangère à l'accord, c'est qu'elle soit, pour ainsi dire, annoncée a l'oreille en se trouvant dans l'accord précédent, et qu'elle serve par là a lier les deux accords.' The sole exception is in respect of the dominant seventh, which, apparently as a mere matter of experience, does not seem to require this preparatory announcement. Tartini published his theories about the same time as Rameau, and derived the effect of chords from the combinational tones, of which he is reputed to have been the discoverer. Helmholtz has lately shewn that neither theory is complete without the other, and that together they are not complete without the theory of beats, which really affords the distinction between consonance and dissonance; and that all of these principles taken together constitute the scientific basis of the facts of harmony. Both Rameau and Tartini were therefore working in the right direction; but for the musical world Rameau's principles were the most valuable, and the idea of systematising chords according to their roots or fundamental basses has been since generally adopted.

By the beginning of the 18th century the practice of grouping the harmonic elements of music or chords according to the keys to which they belong, which is called observing the laws of tonality, was tolerably universal. Composers had for the most part moved sufficiently far away from the influence of the old ecclesiastical system to be able to realise the first principles of the new secular school. These principles are essential to instrumental music, and it is chiefly in relation to that large department of the modern art that they must be considered. Under the conditions of modern harmony the harmonic basis of any passage is not intellectually appreciable unless the principle of the relations of the chords composing it to one another through a common tonic be observed. Thus if in the middle of a succession of chords in C a chord appears which cannot be referred to that key, the passage is inconsistent and obscure; but if this chord is followed by others which can with it be referred to a different key, modulation has been effected, and the succession is rendered intelligible by its relation to a fresh tonic in the place of C. The range of chords which were recognized as characteristic of any given key was at first very limited, and it was soon perceived that some notes of the scale served as the bass to a larger number and a more important class of them, the Dominant appearing as the most important, as the generator of the larger number of diatonic chords; and since it also contains in its compound tone the notes which are most remote from the chord of the tonic, the artistic sense of musicians led them to regard the Dominant and the Tonic as the opposite poles of the harmonic circle of the key, and no progression was sufficiently definable to stand in a position of tonal importance in a movement unless the two poles were somehow indicated. That is to say, if a movement is to be cast upon certain prominent successions of keys to which other keys are to be subsidiary, those which are to stand prominently forward must be defined by some sort of contrast based on the alternation of Tonic and Dominant harmony. It is probably for this reason that the key of the Subdominant is unsatisfactory as a balance or complementary key of a movement, since in progressing to its Dominant to verify the tonality, the mind of an intelligent listener recognises the original Tonic again, and thus the force of the intended contrast is weakened. This, as has been above indicated, is frequently found in works of the early harmonic period, while composers were still searching for the scale which should give them a major Dominant chord, and the effect of such movements is curiously wandering and vague. The use of the Dominant as the complementary key becomes frequent in works of the latter portion of the 17th century, as in Corelli; and early in the next, as in Bach and Handel, it is recognised as a matter of course; in the time of Haydn and Mozart so much strain was put upon it as a centre, that it began to assume the character of a conventionalism and to lose its force. Beethoven consequently began very early to enlarge the range of harmonic bases of the key by the use of chords which properly belonged to other nearly related keys, and on his lines composers have since continued to work. The Tonic and Dominant centres are still apparently inevitable, but they are supplemented by an enlarged range of harmonic roots giving chromatic combinations which are affiliated on the original Tonic through their relations to the more important notes of the scale which that Tonic represents, and can be therefore used without obscuring the tonality. As examples of this may be taken the minor seventh on the tonic, which properly belongs to the nearly allied key of the subdominant; a major concord on the supertonic, with the minor seventh superimposed, which properly belong to the Dominant key; the major chord on the mediant, which properly belongs to the key of the relative minor represented by the chord of the submediant, and so on.

Bach's use of harmony was a perfect adaptation to it of the principles of polyphony. He resumed the principle of making the harmony ostensibly the sum of the independent parts, but with this difference from the old style, that the harmonies really formed the substratum, and that their progressions were as intelligible as the melodies of which they seemed to be the result. From such a principle sprang an immense extension of the range of harmonic combinations. The essential fundamental chords are but few, and must remain so, but the combinations which can be made to represent them on the polyphonic principle are almost infinite. By the use of chromatic passing and preliminary notes, by retardations, and by simple chromatic alterations of the notes of chords according to their melodic significance, combinations are arrived at such as puzzled and do continue to puzzle theorists who regard harmony as so many unchangeable lumps of chords which cannot be admitted in music unless a fundamental bass can be found for them. Thus the chord of the augmented sixth is probably nothing more than the modification of a melodic progression of one or two parts at the point where naturally they would be either a major or minor sixth from one another, the downward tendency of the one and the upward tendency of the other causing them to be respectively flattened and sharpened to make them approach nearer to the notes to which they are moving. In the case of the augmented sixth on the flat second of the key, there is only one note to be altered; and as that note is constantly altered in this fashion in other combinations—namely by substituting the flattened note for the natural diatonic note, as D♭ for D in the key of C, by Carissimi, Bach, Beethoven, Chopin, in all ages of harmonic music—it seems superfluous to consider whether or no it is a chord with a double root as theorists propose, in which one note is the minor ninth of one root, and the other the major third of another. The way in which ideas become fixed by constant recurrence has already (p. 678) been indicated in the case of a figure which was very characteristic of the polyphonic school, and in that of the subdominant seventh with the early harmonists; in like manner modifications, such as the augmented sixth, and the sharp fifth (which is merely the straining upwards of the upper note of a concord in its melodic progression to the next diatonic note), become so familiar by constant recurrence, that they are accepted as facts, or rather as representatives, by association, of the unmodified intervals, and are used to all intents as essential chords; and moreover being so recognised, they are made liable to resolutions and combinations with other notes which would not have been possible while they were in the unaltered condition; which is not really more to be wondered at than the fact that Bach and his contemporaries and immediate predecessors habitually associated tunes originally cast in the old ecclesiastical modes with harmonies which would have been impossible if those modes had not been superseded by the modern system of scales. The inversion of the above-mentioned augmented sixth as a diminished third is remarkable for two reasons. In the first place, because when used with artistic purpose it is one of the most striking chords in modern music, owing to the gradual contraction towards the resolution—as is felt in the employment of it by both Bach and Beethoven to the words 'et sepultus est' in the 'Crucifixus' of their masses in B minor and D respectively; and in the second, because a distinguished modern theorist (whose work is in many respects very valuable) having discovered that the augmented sixth is a double rooted chord, says that it 'should not be inverted, because the upper note, being a secondary harmonic, and capable of belonging only to the secondary root, should not be beneath the lower, which can only belong to the primary root.' It must not be forgotten, however, in considering the opinions of theorists on the origin of chords such as these, that their explanations are not unfrequently given merely for the purpose of classifying the chords, and of expounding the laws of their resolutions for the benefit of composers who might not be able otherwise to employ them correctly.

The actual number of essential chords has remained the same as it was when Monteverde indicated the nature of the Dominant seventh by using it without preparation, unless a single exception be made in favour of the chord of the major ninth and its sister the minor ninth, both of which Helmholtz acknowledges may be taken as representatives of the lower note or root; and it cannot be denied that they are both used with remarkable freedom, both in their preparation and resolution, by the great masters. Haydn, for instance, who is not usually held to be guilty of harmonic extravagance, uses the major ninth on the Dominant thus in his Quartet in G, Op. 76—

and the minor ninth similarly, and with as great freedom, as follows, in a Quartet in F minor (Trautwein, No. 3).

It is not possible to enter here into discussion of particular questions, such as the nature of the chord frequently called the 'Added Sixth,' to which theorists have proposed almost as many roots as the chord has notes; Rameau originally suggesting the Subdominant, German theorists the Supertonic as an inversion of a seventh, Mr. Alfred Day the Dominant, as an inversion of a chord of the eleventh, and Helmholtz returning to the Subdominant again in support of Rameau. Neither is it necessary to enter into particulars on the subject of the diminished seventh, which modern composers have found so useful for purposes of modulation, or into the devices of enharmonic changes, which are so fruitful in novel and beautiful effects, or into the discordance or non-discordance of the fourth. It is necessary for the sake of brevity to restrict ourselves as far as possible to things which illustrate general principles; and of these none are much more remarkable than the complicated use of suspensions and passing notes, which follow from the principles of Bach in polyphony as applied to harmony, and were remarked on above as laying the foundations of all the advance that has been made in Harmony since his time. Suspensions are now taken in any form and position which can in the first place be possibly prepared even by passing notes, or in the second place be possibly resolved even by causing a fresh discord, so long as the ultimate resolution into concord is feasible in an intelligible manner. Thus Wagner's Meistersinger opens with the phrase—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/4 << \relative c'' { <c e, c>2 <g e c>4. g8 << { g2 ~ g8[ e] f } \\ { c2 } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass \relative c { c2. b4 ~ b a a' s8 } } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/g/1/g1avzcbd5loagdnkfsrfnhp9jy4t9dr/g1avzcbd.png)

in which B is a suspended passing note resolving so as to make a fresh discord with the treble, which in reality is resolved into another discord made by the appearance of a chromatic passing note, and does not find its way into an essential concord till three chords further on; but the example is sufficient to show the application of both principles as above expressed. One of the most powerful suspensions in existence is the following from Bach's Organ Toccata in D minor—

Of strongly accented passing notes the following are good examples—

from the Overture to the Messiah; and—

from Brahms's Ballade in D, which is practically the same passing note as that in the example from Handel, but passing in the opposite direction.

A good example of a succession of combinations resulting from the principles above enumerated with regard to the modification of diatonic notes, and the use of chromatic passing notes, occurs in Bach's Cantata, Christ unser Herr' (p. 208)—

In the 2nd scene of the and act of 'Tristan and Isolde' the combination given theoretically above (p. 679a) actually occurs, and two of the preliminary chromatic notes (*) are sustained as a suspension into the next chord—

In the latter part of the last Act of the same work are some extremely remarkable examples of the adaptation of the polyphonic principle to harmony, entailing very close modulations, for which there is not space here.

The principle of persistence was early recognised in the use of what were called Diatonic successions or sequences. They are defined by Prof. Macfarren as 'the repetition of a progression of harmony, upon other notes of the scale, when all the parts proceed by the same degrees in each repetition as in the original progression,' irrespective of augmented or diminished intervals, or doublings of notes which in other cases it is not desirable to double. And this may be expanded into the more general proposition that when a figure has been established, and the principle and manner of its repetition, it may be repeated analogously without any consideration of the resulting circumstances. Thus Beethoven having established the form of his accompaniment—

goes through with it in despite of the consecutive fifths which result—

Again, a single note whose stationary character has been established in harmony of which it actually forms a part, can persist through harmonies which are otherwise alien to it, and irrespective of any degree of dissonance which results. This was early seen in the use of a Pedal, and as that was its earliest form (being the immediate descendant of the Drone bass mentioned at the beginning of the Article) the singular name of an inverted Pedal was applied to it when the persistent note was in the treble, as in an often-quoted instance from the slow movement of the C-minor Symphony of Beethoven, and a fine example in the Fugue which stands as Finale to Brahms's set of Variations on a Theme by Handel, and in the example quoted from Purcell's Service above. Beethoven even makes more than one note persist, as in the first variation on the Diabelli Valse (op. 121)—

Another familiar example of persistence is persistence of direction, as it is a well-known device to make parts which are progressing in opposite directions persist in doing so irrespective of the combinations which result. For the limitations which may be put on these devices reference must be made to the regular text-books, as they are many of them principles of expediency and custom, and many of them depend on laws of melodic progression, the consideration of which it is necessary to leave to its own particular head.

It appears then, finally, that the actual basis of harmonic music is extremely limited, consisting of concords and their inversions, and at best not more than a few minor sevenths and major and minor ninths; and on this basis the art of modern music is constructed by devices and principles which are either intellectually conceived or are the fruit of highly developed musical instinct, which is according to vulgar phrase 'inspired,' and thereby discovers truths at a single leap which the rest of the world recognise as evidently the result of so complex a generalisation that they are unable to imagine how it was done, and therefore apply to it the useful term 'inspiration.' But in every case, if a novelty is sound, it must answer to verification, and the verification is to be obtained only by intellectual analysis, which in fact may not at first be able to cope with it. Finally, everything is admissible which is intellectually verifiable, and what is inadmissible is so relatively only. For instance, in the large majority of cases, the simultaneous occurrence of all the diatonic notes of the scale would be quite inadmissible, but composers have shown how it can be done, and there is no reason why some other composer should not show how all the chromatic notes can be added also; and if the principles by which he arrived at the combination stand the ultimate test of analysis, musicians must bow and acknowledge his right to the combination. The history of harmony is the history of ever-increasing richness of combination, from the use, first, of simple consonances, then of consonances superimposed on one another, which we call common chords, and of a few simple discords simply contrived; then of a system of classification of these concords and discords by key relationship, which enables some of them to be used with greater freedom than formerly; then of the use of combinations which were specially familiar as analogues to essential chords; then of enlargement of the bounds of the keys, so that a greater number and variety of chords could be used in relation to one another, and finally of the recognition of the principle that harmony is the result of combined melodies, through the treatment of the progressions of which the limits of combination become practically co-extensive with the number of notes in the musical system.[ C. H. H. P. ]