A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/L'Homme Armé

L'HOMME ARMÉ, Lome Armé, or Lomme Armé. I. The name of an old French Chanson, the melody of which was adopted, by some of the Great Masters of the 15th and 16th centuries, as the Canto fermo of a certain kind of Mass—called the 'Missa L'Homme armé'—which they embellished with the most learned and elaborate devices their ingenuity could suggest.

The origin of the song has given rise to much speculation. P. Martini calls it a 'Canzone Provenzale.' Burney (who, however, did not know the words) is inclined to believe it identical with the famous 'Cantilena Rolandi,' antiently sung, by an armed Champion, at the head of the French army, when it advanced to battle. Baini confesses his inability to decide the question: but points out, that the only relique of this poetry which remains to us—a fragment preserved in the 'Proportionale Musices' of Tinctor—makes no mention of Roland, and is not written in the Provençal dialect.[1]

'Lome, lome, lome armé.

Et Robinet tu m'as

La mort donnée,

Quand tu t'en vas.'

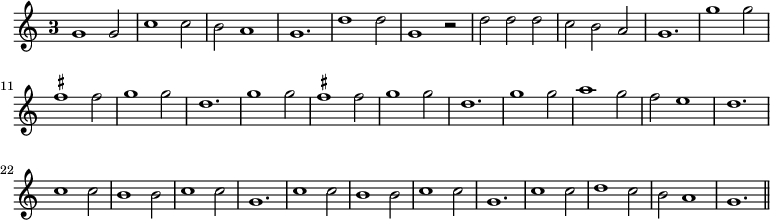

The Melody—an interesting example of the use of the Seventh Mode—usually appears, either in Perfect Time, or the Greater Prolation. Though simple, it lacks neither grace, nor spirit. As might have been predicted, slight differences are observed in the Canti fermi of the various Masses founded upon it; but, they so far correspond, that the reading adopted by Palestrina may be safely accepted as the normal form. We therefore subjoin its several clauses, reduced to modern notation, and transposed into the treble clef.

Upon this unpretending theme, or on fragments of it, Masses were written, by Guglielmo du Fay, Antonio Busnoys, Regis, François Caron, Joannes Tinctor, Philippon di Bruges, La Fage, (or Faugues,) De Orto, Vacqueras, Monsieur mon Compère, at least three anonymous composers who flourished between the years 1484 and 1513, Antonio Brumel, Josquin des Prés, Pierre de la Rue, (Petrus Platensis,) Pipelare, Mathurin Forestyn, Cristofano Morales, Palestrina, and even Carissimi—a host of talented Composers, who all seem to have considered it a point of honour to exceed, as far as in them lay, the fertility of invention displayed by their most learned predecessors, and whose works, therefore, not only embody greater marvels of contrapuntal skill than any other series preserved to us, but also serve as a most useful record of the gradual advancement of Art.

The Masses of Du Fay, and Busnoys, and their successors, Regis, and Caron, are written in the hard and laboured style peculiar to the earlier Polyphonic Schools, with no attempt at expression, but, with an amount of earnest sobriety which was not imitated by some of their followers, who launched into every extravagance that could possibly be substituted for the promptings of natural genius. Josquin, however, while infinitely surpassing his predecessors in ingenuity, brought true genius also into the field; and, in his two Masses on the favourite subject—one for four Voices, and the other for five—has shewn that freedom of style is not altogether inconsistent with science. The Fugues, Canons, Proportions, and other clever devices with which these works are filled, exceed in complexity any thing previously attempted; and many of them are strikingly effective and beautiful—none more so, perhaps, than the third Agnus Dei of the Mass in four parts; a very celebrated movement known as 'Clama ne cesses,' from the 'Inscription' appended to the Superius, (or upper part), for the purpose of indicating that the notes are to be sung continuously, without any rests between them. In this movement, the Superius sings the Canto fermo entirely in Longs and Breves, while the other three Voices are woven together, in Canon, and Close Fugue, with inexhaustible contrivance, and excellent effect. In the second movement of the Sanctus—the 'Pleni sunt'—for three voices, the subject is equally distributed between the several parts, and treated with a melodious freedom more characteristic of the Master than of the age in which he lived. It was printed by Burney in his History, ii. 495.

It might well have been supposed that these triumphs of ingenuity would have terrified the successors of Josquin into silence: but this was by no means the case. Even his contemporaries, Pierre de la Rue, Brumel, Pipelare, and Forestyn, ventured to enter the lists with him; and, at a later period, two very fine Masses, for four and five Voices, were founded on the old Tune by Morales, who laudably made ingenuity give place to euphony, whenever the interest of his composition seemed to demand the sacrifice. It was, however, reserved for Palestrina to prove the possibility, not of sacrificing the one quality for the sake of the other, but of using his immense learning solely as a means of producing the purest and most beautiful effects. His Missa 'L'Homme Armé,' for five voices, first printed in 1570, abounds in such abstruse combinations of Mode, Time, and Prolation, and other rhythmic and constructional complexities, that Zacconi—writing in 1592, two years before the great Composer's death—devotes many pages of his Prattica di Musica to an elaborate analysis of its most difficult 'Proportions,' accompanied by a reprint of the Kyrie, the Christe, the second Kyrie, the first movement of the Gloria, the Osanna, and the Agnus Dei, with minute directions for scoring these, and other movements, from the separate parts. The necessity for some such directions will be understood, when we explain, that, apart from its more easily intelligible complications, the Mass is so constructed that it may be sung either in triple or in common time; and, that the original edition of 1570 is actually printed in the former, and that published at Venice, in 1599, in the latter. Dr. Burney scored all the movements we have mentioned, in accordance with Zacconi's precepts; and his MS. copy (Brit. Mus. Add. MSS. 11,581) bears ample traces of the trouble the process cost him: for Zacconi's reprint is not free from clerical errors, which our learned historian has always carefully corrected. The first Kyrie, in which the opening clause of the Canto fermo is given to the Tenor in notes three times as long as those employed in the other parts, is a conception of infinite beauty, and shows traces of the Composer of the 'Missa Papae Marcelli' in every bar. In the edition of 1570 it stands in triple time; and, in order to make it correspond with that of 1599, it is necessary to transcribe, and re-bar it, placing four minims in a measure, instead of six: when it will be found, not only that the number of bars comes right in the end, but, that every important cadence falls as exactly into the place demanded for it by the rhythm of the piece as it does in the original copy. It is said that Palestrina himself confided this curious secret to one of his disciples, who, five years after his death, superintended the publication of the Venetian edition. If it be asked, why, after having crushed the vain pedants of his day by the 'Missa Papae Marcelli,' the 'Princeps Musicae' should, himself, have condescended to invent conceits as quaint as theirs, we can only state our conviction, that he felt bound, in honour, not only to shew how easily he could beat them with their own weapons, but to compel those very weapons to minister to his own intense religious fervour, and passionate love of artistic beauty. For examples of the music our space compels us to refer the student to Dr. Burney's MS. already mentioned.

The last 'Missa L'Homme Armé' of any importance is that written, for twelve Voices, by Carissimi: this, however, can scarcely be considered as a fair example of the style; for, long before its production, the laws of Counterpoint had ceased to command either the obedience, or the respect, indispensable to success in the Polyphonic Schools of Art.

The original and excessively rare editions of Josquin's two Masses, and that by Pierre de la Rue, are preserved in the Library of the British Museum, together with Zacconi's excerpts from Palestrina, and Dr. Burney's MS. score, which will be found among his 'Musical Extracts.'

None of these works, we believe, have ever been published in a modern form.

II. The title is also attached to another melody, quite distinct from the foregoing—a French Dance Tune, said to date from the 15th century, and printed, with sacred words, by Jan Fruytiers, in his 'Ecclesiasticus,' published, at Antwerp, 1565. The Tune, as there given, is as follows:—

[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ No more information is given by Loquin, 'Melodies populaires,' Paris, 1879.