A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Litany

LITANY (Old Eng. Letanie; Lat. Litaniæ; Gr. Λιτανεία, a Supplication). A solemn form of prayer; sung, by Priests and Choir, in alternate Invocations and Responses; and found in most Office-Books, both of the Eastern and Western Church. [See Litaniæ, etc.]

The origin of the Litany may be traced back to a period of very remote antiquity. Its use was, probably, first instituted in the East: but it was certainly sung, at Vienne, in France, as early as the year 450, if not very much earlier. The English translation—of which alone we propose to treat in the present article—was first published, without musical notes, on the Twenty-seventh of May, 1544—five years before the appearance of King Edward the Sixth's 'First Prayer-Book.' Three weeks later—on the Sixteenth of June—another copy, with the Plain Chaunt annexed, was printed, in London, by Grafton; the Priest's part in black notes, and that for the Choir, in red. It would seem, however, that the congregations of that day were not quite satisfied with unisonous Plain Chaunt: for, before the end of the year, Grafton produced a third copy, set for five voices, 'according to the notes used in the Kynges Chapel.'

This early translation was, in all probability, the work of Archbishop Cranmer, who refers to it in a letter preserved in the State Paper Office. And, as he recommends the notes (or similar ones) to be sung in a certain new Procession which he had prepared by the King's command, there is little doubt that it was he who first adapted the English words to the ancient Plain Chaunt. If this surmise be correct, it supplies a sufficient reason for the otherwise unaccountable omission of the Litany in Marbecke's 'Booke of Common Praier Noted.'

In the year 1560—and, again, in 1565—John Day printed, under the title of 'Certaine notes set forth in foure and three partes, to be song at the Morning Communion, and Evening Prayer,' a volume of Church Music, containing a Litany, for four voices, by Robert Stone, a then gentleman of the Chapel Royal. According to the custom of the time, the Canto fermo is here placed in the Tenor, and enriched with simple, but exceedingly pure and euphonious harmonies, as may be seen in the following example, which will give a fair idea of the whole.

The Rev. J. Jebb has carefully reproduced this interesting composition, in his 'Choral Responses and Litanies'; together with another Litany by Byrd, (given on the authority of a MS. preserved in the Library of Ely Cathedral,) and several others of scarcely inferior merit. The only parts of Byrd's Litany now remaining are, the Cantus, and Bassus: in the following example, therefore, the Altus, and Tenor, (containing the Plain Chaunt,) are restored, in accordance with the obvious intention of the passage, in small notes.

All these Litanies, however, and many others of which only a few fragments now remain to us, were destined soon to give place to the still finer setting by Thomas Tallis. Without entering into the controversy to which this work has given rise, we may assume it as proved, beyond all possibility of doubt, that the words were originally set, by Tallis, in four parts, with the Plain Chaunt in the Tenor. In this form, both the Litany, and Preces, are still extant, in the 'Clifford MS.' (dated 1570), on the authority of which they are inserted in the valuable collection of 'Choral Responses' to which allusion has already been made: and, however much we may be puzzled by the consecutive fifths in the Response, 'And mercifully hear us when we call upon Thee,' and the chord of the in 'We beseech Thee to hear us, Good Lord,' we cannot but believe that the venerable transcription is, on the whole, trustworthy. Tallis's first Invocation, which we subjoin from the 'Clifford MS.,' is, alone, sufficient to show the grandeur of the Composer's conception.

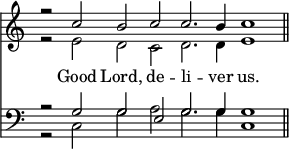

More than one modern writer has condemned the celebrated five-part Litany printed by Dr. Boyce as an impudent corruption of this four-part text. Dean Aldrich goes so far as to assure Dr. Fell, in a letter still extant, that 'Barnard was the first who despoilt it.' The assertion is a rash one. It is too late, now, to ascertain, with any approach to probability, the source whence Barnard's version, printed in 1641, was, in the first instance, derived. There are, in truth, grave difficulties in the way of forming any decided opinion upon the subject. Were the weakness of an unpractised hand anywhere discernible in the counterpoint of the later composition, one might well reject it as an 'arrangement': but it would be absurd to suppose that any Musician capable of deducing the five-part Response, 'Good Lord, deliver us,' from that in four parts, would have condescended to build his work upon another man's foundation.

| From the 4-part Litany. | From the 5-part Litany. |

|

|

The next Response, 'We beseech Thee to hear us, Good Lord,' presents a still more serious crux. The Canto fermo of this differs so widely from any known version of the Plain Chaunt melody that we are compelled to regard the entire Response as an original composition. Now, so far as the Cantus, and Bassus, are concerned, the two Litanies correspond, at this point, exactly: but, setting all prejudices aside, and admitting the third chord in the 'Clifford MS.' to be a manifest lapsus calami, we have no choice but to confess, that, with respect to the mean voices, the advantage lies entirely on the side of the five-part harmony. Surely, the writer of this could—and would—have composed a Treble and Bass for himself!

From the 'Clifford MS.'

From the Five-part Litany.

The difficulties we have pointed out with regard to these two Responses apply, with scarcely diminished force, to all the rest: and, the more closely we investigate the internal evidence afforded by the double text, the more certainly shall we be driven to the only conclusion deducible from it; namely, that Tallis has left us two Litanies, one for four voices, and the other for five, both founded on the same Plain Chaunt, and both harmonised on the same Basses, though developed, in other respects, in accordance with the promptings of two totally distinct ideas.

[ W. S. R. ]