A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Miserere

MISERERE. The Psalm, Miserere mei Deus, as sung in the Sistine Chapel, has excited more admiration, and attained a more lasting celebrity, than any other musical performance on record. Its effect has been described, over and over again, in sober Histories, Guide-books, and Journals without end; but, never very satisfactorily. In truth, it is difficult to convey, in intelligible language, any idea of the profound impression it never fails to produce upon the minds of all who hear it; since it owes its irresistible charm, less to the presence of any easily definable characteristic, than to a combination of circumstances, each of which influences the feelings of the listener in its own peculiar way. Chief among these are, the extraordinary solemnity of the Service into which it is introduced; the richness of its simple harmonies; and, the consummate art with which it is sung: on each of which points a few words of explanation will be necessary.

The Miserere forms part of the Service called Tenebræ; which is sung, late in the afternoon, on three days, only, in the year—the Wednesday in Holy Week, Maundy Thursday, and Good Friday. [See Tenebræ.] The Office is an exceedingly long one: consisting, besides the Miserere itself, of sixteen Psalms and a Canticle from the Old Testament, (sung, with their proper Antiphons, in fourteen divisions); nine Lessons; as many Responsories; and the Canticle, Benedictus Dominus Deus Israel. The whole of this, with the exception of the First Lesson, [see Lamentations], and the Responsories, is sung in unisonous Plain Chaunt: and the sternness of this antient music forms the most striking possible preparation for the plaintive tones which are to follow, while the Ceremonial with which it is accompanied adds immeasurably to the intended effect.

At the beginning of the Service, the Chapel is lighted by six tall Candles, on the Altar; and fifteen others, placed on a large triangular Candlestick, in front. Of these last, one is extinguished at the end of each division of the Psalms. The six Altar-Candles are put out, one by one, during the singing of Benedictus. The only light then remaining is the uppermost one on the triangular Candlestick. This is removed, and carried behind the Altar, where it is completely hidden from view, though not extinguished. The Chapel is, by this time, so dark, that it is only just possible to discern the red Vestments of the Pope, as he kneels at his Genuflexorium, in front of the Altar. Meanwhile, a single Soprano voice sings, with exquisite expression, the Antiphon, 'Christus factus est pro nobis obediens usque ad mortem.' An awful silence follows, during which the Paternoster is said in secret—and the first sad wail of the Miserere then swells, from the softest possible pianissimo, into a bitter cry for mercy, so thrilling in its effect, that Mendelssohn—the last man in the world to give way to unnatural excitement—describes this part of the Service as 'the most sublime moment of the whole.'

There is reason to believe that the idea of adapting the Miserere to music of a more solemn character than that generally used for the Psalms, and thus making it the culminating point of interest in the Service of Tenebræ, originated with Pope Leo X, whose Master of Ceremonies, Paride Grassi, tells us that it was first sung to a Fauxbourdon in 1514. Unhappily, no trace of the music used on that particular occasion can now be discovered. The oldest example we possess was composed, in 1517, by Costanzo Festa, who distributed the words of the Psalm between two Falsi-bordoni, one for four Voices, and the other for five, relieved by alternate Verses of Plain Chaunt—a mode of treatment which has survived to the present day, and upon which no later Composer has attempted to improve. Festa's Miserere is the first of a collection of twelve, contained in two celebrated MS. volumes preserved among the Archives of the Pontifical Chapel. The other contributors to the series were, Luigi Dentice, Francesco Guerrero, Palestrina, Teofilo Gargano, Francesco Anerio, Felice Anerio, an anonymous Composer of very inferior ability, Giovanni Maria Nanini[1], Sante Naldini, Ruggiero Giovanelli, and, lastly, Grogorio Allegri—whose work is the only one of the twelve now remaining in use. So great was the jealousy with which these famous compositions were formerly guarded, that it was all but impossible to obtain a transcript of any one of them. It is said, that, up to the year 1770, only three copies of the Miserere of Allegri were ever lawfully made—one, for the Emperor Leopold I; one, for the King of Portugal; and, a third, for the Padre Martini. Upon the authority of the lastnamed MS. rests that of nearly all the printed editions we now possess. P. Martini lent it to Dr. Burney, who, after comparing it with another transcription given to him by the Cavaliere Santarelli, published it, in 1790, in a work (now exceedingly scarce), called 'La Musica della Settimana Santa,' from which it has been since reproduced, in Novello's 'Music of Holy Week.' The authenticity of this version is undoubted: but it gives only a very faint idea of the real Miserere, the beauty of which depends almost entirely on the manner in which it is sung. A curious proof of this well-known fact is afforded by an anecdote related by Santarelli. When the Choristers of the Imperial Chapel at Vienna attempted to sing from the MS. supplied to the Emperor Leopold, the effect produced was so disappointing, that the Pope's Maestro di Capella was suspected of having purposely sent a spurious copy, in order that the power of rendering the original music might still rest with the Pontifical Choir alone. The Emperor was furious, and despatched a courier to the Vatican, charged with a formal complaint of the insult to which he believed himself to have been subjected. The Maestro di Capella was dismissed from his office: and it was only after long and patient investigation that his explanation was accepted, and he himself again received into favour. There is no reason to doubt the correctness of this story. The circumstance was well known in Rome: and the remembrance of it added greatly to the wonderment produced, nearly a century later, by a feat performed by the little Mozart. On the Fourth Day of Holy Week, 1770, that gifted Boy—then just fourteen years old—wrote down the entire Miserere, after having heard it sung, once only, in the Sistine Chapel. On Good Friday, he put the MS. into his cocked hat, and corrected it, with a pencil, as the Service proceeded. And, not long afterwards, he sang, and played it, with such exact attention to the traditional abellimenti, that Cristoforo, the principal Soprano, who had himself sung it in the Chapel, declared his performance perfect.

Since the time of Mozart, the manner of singing the Miserere has undergone so little radical change, that his copy, were it still in existence, would probably serve as a very useful guide to the present practice. Three settings are now used, alternately—the very beautiful one, by Allegri, already mentioned; a vastly inferior composition, by Tommaso Bai, produced in 1714, and printed both by Burney and Novello; and another, contributed by Giuseppe Baini, in 1821, and still remaining in MS. These are all written in the Second Mode, transposed; and so closely resemble each other in outward form, that, not only is the same method of treatment applied to all, but a Verse of one is frequently interpolated, in performance, between two Verses of another. We shall, therefore, confine our examples to the Miserere of Allegri, which will serve as an exact type of the rest, both with respect to its general style, and to the manner in which the far-famed Abellimenti are interwoven with the phrases of the original melody. These Abellimenti are, in reality, nothing more than exceedingly elaborate four-part Cadenze, introduced in place of the simple closes of the text, for the purpose of adding to the interest of the performance. Mendelssohn paid close attention to one which he heard in 1831, and minutely described it in his well-known letter to Zelter: and, in 1840, Alessandro Geminiani [App. p.719 "(i.e. Alfieri)"] published, at Lugano, a new edition (now long since exhausted) of the music, with examples of all the Abellimenti at that time in use. Most other writers seem to have done their best rather to increase than to dispel the mystery with which the subject is, even to this day, surrounded. Yet, the traditional usage is not so very difficult to understand; and we can scarcely wonder at the effect it produces, when we remember the infinite care with which even the choral portions of the Psalm are annually rehearsed by a picked Choir, every member of which is capable of singing a Solo.

The first Verse is sung, quite plainly, to a Faux-bourdon, for five Voices, exactly as it is printed by Burney, and Novello; beginning pianissimo, swelling out to a thrilling forte, and again taking up the point of imitation sotto voce.

The second Verse is sung, in unisonous Plain Chaunt, to the Second Tone, transposed.

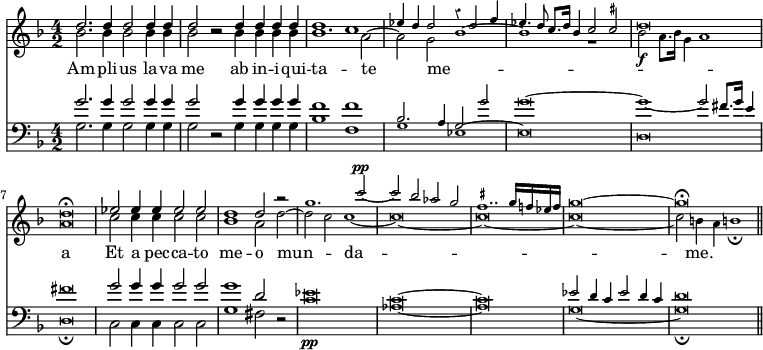

We first meet with the Abellimenti in the third Verse, which is sung in the form of a Concertino—that is to say, by a Choir of four choice Solo Voices. In the following example, the text of the Faux-bourdon is printed in large notes, and the two Abellimenti—one at the end of each clause—in small ones.[2]

In describing this beautiful passage, Mendelssohn says, 'The Abellimenti are certainly not of antient date; but they are composed with infinite talent, and taste, and their effect is admirable. This one, in particular,[3] is often repeated, and makes so deep an impression, that, when it begins, an evident excitement prevades all present.… The Soprano intones the high C, in a pure soft voice, allowing it to vibrate for a time, and slowly gliding down, while the Alto holds its C steadily; so that, at first, I was under the delusion that the high C was still held by the Soprano. The skill, too, with which the harmony is gradually developed, is truly marvellous.'

The unisonous melody of the fourth Verse serves only to bring this striking effect into still bolder relief.

The fifth Verse is sung like the first; the sixth, like the second; the seventh, like the third; and the eighth, like the fourth: and this order is continued—though with endless variations of Tempo, and expression—as far as the concluding Strophe, the latter half of which is adapted to a Double Chorus, written in nine parts, and sung very slowly, with a constant ritardando, 'the singers diminishing or rather extinguishing the harmony to a perfect point.'[4]

[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ Nanini's work is little more than an adaptation of Palertrina's, with an additional Verse for nine Voices.

- ↑ The accidentals in brackets are undoubtedly due to the caprice of individual Singers.

- ↑ That is, the last shewn in our example.

- ↑ These words are Burney's. Adami's direction is, L'ultimo verso del Salmo termina a due Cori, e però sarà la Battuta, Adagio, per fuirlo Piano, smorzando poco a poco l'Armonia.

- ↑ 'Manuel des Ceremonies qui ont lieu pendant la Semaine Sainte.' (Rome, imprimerie de Saint-Michel.)