A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Mordent

MORDENT (Ital. Mordente; Ger. Mordent, also Beisser; Fr. Pincé). One of the most important of the agrémens or graces of instrumental music. It consists of the rapid alternation of a written note with the note immediately below it.

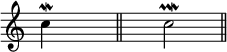

Mordents are of two kinds, the Simple or Short Mordent, indicated by the sign| 1. | Single Mordent. | Double Mordent. |

| Written. |  | |

| Played. | ![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \cadenzaOn c''32[ b' c''8.] \bar "||" c''32[ b' c'' b' c''8] ~ c''4 \bar "||" }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/b/obbkvkm5z0nkxa78xe4lqs183ekrzzi/obbkvkm5.png) | |

The appropriateness of the term Mordent (from mordere, to bite) is found in the suddenness with which the principal note is, as it were, attacked by the dissonant note and immediately released. Walther says its effect is 'like cracking a nut with the teeth,' and the same idea is expressed by the old German term Beisser.

The Mordent may be applied to any note of a chord, as well as to a single note. When this is the case its rendering is as follows—

2. Bach, Sarabande from Suite Française No. 4.

3. Bach, Overture from Partita No. 4.

4. Bach, Organ Fugue in E minor.

5. Air from Suite Française No. 2.

6. Well-tempered Clavier, No. 1, vol. 2.

7. Sarabande from Suite Française No. 5.

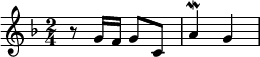

![{ \time 3/4 \key g \major \relative b' { b4.\mordent^\markup { \halign #2 \italic Bar 1. } c8[ a8. g16] | d4 s2 \bar "||" fis4.\mordent^\markup { \italic Bar 5. } g8[ e8. d16] | g4 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/e/7e6ba3lnm68u89uuh1cyia1awh8whu0/7e6ba3ln.png)

![{ \time 3/4 \key g \major \relative b' { b32[ a b8.] s8 c8[ a8. g16] | d4 s2 \bar "||" fes32[ e fes8.] g8[ e8. b16] | g'4 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/f/6/f63y6t3vjym45smby0abpu3zp3f09l1/f63y6t3v.png)

[App. p.719 "Example 4. It should be mentioned that many excellent authorities consider it right to play this passage without the accidental, i.e. using A, not A♯, as the auxiliary note of the mordent. See Spitta's 'Bach,' English edition, i. 403, note 89. Example 7, the last note but one should be D, not B."]

The Long Mordent (pincé double) usually consists of five notes, though if applied to a note of great length it may, according to Emanuel Bach, contain more; it must however never fill up the entire value of the note, as the trill does, but must leave time for a sustained principal note at the end (Ex. 8). Its sign is8. Bach, Sarabande from Partita No. 1.

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 3/4 \key bes \major \relative d'' { << { d8. d16 \afterGrace d4 ~ { d32[ c bes a] } bes16 d f g, | aes8.\prallmordent aes16 aes8 } \\ { <bes f>4 q8 r r4 | <f d>4 q8 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/b/4bttayifegzs9ieqxw41rdockvih3yu/4bttayif.png)

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 3/4 \key bes \major \relative d'' { << { d8. d16 \afterGrace d4 ~ { d32[ c bes a] } bes16 d f g, | aes64 g aes g aes8 aes16 aes8 } \\ { <bes f>4 q8 r r4 | <f d>4 q8 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/6/264b8vcmsex0085kcztj1mo4hlmty3k/264b8vcm.png)

Besides the above, Emanuel Bach gave the name of Mordent to two other graces, now nearly or quite obsolete. One, called the Abbreviated Mordent (pincé etouffé) was rendered by striking the auxiliary note together with its principal, and instantly releasing it (Ex. 9). This grace, which is identical with the Acciaccatura (see the word), was said by Marpurg to be of great service in playing full chords on the organ, but its employment is condemned by the best modern organists. The other kind, called the Slow Mordent, had no distinctive sign, but was introduced in vocal music at the discretion of the singer, usually at the close of the phrase or before a pause (Ex. 10).

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \relative c'' { \cadenzaOn << { c4 } \\ { b32 r r16 r8 } >> \bar "||" c8[ b16 c] g4 r8 g4 \bar "|" c4. b16[ c] c,2\fermata } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/a/m/amymmd1mf95qn13xakb9agmpg7zffhm/amymmd1m.png)

The Pralltriller is characterised by Emanuel Bach as the most agreeable and at the same time the most indispensable of all graces, but also the most difficult. He says that it ought to be made with such extreme rapidity that even when introduced on a very short note, the listener must not be aware of any loss of value.

The proper, and according to some writers the only place for the introduction of the Pralltriller is on the first of two notes which descend diatonically, a position which the Mordent cannot properly occupy. This being the case, there can be no doubt that in such instances as the following, where the Mordent is indicated in a false position, the Pralltriller is in reality intended, and the sign is an error either of the pen or of the press.

12. Mozart, Rondo in D.

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 6/4 \key d \major \relative d''' { d8[( cis]) b\mordent([ a)] g\mordent([ fis)] e\mordent([ d)] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/3/d3z1aus8b0jkvpz7tt545ufe8neodnz/d3z1aus8.png)

Nevertheless, the Mordent is occasionally, though very rarely, met with on a note followed by a note one degree lower, as in the fugue already quoted (Ex. 6). This is however the only instance in Bach's works with which the writer is acquainted.

When the Pralltriller is preceded by an appoggiatura, or a slurred note one degree above the principal note, its entrance is slightly delayed (Ex. 13), and the same is the case if the Mordent is preceded by a note one degree below (Ex. 14).

13. W. F. Bach, Sonata in D.

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 2/2 \key d \major \relative d'' { << { d8*2/3[ a' fis] d' cis b \appoggiatura a4 g2\prall | <g cis,>4 \bar "||" } \\ { r4 fis, e <a cis> | d,2 } \\ { } \\ { r4 d'2 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/f/2f21ibwuw0lkypaulxvz36d2mwmlwop/2f21ibwu.png)

![{ \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 2/2 \key d \major \relative d'' { << { d8*2/3[ a' fis] d' cis b a4 ~ \times 2/3 { a32[ g a } g8.] | <g cis,>4 \bar "||" } \\ { r4 fis, e <a cis> | d,2 } \\ { } \\ { r4 d'2 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/4/l4o783uzeoip124uo5gdrhbpxrji2qd/l4o783uz.png)

14. J. S. Bach, Sarabande from Suite Anglaise No. 3.

![{ \time 3/4 \key g \minor \relative d' { << { d8 f16 e e8 ~ \times 2/3 { e32[ f e } f8.] d8 } \\ { bes4 b2 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/a/y/ays1z1rawqkq24c6hxqdpzlhh301z16/ays1z1ra.png)

Emanuel Bach says that if this occurs before a pause the appoggiatura is to be held very long, and the remaining three notes to be 'snapped up' very quickly, thus—

![{ \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \time 4/4 \partial 2 \relative b' { \cadenzaOn << { b8^\markup { \halign #2 15. \italic Written. } g'4 b,8 | \appoggiatura b4 a2.\prall\fermata r4 \bar "||" b2^\markup { \italic Played. } ~ b32[ a b a] r8 r4\fermata \bar "||" } \\ { g4 cis, | d2. r4 | d2 ~ d8 r r4 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/x/6x71axp5s9r5c1zzzpdqijmgqy81qkq/6x71axp5.png)

Both Mordent and Pralltriller occur very frequently in the works of Bach and his immediate successors; perhaps the most striking instance of the lavish use of both occurs in the first movement of Bach's 'Capriccio on the departure of a beloved brother,' which though only 17 bars in length contains no fewer than 17 Mordents and 30 Pralltrillers. In modern music the Mordent does not occur, but the Pralltriller and Schneller is frequently employed, as for instance by Beethoven in the first movement of the Sonate Pathétique.

Although the Mordent and Pralltriller are in a sense the opposites of each other, some little confusion has of late arisen in the use of both terms and signs. Certain modern writers have even applied the name of Mordent to the ordinary Turn, as for example Czerny, in his Study op. 740, no. 29; and Hummel, in his Pianoforte School, has given both the name and the sign of the Mordent to the Schneller. This may perhaps be accounted for by the supposition that he referred to the Italian mordente, which, according to Dr. Callcott (Grammar of Music), was the opposite of the German Mordent, and was in fact identical with the Schneller. It is nevertheless strange that Hummel should have neglected to give any description of the Mordent proper.[ F. T. ]