A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Noël

NOËL (Old Fr. Nouel; Burgundian Noé; Norman Nud; Poitevin Nau; Germ. Weihnachts Gesang; Eng. Nowell, Nouell, Christmas Carol). A peculiar kind of Hymn, or Canticle, of mediaeval origin, composed, and sung, in honour of the Nativity of Our Lord.

The word Noël has so long been accepted as the French equivalent for 'Christmas,' that we may safely dispense with a dissertation upon its etymology. Moreover, whatever opinions may be entertained as to its root, it is impossible to doubt the propriety of retaining it as the generic name of the Carol: for we continually find it embodied in the Christmas Hymn or Motet, in the form of a joyous [1]exclamation; and it is almost certain that this particular kind of Hymn was first cultivated either in France or Burgundy, and commonly sung there in very antient times.

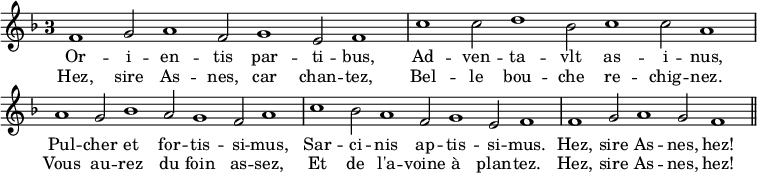

Of the numerous early examples which have fortunately been preserved to us, the most interesting is, undoubtedly, the famous 'Prose de l'âne.' This curious Carol was annually sung, at Beauvais, and Sens, on the Feast of the Circumcision, as early as the 12th century; and formed an important part of the Ceremonial connected with a certain popular Festival called the 'Fête de l'âne,' on which an ass, richly caparisoned, and bearing upon its back a young maiden with a child in her arms, was led through the city, in commemoration of the Flight into Ægypt, and finally brought in solemn procession to the Cathedral, while the crowd chaunted the following quaint, but by no means unmelodious ditty:—

Scarcely less popular in Germany, than the 'Prose de l'âne' in France, were the beautiful Carols 'Resonet in laudibus' (Wir loben all' das Kindelein), and 'Dies est lætitiæ' (Der Tag der ist so freundlich)—the latter, equally well known in Holland as 'Tis een dach van vrolichkeit.' Both these examples are believed to be as old as the 13th century; as is also another—'Tempus adest floridum'—of equally tuneful character. 'In dulci jubilo'—a curious mixture of Latin and Patois, set to a deliciously simple Melody—may possibly be of somewhat later date.

These early forms were succeeded, in the 16th and 17th centuries, by Carols treated, with more or less success, in the Polyphonic style. The credit of having first so treated them is generally given to François Eustache du Caurroy, Maître de Chapelle to Charles IX, Henri III, and Henri IV, on the strength of a collection of pieces, entitled 'Mélanges de la Musique,' published, at Paris, in 1610—the year following his decease. But, Giovanni Maria Nanini, who died, at Rome, in 1607, has left us a magnificent example, in the form of a Motet—'Hodie Christus natus est'—in the course of which he introduces the exclamation, Noé! Noé! with striking effect; and Luca Marenzio published a similar composition, adapted to the same words, as early as 1588. As Du Caurroy's collection was contained in a posthumous volume, it would perhaps be impossible, now, to reconcile the claims of the rival Composers, as to priority of invention; though the French Noëls will, of course, bear no comparison with those written in Italy, in point of excellence. Still, it is only fair to say that the Italian Composers seem to have excited no spirit of emulation among their countrymen; while, for more than a century after the death of Du Caurroy, collections of great value appeared, from time to time, in France: such as Jean François Dandrieu's 'Suite de Noëls,' published early in the 18th century; 'Noei Borguignon de Gui Barôzai,' 1720; 'Traduction des Noels Bourguignons,' 1735; 'Nouveaux Cantiques Spirituels Provençaux,' Avignon, 1750; and many others. We subjoin a few bars of Nanini's Motet, and of one of Du Caurroy's Noëls, as specimens of the distinctive styles of Italy, and France, at the beginning of the 17th century.

G. M. Nanini.

Du Caurroy.

The history of our own English Carols has not yet been exhaustively treated; nor has their Music received the attention it deserves. In no part of the world has the recurrence of Yule-Tide been welcomed with greater rejoicings than in England; and, as a natural consequence, the Christmas Carol has obtained a firm hold, less upon the taste than the inmost affections of the People. Not to love a Carol is to proclaim oneself a churl. Yet, not one of our great Composers seems to have devoted his attention to this subject. We have no English Noëls like those of Eustache du Caurroy. Possibly, the influence of national feeling may have been strong enough, in early times, to exclude the refinements of Art from a Festival the joys of which were supposed to be as freely open to the most unlettered Peasant as to his Sovereign. But, be that as it may, the fact remains, that the old Verses and Melodies have been perpetuated among us, for the most part, by the process of tradition alone, without any artistic adornment whatever; and, unless some attempt be made to preserve them, we can scarcely hope that, in these days of change, they will continue much longer in remembrance. There are, of course, some happy exceptions. We cannot believe that the famous Boar's Head Carol—'Caput apri defero'—will ever be forgotten at Oxford. The fine old melody sung to 'God rest you, merrie Gentlemen,' possessing as it does all the best qualifications of a sterling Hymn Tune, will probably last as long as the Verses with which it is associated. [See Hymn.] But, the beauty of this noble Tune can only be fully appreciated, when it is heard in Polyphonic Harmony, with the Melody placed, according to the invariable custom of the 17th century, in the Tenor. A good collection of English Carols, so treated, would form an invaluable addition to our store of popular Choir Music.

The best, as well as the most popular English Carols, of the present day, are translations from well-known mediæval originals. The Rev. J. M. Neale has been peculiarly happy in his adaptations; among which are the long-established favourites, 'Christ was born on Christmas Day' ('Resonet in laudibus'); 'Good Christian men, rejoice, and sing' ('In dulci jubilo'); 'Royal Day that chasest gloom' ('Dies est lætitiæ'); and 'Good King Wenceslas looked out' ('Tempus adest floridum')—though the Legend of 'Good King Wenceslas' has no connection whatever with the original Latin Verses.[2]

Of Modern Carols, in the strict sense of the word, it is unnecessary to say more than that they follow, for the most part, the type of the ordinary Part Song.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ A modern German critic, F. M. Böhme, mistakes the vowels E.V.O.V.A.E—the mediæval abbreviation for seculorum. Amen—for a similar cry of joy, and is greatly exercised at the admission of a 'Bacchanalian shout' into the Office-Books of the Church! 'Statt Amen der bacchische Freudenruf, evoane!' (Böhme. Das Oratorium; Leipzig, 1861.) [See Appendix, Evovae.]

- ↑ See the Rev. T. Helmore's 'Carols for Christmastide'; a work, which, notwithstanding its modest pretensions, is by far tbe best Collection published in a popular form.