A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Programme-Music

PROGRAMME-MUSIC is an epithet originally intended to apply to that small but interesting class of music which, while unaccompanied by words, seeks to pourtray, or at least suggest to the mind, a certain definite series of objects or events. But the term is also applied, with deplorable vagueness of meaning, to all dramatic, characteristic, or imitative music whatever. It must always remain an open question how far music is able of itself to influence the mind's eye, for the simple reason that some imaginations are vastly more susceptible than others, and can therefore find vivid pictures where others see and hear nothing. Also, in programme-music of all kinds, the imagination is always turned in the required direction by the title of the piece, if by nothing else. It is held by some that music should never seek to convey anything beyond the 'concourse of sweet sounds,' or at least should only pourtray states of feeling. But what is the opinion of the bulk of audiences, who, though artistically ignorant, are not of necessity vulgar-minded? To the uninitiated a symphony is a chaos of sound, relieved by scanty bits of 'tune'; great then is their delight when they can find a reason and a meaning in what is to them like a poem in a foreign tongue. A cuckoo or a thunderstorm assists the mind which is endeavouring to conjure up the required images. And two other facts should be borne in mind: one is that there is a growing tendency amongst critics and educated musicians to invent imaginary 'programmes' where composers have mentioned none as in the case of Weber's Concertstück [App. p.751 "omit the mention of Weber's Concertstück, as that is a specimen of intentional 'Programme-music.' The authority for Weber's intention is handed down by Sir Julius Benedict, in his life of Weber"] and Schubert's C major Symphony, for instance and another, that music, when accompanied by words, can never be too descriptive or dramatic, as in Wagner's music-dramas and the 'Faust' of Berlioz.

May it not at least be conceded that though it is a degradation of art to employ music in imitating the sounds of nature—illustrious examples to the contrary notwithstanding—it is a legitimate function of music to assist the mind, by every means in its power, to conjure up thoughts of a poetic and idealistic kind? If this be granted, programme-music becomes a legitimate branch of art, in fact the noblest, the nature of the programme being the vital point.

The 'Leit-motif' is an ingenious device to overcome the objection that music cannot paint actualities. If a striking phrase once accompany a character or an event in an opera, such a phrase will surely be ever afterwards identified with what it first accompanied. The 'Zamiel motive' in 'Der Freischütz' is a striking and early example of this association of phrase with character. [For a full consideration of this subject see Leit-motif.]

But admirable as this plan may be in opera, where the eye assists the ear, it cannot be said that the attempts of Liszt and Berlioz to apply it to orchestral music have been wholly successful. It is not enough for the composer to label his themes in the score and tell us, as in the 'Dante' Symphony for instance, that a monotone phrase for Brass instruments represents 'All hope abandon, ye who enter here,' or that a melodious phrase typifies Francesca da Rimini. On the other hand, it is quite possible for a musical piece to follow the general course of a poem or story, and, if only by evoking similar states of mind to those induced by considering the story, to form a fitting musical commentary on it. Such programme pieces are Sterndale Bennett's 'Paradise and the Peri' overture, Von Bülow's 'Sänger's Fluch,' and Liszt's 'Mazeppa.' But as the extent to which composers have gone in illustrating their chosen subjects differs widely, as much as the 'Eroica' differs from the 'Battle Symphony,' so it will be well now to review the list of compositions—not a very bulky one before the present century—written with imitative or descriptive intention, and let each case rest on its own merits.

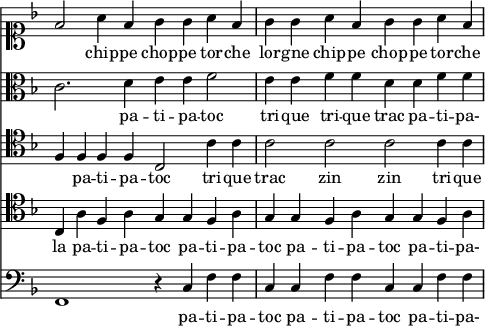

Becker, in his 'Hausmusik in Deutschland' mentions possessing a 16-part vocal canon 'on the approach of Summer,' by a Flemish composer of the end of the 15th century, in which the cuckoo's note is imitated, but given incorrectly. This incorrectness—D C instead of E♭ C—may perhaps be owing to the fact (discussed time ago in the 'Musical Times') that this bird alters her interval as summer goes on.[1] It is but natural that the cuckoo should have afforded the earliest as well as the most frequent subject for musical imitation, as hers is the only bird's note which is reducible to our scale, though attempts have been made, as will be further on, to copy some others. Another canonic part-song, written in 1540 by Lemlin, 'Der Gutzgauch auf dem Zaune sass,' Becker transcribes at length. Here two voices repeat the cuckoo's call alternately throughout the piece. He also quotes a part-song by Antonio Scandelli (Dresden, 1570) in which the cackling of a hen laying an egg is comically imitated thus: 'Ka, ka, ka, ka, ne-ey! Ka, ka, ka, ka, ne-ey!' More interesting than any of these is the 'Dixieme livre des chansons' (Antwerp, 1545) to be found in the British Museum, which contains 'La Bataille à Quatre de Clem. Jannequin' (with a 5th part added by Ph. Verdelot), 'Le chant des oyseaux' by N. Gombert, 'La chasse de lièvre,' anonymous, and another 'Chasse de lièvre' by Gombert. Two at least of these part-songs deserve detailed notice, having been recently performed in Paris. The first has been transcribed in score by Dr. Burney[2] in his 'Musical Extracts' (Add. MS. 11,588), and is a description of the battle of Marignan. Beginning in the usual contrapuntal madrigal style with the words 'Escoutez, tous gentilz Gallois, la victoire du noble roy Françoys,' at the words 'Sonney trompettes et clairons the voices imitate trumpet-calls thus,

and the assault is described by a copious use of onomatopeias such as 'pon, pon, pon,' 'patipatoc,' and 'farirari,' mixed up with exclamations and war-cries. Two bars of quotation will perhaps convey some idea.

This kind of thing goes on with much spirit for a long while, ending at last with cries of 'Victoire au noble roy François! Escampe toutte frelon bigot!' Jannequin is said to have written some other descriptive pieces, in the list of which the 'Chant des oyseaux' of Gombert is wrongly included. [See Jannequin.] [App. p.751 "The sentence on p. 35b, l. 4–7 after musical example, is to be omitted, since both Jannequin and Gombert wrote pieces with the title of 'Le Chant des Oyseaux.' The composition by the former is for four voices, and was published in 1551, that of Gombert being for three voices, and published in 1545."] This latter composition is chiefly interesting for the manner in which the articulation of the nightingale is imitated, the song being thus written down: 'Tar, tar, tar, tar, tar, fria, fria, tu tu tu, qui lara, qui lara, huit huit huit huit, oyti oyti, coqui coqui, la vechi la vechi, ti ti cū ti ti cū titi cū, quiby quiby, tu fouquet tu fouquet, trop coqu trop coqu,' etc. But it is a ludicrous idea to attempt an imitation of a bird by a part-song for Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass [App. p.751 "omit the words 'Soprano, Alto, Tenor and Bass,' since the composition referred to is in three parts, not four. It is 'in four parts' in the sense only of being in four sections, or movements], although some slight effort is made to follow the phrasing of the nightingale's song. The 'Chasse de lièvre' describes a hunt, but is not otherwise remarkable.

The old musicians do not display much originality in their choice of subjects, whether for imitation or otherwise. 'Mr. Bird's Battle' is the title of a piece for virginals contained in a MS. book of W. Byrd's in the Christ Church Library, Oxford. [App. p.751 "refer to Lesson, and Virginal Music, where the exact title is given."] The several movements are headed 'The soldiers' summons—the March of footmen—of horsemen—the Trumpets—the Irish march—the Bagpipe and Drum—etc.' and the piece is apparently unfinished. Mention may also be made of 'La Battaglia' by Francesco di Milano (about 1530) and another battlepiece by an anonymous Flemish composer a little later. Eckhard or Eccard (1589) is said to have described in music the hubbub of the Piazza San Marco at Venice, but details of this achievement are wanting. The beginning of the 17th century gives us an English 'Fantasia on the weather,' by John Mundy, professing to describe 'Faire Wether,' 'Lightning,' 'Thunder,' and 'A faire Day.' This is to be seen in 'Queen Elizabeth's Virginal Book.' The three subjects quoted overleaf alternate frequently, giving thirteen changes of weather, and the piece ends with a few bars expressing 'a cleare day.'

1. Faire wether.

2. Lightning.

3. Thunder.

There is also 'A Harmony for 4 Voices' by Ravenscroft, 'expressing the five usual Recreations of Hunting, Hawking, Dancing, Drinking, and Enamouring': but here it is probable that the words only are descriptive. A madrigal by Leo Leoni (1606) beginning 'Dimmi Clori gentil' contains an imitation of a nightingale. Then the Viennese composer Froberger (d. 1667) is mentioned by several authorities to have had a marvellous power of pourtraying all kinds of incidents and ideas in music, but the sole specimen of his programme-music quoted by Becker—another battle-piece—is a most feeble production. Adam Krieger (1667) gives us a four-part vocal fugue entirely imitative of cats, the subject being as follows—

![<< \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \new Staff { \relative d'' { d2^\( cis4 c | b bes a8\) a[^\( bes b] c4. cis8 d2\) } } \addlyrics { mi __ _ _ _ _ au, mi __ _ _ _ _ au! } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/o/koe1x0mdt7swrxa778wqeejn62bhzom/koe1x0md.png)

Titles now begin to be more impressive, and the attempt of Buxtehude (b. 1637) to describe 'the Nature and Properties of the Planets' in a series of seven Suites for Clavier would be very ambitious had it extended further than the title-page. Kuhnau's 'Biblische Historien' are more noticeable. These were six Organ Sonatas describing various scenes in the sacred narrative. 'David playing before Saul' is one—a good musical subject; 'Jacob's wedding' is more of a programme piece, and contains a 'bridal song' for Rachel. 'Gideon' is of the usual order of battle-pieces, and 'Israel's death' is not very descriptive. Burney gives 'David and Goliath' and 'The ten plagues of Egypt' as the titles of the other two.

Amongst descriptive vocal pieces of this period should be noticed the Frost scene in Purcell's 'King Arthur,' in which the odd effect of shivering and teeth-chattering is rendered by the chorus. Also the following aria from an opera by Alessandro Melani (1660–96):

Talor la granochiella nel pantano

Per allegrezza canta qua qua ré,

Tribbia il grillo tri tri tri,

L'Agnellino fa bé bé,

L'Usignuolo chiu chiu chiu,

Ed il gal curi chi chi.

These imitations are said to have created much delight among the audience. Coming now to the great masters we find singularly few items for our list. J. S. Bach has only one, the 'Capriccio sopra la lontananza del suo fratello diletissimo,' for pianoforte solo, in which occurs an imitation of a posthorn. We cannot include the descriptive choruses which abound in cantatas and oratorios, the catalogue would be endless. We need only mention casually the 'Schlacht bei Hochstädt' of Em. Bach, and dismiss Couperin with the remark that though he frequently gives his harpsichord pieces sentimental and flowery names, these have no more application than the titles bestowed so freely and universally on the 'drawing-room' music of the present day. [App. p.752 "the statement that the titles given by Couperin to his harpsichord pieces have no application in the sense of 'Programme-music,' is to be corrected; to mention but two instances out of many, 'Le Reveil-matin' is as true a specimen of the class as could be found in all music, while 'La Triomphante' exceeds 'The Battle of Prague' as far in graphic delineation as it does in musical beauty."] D. Scarlatti wrote a well-known 'Cat's Fugue.' Handel has not attempted to describe in music without the aid of words—for the 'Harmonious Blacksmith' is a mere after-invention, but he occasionally follows not only the spirit but the letter of his text with a faithfulness somewhat questionable, as in the setting of such phrases as 'the hail ran along upon the ground,' 'we have turned,' and others, where the music literally executes runs and turns. But this too literal following of the words has been even perpetrated by Bach ('Mein Jesu ziehe mich, so will ich laufen.'), and by Beethoven (Mass in D, 'et ascendit in cœlum'); and in the present day the writer has heard more than one organist at church gravely illustrating the words 'The mountains skipped like rams' in his accompaniment, and on the slightest allusion to thunder pressing down three or four of the lowest pedals as a matter of course. Berlioz has ridiculed the idea of interpreting the words 'high' and 'low' literally in music, but the idea is now too firmly rooted to be disturbed. Who would seek to convey ethereal or heavenly ideas other than by high notes or soprano voices, and a notion of 'the great deep' or of gloomy subjects other than by low notes and bass voices?

A number of Haydn's Symphonies are distinguished by names, but none are sufficiently descriptive to be included here. Characteristic music there is in plenty in the 'Seasons,' and 'Creation,' but the only pieces of actual programme-music—and those not striking specimens—are the Earthquake movement, 'Il Terremoto,' in the 'Seven Last Words,' and the 'Representation of Chaos' in the 'Creation,' by an exceedingly unchaotic fugue. Mozart adds nothing to our list, though it should be remembered how greatly he improved dramatic music. We now come to the latter part of the 18th century, when programme pieces are in plenty. It is but natural the numerous battles of that stormy epoch should have been commemorated by the arts, and accordingly we find Battle Sonatas and Symphonies by the dozen. But first a passing mention should be made of the three symphonies of Ditters von Dittersdorf (1789) on subjects from Ovid's Metamorphoses, viz. The four ages of the world; The fall of Phaeton; and Actæon's Metamorphosis into a stag.

In an old volume of pianoforte music in the British Museum Library (g. 138) may be seen the following singular compositions:—

1. 'Britannia, an Allegorical Overture by D. Steibelt, describing the victory over the Dutch Fleet by Admiral Duncan.' In this, as well as all other similar pieces, the composer has kindly supplied printed 'stage directions' throughout. Thus 'Adagio: the stillness of the night. The waves of the sea. Advice from Captain Trollope' (which is thus naïvely depicted):—

'Sailing of the Dutch Fleet announced (by a march!). Beat to arms. Setting the sails, "Britons, strike home." Sailing of the Fleet. Songs of the sailors. Roaring of the sea. Joy on sight of the enemy. Signal to engage. Approach to the enemy. Cannons. Engagement. Discharge of small arms. Falling of the mast (a descending scale passage). Cries of the wounded:—

Heat of the action. Cry of victory. "Rule Britannia," (interrupted by) Distress of the Vanquished. Sailing after victory. Return into port and acclamation of the populace. "God save the King."' This composer has also written a well-known descriptive rondo, 'The Storm,' as well as other programme pieces, the titles of which will be found under Pianoforte Music [vol. ii. 725b].

2. 'The Royal Embarkation at Greenwich, a characteristic Sonata by Theodore Bridault.' This piece professes to describe 'Grand Salutation of Cannon and Music. The barge rowing off to the Yatch. "Rule Britannia." His Majesty going on board. Acclamations of the people' (apparently not very enthusiastic).

![<< \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \new Staff { \relative b' { \repeat unfold 3 { r2 r4 <b f d> | <c g e>1 } } }

\new Staff { \clef bass \relative g { r2 r4 <g d g,>4 | <c g c,>1 | r2 r4 <g d g,> | c32*4/3[ e c] g[ c g] e[ g e] c[ e c] g[ c g] e[ g e] c4 | r2 r4 <g' d' g> | <c g' c>1 \bar "||" } } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/k/hk5th6glwfqbgp3mrkpkc4mnoqbki0y/hk5th6gl.png)

3. 'The Battle of Egypt, by Dr. Domenico Briscoli.' This is a piece of the same kind, with full descriptions, and ending, as usual, with 'God save the King.'

4. The Landing of the Brave 42nd in Egypt. Military Rondo for Pianoforte, by T. H. Butler.' The programme is thus stated: 'Braving all opposition they land near Fort Aboukir, pursue the French up the sand-hills, and in a bloody battle conquer Buonaparte's best troops.'

5. Another 'Admiral Duncan's Victory,' by J. Dale.

6. 'Nelson and the Navy, a Sonata in commemoration of the glorious 1st of August, 1798, by J. Dale.' A similar sea-piece, in which the blowing up of L'Orient is represented by a grand ascending scale passage.

7. A third 'Admiral Duncan,' by Dussek.

8. 'The Sufferings of the Queen of France,' by Dussek. This is a series of very short movements strung together, each bearing a name. A deep mourning line surrounds the title-page. 'The Queen's imprisonment (largo). She reflects on her former greatness (maestoso). They separate her from her children (agitato assai). Farewell. They pronounce the sentence of death (allegro con furia). Her resignation to her fate (adagio innocente). The situation and reflections the night before her execution (andante agitato). The guards come to conduct her to the place of execution. They enter the prison door. Funeral March. The savage tumult of the rabble. The Queen's invocation to the Almighty just before her death (devotamente). The guillotine drops (a glissando descending scale). The Apotheosis.'

9. 'A complete delineation of the Procession … in the Ceremony of Thanksgiving, 1797,' by Dussek. The full title nearly fills a page. Here we have horses prancing and guns firing, and the whole concludes with Handel's Coronation Anthem.

10. 'A Description in Music of Anacreon's L'Amour piqué par une abeille,' by J. Mugnié. This is perhaps the first attempt to illustrate a poem, and as such is commendable.

11. 'The Chace, or Royal Windsor Hunt,' by H. B. Schroeder; a descriptive hunting-piece.

12. 13. 'The Siege of Valenciennes,' and 'Nelson's Victory,' anonymous.

Far more famous, though not a whit superior to any of these, was Kotzwara's 'Battle of Prague.' It seems to be a mere accident that we have not a piece of the same kind by Beethoven on the Battle of Copenhagen![3] There is also a 'Conquest of Belgrade,' by Schroetter; and a composition by Bierey, in which one voice is accompanied by four others imitating frogs—'quaqua!'—belongs also to this period. Mr. Julian Marshall possesses a number of compositions of an obscure but original-minded composer of this time (though perhaps a Prince), Signor Sampieri. He appears to have been a pianoforte teacher who sought to make his compositions interesting to his pupils by means of programmes, and even by illustrations placed among the notes. One of his pieces is 'A Grand Series of Musical Compositions expressing Various Motions of the Sea.' Here we have 'Promenade, Calm, Storm, Distress of the Passengers, Vessel nearly lost,' etc. Another is modestly entitled 'A Novel, Sublime, and Celestial, Piece of Music called Night; Divided into 5 Parts, viz. Evening, Midnight, Aurora, Daylight, and The Rising of the Sun.' On the cover is given 'A short Account how this Piece is to be played. As it is supposed the Day is more Chearful than the Night, in consequence of which, the Evening, begins by a piece of Serious Music.—Midnight, by simple and innocent, at the same time shewing the Horror & Dead of the Night. Aurora, by a Mild encreasing swelling or crescendo Music, to shew the gradual approach of the Day. Daylight, by a Gay & pleasing Movement, the Rising of the Sun, concludes by an animating & lively Rondo, & as the Sun advance into the Centre of the Globe, the more the Music is animating, and finishes the Piece.'

In this composition occur some imitations of birds. That of the Thrush is not bad:

The Blackbird and the Goldfinch are less happily copied. Other works of this composer bear the titles of 'The Elysian Fields,' 'The Progress of Nature in various departments,' 'New Grand Pastorale and Rondo with imitation of the bagpipes'; and there is a curiously illustrated piece descriptive of a Country Fair, and all the amusements therein.

Coming now to Beethoven, we have his own authority for the fact, that when composing he had always a picture in his mind, to which he worked.[4] But in two instances only has he described at all in detail what the picture was. These two works, the Pastoral and the Battle Symphonies, are of vastly different calibre. The former, without in the slightest degree departing from orthodox form, is a splendid precedent for programme-music. In this, as in most works of the higher kind of programme-music, the composer seeks less to imitate the actual sounds of nature than to evoke the same feelings as are caused by the contemplation of a fair landscape, etc. And with such consummate skill is this intention wrought out that few people will be found to agree with a writer in the 'Encyclopædia Britannica ' (former edition) who declares that if this symphony were played to one ignorant of the composer's intention the hearer would not be able to find out the programme for himself. But even were this the case—as it undoubtedly is with many other pieces—it would be no argument against programme-music, which never professes to propound conundrums. It may be worth mentioning that the Pastoral Symphony has actually been 'illustrated' by scenes, ballet and pantomime action in theatres. This was done at a festival of the Künstler Liedertafel of Düsseldorf in 1863 'by a series of living and moving tableaux in which the situations described by the Tone-poem are scenically and pantomimically illustrated.'[5] A similar entertainment was given by Howard Glover in London the same and following year.

Another interesting fact concerning the Pastoral Symphony is the identity of its programme with that of the 'Portrait Musical de la Nature' of Knecht, described below. The similarity however does not extend to the music, in which there is not a trace of resemblance. Mention has elsewhere been made of an anticipation of the Storm music in the 'Prometheus' ballet music, which is interesting to note. Some description of the little-known 'Battle Symphony' may not be out of place here. It is in two parts; the first begins with 'English drums and trumpets' followed by 'Rule Britannia,' then come 'French drums and trumpets' followed by 'Malbrook.' More trumpets to give the signal for the assault on either side, and the battle is represented by an Allegro movement of an impetuous character. Cannon of course are imitated—Storming March—Presto—and the tumult increases. Then Malbrook is played slowly and in a minor key, clearly, if somewhat inadequately, depicting the defeat of the French. This ends the 1st part. Part 2 is entitled 'Victory Symphony' and consists of an Allegro con brio followed by 'God save the King'—a melody, it may be remarked, which Beethoven greatly admired. The Allegro is resumed, and then the anthem is worked up in a spirited fugato to conclude.

Of the other works of Beethoven which are considered as programme, or at least characteristic music, a list has been already given at p. 206b of vol. i. It is sufficient here to remark that the 'Eroica' Symphony only strives to produce a general impression of grandeur and heroism, and the 'Pathetic' and 'Farewell' Sonatas do but pourtray states of feeling, ideas which music is peculiarly fitted to convey. The title 'Wuth über den verlorenen Groschen,' etc., given by Beethoven to a Rondo (op. 129) is a mere joke.

Knecht's Symphony here demands a more detailed notice than has yet been given it. The title-page runs as follows—

Le Portrait Musical de la Nature, ou Grande Simphonie … (For ordinary orchestra minus clarinets.) Laquelle va exprimer par le moyen des sons:1. Une belle Contrée ou le Solell luit, les doux Zephirs voltigent, les Buisseaux traversent le vallon, les oiseaux gazouillent, un torrent tombe du haut en murmurant, le berger siffle, les moutons sautent, et la bergere fait entendre sa douce voix.

2. Le ciel commence a deveuir soudain et sombre, tout le voisinage a de la peine de respirer et s'effraye, les nuages noirs montent, les vents se mettent à faire un bruit, le tonnerre gronde do loin et l'orage approche à pas lents.

3. L'orage accompagné des vents murmurans et des plules battans gronde avec toute la force, les sommets des arbres font un murm, et le torrent roule ses eaux avec un bruit épouvantable.

4. L'orage s'appaise peu à peu les nuages se dissipent et le clel devient clair.

5. La Nature transportée de la joie éléve sa voix vers le ciel et rend au créateur les plus vives graces par des chants doux et agréables.

Dediée à Monsieur l'Abbé Vogler Premier Maître de Chapelle Electorate de Palatin-Bavar, par Justin Henri Knecht.

[See Knecht, vol. ii. p. 66.]

In spite of these elaborate promises the symphony, regarded as descriptive music, is a sadly weak affair; its sole merit lying in the originality of its form. In the first movement (G major, Allegretto) instead of the 'working out' section there is an episode, Andante pastorale, D major (a), formed from the first subject (b) by metamorphosis, thus—

![{ \time 3/8 \key d \major \relative d'' << { d4^"(a)" a8 | fis'4 d8 | a' g e | d[ cis] } \\ { d,8 d16 a fis'8 | d d16 a fis'8 | e e16 a, g'8 | a,4 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/9/r/9rayspthek5x42uibop3lsxz32fro7m/9rayspth.png)

The Abbé Vogler, to whom this composition is dedicated, was himself a great writer of programme-music, having described in his Organ Concertos such elaborate scenes as the drowning of the Duke Leopold in a storm, the Last Judgement, with graves opening, appearance of the mystic horsemen and choruses of damned and blessed—and a naval battle in the fashion of Dussek and the rest.

Coming now to modern times, we find a perfect mania for giving names to pieces—showing the bias of popular taste. Every concert overture must have a title, whether it be programme-music or not. Every 'drawing-room' piece, every waltz or galop, must have its distinctive name, till we cease to look for much descriptiveness in any music. It cannot be said that all Mendelssohn's overtures are programme-music. The Midsummer Night's Dream, with its tripping elves and braying donkey, certainly is, but the 'Meeresstille,' 'Hebrides,' and 'Melusine' are only pieces which assume a definite colour or character, the same as his 'Italian' and 'Scotch' symphonies. To this perfectly legitimate extent many modern pieces go; and some term like 'tinted music' should be invented for this large class of compositions, which includes the greater part of Schumann's pianoforte works, for instance. The 'Carneval' is decidedly programme-music, so are most of the 'Kinderscenen' and 'Waldscenen'; while others, despite their sometimes extravagant titles, are purely abstract music: for it is well known that Schumann often invented the titles after the pieces were written. Such pieces as the 'Fantasia in C' and the longer 'Novelletten,' from their poetic cast and free form give a decided impression of being intended for descriptive music.

Spohr's Symphony 'Die Weihe der Töne' (The Consecration of Sound) bears some relation to the Pastoral Symphony in its first movement; the imitations of Nature's sounds are perhaps somewhat too realistic for a true work of art, but have certainly conduced to its popularity. For no faults are too grave to be forgiven when a work has true beauty. His 'Seasons' and 'Historical' Symphonies are less characteristic.

Felicien David's wonderful ode-symphonie 'Le Desert' must not be omitted, though it is almost a cantata, like the 'Faust' of Berlioz. Modern dramatic music, in which descriptiveness is carried to an extent that the old masters never dreamed of, forms a class to itself. This is not the place to do more than glance at the wonderful achievements of Weber and Wagner.

Berlioz was one of the greatest champions of programme-music; he wrote nothing that was not directly or indirectly connected with poetical words or ideas; but his love of the weird and terrible has had a lamentable effect in repelling public admiration for such works as the 'Francs Juges' and 'King Lear' overtures. Music which seeks to inspire awe and terror rather than delight can never be popular. This remark applies also to much of Liszt's music. The novelty in construction of the 'Symphonische Dichtungen' would be freely forgiven were simple beauty the result. But such subjects as 'Prometheus' and 'The Battle of the Huns,' when illustrated in a sternly realistic manner, are too repulsive, the latter of these compositions having indeed lately called forth the severe remark from an eminent critic that 'These composers (Liszt etc.) prowl about Golgotha for bones, and, when found, they rattle them together and call the noise music.' But no one can be insensible to the charms of the preludes 'Tasso,' 'Dante,' and 'Faust,' or of some unpretentious pianoforte pieces, such as 'St. François d'Assise prédicant aux oiseaux,' 'Au bord d'une source,' 'Waldesrauschen,' and others.

Sterndale Bennett's charming 'Paradise and the Peri' overture is a good specimen of a work whose intrinsic beauty pulls it through. An unmusical story, illustrated too literally by the music,—yet the result is delightful. Raff, who ought to know public taste as well as any man, has named seven out of his nine symphonies, but they are descriptive in a very unequal degree. The 'Lenore' follows the course of Bürger's well-known ballad, and the 'Im Walde' depicts four scenes of forest life. Others bear the titles of 'The Alps,' 'Spring,' 'Summer,' etc., but are character-music only. Raff, unlike Liszt, remains faithful to classical form in his symphonies, though this brings him into difficulties in the Finale of the 'Forest' symphony, where the shades of evening have to fall and the 'Wild Hunt' to pass, twice over. The same difficulty is felt in Bennett's Overture.

That the taste for 'music that means something' is an increasing, and therefore a sound one, no one can doubt who looks on the enormous mass of modern music which comes under that head. Letting alone the music which is only intended for the uneducated, the extravagant programme quadrilles of Jullien, and the clever, if vulgar, imitative choruses of Offenbach and his followers, it is certain that every piece of music now derives additional interest from the mere fact of having a distinctive title. Two excellent specimens of the grotesque without vulgarity in modern programme-music are Gounod's 'Funeral March of a Marionette' and Saint-Saëns' 'Danse Macabre.' In neither of these is the mark overstepped. More dignified and poetic are the other 'Poèmes Symphoniques' of the latter composer, the 'Rouet d'Omphale' being a perfect gem in its way. We may include Goldmark's 'Landliche Hochzeit' symphony in our list, and if the Characteristic Studies of Moscheles, Liszt, Henselt and others are omitted, it is because they belong rather to the other large class of character-pieces.

It will be noticed, on regarding this catalogue, how much too extended is the application of the term 'programme-music' in the present day. If every piece which has a distinct character is to be accounted programme-music, then the 'Eroica' Symphony goes side by side with Jullien's 'British Army Quadrille,' Berlioz's 'Episode de la vie d'un Artiste' with Dussek's 'Sufferings of the Queen of France,' or Beethoven's 'Turkish March' with his 'Lebewohl' sonata. It is absurd, therefore, to argue for or against programme-music in general, when it contains as many and diverse classes as does abstract music. As before stated, theorising is useless—the result is everything. A beautiful piece of music defies the critics, and all the really beautiful pieces in the present list survive, independently of the question whether programme-music is a legitimate form of art or not.[ F. C. ]

- ↑ Spohr, in his Autobiography, has quoted a cuckoo in Switzerland which gave the intermediate note—G. F, E.

- ↑ Reprinted in the Prince de la Moskowa's collection.

- ↑ See his letters to Thomson, in Thayer, iii. 448, 9. He asked 50 gold ducats for the job.

- ↑ In a conversation with Neate, in the fields near Baden (Thayer, iii. 343). 'Ich habe immer ein Gemälde in meinen Gedanken, wenn ich am componiren bin, und arbeite nach demselben.'

- ↑ See 'Beethoven im Malkasten' by Jahn, 'Gesam. Aufsäzte.'