A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Rule, Britannia!

RULE, BRITANNIA! The music of this noble 'ode in honour of Great Britain,' which, according to Southey, 'will be the political hymn of this country as long as she maintains her political power,' was composed by Arne for his masque of 'Alfred' (the words by Thomson and Mallet), and first performed at Cliefden House, Maidenhead, Aug. 1, 1740. Cliefden was then the residence of Frederick, Prince of Wales, and the occasion was to commemorate the accession of George I, and the birthday of Princess Augusta. The masque was repeated on the following night, and published by Millar, Aug. 19, 1740.

Dr. Arne afterwards altered the masque into an opera, and it was so performed at Drury Lane Theatre on March 20, 1745, for the benefit of Mrs. Arne. In the advertisements of that performance, and of another in April, Dr. Arne entitles 'Rule, Britannia!' 'a celebrated ode,' from which it may be inferred that it had been especially successful at Cliefden, and had made its way, though the masque itself had not been performed in public. Some detached pieces had been sung in Dublin, but no record of a public performance in England has been discovered.

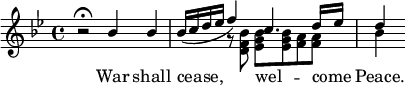

The year 1745, in which the opera was produced, is memorable for the Jacobite rebellion in the North, and in 1746 Handel produced his 'Occasional Oratorio,' in which he refers to its suppression, 'War shall cease, welcome Peace,' adapting those words to the opening bars of 'Rule, Britannia!'—in itself a great proof of the popularity of the air.

By a singular anachronism, Mr. Schœlcher, in his 'Life of Handel' (p. 299), accuses Arne of copying these and other bars in the song from Handel, instead of Handel's quoting them from Arne. He says also: 'Dr. Arne's Alfred, which was an utter failure, appears to have belonged to 1751.' It was not Arne's 'Alfred' that failed in 1751, but Mallet's alteration of the original poem, which he made shortly after the death of Thomson. Mallet endeavoured to appropriate the credit of the masque, as he had before appropriated the ballad of 'William and Margaret,' and thereby brought himself into notice.[1] Mallet's version of 'Alfred' was produced in 1751, and, in spite of Garrick's acting, failed, as it deserved to fail.[2]

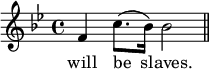

Mr. Schœlcher's primary mistake led him to search further for resemblances between the music of Handel and of Arne. He found

in Handel, and

in Arne. Not knowing that this cadence was the common property of the whole world, he imagined that Arne must have copied it from Handel. His objections have been answered by Mr. Husk, Mr. Roffe, and others in vols. iv. and v. of 'Notes and Queries,' 2nd Series, to which the curious may be referred. Even the late M. Fétis, who had Anglophobia from his youth, and who repaid the taunts of Dr. Burney upon French music with sneers upon English composers, admits that 'Arne eut du moins le mérite d'y mettre un cachet particulier, et de ne point se borner, comme tous les compositeurs Anglais de cette époque, à imiter Purcell ou Hændel.' M. Fétis's sneer at the other English composers of 'cette époque' as copyists of Handel is quite without foundation. Handel's music, even with other words, was published under his name as its recommendation; English church musicians would have thought it heresy to follow any other models than those of their own school, and English melodists could not find what they required in Handel. Ballad operas, Arne's Shakespearian songs, Vauxhall songs, ballads, and Anglo-Scottish songs, were the order of the day 'à cette époque,' and Handel's purse suffered severely from their opposition.

The score of 'Rule, Britannia!' was printed by Arne at the end of 'The Judgment of Paris,' which had also been produced at Cliefden in 1740. The air was adopted by Jacobites as well as Hanoverians, but the former parodied, or changed, the words. Among the Jacobite parodies, Ritson mentions one with the chorus—

Rise, Britannia! Britannia, rise and fight!

Restore your injured monarch's right.

A second is included in 'The True Loyalist or Chevalier's favourite,' surreptitiously printed without a publisher's name. It begins:—

Britannia, rouse at Heav'ns command!

And crown thy native Prince again;

Then Peace shall bless thy happy land,

And plenty pour in from the main;

Then shalt thou be—Britannia, thou shalt be—

From home and foreign tyrants free! etc.

Another is included in the same collection.

A doubt was raised as to the authorship of the words of 'Rule, Britannia!' by Dr. Dinsdale, editor of the re-edition of Mallet's Poems in 1851. Dinsdale claims for Mallet the ballad of 'William and Margaret,' and 'Rule, Britannia!' As to the first claim, the most convincing evidence against Mallet—unknown when Dinsdale wrote—is now to be found in the Library of the British Museum. In 1878 I first saw a copy of the original ballad in an auction room, and, guided by it, I traced a second copy in the British Museum, where it is open to all enquirers. It reproduces the tune, which had been utterly lost in England, as in Scotland, because it was not fitted for dancing, but only for recitation. Until Dinsdale put in a claim for Mallet, 'Rule, Britannia!' had been, universally ascribed to Thomson, from the advertisements of the time down to the 'Scotch Songs' of Ritson—a most careful and reliable authority for facts. Mallet left the question in doubt. Thomson was but recently dead, and consequently many of his surviving friends knew the facts. 'According to the present arrangement of the fable,' says Mallet, 'I was obliged to reject a great deal of what I had written in the other; neither could I retain of my friend's part more than three or four single speeches, and a part of one song.' He does not say that it was the one song of the whole that had stood out of the piece, and had become naturalised, lest his 'friend' should have too much credit, but 'Rule, Britannia!' comes under this description, because he allowed Lord Bolingbroke to mutilate the poem, by substituting three stanzas of his own for the 4th, 5th and 6th of the original. Would Mallet have allowed this mutilation of the poem had it been his own? Internal evidence is strongly in favour of Thomson. See his poems of 'Britannia,' and 'Liberty.' As an antidote to Dinsdale's character of David Mallet, the reader should compare that in Chalmers's 'General Biographical Dictionary.'

Beethoven composed 5 Variations (in D) apon the air of 'Rule, Britannia!' and many minor stars have done the like. [App. p.778 "Add that Wagner wrote an overture in which it is introduced. See vol. iv. p. 373a."][ W. C. ]