A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Schumann, Robert

SCHUMANN, Robert Alexander, born June 8, 1810, at Zwickau in Saxony, was the youngest son of Friedrich August Gottlob Schumann (born 1773), a bookseller, whose father was a clergyman in Saxony, and whose mother, Johanna Christiana (born 1771), was the daughter of Herr Schnabel, Rathschirurgus (surgeon to the town council) at Zeitz. Schumann cannot have received any incitement towards music from his parents; his father, however, took a lively interest in the belles lettres, and was himself known as an author. He promoted his son's leanings towards art in every possible way, with which however his mother seems to have had no sympathy. In the small provincial town where Schumann spent the first eighteen years of his life there was no musician capable of helping him beyond the mere rudiments of the art. There was a talented town-musician, who for several decades was the best trumpeter in the district,[1] but, as was commonly the case, he practised his art simply as a trade. The organist of the Marienkirche, J. G. Kuntzsch, Schumann's first pianoforte teacher, after a few years declared that his pupil was able to progress alone, and that his instruction might cease. He was so impressed with the boy's talent, that when Schumann subsequently resolved to devote himself wholly to art, Kuntzsch prophesied that he would attain to fame and immortality, and that in him the world would possess one of its. greatest musicians. Some twenty years later, in 1845, Schumann dedicated to him his Studies for the Pedal-Piano, op. 56. [See vol. ii. p. 77a.]

His gift for music showed itself early. He began to compose, as he tells us himself, before he was seven. According to this he must have begun to play the piano, at latest, in his sixth year. When he was about eleven, he accompanied at a performance of Friedrich Schneider's 'Weltgericht,' conducted by Kuntzsch, standing up at the piano to do it. At home, with the aid of some young musical companions, he got up performances of vocal and instrumental music which he arranged to suit their humble powers. In more extended circles too, he appeared as a pianoforte-player, and is said to have had a wonderful gift for extempore playing. His father took steps to procure for him the tuition of C. M. von Weber, who had shortly before (1817) been appointed Capellmeister in Dresden. Weber declared himself ready to undertake the guidance of the young genius, but the scheme fell through for reasons unknown. From that time Schumann remained at Zwickau, where circumstances were not favourable to musical progress; he was left to his own instruction, and every inducement to further progress must have come from himself alone. Under these circumstances, a journey made when he was nine years old to Carlsbad, where he first heard a great pianoforte-player—Ignaz Moscheles—must have been an event never to be forgotten; and indeed during his whole life he retained a predilection for certain of Moscheles's works, and a reverence for his person. The influence of the pianoforte technique of Moscheles on him appears very distinctly in the variations published as op. 1.

At the age of ten he entered the 4th class at the Gymnasium (or Academy) at Zwickau, and remained there till Easter, 1828. He had then risen to the 1st class, and left with a certificate of qualification for the University. During this period his devotion to music seems to have been for a time rather less eager, in consequence of the interference of his school-work and of other tastes. Now, at the close of his boyhood, a strong interest in poetry, which had been previously observed in him, but which had meanwhile been merged in his taste for music, revived with increased strength; he rummaged through his father's book-shop, which favoured this tendency, in search of works on the art of poetry; poetical attempts of his own were more frequent, and at the age of 14 Robert had already contributed some literary efforts to a work brought out by his father and called 'Bildergallerie der berühmtesten Menschen aller Volker und Zeiten' (Portrait-gallery of the most famous men of all nations and times). That he had a gift for poetry is evident from two Epithalamia given by Wasielewski (Biographie Schumann's, 3rd ed., Bonn 1880, p. 305). In 1827 he set a number of his own poems to music, and it is worthy of note that it was not by the classical works of Goethe and Schiller that Schumann was most strongly attracted. His favourite writers were Schulze, the tender and rhapsodical author of 'Die bezauberte Rose' (The Enchanted Rose); and the unhappy Franz von Sonnenberg, who went out of his mind; of foreign poets, Byron especially; but above all, Jean Paul, with whose works he made acquaintance in his 17th year (at the same time as with the compositions of Franz Schubert). These poets represent the cycle of views, sentiments and feelings, under whose spell Schumann's poetical taste, strictly speaking, remained throughout his life. And in no musician has the influence of his poetical tastes on his music been deeper than in him.

On March 29, 1828, Schumann matriculated at the University of Leipzig as Studiosus Juris. It would have been more in accordance with his inclinations to have devoted himself at once wholly to art, and his father would no doubt have consented to his so doing; but he had lost his father in 1826, and his mother would not hear of an artist's career. Her son dutifully submitted, although decidedly averse to the study of jurisprudence. Before actually joining the university he took a short pleasure trip into South Germany, in April, 1828. He had made acquaintance in Leipzig with a fellow-student named Gisbert Rosen; and a common enthusiasm for Jean Paul soon led to a devoted and sympathetic friendship. Rosen went to study at Heidelberg, and the first object of Schumann's journey was to accompany him on his way. In Munich he made the acquaintance of Heine, in whose house he spent several hours. On his return journey he stopped at Bayreuth to visit Jean Paul's widow, and received from her a portrait of her husband.

During the first few months of his university life, Schumann was in a gloomy frame of mind. A students' club to which he belonged for a time, struck him as coarse and shallow, and he could not make up his mind to begin the course of study he had selected. A large part of the first half-year had passed by and still—as he writes to his friend—he had been to no college, but 'had worked exclusively in private, that is to say, had played the piano and written a few letters and Jean Pauliads.'

In this voluntary inactivity and solitude the study of Jean Paul must certainly have had a special charm for him. That writer, unsurpassed in depicting the tender emotions, with his dazzling and even extravagant play of digressive fancy, his excess of feeling over dramatic power, his incessant alternations between tears and laughter, has always been the idol of sentimental women and ecstatic youths. 'If everybody read Jean Paul,' Schumann writes to Rosen, 'they would be better-natured, but they would be unhappier; he has often brought me to the verge of desperation, still the rainbow of peace bends serenely above all the tears, and the soul is wonderfully lifted up and tenderly glorified.' In precisely the same way did Gervinus give himself up for a time to the same influence; but his manly and vigorous nature freed itself from the enervating spell. Schumann's artistic nature, incomparably more finely strung, remained permanently subject to it. Even in his latest years he would become violently angry if any one ventured to doubt or criticise Jean Paul's greatness as an imaginative writer, and the close affinity of their natures is umnistakeable. Schumann himself tells us how once, as a child, at midnight, when all the household were asleep, he had in a dream and with his eyes closed, stolen down to the old piano, and played a series of chords, weeping bitterly the while. So early did he betray that tendency to overstrung emotion which found its most powerful nourishment in Jean Paul's writings.

Music, however, is a social art, and it soon brought him back again to human life. In the house of Professor [2]Carus he made several interesting acquaintances, especially that of Marschner, who was then living in Leipzig, and had brought out his 'Vampyr' there in the spring of 1828. His first meeting with Wieck, the father of his future wife, took place in the same year; and Schumann took several pianoforte lessons from him. Several music-loving students met together there, and all kinds of chamber-music were practised. They devoted themselves with especial ardour to the works of Schubert, whose death on Nov. 19, 1828, was deeply felt by Schumann. Impelled by Schubert's example, he wrote at this time 8 Polonaises for four hands; also a Quartet for piano and strings, and a number of songs to Byron's words; all of which remain unpublished. Besides these occupations, he made a more intimate acquaintance with the clavier works of Sebastian Bach. It is almost self-evident that what chiefly fascinated Schumann in Bach's compositions was the mysterious depth of sentiment revealed in them. Were it not so, it would be impossible to conceive of Bach in connection with the chaotic Jean Paul; and yet Schumann himself says that in early life Bach and Jean Paul had exercised the most powerful influence upon him. Considering the way in which his musical education had been left to itself, the fact of his so thoroughly appreciating the wealth and fulness of life in Bach's compositions at a time when Bach was looked upon only as a great contrapuntist, is clear evidence of the greatness of his own genius; which indeed had some affinity with that of Bach. The ingenuity of outward form in Bach's works was neither strange nor unintelligible to him. For although Schumann had hitherto had no instructor in composition, it need scarcely be said that he had long ago made himself familiar with the most essential parts of the composer's art, and that constant practice in composition must have given him much knowledge and skill in this branch of his art.

At Easter, 1829, Schumann followed his friend Rosen to the university of Heidelberg. The young jurists were perhaps tempted thither by the lectures of the famous teacher, A. F. J. Thibaut; but it is evident that other things contributed to form Schumann's resolution: the situation of the town a perfect Paradise the gaiety of the people, and the nearness of Switzerland, Italy and France. A delightful prospect promised to open to him there: 'That will be life indeed!' he writes to his friend; 'at Michaelmas we will go to Switzerland, and from thence who knows where?' On his journey to Heidelberg chance threw him into the society of Willibald Alexis. As they found pleasure in each other's company, Schumann incontinently turned out of his way and went with the poet some distance down the Rhine. Like Marschner, who indeed was somewhat their senior, Alexis had trodden the path which Schumann was destined to follow, and had reached art by way of the law. No doubt this added to Schumann's interest in the acquaintance. It cannot be denied that even in Heidelberg Schumann carried on his legal studies in a very desultory manner, though Thibaut himself was a living proof that that branch of learning could co-exist with a true love and comprehension of music. Only a few years before (in 1825) Thibaut had published his little book, 'Ueber Reinheit der Tonkunst' (On Purity in Musical Art), a work which at that time essentially contributed to alter the direction of musical taste in Germany. Just as in his volume Thibaut attacks the degenerate state of church music, Schumann, at a later date, was destined to take up arms, in word and deed, against the flat insipidity of concert and chamber music. Nevertheless the two men never became really intimate; in one, no doubt, the doctor too greatly preponderated, and in the other the artist. Thibaut himself subsequently advised Schumann to abandon the law and devote himself entirely to music.

Indeed if Schumann was industrious in anything at Heidelberg it was in pianoforte-playing. After practising for seven hours in the day, he would invite a friend to come in the evening and play with him, adding that he felt in a particularly happy vein that day; and even during an excursion with friends he would take a dumb keyboard with him in the carriage. By diligent use of the instruction he had received from Wieck in Leipzig, he brought himself to high perfection as an executant; and at the same time increased his efforts at improvisation. One of his musical associates at this time used afterwards to say that from the playing of no other artist, however great, had he ever experienced such ineffaceable musical impressions; the ideas seem to pour into the player's mind in an inexhaustible flow, and their profound originality and poetic charm already clearly foreshadowed the main features of his musical individuality. Schumann appeared only once in public, at a concert given by a musical society at Heidelberg, where he played Moscheles's variations on the 'Alexandermarsch' with great success. He received many requests to play again, but refused them all, probably, as a student, finding it not convenient.

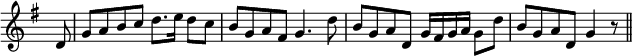

It will no doubt be a matter of surprise that Schumann could have justified himself in thus spending year after year in a merely nominal study of the law, while in fact wholly given up to his favourite taste and pursuit. A certain lack of determination, a certain shrinking from anything disagreeable, betray themselves during these years as his general characteristics, and were perhaps an integral part of his nature. At the same time his conduct is to a certain extent explicable, by the general conditions of German student-life. Out of the strict discipline of the Gymnasium the student steps at once into the unlimited freedom of the University. The violence of the contrast most easily overpowers the most gifted natures, and sweeps them away into an exclusive enjoyment of the life it offers. Those who have some self-control after a time struggle out of the whirlpool, and avail themselves as best they may of the remaining years of study, rescuing from that period a precious store of poetical reminiscences which suffice to gild the prose of later life with an ideal light. It was the intoxicating poetry of the student life which Schumann drank in deep draughts. Its coarseness was repellent to his refined nature, and his innate purity and nobility guarded him against moral degradation; but he lived like a rover rejoicing in this bright world as it lies open to him, worked little, spent much, got into debt, and was as happy as a fish in the water. Besides its tender and rapturous side, his nature had a vein of native sharpness and humour. With all these peculiarities he could live his student's life to the full, though in his own apparently quiet and unassertive way. The letters in which he discusses money-matters with his guardian, Herr Rudel, a merchant of Zwickau, show how he indulged his humorous mood even in these: 'Dismal things I have to tell you, respected Herr Rudel,' he writes on June 21, 1830; 'in the first place, that I have a repetitorium which costs 80 gulden every half-year, and secondly, that within a week I have been under arrest by the town (don't be shocked) for not paying 30 gulden of other college dues.' And on another occasion, when the money he had asked for to make a journey home for the holidays did not arrive: 'I am the only student here, and wander alone about the streets and woods, forlorn and poor, like a beggar, and with debts into the bargain. Be kind, most respected Herr Rudel, and only this once send me some money—only money—and do not drive me to seek means of setting out which might not be pleasant to you.' The reasons he employs to prove to his guardian that he ought not to be deprived of means for a journey into Italy are most amusing: 'At any rate I shall have made the journey; and as I must make it once, it is all the same whether I use the money for it now or later.' Then in a perfectly amiable way he puts the pistol to his breast, 'Of course I could borrow the money here at once if I chose, at 10 or 12 per cent, but this method I should of course adopt only under the most unnatural circumstances, i.e. if I get no money from home.' When, at Easter 1830, he wished to remain another half-year at Heidelberg, he excused the wish by saying that 'residence here is immeasurably more instructive, useful and interesting, than in flat Leipzig.' This contrast of 'flat' Leipzig with the picturesque hilliness of Heidelberg, sufficiently betrays what it was that Schumann included under the terms 'instructive and useful.' His compositions, too, plainly evince how deeply the poetical aspect of student life had affected him, and had left its permanent mark on him. I need only remind the reader of Kerner's 'Wanderlied' (op. 35, no. 3), dedicated to an old fellow-student at Heidelberg, and of Eichendorff's 'Frühlingsfahrt' (op. 45, no. 2). Among German songs of the highest class, there is not one in which the effervescent buoyancy of youth craving for distant flights has found such full expression, at once so thoroughly German and so purely ideal, as in this 'Wanderlied,' which indeed, with a different tune, is actually one of the most favourite of student songs. 'Frühlingsfahrt' tells of two young comrades who quit home for the first time:—

So jubelnd recht in die hellen

Klingeuden, singenden Wellen

Des vollen Frühlings hinaus.

Rejoicing in the singing

And joyous, echoing ringing

Of full and perfect Spring.

One of them soon finds a regular subsistence and a comfortable home; the other pursues glittering visions, yields to the thousand temptations of the world, and finally perishes; it is a portrait of a German student drawn from the life, and the way in which Schumann has treated it shows that he was drawing on the stores of his own experience. And indeed he trod on the verge of the abyss which yawns close to the flowery path of a youth who, for the first time, enjoys complete liberty. His letters often indicate this, particularly one written April 5, 1833, to one of his former fellow-students, in which he says that his life as a citizen is, to his great joy, sober, industrious and steady, and thus a contrast to that at Heidelberg.

Several journeys also served to infuse into Schumann's student life the delight of free and unrestrained movement. In August 1829 he went for a pleasure trip to north Italy, quite alone, for two friends who had intended to go, failed him. But perhaps the contemplative and dreamy youth enjoyed the loveliness of the country and the sympathetic Italian nature only the more thoroughly for being alone. Nor were little adventures of gallantry wanting. Fragments of a diary kept at this time, which are preserved (Wasielewski, p. 325), reveal to us the pleasant sociableness of the life which Schumann now delighted in. The Italian music which he then heard could indeed do little towards his improvement, except that it gave him, for the first time, the opportunity of hearing Paganini. The deep impression made by that remarkable player is shown by Schumann's visit to Frankfort (Easter 1830) with several friends to hear him again, and by his arrangement of his 'Caprices' for the pianoforte (op. 3 and 10). Shortly after this he seems to have heard Ernst also in Frankfort. In the summer of 1830 he made a tour to Strassburg, and on the way back to Saxony visited his friend Rosen at Detmold.

When Schumann entered upon his third year of study, he made a serious effort to devote himself to jurisprudence; he took what was called a Repetitorium, that is, he began going over again with considerable difficulty, and under the care and guidance of an old lawyer, what he had neglected during two years. He also endeavoured to reconcile himself to the idea of practical work in public life or the government service. His spirit soared up to the highest goal, and at times he may have flattered his fancy with dreams of having attained it; but he must have been convinced of the improbability of such dreams ever coming true; and indeed he never got rid of his antipathy to the law as a profession, even in the whole course of his Repetitorium. On the other hand it must be said, that if he was ever to be a musician, it was becoming high time for it, since he was now 20 years old. Thus every consideration urged him to the point. Schumann induced his mother, who was still extremely averse to the calling of a musician, to put the decision in the hands of Friedrich Wieck. Wieck did not conceal from him that such a step ought only to be taken after the most thorough self-examination, but if he had already examined himself, then Wieck could only advise him to take the step. Upon this his mother yielded, and Robert Schumann became a musician. The delight and freedom which he inwardly felt when the die was cast, must have shown him that he had done right. At first his intention was only to make himself a great pianoforte-player, and he reckoned that in six years he would be able to compete with any pianist. But he still felt very uncertain as to his gift as a composer; the words which he wrote to his mother on July 30, 1830—'Now and then I discover that I have imagination, and perhaps a turn for creating things myself'—sound curiously wanting in confidence, when we remember how almost exclusively Schumann's artistic greatness was to find expression in his compositions.

He quitted Heidelberg late in the summer of 1830, in order to resume his studies with Wieck in Leipzig. He was resolved, after having wasted two years and a half, to devote himself to his new calling with energetic purpose and manly vigour. And faithfully did he keep to his resolution. The plan of becoming a great pianist had, however, to be given up after a year. Actuated by the passionate desire to achieve a perfect technique as speedily as possible, Schumann devised a contrivance by which the greatest possible dexterity of finger was to be attained in the shortest time. By means of this ingenious appliance the third finger was drawn back and kept still, while the other fingers had to practice exercises. But the result was that the tendons of the third finger were overstrained, the finger was crippled, and for some time the whole right hand was injured. This most serious condition was alleviated by medical treatment. Schumann recovered the use of his hand, and could, when needful, even play the piano; but the third finger remained useless, so that he was for ever precluded from the career of a virtuoso. Although express evidence is wanting, we may assume with certainty that this unexpected misfortune made a deep impression upon him; he saw himself once more confronted with the question whether it was advisable for him to continue in the calling he had chosen. That he answered it in the affirmative shows that during this time his confidence in his own creative genius had wonderfully increased. He soon reconciled himself to the inevitable, learned to appreciate mechanical dexterity at its true value, and turned his undivided attention to composition. He continued henceforth in the most friendly relations with his pianoforte-master, Wieck; indeed until the autumn of 1832 he lived in the same house with him (Grimmaische Strasse, No. 36), and was almost one of the family. For his instructor in composition, however, he chose Heinrich Dorn, at that time conductor of the opera in Leipzig, subsequently Capellmeister at Riga, Cologne, and Berlin, and still living in Berlin in full possession of his intellectual vigour. Dorn was a clever and sterling composer; he recognised the greatness of Schumann's genius, and devoted himself with much interest to his improvement.[3] It was impossible as yet to confine Schumann to a regular course of composition: he worked very diligently, but would take up now one point of the art of composition and now another. In 1836 he writes to Dorn at Riga that he often regrets having learnt in too irregular a manner at this time; but when he adds directly afterwards that, notwithstanding this, he had learnt more from Dorn's teaching than Dorn would believe, we may take this last statement as true. Schumann was no longer a tyro in composition, but had true musical genius, and his spirit was already matured. Under such circumstances he was justified in learning in his own way.

In the winter of 1832–3, he lived at Zwickau, and for a time also with his brothers at Schneeberg. Besides a pianoforte concerto, which still remains a fragment, he was working at a symphony in G minor, of which the first movement was publicly performed in the course of the winter both at Schneeberg and Zwickau. If we may trust certain evidence (see 'Musikalisches Wochenblatt'; Leipzig, 1875, p. 180), the whole symphony was performed at Zwickau in 1835, under Schumann's own direction, and the last movement was almost a failure.

At all events the symphony was finished, and Schumann expected it to be a great success; in this he must have been disappointed, for it has never been published. The first performance of the first movement at Zwickau took place at a concert given there on Nov. 18, 1832, by Wieck's daughter Clara, who was then thirteen years of age. Even then the performances of this gifted girl, who was so soon to take her place as the greatest female pianist of Germany, were astonishing, and by them, as Schumann puts it, 'Zwickau was fired with enthusiasm for the first time in its life.' It is easily conceivable that Schumann himself was enthusiastically delighted with Clara, adorned as she was with the twofold charm of childlike sweetness and artistic genius. 'Think of perfection,' he writes to a friend about her on April 5, 1833, 'and I will agree to it.' And many expressions in his letters seems even to betray a deeper feeling, of which he himself did not become fully aware until several years later.

Schumann's circumstances allowed him to revisit Leipzig in March, 1833, and even to live there for a time without any definite occupation. He was not exactly well off, but he had enough to enable him to live as a single man of moderate means. The poverty from which so many of the greatest musicians have suffered, never formed part of Schumann's experience. He occupied himself with studies in composition, chiefly in the contrapuntal style, in which he had taken the liveliest interest since making the acquaintance of Bach's works; besides this his imagination, asserting itself more and more strongly, impelled him to the creation of free compositions. From this year date the impromptus for piano on a romance by Clara Wieck, which Schumann dedicated to her father, and published in August, 1833, as op. 5.[4] In June he wrote the first and third movements of the G minor Sonata (op. 22), and at the same time began the F♯ minor Sonata (op. 11) and completed the Toccata (op. 7), which had been begun in 1829. He also arranged a second set of Paganini's violin caprices for the piano (op. 10), having made a first attempt of the same kind (op. 3) in the previous year. Meanwhile he lived a quiet and almost monotonous life. Of family acquaintances he had few, nor did he seek them. He found a faithful friend in Frau Henriette Voigt, who was as excellent a pianist as she was noble and sympathetic in soul. She was a pupil of Ludwig Berger, of Berlin, and died young in the year 1839. Schumann was wont as a rule to spend his evenings with a small number of intimate friends in a restaurant. These gatherings generally took place at the 'Kaffeebaum' (Kleine Fleischergasse No. 3). He himself however generally remained silent by preference, even in this confidential circle of friends. Readily as he could express himself with his pen, he had but little power of speech. Even in affairs of no importance, which could have been transacted most readily and simply by word of mouth, he usually preferred to write. It was moreover a kind of enjoyment to him to muse in dreamy silence. Henriette Voigt told W. Taubert that one lovely summer evening, after making music with Schumann, they both felt inclined to go on the water. They sat side by side in the boat for an hour in silence. At parting Schumann pressed her hand and said, 'To-day we have perfectly understood one another.'

It was at these evening gatherings at the restaurant in the winter of 1833–4 that the plan of starting a new musical paper was matured. It was the protest of youth, feeling itself impelled to new things in art, against the existing state of music. Although Weber, Beethoven, and Schubert had only been dead a few years, though Spohr and Marschner were still in their prime, and Mendelssohn was beginning to be celebrated, the general characteristic of the music of about the year 1830 was either superficiality or else vulgar mediocrity. 'On the stage Rossini still reigned supreme, and on the pianoforte scarcely anything was heard but Herz and Hünten.' Under these conditions the war might have been more suitably carried on by means of important works of art than by a periodical about music. Musical criticism, however, was itself in a bad way at this time. The periodical called 'Cæcilia,' published by Schott, which had been in existence since 1824, was unfitted for the general reader, both by its contents and by the fact of its publication in parts. The 'Berliner allgemeine musikalische Zeitung,' conducted by Marx, had come to an end in 1830. The only periodical of influence and importance in 1833 was the 'Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung,' published by Breitkopf & Härtel of Leipzig, and at that time edited by G. W. Fink. But the narrow view taken of criticism in that periodical, its inane mildness of judgment—Schumann used to call it 'Honigpinselei' or 'Honey-daubing'—its lenity towards the reigning insipidity and superficiality, could not but provoke contradiction from young people of high aims. And the idea of first bringing the lever to bear on the domain of critical authorship, in order to try their strength, must have been all the more attractive to these hot-headed youths, since most of them had had the advantage of a sound scholarly education and knew how to handle their pens. On the other hand, they felt that they were not yet strong enough to guide the public taste into new paths by their own musical productions; and of all the set Schumann was the most sensible of this fact.

Such were the grounds on which, on April 3, 1834, the first number of the 'Neue Zeitschrift für Musik' saw the light. Schumann himself called it the organ of youth and movement. As its motto he even chose this passage from the prologue to Shakespeare's Henry VIII:—

Only they

Who come to hear a merry bawdy play,

A noise of targets, or to see a fellow

In a long motley coat guarded with yellow,

Will be deceived—

a passage which sufficiently expresses his intention of contending against an empty flattering style of criticism, and upholding the dignity of art. 'The day of reciprocal compliments,' says the preliminary notice, 'is gradually dying out, and we must confess that we shall do nothing towards reviving it. The critic who dares not attack what is bad, is but a half-hearted supporter of what is good.' The doings of 'the three archfoes of art—those who have no talent, those who have vulgar talent, and those who having real talent, write too much,' are not to be left in peace; 'their latest phase, the result of a mere cultivation of executive technique,' is to be combatted as inartistic. 'The older time,' on the other hand, 'and the works it produced, are to be recalled with insistance, since it is only at these pure sources that new beauties in art can be found.' Moreover the 'Zeitschrift' is to assist in bringing in a new 'poetic' period by its benevolent encouragement of the higher efforts of young artists, and to accelerate its advent. The editing was in the hands of Robert Schumann, Friedrich Wieck, Ludwig Schunke, and Julius Knorr.

Of all these Schunke alone was exclusively a musician. That gifted pianist, who belonged to a widely dispersed family of esteemed musicians, came to Leipzig in 1833, and became a great friend of Schumann's, but died at the end of the following year at the early age of 24. The three other editors were by education half musicians and half littérateurs, even Julius Knorr (born 1807) having studied philology in Leipzig. Schumann co-operated largely in Schunke's contributions (signed with the figure 3), for handling the pen was not easy to him. Hartmann of Leipzig was at first the publisher and proprietor of the Zeitschrift, but at the beginning of 1835 it passed into the hands of J. A. Barth of Leipzig, Schumann becoming at the same time proprietor and sole editor. He continued the undertaking under these conditions till the end of June 1844; so that his management of the paper extended over a period of above ten years. On Jan. 1, 1845, Franz Brendel became the editor, and after the summer of 1844 Schumann never again wrote for it, with the exception of a short article[5] on Johannes Brahms to be mentioned hereafter.

Schumann's own articles are sometimes signed with a number—either 2 or some combination with 2, such as 12, 22, etc. He also concealed his identity under a variety of names—Florestan, Eusebius, Raro, Jeanquirit. In his articles we meet with frequent mention of the Davidsbündler, a league or society of artists or friends of art who had views in common. This was purely imaginary, a half-humorous, half-poetical fiction of Schumann's, existing only in the brain of its founder, who thought it well fitted to give weight to the expression of various views of art, which were occasionally put forth as its utterances. The idea betrays some poetic talent, since in this way mere critical discussions gain the charm of dramatic life. The characters which most usually appear are Florestan and Eusebius, two personages in whom Schumann endeavoured to embody the two opposite sides of his nature. The vehement, stormy, rough element is represented by Florestan; the gentler and more poetic one by Eusebius. These two figures are obviously imitated from Vult and Walt in Jean Paul's 'Flegeljahre'; indeed Schumann's literary work throughout is strongly coloured with the manner of Jean Paul, and frequent reference is made to his writings. Now and then, as moderator between these antagonistic characters, who of course take opposite views in criticism, 'Master Raro' comes in. In him Schumann has conceived a character such as at one time he had himself dreamed of becoming. The explanation of the name 'Davidsbündler' is given at the beginning of a 'Shrove Tuesday discourse' by Florestan in the year 1835. 'The hosts of David are youths and men destined to slay all the Philistines, musical or other.' In the college-slang of Germany the 'Philistine' is the non-student, who is satisfied to live on in the ordinary routine of every-day life, or—which comes to the same thing in the student's mind—the man of narrow, sober, prosaic views, as contrasted with the high-flown poetry and enthusiasm of the social life of a German university. Thus, in the name of Idealism, the 'Davidsbündler' wage war against boorish mediocrity, and when Schumann regarded it as the function of his paper to aid in bringing in a new 'poetical phase' in music he meant just this. Though Schumann was himself the sole reality in the 'Davidsbündlerschaft,' he indulged his fancy by introducing personages of his acquaintance whose agreement with his views he was sure of. He quietly included all the principal co-operators in the Zeitschrift, and even artists such as Berlioz, whom he did not know, but in whom he felt an interest, and was thus justified in writing to A. von Zuccamaglio in 1836:—'By the Davidsbund is figured an intellectual brotherhood which ramifies widely, and I hope may bear golden fruit.' He brings in the brethren, who are not actually himself, from time to time in the critical discussions; and the way in which he contrives to make this motley troupe of romantic forms live and move before the eyes of the reader is really quite magical. He could say with justice:—'We are now living a romance the like of which has perhaps never been written in any book.' We meet with a Jonathan, who may perhaps stand for Schunke (on another occasion however Schumann designates himself by this name); a Fritz Friedrich, probably meant for Lyser[6] the painter, a lover of music; Serpentin is Carl Banck, a clever composer of songs, who at the outset was one of his most zealous and meritorious fellow-workers; Gottschalk Wedel is Anton von Zuccamaglio [App. p.791 "Zuccalmagio"], then living in Warsaw, who had made a name by his collection of German and foreign 'Volkslieder'; Chiara is of course Clara Wieck, and Zilia (apparently shortened from Cecilia) is probably the same. Felix Mendelssohn appears under the name of Felix Meritis, and the name Walt occurs once (in 1836, 'Aus den Büchern der Davidsbündler,' ii. Tanzlitteratur). It cannot be asserted that any particular person was meant, still his direct reference to Jean Paul's 'Flegeljahre' is interesting. There is also a certain Julius among the 'Davidsbündler,' probably Julius Knorr. The name occurs in Schumann's first essay on music, 'Ein opus ii.' This is not included in the 'Neue Zeitschrift,' but appears in No. 49 of the 'Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung' for 1831 (then edited by Fink). The editor has prefixed a note to the effect that 'it is by a young man, a pupil of the latest school, who has given his name,' and contrasts it with the anonymous work of a reviewer of the old school discussing the same piece of music. The contrast is indeed striking, and the imaginative flights of enthusiastic young genius look strange enough among the old-world surroundings of the rest of the paper.

Schumann placed this critique—which deals with Chopin's variations on 'La ci darem'—at the beginning of his collected writings, which he published towards the close of his life ('Gesammelte Schriften,' 4 vols. GeorgWigand, Leipzig, 1854). It is a good example of the tone which he adopted in the 'Neue Zeitschrift.' His fellow-workers fell more or less into the same key, not from servility, but because they were all young men, and because the reaction against the Philistine style of criticism was just then in the air. This may be plainly detected, for instance, in a critique written by Wieck for the periodical called 'Cecilia,' on Chopin's airs with variations, and which is indeed fanciful enough. Thus it is easy to understand that the total novelty of the style of writing of the 'Neue Zeitschrift' should have attracted attention to music; the paper soon obtained a comparatively large circulation; and as, besides the charm of novelty and style, it offered a variety of instructive and entertaining matter, and discussed important subjects earnestly and cleverly, the interest of the public was kept up, and indeed constantly increased from year to year. The influence exerted by Schumann on musical art in Germany through the medium of this paper, cannot but be regarded as very important.

It has been sometimes said that Schumann's literary labours must have done him mischief, by taking up time and energy which might have been better employed in composition. But this view seems to me untenable. Up to the period at which we have now arrived, Schumann, on his own statement, had merely dreamed away his life at the piano. His tendency to self-concentration, his shyness, and his independent circumstances, placed him in danger of never achieving that perfect development of his powers which is possible only by vigorous exercise. Now the editing of a journal is an effectual remedy for dreaming; and when, at the beginning of 1835, he became sole editor, however much he may have felt the inexorable necessity of satisfying his readers week after week, and of keeping his aim constantly in view, it was no doubt a most beneficial exercise for his will and energies. He was conscious of this, or he certainly would not have clung to the paper with such affection and persistency; and it is a matter of fact that the period of his happiest and most vigorous creativeness coincides pretty nearly with that during which he was engaged on the 'Zeitschrift.' Hence, to suppose that his literary work was any drawback to his artistic career is an error, though it is true that as he gradually discovered the inexhaustible fertility of his creative genius, he sometimes complained that the details of an editor's work were a burthen to him. Besides, the paper was the medium by which Schumann was first brought into contact and intercourse with the most illustrious artists of his time; and living as he did apart from all the practically musical circles of Leipzig, it was almost the only link between himself and the contemporary world.

Nor must we overlook the fact that certain peculiar gifts of Schumann's found expression in his writings on musical subjects, gifts which would otherwise scarcely have found room for display. His poetic talent was probably neither rich enough nor strong enough for the production of large independent poems; but, on the other hand, it was far too considerable to be condemned to perpetual silence. In his essays and critiques, which must be regarded rather as poetic flights and sympathetic interpretations than as examples of incisive analysis, his poetical gift found a natural outlet, and literature is by so much the richer for them. Nay, it is a not unreasonable speculation whether, if his imaginative powers had not found this vent they might not have formed a disturbing and marring element in his musical creations. Even as it is, poetical imagery plays an important part in Schumann's music, though without seriously overstepping the permissible limits. This too we may safely say, that in spite of his silent and self-contained nature, there was in Schumann a vein of the genuine agitator, in the best and noblest sense of the word; he was possessed by the conviction that the development of German art, then in progress, had not yet come to its final term, and that a new phase of its existence was at hand. Throughout his writings we find this view beautifully and poetically expressed, as for instance, 'Consciously or unconsciously a new and as yet undeveloped school is being founded on the basis of the Beethoven-Schubert romanticism, a school which we may venture to expect will mark a special epoch in the history of art. Its destiny seems to be to usher in a period which will nevertheless have many links to connect it with the past century.' Or again: 'A rosy light is dawning in the sky; whence it cometh I know not; but in any case, O youth, make for the light.'

To rouse fresh interest and make use of that already existing for the advancement of this new movement was one of his deepest instincts, and this he largely accomplished by means of his paper. From his pen we have articles on almost all the most illustrious composers of his generation—Mendelssohn, Taubert, Chopin, Hiller, Heller, Henselt, Sterndale-Bennett, Gade, Kirchner, and Franz, as well as Johannes Brahms, undoubtedly the most remarkable composer of the generation after Schumann. On some he first threw the light of intelligent and enthusiastic literary sympathy; others he was actually the first to introduce to the musical world; and even Berlioz, a Frenchman, he eulogised boldly and successfully, recognising in him a champion of the new idea. By degrees he would naturally discern that he had thus prepared the soil for the reception of his own works. He felt himself in close affinity with all these artists, and was more and more confirmed in his conviction that he too had something to say to the world that it had not heard before. 'If you only knew,' he wrote in 1836 to Moscheles in London, 'how I feel, as though I had reached but the lowest bough of the tree of heaven; and could hear overhead, in hours of sacred loneliness, songs, some of which I may yet reveal to those I love—you surely would not deny me an encouraging word.' In the Zeitschrift he must have been aware that he controlled a power which would serve to open a shorter route for his own musical productions. 'If the publisher were not afraid of the editor, the world would hear nothing of me—perhaps to the world's advantage. And yet the black heads of the printed notes are very pleasant to behold.' 'To give up the paper would involve the loss of all the reserve force which every artist ought to have if he is to produce easily and freely.'

So he wrote in 1836 and 1837. But at the same time we must emphatically contradict the suggestion that Schumann used his paper for selfish ends. His soul was too entirely noble and his ideal aims too high to have any purpose in view but the advancement of art; and it was only in so far as his own interests were inseparable from those of his whole generation, that he would ever have been capable of forwarding the fortunes of his own works. The question even whether, and in what manner, his own works should be discussed in the Neue Zeitschrift he always treated with the utmost tact. In one of his letters he clearly expresses his principles on the subject as follows: 'I am, to speak frankly, too proud to attempt to influence Härtel through Fink (editor of the 'Allgemeine mus. Zeitung'); and I hate, at all times, any mode of instigating public opinion by the artist himself. What is strong enough works its own way.'

His efforts for the good cause indeed went beyond essay-writing and composing. Extracts from a note-book published by Wasielewski prove that he busied himself with a variety of plans for musical undertakings of general utility. Thus he wished to compile lives of Beethoven and of Bach, with a critique of all their works, and a biographical dictionary of living musicians, on the same plan. He desired that the relations of operatic composers and managers should be regulated by law. He wished to establish an agency for the publication of musical works, so that composers might derive greater benefit from their publications, and gave his mind to a plan for founding a Musical Union in Saxony, with Leipzig as its head-quarters, to be the counterpart of Schilling's National German Union (Deutschen National Verein fur Musik).

In the first period of his editorship, before he had got into the way of easily mastering his day's labour, and when the regular round of work had still the charm of novelty, it was of course only now and then that he had leisure, or felt in the mood, for composing. Two great pianoforte works date from 1834 (the 'Carnaval,' op. 9, and the 'Etudes Symphoniques,' op. 13), but in 1835 nothing was completed. After this, however, Schumann's genius began again to assert itself, and in the years 1836 to 1839 he composed that splendid set of pianoforte works of the highest excellence, on which a considerable part of his fame rests; viz. the great Fantasia (op. 17), the F minor Sonata (op. 14), Fantasiestücke (op. 12), Davidsbündlertänze, Novelletten, Kinderscenen, Kreisleriana, Humoreske, Faschingsschwank, Romanzen, and others. The fount of his creative genius flowed forth ever clearer and more abundantly. 'I used to rack my brains for a long time,' writes he on March 15, 1839, 'but now I scarcely ever scratch out a note. It all comes from within, and I often feel as if I could go playing straight on without ever coming to an end.' The influence of Schumann the author on Schumann the composer may often be detected. Thus the 'Davidsbündler' come into his music, and the composition which bears their name was originally entitled 'Davidsbündler dances for the Pianoforte, dedicated to Walther von Goethe by Florestan and Eusebius.' The title of the F♯ minor Sonata, op. 11, which was completed in 1835, runs thus: 'Pianoforte Sonata. Dedicated to Clara by Florestan and Eusebius.' In the 'Carnaval,' a set of separate and shorter pieces with a title to each, the names of Florestan and Eusebius occur again, as do those of Chiarina (the diminutive of Clara), and Chopin; the whole concluding with a march of the Davidsbündler against the Philistines.

The reception of Schumann's works by the critics was most favourable and encouraging, but the public was repelled by their eccentricity and originality; and it was not till after the appearance of the 'Kinderscenen' (1839) that they began to be appreciated. Ops. 1 and 2 actually had the honour of a notice in the Vienna 'Musikalische Zeitung' of 1832, by no less a person than Grillparzer the poet. Fink designedly took hardly any notice of Schumann in the 'Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung.' But Liszt wrote a long, discriminating, and very favourable article in the 'Gazette Musicale' of 1837 upon the Impromptus (op. 5), and the Sonatas in F♯ minor and F minor. Moscheles wrote very sympathetically on the two sonatas in the 'Neue Zeitschrift für Musik' itself (vols 5 and 6), and some kind words of recognition of Schumann's genius were published subsequently from his diary (Moscheles's 'Leben,' Leipzig, 1873, vol. ii. p. 15; English translation by A. D. Coleridge, vol. ii. p. 19, 20). Other musicians, though not expressing their sentiments publicly, continued to hold aloof from him. Hauptmann at that time calls Schumann's pianoforte compositions 'pretty and curious little things, all wanting in proper solidity, but otherwise interesting.' (See Hauptmann's Letters to Hauser, Leipzig, 1871, vol. i. p. 255.)

In October 1835 the musical world of Leipzig was enriched by the arrival of Mendelssohn. It was already in a flourishing state: operas, concerts, and sacred performances alike were of great excellence, and well supported by the public. But although the soil was well prepared before Mendelssohn's arrival, it was he who raised Leipzig to the position of the most musical town of Germany. The extraordinarily vigorous life that at once grew up there under the influence of his genius, drawing to itself from far and near the most important musical talent of the country, has shown itself to be of so enduring a character that even at the present day its influences are felt. Schumann too, who had long felt great respect for Mendelssohn, was drawn into his circle. On Oct. 4, 1835, Mendelssohn conducted his first concert in the Gewandhaus; the day before this there was a musical gathering at the Wiecks', at which both Mendelssohn and Schumann were present, and it seems to have been on this occasion that the two greatest musicians of their time first came into close personal intercourse. (Moscheles's 'Leben,' i. 301; English translation, i. 322.) On Oct. 5, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Moscheles, Banck, and a few others, dined together. In the afternoon of the 6th there was again music at Wieck's house; Moscheles, Clara Wieck, and L. Rakemann from Bremen, played Bach's D minor Concerto for three claviers, Mendelssohn putting in the orchestral accompaniments on a fourth piano. Schumann, who was also present, writes in the 'Zeitschrift,' 'It was splendid to listen to.' Moscheles had come over from Hamburg, where he was staying on a visit, to give a concert in Leipzig. Schumann had already been in correspondence with him, but this was the first opportunity he had enjoyed of making the personal acquaintance of the man whose playing had so delighted him in Carlsbad when a boy of 9. Moscheles describes him as 'a retiring but interesting young man,' and the F♯ minor Sonata, played to him by Clara Wieck, as 'very laboured, difficult, and somewhat intricate, although interesting.'

A livelier intimacy, so far as Schumann was concerned, soon sprang up between him and Mendelssohn. When Mendelssohn had to go to Düsseldorf in May 1836, to the first performance of 'St. Paul' at the Niederrheinische Musikfest, Schumann even intended to go with him, and was ready months beforehand, though when the time arrived he was prevented from going. They used to like to dine together, and gradually an interesting little circle was formed around them, including among others Ferdinand David, whom Mendelssohn had brought to Leipzig as leader of his orchestra. In the early part of January 1837 Mendelssohn and Schumann used in this way to meet every day and interchange ideas, so far as Schumann's silent temperament would allow. Subsequently when Mendelssohn was kept more at home by his marriage, this intercourse became rarer. Schumann was by nature unsociable, and at this time there were outward circumstances which rendered solitude doubly attractive to him. Ferdinand Hiller, who spent the winter of 1839–40 in Leipzig with Mendelssohn, relates that Schumann was at that time living the life of a recluse and scarcely ever came out of his room. Mendelssohn and Schumann felt themselves drawn together by mutual appreciation. The artistic relations between the two great men were not as yet, however, thoroughly reciprocal. Schumann admired Mendelssohn to the point of enthusiasm. He declared him to be the best musician then living, said that he looked up to him as to a high mountain-peak, and that even in his daily talk about art some thought at least would be uttered worthy of being graven in gold. And when he mentions him in his writings, it is in a tone of enthusiastic admiration, which shows in the best light Schumann's fine ideal character, so remarkable for its freedom from envy. And his opinion remained unaltered: in 1842 he dedicated his three string quartets to Mendelssohn, and in the 'Album für die Jugend' there is a little piano piece called 'Erinnerung,' dated Nov. 4, 1847, which shows with eloquent simplicity how deeply he felt the early death of his friend. It is well known how he would be moved out of his quiet stillness if he heard any disparaging expression used of Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn, on the contrary, at first only saw in Schumann the man of letters and the art-critic. Like most productive musicians, he had a dislike to such men as a class, however much he might love and value single representatives, as was really the case with regard to Schumann. From this point of view must be regarded the expressions which he makes use of now and then in letters concerning Schumann as an author. (See Mendelssohn's 'Briefe,' ii. 116; Lady Wallace's translation ii. 97;[7] and Hiller's 'Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy,' Cologne, 1878, p. 64.) If they sound somewhat disparaging, we must remember that it is not the personal Mendelssohn speaking against the personal Schumann, but rather the creative artist speaking against the critic, always in natural opposition to him. Indeed it is obviously impossible to take such remarks in a disadvantageous sense, as Schumann quite agreed with Mendelssohn on the subject of criticism. One passage in his writings is especially remarkable in this respect. He is speaking of Chopin's pianoforte concerto, and Florestan exclaims 'What is a whole year of a musical paper compared to a concerto by Chopin? What is a magister's rage compared to the poetic frenzy? What are ten complimentary addresses to the editor compared to the Adagio in the second Concerto? And believe me, Davidites, I should not think you worth the trouble of talking to, did I not believe you capable of composing such works as those you write about, with the exception of a few like this concerto. Away with your musical journals! It should be the highest endeavour of a just critic to render himself wholly unnecessary; the best discourse on music is silence. Why write about Chopin? Why not create at first hand—play, write, and compose?' ('Gesammelte Schriften,' i. 276; Engl. trans, in 'Music and Musicians,' series i. p. 205.) True, this impassioned outburst has to be moderated by Eusebius. But consider the significance of Schumann's writing thus in his own journal about the critic's vocation! It plainly shows that he only took it up as an artist, and occasionally despised it. But with regard to Schumann's place in art, Mendelssohn did not, at that time at all events, consider it a very high one, and he was not alone in this opinion. It was shared, for example, by Spohr and Hauptmann. In Mendelssohn's published letters there is no verdict whatever on Schumann's music. The fact however remains that in Schumann's earlier pianoforte works he felt that the power or the desire for expression in the greater forms was wanting, and this he said in conversation. He soon had reason to change his opinion, and afterwards expressed warm interest in his friend's compositions. Whether he ever quite entered into the individualities of Schumann's music may well be doubted; their natures were too dissimilar. To a certain extent the German nation has recovered from one mistake in judgment; the tendency to elevate Schumann above Mendelssohn was for a very long time unmistakable. Latterly their verdict has become more just, and the two are now recognised as composers of equal greatness.

Schumann's constant intimacy in Wieck's house had resulted in a tender attachment to his daughter Clara, now grown up. So far as we know it was in the spring of 1836 that this first found any definite expression. His regard was reciprocated, and in the summer of the following year he preferred his suit formally to her father. Wieck however did not favour it; possibly he entertained loftier hopes for his gifted daughter. At any rate he was of opinion that Schumann's means and prospects were too vague and uncertain to warrant his setting up a home of his own. Schumann seems to have acknowledged the justice of this hesitation, for in 1838 he made strenuous efforts to find a new and wider sphere of work. With the full consent of Clara Wieck he decided on settling in Vienna, and bringing out his musical periodical in that city. The glory of a great epoch still cast a light over the musical life of the Austrian capital—the epoch when Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert were living and working there. In point of fact, all genuine music had vanished even during Beethoven's lifetime, and had given way to a trivial and superficial taste. Rossini and his followers were paramount in opera; in orchestral music there were the waltzes of Strauss and Lanner; and in vocal music the feeble sentimentalities of Proch and his fellow-composers. So far as solo playing was concerned, the fourth decade of the century saw it at its highest pitch of executive brilliancy, and its lowest of purpose and feeling—indeed it may be comprehensively designated as the epoch of Thalberg. Thus Schumann would have found in Vienna ample opportunity for doing good work, for the Viennese public was still as ever the most responsive in the world, and one to justify sanguine hopes. Schumann effected his move with the assistance of Professor Joseph Fischhof, his colleague in the paper; settling himself in Oct. 1838 in the Schönlaterngasse, No. 679. Oswald Lorenz edited the 'Zeitschrift' as Schumann's deputy, and for a time it was still to be issued in Leipzig. Schumann hoped to be able to bring it out in Vienna by Jan. 1839, and made every effort to obtain the prompt permission of the authorities, as well as the support of influential persons for himself and his journal. But the consent of the censor's office and the police were long withheld; and he was required to secure the co-operation of an Austrian publisher, in itself a great difficulty. It is hard to believe that in the great city of Vienna no strictly musical newspaper then existed, and that a small catalogue, the 'Allgemeine musikalischer Anzeiger,' published weekly by Tobias Haslinger, and almost exclusively devoted to the business interests of his firm, was the only publication which could pretend to the name. But the publishers were either too indolent or too timid to attempt any new enterprise, and sought to throw impediments in Schumann's way.

His courage and hopefulness were soon much reduced. The superficially kind welcome he met everywhere could not conceal the petty strife of coteries, the party spirit and gossip of a society which might have been provincial. The public, though keenly alive to music, was devoid of all critical taste. 'He could not get on with these people,' he writes to Zuccamaglio as early as Oct. 19, 1838; their utter insipidity was at times too much for him, and while he had hoped that on its appearance in Vienna the 'Zeitschrift' would have received a fresh impulse, and become a medium of intercourse between North and South, he was forced as early as December to say: 'The paper is evidently falling off, though it must be published here; this vexes me much.' Sterndale Bennett, who was residing in Leipzig during 1837–8, and who, Schumann hoped, would settle with him in Vienna, was obliged to relinquish his intention; and in Vienna itself he sought in vain for an artist after his own heart, 'one who should not merely play tolerably well on one or two instruments, but who should be a whole man, and understand Shakespeare and Jean Paul.' At the same time he did not abandon the scheme of making a wide and influential circle of activity for himself; he was unwilling to return to Leipzig, and when in March 1839 he made up his mind to do so, after trying in vain to carry on the journal in Vienna, it was with the intention of remaining there but a short time. He indulged in a dream of going to England never to return! What the anticipations could have been that led him tocherish such an idea we know not; perhaps his friendship for Bennett may have led to it; but, in point of fact, he never set foot on English ground.

As far, therefore, as making a home for himself went, his half-year's stay in Vienna was without result. But without doubt Schumann received impulses and incitements towards further progress as a musician through his acquaintance with Vienna life. A work which is to be referred directly to this influence is the 'Faschingsschwank aus Wien' (op. 26, published by Spina in 1841). In the first movement, which seems to depict various scenes of a masquerade, there springs up quite unnoticed the melody of the 'Marseillaise' (p. 7, bar 40 etc.; Pauer's edition, vol. iii. p. 596, l. i), at that time strictly forbidden in Vienna. Schumann, who had been much worried by the government officials on account of his newspaper, took this opportunity of playing off a good-tempered joke upon them.

It was very natural that, with his enthusiastic admiration for Schubert, he should take pains to follow out the traces of that master, who had now been dead just ten years. He visited the Wahring cemetery, where Schubert is buried, divided by a few intervening graves from Beethoven. On the tomb of the latter a steel pen was lying; this Schumann took possession of, and being always fond of symbolical associations and mystic connections, used on very special occasions. With it he wrote his Symphony in B♭ (op. 38), and the notice of Schubert's C major Symphony, which is found in the 'Zeitschrift' for 1840.[8] And here we encounter one of the chief benefits which Schumann received from his stay in Vienna. He visited Franz Schubert's brother Ferdinand, who showed him the artistic remains of his too early lost brother, and among them the score of the C major Symphony. This he had composed in March 1828, but never lived to hear it performed entire, and no one had since cared to take any trouble about it. Schumann arranged for the score to be sent to Leipzig, and there on March 21, 1839, it was performed for the first time under Mendelssohn's direction. Its success was very striking, and was of great influence on the more thorough and widespread appreciation of Schubert's genius. Schumann retained pleasant memories of Vienna throughout his life, in spite of the little notice he attracted on this occasion, and the meagre success of a concert consisting of his own works, which he gave with his wife on a subsequent visit in the winter of 1846. In the summer of 1847 he even wished to apply for a vacant post on the board of direction at the Conservatorium, but when the year 1848 came, he was extremely glad that the plan had come to nothing.

At the beginning of April 1839 Schumann returned to his old life in Leipzig. He devoted himself with new zest to the interests of the journal, and delighted in once more being associated with prominent and sympathetic musicians. In the summer he paid a short visit to Berlin, which pleased and interested him from its contrast to Vienna.

Unfortunately Wieck's opinion as to the match between Schumann and his daughter remained unchanged, and his opposition to it became even stronger and more firmly rooted. Since persuasion was unavailing, Schumann was forced to call in the assistance of the law, and Wieck had to account for his refusal in court. The case dragged on for a whole year, but the final result was that Wieck's objections to the marriage were pronounced to be trivial and without foundation. A sensitive nature such as Schumann's must have been deeply pained by these difficulties, and the long-delayed decision must have kept him in disastrous suspense. His letters show signs of this. For the rest, his outward circumstances had so much improved, that he could easily afford to make a home without the necessity of such a round of work as he had attempted in Vienna. 'We are young,' he writes on Feb. 19, 1840, 'and have hands, strength, and reputation; and I have a little property that brings in 500 thalers a year. The profits of the paper amount to as much again, and I shall get well paid for my compositions. Tell me now if there can be real cause for fear.' One thing alone made him pause for a time. His bride-elect was decorated with different titles of honour from the courts at which she had played in her concert-tours. He himself had, it is true, been latterly made a member of several musical societies, but that was not enough. In the beginning of 1840 he executed a scheme which he had cherished since 1838, and applied to the university of Jena for the title of Doctor of Philosophy. Several cases in which the German universities had granted the doctor's diploma to musicians had lately come under Schumann's notice; for instance the university of Leipzig had given the honorary degree to Marschner in 1835, and to Mendelssohn in 1836, and these may have suggested the idea to him. Schumann received the desired diploma on Feb. 24, 1840. As he had wished, the reason assigned for its bestowal is his well-known activity not only as a critical and æsthetic writer, but as a creative musician.[9] At last, after a year of suspense, doubts, and disagreements, the marriage of Robert Schumann with Clara Wieck took place on Sept. 12, 1840, in the church of Schönefeld, near Leipzig.

The 'Davidsbündlertanze,' previously mentioned, bore on the title-page of the first edition an old verse—

In all und jeder Zeit

Verknüpft sich Lust und Leid:

Bleibt fromm in Lust, und seyd

Beim Leid mit Muth bereit;

which may be rendered as follows:

Hand in hand we always see

Joy allied to misery:

In rejoicing pious be,

And bear your woes with bravery.

And when we observe that the two first bars of the first piece are borrowed from a composition by Clara Wieck (op. 6, no. 5), we understand the allusion. Schumann himself admits that his compositions for the piano written during the period of his courtship reveal much of his personal experience and feelings, and his creative work in 1840 is of a very striking character. Up to this time, with the exception of the Symphony in G minor, which has remained unknown, he had written only for the piano; now he suddenly threw himself into vocal composition, and the stream of his invention rushed at once into this new channel with such force that in that single year he wrote above one hundred songs. Nor was it in number alone, but in intrinsic value also, that in this department the work of this year was the most remarkable of all Schumann's life. It is not improbable that his stay in Vienna had some share in this sudden rush into song, and in opening Schumann's mind to the charms of pure melody. But still, when we look through the words of his songs, it is clear that here more than anywhere, love was the prompter—love that had endured so long a struggle, and at last attained the goal of its desires. This is confirmed by the 'Myrthen' (op. 25), which he dedicated to the lady of his choice, and the twelve songs from Rückert's 'Liebesfrühling'—Springtime of Love—(op. 37), which were written conjointly by the two lovers. 'I am now writing nothing but songs great and small,' he says to a friend on Feb. 19, 1840; 'I can hardly tell you how delightful it is to write for the voice as compared with instrumental composition, and what a stir and tumult I feel within me when I sit down to it. I have brought forth quite new things in this line.' With the close of 1840 he felt that he had worked out the vein of expression in the form of song with pianoforte accompaniment, almost to perfection. Some one expressed a hope that after such a beginning a promising future lay before him as a song-writer, but Schumann answered, 'I cannot venture to promise that I shall produce anything further in the way of songs, and I am satisfied with what I have done.' And he was right in his firm opinion as to the peculiar character of this form of music. 'In your essay on song-writing,' he says to a colleague in the 'Zeitschrift,' 'it has somewhat distressed me that you should have placed me in the second rank. I do not ask to stand in the first, but I think I have some pretensions to a place of my own.'

As far as anything human can be, the marriage was perfectly happy. Besides their genius, both husband and wife had simple domestic tastes, and were strong enough to bear the admiration of the world without becoming egotistical. They lived for one another, and for their children. He created and wrote for his wife, and in accordance with her temperament; while she looked upon it as her highest privilege to give to the world the most perfect interpretation of his works, or at least to stand as mediatrix between him and his audience, and to ward off all disturbing or injurious impressions from his sensitive soul, which day by day became more and more irritable. Now that he found perfect contentment in his domestic relations, he withdrew more than ever from intercourse with others, and devoted himself exclusively to his family and his work. The deep joy of his married life produced the direct result of a mighty advance in his artistic progress. Schumann's most beautiful works in the larger forms date almost exclusively from the years 1841—5.

In 1841 he turned his attention to the Symphony, as he had done in the previous year to the Song, and composed in this year alone, no fewer than three symphonic works. The B♭ Symphony (op. 38) was performed as early as March 31, 1841, at a concert given by Clara Schumann in the Gewandhaus at Leipzig. Mendelssohn conducted it, and performed the task with so much zeal and care as truly to delight his friend. The other two orchestral works were given at a concert on Dec. 6 of the same year, but did not meet with so much success as the former one. Schumann thought that the two together were too much at once; and they had not the advantage of Mendelssohn's able and careful direction, for he was spending that winter in Berlin. Schumann put these two works away for a time, and published the B♭ Symphony alone. The proper title of one of these was 'Symphonistische Phantasie,' but it was performed under the title of 'Second Symphony,' and, in 1851, the instrumentation having been revised and completed, was published as the 4th Symphony (D minor, op. 120). The other was brought out under an altered arrangement, which he made in 1845, with the title 'Ouverture, Scherzo, et Finale' (op. 52); and it is said that Schumann originally intended to call it 'Sinfonietta.' Beside these orchestral works the first movement of the Pianoforte Concerto in A minor was written in 1841. It was at first intended to form an independent piece with the title of 'Fantasie.' As appears from a letter of Schumann's to David, it was once rehearsed by the Gewandhaus orchestra in the winter of 1841–2. Schumann did not write the last two movements which complete the concerto until 1845.

The year 1842 was devoted to chamber music. The three string quartets deserve to be first mentioned, since the date of their composition can be fixed with the greatest certainty. Although Schumann was unused to this style of writing, he composed the quartets in about a month—a certain sign that his faculties were as clear as his imagination was rich. In the autograph,[10] after most of the movements is written the date of their completion. The Adagio of the first quartet bears the date June 21, 42; the finale was 'finished on St. John's day, June 24, 1842, in Leipzig.' In the second quartet the second movement is dated July 2, 1842, and the last July 5, 1842, Leipzig. The third is dated as follows: first movement July 18, second July 20, third July 21, and the fourth Leipzig, July 22, all of the same year. Thus the two last movements took the composer only one day each. These quartets, which are dedicated to Mendelssohn, were at once taken up by the Leipzig musicians with great interest. The praise bestowed upon them by Ferdinand David called forth a letter from Schumann, addressed to him, which merits quotation, as showing how modest and how ideal as an artist Schumann was:—'Härtel told me how very kindly you had spoken to him about my quartets, and, coming from you, it gratified me exceedingly. But I shall have to do better yet, and I feel, with each new work, as if I ought to begin all over again from the beginning.' In the beginning of October of this year the quartets were played at David's house; Hauptinann was present, and expressed his surprise at Schumann's talent, which, judging only from the earlier pianoforte works, he had fancied not nearly so great. With each new work Schumann now made more triumphant way—at all events in Leipzig. The same year witnessed the production of that work to which he chiefly owes his fame throughout Europe—the Quintet for Pianoforte and Strings (op. 44). The first public performance took place in the Gewandhaus on Jan. 8, 1843, his wife, to whom it is dedicated, taking the pianoforte part. Berlioz, who came to Leipzig in 1843, and there made Schumann's personal acquaintance, heard the quintet performed, and carried the fame of it to Paris. Besides the quintet, Schumann wrote, in 1842, the Pianoforte Quartet (op. 47) and a pianoforte Trio. The trio, however, remained unpublished for eight years, and then appeared as op. 88, under the title of 'Phantasiestücke for Pianoforte, Violin, and Violoncello.' The quartet too was laid aside for a time; it was first publicly performed on Dec. 8, 1844, by Madame Schumann, in the Gewandhaus, David of course taking the violin part, and Niels W. Gade, who was directing the Gewandhaus concerts that winter, playing the viola.

With the year 1843 came a total change of style. The first works to appear were the Variations for two pianos (op. 46), which are now so popular, and to which Mendelssohn may have done some service by introducing them to the public, in company with Madame Schumann, on Aug. 19, 1843. The principal work of the year, however, was 'Paradise and the Peri,' a grand composition for solo-voices, chorus, and orchestra, to a text adapted from Moore's 'Lalla Rookh.' The enthusiasm created by this work at its first performance (Dec. 4, 1843), conducted by the composer himself, was so great that it had to be repeated a week afterwards, on Dec. 11, and on the 23rd of the same month it was performed in the Opera House at Dresden. It will be easily believed that from this time Schumann's fame was firmly established in Germany, although it took twenty years more to make his work widely and actually popular. Having been so fortunate in his first attempt in a branch of art hitherto untried by him, he felt induced to undertake another work of the same kind, and in 1844 began writing the second of his two most important choral works, namely, the music to Goethe's 'Faust.' For some time however the work consisted only of four numbers. His uninterrupted labours had so affected his health, that in this year he was obliged for a time to forego all exertion of the kind.

The first four years of his married life were passed in profound retirement, but very rarely interrupted. In the beginning of 1842 he accompanied his wife on a concert-tour to Hamburg, where the B♭ Symphony was performed. Madame Schumann then proceeded alone to Copenhagen, while her husband returned to his quiet retreat at Leipzig. In the summer of the same year the two artists made an excursion into Bohemia, and at Königswart were presented to Prince Metternich, who invited them to Vienna. Schumann at first took some pleasure in these tours, but soon forgot it in the peace and comfort of domestic lite, and it cost his wife great trouble to induce him to make a longer journey to Russia in the beginning of 1844. Indeed she only succeeded by declaring that she would make the tour alone if he would not leave home. 'How unwilling I am to move out of my quiet round,' he wrote to a friend, 'you must not expect me to tell you. I cannot think of it without the greatest annoyance.' However, he made up his mind to it, and they started on Jan. 26. His wife gave concerts in Mitau, Riga, Petersburg and Moscow; and the enthusiasm with which she was everywhere received attracted fresh attention to Schumann's works, the constant aim of her noble endeavours. Schumann himself, when once he had parted from home, found much to enjoy in a journey which was so decidedly and even brilliantly successful. At St. Petersburg he was received with undiminished cordiality by his old friend Henselt, who had made himself a new home there. At a soirée at Prince Oldenburg's Henselt played with Madame Schumann her husband's Variations for two pianos. The B♭ Symphony was also performed under Schumann's direction at a soirée given by the Counts Joseph and Michael Wielhorsky, highly esteemed musical connoisseurs; and it is evident that the dedication of Schumann's PF. Quartet (op. 47) to a Count Wielhorsky was directly connected with this visit.