A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Scotish Music

SCOTISH MUSIC. As national music, that of Scotland has long been held in high esteem. Early notices of it may be meagre, but are always laudatory. Unfortunately, there are no means of proving what it was in remote times, for the art of conveying a knowledge of sounds by comprehensible written signs was a late invention, and music handed down by mere tradition is always most untrustworthy. Even after the invention of musical writing, the learned men who possessed the art employed it almost entirely in the perpetuation of scholastic music, having apparently an equal contempt for melody in general, and for the tunes prized by the uneducated vulgar. There is a belief that the earliest Scotish music was constructed on a series of sounds which has been styled Pentatonic, not, however, peculiar to Scotland, for airs of a similar cast have been found in countries so wide apart as China and the West Coast of Africa. Many have conceived the idea that the style was brought into this island by its earliest known inhabitants—the little dark men of the Iberian race. Others, with more or less probability, ascribe its introduction to the Celts, whose love of music is generally admitted. As no evidence is or can be offered on either side, it is sufficient to mention the conjectures.

It is a remarkable fact that the first to write a history of Scotish music based on research was an Englishman, Joseph Kitson, a celebrated antiquary and critic, who wrote towards the end of last century. He seems to have been a man of irascible temperament, but love of truth lay at the root of his onslaughts upon Johnson, Warton, Percy, Pinkerton, and others. Any assertion made without sufficient evidence, he treated as falsehood, and attacked in the most uncompromising manner. His 'Historical Essay on Scotish Song' has so smoothed the way for all later writers on the subject that it would be ungenerous not to acknowledge the storehouse from which his successors have drawn their information—in many cases without citing their authority. The early portion of the Essay treats of the poetry of the songs, beginning with mere rhymes on the subject of the death of Alexander III. (1285), the siege of Berwick (1296), Bannockburn (1314), and so on to the times of James I. (1393–1437), whose thorough English education led to his being both a poet and a musician. His 'truly excellent composition At Beltayne or Peblis to the play is still held in high esteem,' but of his music there are no remains. This is the more to be regretted as a well-worn quotation from Tassoni states that 'Non pur cose sacre compose in canto, ma trovò da se stesso una nuova musica lamentevole e mesta, differente da tutte l'altre'—James (first) King of Scotland not only wrote sacred compositions for the voice, but found out of himself a new style of music, plaintive and mournful, differing from every other.' This description of 'plaintive and mournful' agrees very well with one style of Scotish music; and as the King wrote poetry to please his unlettered subjects he may also occasionally have composed music of an equally popular cast. That James improved Scotish music need not be doubted, but it is altogether absurd to suppose that he invented a style that must have been in existence long before his era. The quotation, however, serves to show that in Italy James and not Rizzio—most gratuitously supposed to have aided the development of Scotish music—was believed to have originated or amended this style. As Tassoni flourished soon after Kizzio's time, he had an opportunity of knowing somewhat more of the question than writers who came a century and a half later. George Farquhar Graham has at some length controverted the Rizzio myth. Graham was a very competent judge of such matters, and believed that some of our airs might be of the 15th century; though the earliest to which a date can now be affixed is the 'Lament for Flodden,' 1513, of which further mention will be made.

As so little is known of the popular music of the 15th century, a few extracts from the accounts of the Lords High Treasurers of Scotland may be found interesting. They show the value placed on the services of musicians who at various times visited the Courts of James III. and James IV. Scotish money being usually reckoned as worth only one twelfth of English money, the payments seem very small; but are not so in reality. For on consulting a table of prices of provisions supplied for a banquet given by James IV. to the French ambassador, it is found that a gratuity such as that to John Broun would buy seven oxen; and that the 'twa fithelaris' (fiddlers) who sang 'Graysteil' to the King received the value of three sheep. The sums seem odd, but an examination of the items will show that the payments were made in gold. The unicorn (a Scottish coin that weighed from 57 to 60 grains of gold) is valued in the accounts at eighteen shillings; and another coin, the equivalent of the French crown, at fourteen shillings—

Mr. Gunn, in his Enquiry on the Harp in the Highlands, quotes thus from a work of 1597—'The strings of their Clairschoes (small Gaelic harp) are made of brasse wyar, and the strings of the Harp of sinews, which strings they stryke either with their nayles growing long or else with an instrument appointed for that use.' The correct word is Clarsach; and the harper Clarsair.

(Which means that the thriftless Jacob received the value of eleven sheep to redeem his lute that lay in pawn.)

(Riotous fellows, no doubt, who got a French crown each to clear their 'score' in Edinburgh, and hire horses to Linlithgow.)

Information regarding the state of popular music during the 16th century is almost equally meagre. James V. is believed to have written two songs on the subject of certain adventures which befell him while wandering through the country in disguise; these are 'The gaberlunzie man' and 'The beggar's mealpokes' (mealbags). The airs are said to be of the same date, but of this there is really no certainty; though Ritson, with all his scepticism, admits them into his list of early tunes; the second is much too modern in style to have been of James V's date. Of Mary's time there are two curious works in which musical matters are mentioned. 'The Complaynte of Scotland' (1549), and 'The Gude and Godly Ballates' (ballads) (1578), both of which furnish the names of a number of tunes almost all now unknown. Mr. J. A. H. Murray, in his excellent reprint of the former of these, says 'The Complaynte of Scotland consists of two principal parts, viz. the author's Discourse concerning the affliction and misery of his country, and his Dream of Dame Scotia and her complaint against her three sons. These are, with rather obvious art, connected together by what the author terms his Monologue Recreative.'

This Monologue—which, from its being printed on unpaged leaves, Mr. Murray has discovered to be an afterthought—is now the most interesting part of the work. In it the author introduces a number of shepherds and their wives. After 'disjune' (déjeuner) the chief shepherd delivers a most learned address, and then they proceed to relate stories from ancient mythology, and also from the middle ages. Short extracts to give an idea of the style may not be objected to.

Quhen the scheipherd hed endit his prolixt orison to the laif of the scheiphirdis, i meruellit nocht litil quhen i herd ane rustic pastour of bestialite, distitut of vrbanite, and of speculations of natural philosophe, indoctryne his nychtbours as he hed studeit ptholome, auerois, aristotel, galien, ypocrites or Cicero, quhilk var expert practicians in methamatic art.… Quhen thir scheipliyrdis hed tald al thyr pleysand storeis, than thay and ther vyuis began to sing sueit melodius sangisof natural music of the antiquite. the foure marmadyns that sang quhen thetis vas mareit on month pillion, thai sang nocht sa sueit as did thir scheiphyrdis.…

Then follows a list of songs, including—

Pastance vitht gude companye, Stil vndir the leyuis grene, Cou thou me the raschis grene, … brume brume on hil, … bille vil thou cum by a lute and belt the in Sanct Francis cord, The frog cam to the myl dur, rycht soirly musing in my mynde, god sen the due hed byddin in France, and delaubaute hed neuyr cum hame, … o lusty maye vitht flora quene, … the battel of the hayrlau, the hunttis of cheuet, … My lufe is lyand seik, send hym ioy, send hym ioy, … The perssee and the mongumrye met, That day, that day, that gentil day.

With the exception of the ballads, these seem to be chiefly part-songs, some of them English.

Than eftir this sueit celest armonye, tha began to dance in ane ring, euyrie ald scheiphyrd led his vyfe be the hand, and euyrie ȝong scheiphird led hyr quhome he luffit best. Ther vas viij scheipnyrdis, and ilk ane of them hed ane syndry instrament to play to the laif. the fyrst hed ane drone bag pipe, the nyxt hed ane pipe maid of ane bleddir and of ane reid, the thrid playit on ane trump, the feyrd on ane corne pipe, the fyft playit on ane pipe maid of ane gait home, the sext playt on ane recordar, the seuint plait on ane fiddil, and the last plait on ane quhissil.

The second instrument seems to have been a bagpipe without the drone; the third, a jew's-harp, and the last a shepherd's-pipe, or flute à bec. Sir J. Graham Dalyelt says 'Neither the form nor the use of the whistle (quhissil) is explicit. It is nowhere specially defined. In 1498 xiiij s. is paid for a whussel to the King.… Corn-pipe, Lilt-pipe, and others are alike obscure.'

In the other little book already mentioned, known as the 'Gude and Godly Ballates' (1578) there are a number of songs 'converted from profane into religious poetry.' Dr. David Laing, who published a reprint of it in 1868, informs us that the authorship of the work is usually assigned to two brothers, John and Robert Wedderburn of Dundee, who flourished about the year 1540. It is divided into three portions; the first is doctrinal; the second contains metrical versions of Psalms, with some hymns, chiefly from the German; the third, which gives its peculiar character to the collection, may be described as sacred parodies of secular songs. They were to be sung to well-known melodies of the time, which were indicated usually by the first line or the chorus; but as Dr. Laing points out that not one of the secular songs of which these parodies were imitations has come down to us, a few only of the tunes can be ascertained. Three of them are certainly English, 'John cum kiss me now,' 'Under the greenwood tree,' and 'The huntis up.' A fourth is 'Hey now the day dawes,' which Sibbald and Stenhouse have attempted to identify with 'Hey tuti taiti' (Scots wha hae). This is not only improbable, but is disproved by a tune of the same name being found in the Straloch MS. (1627). It has no Scotish characteristics, and may have been picked up from some of the English or foreign musicians who were frequent visitors at the Scotish Court. It is an excellent lively tune, and may have been that played by the town pipers of Edinburgh in the time of James IV; if so, the note marked with an asterisk must have been altered to C to suit the scale of the instrument. Dunbar thought it so hackneyed that he complains

Your common menstrallis has no tone

But 'Now the day dawis' and 'Into Joun'

Think ye nocht shame.

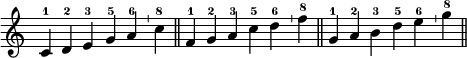

The day dawis.

(From the Straloch MS. a.d. 1627.)

Of the other songs, 'Ah my love, leif me not' may be 'I'll never leave thee,' and 'Ane sang on the birth of Christ, to be sung with the tune of Bawlulalu,' may probably be 'Baloo my boy lie still and sleep,' for in both songs the measure and also the subject—sacred for secular—are the same. The words, being in Bishop Percy's ancient MS., are thought to be English, but Dr. Rimbault considered the tune to be Scotish. Sibbald's identifications of a few other tunes are altogether fanciful: 'The wind blaws cauld, furious and bauld,' with 'Up in the morning early'; 'My luve murnis for me,' with 'He's low down in the broom,' and so on. Altogether not more than a third of the whole can now be even guessed at.

The religious troubles of this and the following reigns would no doubt completely unsettle whatever musical tuition might be carried on by the Romish Church, but the introduction of 'sang schuils' and of Genevan Psalmody would probably soon compensate for any loss thence arising. [Sang Schools.] It does not come within the scope of this paper to consider such changes; but the allegation already alluded to, that Rizzio composed some of the finest Scotish melodies, is deserving of a more careful enquiry.

Goldsmith, at the instigation apparently of Geminiani, chose to write an essay on a subject of which he evidently knew very little. He asserts that Rizzio was brought over from Italy by James V., lived twenty years in Scotland, and thus had sufficient time to get a knowledge of the style, and ample opportunities for improving it. It is well known, on the contrary, that Rizzio came over in the suite of the Piedmontese Ambassador in 1561, 19 years after the death of James V., and was little more than four years in Scotland. That he ever composed anything in any style has yet to be shown. Tassoni, who was born the year of Rizzio's death (1565), and who speaks of Scotish music—as has already been noticed—entirely ignores him. In truth the myth seems to have been got up in London early in the last century, probably among his own countrymen. It is first heard of in the 'Orpheus Caledonius' of 1725, where the editor ascribes seven tunes to him. Two at least of these are shown by their style to be very recent compositions; but the absurdity of the statement must have been quite apparent, as all mention of Rizzio's name was withdrawn in the next edition of the work, 1733.

Oswald, by jestingly ascribing some of his own compositions to Rizzio, helped to keep up the falsehood. Notwithstanding the disclaimers of Ritson, Hawkins, and more recently of G. Farquhar Graham, as well as of all who have made any research into the question, the belief still exists, and is from time to time gravely propounded by persons who ought to know better, For 160 years after his death Rizzio is not mentioned as having composed music of any kind. Had he done so, it would have been in the style of France or of Italy, and it may be doubted whether Queen Mary herself would have appreciated any other. It must not be forgotten that she quitted Scotland when little more than five years of age, and returned Queen Dowager of France, a widow of nineteen, with all her tastes formed and every association and recollection connected with a more civilised country than her own.

Mr. Dauney, in his Dissertation prefixed to the Skene MS. gives some interesting information regarding the Chapel Royal in Stirling. It was founded by James III., of whom Lindsay of Pitscottie says that 'he delighted more in musick and in policies of Bigging (building) than he did in the governance of his realm … He delighted more in singing and playing on instruments, than he did in the Defence of the Borders … He took great pleasour to dwell thair (in Stirling) and foundet ane collige within the said Castle callit the Chappell Royal; also he bigget the great hall of Stirling; also he maid in the said Chappell Royal all kynd of office men, to wit, the bishop of Galloway archdean, the treasurer and sub-dean, the chantor and sub-chantor, with all other officieris pertaining to a College; and also he doubled thaim, to that effect, that, they schould ever be readie; the one half to pass with him wherever he pleased, that they might sing and play to him and hold him merrie; and the other half should remain at home to sing and pray for him and his successioun' (ed. 1728). All this was afterwards abolished; but in 1612 its restoration was ordered by James VI., its place of residence to be at 'Halyrudhous'—'the palace of the sumyn, and the Chappell not to be called the Chappell royall of Striveling as heretofore but his majesties Chappell Royall of Scotland, and the members to attend his majesty in whatever part of Scotland he may happen to be.' In 1629 Charles I. granted an annual pension of 2000 to the musicians of the Chapel, and preparations were made for the celebration of religious service according to the forms of the Church of England. The nature of these arrangements is very fully given in an 'Information to the King by E. Kellie' (1631): among other things he was appointed 'to see that none but properly qualified persons should have a place there, and that they should all be kept at daily practise, and for that effect your Majestie appointed mee ane chambre within your pallace of Halyrudhous wherein I have provided and sett up, ane organe, two flutes, two pandores, with violls and other instruments, with all sorts of English, French, Dutch, Spaynish, Latine, Italian, and Old Scotch music, vocall and instrumentall.' The capitals are Mr. Dauney's, who says, 'There can be no doubt that this last expression referred to the popular national music of Scotland. That sacred music was here not meant is sufficiently obvious; the metrical psalmody of the Reformed Church was not old, and the music of the Church in Scotland before the Reformation was identical with that of Rome, and therefore not Scottish.' Here Mr. Dauney surely applies to the music what can only be said of the words of the service; the latter were the same throughout all Roman Catholic countries, while the music, on the contrary, varied in every locality, being frequently the composition of the chapel-master or of the organist of the church where it was performed. Without insisting on the fact already stated, that James I. of Scotland wrote sacred music—'cose sacre compose in canto'—reference may be made to the Scotish composers mentioned by Dr. David Laing as having written music for the church before the Reformation. Among these are Andrew Blackhall, a canon of Holyrood; David Peblis, one of the canons of St. Andrews, who in 1530 set the canticle 'Si quis diliget me' in five parts; and Sir John Futhy ('the Sir denotes he was a priest'), who wrote a moral song, 'God abufe,' in four parts, 'baith letter and not,' that is, both words and music—as well as others whose names it is unnecessary to mention. Besides, there need not be a doubt that their predecessors were occasional composers from the time when James I. in 1424 set up organs in churches. That this is the music called Old Scotish in Kellie's 'Information' seems to be the only reasonable explanation of these words. For though the members of Kellie's choir in fitting time and place might sing to the king 'to hold him merrie,' this would not be the music which they were called upon to practise twice a week in preparation for the next service.

It is to the reign of Charles I. that we owe the first certain glimpse of early Scotish folk-music. All that was known of it had come down by tradiion, till the discovery—only in the present century—of two MSS. of this date, which establish the existence of a number of tunes whose age and form were previously entirely conjectural. These are the Straloch and Skene MSS. The first was written by Robert Gordon of Straloch, Aberdeenshire, in 1627–29. It was presented to Dr. Burney in 1781, but the present possessor is not known. Fortunately it was in 1839 submitted to G. Farquhar Graham, who, by permission, made an excerpt from it of all that was worthy of preservation, and presented this to the Advocates' Library. The copy was of course exact, and contained all the errors of the original, which were numerous: these make a translation from the Lute Tablature—in which it is written—into the usual notation a very arduous task, requiring much patience, knowledge, and ingenuity.

The second is a much more important MS. It was formed by or for John Skene of Hallyards, Midlothian, and has no date; but its seven parts, now bound together, seem from internal evidence to have been written at various times up to about 1635. In general it is much more correct than the last, its versions are occasionally excellent; its Scotish airs, after rejecting dances and everything else not of home growth, are not fewer than forty. Above all, it contains the ancient original melody of 'The flowers of the forest'; whose simple pathos forbids our believing it to be the expression of any but a true sorrow, the wail of a mourner for those who would never return—and which no doubt is nearly coeval with Flodden. The MS. was published in 1838 by Mr. Wm. Dauney, with a Dissertation, excellent in many respects, on the subject of Scotish music. He was greatly assisted by G. Farquhar Graham, who not only translated the MS. from Lute Tablature, but contributed much musical and other information. In order to give some idea of the style of writing in Tablature a woodcut of a small portion of the MS. is inserted.

As these MSS. had not been discovered in Ritson's time, it does not surprise one to find him saying in his letters (1791) that 'the Scotish airs that could be satisfactorily proved to have existed earlier than the Restoration are in all only twenty-four.' If from these are deducted all that do not fall under the head of folk-music, then his estimate must be reduced by nearly a half, for he included part-songs such as 'O lusty May'; several tunes now known to be English; and, notwithstanding his noted scepticism, even the air which, for want of an earlier name, is called 'Hei tuti taiti'; appending this note however—'said, without the slightest probability, to have been King Robert Bruce's march to Bannockburn' These MSS. enlarge this estimate considerably. Leaving out the English airs and foreign dances, upwards of fifty tunes must be added to it. Some of them are in a rather rudimentary state, but distinctive traits serve to identify them with certain known tunes. The versions of others are simple and beautiful, often greatly preferable to those of the same airs handed down traditionally. Although the number of melodies that can thus be traced in the 17th century is still comparatively small, yet it must be evident to all who have studied the subject, that a much larger number, then in existence, did not appear either in print or in manuscript tilt the following century. Not till then do we find 'Aye waukin O,' 'Waly waly,' 'Barbara Allan,' 'Ca the yowes,' 'Gala water,' 'I had a horse,' and many others equally old. Ramsay and Thomson (1725) omitted these and similar simple airs from their collections, while florid tunes such as 'John Hay's bonnie lassie' and 'Love is the cause of my mourning' abound in their volumes The taste of their times was for ornament, in ours it is for simplicity; indeed the very simplicity which we prize they seem to have despised.

The extreme rarity of MSS. such as those mentioned is greatly to be regretted. The never-ceasing wars upon the borders, and the private feuds throughout the rest of the kingdom, with their consequent destruction of castles and keeps, abbeys and cathedrals, have had much to do with the sweeping away of musical records of ancient date which would otherwise have come down to us

From some anecdotes told of Charles II. he seems to have had a great liking for Scotish music, and certainly from the Restoration it became popular in England. This is shown by the almost innumerable imitations of the style that are to be found in the various publications of John Playford. They are usually simply called 'Scotch tunes,' but sometimes the name of the composer is given, showing that no idea of strict nationality attached to them. In general they are worthless; but occasionally excellent melodies appear among them, such as 'She rose and let me in,' 'Over the hills and far away,' 'De'il take the wars,' 'Sawney was tall' (Corn rigs), 'In January last' (Jock of Hazeldean), all of which, with many others of less note, have been incorporated in Scotish Collections, at first from ignorance, afterwards from custom, and without further enquiry. There are however many tunes, not to be confounded with these, which two or even three centuries ago were common to the northern counties of England and the adjoining counties of Scotland, the exact birthplace of which will never be satisfactorily determined; for we agree with Mr. H. F. Chorley in believing that the first record in print does not necessarily decide the parentage of a tune.

Among these—though rather on account of the words than the music—may be classed the famous song 'Tak your auld cloak about ye,' which having been found in Bishop Percy's Ancient MS. has been claimed as entirely English. The Rev. J. W. Ebsworth, a very high authority, believes it to be the common property of the Border counties of both nations. Probably it is so; yet it seems strange that so excellent a ballad, if ever popularly known in England, should have so utterly disappeared from that country as not to be even mentioned in any English work, or by any English author with the exception of Shakspere, who has quoted one stanza of it in Othello. Not a line of it is to be found in the numerous 'Drolleries' of the Restoration, in the publications of Playford and D'Urfey, or in the 'Merry Musicians' and other song-books of the reign of Queen Anne. Even the printers whose presses sent forth the thousands of blackletter ballads that fill the Roxburgh, Pepys, Bagford and other Collections, ignore it entirely. Allan Ramsay, in 1728, was the first to print it, nearly forty years before Bishop Percy gave his version to the world, confessing to have corrected his own by copies received from Scotland. The question naturally arises, where did Allan Ramsay get his copy of the ballad, if not from the singing of the people. Certainly not from England, for there it was then unknown.

The ancient Percy MS. contains, however, several excellent stanzas not found elsewhere, as well as some others that by the total absence of sense as well as of rhymes show they are corrupt. In the last stanza the transcriber of the MS. has given the sound rather than the sense, as conveyed by the words of the Scotish Version. These are

Nocht's to be won at woman's han'

Unless you gie her a' the plea;

Sae I'll leave aff where I began

And tak my auld cloak about me.

'To give one all the plea,' is a common Scotish phrase for giving up the whole subject that is in debate. The Percy MS. says

It's not for a man with a woman to threape

Unless he first give over the play:

We will live now as we began

And I'll have myne old cloak about me.

A critical comparison in detail of the two versions would be out of place here, but it will well repay the trouble, and reveal many small points of difference in the national character of the two countries.

The half century after the Revolution was a busy one both with Jacobite poetry and music; of the former the quantity is so great as to require a volume of its own. In regard to the music, little, if any of it, was new, for the writers of the words had the wisdom to adapt their verses to melodies that every one knew and could sing. Thus many old favourite tunes got new names, while others equally old have perhaps been saved to us by their Jacobite words, their early names being entirely lost. The story of the battle of Killiecrankie 1689 is one of the earliest of these songs, and enjoys the distinction of having a Latin translation, beginning

Grahamius notabilis coegerat Montanos

Qui clypeis et gladiis fugarunt Anglicanos,

Fugerant Vallicolae atque Puritani

Cacavere Batavi et Cameroniani.

It is sung to a Gaelic tune of its own name, so quickly and so widely spread as to be found in a Northumbrian MS. of 1694, as the Irish Gillicranky. It is a stirring bagpipe tune, no doubt older than the words.

A still more celebrated air, now known as 'Scots wha hae,' received its name of 'Hey tuti taiti' from a stanza of a song of 1716 (?), 'Here's to the king, sir; Ye ken wha I mean, sir.' The stanza is worth quoting, and would be yet more so could it tell us the still earlier name of the tune, a subject which has caused much discussion.

When you hear the trumpet soun'

Tuti taiti to the drum,

Up sword, and down gun,

And to the loons again.

The words 'Tuti taiti' are evidently only an attempted imitation of the trumpet notes, and not the name of the air. To suppose that the tune itself was played on the trumpet as a battle call is too absurd for consideration. As the air has a good deal in common with 'My dearie, an thou dee,' there seems considerable probability that it was another version of the same, or that the one gave rise to the other, a thing likely enough to happen in days when there being no books to refer to, one singer took his tune as he best could from his neighbour.

'When the king comes owre the water'—otherwise 'Boyne water'—is a good example of change of name; the air has recently been discovered in a MS. of 1694, where it is called 'Playing amang the rashes,' a line of an old Scotish song recovered by Allan Ramsay, and printed in his 'Tea Table Miscellany' 1724—a fact which seems somewhat to invalidate the Irish claim to the tune.

When the king comes owre the water,

(Playing amang the rashes.)

From W. Graham's Flute Book (MS. 1694).

The Jacobite words are said to have been written by Lady Keith Marischall, mother of the celebrated Marshal Keith, a favourite general of Frederic the Great.

The old air, already mentioned, 'My dearie, an thou dee,' may be pointed out as the tune of an excellent Jacobite song 'Awa, Whigs, awa,' and of another—the name of which is all that has come down to us—'We're a' Mar's men,' evidently alluding to the Earl of Mar, generalissimo of James's forces in Scotland in 1715.

Another of the songs of 1715, 'The piper o' Dundee,' gives the names of a number of tunes supposed to be played by the piper—Carnegie of Finhaven—to stir up the chiefs and their clans to join the Earl of Mar.

He play'd the 'Welcome o'er the main,'

And 'Ye'se be fou and I'se be fain,'

And 'Auld Stuarts back again,'

Wi' meikle mirth and glee.

He play'd 'The Kirk,' he play'd 'The Quier,' [choir]

'The Mullin dhu' and 'Chevalier,'

And 'Lang away but welcome here,'

Sae sweet, sue bonnilie.

Notwithstanding the diligence of collectors and annotators some of these songs and tunes have eluded recognition, chiefly because of a habit of those times to name a tune by any line of a song—not necessarily the first—or by some casual phrase or allusion that occurred in it.

Other noted songs of this date are 'Carle an (if) the King come'; 'To daunton me'; 'Little wat ye wha's comin,' the muster-roll of the clans; 'Will ye go to Sheriffmuir'; and 'Kenmure's on and awa.'

A striking phase of Jacobite song was unsparing abuse of the House of Hanover; good specimens of it are 'The wee wee German lairdie,' 'The sow's tail to Geordie,' and above all, 'Cumberland's descent into hell,' which is so ludicrous and yet so horrible that the rising laugh is checked by a shudder. This however belongs to the '45, the second rising of the clans. Of the same date is 'Johnie Cope,' perhaps the best- known of all the songs on the subject. It is said to have been written immediately after the battle of Prestonpans, by Adam Skirving, the father of a Scottish artist of some reputation. No song perhaps has so many versions; Hogg says it was the boast of some rustic singer that he knew and could sing all its 19 variations. Whether it was really Skirving's or not, he certainly did write a rhyming account of the battle, in 15 double stanzas relating the incidents of the fight—who fled and who stayed—winding up with his own experiences.

That afternoon when a' was done

I gaed to see the fray, man,

But had I wist what after past,

I'd better staid away, man:

On Seton sands, wi' nimble hands,

They pick'd my pockets bare, man;

But I wish ne'er to drie sic fear,

For a' the sum and mair, man.

Few of these old songs are now generally known; the so-called Jacobite songs, the favourites of our time, being almost entirely modern. Lady Nairne, James Hogg, Allan Cunningham, Sir Walter Scott, may be named as the authors of the greater portion of them. In most cases the tunes also are modern. 'Bonnie Prince Charlie' and 'The lament of Flora Macdonald' are both compositions of Neil Gow, the grandson of old Neil the famous reel-player—'He's owre the hills that I loe weel,' 'Come o'er the stream, Charlie,' 'The bonnets of bonnie Dundee' (Claverhouse), are all of recent origin; even 'Charlie is my darling'—words and music—is a modern rifacimento of the old song.

Charlie is my darling. The Old Air.

The Modern Air.

One exception to this ought to be noted; the tune now known as 'Wae 's me for Prince Charlie' is really ancient. In the Skene MS. (1635) it is called 'Lady Cassilis' Lilt'; it is also known as 'Johnny Faa,' and 'The Gypsy laddie,' all three names connected with what is now believed to be a malicious ballad written against an exemplary wife in order to annoy her Covenanting husband, the Earl of Cassilis, who was not a favourite.

Enough has been said of these relics of an enthusiastic time, but the subject is so extensive that it is not easy to be concise. Those who wish to know more of it will find in the volumes of James Hogg and Dr. Charles Mackay all that is worthy of being remembered of this episode of Scotish song.

Of the Scottish Scales and Closes.

The existence of Scotish airs constructed on the series 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 of a major diatonic scale is well known and has been already alluded to. Whether this pentatonic series was acquired through the use of a defective instrument, or from the melodic taste of singer or player, must remain mere matter of conjecture. The style itself may be accepted as undoubtedly ancient, whatever uncertainty there may be as to the exact age of the airs constructed on it. These are not by any means numerous, though their characteristic leap between the third and fifth, and sixth and eighth of the scale, is so common in Scotish melody, that many persons not only believe the greater part of our airs to be pentatonic, but do not admit any others to be Scotish. However the taste for this style may have arisen, the series of notes was a very convenient one; for an instrument possessing the major diatonic scale in one key only, could play these airs correctly in the three positions of the scale where major thirds are found, that is, on the first, fourth and fifth degrees. In the key of C, these are as shown below, adding the octave to the lowest note of the series in each case.

Pentatonic scale in three positions, without change of signature.

It would not be quite correct to term these the keys of C, F, and G, for they want the characteristic notes of each scale; still it is convenient to do so, especially as in harmonising tunes written in this series it is frequently necessary to use the omitted intervals, the fourth and seventh, and also to affix the proper signature of the key as usual at the beginning. If, reversing the order of the notes given above, we begin with the sixth, and passing downwards add the octave below, the feeling of a minor key is established, and keys of A, D and E minor seem to be produced. Besides tunes in these six keys, a few others will be found, which begin and end in G minor (signature two flats), though also played with natural notes; for B and E being avoided in the melody neither of the flats is required.

A curious peculiarity of tunes written in this series is, that from the proximity of the second and third positions phrases move up and down from one into the other, thus appearing to be alternately in the adjoining keys a full tone apart, moving for example from G into F and vice versa.

The following are good examples of the style.

(1) Gala Water.

(2) Were na my heart licht I wad die.

(3) The bridegroom grat.

![{ \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \time 4/4 \partial 4 \relative e' { \autoBeamOff

e8 g | a c a g e4 d8 c | d8.[ c16] d8[ e] a4 e8[ g] | %eol 1

a[ c] a[ g] e4 d8[ c] | d8.[ c16] d8[ e] c'4. d8 |

e[ d] c a g4 e'8 d | %eol 2

c[ a] g e d4 e8[ g] | a[ c] a[ g] e4 c'8[ d] |

e4. e,8 e4 \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { When the sheep are in the fauld and the kye at hame, And a' the world to sleep are gaine. The waes o' my heart fa' in show'rs frae my e'e, While my gude -- man lies sound by me } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/d/5dtz0vomjqpwhkly5bdm6imqxtney97/5dtz0vom.png)

The first, 'Gala Water,' is one of the most beautiful of our melodies. The modern version of it contains the seventh of the scale more than once, but Oswald has preserved the old pentatonic version in his Caledonian Pocket Companion (1759–65). That version is here given in the large type, the small type showing the modern alterations. The air may be played correctly beginning on E, on A, or on B, representing the third of the keys of C, F and G; but neither flat nor sharp is required in any of the positions, the notes being all natural throughout.

The second is the melody to which Lady Grizel Baillie wrote (1692) her beautiful ballad, 'Were na my heart licht, I would die.' It is a very simple unpretending tune, and is given chiefly on account of its close; indeed, both of these tunes are peculiar, and will again be more fully referred to.

The third is the old tune which was so great a favourite with Lady Anne Lyndsay that she wrote for it her celebrated ballad 'Auld Robin Gray.' Although it has been superseded by a very beautiful modern English air, it ought not to be entirely forgotten.

Anotherexceedingly beautiful pentatonic melody is that to which Burns wrote 'O meikle thinks my love o' my beauty.' It will be found in E minor in the 'Select Songs of Scotland,' by Professor Macfarren—no worthier arranger of our melodies could be named—but it may also be played in D minor and A minor, in each case without either flat or sharp being required in the melody.

To recapitulate. All tunes in this style, if treated as mere melodies, can be written as if in the key of C, without either flat or sharp; although if harmonised, or accompanied, the same notes may require the signature of one sharp or one flat. There are also a few tunes which even require that of two flats, although none of the characteristic notes of these scales appear in the melody. The style in its simplest form, as in 'Were na my heart licht,' is somewhat monotonous, and considerable skill is often shown in the intermingling of major and minor phrases, not merely by means of the related keys, but by transitions peculiar to the old tonality.

The use of this imperfect Pentatonic scale in our early music must gradually have ceased, through acquaintance with the music of the church service, which had a completed diatonic scale, though with a considerable want of a defined key-note. Without going into any intricacies, the church tones may, for our present purpose, be accepted as in the scale of C major, untrammeled by any consideration of a key-note, free to begin and end in any part of the scale according to circumstances; the sounds remaining the same wherever the scale might begin or end. This completed scale, which we find in the simple Shepherd's Pipe or Recorder, is really that on which our older melodies are formed. The pitch note might be D or G, or any other, but the scale would be the ordinary major diatonic, with the semitones between the 3rd and 4th and 7th and 8th degrees. The key of C is that adopted in the following remarks. With scarcely an exception the old tunes keep steadily to this scale without the use of any accidental. It will also be seen that the pathos produced by means of the 4th of the key, is a clever adaptation of a necessity of the scale. 'The Flowers of the Forest'—fortunately preserved in the Skene MS.—is a fine example of the skill with which the unskilled composer used the meagre means at his disposal. The first strain of the air is in G major, as will be seen if it be harmonised, though no F sharp was possible on the instrument; in the second strain, no more affecting wail for the disaster of Flodden could have been produced than that effected by the use of the F♮ the 4th of the scale of the instrument, the minor 7th of the original key. With his simple pipe the composer has thus given the effect of two keys.

The Flowers of the Forest. Ancient Version.

![{ \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \time 4/4 \relative g' {

g4 g8 g a[ b] d e | d b a[ g] e4 d | g g8 g a[ b] d e | %eol 1

d[ b] a8. g16 g2 \bar "||" d8[ e] f_"*" f e[ f] g8. g16 |

d8 d b'[ a] g e d4 %eol 2

d4 e8 g e'4 d8 b | a4 a8 b16 a g2 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/q/5/q5xw3q8af285f44tkfvmy3lb4o2vc1k/q5xw3q8a.png)

It may be objected that the voice was not tied down to the notes of an imperfect instrument, and could take semitones wherever it felt them to be wanted; but we must not forget that in those days our modern scales were unknown unless to scientific musicians, and that the voice, like the instrument, kept to the old tonality, the only scale which it knew.

The same effect of playing in two keys occurs in 'O waly waly! love is bonnie, a little while when it is new,' but in most modern versions of the melody both the F♮ and F♯ are found; this was not possible on the primitive instrument, though easy on the lute or violin.

O waly waly.

Any air which has the natural as well as the altered note may be set down as either modern, or as having been tampered with in modern times. The major seventh in a minor key is also a sure sign of modern writing or modern meddling, though it cannot be denied that the natural note, the minor seventh, sounds somewhat barbarous to the unaccustomed ear—and yet grand effects are produced by means of it. In a tune written otherwise in the old tonality, the occurrence of the major seventh sounds weak and effeminate when compared with the robust grandeur of the full tone below.

A few more examples may be given to show the mingling of the pentatonic with the completed scale. 'Adieu Dundee'—also found in the Skene MS.—is an example of a tune written as if in the natural key, and yet really in a modified G minor.

Adew Dundee.

Of course in harmonising the tune it would be necessary to write it in two flats; but in the melody the B is entirely avoided and the E♮ in the 15th bar is used to modulate into D minor, thus skilfully making a note available which belonged to the scale of the instrument though not to that of the tune. Another example is 'The wauking of the fauld,' which, played in the same key (G minor), has the same peculiarity in the 13th bar; this however is the case only in modern versions of the air, for that given by Allan Ramsay in the 'Gentle Shepherd' (1736) is without the E.

The closes of Scotish tunes are often so singular that a notice of their peculiarities ought not to be omitted. The explanation of the fact that almost every note of the scale is found in use as a close, is really not difficult, if the circumstances are taken into consideration. In the olden time, many of the tunes were sung continuously to almost interminable ballads, a full close at the end of every quatrain was therefore not wanted. While the story was incomplete the old minstrel no doubt felt that the music should in like manner show that there was more to follow, and intentionally finished his stanza with a phrase not to be regarded as a close, but rather as a preparation for beginning the following one; though when he really reached the end he may possibly have concluded with the key-note.

The little tune 'Were na my heart licht' [p. 444b] is an excellent example of what has just been said. It consists of four rhythms of two bars each; a modern would have changed the places of the third and fourth rhythms, and finished with the key-note, but the old singer intentionally avoids this, and ends with the second of the scale, a half close on the chord of the dominant.

Endings on the second or seventh of the scale are really only half closes on intervals of the dominant chord, the fifth of the key. Endings on the third and fifth again are half closes on intervals of the tonic chord or key-note, while those on the sixth are usually to be considered as on the relative minor; and occasionally the third may be treated as the fifth of the same chord. To finish in so unusual a manner has been called inexplicable, and unsatisfactory to the ear, whereas viewed as mere specimens of different forms of Da Capo these endings become quite intelligible, the object aimed at being a return to the beginning and not a real close.

Of the Gaelic Music.

If the difficulty of estimating the age of the music of the Lowlands is great, it is as nothing compared to what is met with in considering that of the Highlands.

When a Gael speaks of an ancient air he seems to measure its age not by centuries; he carries us back to pre-historic times for its composition. The Celts certainly had music even in the most remote ages, but as their airs had been handed down for so many generations solely by tradition, it may be doubted whether this music bore any striking resemblance to the airs collected between 1760 and 1780 by the Rev. Patrick McDonald and his brother. That he was well fitted for the task he had set himself is borne out by the following extract from a letter addressed to the present writer in 1849 by that excellent water-colourist Kenneth Macleay, R.S.A. He says, 'My grandfather, Patrick Macdonald, minister of Kilmore and Kilbride in Argyllshire who died in 1824 in the 97th year of his age was a very admirable performer on the violin, often played at the concerts of the St. Cecilia Society in Edinburgh last century, and was the first who published a collection of Highland airs. These were not only collected but also arranged by himself.' In the introduction to the work there are many excellent observations regarding the style and age of the tunes. The specimens given of the most ancient music are interesting only in so far as they show the kind of recitative to which ancient poems were chanted, for they have little claim to notice as melodies. The example here given is said to be 'Ossian's soliloquy on the death of all his contemporary heroes.'

There are however many beautiful airs in the collection; they are simple, wild, and irregular; but before their beauty can be perceived they must be sung or hummed over again and again. Of the style of performance the editor says:

'These airs are sung by the natives in a wild, artless, and irregular manner. Chiefly occupied with the sentiment and expression of the music, they dwell upon the long and pathetic notes, while they hurry over the inferior and connecting notes, in such a manner as to render it exceedingly difficult for a hearer to trace the measure of them. They themselves while singing them seem to have little or no impression of measure.'

This is more particularly the case with the very old melodies, which wander about without any attempt at rhythm, or making one part answer to another. The following air is an excellent example of the style:—

Wet is the night and cold.

In contrast to these are the Liuneags, short snatches of melody 'sung by the women, not only at their diversions but also during almost every kind of work where more than one person is employed, as milking cows and watching the folds, fulling of cloth, grinding of grain with the quern, or hand-mill, haymaking, and cutting down corn. The men too have iorrums or songs for rowing, to which they keep time with their oars.' Mr. T. Pattison (Gaelic Bards), tells us that this word Jorram (pronounced yirram), means not only a boat-song but also a lament, and that it acquired this double meaning from the Jorram being often 'chanted in the boats that carried the remains of chiefs and nobles over the Western seas to Iona.'

Patrick Macdonald says 'the very simplicity of the music is a pledge of its originality and antiquity.' Judged by this criticism his versions of the airs seem much more authentic than those of his successors. Captain Fraser of Knockie, who published a very large and important collection of Highland airs in 1816, took much pains, in conjunction with a musical friend, to form what he terms a 'standard.' As he had no taste for the old tonality, he introduces the major seventh in minor keys, and his versions generally abound in semitones. He professed a liking for simplicity, and is not sparing of his abuse of MacGibbon and Oswald for their departures from it; yet his own turns, and shakes, and florid passages, prove that he did not carry his theory into practice. As however a large portion of his volume is occupied with tunes composed during the latter part of the last century and the beginning of the present, in these it would be affectation to expect any other than the modern tonality. A specimen of what he says is an ancient Ossianic air is given as a contrast to that selected from Patrick Macdonald. In style it evidently belongs to a date much nearer to the times of MacPherson than to those of Ossian.

An air to which Ossian is recited.

It cannot be denied that though by his alterations of the forms of Gaelic melody Fraser may have rendered them more acceptable to modern ears, he has undoubtedly shorn the received versions of much of their claim to antiquity. The volume recently published by the Gaelic Society of London (1876), though not faultless in regard to modern changes, has restored some of the old readings; one example ought to be quoted, for the air 'Mairi bhan og' is very beautiful, and the F♮ in the fourth bar gives us back the simplicity and force of ancient times.

Mairi bhan og. (Mary fair and young.)

Captain Fraser stigmatises the previous collections of Patrick Macdonald and Alexander Campbell (Albyn's Anthology) as very incorrect. But Eraser's own versions have in many cases been much altered in the second edition (1876), while more recent works—notably that issued by the Gaelic Society of London—differ most remarkably from earlier copies. The airs are evidently still in a plastic state, every glen, almost every family seems to have its own version. It may perhaps be admitted that those of Fraser, when divested of his tawdry embellishments and chromatic intervals may be found to represent fairly the general taste of the present day.

There has been a good deal of controversy in former times about Highland and Lowland, Irish and Gaelic claims to certain melodies: most of the former seem pretty well settled, but both Irish and Gael still hold to 'Lochaber.' That it is Celtic is apparent from its style, but whether Hiberno- or Scoto-Celtic is not so clear. The earliest documentary evidence for the tune is a Scotish MS. of 1690 (?)—afterwards the property of Dr. Leyden—where it is called 'King James' march to Ireland.' Macaulay, again, says that an Irish tune was chosen for James' march; but it must not be forgotten that in Scotland at that time and for more than a century later, the term Irish was used whenever anything connected with the Highlands was spoken of. The language was called indifferently Irish, Eerish, Ersch, and Erse; so that the Scots themselves would then style the tune Irish while they meant Highland or Gaelic. Of course the air could not at that time be known as 'Lochaber,' for Allan Ramsay did not write his celebrated song till more than twenty years after that date; but no doubt it had a Gaelic name, now apparently lost. It had a Lowland name however, for Burns found it in Ayrshire as the tune of the old ballad 'Lord Ronald my son,' which is traditional not only in that county, but also in Ettrick forest, where Sir Walter Scott recovered it under the name of 'Lord Randal.' As this version consists of one part only, it is believed to be the most ancient now known. Mr. Chappell has recently pointed out that the air seems to have first appeared in print in the 'Dancing Master' of 1701, under the name of 'Reeve's Maggot,' so that but for the style England might almost make some claim to the tune. As for the allegation that Thomas Duffet's song 'Since Celia's my foe,' written 1675, was originally sung to it, Mr. Chappell has shown that to be an error. He prints the original Irish tune of 'Celia,' and also a very good version of 'Lochaber,' which superseded it about 1730. (See Ballad Society's 'Roxburgh Ballads,' part 8.) Bunting, who claims the air under the name of 'Limerick's Lamentation,' prints what he seems to think is the original version in his volume of 1809. It is certainly one of the worst that has ever appeared, and if being overlaid with what is called the 'Scotch snap' will make it Scotish, then no further evidence would be required of the strength of the Gaelic claim. The version is so peculiar, and so little known, that it is given below. Much more might no doubt be said on both sides, in all likelihood without coming to any definite conclusion; the composition of the tune may therefore be left as a moot point; both countries have indeed so many fine airs that they can afford to leave it so.

![{ \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \key ees \major \time 3/4 \partial 4 \relative e' {

\repeat volta 2 {

ees8. f16 | g4 bes16 g8. f16 ees8. |

f4 ees ees8. f16 | g4 bes16 g8. f16 ees8. | %eol 1

f2 ees8. f16 | g16 ees8. aes16 f8. g16 ees8. |

c8. bes16 c4 ees8. f16 | g4 ees ees8. f16 | ees2 } %eol 2

ees8. f16 | g4 bes bes8. c16 | bes4 aes8 g f g |

ees4 ees' ees8. f16 | ees2 ees,8. f16 | g4 bes bes8. c16 | %eol 3

bes4 a8 g f g | ees4 ees' ees8. f16 |

ees2 bes8 c | des16[ c8. des16 ees8. f16 des8.] | %eol 4

c16[ bes8. c16 des8. ees16 c8.] | bes8.[ c16 ees8 g,] f ees |

f2 ees8 f | g16[ ees8. aes16 f8. g16 ees8.] | %eol 5

c8. bes16 c4 ees8. f16 | g4 ees ees | ees2 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/2/k/2ktv219dj8d6v7ntqkuzsnj08v6kg3g/2ktv219d.png)

It is evident from the examples given by Patrick Macdonald that in the most ancient times Gaelic music was devoid of rhythm. The Ossianic chants are short and wild. They are succeeded by longer musical phrases, well suited it may be to heighten the effect of the Gaelic verse, but apart from that, formless, and uninteresting as mere music. From these emerge airs still wild and irregular, but with a certain sublimity arising from their very vagueness. Even when they become more rhythmic, the airs do not at once settle down into phrases of twos and fours, but retain an easy indifference to regularity; two alternating with three, four with five bars, and this in so charming a way that the ease and singularity are alone apparent. The air 'Morag' may be quoted; other examples will be found in Albyn's Anthology 1816–18, and in 'Orain na h-Albain,' an excellent collection of Gaelic airs made by Miss Bell and edited by Finlay Dun.

A glance at some of our printed collections of Scotish airs may not be uninteresting.

The earliest, and the only one known to have appeared in Scotland in the 17th century, is that usually called 'Forbes's Cantus,' from the name of the publisher. The first edition of it was printed at Aberdeen in 1662, a second and third following in 1666 and 1682. It was intended for tuition, and contains the soprano (or cantus) parts only of short pieces for 3, 4, and 5 voices. The other voice parts were probably never printed, for a few copies only would be wanted for use at examinations and exhibitions of the pupils, and these would doubtless be supplied in MS.; it is not therefore surprising that none are known to exist. The work was evidently a compilation of pieces, chiefly in the scholastic style of the time. Some of them, set to Scotish words by Montgomery and Scot, are probably of home origin; others are certainly English, notably Morley's ballet 'Now is the month of Maying,' and three ballad tunes, 'Fortune my foe,' 'Crimson velvet,' and 'Love will find out the way.' The first of these—set to 'Sathan my foe full of iniquity'—Mr. Chappell informs us, was known as the Hanging tune, from 'the metrical lamentations of extraordinary criminals being always chanted to it.' The only tune in the volume with any Scotish characteristics is 'The gowans are gay, my jo,' which is written on four notes, and ends on the second of the scale. It is easy to see that popular Scotish tunes were intentionally avoided, as the object of the work was to teach the young to read at sight, and not to sing by ear.

The next Scotish publication is that of Allan Ramsay, who did much to secure many of our old songs and tunes from further chance of being lost by his 'Tea Table Miscellany,' 1724, and by the little volume containing the airs of the principal songs, 1726. No doubt his chief object in this work was to give new and more decorous words for the old airs, and in some instances may thus have secured their coming down to us. His 'Gentle Shepherd' (1736, with music) did the same good office. Previous to this there had been several publications in England which contained a few Scotish airs. 'The Dancing Master,' brought out by John Playford in 1651, and re-issued with constant additions up to the 17th edition in 1721, contained a very few. Two of these may be named, 'The broom of the Cowden Knowes,' and 'Katherine ogie'; the former has a close on the second of the key, and the latter, though slightly altered in 'The Dancing Master,' is pentatonic in 'Apollo's Banquet,' 1690, and in Graham's Flute-book, 1694. It must be admitted that the work contains a considerably larger number of English airs, which having become favourites on the north of the border, and had good songs written to them, are now stoutly maintained to be Scotish. The 'Oyle of Barley' has become 'Up in the morning early'; 'A health to Betty,' 'My mither's ay glowrin o'er me'; 'Buff coat' is 'The deuks dang owre mydaddie'; 'The Hemp dresser,' 'The deil cam fiddling thro' the town'; and this does not by any means complete the list of our obligations to our southern neighbours. Mr. Wm. Chappell's excellent work has done much to enlighten us on this subject.

The earliest collection professing to contain Scotish melodies only is that published by Henry Playford (London, 1700). His title is 'A Collection of Original Scotch-Tunes (Full of the Highland Humours) for tba Violin. Being the First of this Kind yet Printed.' A large portion of the work consists of dance tunes—Scotish measures chiefly—to many of which words have since been written. Among the true vocal melodies are found for the first time 'Bessie Bell,' 'The Collier's dochter,' 'My wife has ta'en the gee,' 'Widow are ye wauken,' 'Good night and joy be with you,' 'For old (lang) syne, my jo,' 'Allan water,' and 'Wae's my heart that we maun sunder.' We are thus particular because there is but one known copy of the work in existence. It is now the property of Alex. W. Inglis, Esq., of Edinburgh. Unlike many, who are chary of sharing their treasures with others, he is at present preparing a fac-simile of the little volume, for private distribution; and it is perhaps no indiscretion to add that some other rare works may follow, with annotations, or possibly a dissertation on the subject of Scotish music, to which Mr. Inglis's well-known tastes have led him to give considerable attention. This work was succeeded in 1725 by the 'Orpheus Caledonius,' the first collection in which the words were united to the melodies. The editor of the work, William Thomson, does not appear to have been a man of much research or to have known very much of his subject. His versions of the airs are frequently not very good, and occasionally he not only uses English words for the tunes, but even includes some English melodies in the work. He was a singer with a fine voice and a 'sweet pathetic style,' was a favourite at court, where his services were often in demand. The volume contained 50 melodies, and was dedicated to the Princess of Wales—afterwards the Queen Caroline of Jeanie Deans. It must have been successful, as a second edition in two volumes, with double the number of tunes, appeared in 1733. Of the words it may be sufficient to say, that though most of them were great improvements on the older versions, some would not be tolerated in any drawing-room in the days of Queen Victoria.

The number of Collections which appeared in Scotland, from Adam Craig's in 1730 down to our own times, shows how continuously these tunes have held their ground, not in Scotland only, but throughout the three kingdoms. Perhaps the most noteworthy of all is Johnson's 'Museum.' It was issued by an engraver, who, as the preface informs us, intended that its contents should embrace the favourite songs of the day without regard to nationality. Objections having been made to this, he after the first half volume confined it, or at least intended to confine it, to Scotish imisic. Its celebrity has arisen from its connection with Robert Burns, who wrote many of his happiest songs for it, becoming virtually its unpaid editor. His prediction that it would become the text-book of Scotish song for all time, has been amply verified, for modern editors still consult its pages, and future editors must continue to do so. Its first volume appeared in 1787, and its sixth, and last, in 1803; each volume contains 100 airs, many of them taken down from the singing of country girls, and never before in print. Much of this was done by Burns himself; for, as he said, he was ready to beg, borrow, or steal, for the furtherance of the work. It has been doubted whether he possessed sufficient knowledge of music to enable him to note down music; but it has been satisfactorily proved that he played the violin well enough to catch up by ear any easy tunes he heard: that he afterwards transmitted them to Johnson, for arrangement by Stephen Clarke, is known from his letters. The notes written by Wm. Stenhouse for Messrs. Blackwood's new edition of the work are often very valuable; after making every deduction for his persistent wrongheadedness in regard to English music, much solid antiquarian information remains, which must have been utterly lost, but for his persevering researches, added to his personal knowledge. He had however formed a theory that the English had no national music, and whenever any tune was equally known in both kingdoms, he presumed that it necessarily belonged to his own country, thus sending abroad erroneous notions which have been quoted by many authors who have not taken the trouble to verify his statements.

The songs which Burns afterwards wrote for George Thomson's celebrated work are more highly finished, but they often want the ease, the abandon, which form a great part of the charm of Scotish song. They had to pass through the ordeal of fastidious criticism, for the large and handsome volumes in which they appeared, were intended for the highly educated and the wealthy of the land. The musical arrangements were by German musicians of the highest standing, whose scientific knowledge however scarcely made up for their want of acquaintance with the style of the music. The work is now only known through the correspondence which passed between the poet and the editor.

The 'Scotish Minstrel' (1821–24) ought not to be entirely passed over, even in this rapid sketch, as Lady Nairne wrote many of her best songs for it. The work was projected by a coterie of ladies, among whom were Miss Hume (daughter of Baron Hume) and Miss Walker of Dairy. They thought the Scotish muse, notwithstanding all that had been done for her, was still somewhat frank of speech, and they proposed to make her better acquainted with the usages of good society; indeed, they afterwards went so far as to propose a family edition of Burns. Erring stanzas they cut out, or rewrote, and as for drinking-songs they would have none of them. Undoubtedly these ladies were the unacknowledged pioneers of the Temperance movement. Ladv Nairne, who was always very shy of acknowledging her songs, did not make herself known even to her publisher Mr. Purdie but contributed them under the initials of B. B. (Mrs. Bogan of Bogan). There are besides a considerable number of songs signed S[cotish] M[instrel] which have been claimed for her, though it is now believed that they were joint contributions, and not the work of any single individual. The musical part of the work waa done in the simple humdrum sort of fashion appreciated by amateurs of those times. It was the work of R. A. Smith, who though not a great musician has written a few simple Scotish melodies which will not be forgotten. His 'Row weel my Boatie,' is worthy of a wider appreciation than it has yet received.

Later works are legion: that edited by G. F. Graham ought not to be overlooked, on account of the care bestowed on the versions of the melodies; florid passages being expunged, modern alterations—excepting where these were decided improvements restored to the ancient form, and most useful and judicious notes appended to each melody.

One line more maybe added to notice one of the latest and best arrangements of Scotish Melodies, that by Principal Macfarren. To say that it is worthy to stand beside his 'Old English Ditties' is to give it all praise.

[ J. M. W. ]

The following contributions from another pen are given as a supplement to the above paper.

One of the most stirring of the Jacobite songs, and to this day often heard, is 'Awa, Whigs, Awa,' which in Hogg's edition is set to the old tune 'My Dearie an thou dee,' from which is taken the melody of 'What ails this Heart of mine.' In later times, however, it has been sung to a more vigorous tune, which first appeared in the 'Scotish Minstrel,' 1821. It was probably got from Lady Nairne, who took great interest in that work. She was of the family of Oliphant of Gask, well-known adherents of the Stuarts. They were out both in the '15 and the '45, were attainted, and lost their estates. A cadet of the family, equally enthusiastic for the dynasty, repurchased a small part of the property. That he should sing 'Awa, Whigs, awa' with much vigour is not to be doubted; and that the following is his tune seems to be exceedingly probable:—

Awa Whigs, awa!

![{ \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \key bes \major \time 2/4 \partial 8 \relative b' { \autoBeamOff

bes8 | bes4 f8. d16 | bes4 r8 f' |

g16[ c8.] c8. bes16 | a16[ c8.] r8 d | %end line 1

f8. d16 d8. bes16 | bes8. g16 g8. ees16 |

f8. ees16 d8. c16 | bes4.\fermata \bar "||"

f'8 | f16 bes8. bes8. a16 | a8. g16 g8. g16 | g c8. c b16 | %eol 3

bes8 a r d | f8. d16 d8. bes16 | b8. g16 g8. d16 | %eol4

f16 f8. ees8. c16 | c8 bes4 r8 \bar "||" \mark "D.C." }

\addlyrics { A -- wa Whigs, a -- wa! A -- wa Whigs, a -- wa! Ye're but a pack o' trai -- tor loons; Ye'll do nae gude a -- va'. Our this -- tles bloom'd sae fresh and fair, and bon -- nie were our ro -- ses, But Whigs cam like a frost in June and with -- er'd a' our po -- sies. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/k/nk4blihyk3ud6txchmqzqx2ghd95dw0/nk4blihy.png)

This song, when well sung by a staunch Tory, never fails to excite his listeners, being capable of much dramatic expression. It attracted the keen eye of Burns, who though in politics an ardent Whig, was still more a poet. With a poet's comprehensive sympathies and power of appreciating, even when he did not wholly agree, he revised and added to the original verses, so presenting to us the singular anomaly of the greatest of Tory songs being written in part by the greatest of Whig poets. The verses added by Burns are the two beginning 'Our ancient crown's fa'n in the dust,' and 'Grim Vengeance lang has ta'en a nap.'

In contrast to the above air, 'Wae's me for Prince Charlie' is unquestionably one of the most touching of the so-called Jacobite airs. The words were written early in this century by William Glen, a Glasgow manufacturer, who died in 1824. The air appears in the Skene MS., under the name of 'Ladie Cassilis' Lilt,' and in Johnson's 'Museum' under that of 'Johnnie Faa,' or the 'Gypsie Laddie,' the melody being sung to the words of an old ballad beginning 'The Gypsies cam' to our Lord's yett.' Burns, in one of his letters, says that this is the only song that he could ever trace to the extensive county of Ayr.

Wae's me for Prince Charlie. Modern version of the same.

![{ \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/4 \key a \major \partial 8 \relative e' {

\repeat volta 2 {

e8 | e4 e8 fis a4. gis8 | fis e fis a b4. cis8 |

e,4. fis8 a cis b a | fis2 e4. }

a8 | b4 b8 cis e4. fis8 | e cis b cis a4. cis8 | %end line 1

b4. cis8 e4 << { fis4 } \\ { d } >> | cis2 b4 r8 a |

b4 b8 cis e4. fis8 | e[ cis] b a b4. cis8 |

e,4. fis8 a cis b a | fis2 e4. \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/8/h8k9dsr671m2mmcfj8pxu2gjvubb4m1/h8k9dsr6.png)

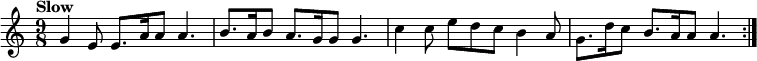

The dance music of Scotland may be said to consist solely of Reels and Strathspeys. Farquhar Graham mentions, in his introduction to the volume of the 'Dance Music of Scotland,' edited by Surenne, that in the oldest MS. collection of Scotish dance tunes, there are to be found Allemands, Branles, Courantes, Gaillards, Gavottes, and Voltes dances imported from France, although not all of French origin; and along with these some Scotish dance tunes, and a few English ones. The foreign dances, however, were confined to the upper classes, the peasantry keeping to their own truly national dances, which have not only survived but have since become fashionable in the highest circles, alike in England and Scotland. The manner of singing or playing on instruments the music of these reels [see Reel, vol. iii. pp. 91–93] and strathspeys is quaintly described by the Rev. Dr. Young in the dissertation prefixed to the collection of Highland airs published by the Rev. Patrick Macdonald in 1781. He says, the St. Kildeans, being great lovers of dancing, met together at the close of the fishing season, and sang and danced, accompanied by the Jew's harp or trump—their only musical instrument. The reverend gentleman adds, 'One or two of these reels sound uncommonly wild even to those who can relish a rough Highland reel.' Some of the notes appear to be borrowed from the cries of the sea-fowl which visit the outer Hebrides at certain seasons of the year. At one time the music of these reels and strathspeys over all Scotland was played by the Bagpipe [see Bagpipe, vol. i. pp. 123–125], but at a later period Neil Gow and his sons did much in promoting the use of the violin in playing Scotish dance music; while in our own day the piano in its turn has to a great extent superseded the violin. The Gow family, with the famous Neil at their head, all showed great originality in their tunes; 'Caller herrin,' by his son Nathaniel, has deservedly taken its place among our vocal melodies, since Lady Nairne wrote her excellent words for it. But it is to be regretted that by changing the characteristic names of many of our old dance tunes, giving them the titles of the leaders of fashion of the day, they have created much uncertainty as to the age, and even the composition, of the tunes themselves. The tempi at winch reels and strathspeys should be taken is naturally to a great extent a matter of taste, or rather of feeling. Farquhar Graham has given the movement of the reel as ![]() = 126 Maelzel, and that of the strathspey as

= 126 Maelzel, and that of the strathspey as ![]() = 94. These tempi are good to begin with, but the exciting nature of the Scotch dances tends to induce the players and dancers to accelerate the speed as the dancing proceeds; a tendency graphically described by Burns in his 'Tam o' Shanter.'

= 94. These tempi are good to begin with, but the exciting nature of the Scotch dances tends to induce the players and dancers to accelerate the speed as the dancing proceeds; a tendency graphically described by Burns in his 'Tam o' Shanter.'

Two of the best specimens we know of this characteristic music are the following:—

Reel. 'Clydeside Lasses.'

Strathspey. 'Tullochgorum.'

![{ \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \key d \major \time 4/4 \partial 8 \relative d'' {

d8 | cis8.[ a16 e'8. a,16] d[ g,8. b8. d16] |

cis8.[ a16 e' a,8.] cis8.[ d16 e a8.] | %end line 1

cis,8.[ a16 e'8. a,16] d[ g,8. b d16] |

cis[ a'8. e d16] d8[ cis b d] |%end line 2

cis8.[ a16 e'8. a,16] d[ g,8. b d16] |

cis8.[ a16 e' a,8.] cis[ d16 e a8.] | %end line 3

cis,8.[ a16 e'8. a,16] d[ g,8. b d16] |

cis[ a'8. e d16] d8[ cis] b \bar "||"

cis | a16[ a'8. e fis16] g8.[ g,16] b4 |

a16[ a'8. e16 a8.] cis,16[ a'8. e16 a8.] | %end line 5

a,16[ a'8. e fis16] g8.[ g,16] b4 |

a16[ a'8. e d16] d8.[ cis16 b8. cis16] | %end line 6

a16[ a'8. e fis16] g8.[ g,16] b4 |

a16[ a'8. e fis16] g8.[ a16 b8. a16] | %end line 7

g8.[ fis16 g8. e16] d[ g,8. b e16] |

a[ e8. a16 cis8.] fis,16[ a8.] e4 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/o/pok0str7zuf1n0n6winjritngtecybq/pok0str7.png)

This tune is an example of the mingled 2nd and 3rd positions of the pentatonic series in the key of D. That is, mixed phrases, now in A now in G.

Much of this old dance music was constructed on the scale of the Bagpipe, which may be regarded as two pentatonic scales placed together,

which are in fact the second and third positions of the pentatonic series in the key of D major. [See p. 444.]

There is reason to fear that the art of singing Scotish songs in their native purity is being rapidly lost; nor is this to be wondered at. The spread of musical education, together with the general use of the piano in all classes of households, must of necessity interfere with the old style of singing Scotish songs in their original and native simplicity. When sung with a piano accompaniment their peculiar charm is in great measure lost; indeed a Scotish song properly rendered is now to be heard only in the rural districts, where on a winter's evening servants and milkmaids sit round the farmer's 'ingle' and 'lilt' in the genuine old traditional style. If Scotish song has suffered at home from the operation of such changes, it can hardly be said to have benefited from the attention it has received in other quarters. Both executants and composers have been attracted by its peculiar qualities, and have sought to bend it to their purposes, or to illustrate it by their genius; in both cases with questionable success. Many great artists have attempted to sing aright some of the finest Scotish airs, but generally without success, at least to Scotish audiences. The really great public exponents of Scotish song were Wilson and Templeton (tenors), both Scotchmen. Though neither was a thoroughly educated musician, both in their youth, without much knowledge of music, learnt by tradition the real art of singing our national airs. Catherine Hayes, so famous for her rendering of Irish airs, comes next as an interpreter of the simple melodies of Scotland. Clara Novello studied to good purpose several of the Jacobite songs; and other exceptionally gifted and cultured artists have been known to rouse their audiences into enthusiasm, though in most cases the result was only a succes d'estime. The attempts of the most illustrous composers to write accompaniments to our national songs have fared no better. And it need not excite much surprise to find that here, as in many similar ill-advised enterprises, the greater the genius, so misapplied, the more signal the failure. Beethoven was employed to write arrangements of Scotish airs, and although all his arrangements bear the impress of his genius, he has too often missed the sentiment of the simple melodies. The versions of the airs sent him must have been wretchedly bad, and they seem to have imbued him with the idea that the 'Scotch snap' was the chief feature in the music. He has introduced this 'snap' in such profusion, even when quite foreign to the air, that the result is at times somewhat comical. Haydn also wrote symphonies and accompaniments to many Scotish airs, and though he succeeded better than his great pupil, still in his case the result, with few exceptions, is not a great success. Weber, Hummel, Pleyel, and Kozeluch were still less happy in their endeavours to illustrate Scotish airs. In later years many musicians have followed the same task. Of the many volumes published we distinctly give the preference to Macfarren's 'Select Scotish Songs'; and yet, admirable as are often Macfarren's settings, it is difficult to get rid of a feeling of elaboration in listening to them. [App. p.791 "at the bottom of the column should be added a notice of the excellent set of twelve Scotish songs arranged by Max Bruch, and published by Leuckart of Breslau."]

To those who are desirous of studying the history of Scotish music, the following works, selected out of a list of nearly 150, may be recommended:—

MS. Collections containing Scotish Melodies.

- Skene MS.—1635 (?). Belongs to the Library of the Faculty of Advocates.

- Straloch MS.—Robert Gordon of Straloch's MS. Lute-book, dated 1627–29. The oldest known MS. containing Scotish airs. The original MS. is a small oblong 8vo, at one time in the library of Charles Burney, Mus. Doc.

- Leyden MS.—1692 (?). Belonged to the celebrated Doctor John Leyden. It is written in Tablature for the Lyra-viol.

Printed Collections.

- Playford's Dancing Master.—1651–1701. Is interesting, as perhaps the earliest printed work that exhibits several genuine Scotish airs.

- D'Urfey's Collection.—Reprint, 1719. Sir John Hawkins, in his History of Music, vol. iv. p. 6, says, 'There are many fine Scots airs in the Collection of Songs by the well-known Tom D'Urfey, intitled Pills to purge Melancholy, published in the year 1720.

- Thomson's Orpheus Caledonius.—1725–1733. This is the earliest Collection of Scotish tunes which contains words with the music.

- Tea-Table Miscellany.—1724. 'Musick for Allan Ramsay's Collection of Scots Songs, set by Alexander Stuart.'

- Adam Craig's Collection.—1730. A Collection of the choicest Scots Tunes.

- James Oswald's Collections.—1740–1742. There are three of these Collections. He published also a larger work under the name of 'The Caledonian Pocket Companion,' in twelve parts.

- Bremner's Collections.—1749-1764. Bremner took great pains to secure the best version of the airs he published, in most cases they are used to this day.

- Neil Stuart's Collections.—Books 1, 2, 3. Thirty Scots Songs adapted for a Voice and Harpsichord. The words of Allan Ramsay.

- Francis Peacock's Airs.—About 1776. A good selection, and good versions.