A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Secco Recitative

SECCO RECITATIVE, accurately Recitativo Secco that is, 'dry' (also R. parlante; Germ. Einfache Recitativ, Sprechende Recitativ; Fr. Recitatif sans Orchestre; Eng. Simple Recitative; Plain Recitative.) The simplest form of Declamatory Music, unrelieved either by Melody, or Rhythm, and accompanied only by a Thoroughbass. [See Recitative.]

It was invented at Florence during the closing years of the 16th century; and first extensively employed, in the year 1600, in Peri's 'Euridice,' and Cavaliere's 'La Rappresentazione dell' Anima e del Corpo.' During the Classical Æra, it was used in Opera and Oratorio as the chief exponent of the Action of the Drama. Rossini first departed from the universal custom, boldly accompanying the whole of the Declamatory Music in 'Otello' by the full Stringed Band. Spohr entirely banished the simpler form of Recitative from the Oratorio, using both Stringed and Wind Instruments in his Accompaniments, throughout Later Composers scorn to use it, even in Opera Buffa. The change of custom, like all other progressive movements, has its advantages and its disadvantages. It increases the interest of Scenes which, deprived of the resources of the Orchestra, might become tedious: but it seriously diminishes the amount of contrast attainable in effects of colouring and chiaroscuro, by depriving the picture of its weaker tones, and thus confining the possible gradation of light and shade within much narrower limits than those which Mozart, Cimarosa, and even Rossini himself, in his earlier years, turned to such splendid account. It is true that advanced Composers endeavour to supply, at the upper end of the scale of effect, a sufficient number of gradations to compensate for those they have cut away from the lower portion of its range: but, there must be a limit to the addition of Sax Tubas and Ophicleides; and, were there none, the contrast between simple Recitative, and even the lowest form of Orchestral Accompaniment, is infinitely stronger, in proportion, than that between the fortissimo of the ordinary Orchestra, and any amount of extra power that can be added to it.[1]

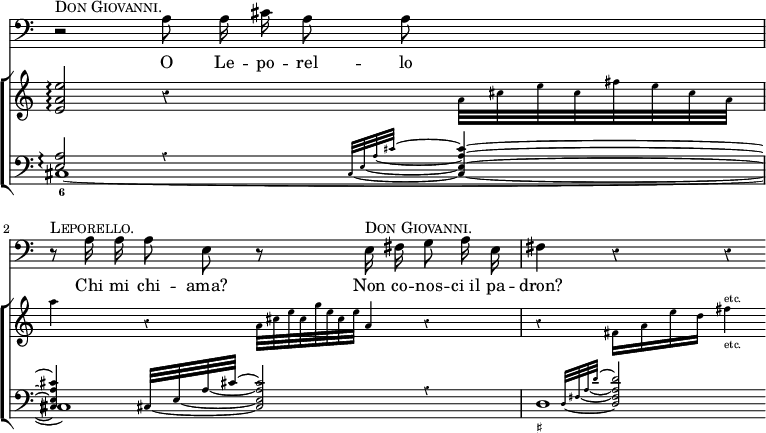

In the 18th century, Recitativo secco was always accompanied by the Stringed Basses alone, the Harmonies indicated beneath the Thoroughbass being filled in on the Harpsichord, Pianoforte, or Organ. As a general rule, these Harmonies were very simply expressed: but, when relief was needed, considerable licence was permitted to the Accompanyist. Such a passage as the following might therefore have been accompanied, without any excess of liberty, by the passages indicated in small notes, provided they were sparingly introduced, played lightly, and not brought too prominently forward.

When the Harpsichord and the Pianoforte were banished from the Opera Orchestra, the Accompaniment of Recitativo secco was confided to the principal Violoncello and Double Bass; the former filling in the Harmonies in light Arpeggios, while the latter confined itself to the simple notes of the Basso continuo. In this way, the Recitatives were performed, at Her Majesty's Theatre, for more than half a century, by Lindley and Dragonetti, who always played at the same desk, and accompanied with a perfection attained by no other Artists in the world, though Charles Jane Ashley was considered only second to Lindley in expression and judgment. The general style of their Accompaniment was exceedingly simple, consisting only of plain Chords, played arpeggiando; but occasionally the two old friends would launch out into passages as elaborate as those shown in the following example; Dragonetti playing the large notes, and Lindley the small ones.

![<< \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 4/4

\new Staff { \clef bass \relative c { \autoBeamOff

r4 r8^\markup \caps "Don Giovanni." c16 c f8 f16 f f8 g16 a |

g8 g r16 g^\markup \caps "Leporello" g g g8 d r d16^\markup \caps "Don Giovanni" d |

g8 g r a a f r4 } }

\addlyrics { Per la ma -- no essa allo -- ra me pren -- de An -- co -- ra meg -- lio M' -- acca -- rez -- za, mi_abra -- cci -- a }

\new Staff << \clef bass

\new Voice \relative f, { \teeny

<f c' a'>4\arpeggio s2. |

f'8\rest f16\rest \afterGrace b,!( { d f g f } \grace b8)

f8\rest f16\rest d( f g b g d'8) r |

f,8\rest f16\rest g([ b d)] f8 f,8*3/2\rest

a'4*1/8^> f8*1/4[ d b g] f[ d b d] g,4*1/8 | }

\new Voice \relative f { f1 | b, _~ b } >>

\figures { s1 <6 4> } >>](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/2/32h3lo201ngpfoh6utdl6k5qlayoppq/32h3lo20.png)

[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ See the account of Recitativo Stromentato, p. 85.