A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Sketches

SKETCHES. SKETCH-BOOKS. SKETCHING, the practice of. A broad distinction must be drawn between the preliminary Sketches made during the progress of a great work, and the modest Movements described in the foregoing article. Though called by the same name, the two forms have nothing whatever in common.

One of the most accomplished Art-critics of modern times assures us that the conceptions of true genius invariably present themselves to the inspired imagination, even in their earliest manifestation, in a complete and perfect form; that they spring from the Artist's brain, as Minerva, adult, and fully armed, sprang from the forehead of Jupiter. No doubt, this is true enough, in a certain sense; but, only so far as the general form of the idea is concerned. Among the treasures presented to the University of Oxford by the late Mr. Chambers Hall, there is a little square of paper, which, if we attempt to press the canon beyond a certain point, cuts away the ground from under it. On one side of this priceless sheet is drawn the seated figure of a female skeleton, surrounded by faint lines indicating the contours of its delicate covering of flesh. On the other, is presented the figure of the Holy Child, exquisitely drawn with the bistre pen, yet not finished with sufficient care to satisfy the Artist, who has several times repeated the feet, with certain changes of position, on the margin of the paper. Now, these studies were made by Raffaelle himself, in preparation for the famous picture known as 'La bella Giardiniera'; and they prove, when compared with the finished painting in the Gallery of the Louvre, that, though the general features of the subject may have presented themselves to the Artist's mind, in the form of an instantaneous revelation, its details suffered many changes of intention, before they perfectly satisfied the mind of their creator.

The Musician deals with his Composition as Raffaelle dealt with this wonderful picture. Each Master, it is true, has his own way of working. Some writers are known to have refrained from committing their ideas to paper, until they had first perfected them, in all their details; though we cannot doubt that they modified those details, many times, and very extensively, by means of some clear process of mental elaboration, before they began to write. Others have left innumerable MS. copies of their several works, each one complete in itself, but differing, in some more or less important particular, from all its fellows. Some very great writers made one single copy serve for all purposes; obliterating notes, and crossing out long passages, at every change of intention; and so disfiguring their MSS., by blots and erasures, that those only who have carefully studied their handwriting can be trusted to decypher them. Others, again—the Sketchers, par excellence—began even their greatest works by noting down a few scraps of Subject, which they afterwards modified, enlarged, and improved; scribbling a dozen different ideas on the back of a single sheet of paper, or in the random pages of a note-book; and changing their plans so frequently, that, when a complete copy was written out at last, it was only by careful examination that the germ of the original thought could be recognised in any part of it. It is impossible to say which of these methods of Composition is the best; for the greatest of the Great Masters have used them all; each one selecting that which best accorded with the bias of his own individual genius. Let us consider a few examples of each; for, no lessons are so precious as those which the Master permits us to learn, for ourselves, while watching him at work in his atelier.

And, first, let us clearly bear in mind the difference between a Sketch and an unfinished Picture. The analogy, in these matters, between Music and Painting is very striking, and will help us much. In both, the Sketch is made while the Artist's mind is in doubt. When his plan is fully matured—and not before—he draws its outline upon his canvas, or lays out the skeleton of his Score upon paper, leaving the details to be filled in at his leisure. The Sketch is never used again; but the outline is gradually wrought into a finished Picture; the skeleton Score, into a perfect Composition. Should the completion of the work be interrupted, the Sketches remain in evidence of the Artist's changes of intention, while the half-covered canvas, or the half-filled Score, show the foundation of his ripe idea, with just so much of the superstructure as he had time or inclination to build upon it. Among our promised examples, we shall call the reader's attention to MS. reliques of both classes.

The earliest known example of a bonâ fide Sketch—like the earliest Rota, the earliest Polyphonic Motet, and the earliest specimen of a Vocal Score—is a product of our own English School. It dates from the middle of the 16th century; and was written, by John Shepherde, either for the purpose of testing the capabilities of a Subject which he intended to use as the basis of a Motet, or other Vocal Composition, or, for the instruction of a pupil.[1] Our knowledge of Shepherde's Compositions is too limited to allow of the identification of the particular work to which this passage belongs; but, by a curious coincidence, the Subject corresponds exactly with that of the 'Gloria' of Dr. Tye's Mass, 'Euge bone,' though its treatment is altogether different.

We doubt whether it would be possible to find a pendant to this very interesting example; for the Polyphonic Composers seem generally to have refrained from committing their ideas to paper, until they were perfected. So far was Pitoni, one of the last of the race, from advocating this habit of sketching, that he is said to have once written out a Mass for twelve Choirs in separate Parts, beginning with the Bass of the Twelfth Choir, and finishing each Part before he began the next—an effort which, if it did not rest upon good evidence, we should regard as incredible.

Sebastian Bach does not appear to have been addicted to the practice of sketching; but, like Painters, who can never refrain from retouching their Pictures so long as they remain in the studio, he seems to have been possessed by an almost morbid passion for altering his finished Compositions. Autograph copies of a vast number of his Fugues are in existence, changed, sometimes, for the better, and sometimes, it cannot be denied, for the worse. Some twenty years ago, an edition of the 'Wohltemperirte Clavier' was published at Wolfenbüttel, giving different readings of innumerable passages, and, with singular perversity, almost always selecting the least happy one for insertion in the text. The Subject of the first Fugue, in C major, exists, in different MSS., as at a, and at b, in the following examples; and, as Professor Macfarren has pointed out, the change is not a mere melodic one, but seriously affects the Counterpoint.

In the Fifth Fugue, in D major, the Subject, at a certain bar, is given in one copy in the original key, and in another in the Relative Minor. A hundred other examples might be cited; but these will show the Composer's method of working, and prove that, though he made no trial Sketches in the earlier stage of the process, he was no less subject to changes of intention afterwards than the most fastidious of his brethren.

Handel, as a general rule, wrote currente calamo; making but a single copy, and frequently completing it without the necessity for a single erasure. But though his pen was emphatically that 'of a ready writer,' it could not always keep pace with the impetuosity of his genius; nor were his ideas always unaccompanied by instantaneous afterthoughts: and in these cases he altered the MS. as he proceeded, with reckless disregard to the neatness of its appearance; intruding smears, blots, and scratches, with such prodigality, that it is sometimes not a little difficult to understand his final decision. But these changes bear such unmistakable evidence of having been suggested at the moment, that they can scarcely be regarded as afterthoughts. When he really changed his mind—as in 'Rejoice greatly,' 'But who may abide?' and 'Why do the nations?'—he made a second copy. Sometimes, also, he made a Sketch. Very few examples of such preparatory studies have been preserved; but these few are of indescribable interest. Among others, the Fitzwilliam Library at Cambridge possesses one, which can only be compared to a 'trial plate' of Rembrandt's. This priceless fragment—here published for the first time—is a study for the 'Amen' Chorus in the 'Messiah.' Before deciding upon the well-known passage of Canonic Imitation, which forms so striking a feature in this wonderful Movement, the Composer has tested the capabilities of his subject, as Shepherde tested his, two hundred years before him; only, not content with trying it once, he has tried it three times, at different distances, and in the inverted form. The identity of the passages marked (a), (b), and (c), with those of the finished Chorus marked (e), (d), and (f), is indisputable; though the Sketches are in the key of C, and in Alla breve time.

The connection of these passages exemplifies the legitimate use of the Sketch in a very instructive manner.[2] Having first tried the possibilities of his Subject, Handel decided upon the form of Imitation which best suited his purpose, and then wavered no more. The complete Score of the Chorus shows no signs of hesitation, in this particular, though the opening of the Fugue exhibits strong traces of reconsideration. The primary Subject, which now stands as at (h), was first written as at (g); and the rejected notes are roughly crossed out with the pen, in the original autograph, to make room for the afterthought. The Movement, therefore, affords us examples both of preliminary Sketches and an amended whole.

Mozart almost always completed his Compositions before committing any portion of them to writing. Knowing this—as we do, on no less positive authority than that of his own word—we find no difficulty in understanding the history of the Overture to 'Il Don Giovanni.' The vulgar tradition is, that he postponed the preparation of this great work, from sheer slothfulness, until the evening before the production of the Opera; and, even then, kept the copyists waiting, while he completed his MS. The true story is, that he kept it back, for the purpose of reconsideration, until the very last moment, when, though almost fainting from fatigue, he wrote it out, without a mistake, while his wife kept him awake by telling him the most laughable Volksmärchen she could remember. It is clear that, in this case, the process of transcription was a purely mechanical one. He knew his work go perfectly, by heart, that the peals of laughter excited by his wife's absurd stories did not prevent him from producing a MS. which, delivered to the copyists sheet by sheet as he completed it, furnished the text of the Orchestral Parts from which the Overture was played, without farther correction, and without rehearsal. But, he had not always time to carry out this process of mental elaboration so completely. Though he made no preliminary Sketches of his Compositions, he not unfrequently introduced considerable changes into the finished copy. Some curious instances of such pentimenti may be found in the autograph Score of the Zauberflöte, in the André collection at Offenbach. Not only are there changes in the Overture; but in the Duet for Pamina and Papageno, in the First Act, the position of the bars has been altered from beginning to end, in order to remedy an oversight in the rhythm, which caused the last note of the last vocal phrase to fall in the middle of a bar instead of at the beginning. Again, the Score of the Pianoforte Concerto in C minor (K. 491), now in the possession of Mr. Otto Goldschmidt, abounds with afterthoughts, many of which are of great importance: yet this MS. cannot be fairly called a Sketch, since the pentimenti are strictly confined to the Solo Part, the orchestral portions of the work remaining untouched, throughout. Strange to say, the work in which we should most confidently have expected to find traces of reconsideration is singularly free from them. So far as it goes, the original MS. (Urschrift) of the 'Requiem' is a finished outline, written with so fixed an intention, that it needed only the filling in of the missing details, in order to make it perfect—a circumstance for which Süssmayer must have felt intensely thankful, if we may believe that no other records were left for his guidance.

A more remarkable contrast than that presented by these firm outlines to the rough memoranda of the Composer who next claims our attention, it would be impossible to conceive. Beethoven's method of working differed, not only from Mozart's, but from that of all other known men of genius; and that so widely, that, if we are to accept the canon laid down by the author of 'Modern Painters' at all, it can only be on condition that we regard him as the exception necessary to prove the rule. His greatest works sprang, almost invariably, from germs of such apparent insignificance, that, were we unable to identify their after-growth, we should leave them unnoticed among the host of barely legible memoranda by which they were surrounded. Happily, it was not his habit to destroy such memoranda, after they had fulfilled their office. He left behind him a whole library of Sketchbooks, the value of which is now fully recognised, and, thanks to the unremitting industry of Nottebohm and Thayer, not likely to be forgotten. Of the three specimens now in the British Museum, one is a mere fragment, and another, of comparatively trifling interest; but the third (Add. MSS. 29,801), contains some extremely valuable sketched memoranda, made during the progress of the Music for 'The Ruins of Athens,' 'Adelaida,' the little Sonata in G minor (Op. 49, No. 1), and numerous other works, including a complete copy of the 'Sonatina per il Mandolino' already printed at p. 205 of our second volume. More interesting still are some of the Sketch-books in the Royal Library at Berlin. From one of these, written between the years 1802–4, and carefully analysed by Nottebohm,[3] we extract a series of records connected with the Sonata in C major, Op. 53, dedicated to Count Waldstein—a work so generally known, that our readers can scarcely fail to take an interest in the history of its birth, infancy, and development to maturity. The first Sketch, at page 120, dashes into the Subject of the opening Allegro, by aid of a few prefatorial bars which go far to induce our belief in some still earlier memorandum.

At page 122 follows the first idea of the Modulation which introduces the Second Subject.

The Second Subject itself first appears at p. 123, in G; and in a form far inferior to that in which it makes its first entrance, in E, in the finished Sonata.

The close of the First Part is suggested on p. 122.

On p. 123 we find a Sketch for the opening of the Second Part—

and, on p. 131, the close of the Movement.

Alternating with these memoranda, the volume presents some intensely interesting Sketches for an Andante, the first suggestion for which appears at p. 121, in E major.

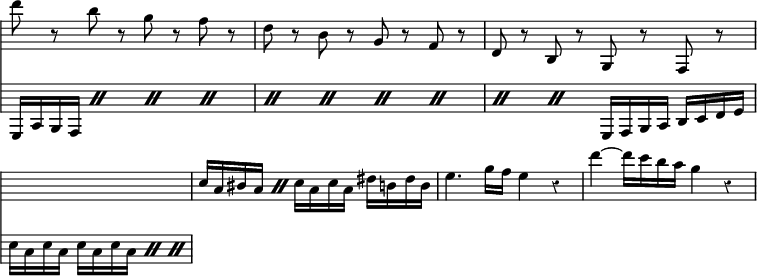

![{ << \new Staff \relative g' { \key e \major \tempo "Andante." \time 3/8 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \partial 8

gis16. a32 | fis8[ b] e,16. fis32 | dis8[ gis] cis,16. dis32 |

e8. fis16 gis a | gis8 fis }

\new Staff \relative e' { \key e \major \clef bass

e8 | dis[ b] cis | b[ gis] a | gis8.[ dis16 e a,] | b8 b' } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/k/3kd6opc8a9qt4sobjxu8iww49ncamnx/3kd6opc8.png)

Immediately afterwards, this first idea reappears, in a modified form, and in combination with a phrase justly dear to all of us.

![{ << \new Staff \relative b' { \key e \major \time 3/8 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Staff.Clef #'stencil = ##f \partial 8

b32( gis) b( gis) | a8[ fis] fis'32 dis fis dis |

e8[ b] b16. cis32 | b8[ a16 gis fis gis] | gis8[ a] a16. b32 }

\new Staff \relative g { \clef bass \key e \major \once \override Staff.Clef #'stencil = ##f

gis32 e gis e | fis8[ dis] \clef treble a''32 fis a fis |

gis8 e s | s4. s } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/t/r/trp9t9l9sjq55pbwmmn4nzmiryrwt5c/trp9t9l9.png)

The Key is afterwards changed, and the idea assumes a familiar form—

![{ << \new Staff \relative c'' { \key f \major \time 3/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \partial 4 \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f)

c8. d16 | c4 bes a8. bes16 | a4 g f8. fis16 |

g4. a8 bes g | f!4 e c'8. d16 | %end line 1

c4 bes a8. bes16 | a4 g f8. g16 | a4. c8 bes g | f4 r a8. b16 %eol2

c2 a16 g a b | c2 a16 g a b | c bes c d e4 d | c2 des8. des16 %eol3

des8. aes16 f4 des'8. des16 | d8. a16 f4 f'8. f16 |

f4. des8 c b | bes4 c c8. d16 | %end line 4

c4 bes a8. bes16 | a4 g f8. g16 |

<< { a4 } \\ { cis,8[ c] } >> bes' g f e | g4 f8 \bar "||" }

\new Staff \with { \RemoveAllEmptyStaves } \relative a, { \override Staff.Clef #'stencil = ##f \key f \major \clef bass

s4 s2. s s s | s s s s | s s s s | s s s s |

s s | a8 d g, bes c c | f,[ f' f,] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/d/5dtwl4su04wktzttg9un52d92uwzmd7/5dtwl4su.png)

The Movement now gradually developes into the well-known Andante in F, known as Op. 35, though, as Ries tells us, originally included in the plan of the Sonata we are studying:—

![{ \relative c'' { \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/8 \partial 8 \key f \major

c32 a c a | bes8[ g] g'16 e g e | f8[ c] c32 a c a |

bes8[ g] g'16[ e g e] | f4 f8 ~ | %end line 1

f4 ees8 | des8. ees16 des ees | f4 ees8 |

des4 des16 c | c b b8[ b] | c } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/3/n/3ng0ghh3pt72zm2t9h6ug61izxb5u54/3ng0ghh3.png)

Still, this passage does not satisfy the Composer, who tries it over and over again; always, however, retaining the lovely Modulation to the key of D♭, and gradually bringing it into the form in which it was eventually printed.

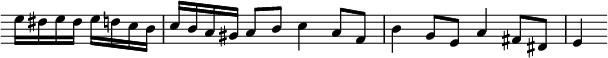

We next find a suggestion for the Episode in B♭,

and, lastly, the germ of the Coda.

![{ \relative c' { \time 3/8 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \once \override Score.Clef #'stencil = ##f \partial 8

c32 a c a | f'4[ c] a'32 f a f |

c'8[ a] \ottava #1 f''16 c f c | f8 c a | \ottava #0 f c a %eol 1

f c a | \clef bass f4. | ges \bar "" aes4*3/2 \bar ""

ges'8 r r | << { e!8 e e | f } \\ { c, c c | f, } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/a/9/a9fx4s1i6olur9sr8iv6iae1qyhbkm4/a9fx4s1i.png)

The alternation of these Sketches with those for the first and last Movements of the Sonata, coupled with the absence of all trace of a design for the intermediate Movement which now forms part of it, sufficiently corroborates Ries's assertion that the publication of the 'Andante in F,' in a separate form, was an afterthought; while the eminent fitness of this beautiful Movement for the position it was originally intended to fill, tempts us to regret that the 'Waldstein Sonata' should ever have been given to the world without it. But the whole work suffered changes of the most momentous character. The Rondo was originally sketched in Triple Time, though that idea was soon abandoned, in favour of one which, after several trials, more clearly foreshadowed the present Movement; not, however, without long-continued hesitation between a plain and a syncopated form of the principal Subject.

The two following Sketches for the middle section of the Movement, are chiefly remarkable for the change suggested in the second memorandum.

The passage of Triplets, which afterwards forms so important a feature of the Movement, is first suggested at p. 137, and its future development indicated by the word Triolen on p. 139.

Then follows the introduction of a new idea:—

![{ \relative c { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \once \override Score.Clef #'stencil = ##f \clef bass

\repeat tremolo 4 { <c a>16 e } \clef treble \ottava #1 e'''8 e

\time 2/4 e,[ e] gis gis | a4 b16 d c b | c e d c b d c b | a4 } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/h/dhykw4rszpb1s4pdyej924rn7r7m2n7/dhykw4rs.png)

Finally, on p. 138, we find the first rough draft of the Prestissimo with which the work concludes—or, rather, the embryo which afterwards developed itself into that fiery peroration.

![{ \relative g'' { \tempo "Presto." \time 2/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Clef #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

g4. fis16 g | e8[ dis e c] | d[ cis d g,] | c[ e g g] | g[ g fis g]

e[ dis e c] | d[ cis d g,] | c[ e g g] \ottava #1

g'[ g fis g] | e[ dis e c] | %end line 2

d[ cis d g,] | c[ e g e] | d[ cis d g,] | c[ e g e] | d[ cis d g,]

c[ g c e] | g,[ e g c] | \ottava #0

e,[ c e g] | c,[ g c e] | g,[ e g c] | %end line 4

\repeat percent 3 { e,[ c e g] } c r r4 |

<g' g'>8 r r4 | c2\fermata \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/o/koiqgfohur0d8vatnal09z2tga5do0g/koiqgfoh.png)

The Sonata, in its present form, consisting of the Allegro, and the Rondo, with a short 'Introduzione'—of which no Sketch has as yet been found—interposed between them, was published, as Op. 53, in May 1805, and the Andante, in a separate form, as Op. 35, in May 1806. The Sketches belong, in all probability, to the year 1803: and the volume which contains them is even richer in records of the 'Eroica Symphony'; besides furnishing valuable memoranda for the treatment of the First Act of 'Fidelio,' the Pianoforte Concerto in G major, the Symphony in C minor, and other works of less importance. The Sketches for the Eroica Symphony exceed in interest almost all the others we possess; but we have thought it better to illustrate our subject by those for the Sonata, because, being both less voluminous, and more easily compared with the finished work, these 'vestiges of creation' exhibit the peculiar phase of productive power we are now studying in a more generally intelligible form than any others that we could have selected, and, while forcibly reminding us of the process carried out by Raffaelle, in designing the 'Bella Giardiniera,' very clearly exemplify the points in which Beethoven's plan of action diverged from that pursued by other Classical Composers.

Schubert's method of working differed entirely both from Mozart's, and Beethoven's. He neither prepared a perfect mental copy, like the former; nor worked out his ideas, as did the latter, from a primordial germ; but wrote almost always on the spur of the moment, committing to paper, as fast as his pen could trace them, the ideas which presented themselves to his mind at the instant of composition—proceeding, in fact, as ordinary men do when they sit down to write a letter. This being the case—and there is ample proof of it—we are not surprised to find that he was no Sketcher, though we cannot but regard with astonishment the remarkable freedom of his Scores from evidences of afterthought. It is true, we do sometimes find important modifications of the first idea. There is an autograph copy of 'Der Erlkönig' in existence—probably an early one—in which the Accompaniment is treated in Quavers, in place of Triplets.[4] Important changes have been discovered in the Score of the Mass in A♭.[5] Others are found in the Symphony in C major, No. 10; the original MS. of which gives proof, in many places, of notable changes of intention. A singularly happy improvement is effected in the opening Theme, for the Horns, by the alteration of a single note. The Subject of the Allegro is far more extensively changed; and scratched through with the pen, at every recurrence, for the introduction of the later modification. New bars—and very beautiful ones—have been added to the Scherzo; and there is more or less change in the Adagio. But, these cases are far from common. As a general rule, he committed his ideas to paper under the influence of uncontrollable inspiration, and then cast his work aside, to make room for newer manifestations of creative power. By far the greater number of his MSS. remain, untouched, exactly in the condition in which they first saw the light: monuments of the certainty with which true genius realises the perfect embodiment of its sublime conceptions. In no case is this certainty more forcibly expressed than in the unfinished Score of the Symphony in E, No. 7, now in the possession of the Editor of this Dictionary.[6] Schubert began to write this, with the evident determination to complete a great work on the spot. At first, he filled in every detail; employing, for the expression of his ideas, the resources of an Orchestra consisting of 2 Violins, Viola, 2 Flutes, 2 Oboes, 2 Clarinets in A, 2 Bassoons, 2 Horns in E, 2 Horns in G, 3 Trombones, 2 Trumpets in E, Drums in E, B, Violoncello, and Contra-Basso. This portion of the Symphony opens thus—

After a farther development, of 30 bars duration, the Adagio breaks into an Allegro in E major:—

![{ << \new Staff << \key e \major \time 4/4

\new Voice \relative g'' { \stemUp \override MultiMeasureRest.staff-position = #2

R1 | r2^\markup \small "Viol. 1mo" r8. gis16^.\pp gis8.^. a16^.|

b8^. r b^. r gis^. r e^. r | %end line 1

\repeat unfold 2 { b2 ^~ b8.[ gis16^. gis8.^. a16^.] } %eol 2

b8^( cis b dis e b' gis e) | e2^>^( dis8) s_"etc." }

\new Voice \relative g' { \stemDown

<gis b>_.\pp^\markup \small "Viol. 2 e Viola" q_. q_. q_.

\repeat unfold 3 { q2:8 } | q1:8 | %end line 1

gis1:8 gis: gis: <a b>: } >>

\new Staff << \clef bass \key e \major

\new Voice \relative e' { \stemUp

e8^\markup \small "Cello" e e e e2:8 e: e: e1:8 %end line 1

e1:8 e: e: fis: }

\new Voice \relative e { \stemDown \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

e4_\markup \small "Basso" r r2 R1 R | %end line 1

r8. gis,16-.[_\markup \small "Basso" gis8.-. b16-.] e4-. r |

r8. gis,16-.[ gis8.-. b16-.] e4-. r | %end line 2

R1 fis4 r r2 } >> >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/u/kuos4cajt37kvmjui0oqwnvj8phl6qg/kuos4caj.png)

During the 69 bars which follow, the Movement is fully scored; but, from this point, either through failure of time, or, more probably, in rebellion against the mechanical restraint imposed upon thoughts which flowed faster than the pen could write them down, Schubert indicates the leading thread only of his idea, by means of a few notes, allotted sometimes to one Instrument, and sometimes to another, but always with a firmness of intention which conclusively proves that the entire Score was present to his mind, throughout. Thus, at the 85th bar of the Movement, a few notes for the First Violin introduce the Second Subject, of which the First Clarinet part only is written in full, with here and there a note or two for the Violin, not simply suggested, but resolutely inserted in the proper place.

![{ \new Staff << \key e \major \time 4/4 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

\new Voice \relative b' { \stemUp

s1 b2^(^\markup \small "Clar." a4 g | a2. g4 a b c b a2.)_"etc." }

\new Voice \relative b' { \stemDown

r2_\markup \small "Viol." r8. <b d,>16[\p q8. q16] q4 r } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/x/7xv970ag1geipjznn2a3sgaoom99lij/7xv970ag.png)

In this manner the Movement is carried on through a farther period of 271 bars—in all 374—never with less clear indications than these, and generally with much fuller ones, to its conclusion in the original key. Then follows an Andante in A major, on the following Subject, of which the First Violin part only appears in the MS.

Of this, nine bars only are fully scored, soon after the statement of the leading Subject, and six more a little farther on: but the indications are perfectly clear throughout.

The Scherzo, in C major, also begins with the First Violin part only, no part of it being completely scored:—

The Trio opens with a passage for Oboes, Bassoons, and Viole divisi; and it is possible that some portions of it may have been intended to remain as they stand in the MS., with no additional Instrumentation:—

The last Movement begins, in like manner, with a very meagre outline: but, a large proportion of the First Violin part is completely filled in; and, when a subsidiary Subject makes its appearance, the Wind Instruments never fail to indicate the special mode of treatment intended for it.

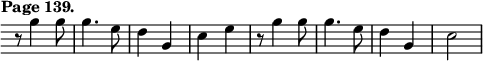

![{ \new Staff << \key e \major \time 2/4 \tempo "Allo. giusto." \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

\new Voice \relative b' { \stemUp \override MultiMeasureRest.staff-position = #2

R2 \bar ".|:" R R r4^\markup \small "Viol. 1mo" r8 b(\p |

e4.-> b8 | gis4) r8 gis( | a)[ b-. cis-. ais-.] |

b4 r8 b( e4.-> b8 | gis4) r8 b( | %end line 2

fis)[ gis-. a-. fisis-.] | gis4 s8_"etc." }

\new Voice \relative b { \stemDown

r8_\markup \small \right-align "Viol. 2ndo" <b gis'>4_>\pp q8 |

q[ q q q] | r8 gis'4 gis8 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/0/503wid4vf01t8lt6hebym3c9ag1i68z/503wid4v.png)

We have said enough to show that, though describable in general terms as 'a Sketch,' this remarkable MS. is not one in reality. It is rather what a Painter would call an ébauche: an outline, indicating the contours of a finished design with a touch so firm, that not one note would have needed alteration, during the process of filling in the later details, had the Composer so far departed from his usual custom as to complete a MS. once laid aside, and forgotten. In truth, it exactly represents a canvas, fully prepared to receive the future painting; and may, therefore, be fairly accepted as evidence that Schubert was not addicted to the practice of sketching, a conclusion which is strengthened by the Score of the unfinished Symphony in B minor, No. 8, the first two Movements of which are completely finished, while, of the remainder, nine bars only were ever committed to writing.

Mendelssohn, on the other hand, sketched freely; though, less for the purpose of registering stray thoughts for future use, than for the sake of the Sketches themselves. Thus, we constantly find him heading a letter with some little passage, through the medium of which he strove to express the feelings of the moment more perfectly than he could have done in words. Still, cases were not wanting, in which he turned the record of some momentary impression to splendid subsequent account. A notable instance of this is afforded by the germ of the Overture to 'The Isles of Fingal,' which first appears in a letter to his family, dated 'Auf einer Hebride, den 7 August, 1829'; and beginning 'To show you how more than ordinarily pleasing I have found the Hebrides, the following has just suggested itself to me.' A facsimile of this interesting memorandum will be found in 'The Mendelssohn Family,' i. 208. A more extended Sketch for two of the Movements of a Symphony in C has been printed in our own vol. ii. p. 305.

We need not quote the memoranda of later writers. We have, indeed, purposely illustrated the subject by aid of examples left us by the greatest of the Great Masters only. And, in contrasting the methods pursued by these great geniuses, we find it no easy task to arrive at a just conclusion with regard to their comparative value. When carefully analysed, the methods of Mozart and Beethoven will be found to bear a closer analogy to each other than we should, at first sight, feel inclined to suppose. Mozart was a mental sketcher; Beethoven, a material one. The former carried on, in his brain, the process which the latter worked out upon paper—et voilà tout. Whether or not the mental embryo was as simple in its origin as the written one, we cannot tell. Probably not. Mozart tells us, that, when he was in a fitting mood for composition, he heard the conceptions which presented themselves to his mind as distinctly as if they had been played by a full Orchestra. But, we know that he gradually brought them to perfection, afterwards: and he himself implied as much, when he said, that, after all, the real perfonnance of the finished work was the best. Beethoven heard his thoughts, also, with the mental ear, even after the material organ had failed to perform its office; and it would be unsafe to assume, that, because he was more careful than Mozart to record his conceptions in writing, their development was really more gradual. If Mozart's mental Sketches could be collected, it is quite possible that they might outnumber Beethoven's written ones. And the same with pentimenti. It matters nothing, when the Composer has determined on a change, whether he puts it on paper at once or not. Two examples will illustrate our meaning, the more forcibly because in neither case is the composition affected by the pentimento. 1. In the original autograph of Mozart's 'Phantasia' in C minor (Köchel no. 475), now in the collection of Mr. Julian Marshall, three flats were, as usual, placed at the signature, in the first instance; but Mozart afterwards erased them, and introduced each flat, where it was needed, as an Accidental. 2. Among the Handel MSS. at Buckingham Palace is a volume labelled 'Sonatas,' which contains two pages of the Harpsichord Suite in E minor, in Alla breve time, with the three B's which begin the subject written as Minims, instead of Crotchets, and the following passage as Quavers. But Schubert only very rarely made such changes as these. He made no sketch either mental or written. The ideaa rushed into the world, in the fullest form of development they were fated to attain. One's first impulse is, to pronounce this the highest manifestation of creative genius. Yet, is it the most natural? Surely not. It is true, we recognise, in the material Creation, the expression of a preconceived Idea, infinitely perfect in all its parts, and infinitely consistent in its unbroken unity and ineffable completeness: but, each individual manifestation of that Idea attains perfection, under our very eyes, by slow development from a primordial germ, to all outward appearance more simple in its construction than the slightest of Beethoven's Sketches. And, if the mortal frame of every man who walks the earth can be proved to have originated in a single nucleated cell, we surely cannot wonder that the 'Pastoral Symphony' was developed from a few notes scratched upon a sheet of music-paper.[ W. S. R. ]

- ↑ Printed by Hawkins, History, App. 10.

- ↑ We believe the musical world is indebted, for the identification of these Sketches, to the late Mr. Vincent Novello, by whom the writer's attention was drawn to the subject.

- ↑ 'Ein Skizzenbuch von Beethoven aus dem Jahre 1803.' etc. B. & H. 1880. This was preceded by an earlier one, containing the 2nd Symphony and other works, and published in 1865.

- ↑ Vide page 324.

- ↑ Vide page 336b.

- ↑ Vide pages 334, 335, and 437b.