A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Solfeggio

SOLFEGGIO, E GORGHEGGIO. Solfeggio is a musical exercise for the voice upon the syllables Ut (or Do), Re, Mi, Fa, Sol, La, forming the Guidonian Hexachord, to which was added later the syllable Si upon the seventh or leadingnote, the whole corresponding to the notes C, D, E, F, G, A, B of the modern Diatonic scale. These names may be considered the result of an accident ingeniously turned to account, the first six being the first syllables of half lines in the first verse of a hymn for the festival of St. John Baptist, occurring upon the successive notes of the rising scale, with a seventh syllable perhaps formed of the initial letters of Sancte Johannes. [See Solmisation.]

The first use of these syllables is ascribed to Guido d'Arezzo as an artificial aid to pupils 'of slow comprehension in learning to read music,' and not as possessing any special virtue in the matter of voice-cultivation; but it is by no means clear that he was the first to use them. At any rate they came into use somewhere about his time. It is probable that even in Guido's day (if voice-cultivation was carried to any grade of perfection—which is hardly likely in an age when nearly all the music was choral, and the capacities of the voice for individual expression were scarcely recognised), as soon as the notes had been learned, the use of syllables was, as it has been later, superseded by vocalisation, or singing upon a vowel. The syllables may be considered, therefore, only in their capacity as names of notes. Dr. Crotch, in his treatise on Harmony, uses them for this purpose in the major key, on the basis of the movable Do, underlining them thus, Do, etc., for the notes of the relative minor scales, and gives them as alternative with the theoretical names—Tonic, or Do; Mediant, or Mi; Dominant, or Sol, etc. The continued use of the syllables, if the Do were fixed, would accustom the student to a certain vowel on a certain note only, and would not tend to facilitate pronunciation throughout the scale. If the Do were movable, though different vowels would be used on different parts of the voice, there would still be the mechanical succession through the transposed scale; and true reading—which Hullah aptly calls 'seeing with the ear and hearing with the eye,' that is to say, the mental identification of a certain sound with a certain sign—would not be taught thereby. Those who possess a natural musical disposition do not require the help of the syllables; and as pronunciation would not be effectually taught by them, especially after one of the most difficult and unsatisfactory vowels had been removed, by the change of Ut to Do, and as they do not contain all the consonants, and as moreover voice-cultivation is much more readily carried out by perfecting vowels before using consonants at all,—it was but natural that vocalisation should have been adopted as the best means of removing inequalities in the voice and difficulties in its management. Crescentini, one of the last male soprani, and a singing-master of great celebrity, says, in the preface to his vocal exercises, 'Gli esercizj sono stati da me imaginati per l'uso del vocalizzo, cosa la piu necessaria per perfezionarsi nel canto dopo lo studio fatto de' solfeggi, o sia, nomenclature delle note'—'I have intended these exercises for vocalisation, which is the most necessary exercise for attaining perfection in singing, after going through the study of the sol-fa, or nomenclature of the notes.' Sometimes a kind of compromise has been adopted in exercises of agility, that syllable being used which comes upon the principal or accented note of a group or division, e.g.

![{ \relative c' { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \override Score.Clef #'stencil = ##f

c16[ d e c] d[ e f d] e[ f g e] f[ g a f] |

c32[ d e f a g f e] %end line 1

d[ e f g b a g f] e[ f g a c b a g] f[ g a b d c b a] }

\addlyrics { Do __ _ _ _ Re __ _ _ _ Mi __ _ _ _ Fa __ _ _ _

Do __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Re __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Mi __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Fa __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/0/d/0d1clab2xfx6k625d2euq4qdfp3k121/0d1clab2.png)

The word 'Solfeggio' is a good deal misused, and confounded with 'Vocalizzo' in spite of the etymology of the two words. The preface to the 4th edition of the 'Solféges d'Italie' says 'La plupart des Solféges nouveaux éxigent qu'ils soient Solfiés sans nommer les notes.' Here is an absurd contradiction, and a confusion of the two distinct operations of Solfeggiare and Vocalizzare. We have no precise equivalent in English for Solfeggio and Solfeggiare. The French have Solfége and Solfier. We say, to Sol-fa, and Sol-faing—a clumsy and ineuphonious verb-substantive. As a question of voice-production, the wisdom of vocalisation, chiefly upon the vowel a, (Italian), and certainly before other vowels are practised, and most decidedly before using consonants, has been abundantly proved. The use of the words in question is not therefore a matter of much importance. This appears to be in direct opposition to the advice of a very fine singer and an eminent master, Pier Francesco Tosi, whose book upon singing was published at Bologna in 1723, the English translation by Galliard appearing in 1742. He says, 'Let the master never be tired in making the scholar sol-fa as long as he finds it necessary; for if he should let him sing upon the vowels too soon, he knows not how to instruct.' 'As long as he finds it necessary,' however, is a considerable qualification. The world lives and learns, and Crescentini's verdict may safely be accepted. The vowel a, rightly pronounced, gives a position of the resonance-chambers most free from impediment, in which the entire volume of air vibrates without after-neutralisation, and consequently communicates its vibrations in their integrity to the outer air; this therefore is the best preparation, the best starting-point for the formation of other vowels. After this vowel is thoroughly mastered others are comparatively easy, whereas if i or u (Italian) are attempted at first, they are usually accompanied by that action of the throat and tongue which prevails to such a disagreeable extent in this country. When the vowels have been conquered, the consonants have a much better chance of proper treatment, and of good behaviour on their own part, than if attacked at the outset of study. Vocalisation upon all the vowels throughout the whole compass of the voice should be practised after the vowel a is perfected; then should come the practice of syllables of all kinds upon all parts of the voice; and then the critical study and practice (much neglected) of recitative.

The words Gorgheggio and Gorgheggiare, from Gorga, an obsolete word for 'throat,' are applied to the singing of birds, and by analogy to the execution of passages requiring a very quick and distinct movement or change of note, such as trills and the different kinds of turn, also re-iterated notes and quick florid passages in general. The English verb 'to warble' is given as the equivalent of gorgheggiare, but warbling is usually accepted to mean a gentle wavering or quavering of the voice, whereas agility and brilliancy are associated with the Italian word. A closer translation, 'throat-singing,' would give a rendering both inadequate and pernicious—inadequate, as throat-singing may be either quick or slow, and pernicious as suggesting unnecessary movement of the larynx, and helping to bring about that defective execution so often heard, in which there is more breath and jar than music, closely resembling unnecessary movement of the hand when using the fingers upon an instrument.[1] The fact is, that execution, however rapid, should be perfect vocalisation in its technical sense, and perfect vocalisation has for its foundation the Portamento. The Portamento (or carrying of the voice—the gradual gliding from one note to another) removes inequalities in the voice, and facilitates the blending of registers. Increased in speed by degrees, the voice learns to shoot from note to note with lightning-like rapidity, and without the above-named convulsion of the larynx which produces a partial or total cessation of sound, or at any rate a deterioration of sound during the instantaneous passage from note to note. It is this perfect passage from note to note, without lifting off or interrupting the voice, that fills space with a flood of sound, of which Jenny Lind's shake and vocalised passages were a bright example. But this kind of vocalisation is the result of years of conscientious practice and the exercise of a strong will; and it is just this practice and strong will that are wanting in the present day. Exercises are not wanting. With such books as those of Garcia, Panseron, Madame Sainton, and Randegger, etc., etc., and of course some special passages for individual requirements, to say nothing of those of Rossini, and the numberless vocalizzi of Bordogni, Nava, etc., etc., the 'Solféges d'Italie,' and the 'Solféges du Conservatoire,' there is work enough if students will avail themselves of it. Tosi, in speaking of the difficulties in teaching and learning the shake says, 'The impatience of the master joins with the despair of the learner, so that they decline farther trouble about it.' A summary mode of getting over difficulties!

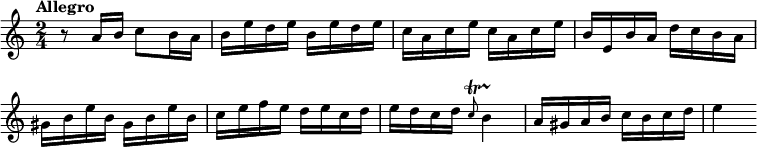

The first of the two great works just named is entitled 'Solféges d'Italie, avec la Basse chiffrée, composés par Durante, Scarlatti, Hasse, Porpora, Mazzoni, Caffaro, David Perez, etc. Dediés à Messeigneurs les premiers Gentilshommes de la chambre du Roi [Louis XV], et recueillis par les Srs. Levesque et Bêche, ordinaires de la Musique de sa Majesté.' The work is therefore obviously a collection of Italian Solfeggi made in France by Frenchmen. Levesque was a baritone in the King's Chapel from 1759 to 1781, and in 1763 became master of the boys, Bêche was an alto. The first edition of the work appeared in 1768; the fourth, published by Cousineau, at Paris in 1786. It forms one large oblong volume, and is in four Divisions: I. The 'indispensable principles' of singing—names of notes, etc., and 62 easy (anonymous) Solfeggi in the G clef with figured bass. II. Solfeggi 63 to 152 for single voices in various clefs—including G clef on 2nd line and F clef on 3rd line—in common, triple, and compound time, all with figured basses. III. Solfeggi 153—241, with changing clefs, and increasing difficulties of modulation and execution—ending with the Exclamationes quoted in the text; all with figured basses. Divisions II and III are by the masters named in the title; each Solfeggio bearing the composer's name. IV. 12 Solfeggi for 2 voices and figured bass by David Perez, each in three or four movements. The forms of fugue and canon are used throughout the work, and some of the exercises would bear to be sung with words. One, by Hasse, is a graceful arietta. A few extracts will show the nature of the work. No. 1 exhibits the kind of instrumental passage that frequently occurs in Scarlatti's solfeggi. No. 2, by Leo, is very difficult, and gives much work to the voice. No. 3, from the exercises for two voices of David Perez, keeps the voice much upon the high notes. No. 4, from the same, requires, and is calculated to bring about, great flexibility. No. 5, by Durante, is curious, and is evidently intended as an exercise in pathetic expression. It has no figured bass, like the other exercises in this collection, but a part in the alto clef, clearly intended for an obbligato instrument, probably for the viol d'amore.

![{ \relative g'' { \time 6/8 \tempo "Allegro" \key ees \major \override Score.BarNumber #'break-visibility = #'#(#f #f #f) \partial 4.

g8\noBeam g,16 c b d | c ees d c b c f, aes' g f ees d | %end line 1

ees c d c b c f, aes' g f ees d |

\grace f8 ees16 d c4 c16 ees d c g' g, | %end line 2

aes g' f ees d ees d ees f aes, g f |

g f ees4 ~ ees16 ees' d f ees8\noBeam ~ | %end line 3

ees16 bes ees, g bes des c f e g f8\noBeam ~ |

f16 c f, a c ees d g fis aes g8\noBeam ~ |

g16 d g, b d f ees g c, ees g, c |

aes c f, aes c[ f] \grace ees8 d4.\startTrillSpan } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/v/bvlzypjqc1eaerkxqknuuz88kbfhghe/bvlzypjq.png)

[2]

But the reader is strongly advised to refer to this remarkable work for himself.

A later and very complete collection of exercises and studies is that published in Paris by Heugel under the title of 'Solféges du Conservatoire, par [3]Cherubini, Catel, Méhul, Gossec, et Langlé,' edited by Edouard Batiste, Professeur de Solfége,' etc. It is in eight volumes 8vo., including a hundred preparatory exercises by Batiste himself. The first exercise in the main collection is a short theme with 57 variations. The studies increase in difficulty, and the later ones require great powers of vocalisation. Those by Gossec abound in reiterated notes and in passages of extended compass. There are duets and trios, some of which are very elaborate. A curious one by Cherubini is in free fugal imitation, with the respective entries of the second and third voices taking place at an interval of 24 bars. Canons and fugues are in abundance, amongst them a fugue in 5-4 by Catel. One exercise by Cherubini is without bars, and another by the same composer is headed 'Contrepoint rigoureux à cinq voix sur le Plaint Chant.' If these two collections of vocalizzi are studied and conquered, an amount of theoretical and practical knowledge, as well as control over the voice, will have been gained that will fulfil every possible requirement preparatory to acquaintance with the great operatic and oratorical works. Mention must not be omitted of Concone's useful Exercises, of more modest calibre, which have gained a large popularity throughout musical Europe; nor of those of Madame Marchesi-Graumann, which give a great deal of excellent work, and were highly approved by Rossini.[ H. C. D. ]

- ↑ As Arpeggiare means 'to play upon the harp,' Gorgheggiare means 'to play upon the throat,' or rather that part of the throat known as the larynx; in other words, to treat the voice for the time only as an instrument.

- ↑ The abbreviation 'Alla Va SSa' can hardly mean other than 'alla Vergine Santissima.' The a must be a mistake of the French printer. These abbreviations are alternated through the exercise with, farther on, 'Satila al celo,' 'Alla SSa Trinita,' and last of all 'co moti gloria Eterna.' The word 'Satila' must also be a mistake. A later edition has this phrase, 'Satila al colo,' and the other 'co moli gloria eterna.' This does not help to clear up the matter.

- ↑ Cherubini's Autograph Catalogue [see vol. 1. p. 343a] contains an immense number of Solfeggi written between the years 1822 and 1842, in his capacity of Director of the Conservatoire, for the Examinations of the Pupils of that Institution.