A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Sonata

SONATA. The history of the Sonata is the history of an attempt to cope with one of the most singular problems ever presented to the mind of man, and its solution is one of the most successful achievements of his artistic instincts. A Sonata is, as its name implies, a sound-piece, and a sound-piece alone: in its purest and most perfect examples, it is unexplained by title or text, and unassisted by voices; it is nothing but an unlimited concatenation of musical notes. Such notes have individually no significance; and even the simplest principles of their relative definition and juxtaposition, such as is necessary to make the most elementary music, had to be drawn from the inner self and the consciousness of things which belong to man's nature only, without the possibility of finding guidance or more than the crudest suggestion from the observation of things external. Yet the structural principles by which such unpromising materials become intelligible have been so ordered and developed by the unaided musical instinct of many successive generations of composers, as to render possible long works which not only penetrate and stir us in detail, but are in their entire mass direct, consistent, and convincing. Such works, in their completest and most severely abstract forms, are Sonatas.

The name seems to have been first adopted purely as the antithesis to Cantata, the musical piece that was sung. It begins to come into notice about the same time as that form of composition, soon after the era of the most marked revolution in music, which began at the end of the sixteenth century; when a band of enthusiasts, led by visionary ideals, unconsciously sowed the seed of true modern music in an attempt to wrest the monopoly of the art in its highest forms from the predominant influence of the church, and to make it serve for the expression of human feelings of more comprehensive range. At this time the possibilities of polyphony in its ecclesiastical forms may well have seemed almost exhausted, and men turned about to find new fields which should give scope for a greater number of workers. The nature of their speculations and the associations of the old order of things alike conspired to direct their attention first to Opera and Cantata, and here they had something to guide them; but for abstract instrumental music of the Sonata kind they had for a long time no clue. The first suggestion was clearly accidental. It appears probable that the excessive elaboration of the Madrigal led to the practice of accompanying the voice parts with viols; and from this the step is but short to leaving the viols by themselves and making a vague kind of chamber music without the voices. This appears to have been the source of the instrumental Canzonas which were written in tolerable numbers till some way into the eighteenth century. It does not appear that any distinct rules for their construction were recognised, but the examination of a large number, written at different periods from Frescobaldi to J. S. Bach, proves the uniform object of the composers to have been a lax kind of fugue, such as might have served in its main outlines for the vocal madrigals. Burney says the earliest examples of 'sonatas' he had been able to discover in his devoted enquiries were by Turini, published at Venice in 1624. His description of those he examined answers perfectly to the character of the canzonas, for, he says, they consist of one movement, in fugue and imitation throughout. Sonatas did not, however, rest long at this point of simplicity, but were destined very early to absorb material from other sources; and though the canzona kind of movement maintained its distinct position through many changes in its environment, and is still found in the Violin Sonatas of J. S. Bach, Handel and Porpora, the madrigal, which was its source, soon ceased to have direct influence upon three parts of the more complete structure. The suggestion for these came from the dance, and the newly-invented opera or dramatic cantata. The former had existed and made the chief staple of instrumental music for generations, but it requires to be well understood that its direct connection with dancing puts it out of the category of abstract music of the kind which was now obscurely germinating. The dances were understood through their relation with one order of dance motions. There would be the order of rhythmic motions which taken together was called a Branle, another that was called a Pavan, another a Gigue; and each dance-tune maintained the distinctive rhythm and style throughout. On the other hand, the radical principle of the Sonata, developed in the course of generations, is the compounding of a limitless variety of rhythms; and though isolated passages may be justly interpreted as representing gestures of an ideal dance kind, like that of the ancients, it is not through this association that the group of movements taken as a whole is understood, but by the disposition of such elements and others in relation to one another. This conception took time to develop, though it is curious how early composers began to perceive the radical difference between the Suite and the Sonata. Occasionally a doubt seems to be implied by confusing the names together or by actually calling a collection of dance-tunes a sonata; but it can hardly be questioned that from almost the earliest times, as is proved by a strong majority of cases, there was a sort of undefined presentiment that their developments lay along totally different paths. In the first attempts to form an aggregate of distinct movements, the composers had to take their forms where they could find them; and among these were the familiar dance-tunes, which for a long while held a prominent position in the heterogeneous group of movements, and were only in late times transmuted into the Scherzo which supplanted the Minuet and Trio in one case, and the Finale or Rondo, which ultimately took the place of the Gigue, or Chaconne, or other similar dance-forms as the last member of the group.

The third source, as above mentioned, was the drama, and from this two general ideas were derivable: one from the short passages of instrumental prelude or interlude, and the other from the vocal portions. Of these, the first was intelligible in the drama through its relation to some point in the story, but it also early attained to a crude condition of form which was equally available apart from the drama. The other produced at first the vaguest and most rhapsodical of all the movements, as the type taken was the irregular declamatory recitative which appears to have abounded in the early operas.

It is hardly likely that it will ever be ascertained who first experimented in sonatas of several distinct movements. Many composers are mentioned in different places as having contributed works of the kind, such as Farina, Cesti, Graziani, among Italians, Rosenmüller among Germans, and John Jenkins among Englishmen. Burney also mentions a Michael Angelo Rossi, whose date is given as from about 1620 to 1660. An Andante and Allegro by him, given in Pauer's Alte Meister, require notice parenthetically as presenting a curious puzzle, if the dates are correct and the authorship rightly attributed. Though belonging to a period considerably before Corelli, they show a state of form which certainly was not commonly realised till more than a hundred years later. The distribution of subject-matter and key, and the clearness with which they are distinguished, are like the works of the middle of the 18th rather than the 17th century, and they belong absolutely to the Sonata order, and the conscious style of the later period. But as these stand alone it is not safe to infer anything from them. The actual structure of large numbers of sonatas composed in different parts of Europe soon after this time, proves a tolerably clear consent as to the arrangement and quality of the movements. A fine vigorous example is a Sonata in C minor for violin and figured bass, by H. J. F. Biber, a German, said to have been first published in 1681. This consists of five movements in alternate slow and quick time. The first is an introductory Largo of contrapuntal character, with clear and consistent treatment in the fugally imitative manner; the second is a Passacaglia, which answers roughly to a continuous string of variations on a short well-marked period; the third is a rhapsodical movement consisting of interspersed portions of Poco lento, Presto, and Adagio, leading into a Gavotte; and the last is a further rhapsodical movement alternating Adagio and Allegro. In this group the influence of the madrigal or canzona happens to be absent; the derivation of the movements being—in the first the contrapuntalism of the music of the church, in the second and fourth, dances, and in the third and fifth probably operatic or dramatic declamation. The work is essentially a violin sonata with accompaniment, and the violin-part points to the extraordinarily rapid advance to mastery which was made in the few years after its being accepted as an instrument fit for high-class music. The writing for the instrument is decidedly elaborate and difficult, especially in the double stops and contrapuntal passages which were much in vogue with almost all composers from this time till J. S. Bach. In the structure of the movements the fugal influences are most apparent, and there are very few signs of the systematic repetition of subjects in connection with well-marked distribution of keys, which in later times became indispensable.

Similar features and qualities are shown in the curious set of seveA Sonatas for Clavier by Johann Kuhnau, called 'Frische Clavier Früchte,' etc., of a little later date; but there are also in some parts indications of an awakening sense of the relation and balance of keys. The grouping of the movements is similar to those of Biber, though not identical; thus the first three have five movements or divisions, and the remainder four. There are examples of the same kind of rhapsodical slow movements, as may be seen in the Sonata (No. 2 of the set) which is given in Pauer's Alte Meister; there are several fugal movements, some of them clearly and musically written; and there are some good illustrations of dance types, as in the last movement of No. 3, and the Ciaccona of No. 6. But more important for the thread of continuous development are the peculiar attempts to balance tolerably defined and distinct subjects, and to distribute key and subject in large expanses, of which there are at least two clear examples. In a considerable proportion of the movements the most noticeable method of treatment is to alternate two characteristic groups of figures or subjects almost throughout, in different positions of the scale and at irregular intervals of time. This is illustrated in the first movement of the Sonata No. 2, in the first movement of No. 1, and in the third movement of No. 5. The subjects in the last of these are as follows:—

The point most worth notice is that the device lies half-way between fugue and true sonata-form. The alternation is like the recurrence of subject and countersubject in the former, wandering hazily in and out, and forwards and backwards, between nearly allied keys, as would be the case in a fugue. But the subjects are not presented in single parts or fugally answered. They enter and re-enter for the most part as concrete lumps of harmony, the harmonic accompaniment of the melody being taken as part of the idea; and this is essentially a quality of sonata-form. So the movements appear to hang midway between the two radically distinct domains of form; and while deriving most of their disposition from the older manners, they look forward, though obscurely, in the direction of modern practices. How obscure the ideas of the time on the subject must have been, appears from the other point which has been mentioned above; which is, that in a few cases Kuhnau has hit upon clear outlines of tonal form. In the second Sonata, for instance, there are two Arias, as they are called. They do not correspond in the least with modern notions of an aria any more than do the rare examples in Bach's and Handel's Suites. The first is a little complete piece of sixteen bars, divided exactly into halves by a double bar, with repeats after the familiar manner. The first half begins in F and ends in C, the second half goes as far as D minor and back, to conclude in F again. The subject-matter is irregularly distributed in the parts, and does not make any pretence of coinciding with the tonal divisions. The second Aria is on a different plan, and is one of the extremely rare examples in this early period of clear coincidence between subject and key. It is in the form which is often perversely misnamed 'lied-form,' which will in this place be called 'primary form' to avoid circumlocution and waste of space. It consists of twenty bars in D minor representing one distinct idea, complete with close: then sixteen bars devoted to a different subject, beginning in B♭ and passing back ultimately to D minor, recapitulating the whole of the first twenty bars in that key, and emphasising the close by repeating the last four bars. Such decisiveness, when compared with the unregulated and unbalanced wandering of longer movements, either points to the conclusion that composers did not realise the desirableness of balance in coincident ranges of subject and key on. a large scale; or that they were only capable of feeling it in short and easily grasped movements. It seems highly probable that their minds, being projected towards the kind of distribution of subject which obtained in fugal movements, were not on the lookout for effects of the sonata order which to moderns appear so obvious. So that, even if they had been capable of realising them more systematically they would not yet have thought it worth while to apply their knowledge. In following the development of Sonata, it ought never to be forgotten that composers had no idea whither they were tending, and had to use what they did know as stepping-stones to the unknown. In art, each step that is gained opens a fresh vista; but often, till the new position is mastered, what lies beyond is completely hidden and undreamed of. In fact, each step is not so much a conquest of new land, as the creation of a new mental or emotional position in the human organism. The achievements of art are the unravellings of hidden possibilities of abstract law, through the constant and cumulative extension of instincts. They do not actually exist till man has made them; they are the counterpart of his internal conditions, and change and develop with the changes of his mental powers and sensitive qualities, and apart from him have no validity. There is no such thing as leaping across a chasm on to a new continent, neither is there any gulf fixed anywhere, but continuity and inevitable antecedents to every consequent; the roots of the greatest masterpieces of modern times lie obscurely hidden in the wild dances and barbarous howlings of the remotest ancestors of the race, who began to take pleasure in rhythm and sound, and every step was into the unknown, or it may be better said not only unknown but non-existent till made by mental effort. The period from about 1600 to about 1725 contains the very difficult steps which led from the style appropriate to a high order of vocal music—of which the manner of speech is polyphonic, and the ideal type of form, the fugue—to the style appropriate to abstract instrumental music, of which the best manner is contrapuntally expressed harmony, and the ideal type of form, the Sonata. These works of Kuhnau's happen to illustrate very curiously the transition in which a true though crude idea of abstract music seems to have been present in the composer's mind, at the same time that his distribution of subjects and keys was almost invariably governed by fugal habits of thinking, even where the statement of subjects is in a harmonic manner. In some of these respects he is nearer and in some further back from the true solution of the problem than his famous contemporary Corelli; but his labours do not extend over so much space nor had they so much direct and widespread influence. In manner and distribution of movements they are nearer to his predecessor and compatriot Biber; and for that reason, and also to maintain the continuity of the historic development after Corelli, the consideration of his works has been taken a little before their actual place in point of time.

The works of Corelli form one of the most familiar landmarks in the history of music, and as they are exclusively instrumental it is clear that careful consideration ought to elicit a great deal of interesting matter, such as must throw valuable light on the state of thought of his time. He published no less than sixty sonatas of different kinds, which are divisible into distinct groups in accordance with purpose or construction. The first main division is that suggested by their titles. There are twenty-four 'Sonate da Chiesa' for strings, lute, and organ, twenty-four 'Sonate da Camera' for the same instruments, and twelve Solos or Sonatas for violin and violoncello, or 'cembalo.' In these the first and simplest matter for observation is the distribution of the movements. The average, in Church and Chamber Sonatas alike, is strongly in favour of four, beginning with a slow movement, and alternating the rest. There is also an attempt at balance in the alternation of character between the movements. The first is commonly in 4-time, of dignified and solid character, and generally aiming less at musical expression than the later movements. The second movement in the Church Sonata is freely fugal, in fact the exact type above described as a Canzona; the style is commonly rather dry, and the general effect chiefly a complacent kind of easy swing such as is familiar in most of Handel's fugues. In the Chamber Sonatas the character of the second movement is rather more variable; in some it is an Allemande, which, being dignified and solid, is a fair counterpart to the Canzona in the other Sonatas: sometimes it is a Courante, which is of lighter character. The third movement is the only one which is ever in a different key from the first and last. It is generally a characteristic one, in which other early composers of instrumental music, as well as Corelli, clearly endeavoured to infuse a certain amount of vague and tender sentiment. The most common time is 3-2. The extent of the movement is always limited, and the style, though simply contrapuntal in fact, seems to be ordered with a view to obtain smooth harmonious full-chord effects, as a contrast to the brusqueness of the preceding fugal movement. There is generally a certain amount of imitation between the parts, irregularly and fancifully disposed, but almost always avoiding the sounding of a single part alone. In the Chamber Sonatas, as might be anticipated, the third movement is frequently a Sarabande, though by no means always; for the same kind of slow movement as that in the Church Sonatas is sometimes adopted, as in the third Sonata of the Opera Seconda, which is as good an example of that class as could be taken. The last movement is almost invariably of a lively character in Church and Chamber Sonatas alike. In the latter, Gigas and Gavottes predominate, the character of which is so familiar that they need no description. The last movements in the Church Sonatas are of a similar vivacity and sprightliness, and sometimes so like in character and rhythm as to be hardly distinguishable from dance-tunes, except by the absence of the defining name and the double bar in the middle, and the repeats which are almost inevitable in the dance movements. This general scheme is occasionally varied without material difference of principle by the interpolation of an extra quick movement, as in the first six Sonatas of the Opera Quinta; in which it is a sort of show movement for the violin in a 'Moto continuo' style, added before or after the central slow movement. In a few cases the number is reduced to three by dropping the slow prelude, and in a few others the order is unsystematisable.

In accordance with the principles of classification above defined, the Church Sonatas appear to be much more strictly abstract than those for Chamber. The latter are, in many cases, not distinguishable from Suites. The Sonatas of Opera Quinta are variable. Thus the attractive Sonata in E minor, No. 8, is quite in the recognised suite-manner. Some are like the Sonate da Chiesa, and some are types of the mixed order more universally accepted later, having several undefined movements, together with one dance. The actual structure of the individual movements is most uncertain. Corelli clearly felt that something outside the domain of the fugal tribe was to be attained, but he had no notion of strict outlines of procedure. One thing which hampered him and other composers of the early times of instrumental music was their unwillingness to accept formal tunes as an element in their order of art. They had existed in popular song and dance music for certainly a century, and probably much more; but the idea of adopting them in high-class music was not yet in favour. Corelli occasionally produces one, but the fact that they generally occur with him in Gigas, which are the freest and least responsible portion of the Sonata, supports the inference that they were not yet regarded as worthy of general acceptance even if realised as an admissible element, but could only be smuggled-in in the least respectable movement with an implied smile to disarm criticism. Whether this was decisively so or not, the fact remains that till long after Corelli's time the conventional tune element was conspicuously absent from instrumental compositions. Hence the structural principles which to a modern seem almost inevitable were very nearly impracticable, or at all events unsuitable to the general principles of the music of that date. A modern expects the opening bars of a movement to present its most important subject, and he anticipates its repetition in the latter portion of the movement as a really vital part of form of any kind. But association and common sense were alike against such a usage being universal in Corelli's time. The associations of ecclesiastical and other serious vocal music, which were then preponderant to a supreme degree, were against strongly salient points, or strongly marked interest in short portions of a movement in contrast to parts of comparative unimportance. Consequently the opening bars of a movement would not be expected to stand out in sufficiently strong relief to be remembered unless they were repeated at once, as they would be in fugue. Human nature is against it. For not only does the mind take time to be wrought up to a fully receptive condition, unless the beginning is most exceptionally striking, but what comes after is likely to obliterate the impression made by it. As a matter of fact, if all things were equal, the portion most likely to remain in the mind of an average listener, is that immediately preceding the strongest cadences or conclusions of the paragraphs of the movement. It is true, composers do not argue in this manner, but they feel such things vaguely or instinctively, and generally with more sureness and justice than the cold-blooded argumentation of a theorist could attain to. Many examples in other early composers besides Corelli, emphasise this point effectively. The earliest attempts at structural form must inevitably present some simply explicable principle of this sort, which is only not trivial because it is a very significant as well as indispensable starting-point. Corelli's commonest devices of form are the most unsophisticated applications of such simple reasoning. In the first place, in many movements which are not fugal, the opening bars are immediately repeated in another position in the scale, simply and without periphrasis, as if to give the listener assurance of an idea of balance at the very outset. That he did this to a certain extent consciously, is obvious from his having employed the device in at least the following Sonatas—2, 3, 8, 9, 10, 11, of Opera 1ma; 2, 4, 7, 8, of Opera 3za; and 2, 4, 5, and 11, of Opera 4ta; and Tartini and other composers of the same school followed his lead. This device is not however either so conspicuous or so common as that of repeating the concluding passage of the first half at the end of the whole, or of the concluding passages of one half or both consecutively. This, however, was not restricted to Corelli, but is found in the works of most composers from his time to Scarlatti, J. S. Bach and his sons; and it is no extravagant hypothesis that its gradual extension was the direct origin of the characteristic second section and second subject of modern sonata movements. In many cases it is the only element of form, in the modern sense, in Corelli's movements. In a few cases he hit upon more complicated principles. The Corrente in Sonata 5 of Opera 4ta, is nearly a miniature of modern binary form. The well-known Giga in A in the fifth Sonata of Opera 5ta, has balance of key in the first half of the movement, modulation, and something like consistency to subject-matter at the beginning of the second half, and due recapitulation of principal subject-matter at the end. The last movement of the eighth Sonata of the Opera Terza, is within reasonable distance of rondo-form, though this form is generally as conspicuous for its absence in early sonatas as tunes are, and probably the one follows as a natural consequence of the other. Of the simple primary form, consisting of corresponding beginning and end, and contrast of some sort in the middle, there is singularly little. The clearest example is probably the Tempo di Gavotta, which concludes the ninth Sonata of Opera Quinta. He also supplies suggestions of the earliest types of Sonata form, in which both the beginnings and endings of each half of the movement correspond; as this became an accepted principle of structure with later composers, it will have to be considered more fully in relation to their works. Of devices of form which belong to the great polyphonic tribe, Corelli uses many, but with more musical feeling than learning. His fugues are not remarkable as fugues, and he uses contrapuntal imitation rather as a subordinate means of carrying on the interest, than of expounding any wonderful device of pedantic wisdom, as was too common in those days. He makes good use of the chaconne-form, which was a great favourite with the early composers, and also uses the kindred device of carrying the repetition of a short figure through the greater part of a movement in different phases and positions of the scale. In some cases he merely rambles on without any perceptible aim whatever, only keeping up an equable flow of sound with pleasant interfacings of easy counterpoint, led on from moment to moment by suspensions and occasional imitation, and here and there a helpful sequence. Corelli's position as a composer is inseparably mixed up with his position as one of the earliest masters of his instrument. His style of writing for it does not appear to be so elaborate as other contemporaries, both older and younger, but he grasped a just way of expressing things with it, and for the most part the fit things to say. The impression he made upon musical people in all parts of the musical world was strong, and he was long regarded as the most delightful of composers in his particular line; and though the professors of his day did not always hold him in so high estimation, his influence upon many of his most distinguished successors was unquestionably powerful.

It is possible, however, that appearances are deceptive, and that influences of which he was only the most familiar exponent, are mistaken for his peculiar achievement. Thus knowing his position at the head of a great school of violinists, which continued through several generations down to Haydn's time, it is difficult to disunite him from the honour of having fixed the type of sonata which they almost uniformly adopted. And not only this noble and vigorous school, comprising such men as Tartini, Vivaldi, Locatelli, Nardini, Veracini, and outlying members like Léclair and Rust, but men who were not specially attached to their violins, such as Albinoni and Purcell, and later, Bach, Handel and Porpora, equally adopted the type. Of Albinoni not much seems to be distinctly known, except that he was Corelli's contemporary and probably junior. He wrote operas and instrumental music. Of the latter, several sonatas are still to be seen, but they are, of course, not familiar, though at one time they enjoyed a wide popularity. The chief point about them is that in many for violin and figured bass he follows not only the same general outlines, but even the style of Corelli. He adopts the four-movement plan, with a decided canzona in the second place, a slow movement first and third, and a quick movement to end with, such as in one case a Corrente. Purcell's having followed Corelli's lead is repudiated by enthusiasts; but at all events the lines of his Golden Sonata in F are wonderfully similar. There are three slow movements, which come first, second, and fourth; the third movement is actually called a Canzona; and the last is a quick movement in 3-8 time, similar in style to corresponding portions of Corelli's Sonatas. The second movement, an Adagio, is the most expressive, being happily devised on the principle above referred to, of repeating a short figure in different positions throughout the movement. In respect of sonata-form the work is about on a par with the average of Corelli or Biber.

The domain of Sonata was for a long while almost monopolised by violinists and writers for the violin. Some of these, such as Geminiani and Locatelli, were actually Corelli's pupils. They clearly followed him both in style and structural outlines, but they also began to extend and build upon them with remarkable speed. The second movement continued for long the most stationary and conventional, maintaining the Canzona type in a loose fugal manner, by the side of remarkable changes in the other movements. Of these the first began to grow into larger dimensions and clearer proportions even in Corelli's own later works, attaining to the dignity of double bars and repeats, and with his successors to a consistent and self-sufficing form. An example of this is the admirable Larghetto affettuoso with which Tartini's celebrated 'Trillo del Diavolo' commences. No one who has heard it could fail to be struck with the force of the simple device above described of making the ends of each half correspond, as the passage is made to stand out from all the rest more characteristically than usual. A similar and very good example is the introductory Largo to the Sonata in G minor, for violin and figured bass, by Locatelli, which is given in Ferdinand David's 'Hohe Schule des Violinspiels.' The subject-matter in both examples is exceedingly well handled, so that a sense of perfect consistency is maintained without concrete repetition of subjects, except, as already noticed, the closing bars of each half, which in Locatelli's Sonata are rendered less obvious through the addition of a short coda starting from a happy interrupted cadence. It is out of the question to follow the variety of aspects presented by the introductory slow movement; a fair proportion are on similar lines to the above examples, others are isolated. Their character is almost uniformly solid and large; they are often expressive, but generally in a way distinct from the character of the second slow movement, which from the first was chosen as the fittest to admit a vein of tenderer sentiment. The most important matter in the history of the Sonata at this period is the rapidity with which advance was made towards the realisation of modern harmonic and tonal principles of structure, or, in other words, the perception of the effect and significance of relations between chords and distinct keys, and consequent appearance of regularity of purpose in the distribution of both, and increased freedom of modulation. Even Corelli's own pupils show consistent form of the sonata kind with remarkable clearness. The last movement of a Sonata in C minor, by Geminiani, has a clear and emphatic subject to start with; modulation to the relative major, E♭, and special features to characterise the second section; and conclusion of the first half in that key, with repeat after the supposed orthodox manner. The second half begins with a long section corresponding to the working out or 'free fantasia' portion of a modern sonata movement, and concludes with recapitulation of the first subject and chief features of the second section in C minor; this latter part differing chiefly from modern ways by admitting a certain amount of discursiveness, which is characteristic of most of the early experiments in this form. Similar to this is the last movement of Locatelli's Sonata in G minor, the last movement of Veracini's Sonata in E minor, published at Vienna in 1714, the last movements of Tartini's Sonatas in E minor and D minor, and not a few others. It is rather curious that most of the early examples of what is sometimes called first-movement form are last movements. Most of these movements, however, in the early times, are distinguished by a peculiarity which is of some importance. It has been before referred to, but is so characteristic of the process of growth, that it will not be amiss to describe it in this place. The simple and almost homely means of producing the effect of structural balance by making the beginning and ending of each half of a movement correspond, is not so conspicuously common in its entirety as the correspondence of endings or repetition of cadence bars only; but it nevertheless is found tolerably often, and that in times before the virtue of a balance of keys in the first half of the movement had been decisively realised. When, however, this point was gained, it is clear that such a process would give, on as minute a scale as possible, the very next thing to complete modern binary form. It only needed to expand the opening passage into a first subject, and the figures of the Cadence into a second subject, to attain that type which became almost universal in sonatas till Haydn's time, and with some second-rate composers, like Reichart, later. The movements which are described as binary must be therefore divided into two distinct classes:—that in which the first subject reappears in the complementary key at the beginning of the second half, which is the almost universal type of earlier times; and that in which it appears in the latter part of the movement, after the working-out portion, which is the later type. The experiments in Corelli and Tartini, and others who are close to these types, are endless. Sometimes there are tentative strokes near to the later form; sometimes there is an inverted order reproducing the second portion of the movement first. Sometimes the first subject makes its appearance at both points, but then, may be, there is no balance of keys in the first half, and so forth. The variety is extraordinary, and it is most interesting to watch the manner in which some types by degrees preponderate, sometimes by combining with one another, sometimes by gradual transformation, come nearer and more decisively like the types which are generally adopted in modern times as fittest. The later type was not decisively fixed on at any particular point, for many early composers touched it once or twice at the same period that they were writing movements in more elementary forms. The point of actual achievement of a step in art is not marked by an isolated instance, but by decisive preponderance, and by the systematic adoption which shows at least an instinctive realisation of its value and importance.

These writers of violin sonatas were just touching on the clear realisation of harmonic form as accepted in modern times, and they sometimes adopted the later type, though rarely, and that obscurely; they mastered the earlier type, and used it freely; and they also used the intermediate type which combines the two, in which the principal or first subject makes its appearance both at the beginning of the first half and near the end, where a modern would expect it. As a sort of embryonic suggestion of this, the Tempo di Gavotta, in the eighth Sonata of Corelli's Opera Seconda, is significant. Complete examples are—the last movement of Tartini's fourth Sonata of Opus 1, and the last movement of that in D minor above referred to; the last movement of Geminiani's Sonata in C minor; the main portion, excluding the Coda, of the Corrente in Vivaldi's Sonata in A major; the last movement of a Sonata of Nardini's, in D major; and two Capriccios in B♭ and C, by Franz Benda, quoted in F. David's 'Hohe Schule,' etc.

The four-movement type of violin sonata was not invariably adopted, though it preponderates so conspicuously. There is a set of twelve sonatas by Locatelli, for instance, not so fine as that in F. David's collection, which are nearly all on an original three-movement plan, concluding with an 'Aria' and variations on a ground-bass. Some of Tartini's are also in three movements, and a set of six by Nardini are also in three, but always beginning with a slow movement, and therefore, though almost of the same date, not really approaching the distribution commonly adopted by Haydn for Clavier Sonatas. In fact the old Violin Sonata is in many respects a distinct genus, which maintained its individuality alongside the gradually stereotyped Clavier Sonata, and only ceased when that type obtained possession of the field, and the violin was reintroduced, at first as it were furtively, as an accompaniment to the pianoforte. The general characteristics of this school of writers for the violin, were nobility of style and richness of feeling, an astonishing mastery of the instrument, and a rapidly-growing facility in dealing with structure in respect of subject, key, modulation and development; and what is most vital, though less obvious, a perceptible growth in the art of expression and a progress towards the definition of ideas. As a set-off there are occasional traces of pedantic manners, and occasional crudities both of structure and expression, derived probably from the associations of the old music which they had so lately left behind them. At the crown of the edifice are the Sonatas of J. S. Bach. Of sonatas in general he appears not to have held to any decisive opinion. He wrote many for various instruments, and for various combinations of instruments. For clavier, for violin alone, for flute, violin, and clavier, for viol da gamba and clavier, and so on; but in most of these the outlines are not decisively distinct from Suites. In some cases the works are described as 'Sonatas or Suites,' and in at least one case the introduction to a church cantata is called a Sonata. Some instrumental works which are called Sonatas only, might quite as well be called Suites, as they consist of a prelude and a set of dance-tunes. Others are heterogeneous. From this it appears that he had not satisfied himself on what lines to attack the Sonata in any sense approaching the modern idea. With the Violin Sonatas it was otherwise; and in the group of six for violin and clavier he follows almost invariably the main outlines which are characteristic of the Italian school descended from Corelli, and all but one are on the four-movement plan, having slow movements first and third, and quick movements second and fourth. The sixth Sonata only differs from the rest by having an additional quick movement at the beginning. Not only this but the second movements keep decisively the formal lineaments of the ancient type of free fugue, illustrated with more strictness of manner by the Canzonas. Only in calibre and quality of ideas, and in some peculiar idiosyncrasies of structure do they differ materially from the works of the Italian masters. Even the first, third, and fifth Sonatas in the other set of six, for violin alone, conform accurately to the old four-movement plan, including the fugue in the second place; the remaining three being on the general lines of the Suite. In most of the Sonatas for violin and clavier, the slow movement is a tower of strength, and strikes a point of rich and complex emotional expression which music reached for the first time in Bach's imagination. His favourite way of formulating a movement of this sort, was to develop the whole accompaniment consistently on a concise and strongly-marked figure, which by repetition in different conditions formed a bond of connection throughout the whole; and on this he built a passionate kind of recitative, a free and unconstrained outpouring of the deepest and noblest instrumental song. This was a sort of apotheosis of that form of rhapsody, which has been noticed in the early Sonatas, such as Biber's and Kuhnau's, and was occasionally attempted by the Italians. The six Sonatas present diversities of types, all of the loftiest order; some of them combining together with unfailing expressiveness perfect specimens of old forms of contrapuntal ingenuity. Of this, the second movement of the second Sonata is a perfect example. It appears to be a pathetic colloquy between the violin and the treble of the clavier part, to which the bass keeps up the slow constant motion of staccato semiquavers: the colloquy at the same time is in strict canon throughout, and, as a specimen of expressive treatment of that time-honoured form, is almost unrivalled.

In all these movements the kinship is rather with the contrapuntal writers of the past, than with the types of Beethoven's adoption. Even Bach, immense as his genius and power of divination was, could not leap over that period of formation which it seems to have been indispensable for mankind to pass through, before equally noble and deeply-felt things could be expressed in the characteristically modern manner. Though he looked further into the future in matters of expression and harmonic combination than any composer till the present century, he still had to use forms of the contrapuntal and fugal order for the expression of his highest thoughts. He did occasionally make use of binary form, though not in these Sonatas. But he more commonly adopted, and combined with more or less fugal treatment, an expansion of simple primary form to attain structural effect. Thus, in the second movements of the first and second Sonatas, in the last of the third and sixth, and the first of the sixth, he marks first a long complete section in his principal key, then takes his way into modulations and development, and discussion of themes and various kinds of contrapuntal enjoyment, and concludes with simple complete recapitulation of the first section in the principal key. Bach thus stands singularly aside from the direct line of the development of the Sonata as far as the structural elements are concerned. His contributions to the art of expression, to the development of resource, and to the definition and treatment of ideas had great effect, and are of the very highest importance to instrumental music; but his almost invariable choice of either the suite-form, or the accepted outlines of the violin sonata, in works of this class, caused him to diverge into a course which with him found its final and supreme limit. In order to continue the work in veins which were yet unexhausted, the path had to be turned a little, and joined to courses which were coming up from other directions. The violin sonata continued to make its appearance here and there as has already been mentioned, but in the course of a generation it was entirely supplanted by the distinct type of clavier sonata.

Meanwhile there was another composer of this time, who appears to stand just as singularly apart from the direct high road as Bach, and who, though he does not occupy a pedestal so high in the history of art, still has a niche by no means low or inconspicuous, and one which he shares with no one. Domenico Scarlatti was Bach's senior by a few years, though not enough to place him in an earlier musical generation; and in fact though his works are so different in quality, they have the stamp that marks them as belonging to the same parallel of time.

His most valuable contributions are in the immense number of sonatas and studies which he wrote for the harpsichord. The distinction between Study and Sonata is not clearly marked with him; it looks as if one included the other in most cases, for the structure and style vary very little, and not necessarily or systematically at all, between one and the other. But whatever they are called they do not correspond in appearance to any form which is commonly supposed to be essential to the Sonata. Neither can they be taken as pure-bred members of the fugal family, nor do they trace their origins to the Suite. They are in fact, in a fair proportion of cases, an attempt to deal with direct ideas in a modern sense, without appealing to the glamour of conscious association, the dignity of science, or the familiarity of established dance rhythms. The connection with what goes before and with what comes after is alike obscure, because of the daring originality with which existing materials are worked upon; but it is not the less inevitably present, as an outline of his structural principles will show.

His utterance is at its best sharp and incisive; the form in which he loves to express himself is epigrammatic; and some of his most effective sonatas are like strings of short propositions bound together by an indefinable sense of consistency and consequence, rather than by actual development. These ideas are commonly brought home to the hearer by the singular practice of repeating them consecutively as they stand, often several times over; in respect of which it is worth remembering that his position in relation to his audience was not unlike that of an orator addressing an uncultivated mob. The capacity for appreciating grand developments of structure was as undeveloped in them as the power of following widely-spread argument and conclusion would be in the mob. And just as the mob-orator makes his most powerful impressions by short direct statements, and by hammering them in while still hot from his lips, so Scarlatti drove his points home by frequent and generally identical reiterations; and then when the time came round to refer to them again, the force of the connection between distant parts of the same story was more easily grasped. The feeling that he did this with his eyes open is strengthened by the fact that even in the grouping of the reiterations there is commonly a perceptible method. For instance, it can hardly be by accident that at a certain point of the movement, after several simple repetitions, he should frequently resort to the complication of repeating several small groups within the repetition of large ones. The following example is a happy illustration of his style, and of his way of elaborating such repetitions.

![{ << \new Staff = "up" \relative d''' { \time 3/8 \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key g \major

\stemUp r8 d a ~ |

\repeat unfold 2 { \[ a8 cis16 a a a | a8 fis a ~ \] }

\[ a8 cis16 a a a | a8 fis16 g a fis \] | g e fis d e cis | %eol2

d4 a8 ~ |

\repeat unfold 2 { \[ a8 cis16 a a a | a8 fis a ~ \] }

\[ a8 cis16 a a a | a8 fis16 g a fis \] | g e fis d e cis_"etc." }

\new Staff = "down" \relative d { \key g \major \clef bass

\repeat unfold 3 { d16 \change Staff = "up" d' fis a fis d |

\change Staff = "down" a, a' cis e cis a }

d,8 e fis | g a a, | %end line 2

\repeat unfold 3 { d,16 d' fis a fis d | a a' cis e cis a }

d,8 e fis | g a a, } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/4/s4oi6vw7mkbdznsl9vlfvfzy22mhvrt/s4oi6vw7.png)

It must not be supposed that he makes a law of this procedure, but the remarkably frequent occurrence of so curious a device is certainly suggestive of conscious purpose in structural treatment. The result of this mode is that the movements often appear to be crowded with ideas. Commonly the features of the opening bars, which in modern times would be held of almost supreme importance, serve for very little except to determine the character of the movement, and often never make their appearance again. On the other hand he carries the practice before referred to, of making the latter part of each half of the movement correspond, to an extraordinary pitch, and with perfect success; for he almost invariably adopts the key distribution of binary form in its main outlines; and though it would not be accurate to speak of such a thing as a 'second subject' in his sonatas, the impression produced by his distribution of repetition and the clearness of his ideas is sufficient, in his best movements, to give a general structural effect very similar to complete binary form on a small scale. In order to realise to what extent the process of recapitulation is carried by him, it will be as well to consider the outline of a fairly characteristic sonata. That which stands fifteenth in the easily available edition of Breitkopf & Härtel commences with eight bars only in E minor; the next forty-six, barring merely a slight and unimportant digression, are in G major. This concludes the first half. The second half begins with reference to the opening figures of the whole and a little key digression, and then a characteristic portion of the second section of the first half is resumed, and the last thirty-four bars of the movement are a recapitulation in E minor of the last thirty-five of the first half, the three concluding bars being condensed into two.

In many respects his principles of structure and treatment are altogether in the direction of modern ways, and alien to fugal principles. That vital principle of the fugue—the persistence of one principal idea, and the interweaving of it into every part of the structure—appears completely alien to Scarlatti's disposition. He very rarely wrote a fugue; and when he did, if it was successful that was less because it was a good fugue than because it was Scarlatti's. The fact that he often starts with imitation between two parts is unimportant, and the merest accident of association. He generally treats his ideas as concrete lumps, and disposes them in distinct portions of the movement, which is essentially an unfugal proceeding; but the most important matter is that he was probably the first to attain to clear conception and treatment of a self-sufficing effective idea, and to use it, if without science, yet with management which is often convincingly successful. He was not a great master of the art of composition, but he was one of the rarest masters of his instrument; and his divination of the way to treat it, and the perfect adaptation of his ideas to its requirements, more than counterbalance any shortcoming in his science. He was blessed with ideas, and with a style so essentially his own, that even when his music is transported to another instrument the characteristic effects of tone often remain unmistakeable. Vivacity, humour, genuine fun, are his most familiar traits. At his best his music sparkles with life and freshness, and its vitality is apparently quite unimpaired by age. He rarely approaches tenderness or sadness, and in the whole mass of his works there are hardly any slow movements. He is not a little 'bohemian,' and seems positively to revel in curious effects of consecutive fifths and consecutive octaves. The characteristic daring of which such things are the most superficial manifestations, joined with the clearness of his foresight, made him of closer kinship to Beethoven and Weber, and even Brahms, than to the typical contrapuntalists of his day. His works are genuine 'sonatas' in the most radical sense of the term—self-dependent and self-sufficing sound-pieces, without programme. To this the distribution of movements is at least of secondary importance, and his confining himself to one alone does not vitiate his title to be a foremost contributor to that very important branch of the musical art. No successor was strong enough to wield his bow. His pupil Durante wrote some sonatas, consisting of a Studio and a Divertimento apiece, which have touches of his manner, but without sufficient of the nervous elasticity to make them important.

The contemporary writers for clavier of second rank do not offer much which is of high musical interest, and they certainly do not arrive at anything like the richness of thought and expression which is shown by their fellows of the violin. There appears however amongst them a tendency to drop the introductory slow movement characteristic of the violin sonata, and by that means to draw nearer to the type of later clavier or pianoforte sonatas. Thus a sonata of Wagenseil's in F major presents almost exactly the general outlines to be met with in Haydn's works—an Allegro assai in binary form of the old type, a short Andantino grazioso, and a Tempo di Minuetto. A sonata of Hasse's in D minor has a similar arrangement of three movements ending with a Gigue; but the first movement is utterly vague and indefinite in form. There is also an Allegro of Hasse's in B♭, quoted in Pauer's Alte Meister, which deserves consideration for the light it throws on a matter which is sometimes said to be a crucial distinction between the early attempts at form and the perfect achievement. In many of the early examples of sonata-form, the second section of the first part is characterised by groups of figures which are quite definite enough for all reasonable purposes, but do not come up to the ideas commonly entertained of the nature of a subject; and on this ground the settlement of sonata-form was deferred some fifty years. Hasse was not a daring originator, neither was he likely to strike upon a crucial test of perfection, yet in this movement he sets out with a distinct and complete subject in B♭ of a robust Handelian character:—

and after the usual extension proceeds to F, and announces by definite emphasis on the Dominant the well-contrasted second subject, which is suggestive of the polite reaction looming in the future:—

![{ << \new Staff \relative c'' { \key bes \major \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \partial 8

c8 | \repeat unfold 2 { f16 g a g f8 c g'16 a bes a g8 c, }

a'16 bes c bes a8 g16 f f e d c f8 <bes, g> | %end line 2

<< { a4 g8\trill f16 g f2 } \\ { f4 e f2 } >> | s4_"etc." }

\new Staff \relative b' { \key bes \major

bes8 | a4 r16 a g f e4 r16 c d e | f4 r16 a g f e4 r16 c d e |

f4 \clef bass r8 <d bes> <c g'>[ <bes e>] <a f'> <bes d> | %eol2

c4 c, f r | s } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/9/y/9yi3hrpnica1djjlx7knuru7zgs3wlm/9yi3hrpn.png)

The movement as a whole is in the binary type of the earlier kind.

The period now approaching is characterised by uncertainty in the distribution of the movements, but increasing regularity and definition in their internal structure. Some writers follow the four-movement type of violin sonata in writing for the clavier; some strike upon the grouping of three movements; and a good many fall back upon two. A sonata of Galuppi's in D illustrates the first of these, and throws light upon the transitional process. The first movement is a beautiful Adagio of the Arioso type, with the endings of each half corresponding, after the manner traced from Corelli; the second is an Allegro not of the fugal or Canzona order, but clear binary of the older kind. A violin sonata of Locatelli's, of probably earlier date, has an Allemande of excellent form in this position, but this is not sufficiently definite in the inference it affords to throw much light on any transition or assimilation of violin sonata-form to clavier sonata-form. Galuppi's adoption of a movement of clear sonata-qualities in this place supplies exactly the link that was needed; and the fugal or canzona type of movement being so supplanted, nothing further was necessary but expansion, and the omission of the introductory Adagio (which probably was not so well adapted to the earlier keyed instruments as to the violin), to arrive at the principle of distribution adopted in the palmiest days of formalism. Later, with a more powerful instrument, the introductory slow movement was often reintroduced. Galuppi's third movement is in a solid march style, and the last is a Giga. All of them are harmonically constructed, and the whole work is solid and of sterling musical worth.

Dr. Arne was born only four years after Galuppi, and was amenable to the same general influences. The structure of his sonatas emphasises the fact above mentioned, that though the order of movements was passing through a phase of uncertainty their internal structure was growing more and more distinct and uniform. His first sonata, in F, has two movements, Andante and Allegro, both of which follow harmonically the lines of binary form. The second, in E minor, has three movements, Andante, Adagio, Allegrissimo. The first and last are on the binary lines, and the middle one in simple primary form. The third Sonata consists of a long vague introduction of arpeggios, elaborated in a manner characteristic of the time, an Allegro which has only one subject but is on the binary lines, and a Minuet and two Variations. The fourth Sonata is in some respects the most interesting. It consists of an Andante, Siciliano, Fuga, and Allegro. The first is of continuous character but nevertheless in binary form, without the strong emphasis on the points of division between the sections. It deserves notice for its expressiveness and clearness of thought. The second movement is very short, but pretty and expressive, of a character similar to examples of Handel's tenderer moods. The last movement is particularly to be noticed, not only for being decisively in binary form, but for the ingenuity with which that form is manipulated. The first section is represented by the main subject in the treble, the second (which is clearly marked in the dominant key) has the same subject in the bass, a device adopted also more elaborately by W. Friedemann Bach. The second half begins with consistent development and modulation, and the recapitulation is happily managed by making the main subject represent both sections at once in a short passage of canon. Others of Arne's sonatas afford similar though less clear examples which it is superfluous to consider in detail, for neither the matter nor the handling is so good in them as in those above described, most of which, though not rich in thought or treatment, nor impressive in character, have genuine traits of musical expression and clearness of workmanship.

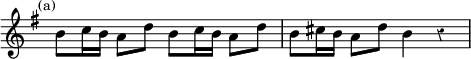

In the same year with Dr. Arne was born Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, the eldest son of John Sebastian. He was probably the most gifted, the most independent, and unfortunately the wildest and most unmanageable of that remarkable family. Few of his compositions are known, and it is said that he would not take the trouble to write unless he was driven to it. Two sonatas exist, which are of different type, and probably represent different periods of his chequered career. One in D major, for its richness, elaborateness, expressiveness, is well worthy of the scion of so great a stock; the other is rather cheap, and though masterly in handling and disposition of structural elements, has more traces of the elegance which was creeping over the world of music than of the grave and earnest nobleness of his father and similar representatives of the grand period. The first, in D, is probably the most remarkable example, before Beethoven, of original ingenuity manipulating sonata-form under the influence of fugal associations and by means of contrapuntal devices. The whole is worked out with careful and intelligible reasoning, but to such an elaborate extent that it is quite out of the question to give even a complete outline of its contents. The movements are three—Un poco allegro, Adagio, Vivace. The first and last are speculative experiments in binary form. The first half in each represents the balance of expository sections in tonic and complementary keys. The main subject of the first reappears in the bass in the second section, with a new phase of the original accompaniment in the upper parts. The development portion is in its usual place, but the recapitulation is tonally reversed. The first subject and section is given in a relative key to balance the complementary key of the second section, and the second section is given in the original key or tonic of the movement; so that instead of repeating one section and transposing the other in recapitulation, they are both transposed analogously. In each of the three movements the ends of the halves correspond, and not only this but the graceful little figure appended to the cadence is the same in all the movements, establishing thereby a very delicate but sensible connection between them. This figure is as follows:—

![{ << \new Staff \relative f' { \key d \major \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \mark \markup \small "(a)" \partial 4

<< { \grace fis8^( e4) | d8. a16 \tuplet 3/2 { b8 g' cis, } \acciaccatura cis8 d4 | s_"etc." } \\

{ \grace { \stemDown d8 } cis4 d8. } >> }

\new Staff \relative a { \key d \major \clef bass

<< { r16 a8 g16 | g8. fis16 g8.[ e16] \acciaccatura e8 fis4 | s } \\

{ a,4 | d2 _~ d4 } >> } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/h/d/hdiu67n7ujtwu6cndwh70wbktg2ooyk/hdiu67n7.png)

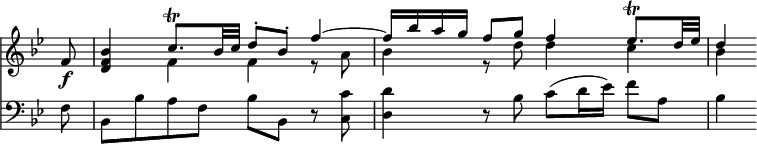

![{ << \new Staff = "up" \relative b { \key d \major \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \mark \markup \small "(b)" \clef bass

<< { b8 ~ \override TupletBracket.bracket-visibility = ##f \tuplet 3/2 8 { b16 fis a! \override TupletNumber #'stencil = ##f a[^\( g fis] g[ e' ais,]\) } \appoggiatura aes8 b4 | s_"etc." } \\

{ b8 \change Staff = "down" \stemUp dis, e4 ^~ e8 d } >> }

\new Staff = "down" \relative b, { \key d \major \clef bass

b2. s4 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/y/pyb8v5w8nb1zloz633rd8vhz8fy14w3/pyb8v5w8.png)

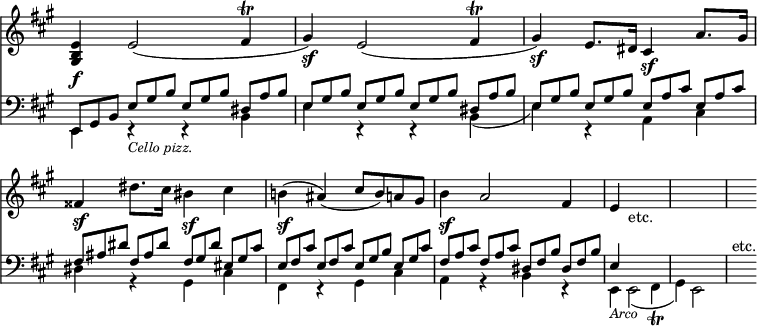

![{ << \new Staff \relative c' { \key d \major \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \time 3/4 \mark \markup \small "(c)" \partial 4 \override TupletNumber #'stencil = ##f

cis4\prall | \tuplet 3/2 4 { d8[ a c] b[ g' cis,] } d4 \bar "||" }

\new Staff \relative g { \key d \major \clef bass

<< { \override TupletNumber #'stencil = ##f g4 ~ \tuplet 3/2 4 { g8 fis a g e a } fis4 } \\

{ a,4 d2 d4 } >> } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/l/n/ln6e2oiwt1ild53qymi2u0ewcsj6vq7/ln6e2oiw.png)

The formal pauses on familiar points of harmony characteristic of later times are conspicuously few, the main divisions being generally marked by more subtle means. The whole sonata is so uncompromisingly full of expressive figures, and would require to be so elaborately phrased and 'sung' to be intelligible, that an adequate performance would be a matter of considerable difficulty. The second Sonata, in C, has quite a different appearance. It is also in three movements—Allegro, Grave, and Vivace. The first is a masterly, clear and concise example of binary form of the type which is more familiar in the works of Haydn and Mozart. The second is an unimportant intermezzo leading directly into the Finale, which is also in binary form of the composite type. The treatment is the very reverse of the previous sonata. It is not contrapuntal, nor fugal. Little pains are taken to make the details expressive; and the only result of using a bigger and less careful brush is to reduce the interest to a minimum, and to make the genuineness of the utterances seem doubtful, because the writer appears not to have taken the trouble to express his best thoughts.

Wilhelm Friedemann's brother, Carl Philip Emmanuel, his junior by a few years, was the member of the younger family who attained the highest reputation as a representative composer of instrumental music and a writer on that subject. His celebrity is more particularly based on the development of sonata-form, of which he is often spoken of as the inventor. True, his sonatas and writings obtained considerable celebrity, and familiarity induced people to remark things they had overlooked in the works of other composers. But in fact he is neither the inventor nor the establisher of sonata-form. It was understood before his day, both in details and in general distribution of movements. One type obtained the reputation of supreme fitness later, but it was not nearly always adopted by Haydn, nor invariably by Mozart, and was consistently departed from by Beethoven; and Emmanuel did not restrict himself to it; yet his predecessors used it often. It is evident therefore that his claims to a foremost place rest upon other grounds. Among these, most prominent is his comprehension and employment of the art of playing and expressing things on the clavier. He understood it, not in a new sense, but in one which was nearer to public comprehension than the treatment of his father. He grasped the phase to which it had arrived, by constant development in all quarters; he added a little of his own, and having a clear and ready-working brain, he brought it home to the musical public in a way they had not felt before. His influence was paramount to give a decided direction to clavier-playing, and it is possible that the style of which he was the foster-father passed on continuously to the masterly treatment of the pianoforte by Clementi, and through him to the culminating achievements of Beethoven.

In respect of structure, most of his important sonatas are in three movements, of which the first and last are quick, and the middle one slow; and this is a point by no means insignificant in the history of the sonata, as it represents a definite and characteristic balance between the principal divisions, in respect of style and expression as well as in the external traits of form. Many of these are in clear binary form, like those of his elder brother, and his admirable predecessor, yet to be noted, P. Domenico Paradies. He adopts sometimes the old type, dividing the recapitulation in the second half of the movement; sometimes the later, and sometimes the composite type. For the most part he is contented with the opportunities for variety which this form supplies, and casts a greater proportion of movements in it than most other composers, even to the extent of having all movements in a work in different phases of the same form, which in later times was rare. On the other hand, he occasionally experiments in structures as original as could well be devised. There is a Sonata in F minor which has three main divisions corresponding to movements. The first, an Allegro, approaches vaguely to binary form; the second, an Adagio, is in rough outline like simple primary form, concluding with a curious barless cadenza; the last is a Fantasia of the most elaborate and adventurous description, full of experiments in modulation, enharmonic and otherwise, changes of time, abrupt surprises and long passages entirely divested of bar lines. There is no definite subject, and no method in the distribution of keys. It is more like a rhapsodical improvisation of a most inconsequent and unconstrained description than the product of concentrated purpose, such as is generally expected in a sonata movement. This species of experiment has not survived in high-class modern music, except in the rarest cases. It was however not unfamiliar in those days, and superb examples in the same spirit were provided by John Sebastian, such as the Fantasia Cromatica, and parts of some of the Toccatas. John Ernst Bach also left something more after the manner of the present instance as the prelude to a fugue. Emmanuel Bach's position is particularly emphasised as the most prominent composer of sonatas of his time, who clearly shows the tendency of the new counter-current away from the vigour and honest comprehensiveness of the great school of which his father was the last and greatest representative, towards the elegance, polite ease, and artificiality, which became the almost indispensable conditions of the art in the latter part of the 18th century. Fortunately the process of propping up a tune upon a dummy accompaniment, was not yet accepted universally as a desirable phenomenon of high-class instrumental music; in fact such a stride downward in one generation would have been too cataclystic; so he was spared the temptation of shirking honest concentration, and padding his works, instead of making them thoroughly complete; and the result is a curious combination, sometimes savouring strongly of his father's style—

![{ << \new Staff \relative f'' { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key bes \major

<< { f4 e32[ d! e16 r16. g32] g4 ~ g16[ des c \tuplet 3/2 { bes32 aes g] } | g8 aes s s_"etc." } \\

{ g1 f4 } >> }

\new Staff \relative d' { \clef bass \key bes \major

<< { r16 des_( a c bes) fis_( aes g bes4) ^~ bes8 c } \\

{ s2 bes16 c,_( des c f8 e) } >> |

r16 f( c aes f8) } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/p/h/phqee50mqt1rxhewa0ce73lz5qf91yw/phqee50m.png)

and sometimes coldly predicting the style of the future—

In general, his building up of movements is full of expressive detail, and he does not spare himself trouble in enriching his work with such things as ingenuity, genuine musical perception and vivacity of thought can suggest. He occasionally reaches a point of tenderness and poetic sensibility which is not unworthy of his descent, but there is also sometimes an uncomfortable premonition in his slow movements of the posturing and posing which were soon to be almost inevitable in well-bred Adagios. The spirit is indeed not greatly deep and earnest, but in outward things the attainment of a rare degree of point and emphasis, and of clearness and certainty in construction without emptiness, sufficed to give Philip Emmanuel a foremost place among the craftsmen of the art.

P. Domenico Paradies was Emmanuel Bach's senior by a few years. Two of his sonatas, at least, are deservedly well known to musicians. The structural qualities shown by the whole set of twelve, emphasise the opinion that binary form was familiar to composers of this period. They differ from Philip Emmanuel's chiefly in consisting uniformly of two movements only. Of these, the first movements are almost invariably in binary form. That of the I st sonata is perfectly complete and of the later type; many of the others are of the early type. Some details in the distribution of the movements are worth noticing. Thus the last movement of No. 4 is a very graceful and pretty minuet, which had hitherto not been so common an ingredient in sonatas as it afterwards became. The last movement[1] of No. 3 is called an aria; the arrangement of parts of which, as well as that of the last movement of No. 9, happens to produce a rondo, hitherto an extremely rare feature. His formulation and arrangement of subjects is extremely clear and masterly, and thoroughly in the sonata manner—that is, essentially harmonical. In character he leans towards the style of the latter part of the 18th century, but has a grace and sincerity which is thoroughly his own. In a few cases, as in the last movements of the Sonatas in A and D, Nos. 6 and 10, which are probably best known of all, the character assumed is rather of the bustling and hearty type which is suggestive of the influence of Scarlatti. In detail they are not so rich as the best specimens of Emmanuel's, or of Friedemann Bach's workmanship; but they are thoroughly honest and genuine all through, and thoroughly musical, and show no sign of shuffling or laziness.

The two-movement form of clavier sonata, of which Paradies's are probably the best examples, seems to have been commonly adopted by a number of composers of second and lower rank, from his time till far on in the century. Those of Durante have been already mentioned. All the set of eight, by Domenico Alberti, are also in this form, and so are many by such forgotten contributors as Roeser and Barthelemon, and some by the once popular Schobert. Alberti is credited with the doubtful honour of having invented a formula of accompaniment which became a little too familiar in the course of the century, and is sometimes known as the 'Alberti Bass.' This specimen is from his 2nd Sonata.

He may not have invented it, but he certainly called as much attention to it as he could, since not one of his eight sonatas is without it, and in some movements it continues almost throughout. The movements approach occasionally to binary form, but are not clearly defined; the matter is for the most part dull in spirit, and poor in sound; and the strongest characteristic is the unfortunate one of hitting upon a cheap device, which was much in vogue with later composers of mark, without having arrived at that mastery and definition of form and subject which alone made it endurable. The times were not quite ripe for such usages, and it is fortunate for Paradies, who was slightly Alberti's junior, that he should have attained to a far better definition of structure without resorting to such cheapening.

There are two other composers of this period who deserve notice for maintaining, even later, some of the dignity and nobility of style which were now falling into neglect, together with clearness of structure and expressiveness of detail. These are Rolle and George Benda. A sonata of the former's in E♭ shows a less certain hand in the treatment of form, but at times extraordinary gleams of musically poetic feeling. Points in the Adagio are not unworthy of kinship with Beethoven. It contains broad and daring effects of modulation, and noble richness of sentiment and expression, which, by the side of the obvious tendencies of music in these days, is really astonishing. The first and last movements are in binary form of the old type, and contain some happy and musical strokes, though not so remarkable as the contents of the slow movement. George Benda was a younger and greater brother of the Franz who has been mentioned in connection with Violin Sonatas. He was one of the last writers who, using the now familiar forms, still retained some of the richness of the earlier manner. There is in his work much in the same tone and style as that of Emmanuel Bach, but also an earnestness and evident willingness to get the best out of himself and to deal with things in an original manner, such as was by this time becoming rare. After him, composers of anything short of first rank offer little to arrest attention either for individuality in treatment or earnestness of expression. The serious influences which had raised so many of the earlier composers to a point of memorable musical achievement were replaced by associations of far less genuine character, and the ease with which something could be constructed in the now familiar forms of sonata, seduced men into indolent uniformity of structure and commonplace prettiness in matter. Some attained to evident proficiency in the use of instrumental resource, such as Turini; and some to a touch of genuine though small expressiveness, as Haessler and Grazioli; for the rest the achievements of Sarti, Sacchini, Schobert, Méhul, and the otherwise great Cherubini, in the line of sonata, do not offer much that requires notice. They add nothing to the process of development, and some of them are remarkably behindhand in relation to their time, and both what they say and the manner of it is equally unimportant.