A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Spinet

SPINET (Fr. Épinette; Ital. Spinetta) [App. p.795 "After title add Fr. Epinette, Clavicorde; Ital. Spinetta, Clavicordo; Spanish Clavicordia. English Spinet, Virginal"]. A keyed instrument, with plectra or jacks, used in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries; according to Burney (Rees's Cycl. 1819, 'Harpsichord') 'a small harpsichord or virginal with one string to each note.' The following definitions are from Florio's 'New World of Words,' 1611:—'Spinetta, a kind of little spina … also a paire of Virginalles'; 'Spinettegiare, to play upon Virginalles'; 'Spinetto, a thicket of brambles or briars'—(see Rimbault's History of the Pianoforte, 1860). We first meet with the derivation of spinet from spina, a thorn, in Scaliger's Poetices (1484–1550; lib. i. cap. lxiii.). Referring to the plectra or jacks of keyed instruments, he says that, in his recollection, points of crowquill had been added to them, so that what was named, when he was a boy, 'clavicymbal' and 'harpichord' (sic), was now, from these little points, named 'spinet.' [See Jack.] He does not say what substance crowquill superseded, but we know that the old cithers and other wire-strung instruments were twanged with ivory, tortoiseshell, or hard wood.[1] Another origin for the name has been discovered, to which we believe that Signor Ponsicchi ('Il Pianoforte,' Florence, 1876) was the first to call attention. In a very rare book, 'Conclusioni nel suono dell' organo, di D. Adriano Banchieri, Bolognese' (Bologna, 1608), is this passage:—

Spinetta riceve tal nome dall' inventore di tal forma longa quadrata, il quale fù un maestro Giovanni Spinetti, Venetiano, ed uno di tali stromenti hò veduto io alle mani di Francesco Stivori, organista della magnifica comunità di Montagnana, dentrovi questa inscrizione: JOANNES SPINETUS VENETUS FECIT. A.D. 1503.

According to this the spinet received its name from Spinetti, a Venetian, the inventor of the oblong form, and Banchieri had himself seen one in the possession of Stivori, bearing the above inscription. M. Becker of Geneva ('Revue et Gazette musicale/ in the ' Musical World,' June 15, 1878), regards this statement as totally invalidating the passage from Scaliger; but not necessarily so, since the year 1503 is synchronous with the youth of Scaliger. The invention of the crowquill points is not claimed for Spinetti, but the form of the case—the oblong or table shape of the square piano and older clavichord, to which Spinetti adapted the plectrum instrument; it having previously been in a trapeze-shaped case, like the psaltery, from which, by the addition of a keyboard, the instrument was derived. [See Virginal; and also for the different construction and origin of the oblong clavichord.] Putting both statements together, we find the oblong form of the Italian spinet, and the crowquill plectra, in simultaneous use about the year 1500. Before that date no record has been found. The oldest German writers, Virdung and Arnold Schlick, whose essays appeared in 1511, do not mention the spinet, but Virdung describes and gives a woodcut of the Virginal, which in Italy would have been called at that time 'spinetta,' because it was an instrument with plectra in an oblong case. Spinetti's adaptation of the case had therefore travelled to Germany, and, as we shall presently see, to Flanders and Brabant, very early in the 16th century; whence M. Becker conjectures that 1503 represents a late date for Spinetti, and that we should put his invention back to the second half of the 15th century, on account of the time required for it to travel, and be accepted as a normal form in cities so remote from Venice.

[App. p.795 "Considerable light has been thrown upon the hitherto profoundly obscure invention of the keyboard instrument subsequently known as the Spinet, by that erudite search and scholar Mr. Edmond Vander Straeten, in 'La Musique aux Pays Bas,' vol. vii. (Les musiciens néerlandais en Espagne, 1re partie), Brussels, 1885. He quotes, p. 246, from a testamentary inventory of musical instruments which had belonged to Queen Isabella, at the Alcazar of Segovia, dated 1503. 'Dos Clavicinbanos viejos' that is to say, two old clavecins (spinets). One of her chamberlains, Sancho de Paredes (p. 248) owned in 1500 'Dos Clabiorganos'—two claviorgans or organized clavecins. In a previous inventory, dated 1480 (and earlier), the same chamberlain appears to have possessed a manicorde or clavichord with tangents. But Mr. Vander Straeten is enabled to give a positive date, 1387 (p. 40, et seq.), when John the First, King of Aragon, had heard and desired to possess an instrument called 'exaquir,' which was certainly a keyboard stringed-instrument. He describes it later on as resembling an organ but sounding with strings. The name 'exaquir' may be identified with 'l'eschuaqueil d'Angleterre,' which occurs in a poem entitled 'La Prise d'Alexandrie,' written by Guillaume de Machault, in the I4th century. Mr. Vander Straeten enquires if this appellation can be resolved by 'échiquier' (chequers) from the black and white arrangement of the keys? The name echiquier occurs in the romance 'Chevalier du cygne' and in the 'Chanson sur la journée de Guinegate,' a 15th century poem, in which the poet asks to be sounded

Orgius, harpes, naquaires, challemelles,

Bons echiquiers, guisternes, doucemelles.

The enquirer is referred to the continuance of Mr. Vander Straeten's notes on this interesting question, in the work above mentioned. It is here sufficient to be enabled to prove that a kind of organ sounding with strings was existing in 1387—and that clavecins were catalogued in 1503, that could be regarded as old; also that these dates synchronize with Ambros's earliest mention of the clavicymbalum, in a MS. of 1404."]

M. Vander Straeten ('La Musique aux Pays-Bas,' vol. i.) has discovered the following references to the spinet in the household accounts of Margaret of Austria:—

A ung organiste de la Ville d'Anvers, la somme da vi livres auqnel madicte dame en a fait don en faveur de ce que le xve jour d'Octobre xv.xxii [1522] il a amené deux jeunes enffans, filz et fille, qu'ils ont jouhé sur une espinette et chanté à son diner.

A l'organiste de Monsieur de Fiennes, sept livres dont Madame lui a fait don en faveur de ce que le second jour de Décembre xv.xxvi [1526] il est venu jouher d'un instrument dit espinette devant elle à son diner.

The inventory of the Château de Pont d'Ain, 1531, mentions 'una espinetta cum suo etuy,' a spinet with its case; meaning a case from which the instrument could be withdrawn, as was customary at that time. M. Becker transcribes also a contemporary reference from the Munich Library:—

Quartorze Gaillardes, neuf Pavannes, sept Bransles et deux Basses-Dances, le tout reduict de musique en la tablature du ieu (jeu) Dorgues, Espinettes, Manicordions et telz semblables instruments musicaux, imprimées à Paris par Pierre Attaignant MDXXIX.

The manichord was a clavichord. Clement Marot (Lyons, 1551) dedicated his version of the Psalms to his countrywomen:—

Et vos doigts sur les Espinettes,

Pour dire Saintes Chansonettes.

With this written testimony we have fortunately the testimony of the instruments themselves, Italian oblong spinets (Spinetta a Tavola), or those graceful pentangular instruments, without covers attached, which are so much prized for their external beauty. The oldest bearing a date is in the Conservatoire at Paris, by Francesco di Portalupis, Verona, 1523. [App. p.795 "In the Bologna Exhibition, 1888, Historical Section, was shown a spinet bearing the inscription 'Alessandro Pasi Modenese,' and a date, 1490. It was exhibited by Count L. Manzoni. It is a true Italian spinet in a bad state of repair. The date, which has been verified, does not invalidate the evidence adduced from Scaliger and Banchieri concerning the introduction of the spinet, but it places it farther back and before Scaliger, who was born in 1484, could have observed it. This Bologna Loan Collection contained, as well as the earliest dated spinet, the latest dated harpsichord (1802, Clementi) known to the writer."] The next by Antoni Patavini, 1550, is at Brussels. [App. p.796 "Miss Marie Decca owns a Rosso spinet dated 1550, and there is another by the same maker (signed Annibalis Mediolanesis) dated 1569, recently in the possession of Heir H. Kohl, Hamburg, who obtained it from the palace of the San Severino family, at Crema, in Lombardy. These spinets are usually made entirely of one wood, the soundboard as well as the case. The wood appears to be a kind of cedar, from its odour when planed or cut, at least in some instances that have come under the writer's notice."] We have at S. Kensington two by Annibal Rosso of Milan, 1555 and 1577, and one by Marcus Jadra (Marco dai Cembali; or dalle Spinette) 1568. Signor Kraus has, at Florence, two 16th-century spinets, one of which is signed and dated, Benedictus Florianus, 1571; and at the Hôtel Cluny, Paris, there is one by the Venetian Baffo, date 1570, whose harpsichord (clavicembalo) at S. Kensington is dated 1574.[2]

For the pentangular or heptangular model it is probable that we are indebted to Annibal Rosso, whose instrument of 1555 is engraved in the preceding illustration. Mr. Carl Engel has reprinted in the S. Kensington Catalogue (1874, p. 273) a passage from 'La Nobilita di

Milano' (1595), which he thus renders:—'Hannibal Rosso was worthy of praise, since he was the first to modernise clavichords into the shape in which we now see them,' etc. The context clearly shows that by 'clavichord' spinet was meant, clavicordo being used in a general sense equivalent to the German Clavier. If the modernising was not the adoption of the beautiful forms shown in the splendid examples at South Kensington—that by Rosso, of 1577, having been bought at the Paris Exhibition of 1867 for £1200 on account of the 1928 precious stones set into the case—it may possibly have been the wingform, with the wrestpins above the keys in front, which must have come into fashion about that time, and was known in Italy as the Spinetta Traversa; in England as the Stuart, Jacobean, or Queen Anne spinet, or Couched Harp. There is a very fine Spinetta Traversa, emblazoned with the arms of the Medici and Compagni families, in the Kraus Museum (1878, no. 193). Prætorius illustrates the Italian spinet by this special form, speaks ( Organographia,' Wolfenbüttel, 1619) of larger and smaller spinets, and states that in the Netherlands and England the larger was known as the Virginal. The smaller ones he describes as 'the small triangular spinets which were placed for performance upon the larger instruments, and were tuned an octave higher.' Of this small instrument there are specimens in nearly all museums; the Italian name for it being 'Ottavina' (also 'Spinetta di Serenata'). We find them fixed in the bent sides of the long harpsichords, in two remarkable specimens; one of which, by Hans Ruckers,[3] is preserved in the Kunst-und-Gewerbe Museum, Berlin (there is a painting of a similar double instrument inside the lid): the other is in the Maison Plantin, Antwerp, and was made as late as 1734–5, by Joannes Josephus Coenen at Ruremonde in Holland. In rectangular instruments the octave one was removeable, as it was in those double instruments mentioned under Ruckers (p. 195b), so that it could be played in another part of the room.

According to Mersenne, who treats of the spinet as the principal keyed instrument ('Harmonie,' 1636, liv. 3, p. 101, etc.), there were three sizes; one of 2½ feet, tuned to the octave of the 'ton de chapelle' (which was about a tone higher than our present high concert pitch); one of 3½ feet tuned to a fourth above the same pitch; and the large 5-feet ones, tuned in unison to it. We shall refer to his octave spinet in another paragraph.

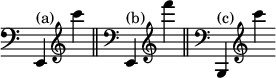

The compass of the Ottavine was usually from E to C, three octaves and a sixth (a); of the larger 16th-century Italian spinette, four octaves and a semitone, from E to F (b). The French epinettes of the 17th century were usually deeper, having four octaves and a semitone from B to C (c).

The reason for this semitonal beginning of the keyboard is obscure unless the lowest keys were used for 'short octave' measure, an idea which suggested itself simultaneously to the writer and to Professor A. Kraus, whose conviction is very strong as to the extended practice of the short octave arrangement. The Flemish picture of St. Cecilia, in Holyrood Palace, shows unmistakeably a short octave organ keyboard as early as 1484.[4]

Mersenne's express mention of C as the longest string shows that the still deeper G and A were made so, in his spinet, by weight: an important fact, as we have not seen a spinet in which it could have been otherwise, since in large instruments the bridge is always unbroken in its graceful curve, as it is also in the angles—always preserved—of the bridge of an octave one. The intimate connection of the spinet and organ keyboards must palliate a trespass upon ground that has been authoritatively covered in Organ (p. 588). It is this connection that incites inquiry into the origin of the short octaves, of which there are two measures, the French, German or English C one, which we have described, and the Italian F one, which we will now consider. We propose to call this F, from the pitch note, as before. We have reason to believe these pitch notes originally sounded the same, from which arose the original divergence of high and low church-pitch; the C instrument being thus thrown a fourth higher. The Italian short measure having been misapprehended we have submitted the question of its construction to the high authority of Professor Rraus, and of Mr. W. T. Best, who has recently returned from an examination of the organs in Italy. Both are in perfect agreement. Professor Kraus describes the Italian short octave as a progression of three dominants and tonics, with the addition of B molle (♭) and B quadro (♮) for the ecclesiastical tones. The principle, he writes, was also applied to the pedal keyboards, which are called 'Pedaliera in Sesta,' or 'Pedaliera a ottava ripiegata.'[6] Professor Kraus maintains the nearly general use of the short octave in Italian spinets, harpsichords, clavichords, and organs, and to some harpsichords he adds even another dominant.

According to this, the oldest harpsichord known to exist, the Roman one of 1521, at S. Kensington, is a short octave F instrument. [App. p.796 "The spinet by Antonio of Padua of 1550 has distinctly written on the lowest E key, the next being F, etc., but although the writing is very old, it does not follow that it was written when the instrument was made."] But extended keyboards existed contemporaneously, since the Pisan harpsichord of 1526 is continued down to F, omitting the lowest F♯ and G♯. B♭ and B♮ are, of course, there. When, in the last century, the C short octaves were made long, it was by carrying down the G and A, and giving back the semitonal value to the B and C♯ (sometimes also the D♯); but G♯ was not introduced, since it was never required as a dominant. The dominants had sometimes given way to semitones as early as the 14th and 15th centuries.

What was then the original intention of 'short measure'? We find it indicated in Mersenne's Psaltery (G C D E F G A B♭ C d e f g) and in many delineations of Portatives or Regals in pictures of the old masters, whose sincerity, seeing the accurate manner in which they have painted lutes, cannot be questioned. We will confine our references to Orcagna's 'Coronation of the Virgin' (1350), in the National Gallery, London, and Master Stephen's 'Virgin of the Rosary' (1450), at Cologne, with the Holyrood picture of 1484, already referred to as an illustration of a Positive organ with short measure. May not Dr. Hopkins's quotation [Organ, vol. ii. p. 585] of two long pipes in an organ of 1418 count as evidence for short measure as much as for pedals? We think so. In fine we regard short measure as having been intended to supply, in deeper toned instruments, dominants for cadences, and in the shriller regals (which were no more than boxes of pitch-pipes, one, two, or three to a key), to prompt the intonation of the plainsong. The contraction of the keyboard, whether diatonic or chromatic, to suit the size of the hand, was probably due to these small instruments—

Orgues avait bien maniables,

A une seulle main portables,

Ou il me mes souffle et touche.

Roman de la Rose.

The contraction to the short octave measure might have been intended to get rid of the weight of the heavier pipes not needed for dominants or intonation, and, at the same time, keep the keyboard narrow. Both contractions—the keyboard and the short measure—were thus ready made for the spinet, harpsichord and clavichord, when they came into use.

The short octave group was finally partially doubled, so as to combine with the dominant fourths the ordinary chromatic scheme, by dividing the lowest sharps or chromatics, of which there is an example in a spinet by Pleyer or Player, made between 1710 and 1720, exhibited by Messrs. Kirkman at S. Kensington in 1872. This instrument, with black naturals, and apparently 4½ octaves from B to D, has the lowest C♯ and D♯ divided, called in the quotation in the Catalogue (p. 12) 'quarter tones.' But it is difficult to imagine enharmonic intervals provided for the deepest notes. We believe it to have been intended for a 'short octave,' and to be thus explained:–

| D♭C♯ | E♭D♯ | ||||||

| Apparent notes | B | C | D | E | |||

| C♯A | E♭B | ||||||

| Real notes | G | C | D | E, | |||

| C♯D♭ | D♯E♭ | ||||||

| or | Apparent notes | B | C | D | E | ||

| AC♯ | BE♭ | ||||||

| Real notes | G | C | D | E |

A spinet by Keene, dated 1685, in possession of Mr. H. J. Dale, Cheltenham, and one by the same maker belonging to Mr. E. R. Hughes, of Chelsea, have the same apparently enharmonic arrangement. [App. p.796 "Handel's clavichord from Maidstone, with cut sharps, showed by the tuning when examined in 1885, that the first diagram is to be accepted as right, namely, that the nearer divisions of the cut keys are the dominants, and the back divisions, the chromatics."] One by Player (sic), lately sent to South Kensington (1882), is to be included with Messrs. Kirkman's and the Keenes, and also a Player which belongs to Mr. Amps [App. p.796 "for Mr. Amps read Dr. A. H. Mann"] of Cambridge; but a Keene of Mr. Grove's, undated, has not the cut sharps, which we are disposed to regard as for mixed dominants and chromatics, because the independent keynote value of the chromatics was, about a.d. 1700, beginning to be recognised, and the fretted clavichords were soon to give way to those without frets. It was the dawn of Bach, who set all notes free as tonics. We see in Keene and Player's spinets the blending of old and new, that which was passing away and our modern practice.

Returning to the Spinetta Traversa, we find this model preferred in England in the Stuart epoch, and indeed in fashion for 150 years. The favourite makers during the reigns of Charles I. and II. were John and Thomas Hitchcock and Charles Haward,[7] but there is an unaccountable difference between John Hitchcock's and Charles Haward's spinets in the fine specimens known to the writer, both the property of Mr. William Dale of London, the latter of much older character, though probably made subsequent to the former.

Thomas Hitchcock's spinets are better known than John's. The one in the woodcut belongs to Messrs. Broadwood, and is numbered 1379.[8] (The highest number we have met with of Thomas Hitchcock, is 1547.)

April 4, 1668. To White Hall. Took Aldgate Street in my way and there called upon one Hayward that makes Virginalls, and there did like of a little espinette, and will have him finish it for me: for I had a mind to a small harpsichon, but this takes up less room.

July 10. 1668. To Haward's to look upon an Espinette, and I did come near to buying one, but broke off. I have a mind to have one.

July 13, 1668. I to buy my espinette, which I did now agree for, and did at Haward's meet with Mr. Thacker, and heard him play on the harpsichon, so as I never heard man before, I think.

July 15, 1668. At noon is brought home the espinette I bought the other day of Haward; costs me 5l.

Another reference concerns the purchase of Triangles for the spinet—a three-legged stand, as in our illustration. A curious reference to Charles Haward occurs in 'A Vindication of an Essay to the advancement of Musick,' by Thomas Salmon,[9] M.A., London, 1672. This writer is advocating a new mode of notation, in which the ordinary clefs were replaced by B. (bass), M. (mean), and T. (treble) at the signatures:

Here, Sir, I must acquaint you in favour of the aforesaid B. M. T. that t'other day I met with a curious pair of Phanatical Harpsecliords made by that Arch Heretick Charles Haward, which were ready cut out into octaves (as I am told he abusively contrives all his) in so much that by the least hint of B. M. T. all the notes were easily found as lying in the same posture in every one of their octaves. And that, Sir, with this advantage, that so soon as the scholar had learned one hand he understood them, because the position of the notes were for both the same.

The lettering over the keys in Mr. W. Dale's Haward spinet is here shown to be original. It is very curious however to observe Haward's simple alphabetical lettering, and to contrast it with the Hexachord names then passing away. There is a virginal (oblong spinet) in York Museum, made in 1651 by Thomas White, on the keys of which are monograms of Gamaut (bass G) and the three clef keys F fa ut, C sol fa ut, and G sol re ut!

Mace, in 'Musick's Monument' (London, 1676), refers to John Hayward as a 'harpsichon' maker, and credits him with the invention of the Pedal for changing the stops. There was a spinet by one of the Haywards or Hawards left by Queen Anne to the Chapel Royal boys. It was used as a practising instrument until the chorister days of the late Sir John Goss, perhaps even later.

Stephen Keene was a well-known spinet-maker in London in the reign of Queen Anne. His spinets, showing mixed Hitchcock and Haward features, accepting Mr. Hughes's instrument as a criterion, reached the highest perfection of spinet tone possible within such limited dimensions. The Baudin spinet, dated 1723, which belonged to the late Dr. Rimbault, and is engraved in his History of the Pianoforte, p. 69, is now in the possession of Mr. Taphouse of Oxford. Of later 18th-century spinets we can refer to a fine one by Mahoon, dated 1747, belonging to Mr. W. H. Cummings, and there is another by that maker, who was a copyist of the Hitchcocks, at S. Kensington Museum. Sir F. G. Ouseley owns one by Haxby of York, 1766; and there is one by Baker Harris of London, 1776, in the Music School at Edinburgh. Baker Harris's were often sold by Longman & Broderip, the predecessors in Cheapside of Clementi & Collard. It is not surprising that an attempt should have been made, while the pianoforte was yet a novelty, to construct one in this pleasing wing-shape. Crang Hancock, of Tavistock Street, Covent Garden, made one in 1782 which was long in the possession of Mr. Walter Broadwood. It is now at Godalming.[ A. J. H. ]

- ↑ With reference to the early use of leather for plectra, as mentioned in Harpsichord, we now consider the evidence of existing instruments as very doubtful, owing to their having possibly been altered during repairs. The old Italian jacks were provided with little steel springs to bring back the plectra to an upright position. The bristles were later in date. See the Pisan clavicembalo and Mr. Fairfax Murray's spinet now at Florence. [App. p.795 "and the upright spinet from the Correr collection, belonging to Mr. George Donaldson, which had also plectra of brass. It is therefore possible that the use of the quill superseded that of brass."]

- ↑ Since the article Harpsichord was written, an Italian clavicembalo has been acquired for South Kensington, that is now the oldest keyed instrument in existence, with a date. It is a single keyboard harpsichord with two strings to each key; the compass nearly 4 octaves, from E to D. The natural keys are of boxwood. The inscription is 'Aspicite ut trahitur suavi Modulamine Vocis. Quicquid habent aer sidera terra fretrum. Hieronymus Bononiensis Faciebat Eomae mdxxi.' The outer case of this instrument is of stamped leather. It was bought of a 'brocanteur' in Paris for 120l. We know of no other instrument by Geronimo of Bologna. Another harpsichord nearly as old has been seen by the writer this year (1882) in Messrs. Chappell's warehouse. It is a long instrument in an outer painted case. The belly and marking off are evidently not original, but the keyboard of boxwood with black sharps has not been meddled with. There are 3½ octaves from F to C; the lowest F♯ and G♯ are omitted. The maker's inscription, nearly illegible, records that the instrument was made by a Florentine at Pisa, in 1526.

- ↑ This rare Hans Ruckers harpsichord was seen by the writer subsequent to the compilation of the catalogue appended to the article Ruckers. As others have also been found, the following particulars of them complete the above-mentioned list to 1882. [See also Virginalls.]

Hans Ruckers the Elder

Form. Date. Dimensions. General Description. Present Owner. Source of information. ft. in. ft. in. Bent side harpsichord with octave spinet in one. 1594 5 11 by 2 6 2 keyboards; the front one 4 oct., C—C; the side one 3½ Oct., E—A, without the highest G♯; 3 stops in original position at the right-hand side; white naturals. Rose No. 1; and Rose to octave spinet an arabesque. Painting inside top showing a similar combined instrument. Inscribed Hans Ruckers me fecit Antwerpia. Gewerbe Museum, Berlin. A. J. Hipkins. Hans Ruckers the Younger. Bent side. 1629 7 4 by 8 0 2 keyboards; 58 keys. G—F; black naturals. Rose No. 4. M. Gerard de Prins, Louvain. F. P. de Prins, Limerick. Andries Ruckers the Elder.

Bent side. … 6 1 by 2 10½ 1 keyboard; 4 oct., C—C; without lowest C#; white naturals. Rose No. 6; painting of a hunt. M. G. de Prins. F. P. de Prins. Bent side. 1646 7 5 by 3 0 2 keyboards, each 5 oct.; black naturals. Rose No. 6. Inscribed Andrea Ruckers me fecit Antverpiae. M. Paul Endel, Paris. P. Endel. - ↑ Hubert, or Jan. Van Eyck's St. Cecilia, in the famous Mystic Lamb, may be referred to here although appertaining to the organ and not the spinet, as a valuable note by the way. The original painting, now at Berlin, was probably painted before 1426 and certainly before 1432. The painter's minute accuracy is unquestionable. It contains a chromatic keyboard like the oldest Italian, with boxwood naturals and black sharps. The compass begins in the bass at the half-tone E. There is no indication of a 'short octave,' but there is one key by itself, convenient to the player's left hand; above this key there is a latchet acting as a catch, which may be intended to hold it down as a pedal. D is the probable note, and we have in Van Eyck's organ, it seems to us, the same compass, but an octave lower, as in the German Positif of the next century at South Kensington viz.—D. E, then 8 chromatic octaves from F, and finally F♯, G, A. There is no bottomrail to the keyboard, nor is there in the painting at Holyrood.

- ↑ It may have been on account of the tuning that A and D were left unfretted in the old 'gebunden' or fretted clavichords; but the double Irish harp which Galilei (Dissertation on Ancient and Modern Music, A.D. 1581) says had been adopted in Italy, had those notes always doubled in the two rows of strings, an importance our tuning hypothesis fails to explain.

- ↑ But not 'Ottava Rubata,' which some inaccurately apply to the lowest octave of the short octave manual. This is a contrivance in small organs with pedals to disguise the want of the lowest diapason octave on the manual, by coupling on to it the contrabasso of the pedals with the register of the octave above.

- ↑ The statement in Harpsichord that there was no independent harpsichord-making apart from organ-building in England during the 17th century is now contradicted by the fact of these spinet-makers having also made harpsichords, 'harpsicons' as the English then preferred to call them. There is a harpsichord of 5 octaves F-F by John Hitchcock in the possession of Mr. W. J. Legh of Lyme, Cheshire. It is without date, but is numbered inside 3. Mr. Dale's John Hitchcock spinet is numbered inside 21 and dated 1630. [App. p.796 "1630, on Mr. W. Dale's spinet, is not a date; it is the maker's number."] A name, Sam or Sams, apparently a workman's, is found in both instruments.

- ↑ This is the instrument in Mr. Millais' picture of 'The Minuet,' 1862. Thomas dated his spinets; John numbered them.

- ↑ Salmon, Thomas, born at Hackney, Middlesex, in 1648, was on April 8, 1684, admitted a commoner of Trinity College, Oxford. He took the degree of M.A. and became rector of Mepsal [Meppershall?], Bedfordshire. In 1672 be published 'An Essay to the Advancement of Musick, by casting away the perplexity of different Cliffs, and uniting all sorts of Musick in one universal character.' His plan was that the notes should always occupy the same position on the stave. without regard as to which octave might be used; and he chose such position from that on the bass stave—i.e. G was to be always on the lowest line. Removing the bass clef, he substituted for it the capital letter B. signifying Bass. In like manner be placed at the beginning of the next stave the letter M (for Mean), to indicate that the notes were to be sung or played an octave higher than the bass; and to the second stave above prefixed the letter T (for Treble), to denote that the notes were to be sounded two octaves above the bass. Matthew Lock criticised the scheme with great asperity, and the author published a 'Vindication' of it, to which Lock and others replied. [See Lock, Matthew.] In 1688 Salmon published 'A Proposal to perform Music in Perfect and Mathematical Proportions,' which, like his previous work, met with no acceptance.

[ W. H. H. ]