A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Tempo

TEMPO (Ital., also Movimento; Fr. Mouvement). This word is used in both English and German to express the rate of speed at which a musical composition is executed. The relative length of the notes depends upon their species, as shown in the notation, and the arrangement of longer and shorter notes in bars must be in accordance with the laws of Time, but the actual length of any given species of note depends upon whether the Tempo of the whole movement be rapid or the reverse. The question of Tempo is a very important one, since no composition could suffer more than a very slight alteration of speed without injury, while any considerable change would entirely destroy its character and render it unrecognisable. The power of rightly judging the tempo required by a piece of music, and of preserving an accurate recollection of it under the excitement caused by a public performance, is therefore not the least among the qualifications of a conductor or soloist.

Until about the middle of the 17th century, composers left the tempi of their compositions (as indeed they did the nuances to a great extent) entirely to the judgment of performers, a correct rendering being no doubt in most cases assured by the fact that the performers were the composer's own pupils; so soon however as the number of executants increased, and tradition became weakened, some definite indication of the speed desired by the composer was felt to be necessary, and accordingly we find all music from the time of Bach[1] and Handel (who used tempo-indications but sparingly) marked with explicit directions as to speed, either in words, or by a reference to the Metronome, the latter being of course by far the most accurate method. [See vol. ii. p. 318.]

Verbal directions as to tempo are generally written in Italian, the great advantage of this practice being that performers of other nationalities, understanding that this is the custom, and having learnt the meaning of the terms in general use, are able to understand the directions given, without any further knowledge of the language. Nevertheless, some composers, other than Italians, have preferred to use their own native language for the purpose, at least in part. Thus Schumann employed German terms in by far the greater number of his compositions, not alone as tempo-indications but also for directions as to expression,[2] and Beethoven took a fancy at one time for using German,[3] though he afterwards returned to Italian. [See vol. i. p. 193.]

The expressions used to denote degrees of speed may be divided into two classes, those which refer directly to the rate of movement, as Lento—slow; Adagio—gently, slowly; Moderato—moderately; Presto—quick, etc.; and those (the more numerous) which rather indicate a certain character or quality by which the rate of speed is influenced, such as Allegro—gay, cheerful; Vivace—lively; Animato—animated; Maestoso—majestically; Grave—with gravity; Largo—broad; etc. To these last may be added expressions which allude to some well-known form of composition, the general character of which governs the speed, such as Tempo di Minuetto—in the time of a Minuet; Alla Marcia, Alla Polacca—in the style of a march, polonaise, and so on. Most of these words may be qualified by the addition of the terminations etto and ino, which diminish, or issimo, which increases, the effect of a word. Thus Allegretto, derived from Allegro, signifies moderately lively, Prestissimo—extremely quick, and so on. The same varieties may also be produced by the use of the words molto—much; assai—very; più—more; meno—less; un poco (sometimes un pochettino[4])—a little; non troppo—not too much, etc.

The employment, as indications of speed, of words which in their strict sense refer merely to style and character (and therefore only indirectly to tempo), has caused a certain conventional meaning to attach to them, especially when used by other than Italian composers. Thus in most vocabularies of musical terms we find Allegro rendered as 'quick,' Largo as 'slow,' etc., although these are not the literal translations of the words. In the case of at least one word this general acceptance of a conventional meaning has brought about a misunderstanding which is of considerable importance. The word is Andante, the literal meaning of which is 'going,'[5] but as compositions to which it is applied are usually of a quiet and tranquil character, it has gradually come to be understood as synonymous with 'rather slow.' In consequence of this, the direction più andante, which really means 'going more' i.e. faster, has frequently been erroneously understood to mean slower, while the diminution of andante, andantino, literally 'going a little,' together with meno andante—'going less'—both of which should indicate a slower tempo than andante—have been held to denote the reverse. This view, though certainly incorrect, is found to be maintained by various authorities, including even Koch's 'Musikalisches Lexicon,' where più andante is distinctly stated to be slower, and andantino quicker, than andante. In a recent edition of Schumann's 'Kreisleriana' we find the composer's own indication for the middle movement of No. 3, 'Etwas langsamer,' incorrectly translated by the editor poco più andante, which coming immediately after animato has a very odd effect. Schubert also appears to prefer the conventional use of the word, since he marks the first movement of his Fantasia for Piano and Violin, op. 159, Andante molto. But it seems clear that, with the exception just noted, the great composers generally intended the words to bear their literal interpretation. Beethoven, for instance, places his intentions on the subject beyond a doubt, for the 4th variation in the Finale of the Sonata op. 109 is inscribed in Italian 'Un poco meno andante, cio è, un poco più adagio come il tema'[6]—a little less andante, that is, a little more slowly like (than?) the theme,' and also in German Etwas langsamer als das Thema—somewhat slower than the theme. Instances of the use of più andante occur in Var. 5 of Beethoven's Trio op. 1, no. 3, in Brahms's Violin Sonata op. 78, where it follows (of course with the object of quickening) the tempo of Adagio, etc. Handel, in the air 'Revenge, Timotheus cries!' and in the choruses 'For unto us' and 'The Lord gave the word,' gives the direction Andante allegro, which may be translated 'going along merrily.'

When in the course of a composition the tempo alters, but still bears a definite relation to the original speed, the proportion in which the new tempo stands to the other may be expressed in various ways. When the speed of notes of the same species is to be exactly doubled, the words doppio movimento are used to denote the change, thus the quick portion of Ex. 1 would be played precisely as though it were written as in Ex. 2.

Brahms, Trio, op. 8.

![{ \relative g { \clef bass \key b \major \time 4/4 \mark \markup \small "2." \tempo "Adagio" \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f

r8 gis( cis ais) fis( b16 dis fis8[ gis] | cis,8) } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/9/k/9k52t13l8mzo3ihxfsmmmesidvjtgcn/9k52t13l.png)

Another way of expressing proportional tempi is by the arithmetical sign for equality (=), placed between two notes of different values. Thus ![]() =

= ![]() would mean that a crochet in the one movement must have the same duration as a minim in the other, and so on. But this method is subject to the serious drawback that it is possible to understand the sign in two opposed senses, according as the first of the two note-values is taken to refer to the new tempo or to that just quitted. On this point composers are by no means agreed, nor are they even always consistent, for Brahms, in his 'Variations on a Theme by Paganini,' uses the same sign in opposite senses, first in passing from Var. 3 to Var. 4, where a

would mean that a crochet in the one movement must have the same duration as a minim in the other, and so on. But this method is subject to the serious drawback that it is possible to understand the sign in two opposed senses, according as the first of the two note-values is taken to refer to the new tempo or to that just quitted. On this point composers are by no means agreed, nor are they even always consistent, for Brahms, in his 'Variations on a Theme by Paganini,' uses the same sign in opposite senses, first in passing from Var. 3 to Var. 4, where a ![]() of Var. 4 equals a

of Var. 4 equals a ![]() quarter note of Var. 3 (Ex. 3), and afterwards from Var. 9 to Var. 10, a

quarter note of Var. 3 (Ex. 3), and afterwards from Var. 9 to Var. 10, a ![]() of Var. 10 being equal to a

of Var. 10 being equal to a ![]() of Var. 9 (Ex. 4).

of Var. 9 (Ex. 4).

![{ \new Staff << \mark \markup \small "Ex. 3. Var. 3." \time 6/8 \partial 8

\new Voice \relative e'' { \stemUp

s8 | e16 s8. g,16[ bes] e s8. f,16[ a] | }

\new Voice \relative a' { \stemDown

a16[ c] | s e[ b gis] s8. e'16[ a, fis] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/j/y/jyhp8tdi09uqyy0i7pmupk36tdv1ssc/jyhp8tdi.png)

![{ \new Staff << \mark \markup \small "Var. 4" \tempo \markup { \concat { ( \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {4} #1 " = " \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {8} #1 ) } } \time 12/16

\new Voice \relative e''' { \stemUp

<e c^( e,>8.[\startTrillSpan <e) c>8 dis16]\stopTrillSpan

<e g,^( e>8.[\startTrillSpan <e) b>8 dis16]\stopTrillSpan }

\new Voice \relative a { \stemDown

a16[ a' c c' c, a] g,[ g' b b' b, g] } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/r/dr36yytn147xq1229gkjzhpcapjcm9w/dr36yytn.png)

![{ \relative e' { \mark \markup \small "Var. 10." \tempo \markup { \concat { ( \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {4} #1 " = " \smaller \general-align #Y #DOWN \note {8} #1 ) } } \time 2/4

r16 <e c>8[ <d b> <c a> <d b>16] ~ |

q16 <e c>8.\noBeam r16 <fis dis cis>8. } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/o/m/om9nnqhihh9nfookh07yk89f4nxp79h/om9nnqhi.png)

A far safer means of expressing proportion is by a definite verbal direction, a method frequently adopted by Schumann, as for instance in the 'Faust' music, where he says Ein Takt wie vorher zwei—one bar equal to two of the preceding movement; and Um die Hälfte langsamer (by which is to be understood twice as slow, not half as slow again), and so in numerous other instances.

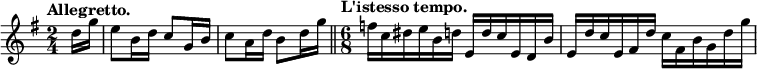

When there is a change of rhythm, as from common to triple time, while the total length of a bar remains unaltered, the words l'istesso tempo, signifying 'the same speed,' are written where the change takes place, as in the following example, where the crotchet of the 2-4 movement is equal to the dotted crotchet of that in 6-8, and so, bar for bar, the tempo is unchanged.

Beethoven, Bagatelle, op. 119, No. 6.

The same words are occasionally used when there is no alteration of rhythm, as a warning against a possible change of speed, as in Var. 3 of Beethoven's Variations, op. 120, and also, though less correctly, when the notes of any given species remain of the same length, while the total value of the bar is changed, as in the following example, where the value of each quaver remains the same, although the bar of the 2-4 movement is only equal to two-thirds of one of the foregoing bars.

Beethoven, Bagatelle, op. 126, No. 1.

![{ \relative b' { \key g \major \time 3/4 \tempo "Andante con moto." \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

<< { b8 a a4 a^( | a4. fis8 b a) } \\

{ g4 f e | f( d) r } >> \bar "||"

\time 2/4 \tempo "L'istesso tempo."

r8 e([ b' a)] | r g([ b a)] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/7/e/7e0vvg15zlrv3ojmry2l0v01p4ltoit/7e0vvg15.png)

A gradual increase of speed is indicated by the word accelerando or stringendo, a gradual slackening by rallentando or ritardando. All such effects being proportional, every bar and indeed every note should as a rule take its share of the general increase or diminution, except in cases where an accelerando extends over many bars, or even through a whole composition. In such cases the increase of speed is obtained by means of frequent slight but definite changes of tempo (the exact points at which they take place being left to the judgment of performer or conductor) much as though the words più mosso were repeated at intervals throughout. Instances of an extended accelerando occur in Mendelssohn's chorus, 'O! great is the depth,' from 'St. Paul' (26 bars), and in his Fugue in E minor, op. 35, no. 1 (63 bars). On returning to the original tempo after either a gradual or a precise change the words tempo primo are usually employed, or sometimes Tempo del Tema, as in Var. 12 of Mendelssohn's 'Variations Sérieuses.'

The actual speed of a movement in which the composer has given merely one of the usual tempo indications, without any reference to the metronome, depends of course upon the judgment of the executant, assisted in many cases by tradition. But there are one or two considerations which are of material influence in coming to a conclusion on the subject. In the first place, it would appear that the meaning of the various terms has somewhat changed in the course of time, and in opposite directions, the words which express a quick movement now signifying a yet more rapid rate, at least in instrumental music, and those denoting slow tempo a still slower movement, than formerly. There is no absolute proof that this is the case, but a comparison of movements similarly marked, but of different periods, seems to remove all doubt. For instance, the Presto of Beethoven's Sonata, op. 10, no. 3, might be expressed by M.M. ![]() = 144, while the Finale of Bach's Italian Concerto, also marked Presto, could scarcely be played quicker than

= 144, while the Finale of Bach's Italian Concerto, also marked Presto, could scarcely be played quicker than ![]() = 126 without disadvantage. Again, the commencement of Handel's Overture to the 'Messiah' is marked Grave, and is played about

= 126 without disadvantage. Again, the commencement of Handel's Overture to the 'Messiah' is marked Grave, and is played about ![]() = 60, while the Grave of Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique requires a tempo of only

= 60, while the Grave of Beethoven's Sonata Pathétique requires a tempo of only ![]() = 60, exactly twice as slow. The causes of these differences are probably on the one hand the greatly increased powers of execution possessed by modern instrumentalists, which have induced composers to write quicker music, and on the other, at least in the case of the pianoforte, the superior sostenuto possible on modern instruments as compared with those of former times. The period to which the music belongs must therefore be taken into account in determining the exact tempo. But besides this, the general character of a composition, especially as regards harmonic progression, exercises a very decided influence on the tempo. For the apparent speed of a movement does not depend so much upon the actual duration of the beats, as upon the rate at which the changes of harmony succeed each other. If, therefore, the harmonies in a composition change frequently, the tempo will appear quicker than it would if unvaried harmonies were continued for whole bars, even though the metronome-time, beat for beat, might be the same. On this account it is necessary, in order to give effect to a composer's indication of tempo, to study the general structure of the movement, and if the changes of harmony are not frequent, to choose a quicker rate of speed than would be necessary if the harmonies were more varied. For example, the first movement of Beethoven's Sonata, op. 22, marked Allegro, may be played at the rate of about

= 60, exactly twice as slow. The causes of these differences are probably on the one hand the greatly increased powers of execution possessed by modern instrumentalists, which have induced composers to write quicker music, and on the other, at least in the case of the pianoforte, the superior sostenuto possible on modern instruments as compared with those of former times. The period to which the music belongs must therefore be taken into account in determining the exact tempo. But besides this, the general character of a composition, especially as regards harmonic progression, exercises a very decided influence on the tempo. For the apparent speed of a movement does not depend so much upon the actual duration of the beats, as upon the rate at which the changes of harmony succeed each other. If, therefore, the harmonies in a composition change frequently, the tempo will appear quicker than it would if unvaried harmonies were continued for whole bars, even though the metronome-time, beat for beat, might be the same. On this account it is necessary, in order to give effect to a composer's indication of tempo, to study the general structure of the movement, and if the changes of harmony are not frequent, to choose a quicker rate of speed than would be necessary if the harmonies were more varied. For example, the first movement of Beethoven's Sonata, op. 22, marked Allegro, may be played at the rate of about ![]() = 72, but the first movement of op. 31, no. 2, though also marked Allegro, will require a tempo of at least

= 72, but the first movement of op. 31, no. 2, though also marked Allegro, will require a tempo of at least ![]() = 120, on account of the changes of harmony being less frequent, and the same may be observed of the two adagio movements, both in 9-8 time, of op. 22 and op. 31, no. 1; in the second of these most bars are founded upon a single harmony, and a suitable speed would be about

= 120, on account of the changes of harmony being less frequent, and the same may be observed of the two adagio movements, both in 9-8 time, of op. 22 and op. 31, no. 1; in the second of these most bars are founded upon a single harmony, and a suitable speed would be about ![]() = 116, a rate which would be too quick for the Adagio of op. 22, where the harmonies are more numerous.[7]

= 116, a rate which would be too quick for the Adagio of op. 22, where the harmonies are more numerous.[7]

Another cause of greater actual speed in the rendering of the same tempo is the use of the time-signature ![]() or alla breve, which requires the composition to be executed at about double the speed of the Common or

or alla breve, which requires the composition to be executed at about double the speed of the Common or ![]() Time. The reason of this is explained in the article Breve, vol. i. p. 274.

Time. The reason of this is explained in the article Breve, vol. i. p. 274.

[ F. T. ]

- ↑ In the 48 Preludes and Fugues there is but one tempo-indication. Fugue 24, vol. i. is marked 'Largo,' and even this is rather an indication of style than of actual speed.

- ↑ He used Italian terms in op. 1–4, 7–11, 13–15, 38, 41, 44, 47, 52, 54, and 61; the rest are in German.

- ↑ Beethoven's German directions occur chiefly from op. 81a to 101, with a few isolated instances as far on as op. 128.

- ↑ See Brahms, op. 34. Finale.

- ↑ The word is derived from andare, 'to go.' In his Sonata op. 81a, Beethoven expresses Andante by the words In gehender Bewegung—in going movement.

- ↑ Beethoven's Italian, however, does not appear to have been faultless, for the German translation above shows him to have used the word come to express 'than' instead of 'like.'

- ↑ Hummel, in his 'Pianoforte School,' speaking in praise of the Metronome, gives a list of instances of the variety of meanings attached to the same words by different composers, in which we find Presto varying from

= 72 to

= 72 to  = 224. Allegro from

= 224. Allegro from  = 50 to

= 50 to  = 172, Andante from

= 172, Andante from  = 52 to

= 52 to  = 152 etc. But Hummel does not specify the particular movements he quotes, and it seems probable that, regard being had to their varieties of harmonic structure, the discrepancies may not really have been so great as at first sight appears.

= 152 etc. But Hummel does not specify the particular movements he quotes, and it seems probable that, regard being had to their varieties of harmonic structure, the discrepancies may not really have been so great as at first sight appears.