A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Thoroughbass

THOROUGHBASS (Thoroughbase, Figured-Bass; Lat. Bassus generalis, Bassus continuus; Ital. Continuo, Basso continuo[1]; Germ. General-bass; Fr. Basse continue, Basse chiffrée). An instrumental Bass-Part, continued, without interruption, throughout an entire piece of Music, and accompanied by Figures, indicating the general Harmony.

In Italy, the Figured-Bass has always been known as the Basso continuo, of which term our English word, Thorough (i.e. Through) bass, is a sufficiently correct translation. But, in England, the meaning of the term has been perverted, almost to the exclusion of its original intention. Because the Figures placed under a Thorough-bass could only be understood by a performer well acquainted with the rules of Harmony, those rules were vulgarly described as the Rules of Thoroughbass; and, now that the real Thoroughbass is no longer in ordinary use, the word survives as a synonym for Harmony—and a very incorrect one.

The invention of this form of accompaniment was long ascribed to Lodovico Viadana (1566–1644), on the authority of Michael Praetorius, Johann Cruger, Walther, and other German historians of almost equal celebrity, fortified by some directions as to the manner of its performance, appended to Viadana's 'Concerti ecclesiastici.' But it is certain that the custom of indicating the Intervals of a Chord by means of Figures placed above or below the Bass-note, was introduced long before the publication of Viadana's directions, which first appeared in a reprint of the 'Concerti' issued in 1612, and are not to be found in any earlier edition; while a true Thoroughbass is given in Peri's 'Euridice,' performed and printed in 1600; an equally complete one in Emilio del Cavaliere's Oratorio, 'La rappresentazione dell' anima e del corpo,' published in the same year; and another, in Caccini's 'Nuove Musiche' (Venice, 1602). There is, indeed, every reason to believe that the invention of the Continuo was synchronous with that of the Monodic Style, of which it was a necessary contingent; and that, like Dramatic Recitative, it owed its origin to the united efforts of the enthusiastic reformers who met, during the closing years of the 16th century, at Giovanni Bardi's house in Florence. [See Viadana, Ludovico; Monodia; Recitative; also vol. ii. p. 98.] [App. p.799 "add that the first use of a thoroughbass appears to be in a work by an English composer, Richard Dering, who published a set of 'Cantiones Sacrae' at Antwerp in 1597, in which a figured bass is employed. See Dering in Appendix, vol. iv. p. 612b."]

After the general establishment of the Monodic School, the Thoroughbass became a necessary element in every Composition, written, either for Instruments alone, or for Voices with Instrumental Accompaniment. In the Music of the 18th century, it was scarcely ever wanting. In the Operas of Handel, Buononcini, Hasse, and their contemporaries, it played a most important part. No less prominent was its position in Handel's Oratorios; and even in the Minuets and Gavottes played at Ranelagh, it was equally indispensable. The 'Vauxhall Songs' of Shield, Hook, and Dibdin, were printed on two Staves, on one of which was written the Voice-Part, with the Melody of the Ritornelli, inserted in single notes, between the verses, while the other was reserved for the Thoroughbass. In the comparatively complicated Cathedral Music of Croft, Greene, and Boyce, the Organ-Part was represented by a simple Thoroughbass, printed on a single Stave, beneath the Vocal Score. Not a chord was ever printed in full, either for the Organ, or the Harpsichord; for the most ordinary Musician was expected to play, at sight, from the Figured-Bass, just as the most ordinary Singer, in the days of Palestrina, was expected to introduce the necessary accidental Sharps, and Flats, in accordance with the laws of Cantus Fictus. [See Musica Ficta.]

The Art of playing from a Thoroughbass still survives—and even flourishes—among our best Cathedral Organists. The late Mr. Turle, and Sir John Goss, played with infinitely greater effect from the old copies belonging to their Cathedral libraries, than from modern 'arrangements' which left no room for the exercise of their skill. Of course, such copies can be used only by those who are intimately acquainted with all the laws of Harmony: but, the application of those laws to the Figured Bass is exceedingly simple, as we shall now proceed to show.

1. A wholesome rule forbids the insertion of any Figure not absolutely necessary for the expression of the Composer's intention.

2. Another enacts, that, in the absence of any special reason to the contrary, the Figures shall be written in their numerical order; the highest occupying the highest place. Thus, the full figuring of the Chord of the Seventh is, in all ordinary cases, ; the performer being left at liberty to play the Chord in any position he may find most convenient. Should the Composer write , it will be understood that he has some particular reason for wishing the Third to be placed at the top of the Chord, the Fifth below it, and the Seventh next above the Bass; and the performer must be careful to observe the directions implied in this departure from the general custom.

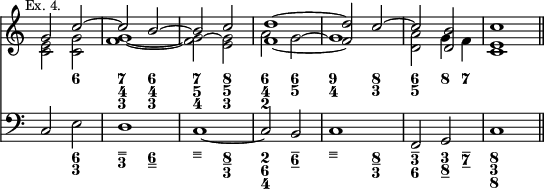

3. In conformity with Rule 1, it is understood that all Bass-notes unaccompanied by a Figure are intended to bear Common Chords. It is only necessary to figure the Common Chord, when it follows some other Harmony, on the same Bassnote. Thus, at (a), in Example 1, unless the Common Chord were figured, the would be continued throughout the Bar; and in this case, two Figures are necessary for the Common Chord, because the Sixth descends to a Fifth, and the Fourth to a Third. At (b) two Figures are equally necessary; otherwise, the performer would be perfectly justified in accompanying the lower G with the same Chord or the upper one. Instances may even occur in which three Figures are needed, as at (c), where it is necessary to show that the Ninth, in the second Chord, descends to an Eighth, in the third. But, in most ordinary cases, a 3, a 5, or an 8, will be quite sufficient to indicate the Composer's intention.

The First Inversion of the Triad is almost always sufficiently indicated by the Figure 6, the addition of the Third being taken as a matter of course; though cases will sometimes occur in which a fuller formula is necessary; as at (a), in Example 2, where the 3 is needed to show the Resolution of the Fourth, in the preceding Harmony; and at (b), where the 8 indicates the Resolution of the Ninth, and the 3, that of the Fourth. We shall see, later on, how it would have been possible to figure these passages in a more simple and convenient way.

A small treatise which was once extraordinarily popular in England, and is even now used to the exclusion of all others, in many 'Ladies Schools,' foists a most vicious rule upon the Student, with regard to this Chord; to the effect that, when the Figure 6 appears below the Supertonic of the Key, a Fourth is to be added to the Harmony. We remember, when the treatise was at the height of its popularity, hearing Sir Henry Bishop inveigh bitterly against this abuse, which he denounced as subversive of all true musical feeling; yet the pretended exception to the general law was copied into another treatise, which soon became almost equally popular. No such rule was known at the time when every one was expected to play from a Thoroughbass. Then, as now, the Figure 6 indicated, in all cases, the First Inversion of the Triad, and nothing else; and, were any such change now introduced, we should need one code of laws for the interpretation of old Thorough-Basses, and another for those of later date.

The Second Inversion of the Triad cannot be indicated by less than two Figures, . Cases may even occur, in which the addition of an 8 is needed; as, for instance, in the Organ-Point at (a), in Example 3; but these are rare.

In nearly all ordinary cases, the Figure 7 only is needed for the Chord of the Seventh; the addition of the Third and Fifth being taken for granted. Should the Seventh be accompanied by any Intervals other than the Third, Fifth, and Octave, it is, of course, necessary to specify them; and instances, analogous to those we have already exemplified when treating of the Common Chord, will sometimes demand even the insertion of a 3 or a 5, when the Chord follows some other Harmony, on the same Bass-note. Such cases are very common in Organ Points.

The Inversions of the Seventh are usually indicated by the formulæ, , and ; the Intervals needed for the completion of the Harmony being understood. Sometimes, but not very often, it will be necessary to write , or . In some rare cases, the Third Inversion is indicated by a simple 4: but this is a dangerous form of abbreviation, unless the sense of the passage be very clear indeed; since the Figure 4 is constantly used, as we shall presently see, to indicate another form of Dissonance. The Figure 2, used alone, is more common, and always perfectly intelligible; the 6 and the 4 being understood.

The Figures , whether placed under the Dominant, or under anyother Degree of the Scale, indicate a Chord of the Ninth, taken by direct percussion. Should the Ninth be accompanied by other Intervals than the Seventh, Fifth, or Third, such Intervals must be separately noticed. Should it appear in the form of a Suspension, its figuring will be subject to certain modifications, of which we shall speak more particularly when describing the figuring of Suspensions generally.

The formulæ and are used to denote the chord of the Eleventh—i.e. the chord of the Dominant Seventh, taken upon the Tonic Bass. The chord of the Thirteenth—or chord of the Dominant Ninth upon the Tonic Bass is repretented by or or . In these cases, the 4 represents the Eleventh, and the 6 the Thirteenth: for it is a rule with modern Composers to use no higher numeral than 9; though in the older Figured Basses such as those given in Peri's 'Euridice,' and Ernilio del Cavaliere's 'La Rappresentazione dell' anima e del corpo,' the numerals, 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14, are constantly used to indicate reduplications of the Third, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Seventh, in the Octave above.

Accidental Sharps, Flats, and Naturals are expressed in three different ways. A ♯, ♭, or ♮ used alone—that is to say, without the insertion of a numeral on its own level—indicates that the Third of the Chord is to be raised or depressed a Semitone, as the case may be. This arrangement is entirely independent of other numerals placed above or below the Accidental Sign, since these can only refer to other Intervals in the Chord. Thus, a Bass-note with a single ♭ beneath it, must be accompanied by a Common Chord, with a flattened Third. One marked must be accompanied by the First Inversion of the Chord of the Seventh, with its Third flattened. It is true that, in some Thoroughbasses of the last century, we find the forms ♯3, ♭3, or ♮3; but the Figure is not really necessary.

A dash drawn through a 6̸, or 4̸, indicates that the Sixth or Fourth above the Bass-note, must be raised a Semitone. In some of Handel's Thoroughbasses, the raised Fifth is indicated by 5̷; but this form is not now in use.

In all cases except those already mentioned, the necessary Accidental Sign must be placed before the numeral to which it is intended that it should apply; as ♭6, ♯7, ♮5, ♭9, ♭4, ♮4, ♮6, etc.; or, when two or more Intervals are to be altered, , , , etc.; the Figure 3 being always suppressed in modern Thoroughbasses, and the Accidental Sign alone inserted in its place when the Third of the Chord is to be altered.

By means of these formulæ, the Chord of the Augmented Sixth is easily expressed, either in its Italian, French, or German form. For instance, with the Signature of G major, and E♭ for a Bassnote, the Italian Sixth would be indicated by 6, the French by , the German by , or .

The employment of Passing-Notes, Appoggiaturas, Suspensions, Organ-Points, and other passages of like character, gives rise, sometimes, to very complicated Figuring, which, however, may be simplified by means of certain formulæ, which save much trouble, both to the Composer and the Accompanyist.

A horizontal line following a Figure, on the same level, indicates that the note to which the previous Figure refers is to be continued, in one of the upper Parts, over the new Bass-note, whatever may be the Harmony to which its retention gives rise. Two or more such lines indicate that two or more notes are to be so continued; and, in this manner, an entire Chord may frequently be expressed, without the employment of a new Figure. This expedient is especially useful in the case of Suspensions, as in Example 4, the full Figuring of which is shown above the Continue, and, beneath it, the more simple form, abbreviated by means of the horizontal lines, the arrangement of which has, in some places, involved a departure from the numerical order of the Figures.

Any series of Suspended Dissonances may be expressed on this principle—purposely exaggerated in the example—though certain very common Suspensions are denoted by special formulæ which very rarely vary. For instance, 4 3 is always understood to mean the Common Chord, with its Third delayed by a suspended Fourth—in contradistinction to already mentioned; 9 8 means the Suspended Ninth resolving into the Octave of the Common Chord; indicates the Double Suspension of the Ninth and Fourth, resolving into the Octave and Third; etc.

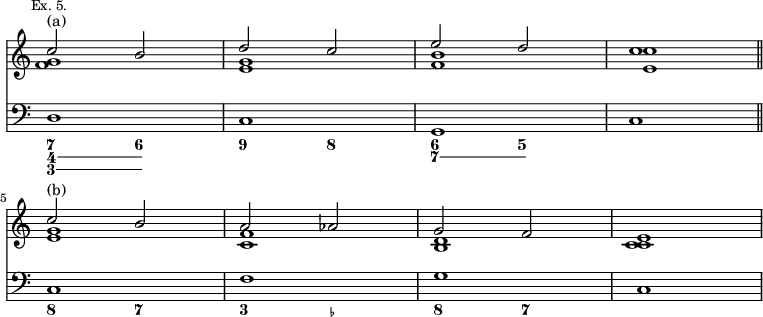

In the case of Appoggiaturas, the horizontal lines are useful only in the Parts which accompany the Discord. In the Part which actually contains the Appoggiatura, the absence of the Concord of Preparation renders them inadmissible, as at (a) in Example 5.

Passing-Notes, in the upper Parts, are not often noticed in the Figuring, since it is rarely necessary that they should be introduced into the Organ or Harpsichord Accompaniment; unless, indeed, they should be very slow, in which case they are very easily figured, in the manner shown at (b) in Example 5.

The case of Passing-Notes in the Bass is very different. They appear, of course, in the Continuo itself; and the fact that they really are Passing-Notes, and are, therefore, not intended to bear independent Harmonies, is sufficiently proved by a system of horizontal lines indicating the continuance of a Chord previously figured; as in Example 6, in the first three bars of which the Triad is figured in full, because its intervals are continued on the three succeeding Bass-Notes.

But in no case is the employment of horizontal lines more useful than in that of the Organ Point, which it would often be very difficult to express clearly without their aid. Example 7 shows the most convenient way of figuring complicated Suspensions upon a sustained Bass-Note.

![{ << \new Staff \relative c'' { \override Score.TimeSignature #'stencil = ##f \key g \major \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

<< { <cis gis>4 r8 d, d[ c] r fis |

fis[ eis] r <eis b'> b' ais r g' |

g[ fis] r e e[ d] r d | d[ c] r b ais4 b8[ cis] |

ais4. ais8 b4 r } \\

{ <cis, eis> s8 b b[ a] s a | a[ gis] r <gis c> fis2 |

b8[ cis] r g' g[ fis] s fis | e2. d4 | cis4. cis8 d4 r } \\

{ s2. s8 c | c4 r8 s <c f>4 r8 b |

s1 r2 r4 r8 g' | fis4. fis8 fis4 r } >> }

\new Staff { \clef bass cis1 ~ cis2 fis ~ fis1 g2 fis4 e fis2 b, }

\figures { \bassFigureExtendersOn

<5+ _+>4. <9 7>8 q <8 6> s <6\! 4> |

<6 4> <5+ _+>4 <7 _+>8 r <_+>4 <9 4>8 |

<9 4> <8 _+>4 <9 7>8 q <8 6>4 q8 |

<6\! 5>8 <6 4>4 <6 3>8 <7 _+>4 <7\! 5 3> | <_+>2 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/8/8/88syaabspasajngy11csrzohvb776kf/88syaabs.png)

In the Inverted Pedal-Point, the lines are still more valuable, as a means of indicating the continuance of the sustained note in an upper Part; as in Example 8, in which the Figure 8 marks the beginning of the C, which, sustained in the Tenor Part, forms the Inverted Pedal, while the horizontal line indicates its continuance to the end of the passage.

When, in the course of a complicated Movement, it becomes necessary to indicate that a certain phrase—such as the well-known Canto-Fermo in the 'Hallelujah Chorus'—is to be delivered in Unison,—or, at most, only doubled in the Octave—the passage is marked Tasto Solo, or, T. S.—i.e. 'with a single touch' (= key).[2] When the Subject of a Fugue appears, for the first time, in the Bass, this sign is indispensable. When it first appears in an upper Part, the Bass Clef gives place to the Treble, Soprano, Alto, or Tenor, as the case may be, and the passage is written in single Notes, exactly as it is to be played. In both these cases it is usual also to insert the first few Notes of the Answer, as a guide to the Accompanyist, who only begins to introduce full Chords when the figures are resumed. In any case, when the Bass Voices are silent, the lowest of the upper Parts is given in the Thoroughbass, either with or without Figures, in accordance with the law which regards the lowest sound as the real Bass of the Harmony, even though it may be sung by a Soprano Voice. An instance of this kind is shown in Example 9.

We shall now present the reader with a general example, serving as a practical application of the rules we have collected together for his guidance; selecting, for this purpose, the concluding bars of the Chorus, 'All we like sheep,' from Handel's 'Messiah.'

[ W. S. R. ]