A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Tonal Fugue

TONAL FUGUE (Fr. Fugue du Ton; Germ. Einfache Fuge, Fuge des Tones). A form of Fugue, in which the Answer (Comes), instead of following the Subject (Dux) exactly, Interval for Interval, sacrifices the closeness of its Imitation to a more important necessity—that of exact conformity with the organic constitution of the Mode in which it is written; in other words, to the Tonality of its Scale. [See Subject.]

This definition, however, though sufficient to distinguish a Tonal Fugue from a Real one of the same period and form, gives no idea whatever of the sweeping revolution which followed the substitution of the later for the earlier method. A technical history of this revolution, though giving no more than a sketch of the phases through which it passed, between the death of Palestrina and the maturity of Handel and Sebastian Bach, would fill a volume. We can here only give the ultimate results of the movement; pausing first to describe the position from which the earliest modern Fuguists took their departure.

The Real Fugue of the Polyphonic Composers, as perfected in the 16th century, was of two kinds—Limited, and Unlimited. With the Limited form now called Canon we have, here, no concern.[1] The Unlimited Real Fugue started with a very short Subject, adapted to the opening phrase of the verbal text for it was always vocal and this was repeated note for note in the Answer, but only for a very short distance. The Answer always began before the end of the Subject; but, after the exact Imitation carried on through the first few notes, the part in which it appeared became 'free,' and proceeded whither it would. The Imitation took place generally in the Fifth above or the Fourth below; sometimes in the Fourth above, or Fifth below, or in the Octave; rarely, in Unlimited Real Fugue, in any less natural Interval than these. There was no Counter-Subject; and, whenever a new verbal phrase appeared in the text, a new musical phrase was adapted to it, in the guise of a Second Subject. But it was neither necessary that the opening Subject should be heard simultaneously with the later ones; nor, that it should reappear, after a later one had been introduced. Indeed, the cases in which these two conditions—both indispensable, in a modern Fugue—were observed, even in the slightest degree, are so rare, that they may be considered as infringements of a very strict rule.

The form we have here described was brought to absolute perfection in the so-called 'School of Palestrina,' in the latter half of the 16th century. The first departure from it—rendered inevitable by the substitution of the modern Scale for the older Tonalities—consisted in the adaptation of the Answer to the newer law, in place of its subjugation, by aid of the Hexachord, to the Ecclesiastical Modes. [See Hexachord.] The change was crucial. But it was manifest that matters could not rest here. No sooner was the transformation of the Answer recognised as an unavoidable necessity, than the whole conduct of the Fugue was revolutionised. In order to make the modifications through which it passed intelligible, we must first consider the change in the Answer, and then that which took place in the construction of the Fugue founded upon it—the modern Tonal Fugue.

The elements which enter into the composition of this noble Art-form are of two classes; the one, comprising materials essential to its existence; the other consisting of accessories only. The essential elements are (1) The Subject, (2) The Answer, (3) The Counter-Subject, (4) The Codetta, (5) The Free Part, (6) The Episode, (7) The Stretto, and (8) The Pedal-Point, or Organ-Point. The accessories are, Inversions of all kinds, in Double, Triple, or Quadruple Counterpoint; Imitations of all kinds, and in all possible Intervals, treated in Direct, Contrary, or Retrograde Motion, in Augmentation, or Diminution; Modulations; Canonic passages; and other devices too numerous to mention.

Among the essential elements, the first place is, of course, accorded to the Subject; which is not merely the Theme upon which the Composition is formed, but is nothing less than an epitome of the entire Fugue, which must contain absolutely nothing that is not either directly derived from, or at least more or less naturally suggested by it.

The qualities necessary for a good Subject are both numerous and important. Cherubini has been laughed at for informing his readers that 'the Subject of a Fugue ought neither to be too long, nor too short': but, the apparent Hibernianism veils a valuable piece of advice. The great point is, that the Subject should be complete enough to serve as the text of the discourse, without becoming wearisome by repetition. For this purpose, it is sometimes made to consist of two members, strongly contrasted together, and adapted for separate treatment; as in the following Subject, by Telemann, in which the first member keeps up the dignity of the Fugue, while the second provides perpetual animation.

First Member. Second Member.

Sometimes the construction of the Subject is homogeneous, as in the following by Kirnberger; and the contrast is then produced by means of varied Counterpoint.

Many very fine Subjects—perhaps, the finest of all—combine both qualities; affording sufficient variety of figure when they appear in complete form; and, when separated into fragments, serving all necessary purposes, for Episodes, Stretti, etc., as in the following examples—

Frescobaldi.

'Preserve him for the glory of Thy name.' Handel.

From the Sonata in A. Padre Martini.

Mendelssohn (Op. 35, No. 4).

Sometimes, the introduction of a Sequence, or the figure called Rosalia, affords opportunities for very effective treatment.

Eberlin.

![{ \relative b' { \key e \minor \time 4/4

r8 b c e, dis ais' b d, | cis gis' a c, b g' fis e |

dis c' b a g8.[ fis16 e8] } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/7/n7cavak3wn3a8suq145we1dsrvcli1z/n7cavak3.png)

Sebastian Bach constantly made use of this device in his Pedal Fugues, the Subjects of which are among the longest on record. There are few Subjects in which this peculiarity is carried to greater excess than in that of his Pedal-Fugue in E Major.

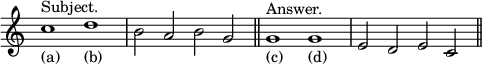

Very different from these are the Subjects designed by learned Contrapuntists for the express purpose of complicated devices. These are short, massive, characterised by extremely concordant Intervals, and built upon a very simple rhythmic foundation. Two fine examples are to be found in Bach's 'Art of Fugue'; and the 'Et vitam' of Cherubini's 'Credo' in G for 8 voices.

J. S. Bach.

Cherubini.

Next in importance to the Subject is the Answer; which, indeed, is neither more nor less than the Subject itself, presented from a different point of view. We have already said that the Tonal Answer must accommodate itself, not to the Intervals of the Subject, but, to the organic constitution of the Scale. The essence of this accommodation consists in answering the Tonic by the Dominant, and the Dominant by the Tonic: not in every unimportant member of the Subject—for this would neither be possible nor desirable—but in its more prominent divisions. The first thing is to ascertain the exact place at which the change from Real to Tonal Imitation must be introduced. For this process there are certain laws. The most important are—

(1) When the Tonic appears in a prominent position in the Subject, it must be answered by the Dominant; all prominent exhibitions of the Dominant being answered in like manner by the Tonic. The most prominent positions possible are those in which the Tonic passes directly to the Dominant, or the Dominant to the Tonic, without the interpolation of any other note between the two; and, in these cases, the rule is absolute.

(2) When the Tonic and Dominant appear in less prominent positions, the extent to which Rule 1 can be observed must be decided by the Composer's musical instinct. Beginners, who have not yet acquired this faculty, must carefully observe the places in which the Tonic and Dominant occur; and, in approaching or quitting those notes, must treat them as fixed points to which it is indispensable that the general contour of the passage should accommodate itself.

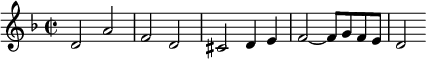

(a) Dominant, answered by Tonic, at (c).

(b) Dominant, answered by Supertonlc, at (d).

(3) The observance of Rules 1 and 2 will ensure compliance with the next, which ordains that all passages formed on a Tonic Harmony, in the Subject, shall be formed upon a Dominant Harmony in the Answer, and vice versâ.

(4) The Third, Fourth, and Sixth of the Scale should be answered by the Third, Fourth, and Sixth of the Dominant, respectively.

(a) Sixth of Tonic. (b) Third of Tonic. (c) Fourth of Tonic.

(d) Sixth of Dominant (e) Third of Dominant.

(f) Fourth of Dominant.

(5) The Interval of the Diminished Seventh, whether ascending or descending, should be answered by a Diminished Seventh.

(6) As a general rule, all Sevenths should be answered by Sevenths; but a Minor Seventh, ascending from the Dominant, is frequently answered by an ascending Octave; in which case, its subsequent descent will ensure conformity with Rule 4, by making the Third of the Dominant answer the Third of the Tonic.

(7) The most difficult note of the Scale to answer is the Supertonic. It is frequently necessary to reply to this by the Dominant; and when the Tonic is immediately followed by the Supertonic, in the Subject, it is often expedient to reiterate, in the Answer, a note, which, in the original idea, was represented by two distinct Intervals; or, on the other hand, to answer, by two different Intervals, a note which, in the Subject, was struck twice. The best safeguard is careful attention to Rule 3, neglect of which will always throw the whole Fugue out of gear.

(a) Tonic, answered by Dominant, at (c).

(b) Supertonic, answered by Dominant, at (d).

Simple as are the foregoing Rules, great judgment is necessary in applying them. Of all the qualities needed in a good Tonal Subject, that of suggesting a natural and logical Tonal Answer is the most indispensable. But some Subjects are so difficult to manage that nothing but the insight of genius can make the connection between the two sufficiently obvious to ensure its recognition. The Answer is nothing more than the pure Subject, presented under another aspect: and, unless its effect shall exactly correspond with that produced by the Subject itself, it is a bad answer, and the Fugue in which it appears a bad Fugue. A painter may introduce into his picture two horses, one crossing the foreground, exactly in front of the spectator, and the other in such a position that its figure can only be truly represented by much foreshortening. An ignorant observer might believe that the proportions of the two animals were entirely different; but they are not. True, their actual measurements differ; yet, if they be correctly drawn, we shall recognise them as a well-matched pair. The Subject and its Answer offer a parallel case. Their measurement (by Intervals) is different, because they are placed in a different aspect; yet, they must be so arranged as to produce an exactly similar effect. We have shown the principle upon which the arrangement is based to be simply that of answering the Tonic by the Dominant, and the Dominant by the Tonic, whenever these two notes follow each other in direct succession; with the farther proviso, that all passages of Melody formed upon the Tonic Harmony shall be represented by passages formed upon the Dominant Harmony, and vice versâ. Still, great difficulties arise, when the two characteristic notes do not succeed each other directly, or, when the Harmonies are not indicated with inevitable clearness. The Subject of Handel's Chorus, 'Tremble, guilt,' shows how the whole swing of the Answer sometimes depends on the change of a single note. In this case, a perfectly natural reply is produced, by making the Answer proceed to its second note by the ascent of a Minor Third, instead of a Minor Second, as in the Subject—i.e. by observing Rule 4, with regard to the Sixth of the Tonic.

The Great Masters frequently answered their Subjects in Contrary Motion, giving rise to an apparently new Theme, described as the Inverted Subject (Inversio; Rivolta, Rivolzimento; Umkehrung). This device is usually employed to keep up the interest of the Composition, after the Subject has been discussed in its original form: but some Masters bring in the Inverted Answer at once. This was a favourite device with Handel, whose Inverted Answers are so natural, as to be easily mistaken for regular ones. The following example is from Cherubini's 'Credo' already mentioned.

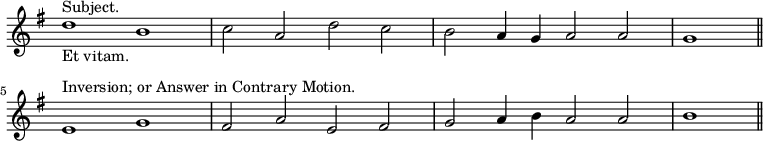

Another method of answering is by Diminution, in which each note in the Answer is made half the length of that in the Subject. This, when cleverly done, produces the effect of a new Subject, and adds immensely to the spirit of the Fugue; as in Bach's Fugue in E, No. 33 of the XLVIII, bars 26–30; in the Fugue in C♯ minor, No. 27 of the same set; and, most especially, in Handel's Chorus, 'Let all the Angels.'

![{ \relative e'' { \key d \major \time 4/4

<< { r2^"Subject." r4 e | a e fis e8 d\noBeam | cis } \\

{ r2 r8 d,_"Answer, by diminution" a'\noBeam e |

fis e16 d cis8 b16 cis d8[ fis] gis8. gis16\noBeam | a2 } >> } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/6/0/60ca5il2qf27qa0q1dxlf9cpw2s1mhu/60ca5il2.png)

Allied to this, though in the opposite direction, is a highly effective form of treatment by Augmentation, in which each note in the Answer is twice the length of that in the Subject, or in Double Augmentation, four times its length. The object of this is, to give weight to massive passages, in which the lengthened notes produce the effect of a Canto fermo. See Bach's Fugue in D♯ minor, no. 8, in the XLVIII, and many other celebrated instances.

Cherubini. 'Et vitam.'

By these and similar expedients, the one Subject is made to produce the effect of several new ones; though the new Motivo is simply a modified form of the original.

But a good Subject must not only suggest a good Answer: it must also suggest one or more subsidiary Themes so constructed as to move against it, in Double Counterpoint, as often as it may appear.[3] These secondary Themes are called Counter-Subjects (Contra-Subjectum; Contra-Tema; Contra-subjekt; Contre-sujet). The Counter-Subject or Counter-Subjects, however numerous they may be, must not only move in Double Counterpoint with the Subject, but all must be capable of moving together, in Triple, Quadruple, or Quintuple Counterpoint, as the case may be. Moreover, after the Subject has once been proposed, it must nevermore be heard, except in company with at least one of its Counter-Subjects. The Counter-Subjects usually appear, one by one, as the Fugue develops; as in Bach's Fugue in C♯ Minor—No. 4 of the XLVIII. Less frequently, one, two, or even three Counter-Subjects appear with the Subject, when first proposed, the Composition leading off, in two, three, or four Parts, at once. It was an old custom, in these cases, to describe the Fugue as written upon two, three, or four Subjects. These names have sometimes been erroneously applied even to Fugues in which the Counter-Subjects do not appear until the middle of the Composition, or even later. For instance, in Wesley and Horn's edition of Bach's XLVIII, the Fugue in C♯ minor is called a 'Fugue on 3 Subjects,' although the real Subject starts quite alone, the entrance of the first Counter-Subject taking place at bar 35, and that of the second at bar 49. Cherubini very justly condemns this nomenclature, even when the Subject and CounterSubjects begin together. 'A Fugue,' he says, 'neither can nor ought to have more than one principal Subject for its exposition. All that accompanies this Subject is but accessory, and neither can nor ought to bear any other name than that of Counter-Subject. A Fugue which is called a Fugue on two Subjects, ought to be called a Fugue on one Subject, with one Counter-Subject,' etc. etc. It is highly desirable that the nomenclature thus recommended should be adopted: but there is no objection to the terms Single and Double Fugue, as applied respectively to Fugues in which the principal Counter-Subject appears after or simultaneously with the Subject; for, when the two Motivi begin together, the term 'Double' is surely not out of place. When two Counter-Subjects begin together with the Subject, the Fugue may fairly be called Triple; when three begin with it, it may be called Quadruple; the number of possible Counter-Subjects being only limited by that of the Parts, with, of course, the necessary reservation of one Part for the Subject. A Septuple Fugue, therefore, is a Fugue in seven Parts, written upon a Subject, and six Counter-Subjects, all beginning together.

The Old Masters never introduced a Counter-Subject into their Real Fugues. Each Part, after it had replied to the Subject, was free to move wherever it pleased, on the appearance of the Subject in another Part. But this is not the case in the modern Tonal Fugue. Wherever the Subject appears, one Part, at least, must accompany it with a Counter-Subject; and those Parts only which have already performed this duty become free—that is to say, are permitted, for the moment, to fill up the Harmony by unfettered Counterpoint.

When the Subject and Counter-Subject start together, the Theme is called a Double-Subject; as in the last Chorus of Handel's 'Triumph of Time and Truth,' based on the Subject of an Organ Concerto of which it originally[4] formed the concluding Movement; in the 'Christe' of Mozart's Requiem; and in the following from Haydn's 'Creation.'

It is very important that the Subject and Counter-Subject should move in different figures. A Subject in long-sustained notes will frequently stand out in quite a new aspect, when contrasted with a Counter-Subject in Quavers or Semiquavers. In Choral Fugues the character of the Counter-Subject is usually suggested by a change in the feeling of the words. For instance, the words of the Chorus, 'Let old Timotheus,' in 'Alexander's Feast,' consist of four lines of Poetry each sung to a separate Motivo.

In order that the Subject may be more naturally connected with its first Counter-Subject, it is common to join the two by a Codetta (Fr. Queue; Germ. Nachsatz), which facilitates the entrance of the Answer, by carrying the leading Part to a note in harmonious continuity with it. The following Codetta is from the celebrated Fugue called 'The Cat's Fugue,' by D. Scarlatti.

The alternation of the Subject with the Answer—called its Repercussion (Lat. Repercussio; Ital. Repercussione; Germ. Wiederschlag) is governed by necessary, though somewhat elastic laws. Albrechtsberger gives twenty-four different schemes for a Fugue in four Parts only, showing the various order in which the Voices may consistently enter, one after the other. The great desideratum is, that the Answer should follow the Subject, directly; and be followed, in its turn, by an immediate repetition of the Subject, in some other Part: the process being continued, until all the Parts have entered, in turn, with Subject and Counter-Subject, alternately, and thus become entitled to continue, for a time, as Free Parts. But the regularity of this alternation is not always possible, in Choral Fugues, the management of which must necessarily conform to the compass of the Voices employed. For instance, in Brahms's 'Deutsche Requiem,' there are two Subjects, each embracing a range of no less than eleven notes—a fatal hindrance to orthodox fugal management.

When the Subject has been thus clearly set forth, so as to form what is called the Exposition of the Fugue, the order of its Repercussion may be reversed; the Answer being assigned to the Parts which began with the Subject, and vice versâ: after which the Fugue may modulate at pleasure. But, in common language, the term Subject is always applied, whether accurately or not, to the transposed Theme, even though it may appear in the aspect proper to the Answer.

As the Fugue proceeds, the alternation of Subject and Answer is frequently interrupted by Episodes (Ital. Andamenti; Fr. Divertissements), founded on fragments of the Subject, or its Counter-Subjects, broken up, in the manner explained on page 135; on fragments of contrapuntal passages, already presented, or on passages naturally suggested by these. Great freedom is permitted in these accessory sections of the Fugue, during the continuance of which almost all the Parts may be considered as Free, to a certain extent. Nevertheless, the great Fuguists are always most careful to introduce no irrelevant idea into their Compositions; and every idea not naturally suggested by the Subject, or by the contrapuntal matter with which it is treated, must necessarily be irrelevant. It is indeed neither possible nor desirable, that every Part should be continuously occupied by the Subject. When it has proposed this, or the Answer, or one of the Counter-Subjects deduced from them, it may proceed in Single or Double Counterpoint with some other Part. But, after a long rest, it must always re-enter with the Subject, or a Counter-Subject; or, at least, with a contrapuntal fragment with which one or the other of them has been previously accompanied, and which may, therefore, be fairly said to have been suggested by the Subject, in the first instance. And thus it is, that even the Episodes introduced into a really good Fugue form consistent elements of the argument it sets forth. In no Fugue of the highest order is a Part ever permitted to enter, without having something important to say.

After the Exposition has been fully carried out, either with or without the introduction of Episodes, the subsequent conduct of the Fugue depends more on the imagination of the Composer than on any very stringent rule of construction; though the great Fuguists have always arranged their plans in accordance with certain well-recognised devices, which are universally regarded as common property, even when traceable to known Masters. And here it is that the ingenious Devices (Fr. Artifices; Germ. Kunsteleien) described at page 135 as accessory elements of the Fugue, are first seriously called into play. The Composer may modulate at will, though only to the Attendant Keys of the Scale in which his Subject stands. He may present his Subject, or Counter-Subject, upside-down—i.e. inverted by Contrary Motion; or backwards, in 'Imitatio cancrizans'; or, 'Per recte et retro'—half running one way, and half the other; or, by single or double Augmentation, in notes twice, or four times, as long as those in the original; or by Diminution, in notes half the length. Or, he may introduce a new Counter-Subject, or even a Canto fermo. In short, he may exercise his ingenuity in any way most congenial to his taste, provided only that he never forgets his Subject. The only thing to be desired is, that the Artifices should be well chosen: not only suggested by the Subject, but in close accordance with its character and meaning. It is quite possible to introduce too many Devices; and the Fugue then becomes a mere dry exhibition of learning and ingenuity. But the Great Masters never fall into this error. Being themselves intensely interested in the progress of their work, they never fail to interest the listener. Among the most elaborate Fugues on record are those in Sebastian Bach's 'Art of Fugue,' in which the Subject given on page 136 is treated with truly marvellous ingenuity and erudition. Yet, even these are in some respects surpassed by the 'Et vitam venturi,' which forms the conclusion of Cherubini's Credo, Alla Cappella, for eight Voices, in Double Choir, with a Thorough-Bass. The Subject (quoted on page 136) is developed by the aid of five distinct Counter-Subjects, three of which enter simultaneously with the Subject itself; the First after a Minim-rest; the Second after three Minims; the Third after two bars: the Subject itself occupying three bars and one note of Alla Breve Time. It may therefore justly be called a Quadruple Fugue. The two remaining Counter-Subjects enter at the fifth and sixth bars, respectively; and, because the first proposal of the Subject comes to an end before their appearance, Cherubini, though giving them the title of Counter-Subjects, does not number them, as he did the first three, but calls one l'autre, and the other le nouveau contre-sujet. The Artifices begin at the fourth bar, with an Imitation of the Third Counter-Subject in the Unison, and continue thence to the end of the Fugue, which embodies 243 bars of the finest contrapuntal writing to be found within the entire range of modern Music.

When the capabilities of the Subject have been demonstrated, and its various Counter-Subjects discussed, it is time to bind the various members of the Fugue more closely together, in the form of a Stretto[5] (Lat. Restrictio; Ital. Stretto, Restretto; Germ. Engführung; Fr. Rapprochement), or passage in which the Subject, Answer, and Counter-Subjects, are woven together, as closely as possible, so as to bind the whole into a knot. Aptitude for the formation of an artful Stretto is one of the most desirable qualities in a good Fugal Subject. Some Subjects will weave together, with marvellous ductility, at several different distances. Others can with difficulty be tortured into any kind of Stretto at all. Sebastian Bach's power of intertwining his Subject and Counter-Subjects seems little short of miraculous. The first Fugue of the XLVIII, in C major, contains seven distinct Stretti, all differently treated, and all remarkable for the closeness of their involutions. Yet, there is nothing in the Subject which would lead us to suppose it capable of any very extraordinary treatment. The secret lies rather in Bach's power over it. He just chose a few simple Intervals, which would work well together; and, this done, his Subject became his slave. Almost all other Fugues contain a certain number of Episodes; but here there is no Episode at all: not one single bar in which the Subject, or some portion of it, does not appear. Yet, one never tires of it, for a moment; though, as the Answer is in Real Fugue, it presents no change at all, except that of Key, at any of its numerous recurrences. Some wonderfully close Stretti will also be found in Bach's 'Art of Fugue'; in Handel's 'Amen Chorus'; in Cherubini's 'Et vitam,' already described; in the 'Et vitam' of Sarti's 'Credo,' for eight Voices, in D; and in many other great Choral Fugues by Masters of the 18th century, and the first half of the 19th, including Mendelssohn and Spohr. Some of these Stretti are found on a Dominant, and some on a Tonic Pedal. In all, the Subject is made the principal feature in the contrapuntal labyrinth. The following example, from the 'Gloria' of Purcell's English 'Jubilate,' composed for S. Cecilia's Day, 1694, is exceptionally interesting. In the first place, it introduces a new Subject—a not uncommon custom with the earlier Fuguists, when new words were to be treated—and, without pausing to develop its powers by the usual process of Repercussion, presents it in Stretto at once. Secondly, it gives the Answer, by Inversion, with such easy grace, that one forgets all about its ingenuity, though it really blends the learning of Polyphony with the symmetry of modern Form in a way which ought to make us very proud of our great Master, and the School of which he was so bright an ornament. For, when Purcell's 'Te Deum' and 'Jubilate' were written, Sebastian Bach was just nine years old.

With the Stretto or Organ-Point the Fugue is generally brought to a conclusion, and, in many examples, by means of a Plagal Cadence.

Having now traced the course of a fully developed modern Tonal Fugue, from its Exposition to its final Chord, it remains only to say a few words concerning some well-recognised exceptions to the general form.

We have said that the modern Fugue sprang into existence through the recognition of its Tonal Answer, as an inevitable necessity. Yet there are Subjects—and very good ones too—which, admitting of no natural Tonal Answer at all, must necessarily be treated in Real Fugue: not the old Real Fugue, formed upon a few slow notes treated in close Imitation; but, a form of Composition corresponding with the modern Tonal Fugue in every respect except its Tonality. Such a case is Mendelssohn's Fugue in E minor (op. 35, no. 1), in which the Answer is the Subject exactly a fifth higher.

Again, a Fugue is sometimes written upon, or combined with, a Canto fermo; and the resulting conditions very nearly resemble those prevailing on board a Flag-Ship in the British Navy; the functions of the Subject being typified by those of the Captain, who commands the ship, and the privileges of the Canto fermo, by those of the Admiral, who commands the Captain. Sometimes the Subject is made to resemble the Canto fermo very closely only in notes of shorter duration; sometimes it is so constructed as to move in Double Counterpoint against it. In neither case is it always easy to determine which is the real Subject; but attention to the Exposition will generally decide the point. Should the Canto fermo pass through a regular Exposition, in the alternate aspects of Dux and Comes, it may be fairly considered as the true Subject, and the ostensible Subject must be accepted as the principal Counter-Subject. Should any other Theme than the Canto fermo pass through a more or less regular Exposition, that Theme is the true Subject, and the Canto fermo merely an adjunct. Examples of the first method are comparatively rare in Music later than the 17th century. Instances of the second will be found in Handel's 'Utrecht Te Deum and Jubilate,' 'Hallelujah Chorus,' 'The horse and his rider,' Funeral, and Foundling Anthems; and in J. S. Bach's 'Choral Vorspiele.'

[ W. S. R. ]

[ M. ]

- ↑ Those who wish to trace the relation between the two will do well to study the 'Messa Canonica,' edited by La Fage, and by him attributed to Palestrina, or the 'Missa Canonica' of Fux, side by side with Palestrina's 'Missa ad Fugam'; taking the two first-named works as examples of Limited, and the third of Unlimited Real Fugue.

- ↑ The 'Answer' here might with equal propriety be considered as the 'Subject'; in which case the answer would be by Augmentation.

- ↑ See Counter-Subject, vol. 1. p. 400.

- ↑ See the original MS., in the British Museum, George III. MSS. 310 [274. d.]

- ↑ From stringere, to bind.