A Dictionary of Music and Musicians/Welsh Music

WELSH MUSIC. With regard to the source whence the ancient Britons derived their music and musical instruments, the general belief in the Principality is that they were brought from the East, either by the inhabitants in their original migration, or by the Phoenicians, who, as is well known, had commercial intercourse with Britain from the earliest times. Of this however there is no historical proof, nor do the arguments sometimes adduced from an alleged similarity of musical terms in Hebrew and Welsh bear the test of examination.

In ancient Welsh works, 'to play upon the harp' is expressed 'to sing upon the harp'—Canu ar y Delyn. The same expression is used in regard to the Crwth, an old Welsh instrument, which was so popular in Britain in olden times as to have been mistaken, by historians of the 6th century, for its national instrument. [Crwth.]

The harp, of all instruments, is the one which has been held in the most general esteem, and has for ages been the companion of Prophet, King, Bard, and Minstrel. In the 7th century, according to the Venerable Bede, it was so generally played in Britain that it was customary to hand it from one to another at entertainments; and he mentions one who, ashamed that he could not play upon it, slunk away lest he should expose his ignorance. In such honour was it held in Wales that a slave might not practise upon it; while to play upon the instrument was an indispensable qualification of a gentleman. The ancient laws of Hywel Dda mention three kinds of harps:—the harp of the King; the harp of a Pencerdd, or master of music; and the harp of a Nobleman. A professor of this instrument enjoyed many privileges; his lands were free, and his person sacred.

With regard to the antiquity of the Welsh music now extant, it is difficult to form a conjecture, excepting when history and tradition coincide, as in the case of the plaintive air 'Morva Rhuddlan' (Rhuddlan Marsh). 'At this time,' says Parry in his 'Royal Visits,' 'a general action took place between these parties, upon Rhuddlan Marsh, Flintshire. The Welsh, who were commanded in this memorable conflict by Caradoc, King of North Wales, were defeated with dreadful slaughter, and their leader was killed on the field. All who fell into the hands of the Saxon Prince were ordered to be massacred. According to tradition, the Welsh who escaped the sword of the conqueror, in their precipitous flight across the marsh, perished in the water by the flowing of the tide.' Tradition says that the plaintive melody, 'Morva Rhuddlan,' was composed by Caradoc's Bard immediately after the battle, a.d. 795.

Morva Rhuddlan. (The Plain of Rhuddlan.)

![{ \relative g' { \key g \minor \time 3/4 \tempo "Mournfully." \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

g4 g bes8 d | c4 c bes | a a8[ bes a g] | d'4 d, r | %end line 1

g4 g8[ a bes d] | c4 ees8[ d c bes] | a4 g fis |

g2. \bar ":|." d'4 d8[ ees f d] | %end line 2

c4 c8[ d ees c] | bes4 bes a | a bes r |

d d8 ees f ees16 d | c4 c8 d ees d16 ees | %end line 3

bes8 ees d c bes a | a4 bes c\turn |

d bes8[ c ees bes] | c bes a bes c a | %end line 4

bes8. a16 g8 bes a g | fis4 d r | g g8 a bes d |

c8. d16 ees8 d c bes | a4 g fis | g2. \bar ":|." } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/c/q/cqb7fw99lie6y4egro6cgmbs0d30osa/cqb7fw99.png)

One of the finest melodies of this class is Davydd y Garreg Wen—David of the White Rock; and although there is no historical account concerning it, it is, nevertheless, supposed to be very ancient. Tradition says that a Bard of this name, lying on his deathbed, called for his harp, composed this touching melody, and desired that it should be played at his funeral.

Davydd y Garreg Wen. (David of the White Rock.)

The following is also one of the most pathetic melodies, and supposed to be very ancient.

Torriad y Dydd. (The Dawn of Day.)

![{ \relative g' { \key g \minor \time 4/4 \partial 8 \tempo "Andante."

g8 | g d d bes' bes a r a | g bes a g fis4.\trill g8 | %eol1

d8.[ ees16 c8. d16] bes8.[ c16 a8. bes16] |

g8 g' a fis g4. \bar ":|.|:" d'8 | \break %end line 2

d bes bes d d c4 c8 | d bes bes d c4.\trill d8 |

bes8.[ c16 a8. bes16] g8. a16 f8.[ a16] | %end line 3

bes8.[ c16 d8 c] bes4. bes16 c | d8 bes c d ees d4 c8 |

bes8 a d g, fis4.\trill g8 | %end line 4

d8.[ ees16 c8. d16] bes8.[ c16 a8. bes16] | g8 g' a fis g4. \bar ":|." } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/0/6/06n2jnceiq6zkr90x8b7ga64r4oewjb/06n2jnce.png)

There is no denying that Welsh music is more artistic than either that of the Scotch or the Irish, and on that account it may, to a superficial observer, appear more modern; but to those who are acquainted with the harp, the national instrument of Wales, with its perfect diatonic scale, the apparent inconsistency disappears. This is admitted by the most eminent writers on music, among others, by Dr. Crotch. In the first volume of his Specimens[1] of the various styles of music, referred to in his course of lectures, he writes as follows:—

British and Welsh music may be considered as one, since the original British music was, with the inhabitants, driven into Wales. It must be owned that the regular measure and diatonic scale of the Welsh music is more congenial to the English taste in general, and appears at first more natural to experienced musicians, than those of the Irish and Scotch. Welsh music not only solicits an accompaniment, but, being chiefly composed for the harp, is usually found with one; and, indeed, in harp tunes, there are often solo passages for the bass as well as for the treble. It often resembles the scientific music of the 17th and 18th centuries, and there is, I believe, no probability that this degree of refinement was an introduction of later times.… The military music of the Welsh seems superior to that of any other nation.… In the Welsh marches, 'The March of the men of Harlech,' 'Captain Morgan's March,' and also a tune called 'Come to Battle,' there is not too much noise, nor is there vulgarity nor yet misplaced science. They have a sufficiency of rhythm without its injuring the dignified character of the whole.

We give the melodies of the three marches mentioned.

Rhyfelgyrch Gwyr Harlech. (March of the Men of Harlech.)[2]

![{ \relative b' { \key bes \major \time 4/4 \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

bes8.[ a16 g8 a] bes c d bes | ees d c bes a g a f | %end line 1

bes8.[ a16 g8 a] bes c d f |

f16 d8. c8.\turn bes16 bes2 \bar ":|.|:"

c8.[ bes16 a8. bes16] c8 c r4 | %end line 2

f8.[ ees16 d8. ees16] f8 f r4 |

f8.[ ees16 d8. ees16] f8.[ ees16 d8. ees16] %end line 3

f8.[ ees16 d8. ees16] f8 f r8 d |

ees8.[ g16 f8. f16] ees8.[ ees16 d8. d16] | %end line 4

c8 ees16 d c8 bes a g a f | bes8.[ a16 g8 a] bes c d f | %end line 5

f16 d8. c8.\turn bes16 bes2 \bar ":|." } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/k/6/k6z6nvp7z8zu8ymjmxk8g456lqqgut3/k6z6nvp7.png)

Rhyfelgyrch Cadpen Morgan. (Captain Morgan's March.)

![{ \relative f' { \key bes \major \time 4/4

\repeat volta 2 { f4 bes8. bes16 bes4 f | bes8.[ c16 d8. c16] bes2 |

ees4 ees d d | c8.[ bes16 c8. d16] c2 }

\repeat volta 2 { f4 f8. ees16 d4 bes | ees8.[ f16 ees8. d16] c2 |

bes8 d c bes a4 bes8 c | d4 c bes2 } } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/p/bpbhn2e35b9jgw73sudxmx3z1gb82lh/bpbhn2e3.png)

Dewch i'r Frwydr. (Come to Battle.)

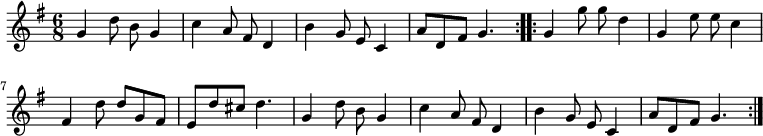

The Welsh are specially rich in Pastoral Music, which is graceful, melodious, and unaffected. It is chiefly written for the voice, and the subject of the words is generally taken from the beauties of Nature, with an admixture of Love. The collection is so numerous, that it is no easy matter to make a selection; however, the following specimens will serve to show the natural beauty of these melodies:—

Codiad yr Hedydd. (The Rising of the Lark.)

![{ \relative c'' { \time 2/4 \key c \major \tempo "Moderato."

\repeat volta 2 {

c4 g8. f16 | e8[ c' g e] | f8.[ g16 a8 b] | c[ b c d] | %eol1

e16 c8. g8. b16 | c2 }

\repeat volta 2 {

e8.[ c16 c8 e-.] | d8.[ c16 b8 d-.] | c8.[ b16 a8 c-.] | %eol2

b8 a16 b g4 | e'8.[\turn d16 c8 e] | d8.[\turn c16 b8 d] |

c8.[\turn b16 a8 c] | b8[ g g] r16 e | %end line 3

f8[ g a b] | c[ b c d] | e c g'8. b,16 | c2 } } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/4/7/470d0os5636l5k0d3b1mopubdxusbw8/470d0os5.png)

Bugeilio'r Gwenith Gwyn. (Watching the Wheat.)

Mentre Gwen. (Venture Gwen.)

The following melody has the peculiarity of each part ending on the fourth of the key.

Dadle Dau. (Flaunting Two.)

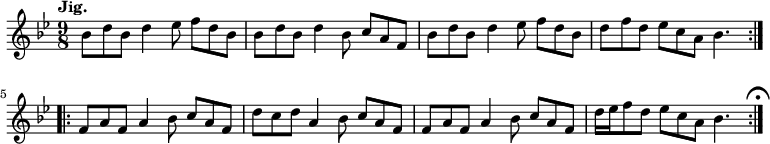

Of the Dance Music of the Welsh, the Jig appears to be the favourite. Of these there are many interesting examples, from which the following are selected:—

Heffedd Modryb Marged. (Aunt Margaret's Favourite.)

Gyrru'r Býd o'm Blaen. (Drive the World before us.)

Tri Hauner Tón. (Three half Tunes.)

The most remarkable feature in connection with Welsh music is that of Penillion singing,—singing of epigrammatic stanzas, extemporaneous or otherwise, to the accompaniment of one of the old melodies, of which there are many, very marked in character, expressly composed or chosen on account of their adaptability for the purpose, and played upon the harp. This practice is peculiar to the Welsh, and is said to date from the time of the Druids, who imparted their learning orally, through the medium of Penillion. The word Penill is derived from Pen, a head; and because these stanzas flowed extempore from, and were treasured in the head, without being committed to paper, they were called Penillion. Many of the Welsh have their memories stored with hundreds of them; some of which they have always ready in answer to almost any subject that can be proposed; or, like the Improvísatore of Italy, they sing extempore verses; and a person conversant in this art readily produces a Penill apposite to the last that was sung. But in order to be able to do this, he must be conversant with the twenty-four metres of Welsh poetry. The subjects afford a great deal of mirth. Some of these are jocular, others farcical, but most of them amorous. It is not the best vocalist who is considered to excel most in this style of epigrammatical singing; but the one who has the strongest sense of rhythm, and can give most effect and humour to the salient points of the stanza—not unlike the parlante singing of the Italians in comic opera. The singers continue to take up their Penill alternately with the harp without intermission, never repeating the same stanza (for that would forfeit the honour of being held first in the contest), and whichever metre the first singer starts with must be strictly adhered to by those who follow. The metres of these stanzas are various; a stanza containing from three to nine verses, and a verse consisting of a certain number of syllables, from two to eight. One of these metres is the Triban, or triplet; another, the Awdl Gywydd, or Hén Ganiad,—the ode-measure or the ancient strain; another, what in English poetry would be called anapæstic.

There are two kinds of Penillion singing; the most simple being where the singer adapts his words to the melody, in which case words and music are so arranged as to allow of a burden, or response in chorus, at the end of each line of the stanza, as in the following example:—

Nos Galan. (New Year's Eve)

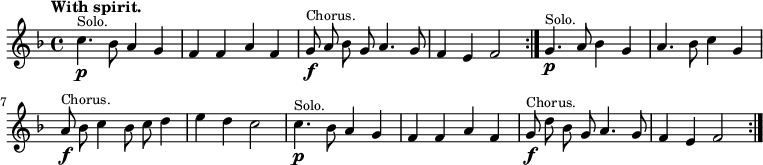

Hob y Deri Danno. (Away, my herd, to the Oaken Grove.)

As sung in North Wales.

![{ \relative b' { \key bes \major \time 2/4 \tempo "Cheerfully." \autoBeamOff

\repeat volta 2 {

bes8\p^\markup \small "Solo" bes d8. c16 | bes8 f g f |

g16\f^\markup \small "Burden" a g f g8 f | bes4\p d | c2 }

ees8^\markup \small "Solo" ees g g16 f | ees8 c d c |

f8.\f^\markup \small "Burden" f16 f8 e | f2 |

bes,8^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes16[ c] d[ ees] |

f8 f16[ ees] d8 c | bes4 c | d8 d c4 |

f8 f16 ees d8 c | d8. c16 bes4 |

bes4\p^\markup \small "Burden" d | bes2 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/b/1/b1sde2t4x2olainrhbb8u7dcdf8zqri/b1sde2t4.png)

Hob y Deri Dando. (Away, my herd, under the Green Oak.)

The same song as sung in South Wales.

![{ \relative f' { \key bes \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Cheerfully." \autoBeamOff

f4^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes c8[ d] | ees4 d c bes |

bes8^\markup \small "Burden" d c bes c4 f, | R1 |

f4^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes c8[ d] | ees4 d c bes |

f'8^\markup \small "Burden" g f g f4 f, | R1 \bar "||"

f'4^\markup \small "Solo" f8. f16 f4 ees8[ d] | ees4 4 4 d8[ c] |

d4.^\markup \small "Burden" ees8 d4 c8[ bes] | c2 r |

f,4^\markup \small "Solo" bes bes c8[ d] | ees4 d c bes |

f bes8.[ c16] bes2 | a8. bes16 c8. d16 c2 |

bes4 f'8. g16 f4. ees8 |

d4.^\markup \small "Burden" c8 bes2 \bar "||" \mark \markup { \musicglyph "scripts.ufermata" } } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/n/c/ncqvcbmqw789vsa4do93ydek22yye3w/ncqvcbmq.png)

The most difficult form of Penillion singing is where the singer does not follow the melody implicitly, but recites his lines on any note that may be in keeping with the harmony of the melody, which renders him indifferent as to whether the harper plays the air or any kind of variation upon it, as long as he keeps to the fundamental harmony. In this style of Penillion singing there is no burden or chorus, the singer having the whole of the melody to himself, first and second part repeated. What renders it more difficult, is the rule that he must not begin with the melody, but, according to the length of the metre of his stanza, must join the melody at such a point as will enable him to end with it.

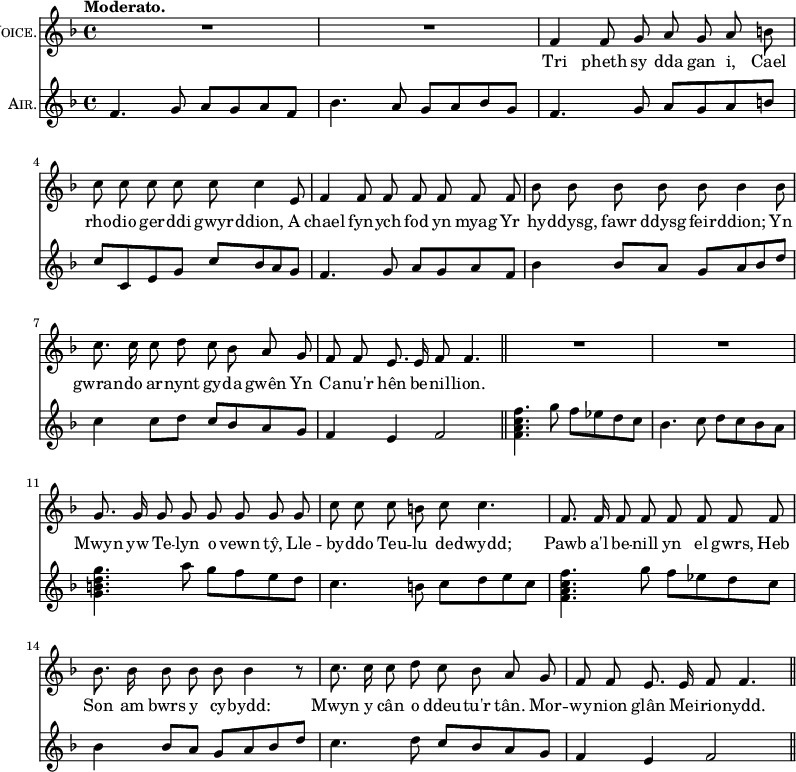

The following examples admit of the introduction of two of the most famous melodies in connection with this style of singing.

Air. 'Pen Rhaw.' (The name of a Harper.)[3] Penillion.

Air. 'Serch Hudol.' (Love's Fascination.) Penillion.

![{ << \new Staff \with {instrumentName = \markup { \caps "Voice." } } \relative d'' { \key f \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Spirited." \autoBeamOff \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

R1 R | d8. cis16 d8 e d d d d | d d cis cis d d4 r8 |

f f f e d c bes[ a] | bes4 bes8 bes c c c c |

f, f f f bes bes bes8. bes16 | c8 c bes8. bes16 a8 a r4 \bar "||"

R1 R | d8 d d d cis cis cis cis | d16 d8. cis8 8 d d4 r8 |

f8. f16 f8 e d c bes[ a] | bes4 8 8 c c c16 c8. |

f,8. f16 f8 f bes8. 16 8 8 | c c bes8. bes16 a8 a4. \bar "||" }

\addlyrics { Maen yw llun, a Mwyn yw llais, Y

del -- yn far -- nais ne -- wydd,

Hae -- ddai glod am fod yn fwyn,

Hi y -- dyw llwyn lla -- wen -- ydd:

Fe ddaw'r ad -- ar yn y man, I di wnlo dan ei' -- de -- nydd.

Yma a thraw y Maent yn Sôn, A min -- au'n cys -- on wra -- ndo,

Nas gŵyr un -- dyn yn y -- wlad

Pwy yd -- yw'm Car -- iad et -- to;

Ac nis gyn yn dda fy hun Oes i -- mi un a'l peld -- lo. }

\new Staff \with { instrumentName = \markup { \caps "Air." } } \relative f'' { \key f \major

f4\f f,16 a c f e4 r | d d,16 f a d cis4 r | %eol1

d8. cis16 d8 e f d a' g | f e16 d e8 d16 cis d4 d8 e | %eol2

f[ \tuplet 3/2 { f,16 a c] } f8 e d c bes a |

g bes16 a g8 f e g c e, | %eol3

f a d c bes a g f | e8. f16 g8. e16 f4 r | %eol4

a8 c16 a f8 g a4. a8 | d f e d cis e a cis, | %eol5

d f a d, e a, a' g | f e16 d e8 d16 cis d4 d8 e | %eol6

f[ \tuplet 3/2 { f,16 a c] } f8 e d c bes a |

g bes16 a g8 f e g c e, | %eol7

f a d c bes a g f | e8. f16 g8. e16 f2 } >> }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/5/5/55yyd61r7r8opbim7mggq8mposb88xf/55yyd61r.png)

Until within the present century, very little Welsh music was known beyond the Principality; and even then, for the most part, through an unfavourable medium. For example, the graceful 'Llwyn onn' (The Ash Grove), appeared in a mutilated form as 'Cease your funning,' in Gay's 'Beggar's Opera,' a.d. 1728.

Llwyn onn. (The Ash Grove.)

![{ \relative g' { \key g \major \time 3/4 \tempo "Gracefully."

\repeat volta 2 {

g4 b d | b g g | a8. b16 c4 a | fis d d |

g b8 g a fis | g4 e c | d g fis | g2. }

\repeat volta 2 {

b4 b8 c d e | d4 c b | a8 b c d c[ d] | c4 b a | g8 a b c b[ c] |

b4 a g | fis d' cis | d2. | g4. fis8 e g | d4 b g |

a c8 a b g | a4 fis d | g8.[ a16 b8 g] a fis | g4 e c |

d g fis | g2. } } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/s/7/s7atcvcl68n083kwuqnt0op12qgcwd6/s7atcvcl.png)

Gay's version, as 'Cease your funning.'

The melodious 'Clychau Aberdyfi' (The Bells of Aberdovey) was caricatured in Charles Dibdin's play 'Liberty Hall,' a.d. 1785.

Clychau Aberdyfi. (The Bells of Aberdovey.)

![{ \relative b' { \key g \major \time 4/4 \tempo "Lively." \autoBeamOff \override Score.Rest #'style = #'classical

b8. c16 b8. a16 b8 d d,8.[ c'16] |

b8. c16 b8. a16 b8 d d,\fermata c' | %end line 1

b a c b a d g, b16 g | e8 a d,8. fis16 g8 g r4 | %end line 2

b g d' b8 b | g'4. d8 d4\fermata r8 c | b a c b a d g, b16 g | %e3

e8 a d,8. fis16 g8 g r4 \bar "||"

b8. c16 b8. a16 g8 b d8. d,16 | %end line 4

e8 a fis d d g r4 | b8. c16 b8. a16 g8 b d8. b16 | %end line 5

a8 g fis e d d r4 | c'8 b a g a d d,8.[ c'16] | %end line 6

b8. a16 g8. a16 b8 d d,\fermata c' |

b a c b a d g, b16 a | %end line 7

e8 a d,8. fis16 g8 g r4 | b g d' b8 b | g'4. d8 d4\fermata r8 c |%8

b8 a c b a d g, b16 g | e8 a d,8. fis16 g8 g r4 \bar "||" } }](http://upload.wikimedia.org/score/d/s/ds13qvbfiwx5guh5bagzl64omrff8nk/ds13qvbf.png)

The bold and warlike strain, 'Y Gâdlys' (The Camp), suffered the degradation of being wedded to Tom Durfey's doggrel song 'Of noble race was Shenkin,' introduced into 'The Richmond Heiress,' a.d. 1693.

Y Gâdlys. (The Camp.)

The beautiful little melody, 'Ar hyd y nos' (All through the Night), was introduced into a burlesque, under the title of 'Ah! hide your nose.' It is often known as 'Poor Mary Ann.'

Ar hyd y nos. (All through the Night).

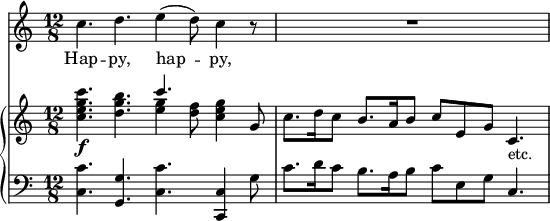

Even Handel was not above introducing the spirited air, 'Codiad yr Haul' (The Rising of the Sun), into 'Acis and Galatea,' as a duet and chorus, under the title of 'Happy, happy we.'

The following is the original air:—

Handel's version is as follows [App. p.816 "first bar-line should be between the second and third sets of triplets, not before the first set"]:—

Happy, happy we. (Duet.)

The opening bar of the chorus imitates the original melody still more closely:—

Handel also turned this air into a gigue ('Suites de Pièces,' 1st collection, p. 43, Leipzig edition).

But it must be admitted that the beauty of the original theme has been greatly enhanced by his masterly treatment.

According to a Welsh manuscript of the time of Charles I, now in the British Museum—which though itself of the 17th century was doubtless copied or compiled from earlier records[4]—Gryffudd ab Cynan, King of North Wales, held a congress, in the nth century, for the purpose of reforming the order of the Welsh bards, and invited several of the fraternity from Ireland to assist in carrying out the contemplated reforms; the most important of which appears to have been the separation of the professions of bard and minstrel—in other words, of poetry and music; both of which had before been united in one and the same person. The next was the revision of the rules for the composition and performance of music. The '24 musical measures' were permanently established, as well as a number of keys, scales, etc.; and it was decreed that henceforth all compositions were to be written in accordance with those enactments; and that none but those who were conversant with the rules should be considered thorough musicians, or competent to undertake the instruction of others.

In this manuscript will also be found some of the most ancient pieces of music of the Britons, supposed to have been handed down from the ancient bards. The whole of the music is written for the Crwth, in a system of notation by the letters of the alphabet, with merely one line to divide bass and treble. Dr. Burney, after a life-long research into the musical notation of ancient nations, gives the following as the result:—

It does not appear from history that the Egyptians, Phoenicians, Hebrews, or any ancient people who cultivated the arts, except the Greeks and Romans, had musical characters; and these had no other symbols of sound than the letters of the alphabet, which likewise served them for arithmetical numbers and chronological dates.

The system of notation in the manuscript resembles that of Pope Gregory in the 6th century, and may have found its way into this country when he sent Augustine into Britain to reform the abuses which had crept into the services of the western churches.

St. Gregory's Notation.

A, B, C, D, E, F, G, a, b, c, d, e, f, g, aa, bb, cc, dd, ee, ff, gg.

Notation in the Ancient Welsh Manuscript.

cc dd ee ff g1 a1 b1 c1 d1 e1 f1 g̅ a̅ b̅ c̅ d̅ e̅ f̅ g• a• b• c• d• e• f•

A close resemblance to the ancient Welsh notation is to be found in a work entitled Musuryia,[5] seu praxis musicae, illius primo quae Instruments agitur certa ratio, ab Ottomaro Luscinio Argentina duobus Libris absoluta. Argentorati apud Ioannem Schottum, Anno Christi, 1536. The following is a fac-simile of the specimen alluded to, as applied to the keys of the organ (which instrument was invented about the middle of the 7th century), with additional marks for the flats and sharps, in keeping with the rest of the notation:—

The circumstance of Irish names being attached to the 24 musical measures in the British Museum MS. alluded to, has led to the erroneous conclusion that Wales derived the whole of her music from Ireland, at the time of Gryffudd ab Cynan; when, as is alleged, the measures were constructed. Even Welsh chroniclers, such as Giraldus Cambrensis, Caradoc, Powel, and others, have made this statement in their works upon the strength of the circumstance alluded to; it is, therefore, not surprising that Gunn, Walker, Bunting, Sir John Hawkins, and other modern writers, should have been deceived by relying upon such apparently good authority. But, independently of the extreme dissimilarity of the Welsh and Irish music that has been handed down to us, it happens that other parts of the document bear ample testimony to the contrary. The Welsh had their 24 metres (or measures) in poetry, as well as their 24 athletic games; and the following circumstance is in favour of their possessing their musical measures centuries prior to Gryffudd ab Cynan. Among the ancient pieces included in the manuscript, is one bearing the following title, and written in one of the 24 measures–Mac Mun byr—Gosteg yr Halen ('Prelude to the Salt'), and at the end is the following account concerning it: 'Tervyn Gosteg yr Halen, yr hon a vyddid yn ei chanu ovlaen Marchogion Arthur pan roid y Salter a'r halen ar y bwrdd'—'Here ends the Prelude to the Salt, which used to be performed before the Knights of King Arthur, when the Salt-cellar was placed on the table'—that is, if the tradition can be sustained, the middle of the 6th century, when King Arthur is supposed to have flourished. In the manuscript, the notation is as follows:—

Dechre Gosteg yr Halen.

|

Bys hyd y Marc: a'r diwedd yma sy ar ol pob cainc. |

|

Bys y cwbyl o'r diwedd etto hyd yma, a'r ail tro hyd y marc, ac velly tervyn y diwedd. |

The above specimen consists merely of the theme, to which there are twelve variations; and although the counterpoint is very primitive, and the whole is written for the Crwth, it is not without interest, as having been handed down from a remote period, and being thus, perhaps, the most ancient specimen of music in existence. Those who wish to look further into the matter will find the theme and variations, with the 24 musical measures, etc., transcribed into modern notation and published in the second edition of the 'Myvyrian Archæology of Wales.'

It is also asserted that even the keys used in Welsh Music were brought over from Ireland at the same time as the twenty-four measures. Five keys are mentioned in the manuscript:—

- Is-gywair—the low key, or key of C.

- Cras-gywair—the sharp key, or key of G.

- Lleddf-gywair—the flat key, or key of F.

- Go-gywair—the key with a flat or minor third; the remainder of the Scale, in every other respect, being major.

- Bragod-gywair called the minor or mixed key.

A curious circumstance is related by two Welsh historians, Dr. John David Rhŷs and John Rhydderch, as having occurred in the middle of the 7th century: 'King Cadwaladr sat in an Eisteddfod, assembled for the purpose of regulating the bards, and taking into consideration their productions and performances, and of giving laws to music and poetry. A bard who played upon the harp in presence of this illustrious assembly in a key called Is gywair, ar y bragod dannau (in the low pitch and in the minor or mixed key), which displeased them much, was censured for the inharmonious effect he produced. The key in which he played was that of Pibau Morvydd, i.e. "Caniad Pibau Morvydd sydd ar y bragod gywair." (The song of Morvydd's Pipes is in the minor or mixed key.) He was then ordered, under great penalties, whenever he came before persons skilled in the art, to adopt that of Mwynen Gwynedd, "the pleasing melody of North Wales," which the royal associates first gave out, and preferred. They even decreed that none could sing or play with true harmony but with Mwynen Gwynedd, because that was in a key which consisted of notes that formed perfect concords, whilst the other was of a mixed nature.' This incident possibly arose from a general desire to suppress an attempt to introduce into Wales the pentatonic, or so-called Scotch Scale, where the fourth and leading note of the key are omitted, a fact which accounts for the peculiar effect produced upon a cultivated ear by the Scotch bagpipe of the present day, where the music passes from minor to relative major, and back, without the least regard for the tonic and dominant drones of the original key, which continue to sound. The story, if true, would show that the Welsh were already in possession of a Scale or Key, which, by their own showing, consisted of notes that formed perfect concords; whereas the other, which they objected to, was of a mixed nature, neither major nor minor, but a mixture of the two—which is not altogether an inapt way of describing the pentatonic or Scotch Scale.

The 'Caniad Pibau Morvydd' (The Song of Morvydd's Pipes), above alluded to, is also included in the ancient manuscript.

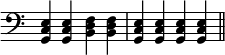

The 'twenty-four measures' consisted of a given number of repetitions of the chords of the tonic and dominant, according to the length of each measure, and are represented by the following marks, 1 standing for the tonic chord, and 0 for the dominant:—

Long Measure (Mac y Mwn Hir.)

111100001010111100001011 or 111 111 111 111 1⋅

or in modern notation

Short Measure (Mac y Mwn Byr.)

11001111 or 111⋅

The positions of the chords are arranged so as to admit of their being played on the open strings of the Crwth.

These measures do not appear in Welsh music after the date to which the manuscript refers, a circumstance which may be considered most fortunate; for, though well adapted to their purpose at that early period, viz. for the guidance of performers on the Harp and Crwth—the latter being used as an accompaniment to the Harp—had such rules remained in force, they would have rendered the national music of Wales intensely monotonous and uninteresting, and thoroughly destroyed all freedom of imagination in musical composition; whereas, it is remarkable for its beauty of melody, richness of harmony and variety of construction.

Printed Collections of Welsh Melodies.

Ancient British Music. John Parry of Rhuabon. Vol. i. 1742.

Welsh, English, and Scotch Airs. John Parry of Rhuabon. Vol. ii. No date.

British Harmony, Ancient Welsh Airs. John Parry of Rhuabon. Vol. iii. 1781.

Relicks of the Welsh Bards. Edward Jones (Bardd y Brenin). Vol. i. 1794.

Bardic Museum. Edward Jones (Bardd y Brenin). Vol. ii. 1802.

Cambro-British Melodies. Edward Jones (Bardd y Brenin). Vol. iii. No date.

Welsh Melodies. John Parry (Bardd Alaw). 1809.

The Welsh Haper. John Parry (Bardd Alaw). Vol. i, 1830; vol. ii, 1848.

Original Welsh Airs, arranged by Haydn and Beethoven. George Thompson, Edinburgh. Vol. i, 1809; vol. ii, 1811; vol. iii, 1814.

British Melodies. John Dovaston, Dublin. Part i, 1817; part ii, 1814.

Welsh Melodies. J. Thompson. 1817.

Cambrian Harmony. Richard Roberta of Caernarvon. 1829.

The Ancient Airs of Gwent and Morganwg. Miss Jane Williams of Aberpergwm. 1844.

The Cambrian Minstrel. John Thomas of Merthyr. 1845.

Welsh National Airs. John Owen (Owain Alaw) of Chester. 1st series, 1860; 2nd series, 1861; 3rd series, 1862; 4th series, 1864

Welsh Melodies. John Thomas (Pencerdd Gwalia) of London. Vols. i and ii, 1862; vol. iii, 1870; vol. iv, 1874.

MS. Collections.

The Welsh manuscript mentioned in the foregoing article as in the British Museum is in Add. MS. 14,905. The writing shows it to be of the date of Charles I. It came to the Museum from the 'Welsh School.' The book contains the name of Lewis Morris 1742, and Richard Morris, Esq., 1771, and the following MSS.

Fol. 3. Cerdd Dannau. Extract from an old Manuscript of Sir Watkin Williams Wynn.

3a. Copy of an order by Elizabeth as to the bestowal of a Silver Harp on the best harper. 1567.

4a. Drawing of the harp (16 strings). Title—'Musica neu Beroriaeth. The following Manuscript is the Musick of the Britains, as settled by a Congress, or Meeting of Masters of Music, by order of Gryffudd ap Cynan, Prince of Wales, about a.d. 1040; with some of the most antient pieces of the Britains, supposed to have been handed down to us from the British Druids; in Two Parts (i.e. Bass and Treble) for the Crwth. This Manuscript was wrote by Robert ap Huw of Bodwigen. in Anglesey, in Charles ye 1sts time. Some Parts of it copied then, out of Wrn. Penllyn's Book."

The MS. up to f. 10 (including the above) is in a later hand, apparently written about 1783, which date occurs in it. At f. 10 the old music begins, the writing is about the early part of the 17th cent. The music is in tablature—the words are Welsh. At fol. 58 is (apparently) a draft of a letter in English, dated 1648. At fol. 59 the later hand begins again, with extracts from Welsh works, and MSS. relating to Welsh Music. The whole MS. contains 64 ff.

The portion containing the Ancient Music is printed in vol. iii. of the 'Myvyrian Archaeology of Wales' (1807). See Transactions Cymmrodorion Soc. i. 361.

Other collections of Welsh music in the Museum are, Ad. MS. 14,939, 'Collections by R. Morris, 1779.' Do. 15,021, Account of the Old Welsh Notation. Do. 15,036, Tracts on ancient Welsh Music transcribed by Hugh Maurice for O. Jones, from a MS. by John Jones.[ J. T. ]

- ↑ See vol. iii. p. 648–650.

- ↑ Many alterations have recently crept into the ordinary versions of this tune; but the above is the form in which it is given by Edward Jones in his 'Relicks of the Welsh Bards,' 1791.

- ↑ Dr. Rhys's Grammar makes mention of a Bard named Gruffydd Ben Rhaw; and probably this tune was composed about the beginning of the 15th century, or at least acquired this title at that time. Edward Jones' Relics of the Welsh Bards, p. 165.

- ↑ The prose contained in the MS. is to be found in Dr. John David Rhys's Welsh and Latin Grammar of 1592.

- ↑ Not to be confounded with the 'Musurgia' of Kircher. [See vol. ii. p. 438.] Othmar Luscinius was a learned Benedictine monk, and native of Strassburg. His work is in two parts; the first containing a description of the Musical Instruments in his time, and the other the rudiments of the science. To these are added two commentaries, containing the precepts of polyphonic music.