A short guide to Syria

A SHORT GUIDE TO

SYRIA

WAR AND NAVY DEPARTMENTS

Washington, D.C.

For use of Military Personnel only. Not to

be republished, in whole or in part, without

the consent of the War Department.

Prepared by

SPECIAL SERVICE DIVISION, SERVICES OF SUPPLY

UNITED STATES ARMY

A SHORT GUIDE TO

SYRIA

WAR AND NAVY DEPARTMENTS

Washington, D. C.

A SHORT GUIDE TO SYRIA

| CONTENTS | ||

| Page | ||

| Introduction | 5 | |

| Ancient Land—Holy Land | 8 | |

| The Syrians | 12 | |

| The Arabic Language | 14 | |

| Getting Along With the Syrians | 15 | |

| Climate and Sanitary Conditions | 29 | |

| Currency, Weights, and Measures | 35 | |

| Some Important Do's and Don'ts | 37 | |

| Hints on Pronouncing Arabic | 41 | |

| Useful Words and Phrases | 45 | |

| A Glossary | 50 | |

"If you give, give plenty; and

If you strike, strike hard."

Syrian Proverb

YOUR UNIT has been ordered to Syria. Soon you will be standing on the shores of a sea or on a desert which has played a great part in world history.

You, an American soldier, are now one of the countless fighting men, over the past two thousand years, who have tramped across this neck of land connecting Europe and Asia. Alexander the Great, Caesar, Napoleon—all have struggled on this land for world dominion.

Here two great religions—Christianity and Judaism—sprang up. Egyptian, Babylonian, Persian, Roman, Turkish and European civilizations have left a mark on Syria's sparsely inhabited lands. And for three centuries, waves of Crusaders from Europe fought the Saracens for possession of this Holy Land.

You are in Syria to fight—and to win—against Hitler, who seeks world domination. And a big part of your job is to make friends for your cause—because this is a war of ideas, just as much as of tanks, planes and guns.

You're here to prevent Hitler from taking over this strategic land. He's tried once and probably will again. That's why the Free French and the British occupied Syria in July 1941.

Under the League of Nations, France was given a mandate over Syria after World War I. When France surrendered in World War II, German "tourists" began to filter into the desert. Then the British and Free French acted to protect the oil fields and pipe lines and guard this "land bridge" to Asia.

Your coming will be welcome to Syrians. In fact, at the end of the last war, Syria sought to be placed under American mandate protection. And, too, many Syrians have been educated at the American University at Beirut. So, you are in a friendly country and you won't have much trouble making friends, if you use ordinary horse sense in your dealings with the people of this land. But, with the best intentions in the world, you're likely to make serious mistakes, if you don't learn a little something about Syrians and their ways of doing things. This pamphlet will help to give you a quick picture of Syria which may make it easier to get along.

This is a War Of Ideas. One of the ways to beat the Axis in Syria, and in other parts of the Moslem world, is to convince the people that the United Nations are their friends. From the outbreak of this war, Axis nations have tried, through their propaganda machines, to kindle a religious war of Moslems against Christians. They hoped to spread a fire of hate from Turkey and Arabia all the way across the North African coast. Their plans have failed because the Moslems, deeply religious, know that the Nazi return to heathenism is a threat to their religion, as well as to others.

By showing your understanding of Moslem character and custom, by your own conduct in your relations with the Syrian people, you can maintain the good reputation that Americans already enjoy. And you can, in a very effective way, take the poison out of Nazi propaganda.

ANCIENT LAND—HOLY LAND

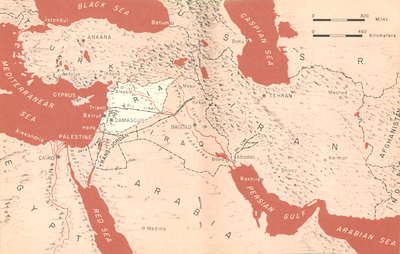

WHEN you stand on the shores of Syria, with your back to the Mediterranean, you will be looking eastward across the great "land bridge" between Europe and Asia. Across it, for centuries, came caravans carrying silks, spices, and the jewels of the Orient to the western world.

We're a bit spoiled now. In about 12 hours a ship may go through the 100-mile ditch in the sand, the Suez Canal, and start on through the Red Sea to India. And that ditch was opened only in November 1869, after nearly 10 years of hard work by the French engineer, deLesseps.

Before then, and since the days of the Phoenicians, the long, dangerous, costly route was from Syria, through Iraq down the Persian Gulf to India. Then Sidon was the great Eastern Mediterranean port from which the Phoenician traders sailed to the Atlantic and even to Britain. Today, Sidon and its sister city Tyre are only small ports on the Levant Coast. In their place is Beirut (bay-root) the leading Syrian port, followed by Tripoli and Latakia (lat-tah-kee-ya).

The Coastal Cities. In these thriving cities, you'll see a few principal avenues, thronged with every kind of people of the Near East—merchants and fishermen, boatmen and camel drivers, talking several different languages.

The people you'll meet are shrewd and well-informed as most trading peoples are, with a variety of manners and customs, picked up here and there.

Beirut is a particularly cosmopolitan city, the seat of American University, an American Christian school that has had considerable influence in the spread of education throughout Syria.

Latakia, despite its shops, hotels, movies, restaurants, and bathing beaches, is still a typical Syrian town. Its tiny stores are like cubby-holes in a wall and they offer their goods in flat platter-like baskets which are piled high with oranges, olives, or dates. Latakia is famous in America because it gives to us some of the finest tobacco in the world, used to flavor American brands.

The Oldest City in the World. Back of the Lebanon Mountains, to the east, is a wide valley, and back of that the Anti-Lebanon range, marking the end of the fertile coastal section and the beginning of the desert. But here, like a "green island" in the desert, is Damascus, reputed to be the oldest city in the world, dating back to more than 2,000 years before Christ. Called the "Pearl of the Desert," it is a beautiful city, with thousands of white houses, great orchards and gardens, high-domed mosques, and palaces and bazaars, thronged with a motley crowd of Armenians, Greeks, and Arabs, and donkeys, camels, goats, and sheep.

Sweetmeat sellers and auctioneers fill the thoroughfares with their noise and stir; eating shops are bedlam and the bazaars crowded. There the dukkans (duk-KAAN) (stores) are piled to the ceiling with calicos, muslins, and silks. On small, 10-foot platforms, in front of each dukkan sit the merchants, cross-legged. Coffee sellers pass up and down, offering their wares. Merchants furnish their customers with cigarettes and coffee free, and gossip is always going—on crops or politics or what not.

The great meeting place for the Moslems in Damascus is the famous Mosque—once a heathen temple, then a Christian church, and later held jointly by Moslem and Christian. Since the 8th Century A. D., it has been Moslem, but still contains the shrine of John the Baptist, revered alike by Christian and Moslem peoples. It is one of the most magnificent structures in the world. Costly rugs cover its vast stone floor and its roof is supported by marble pillars.

THE SYRIANS

You'll see a lot of the cities and their people, but it's the desert and the desert folk that give flavor to the land.

THE desert Arab, or tribesman, has few necessities beyond coffee, sugar, and tobacco. Even on feast days he eats astonishingly little, and when no guest is present, bread and a bowl of camel's milk is about all he requires—and he can make long marches on that simple fare. It is said that the Bedouin (bed-win) is never without hunger. But when a notable guest is in camp, a sheep must be killed and a bountiful meal of mutton, curds, and flaps of bread is the order of the day.

More than 250,000 Bedouins roam the desert fringes in Syria with their herds of camels and huge flocks of sheep searching for pasture. You'll be able to recognize the Bedouin by his flowing robes, his long head scarf and, frequently, by his long side curls.

Desert Farmers. Less romantic perhaps than the Bedouin or the warlike Jebel Druze (je-bel drooz) are the farmers, but they form the bulk of the 3½ millions of people of Syria-Lebanon. They do a remarkably efficient job in getting what they do out of it. The average farmer just manages to sustain his family, and has little left over. Rural incomes in Syria average about $80 a year, debts are always large and mortgages heavy.

Mostly the farmers live in small, compact villages built around springs or near other sources of water. To you, their methods may seem primitive, but at least one American conservation expert has said that their method of terracing fields is one of the finest examples of soil conservation in the world. And their wooden plow is well suited to the shallow, stony soil they have to work.

A large proportion of these desert farmers are share-croppers or tenants, the land they till being held by land lords who sometimes control several or more villages and vast acres of cultivable land.

Translation—There is no conqueror but god

THE ARABIC LANGUAGE

SOME Syrians speak English, or at least a little English, but the native language is Arabic and you will need to know a little of it to get along well.

The Arabic language is spoken by millions of people living throughout the coast of North Africa and the Near Eastern countries. There are, of course, differences between countries in these regions both in the use of certain words and in the way they are pronounced. But these differences are easy to understand and to learn. You won't be able to read Arabic signs or books because they use a different alphabet from ours.

You won't have to learn many words since in everyday Arabic a few simple words and phrases go a long way. The majority of Syrians themselves use perhaps only a few hundred words—and they get along pretty well on that.

At the end of this guide, you'll find a list of words and phrases and some idea of how to pronounce them. Even if your pronunciation isn't too good, it will please the Syrians to have you even attempt to talk to them in their own tongue. And they'll like it especially if you use their polite salutations—they are very polite themselves.

GETTING ALONG WITH THE SYRIANS

THE Syrian people are friendly to us now. If Hitler's agents should turn them against us, the consequences might be very serious. They are the people who can supply water if they like you or poison the wells if they don't. They can guide us through mountains and desert, or lead us astray. They can tell us what the Germans are doing when they like us, or tell the Germans what we are doing if they don't like us. If they like us, they can get rid of the German agents among their tribes. If they dislike us, the Germans might arm them and give us a lot of grief.

Maybe you understand now why it is so important for you to learn how to get along with the Syrians and keep them our friends.

You can do this chiefly by understanding their customs, by treating them politely, and by being careful never to offend them through carelessness or ignorance.

Courtesy. The Syrians make a good deal of courtesy and politeness. If a man should kiss your hand or raise his fingers to his lips after shaking hands with you, don't laugh. It is his way of paying you a compliment.

Americans slap each other on the back and jostle each other in fun. Syrians do not. Avoid handling them and do not try to wrestle with them. Even if you think you know them well, do not touch their bodies in any way. Above all, never strike a Syrian. They do not know how to box. You might think you were just sparring and knock a man down or even injure him. They would be certain to misunderstand it and word would spread rapidly, as it does among people who don't read and who rely on gossip for information, that Americans hit people on the jaw. Besides, it is dangerous. Syrians, like most people of this desert world, know how to use knives. Never get angry at these people. It is one thing to issue orders and get them carried out; it is another to rub the people the wrong way. Save your fighting for the enemy. You're here to fight with these people against the Axis.

Manners, Private. Syrians, like most orientals, pay much attention to good manners. Moslems do not let other people see them naked. Do not urinate in their presence. They do this squatting and dislike to see others do it standing up. These things may seem trivial, but they are important.

Manners, Public. You will find it difficult sometimes to distinguish manners from religious practices. Many Syrian customs are religious in their origin. Moslems live their religion far more intensely than most of us do. Begin by watching them carefully.

Social customs enter into not only your personal relations with Syrians you have met, but all public activities, such as buying in the bazaars, eating and drinking in public places, and the relations to women. Learn the forms of address on meeting people and use them.

Understand that bargaining when making a purchase is customary. It is part of the social life of these people. They do not trade just for the money, but to meet with people, learn their ways, practice their own skills and

judgments. To bargain intelligently is to show understanding in values. They may treble the price they expect you to pay. If you pay it, they know you don't know the real values. But bargain politely. Most of these tradesmen know each other well and treat one another as host and guest. Friendships result from trade. In the larger "westernized" shops, there is usually a fixed price. So, you won't have to haggle with them.

Hospitality. The result of such contacts may yield you hospitality and friendship. It is customary for tradesmen to offer customers coffee and cigarettes. Do not refuse. Don't leave your coffee half drunk. Should you be offered a second and even a third, take it. But it is considered bad form to accept a fourth cup. If you take a fourth, or refuse a second or a third, your host will put you down as wanting in manners. This may seem absurd to you. So what? Your customs seem just as absurd to him. When in Rome, do as the Romans do, as the saying has been for thousands of years.

A few things to remember about Moslem Syrians is that they do not eat pork and they do not drink liquor. This is a religious matter. Don't ask why. Respect it. You'll see something about this religious question later. As a social matter, politeness demands that you accept these things without question. So do not drink liquor in their presence. It offends them, especially, to see anyone drunk. Even as a joke, don't offer or urge them to drink liquor or eat pork.

A few rules are essential. Never touch the food until your host has said grace ("Bismillah") and then not till he has told you to. Eat only with your right hand—it is considered very rude to use the left, even if you are a southpaw. Do not cut native bread with a knife. Break it with your fingers. A servant will come along with basins and water for all to wash their hands after dinner.

Women. You will not find Moslem women in the company. Ladies generally remain hidden. It depends largely on who your host is, of course. But among Moslems, particularly, women do not mingle freely with men. The greater part of their time they spend at home and in the company of their own families. It is considered a very serious breach of manners to even inquire about the women. So even if you are invited to a home, you will not see much of the women.

In public, many Moslem women go veiled. If a woman has occasion to lift her veil while shopping, do not stare at her. Look the other way. Do not loiter near them when at the bazaars. Do not try to photograph them. It will cause trouble.

Never make advances to Syrian women or try to get their attention on the streets or other public places. The desert or village women may seem to have more freedom, but they do not. Any advances on your part are sure to mean trouble, and plenty of it. Syrians will immediately dislike you if you do not treat their women according to their standards and customs.

These rules are important. Don't make a pass at any woman. It will cause trouble. And anyway, it won't get

you anywhere. Prostitutes do not walk the streets, but have special quarters.

Religion. Questions regarding religion are as distasteful to Syrian Moslems as are questions regarding women. It is well to avoid any kind of religious discussion or argument.

Two-thirds of the Syrians are Moslems, and the remaining third are Christian. The Moslem community is more or less set off by itself and recognized by its veiled women, the sombre, dignified aspect of the men and by their mosques. The distribution of Moslems and Christians is roughly according to the boundaries of Syria and Lebanon. Lebanon is mostly Christian, while Syria is mostly Moslem.

Both the Moslem and Christian groups are broken up into subdivisions or sects. One of the more important Moslem sects are the Druze. The Druze live in a semi-desert section in the south part of Syria called Jebel Druze. They keep very much to themselves, are a proud and reserved people, and are noted for their daring and bravery in warfare.

The Moslems follow the religion founded by Mohammed. Do not call it the Mohammedan religion, for they do not worship Mohammed as Christians worship Christ. Mohammed is not God. Allah is God, and

Mohammed only His prophet. The religion is called Islam and the people who follow it are called Moslems. There are five fundamental principles of Islam:

- 1. One God, and Mohammed the PROPHET.

- 2. Prayer five times a day.

- 3. Giving of alms.

- 4. Fast of Ramadan.

- 5. Pilgrimage to Mecca.

Moslems pray five times a day no matter where they are at the moment of prayer. They bow in the direction of Mecca in Arabia, the holy city of the Moslems. At the mosque (mosk) they bow in prayer which consists of reciting passages from the Koran, which is their Bible. Giving of alms is a religious practice.

All true Moslems observe a month of fasting called Ramadan. This period is similar to our Lent. In 1942, Ramadan begins September 12. In 1943, it will be about 2 weeks earlier. During this period the Moslems do not eat, drink, or smoke between sunrise and sunset. Do not offer them food, or ask them to drink or smoke except after dark. Respect all hesitations or refusals without persuasion. Any drawing of blood at this time is to be avoided. Even an accidental scratch or nosebleed inflicted on a Moslem by an unbeliever may have serious consequences. Remember that the Moslems' tempers are short during the strains of this month. They cannot be expected to work efficiently. So go easy on them. Respect the observance of their holiday.

Steer clear of mosques. Never smoke or spit near a mosque. To repeat a warning—avoid any kind of religious discussion or argument. After all, we are fighting this war to preserve the principle of "live and let live."

Mecca. The fifth important ritual of Moslem religion is the pilgrimage to Mecca. So vital is this to Moslems that the railroad from Damascus to Mecca, in Arabia, started in 1901 and completed in 1909, was built entirely from subscriptions by the faithful from all over Islam to make easier the pilgrimage to the holy city. No "unbeliever" is ever permitted to enter Mecca.

How to Get Along in the Villages. On entering a village or farming district, there are definite rules of procedure in regard to introductions. No matter how small the detachment, the leader should find out whether or not the area is controlled by a landlord, called a "malik il-ard" (maa-lik il-ard). If so, he should call on the landlord and seek his cooperation and friendliness. If the area is controlled by an absentee landlord, find out who is his representative, or "wakeel" (wa-keel) and make yourself known to him.

Every village, whether or not it is controlled by a landlord, has its mayor, who is called the "mukhtar" (mukh-tahr). On entering a village, the leader should introduce himself to the mayor and call at his house. If he cannot find the mayor, he should make himself known to the eldest man in the village, or to the priest in a Christian village, or the "imam" (i-maam) or "sheikh" (shaykh) in a Moslem village.

You can usually tell a Christian village from a Moslem village by the simple method of observing whether the village possesses a church or a mosque. A mosque always has a minaret or tower from which prayers are called.

If you find both a mosque and a church in a village, you will know that the community is composed of both Christians and Moslems. In all probability, each group has its own section of the village. If you find yourself in one of these communities, be careful not to favor one group more that the other. If you buy goods, for instance, be sure to patronize both groups. Treat the priest and sheikh with equal respect.

The friendliness and cooperation you will get depend largely on your dealings with the influential citizens who have been mentioned—the landlord, bailiff, mayor, sheikh, or priest. They are the persons with the most authority and are the respected members of the community. All transactions regarding supplies, quarters, etc., should be carried on through them. To disregard these local leaders would be considered a serious breach of Syrian etiquette and would incur the ill will of the whole community. So treat the local leaders with respect at all times and entertain them whenever possible. Another helpful person is the village watchman, the "natour" (naa-toor). The watchmen are usually well informed on the local geography and gossip. They are often the first to know of unusual happenings and can thus be very useful to you. But remember that it is the watchman's business to be suspicious of strangers. Therefore you must win his trust before he is willing to help you. A suspicious watchman will often give you false information purposely. This also holds true of the local leaders if they mistrust you. At all times it is to your advantage to make friends! Here are a few things to remember in winning the friendship of the villagers:

Respect village property. Keep to paths and roadways. Do not enter cultivated fields or take fruits and vegetables from orchards and gardens. Villagers depend on these crops for their living. Their margin of reserve is very slim. Do not gather fuel without permission. It also is limited. Each and every tree has its owner and wood-lots are sometimes the property of the village. Sometimes the groves are considered holy and no person may touch the wood. It is even considered improper to sit under the shade of a tree. The Syrians themselves mostly use dried animal dung for fuel. Learn to use this.

How To Get Along in the Desert. If you are in the desert, remember that every bit of land is the property of some specific group of tribesmen. The leader of your unit should discover to what tribe or group the land belongs

and seek out and pay a call on the sheikh or headman. Always try to obtain permission before taking water from desert wells. The Syrians have complicated water rights. Never be wasteful of water. It is their most valuable possession. It is likely to be yours, too.

The tribesmen admire courage and resourcefulness. Let them see that you have these qualities. They will be grateful of any generosity you can show them, such as a lift along the road. Whenever possible, give the men and children empty tins or other items you can part with. A discarded gasoline can, for example, is considered a proud possession.

"Rain is a

Mercy from God"

—Arab proverb

CLIMATE AND SANITARY CONDITIONS

THE climate of the coastal portion of Syria is a good deal like that of Southern California. The winters are cool, but not cold, with some rain, while the summers are warm and sunny. Orange and olive groves abound. Back of the coastal plains stand the forested Lebanon Mountains (remember the cedars of Lebanon in the Bible?) which are covered with snow in the winter. Skiing is a new and popular sport here.

In the valley or "central depression" between the Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon mountains, the climate is somewhat drier than the coast, and irrigation is often necessary. The winters are colder and the summers warmer. This valley, however, is fertile and well cultivated. Wheat and other cereals are its principal crops.

Unlike the forested Lebanons, the Anti-Lebanon range is bleak and barren, without much rainfall. It is a fitting approach to the desert, which stretches eastward from its foothills. Though this desert occupies by far the greater portion of Syria, it is only sparsely inhabited in comparison with the rest of the country, because of its unfriendly and unfertile character. Yet the Syrian desert is not like the great Sahara desert in Africa, all sand and wasteland, but more like the deserts of the southwestern United States—a stony soil covered with light vegetation, and with waterholes at fairly frequent intervals.

In a strategic way, the desert is perhaps the most important part of Syria to the United Nations, because across it run the great pipelines from the oil fields of Iraq to the Mediterranean, and also because of its position as the gateway to Persia and India beyond.

Sanitary Conditions. In general, Syria is a healthful country. It even hopes some day to become known as the health resort of the Mediterranean. Still, sanitary conditions in many parts of the country are not like those we are accustomed to, and certain precautions must not be neglected. A little knowledge may help to avoid serious illness.

Keep your hat on when you are in the summer sun in Syria, In this kind of a climate it is very easy to let yourself be burned and think nothing of it. But next day you are likely to wake up with black blisters and possibly fever and delirium. It is not necessary to wear a sun helmet; a service hat is usually sufficient. But whatever

you wear, be sure that it shades the back of your neck as well as the top of your head. If you expose the back of your neck you are inviting sunstroke. Protect your eyes too.

In the desert, be prepared for extremes of temperature. The days are very hot. The nights can be very cold.

Boil your drinking water or see that it is properly chlorinated. There is adequate pure water in the cities of Beirut and Damascus (though not the open river water in the latter city, which is impure).

Avoid eating unwashed lettuce and other raw unwashed vegetables. They may be contaminated by human excrement. Outside the cities, little progress has been made in sanitation. Wash raw fruits or peel them before eating them, because the skins may have become contaminated by flies or by human contact. Keep all food away from flies.

If you keep to these rules you will have a good chance of avoiding typhoid, paratyphoid, and dysentery—all common diseases in Syria. If you do get dysentery or diarrhea, cut your diet and include plenty of "leben" (le-ben). Leben is a sour milk product and is one of the most healthful dishes of the country. It can be mixed with water and drunk as a cooling drink. You will find it easy to obtain and it will relieve dysentery.

Malaria is quite prevalent in Syria. It is carried by a particular kind of mosquito which breeds in marshy areas, uncovered wells and cisterns, and in shallow water pools along the seacoast. If at all possible, stay away from areas where malaria is common. When you can't do this, sleep under nets and keep your arms and legs covered, especially at dusk.

Sandflies, which are smaller than mosquitoes and which can get through an ordinary mosquito net carry a slight three-day fever which is not serious but is weakening. It is known as sandfly fever. Sandflies are most prevalent in midsummer. Coating yourself with a light oil will give you some protection from them.

Venereal disease is fairly widespread in Syria. Don't take chances.

These are some general health suggestions. Your medical and sanitary officers will give you others.

CURRENCY, WEIGHTS, MEASURES, ETC.

Syrian Currency. The rate of exchange of Syrian money to United States currency varies, so that the table below can only give approximate ratios. The principal unit of currency is the Syrian pound, which is worth 46c in American money and is divided into 100 "piastres" (pee-AS-turz) or "irsh" (the Arabic word for piastre). The approximate values of the various piastre pieces are given below. An easy way to remember Syrian currency is to think of each piastre as being worth just about half of an American cent.

| 1 pound (100 piastres)=46c U. S. 50 piastres=23c U. S. 25 piastres=11c U. S. 10 piastres=5c U. S. |

5 piastres (called "1 franc")=4c U. S. 1 piastre=½c U. S. ½ piastre=½c U. S. |

Palestinian Currency. In some parts of the country you will also run into Palestinian currency, so you had better know something about its value, too. The principal unit of Palestinian currency is the Palestinian pound, which is worth approximately $4,00 in American money and is divided into 1,000 "mils." Like the Syrian piastre, each mil is worth about half of an American cent. The table below will give you the approximate rates of exchange of the various mil pieces.

| 1 pound (1,000 mils)=$4.00 U. S. 100 mils=40c U. S 50 mils = 20c U. S. 20 mils=8c U. S. |

10 mils=4c U. S. 5 mils=2c U. S. 2 mils=0.8c U. S. 1 mil=½c U. S. |

The Moslem Calendar. The official calendar of Syria is the same as ours. It is used for all business transactions. But the Moslems reckon time by a lunar (moon) calendar. So a given date in the Moslem calendar will vary from one year to the next on our calendar. The lunar calendar is of no importance to us except in telling the time when Ramadan will occur. Ramadan is the Moslem Lent, about which you have read earlier in this guide.

Weights and Measures. The metric system is used for all official measurements of distance and area in Syria. The unit of length in the metric system is the "meter" (meet-ur), which is 39.37 inches, or a little more than our yard. The unit of road distances is the "kilometer" (kill-oh-meet-ur), which is 1,000 meters or 5/8 (a little over a half) of one of our miles.

The unit of square measure is the "hectare" (heck-tair), which consists of 10,000 square meters or about 2½ of our acres. A local square measure is the "dunum" (du-num), which is equal to 1,000 square meters or about 1/4 of an American acre.

The unit of weight in the metric system is the "kilogram" (kill-oh-gram), which equals 2.2 pounds in our system. A local measure is the "rotl" (ruhtl). This unit varies from one locality to another. It ranges from about 5½ to 6½ pounds.

Liquids in the metric system are usually measured by the "liter" (lee-tur). A liter is a little more than one of our liquid quarts.

SOME IMPORTANT DO'S AND DON'TS

Don't enter mosques.

Never smoke or spit in front of a mosque.

If you come near a mosque, keep moving and don't loiter.

Keep silent when Moslems are praying and don't stare.

Discuss something else — never religion or women — with Moslems.

Avoid offering opinions on internal politics.

Shake hands with Syrians; otherwise don't touch them or slap them on the back.

Remember that the Syrians are a very modest people and avoid any exposure of the body in their presence.

Start eating only after your host has begun.

Eat with your right hand—never with your left, even if you are a southpaw.

Always break bread with your fingers—never cut it.

Bread to the Moslems is holy. Don't throw scraps of it about or let it fall on the ground.

Leave some food in the bowl—what you leave goes to the women and children.

Eat only part of the first course—there may be four or five more coming.

Don't give Moslems food containing pork, bacon or lard, or cooked in pork products.

Don't eat pork or pork products in front of Moslems. Be pleasant if Moslems refuse to eat meat which you offer. They may consider it religiously unclean.

Don't give Moslems alcoholic drinks.

Drink liquor somewhere else—never in the presence of Moslems.

Knock before entering a house. If a woman answers, wait until she has had time to retire.

Follow the rule of your host. If he takes off his shoes on entering the house, do the same.

If you are required to sit on the floor in a Syrian house or tent, cross your legs while doing so.

When visiting, don't overstay your welcome. The third glass of tea or coffee is the signal to leave unless you are quartered there.

Don't bring a dog into the house.

Be kind to beggars. They are mostly honest unfortunates. Give them some small change occasionally.

When you see grown men walking hand in hand, ignore it. They are not "queer."

Be kind and considerate to servants. The Syrians are a very democratic people.

Avoid any expression of race prejudice.

Talk Arabic if you can to the people. No matter how badly you do it, they like it.

Shake hands on meeting and leaving.

On meeting a Syrian, be sure to inquire after his health.

If you wish to give someone a present, make it sweets or cigarettes.

If you are stationed in the country, it is a good idea to take sweets and cigarettes with you when you visit a Syrian's house.

Show respect toward all older persons. If serving food, the oldest person should be served first.

Be polite. Good manners are essential among the Syrians. Be hospitable to Syrians whenever possible. Do not turn away callers. Serve them coffee or tea.

Bargain on prices. Don't let shopkeepers or merchants overcharge you; but be polite.

Be generous with your cigarettes.

Above all, use common sense on all occasions. And remember that every American soldier is an unofficial ambassador of good will.

HINTS ON PRONOUNCING ARABIC

THESE are pronunciation hints to help you in listening to the Arabic language records which have been supplied to your troop unit. They will also help you with the pronunciation of additional words and phrases given in the vocabulary below, which are not included in the records.

Arabic is spoken over a great area in North Africa and the Near East. There are some differences between regions, both in pronunciation and the use of words. The dialect and words you are going to hear on this set of records are Syrian and Palestinian and you will be understood in Syria and Palestine and in the cities of Trans-Jordania and in Cairo and the Egyptian Delta region. If you should go on to other regions, where other varieties of Arabic are spoken, you will be given further information at that time. Don't worry about that now.

There is nothing very difficult about Arabic—except that you won't be able to read Arabic signs and newspapers you will see. That is because they use a different alphabet from ours. Therefore, the instructions and vocabulary below are not based on the written Arabic language, but are a simplified system of representing the language as it sounds. This system contains letters for all the sounds you must make to be understood. It does not contain letters for some of the sounds you will hear, but it will give you enough to get by on, both listening and speaking.

Here are a few simple rules to help you:

1. Accents. You know what the accented syllable of a word is, of course. It is the syllable which is spoken louder than the other syllables in the same word. We will show accented (loud) syllables in capital letters and unaccented syllables in small letters.

2. Vowels. These are the kind of sounds we represent in English by a, e, i, o, u, ah, ay, ei, oi, etc. Just follow the key below and you will have no trouble.

| a or A | equals | the a in pat usually, but if the man you are talking to doesn't seem to get you at first, try sounding it like the o in pot; sometimes it is pronounced that way. There is no fixed rule. You'll just have to listen and learn. (Example: tif-HAM-ni meaning "do you understand me.") |

| AA | equals | the a in demand—but stretch (lengthen) it. (Example: WAA-hid meaning "one.") |

| AH | equals | the a in father—but stretch it. (Example: NAH-'am meaning "yes.") |

| AI | equals | the ai in aisle—but stretch it. (Example: AI-wa meaning "yes." |

| AY | equals | the ay in day—but stretch it. (Example: WAYN meaning "where.") |

| AU | equals | the ow in now. (Example: AU-wal meaning "first.") |

| e or E | equals | the e in pet. (Example: WE-led meaning "boy.") |

| EE | equals | the ee in feet—but stretch it. (Example: ya-SEE-di meaning "sir.") |

| i or I | equals | the i in pit. (Example: ya-SIT meaning "madam.") |

| O | equals | the o in go—but stretch it. (Example: fa-SOL-ya meaning "beans.") |

| OO | equals | the oo in boot—but stretch it. (Example: SHOO IS-mak meaning "what is your name.") |

| u or U | equals | the u in put. (Example: u'-ZUR-ni meaning "excuse me.") |

| uh or UH | equals | the u in but. (Example: min-FUHD-lak meaning "please.") |

3. Consonants. The consonants are all the sounds that are not vowels. Pronounce them just as you know them in English. All consonants should be pronounced. Never "slight" them. Here are some special consonant sounds to learn:

| h | small h is always pronounced with the h sound except after small u. Listen carefully to the h sound on the records. |

| kh | is pronounced as when clearing your throat when you have to spit. Listen carefully for it on the records. |

| gh | is pronounced like kh except you put "voice" into it. It is like the sound you make when you gargle. Listen carefully to this sound on the records. |

| sh | is like the sh in show. |

| (') | is to be pronounced like a slight cough. listen carefully for it on the records. Whenever it is indicated, pronounce it clearly, but do not pronounce it even accidentally where it is not indicated, or you will be misunderstood. |

| s | is always pronounced like the s in hiss. |

Translation—HELP IS FROM GOD AND VICTORY IS NEAR

LIST OF MOST USEFUL WORDS AND PHRASES

HERE is a list of the most useful words and phrases you will need in Arabic. You should learn these by heart. They are the words and phrases included on the Arabic language records, and appear here in the order they occur on the records.

Greetings and General Phrases

English—Simplified Arabic Spelling

Good day—na-HAA-rak sa-'EED

Good evening—MA-sal KHAYR

Sir—ya SEE-di

Madam—ya SIT

Miss—AA-ni-sa

Please (to a man)—min-FUHD-lak

Please (to a woman)—min-FUHD-lik

Please (to more than one person)—min-FUHD-il-kum

Excuse me (to a man)—u'-ZUR-ni

Excuse me (to a woman) —u'-zur-EE-ni

Excuse me (to more than one person)—u'-zur-OO-ni

Thank you (to a man)—KAT-tar KHAYR-ak

Thank you (to a woman)—KAT-tar KHAYR-ik

Thank you (to more than one person)—KAT-tar KHAYR-kum

Yes—NAH-'am

No—LAA'

Do you understand me—tif-HAM-ni

I don't understand—A-na mish FAA-him

Please speak slowly—min FUHD-lak, Ih-ki SHWAI SHWAI

Turn r i g h l— DOOR lil-ya MEEN Turn left— DOOR lish-MAAL Lo cation Where is WAYN 'I 1C railroad station — WAYN a restaurant— WAYN H- ii-ma-HAT-ta UAT-'em a toilet— WAYN BAYT 3- a hotel— WAYN il-O-TAYL MAI Direction! Straight ahead — DUGH-ri Please point — min FUHD-lak. far-ZHEE-ni Distances are given in kilometers, not miles. One kilometer equals % of a mile. Kilometers — ^ee-h-imt-RAAT Numbers One — WAA-hid Vaw—AR-ia-'a Two— it-NAYN Five— KHAM-si Three— TLAA-li But when you use the numbers with other words notice what happens: One kilometer — foe-lo-MI-tir Four kilometers — AR-ba' k.ee-lo- mit-RAAT Five kilometers — KHAMS k*e- WAA-hid For two kilometers you say "couple of kilometers" all in one word. Two kilometers — ^te-lo-mit- RAYN Three kilometers — TLAAT k™- h- nut -R A AT So -m it -R A AT Six— SIT-ti Seven—SAB-'a Eight— TMAA-m Nine— T/S-'a •Xcn—ASH-ra

But notice again: Six kilometers — SIT fye-h-mil- RAAT Seven kilometers — SA-bi' fyce- lo-mit-RAAT Eight kilometers — ta-MAAN fcee-to- mit-RA AT Nine kilometers — Tl-si' ^ee-lo- mit-RAAT Ten kilometers — 'A-shar t(re-lo- mil-RAAT From eleven on, the same form of the number you use in. counting is used with the simple form of the word as follows: Eleven kilometers — ih-DA'SH fee-lo-!f-)ir Twelve kilometers — it-NA 'SH fce-lo-MI-fir Thirteen kilometers — tlat-TA 'SH kee-io-Ml-tir Fourteen kilometers — ar-ba'- TA'SH k."-lo-m-tir Fifteen kilometers — liha-mii- TA'SH fye-lo-Ml-br Sixteen kilometers — sil-TA'SH kee-io-MI'tir Seventeen kilometers — sa-bi'- TA'SH ke'-to-Ml-tir Eighteen kilometers — tmen- TA'SH et-lo-Ml-tir Nineteen kilometers — ti-si'- TA'SH kee-lo-MI-tir Twenty kilometers— 'ish-REEN kee-lo-MI-tir For "twenty-one," "thirty- two," and so forth, you ado! the simple form of the numbers to the words for "twenty" and "thirty" just as we sometimes say "one and twenty," thus; Twenty-one kilometers — WAA- hid ti-'ish-REEN l(ec-lo-MI-tir Thirty kilometers — tfa-TEEN kee-to-Ml-tir Thirty-two kilometer s — it- NAYN u-tla-TEEN bc-lo- M!-/ir Forty kilometers — ar-ba-'EEN bee-h-Ml-tir Fifty kilometers— { ham- SEEN kjce-lo-Ml-tir One hundred kilometers— Ml-yi kec-lo-Ml-tir But for 200 you would say "couple of hundreds" all in the same word: Two hundred— MEE-T.AYN Two hundred kilometers— MEE- T.IYN l^cc-lo-MI-lii- For 250 you say "couple o£ hundreds and fifty":

kilometers— MEE-TAYN «■

tygm -SEEN ipe-h-Ml-tir For 255 you would say "cou- ple hundreds, five and fifty":

kilometers— MEE-TAYN w

lihanu n-kham-SEEN {er-h- Mi-rir But for 555 you would say "five hundred and five and fifty":

kilometers — khams M!-yi 11-

khamt u-kham-SEEN eeAo- W-tir 1 kilomcLers— rlf fae-lo-Ml- tir What is— SHOO, AYSH this — HAA-ia What's this— SHOO HAA-da or AYSH HAA-da I want— BID-di cigarettes— B/ZMt sa-GAA- yir to eat— BID-di 0-4"' Foods Bread — KJtV-biz FruH—FWAA-kf Watet-7-MAl t—BAYD Steak— STAYK Meat — LA-him Potatoes — ba-TAH'Ua Rice — ruz Beans (navy)— fa-SOL-ya Beans (horse)— FOOL Fish — S.i-mak Salad— S.I -la-ia Milk— ha-LEEB Beer— BEE-ra A glass of beer— KAAS BEE-ra A cup of coffee— fin-ZHAAN 'Ak-wi To find out how much things cost you say: How much— 'ad-DAYSH costs — bi-KAL-Uj this — HAA-da How much docs this cost — 'ad' DAYSH bi-KAL-lil HAA-da

Money Piaster — 'irsh Two piasters — 'ir-SHAYN More than 2 piasters- ROOSH Pound — LEE-ra Two pounds — UR-TAYN More than 2 pounds — LEE- RAAT Time What time is it— 'ad-DAYSH is-SAY-'a Quarter past five — KHAM-si u- RU-bi' Half past six — sit u-NUS Twenty past seven — SAB-'a ti- TULT Twenty of eight is said "seven and two thirds" or "eight ex- cept one third": Twenty of eight — SAB-'a ii-int- TAYN or TMAA-ni IL-la TULT Quarter of — IL-la RU-bi' Quarter of two — ii-NAYN IL- la RU-bi' Ten minutes to three — TLAA-ii IL-la 'ASH-ra At what tiine — Al-ya SAY-'a the movie — is-Sl-fia-ma starts — bi-TlB-da At what time dots the movie start— Al-ya SAY-a' bi-TlB- da is-SI -na-t>iu The train— h-TRAYN leave — bi-SAA-fir At what time does the train leave— Al-ya SAY-'a bi-SAA- /(V ii-TRAYN Today— ;/-mW Tom orro w — BUK-re Days of the Week Sunday— YOM ii-HAD Monday— YOM it-NAYN Tuesday— YOM it-TLAA-ta Wednesday— YUM il-AR-ba-'a Thursday— YOM il-tya-MEES Friday— YOM il-ZfWM-a Saturday— YOM it-SEBT Useful Phrase* What is your name (to a man) — SHOO IS-mal;. What is your name (to a woman)— 5//00 IS-mib, My name is — IS-mt Docs anyone here speak Eog- lish— FEE HA-da HON BYlh-lii in-GLEE-zi Goodbye (by person leaving) — bi-KHAHT-rak Goodbye (by person replying) — t?i a- 'ts-sa-LA A -mi GLOSSARY [English — Arabic] Surroundings- Natural Objects bank (of river) — shtlht spring (water -hole, etc.) — darkness— ZUL-mi 'A1N daytime (tight)— na-HAHR trie stars— in-ZHOOM (plural) J.^u—BAA-dia Nl-zliim (singulai I field— HA-'il, marsh (plain) stnam—ZHAD-wd fire— NAHR the sun— ir/i-i'HAUi - , . , . wind — HA-it-j torest (woods) — hiirsh . ,,-,, , „. dav — YOM ^s^ho-SHEESB day ^ Wmomw _ ud BUK . the ground — ard gully (ravine)— ZHO^ra ^ay before yesterdav— AV-mal hill— tel im-BAA-rih lake — BA-ha-ra evening — it A -a/ the moon — li-'A-mat month — SHA-bir mountain — ZHE-bel morni ng — SU-bib the ocean — il-BA-har night — LAYL rain — SHi-m week — ZHUM-'a river — NA-ksr year — Sf-ni snow — teizb jcsladay—im-BAA-rif) SO Months of the Year January— KAA-NOON TAA-ni August— AAS February— SUB, -1 HT September— AY-LOOL Msuch—AA-DAHR October— tish-REEN AV-wal Aptir—NEE-SAAN Uavemba—titA-REEN TAA-ni May— Al-YAHR December— KAA-NOON AU- June — ho-ZAY-RA/N ted July— TEM-M OOZ Relationships boy — WE-ted or SUHbi man— nizb-ZHAAL or ZA-la- brother — ahb or KliAl mi (slang) child — WE-led mother — im daughter— £i'n/ sister — ukht father — A -boo son — I -bin girl — bint woman — MA-ra Human Body arms— DRAA-'AYN head— S/fHS back— UA-her leg — SAA' eye — 'AIN mouth — turn finger— US-bo" nose— mtm-KHAHR hot— IZH-ir teeth— SNAAN hair— SHA-'ir toe — US-bo' IZH-ir hand — £ED House and Furniture bed — FER-s/ii room — O-i/a blanket— h-RAAM stairs — DA-razh chair — KUR-;i stove — (cooking place) — SO-ba door— BAAB uhh—TAHW-Ii drinking water — MAI-yh SHU- wall— HAYT

- water for washing — MAI HI-

house— BAYT GHUH-sil kitchen — MAT-ba^h window — slmb-BAAK Food and Drink- Tobacco butler — ZIB-di cabbage- — mai-FOOF cauliflower — 'ar-na-BEET 01 ZAH-ra cigars— SEE-GHAHR cucumbers — k.bi-Y. II Ik curded milk — LA-ban food — A-I{il (cooked food) ta- BEEKH grapes — 'I-nab lemons— LA~i MOOh melons — bat-1 EEKH oranges — imr-dti-'A. IX urange juice — 'a-SEER bttr-du- 'AAN pipe — gAal-YOU radishes — Fl-zhil sah—Ml-lii sugar — SUK-kat xen—SHAH-i txtoacco—dtity-KHAAK tomatoes — ban-DOO-re turnip* — hjt w inc -u-tiEED [iridic — /All -Sir ai —kt-XEE-sa city — mc-DEE-tia or BA'lad m osc| ue — ZHA A -mi' path (trail, puss)- ma M. IR post office— BOS-ta ■ oltct post- M. KH'fa> road — tft'REE* or dttrh Surroundings shop ( store ) — ifii/i-k. I . i. srrcer— SUA A -ri' l.mvit — SI- town — BAL-da village — 'AR-yi or DAY-'a wcl— BEER hotel— O-TAYL oi io-KAN-dt animal — hai-WAHN b'pd—'Bi-FOOR camel — -ZHA-mei chicken (hen)— ZHAA-zM cow — BA-'ti-yi; Aog—kelb ials donkey (burrow, MAHR goat — -IN-zi horsi — h-SAHN mouse — I'AHR mule — BA-ghil jackass

pig — ^ A/n -ZEER rabbit^AR-tiab rat— zhir-DON aia—diib-BAAN Rcas—ba-RAA-GHEET mosquitoes — NAA-MOOS sheep— GHA -Rem snake — H.-ll-yi scorpion — 'A'-rab Insects lice — -'A-mal spicier — 'an-f(a-B00T bedbugs — bat Trade* and Occupations baker— Ifhal'-BAAZ zook—'ASH-thi barber — kal-LAA' farmer — fel-LAAh blacksmith— had -DA AD shoemaker — kun-D. >R-zhi buidKt—lah-HAAM tailor— ifcAaf-YyfHT Numbers first— AL'-u d ninth— TAAsi' second — f.-IA-ni tenth — 'AA-shir third — TAA-lit eleventh — UAA-di 'A -shut fourth — RAH-bi' tmdith—TAA-ni 'A-shar G f th— fCHAA -mis six t y—si't-TEEN sixth — SAA-dis seventy — sa-ha-'EEN seventh — SAA-bi' eighty — ta-ma-NEEN eighth — TAA-min ninety — aV- 7.7- V Clothing belt — zun-NAHR or KA-mar boots — ZHEZ-mi coat — SAH-kjo gloves— KFOOF hat — bur-NAY-ta necktie — gra-l'AAT or RAB-ta Mn—'a-MEES shoes — sa-RAH-mt sucks — al-SAAT sw< atct—ZHER'zi trousers— Aarr-ftf-LOA undershirt — 'a-MEES lah-TAA- tii Adjectives good— TAI-yib or KWAI-yis or im-LEEH bad— bai-TAHL big— kr-BEER small— ifl-GHEEK eh—SHMAAL or ya-SAHR iXtk—raa-REED or 'ai-YAAN •unA—TAl-yib or mab-SOOT hungry—ZHO-'AAN thirsty — 'a/-SH AA' black — AS-wai wh ite — UHB -yuhd red- — Ah-tnar blue — /fZ-ra' green- — ,/A'W -oV yellow— C/HS-/ar high— VH-/( low — WAH-A deep — gfot-MEE* shallow — jnj'/A gha-MEE' (not dtV]<) colli — BAA-rid (thing) or iar- DA AN (person) hoi — SHOB (weather) SV-kf»<» (thing) SHO-BAAN (person) wet — m lib-LOQL dry — NAA-thij X pensive- — GHAA-h c h cap—ir-KHEES empiy—FAH-di or FAA-ngls iu—mal-YAAN Pronouns, etc.

— /f-na

wc — lli-na you — in) (masc); IN-ti (fcni.); IN-tit (pi.) he— HOO she— K££ they — A Jim this— HAA-da these — ha-DOL that — /ia-DAAK those — ba-DO-LEEK who— MEEJV what-ri'HOO or .-n'5H how many — V'" how hr^id-DAYSH BYlB-'ad or ad-DAYSR tt-ma-SAA-ji i-h anyone — HA-da everybody — /(nl WAA-hU

i of — ni in -SHA AN from — min in — £E£ of — JMf'n above — FO' again — kjt-MAAN MAR-ra behind— WA-ra beside — zhemb below— ta hi hr—ba-'EED here— HON in front — 'ud-DAAM less — a-'AL Pre positions on — 'A -lii tu — W or li- up xo—ti-HAD with — njtf' or 6j- AcVerbs near — zhemb (adv.) or a-REEB (adj.) on thar side — 'AAa zhemb ha- DAAK on this side — 'A -la zhemb HAA- da there— hu-NAAK very — i/(-TEEk where— WAYN or FAYN more — AK-iar or ka-MAAN Conjunct lulls and — tea or »- but — LAA-kin if— Ma or 7-ZH or LAU m—AV or B-7L-/J that — in Phrases for Every Day How do you say ... til Arabic? KEEF bit-'OOL ... bit -A-ra- u What date is today? — nd- DAYSH il-YOM? What day of the week? — AYSH ii-YOM? Today is the fifth of June — il- YOM KHAM-ii ih-ZAY- RAAN Today is Tuesday, etc. — U-YOM it-TLAA-ta Come here — ia-'AAL ta-HON Come quickly — Ia-'AAL V WAAU Go quickly— ROOk 'a-WAAM Who are you? — MEEN int (to a man) MEEN IN-ti (to a woman) MEEN IN-tu (to more than one) What do you want? — SHOO BID-dali, (to » n'* 11 ) 5HOO BID-dik. (to a woman) .YVSH BID-fo<m (to more than one) Bring some drinking water — ZH££B M*4/ lisk-SHURB (to a man) ZHEE-bi MAI Ihh-SHVRB (to a woman) ZHEE-bu MM Ush-SHURB (to more than one) Bring Gome food — ZHEEB l-shi HI- A- fcil (to a man) ZHEE-bi l-shi lit-A-k.il (to a woman) Y.I I Eh I: ti l-shi til- A -kit (to more than one) How far is the camp? — ad- J.1YSH BYlB-'iit il-KAMB How far is the water? — ad* DAYSH bi-TlB-'id il-MAI Whose house is this? — li-MHtN kal-BAYT Weights O'-'o — 2.827 lbs. KEE-LO—i kilogram (2.2046 lbs. avd.) luhn (pronounced like Eng ton)- — 1 ton (metric), or .6 lbs. rati — South Palestine, 6.36 lbs.; North Palestine, 5.653 lbs. O-'EE-a — South Palestine, 0.53 lbs.; North Palestine, 0.471 lbs. 'nn-TAHR — South Palestine, .022 lbs.; North Palestine, .259 lbs. Note: The metric system is in official use in Syria, but the old Arab weights still are used. Roth in Palestine and in Syria these weights vary considerably from place to place and will have to be learned by experience.

Measures DRA.r or PEEK— 26.67 inches (cloth measure) ; 29.84 in. (building and land measure). DU-nttm- — 1099.5056 square yards (land measure), or

600 sq. DRAA'S.

kee-to-Ml-tir — t kilometer ( % at a mile or 3280.S feet). MEEL — mile. MEE-lir— meter (39.37 inches). Distances (t is often futile to try to find out exact distances from the Bedouins, because they have little idea of accurate expression. They will often reply that a place is "two cigarettes away," or about 20 minutes (the time it takes to smoke one cigarette, about to minutes). Or they may reply that a place is so many hours away, by which they mean hours traveling by horse, donkey, or camel. More sophisticated Arabs express distance in meters or kilometers, or perhaps mdes. Money Palestine md — one mil (Palestine), about half a cent; 1,000 mils make

pound.

ta'-REE-la— -5 mils (Palestine), also called mis 'irsh, half a piaster (2 cents). 'iWA— piaster (10 mils J (4 cents; . •ir.SHAYN—2 piasters (8 cents). SHIL-lm — shilling (5 piasters) (20 cents). LEE-ra, WA-ra-'a- — p u u n d (S4.02), nus 'irsh—half a plaster equals ¼ cent.

'irsh—piaster (½ cent).

frank.—franc (5 piasters, equals 2 cents).

'A-shar 'n-ROOSH—10 piasters (5 cents).

khams u-'ish-REEN 'irsh—25 piasters (11 cents).

kham-SEEN 'irsh—50 piasters (23 cents).

LEE-ra, WA-ra-'a—pound (46 cents).

Translation—GREETINGS TO SYRIA AND LEBANON

FROM AMERICA

WE HAVE COME FROM THE NEWEST LAND

OF THE WEST TO THE OLDEST LAND

OF THE EAST

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it is a work of the United States federal government (see 17 U.S.C. 105).

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse