Adventures in Toyland/IV.

The next day she was as good as her word, arriving to the very minute. It was the little Marionette who was not in time. It was quite five minutes before she tripped up the counter and greeted her little friend. The little girl looked at her with some reproach.

"It is you who are late, not I," she said.

"Is it?" replied the little Marionette. "Well, I am ashamed. However, here I am now, so I will begin at once to tell you my tale."

And settling herself down, and smoothing out her beautiful brocade dress, she began without further ado, the story of:

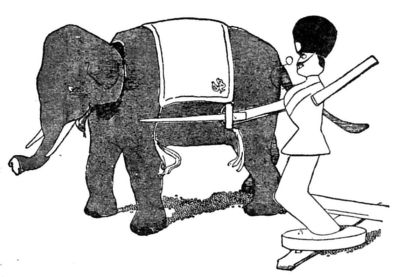

"The Officer and the Elephant."

Amongst all the Toys in the toy-shop, none were so disliked and feared as the twelve Wooden Soldiers who, with an imposing Officer at their head, proudly faced the world in double file.

In the first place, they were intensely proud and vain. They showed this in everything they did. For example, their drill was of the most simple description. It merely consisted in their moving backwards and forwards from one another on a platform of sticks, which could be drawn out or in at pleasure.

This, it will easily be believed, required no great skill or knowledge. Yet, to judge from the pride expressed upon the faces of the Wooden Soldiers as they went through this simple movement, one would have certainly imagined it was exceedingly difficult.

Their foolish pride was also displayed in their manner towards others. No one ventured to ask them even the most civil of questions for fear of receiving a rude answer. Father Christmas one afternoon happened to inquire at the Commanding-officer what time it was.

"Time," he replied, "for little boys to be in bed."

"You might," said the patriarch gravely, "have shown a little respect for the length of my beard and the whiteness of my hairs. 'Tis hardly the way to speak to a man of my years and standing. One, too, who with the decline of the year expects to be at the top of the tree."

But the Officer merely laughed loudly and shrugged his shoulders.

From this instance, which is only one example of many, you will easily understand how the Wooden Soldiers came to be disliked in the toy-shop.

As for the fear they inspired, this was partly owing to the long swords they wore, and partly owing to the boasting way in which they vowed they could use them.

"My men and I really command the whole shop," said the Officer one day. "Moreover, who faces one, faces all, for we all march in the same direction. We not only have our good swords, but we know how to use them. They are sheathed now, but let no one count upon that to offend us. Let but a foolhardy toy dare insult us, and—" here he gave the word of command, and instantly a dozen and one swords sprang from their scabbards.

The lady Dolls shrieked, the Grocer and the Butcher began to put up their shutters with trembling hands; the white, furry Rabbit became a shade whiter; and the corners of the Clown's mouth dropped instead of going up as usual. It was plain that a general panic was felt.

The only Toy that did not appear to be affected was the great gray Elephant lately arrived. He twisted his trunk round thoughtfully, but never changed countenance.

The Officer saw the general terror he had inspired, and both he and his Soldiers were well pleased.

"Besides," he continued, speaking more loudly than before, "if our swords fail us we shall have recourse to gunpowder, which will make short work of our enemies."

The Elephant looked at the Officer and his men.

"I don't see it," he said bluntly.

"I didn't suppose you would," said the Officer scornfully. "Don't speak in such a hurry. The powder I'm speaking of is felt but not seen. It's our last improvement, arrived at by slow degrees. Gunpowder,—smokeless gunpowder,—soundless gunpowder,—invisible gunpowder. Thus we may surround an enemy with enough gunpowder to blow up a town, but they neither see it nor hear it. In fact, they know nothing about it until they are blown up."

This time all the Toys nearly expired with fright! The Elephant only remained, as before, unmoved.

"Invisible gunpowder is more humane in the end," the Officer continued. "You are quite unaware of what is happening until you find yourself in pieces."

"The same thing may happen to yourself, I suppose?" asked the Elephant, in his heavy and clumsy fashion.

"Beg pardon; did anyone speak?" inquired the Officer in the most insulting of voices. For he despised the Elephant and wished to snub him.

"I asked you if the same might not happen to yourself?" the Elephant repeated, regardless of the Officer's attempt to make him appear foolish. "What if the enemy serves you the same way?"

"That difficulty, my good beast," he answered in his most overbearing manner, "is easily disposed of. We have special Soldiers trained to smell gunpowder. We have merely to send out these scouts, and we can trace the gunpowder anywhere within gunshot."

"I don't believe it," said the Elephant.

The Officer at this laughed a grim laugh, truly awful to hear.

"Ha, Ha!" he exclaimed; "do not provoke me too far lest I slay you with my sword. I'm a man of sport, and to do the act would cause me no little diversion. Beware!"

The Elephant made no reply, which induced the Officer to think he had frightened him.

"A great clumsy beast of no spirit," he said to his Soldiers.

"Right, sir," answered the Soldiers.

"Now to drill," he continued sharply. "Attention! Eyes right, eyes left; right movement, left movement; swords out, swords in! Mark—time!"

This last command they were obliged to obey with their heads, their feet being tightly gummed on to the platform. So tightly gummed that they could not get free even when Mortals were not present, and all the Toys were at liberty to speak, walk, and talk. Indeed, nothing but a strong blow could possibly loosen them from their position.

Therefore, when they marched or even took a simple walk they were obliged to march or walk in a body, taking the platform with them. Again, if the Commanding-officer granted leave of absence to one, he was obliged to grant it to all, even to himself, otherwise no one could have taken it.

"Come," said the Officer to the Elephant one day, "you are a bright beast. Let me propound you a mathematical problem. If a herring and a half cost three halfpence, how much would six herrings cost?"

"Just as much as they ought to, if you went to an honest fishmonger," answered the Elephant.

The Officer and his men laughed loudly.

"Capital, capital!" said the bully. "If you distinguish yourself in this way we shall have to make you Mathematical Instructor-in-General to the whole army."

But the Elephant made no reply.

"That's the thickest-skinned animal I ever met," said the Officer to his men.

But herein he made a mistake. The Elephant never forgot an insult, but paid it back upon the first opportunity.

The opportunity, in this case, was not long in arriving; it came, indeed, all too soon for the Officer's taste.

It occurred in this way.

One day a little boy came into the shop and asked to look at some soldiers, upon which the shopwoman showed him the wooden warriors.

"No, I don't like them," he said; "they have to move all the same way at once. It is very stupid of them. Have you no others?"

"Not just at the moment," replied the shopwoman. "We are expecting some more. They should have been here several days ago."

"Then I'll take a train," said the boy. "But it is very funny that you should have such a poor lot of soldiers as these."

"That silly remark will make the Toys less afraid of us," thought the Officer to himself with some alarm. "I shall make the men practise sword-drill in the most open fashion for several hours. This will remind the world that we are not to be trifled with."

But it is one thing to make a resolution and quite another thing to carry it into effect. This the Officer was to experience ere the day was over.

For in putting the Soldiers back into their place the shopwoman happened to hit the Officer with some force against a dolls' house. Being a very hard blow it knocked him off the platform, and, unnoticed by her, he fell on his back upon the counter.

Now came the time for the Elephant's revenge. The Officer fell just under the animal's trunk!

It was, as the Officer at once realized, by no means a pleasant situation. As his men were some yards away from him, and unable to come in a body to his rescue till perhaps too late, the Officer was exceedingly uneasy.

"I had better soothe the monster," he said to himself. Then aloud, and in a pleasant voice: "What a nice handy trunk that is of yours; you must be able to carry so much in it? As for me, I have to travel with a portmanteau, a Gladstone-bag, a hat-box, and a gun-case; it is a terrible nuisance."

He paused, but the Elephant made no reply.

"This is not very pleasant," said the Officer uneasily to himself. "I fear the beast is of a sulky temper. What will happen to me?"

And he lay still, trembling and fearful.

At last the day closed in, the Mortals shut up the shop and left, and the time of the Toys arrived.

The Elephant then addressed the Officer in a slow voice and ponderous manner.

"I feel inclined to trample on you," he remarked.

The Officer closed his eyes with terror; then, half-opening them, he endeavored to look defiantly and speak boldly.

"Pre-pre-sump-tu-tu-ous b-b-b-beast!" he faltered.

The Elephant looked at him threateningly.

"It was on-on-ly my f-f-un!" stammered the Officer, trembling with fear, and all the crimson fading from his cheeks.

"Do you wish me to spare your life?" asked the Elephant.

"It is very valuable," the Officer replied more calmly as he regained courage, and unable to forget his foolish pride even in that awful moment.

"The world can do without it," said the great beast threateningly.

"Spare me!" cried the coward and bully.

The Elephant paused.

"Very good," he answered, "but only upon my own conditions."

"Certainly, certainly," the Officer said in a fawning voice. "Many thanks; any conditions that you may think proper."

After this the Elephant thought for a long while. Then he said:

"These are my conditions. You must submit to let me carry you up and down the counter, stopping before such Toys as I shall see fit. And whenever I stop, you are to announce yourself in these words: 'Good-evening. Have you kicked the coward and the bully? The real genuine article, no imitation. If you have not kicked him already, kick him without delay.'"

"It is too bad of you to require me to say this," the Officer cried, his anger for the moment overcoming his fear. "But then you are not a gentleman. You are—"

"When you have done," interrupted the Elephant, "I will begin."

So saying, and amidst the intense excitement of the other Toys, the Elephant, with his trunk, slowly picked up his fallen foe by the back of the coat and began his ponderous march—so triumphant for himself, so humiliating for the Officer.

The programme was carried out exactly as the Elephant had said it should be, for the great gray beast was a beast of his word. He never made up his mind in a foolish hurry, but having made it up he rarely altered it.

And so it was upon this occasion. After every few steps the huge creature stopped before one or another of the Toys, when the former tyrant was obliged to announce himself as a coward and a bully, and invite a kicking, an invitation which was always accepted, and acted upon with much heartiness.

Finally the avenger laid the Officer on the platform, from which the Wooden Soldiers had been watching with amazement and horror the journey of the Commanding-officer; understanding as they did for the first time the strength of the great beast and afraid to interfere.

Having placed his humble foe in his old position, only upon his back instead of upon his feet, the Elephant with his trunk deliberately knocked over all the Soldiers one after the other. Then he grunted and walked slowly away.

So ended the reign of terror which the Officer and his Soldiers had established over the toy-shop. And so universal was the relief experienced after the strain that had been felt, that the Elephant was everywhere hailed as a Friend to the Public. Indeed, during the remainder of his stay in the shop, he was treated with greater respect and deference than any other toy,—Father Christmas only excepted,—and when he left at Christmas-time, the regret expressed was both loud and sincere.