Alaska Days with John Muir/Chapter 1

THE MOUNTAIN

THUNDER BAY

Deep calm from God enfolds the land;

Light on the mountain top I stand;

How peaceful all, but ah, how grand!

Low lies the bay beneath my feet;

The bergs sail out, a white-winged fleet,

To where the sky and ocean meet.

Their glacier mother sleeps between

Her granite walls. The mountains lean

Above her, trailing skirts of green.

Each ancient brow is raised to heaven:

The snow streams always, tempest-driven,

Like hoary locks, o'er chasms riven

By throes of Earth. But, still as sleep,

No storm disturbs the quiet deep

Where mirrored forms their silence keep.

A heaven of light beneath the sea!

A dream of worlds from shadow free!

A pictured, bright eternity!

The azure domes above, below

(A crystal casket), hold and show,

As precious jewels, gems of snow,

Dark emerald islets, amethyst

Of far horizon, pearls of mist

In pendant clouds, clear icebergs, kissed

By wavelets,—sparkling diamonds rare

Quick flashing through the ambient air.

A ring of mountains, graven fair

In lines of grace, encircles all,

Save where the purple splendors fall

On sky and ocean's bridal-hall.

The yellow river, broad and fleet,

Winds through its velvet meadows sweet—

A chain of gold for jewels meet.

Pours over all the sun's broad ray;

Power, beauty, peace, in one array!

My God, I thank Thee for this day.

I

THE MOUNTAIN

IN the summer of 1879 I was stationed at Fort Wrangell in southeastern Alaska, whence I had come the year before, a green young student fresh from college and seminary—very green and very fresh—to do what I could towards establishing the white man's civilization among the Thlinget Indians. I had very many things to learn and many more to unlearn.

Thither came by the monthly mail steamboat in July to aid and counsel me in my work three men of national reputation—Dr. Henry Kendall of New York; Dr. Aaron L. Lindsley of Portland, Oregon, and Dr. Sheldon Jackson of Denver and the West. Their wives accompanied them and they were to spend a month with us.

Standing a little apart from them as the steamboat drew to the dock, his peering blue eyes already eagerly scanning the islands and mountains, was a lean, sinewy man of forty, with waving, reddish-brown hair and beard, and shoulders slightly stooped. He wore a Scotch cap and a long, gray tweed ulster, which I have always since associated with him, and which seemed the same garment, unsoiled and unchanged, that he wore later on his northern trips. He was introduced as Professor Muir, the Naturalist. A hearty grip of the hand, and we seemed to coalesce at once in a friendship which, to me at least, has been one of the very best things I have known in a life full of

blessings. From the first he was the strongest and most attractive of

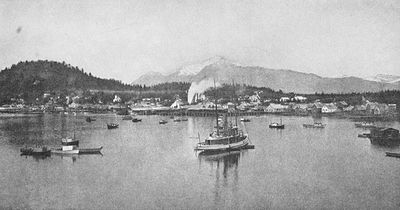

FORT WRANGEL

Near the mouth of the Stickeen—the starting point of the expeditions

Master who was to lead me into enchanting regions of beauty and mystery, which without his aid must forever have remained unseen by the eyes of my soul. I sat at his feet; and at the feet of his spirit I still sit, a student, absorbed, surrendered, as this "priest of Nature's inmost shrine" unfolds to me the secrets of his "mountains of God."

Minor excursions culminated in the chartering of the little steamer Cassiar, on which our party, augmented by two or three friends, steamed between the tremendous glaciers and through the columned canyons of the swift Stickeen River through the narrow strip of Alaska's cup-handle to Glenora, in British Columbia, one hundred and fifty miles from the river's mouth. Our captain was Nat. Lane, a grandson of the famous Senator Joseph Lane of Oregon. Stocky, broad-shouldered, muscular, given somewhat to strange oaths and strong liquids, and eying askance our group as we struck the bargain, he was withal a genial, good-natured man, and a splendid river pilot.

Dropping down from Telegraph Creek (so named because it was a principal station of the great projected trans-American and trans-Siberian line of the Western Union, that bubble pricked by Cyrus Field's cable), we tied up at Glenora about noon of a cloudless day.

"Amuse yourselves," said Captain Lane at lunch. "Here we stay till two o'clock to-morrow morning. This gale, blowing from the sea, makes safe steering through the Canyon impossible, unless we take the morning's calm."

I saw Muir's eyes light up with a peculiar meaning as he glanced quickly at me across the table. He knew the leading strings I was in; how those well-meaning D.D.s and their motherly wives thought they had a special mission to suppress all my self-destructive proclivities toward dangerous adventure, and especially to protect me from "that wild Muir" and his hare-brained schemes of mountain climbing.

"Where is it?" I asked, as we met behind the pilot house a moment later.

He pointed to a little group of jagged peaks rising right up from where we stood—a pulpit in the center of a vast rotunda of magnificent mountains. "One of the finest viewpoints in the world," he said.

"How far to the highest point?"

"About ten miles."

"How high?"

"Seven or eight thousand feet."

That was enough. I caught the D.D.s with guile. There were Stickeen Indians there catching salmon, and among them Chief Shakes, who our interpreter said was "The youngest but the headest Chief of all." Last night's palaver had whetted the appetites of both sides for more. On the part of the Indians, a talk with these "Great White Chiefs from Washington" offered unlimited possibilities for material favor; and to the good divines the "simple faith and childlike docility" of these children of the forest were a constant delight. And then how well their high-flown compliments and flowery metaphors would sound in article and speech to the wondering East! So I sent Stickeen Johnny, the interpreter, to call the natives to another hyou wawa (big talk) and, note-book in hand, the doctors "went gayly to the fray." I set the speeches a-going, and then slipped out to join the impatient Muir.

"Take off your coat," he commanded, "and here's your supper."

Pocketing two hardtacks apiece we were off, keeping in shelter of house and bush till out of sight of the council-house and the flower-picking ladies. Then we broke out. What a matchless climate! What sweet, lung-filling air! Sunshine that had no weakness in it—as if we were springing plants. Our sinews like steel springs, muscles like India rubber, feet soled with iron to grip the rocks. Ten miles? Eight thousand feet? Why, I felt equal to forty miles and the Matterhorn!

"Eh, mon!" said Muir, lapsing into the broad Scotch he was so fond of using when enjoying himself, "ye'll see the sicht o' yer life the day. Ye'll get that'll be o' mair use till ye than a' the gowd o' Cassiar."

From the first, it was a hard climb. Fallen timber at the mountain's foot covered with thick brush swallowed us up and plucked us back. Beyond, on the steeper slopes, grew dwarf evergreens, five or six feet high—the same fir that towers a hundred feet with a diameter of three or four on the river banks, but here stunted by icy mountain winds. The curious blasting of the branches on the side next to the mountain gave them the appearance of long-armed, humpbacked, hairy gnomes, bristling with anger, stretching forbidding arms downwards to bar our passage to their sacred heights. Sometimes an inviting vista through the branches would lure us in, when it would narrow, and at its upper angle we would find a solid phalanx of these grumpy dwarfs. Then we had to attack boldly, scrambling over the obstinate, elastic arms and against the clusters of stiff needles, till we gained the upper side and found another green slope.

Muir led, of course, picking with sure instinct the easiest way. Three hours of steady work brought us suddenly beyond the timber-line, and the real joy of the day began. Nowhere else have I see anything approaching the luxuriance and variety of delicate blossoms shown by these high, mountain pastures of the North. "You scarce could see the grass for flowers." Everything that was marvelous in form, fair in color, or sweet in fragrance seemed to be represented there, from daisies and campanulas to Muir's favorite, the cassiope, with its exquisite little pink-white bells shaped like lilies-of-the-valley and its subtle perfume. Muir at once went wild when we reached this fairyland. From cluster to cluster of flowers he ran, falling on his knees, babbling in unknown tongues, prattling a curious mixture of scientific lingo and baby talk, worshiping his little blue-and-pink goddesses.

"Ah! my blue-eyed darling little did I think to see you here. How did you stray away from Shasta?"

"Well, well! Who'd ’a’ thought that you'd have left that niche in the Merced mountains to come here!"

"And who might you be, now, with your wonder look? Is it possible that you can be (two Latin polysyllables)? You're lost, my dear; you belong in Tennessee."

"Ah! I thought I'd find you, my homely little sweetheart," and so on unceasingly.

So absorbed was he in this amatory botany that he seemed to forget my existence. While I, as glad as he, tagged along, running up and down with him, asking now and then a question, learning something of plant life, but far more of that spiritual insight into Nature's lore which is granted only to those who love and woo her in her great outdoor palaces. But how I anathematized my short-sighted foolishness for having as a student at old Wooster shirked botany for the "more important" studies of language and metaphysics. For here was a man whose natural science had a thorough technical basis, while the superstructure was built of "lively stones," and was itself a living temple of love!

With all his boyish enthusiasm, Muir was a most painstaking student; and any unsolved question lay upon his mind like a personal grievance until it was settled to his full understanding. One plant after another, with its sand-covered roots, went into his pockets, his handkerchief and the "full" of his shirt, until he was bulbing and sprouting all over, and could carry no more. He was taking them to the boat to analyze and compare at leisure. Then he began to requisition my receptacles. I stood it while he stuffed my pockets, but rebelled when he tried to poke the prickly, scratchy things inside my shirt. I had not yet attained that sublime indifference to physical comfort, that Nirvana of passivity, that Muir had found.

Hours had passed in this entrancing work and we were progressing upwards but slowly. We were on the southeastern slope of the mountain, and the sun was still staring at us from a cloudless sky. Suddenly we were in the shadow as we worked around a spur of rock. Muir looked up, startled. Then he jammed home his last handful of plants, and hastened up to where I stood.

"Man!" he said, "I was forgetting. We'll have to hurry now or we'll miss it, we'll miss it."

"Miss what?" I asked.

"The jewel of the day," he answered; "the sight of the sunset from the top."

Then Muir began to slide up that mountain. I had been with mountain climbers before, but never one like him. A deer-lope over the smoother slopes, a sure instinct for the easiest way into a rocky fortress, an instant and unerring attack, a serpent-glide up the steep; eye, hand and foot all connected dynamically; with no appearance of weight to his body—as though he had Stockton's negative gravity machine strapped on his back.

Fifteen years of enthusiastic study among the Sierras had given him the same pre-eminence over the ordinary climber as the Big Horn of the Rockies shows over the Cotswold. It was only by exerting myself to the limit of my strength that I was able to keep near him. His example was at the same time my inspiration and despair. I longed for him to stop and rest, but would not have suggested it for the world. I would at least be game, and furnish no hint as to how tired I was, no matter how chokingly my heart thumped. Muir's spirit was in me, and my "chief end," just then, was to win that peak with him. The impending calamity of being beaten by the sun was not to be contemplated without horror. The loss of a fortune would be as nothing to that!

We were now beyond the flower garden of the gods, in a land of rocks and cliffs, with patches of short grass, caribou moss and lichens

THE MOUNTAIN

| He pointed to a group of jagged peaks rising right up from where we stood—a pulpit in the center of a vast rotunds of magnificent mountains |

came moraine matter, rounded pebbles and boulders, and beyond them the glacier. Once a giant, it is nothing but a baby now, but the ice is still blue and clear, and the crevasses many and deep. And that day it had to be crossed, which was a ticklish task. A misstep or slip might land us at once fairly into the heart of the glacier, there to be preserved in cold storage for the wonderment of future generations. But glaciers were Muir's special pets, his intimate companions, with whom he held sweet communion. Their voices were plain language to his ears, their work, as God's landscape gardeners, of the wisest and best that Nature could offer.

No Swiss guide was ever wiser in the habits of glaciers than Muir, or proved to be a better pilot across their deathly crevasses. Half a mile of careful walking and jumping and we were on the ground again, at the base of the great cliff of metamorphic slate that crowned the summit. Muir's aneroid barometer showed a height of about seven thousand feet, and the wall of rock towered threateningly above us, leaning out in places, a thousand feet or so above the glacier. But the earth-fires that had melted and heaved it, the ice mass that chiseled and shaped it, the wind and rain that corroded and crumbled it, had left plenty of bricks out of that battlement, had covered its face with knobs and horns, had ploughed ledges and cleaved fissures and fastened crags and pinnacles upon it, so that, while its surface was full of man-traps and blind ways, the human spider might still find some hold for his claws.

The shadows were dark upon us, but the lofty, icy peaks of the main range still lay bathed in the golden rays of the setting sun. There was no time to be lost. A quick glance to the right and left, and Muir, who had steered his course wisely across the glacier, attacked the cliff, simply saying, "We must climb cautiously here."

Now came the most wonderful display of his mountain-craft. Had I been alone at the feet of these crags I should have said, "It can't be done," and have turned back down the mountain. But Muir was my "control," as the Spiritists say, and I never thought of doing anything else but following him. He thought he could climb up there and that settled it. He would do what he thought he could. And such climbing! There was never an instant when both feet and hands were not in play, and often elbows, knees, thighs, upper arms, and even chin must grip and hold. Clambering up a steep slope, crawling under an overhanging rock, spreading out like a flying squirrel and edging along an inch-wide projection while fingers clasped knobs above the head, bending about sharp angles, pulling up smooth rock-faces by sheer strength of arm and chinning over the edge, leaping fissures, sliding flat around a dangerous rock-breast, testing crumbly spurs before risking his weight, always going up, up, no hesitation, no pause—that was Muir! My task was the lighter one; he did the head-work, I had but to imitate. The thin fragment of projecting slate that stood the weight of his one hundred and fifty pounds would surely sustain my hundred and thirty. As far as possible I did as he did, took his hand-holds, and stepped in his steps.

But I was handicapped in a way that Muir was ignorant of, and I would not tell him for fear of his veto upon my climbing. My legs were all right—hard and sinewy; my body light and supple, my wind good, my nerves steady (heights did not make me dizzy); but my arms—there lay the trouble. Ten years before I had been fond of breaking colts—till the colts broke me. On successive summers in West Virginia, two colts had fallen with me and dislocated first my left shoulder, then my right. Since that both arms had been out of joint more than once. My left was especially weak. It would not sustain my weight, and I had to favor it constantly. Now and again, as I pulled myself up some difficult reach I could feel the head of the humerus move from its socket.

Muir climbed so fast that his movements were almost like flying, legs and arms moving with perfect precision and unfailing judgment. I must keep close behind him or I would fail to see his points of vantage. But the pace was a killing one for me. As we neared the summit my strength began to fail, my breath to come in gasps, my muscles to twitch. The overwhelming fear of losing sight of my guide, of being left behind and failing to see that sunset, grew upon me, and I hurled myself blindly at every fresh obstacle, determined to keep up. At length we climbed upon a little shelf, a foot or two wide, that corkscrewed to the left. Here we paused a moment to take breath and look around us. We had ascended the cliff some nine hundred and fifty feet from the glacier, and were within forty or fifty feet of the top.

Among the much-prized gifts of this good world one of the very richest was given to me in that hour. It is securely locked in the safe of my memory and nobody can rob me of it—an imperishable treasure. Standing out on the rounded neck of the cliff and facing the southwest, we could see on three sides of us. The view was much the finest of all my experience. We seemed to stand on a high rostrum in the center of the greatest amphitheater in the world. The sky was cloudless, the level sun flooding all the landscape with golden light. From the base of the mountain on which we stood stretched the rolling upland. Striking boldly across our front was the deep valley of the Stickeen, a line of foliage, light green cottonwoods and darker alders, sprinkled with black fir and spruce, through which the river gleamed with a silvery sheen, now spreading wide among its islands, now foaming white through narrow canyons. Beyond, among the undulating hills, was a marvelous array of lakes. There must have been thirty or forty of them, from the pond of an acre to the wide sheet two or three miles across. The strangely elongated and rounded hills had the appearance of giants in bed, wrapped in many-colored blankets, while the lakes were their deep, blue eyes, lashed with dark evergreens, gazing steadfastly heavenward. Look long at these recumbent forms and you will see the heaving of their breasts.

The whole landscape was alert, expectant of glory. Around this great camp of prostrate Cyclops there stood an unbroken semicircle of mighty peaks in solemn grandeur, some hoary-headed, some with locks of brown, but all wearing white glacier collars. The taller peaks seemed almost sharp enough to be the helmets and spears of watchful sentinels. And the colors! Great stretches of crimson fireweed, acres and acres of them, smaller patches of dark blue lupins, and hills of shaded yellow, red, and brown, the many-shaded green of the woods, the amethyst and purple of the far horizon—who can tell it? We did not stand there more than two or three minutes, but the whole wonderful scene is deeply etched on the tablet of my memory, a photogravure never to be effaced.