Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography/Webster, Ebenezer

WEBSTER, Ebenezer, patriot, b. in Kingston, N. H., in 1739; d. in Salisbury (now Franklin), N. H., in 1806. He served in the old French war under Sir Jeffrey Amherst, and in 1761 was one of the first settlers in what is now Franklin, N. H., then the most northern of the New England settlements. There he became a farmer and also kept a tavern. At the opening of the Revolution he led the Salisbury militia to Cambridge, and subsequently saw much service till the close of the war, when he had attained the rank of colonel of militia. He was a member of the lower branch of the legislature for several years, served also in the state senate, and from 1791 till his death was judge of the court of common pleas of Hillsborough county, N. H. — His son, Ezekiel, lawyer, b. in Salisbury, N. H., 11 March, 1780; d. in Concord, N. H., 10 April, 1829, was graduated at Dartmouth in 1804, studied law, and rose to eminence at the bar. He was also a member for several years of the New Hampshire legislature. His death resulted suddenly from disease of the heart while he was trying a case. — Another son, Daniel, statesman, b. in Salisbury (now Franklin), N. H., 18 Jan., 1782; d. in Marshfield, Mass., 24 Oct., 1852, was the second son of Ebenezer Webster by his second wife, Abigail Eastman. He seemed so puny and sickly as an infant that it was thought he would not live to grow up. He was considered too delicate for hard work on the farm, and was allowed a great deal of time for play. Much of this leisure he spent in fishing and hunting, or in roaming about the woods, the rest in reading. In later life he could not remember when he learned to read. As a child his thirst for knowledge was insatiable; he read every book that came within reach, and conned his favorite authors until their sentences were in great part stored in his memory. In May, 1796, he was sent to Exeter academy, where he made rapid progress with his studies, but was so overcome by shyness that he found it impossible to stand up and “speak pieces” before his school-mates. In spite of this timidity, some of his natural gifts as an orator had already begun to show themselves. His great, lustrous eyes and rich voice, with its musical intonations, had already exerted a fascination upon those who came within their range; passing teamsters would stop, and farmers pause, sickle in hand, to hear him recite verses of poetry or passages from the Bible. In February, 1797, his father sent him to Boscawen, where he continued his studies under the tuition of the Rev. Samuel Wood. Although Ebenezer Webster found it difficult, by unremitting labor and strictest economy, to support his numerous family, he still saw such signs of promise in Daniel as to convince him that it was worth while, at whatever sacrifice, to send him to college. In view of this decision, he took him from school, to hasten his preparation under a private tutor, and on the journey to Boscawen he informed Daniel of his plans. The warm-hearted boy, who had hardly dared hope for such good fortune, and keenly felt the sacrifice it involved, laid his head upon his father's shoulder and burst into tears. After six months with his tutor he had learned enough to fulfil the slender requirements of those days for admission to Dartmouth, where he was duly graduated in 1801. At college, although industrious and punctual in attendance and soon found to be very quick at learning, he was not regarded as a thorough scholar. He had not, indeed, the scholarly temperament — that rare combination of profound insight, sustained attention, microscopic accuracy, iron tenacity, and disinterested pursuit of truth — which characterizes the great scientific discoverer or the great historian. But, while he had not these qualities in perfect combination — and no one knew this better than Mr. Webster himself — there was much about him that made him more interesting and remarkable, even at that early age, than if he had been consummate in scholarship. He was capable of great industry, he seized an idea with astonishing quickness, his memory was prodigious, and for power of lucid and convincing statement he was unrivalled. With these rare gifts he possessed that supreme poetic quality that defies analysis, but is at once recognized as genius. He was naturally, therefore, considered by tutors and fellow-students the most remarkable man in the college, and the position of superiority thus early gained was easily maintained by him through life and wherever he was placed. While at college he conquered or outgrew his boyish shyness, so as to take pleasure in public speaking, and his eloquence soon attracted so much notice that in 1800 the townspeople of Hanover selected this undergraduate to deliver the Fourth-of-July oration. It has been well pointed out by Henry Cabot Lodge that “the enduring work which Mr. Webster did in the world, and his meaning and influence in American history, are all summed up in the principles enunciated in that boyish speech at Hanover,” which “preached love of country, the grandeur of American nationality, fidelity to the constitution as the bulwark of nationality, and the necessity and the nobility of the union of the states.” After leaving college, Mr. Webster began studying law in the office of Thomas W. Thompson, of Salisbury, who was afterward U. S. senator. Some time before this he had made up his mind to help his elder brother, Ezekiel, to go through college, and for this purpose he soon found it necessary to earn money by teaching school. After some months of teaching at Fryeburg, Me., he returned to Mr. Thompson's office. In July, 1804, he went to Boston in search of employment in some office where he might complete his studies. He there found favor with Christopher Gore, who took him into his office as student and clerk. In March, 1805, Mr. Webster was admitted to the bar, and presently he began practising his profession at Boscawen. In 1807, having acquired a fairly good business, he turned it over to his brother, Ezekiel, and removed to Portsmouth, where his reputation grew rapidly, so that he was soon considered a worthy antagonist to Jeremiah Mason, one of the ablest lawyers this country has ever produced. In June, 1808, he married Miss Grace Fletcher, of Hopkinton, N. H.

His first important political pamphlet, published that year, was a criticism on the embargo. In 1812, in a speech before the Washington benevolent society at Portsmouth, he summarized the objections of the New England people to the war just

declared against Great Britain. He was immediately afterward chosen delegate to a convention of the people of Rockingham county, and drew up the so-called “Rockingham Memorial,” addressed toPresident Madison, which contained a formal protest against the war. In the following autumn he was elected to congress, and on taking his seat, in May, 1813, he was placed on the committee on foreign relations. His first step in congress was the .introduction of a series of resolutions aimed at the president, and calling for a statement of the time and manner in which Napoleon's pretended revocation of his decrees against American shipping had been announced to the United States. His first great speech, 14 Jan., 1814, was in opposition to the bill for encouraging enlistments, and at the close of that year he opposed Sec. Monroe's measures for enforcing what was known as the “draft of 1814.” Mr. Webster's attitude toward the administration was that of the Federalist party to which he belonged; but he did not go so far as the leaders of that party in New England. He condemned the embargo as more harmful to ourselves than to the enemy, as there is no doubt it was; he disapproved the policy of invading Canada, and maintained that our wisest course was to increase the strength of the navy, and on these points history will probably judge him to have been correct. But in his opinion, that the war itself was unnecessary and injurious to the country, he was probably, like most New Englanders of that time, mistaken. Could he have foreseen and taken into account the rapid and powerful development of national feeling in the United States which the war called forth, it would have modified his view, for it is clear that the war party, represented by Henry Clay and his friends, was at that moment the truly national party, and Mr. Webster's sympathies were then, as always, in favor of the broadest nationalism, and entirely opposed to every sort of sectional or particularist policy. This broad, national spirit, which was strong enough in the two Adamses to sever their connection with the Federalists of New England, led Mr. Webster to use his influence successfully to keep New Hampshire out of the Hartford convention. In the 13th congress, however, he voted 191 times on the same side with Timothy Pickering, and only 4 times on the opposite side. In this and the next congress the most important work done by Mr. Webster was concerned with the questions of currency and a national bank. He did good service in killing the pernicious scheme for a bank endowed with the power of issuing irredeemable notes and obliged to lend money to the government. He was disposed to condemn outright the policy of allowing the government to take part in the management of the bank. He also opposed a protective tariff, but, by supporting Mr. Calhoun's bill for internal improvements, he put himself on record as a loose constructionist. His greatest service was unquestionably his resolution of 26 April, 1816, requiring that all payments to the national treasury must be made in specie or its equivalents. This resolution, which he supported in a very powerful speech, was adopted the same day by a large majority, and its effect upon the currency was speedily beneficial. In the course of this session he declined, with grim humor, a challenge sent him by John Randolph.

|

In June, 1816, he removed to Boston, and at the expiration of his second term in congress, 4 March, 1817, he retired for a while to private life. His reason for retiring was founded in need of money and the prospect of a great increase in his law-practice. On his removal to Boston this prospect was soon realized in an income of not less than $20,000 a year. One of the first cases upon which he was now engaged was the famous Dartmouth college affair. While Mr. Webster's management of this case went far toward placing him at the head of the American bar, the political significance of its decision was such as to make it an important event in the history of the United States. It shows Mr. Webster not only as a great constitutional lawyer and consummate advocate, but also as a powerful champion of Federalism. In its origin Dartmouth college was a missionary school for Indians, founded in 1754 by the Rev. Eleazar Wheelock, at Lebanon. Conn. After a few years funds were raised by private subscription for the purpose of enlarging the school into a college, and as the Earl of Dartmouth had been one of the chief contributors, Dr. Wheelock appointed him and other persons trustees of the property. The site of the college was fixed in New Hampshire, and a royal charter in 1769 created it a perpetual corporation. The charter recognized Wheelock as founder, and appointed him president, with power to name his successor, subject to confirmation by the trustees. Dr. Wheelock devised the presidency to his son, John Wheelock, who accordingly became his successor. The charter, in expressly forbidding the exclusion of any person on account of his religious belief, reflected the broad and tolerant disposition of Dr. Wheelock, who was a liberal Presbyterian, and as such had been engaged in prolonged controversy with that famous representative of the strictest Congregationalism, Dr. Joseph Bellamy. In 1793 Bellamy's pupil, Nathaniel Niles, became a trustee of Dartmouth, and between him and John Wheelock the old controversy was revived and kept up with increasing bitterness for several years, dividing the board of trustees into two hostile parties. At length, in 1809, the party opposed to President Wheelock gained a majority in the board, and thus became enabled in various ways to balk and harass the president, until in 1815 the quarrel broke forth into a war of pamphlets and editorial articles that convulsed the whole state of New Hampshire. The Congregational church was at that time the established church in New Hampshire, supported by taxation, and the Federalist party found its strongest adherents among the members of that church. Naturally, therefore, the members of other churches, and persons opposed on general principles to the establishment of a state church, were inclined to take sides with the Republicans. In 1815 President Wheelock petitioned the legislature for a committee to investigate the conduct of the trustees, whom he accused of various offences, from intolerance in matters of religion to improper management of the funds. Thus the affair soon became a party question, in which the Federalists upheld the trustees, while the Republicans sympathized with the president. The legislature granted the petition for a committee, but the trustees forthwith, in a somewhat too rash spirit of defiance, deposed Mr. Wheelock and chose a new president, the Rev. Francis Brown. In the ensuing state election Mr. Wheelock and his sympathizers went over to the Republicans, who thus succeeded in electing their candidate for governor, with a majority of the legislature. In June, 1816, the new legislature passed an act reorganizing the college, and a new board of trustees was at once appointed by the governor. Judge Woodward, secretary of the old board, went over to the new board, and became its secretary, taking with him the college seal. The new board proceeded to expel the old board, which forthwith brought suit against Judge Woodward in an action of trover for the college seal. The case was tried in May, 1817, with those two great lawyers, Jeremiah Mason and Jeremiah Smith, as counsel for the plaintiffs. It was then postponed till September, when Mr. Webster was secured by the plaintiffs as an additional counsel. The plaintiffs contended that, in the case of a corporation chartered for private uses, any alleged misconduct of the trustees was properly a question for the courts, and not for the legislature, which in meddling with such a question plainly transcended its powers. Their chief reliance was upon this point, but they also contended that the act of legislature reorganizing the college was an act impairing the obligation of a contract, and therefore a violation of the constitution of the United States. The state court at Exeter decided against the plaintiffs, and the point last mentioned enabled them to carry up their case to the supreme court of the United States. As the elder counsel were unable to go to Washington, it fell to Mr. Webster to conduct the case, which was tried in March, 1818. Mr. Webster argued that the charter of Dartmouth college created a private corporation for administering a charity; that in the administration of such uses the trustees have a recognized right of property; that the grant of such a charter is a contract between the sovereign power and the grantees, and descends to their successors; and that, therefore, the act of the New Hampshire legislature, in taking away the government from one board of trustees and conferring it upon another, was a violation of contract. These points were defended by Mr. Webster with masterly cogency, and re-enforced by illustrations calculated to appeal to the Federalist sympathies of the chief justice. He possessed in the highest degree the art of so presenting a case that the mere statement seemed equivalent to demonstration, and never did he exhibit that art in greater perfection or use it to better purpose than in this argument. A few sentences at the close, giving utterance to deep emotion, left judges and audience in tears. The decision, rendered in the autumn, sustained Mr. Webster and set aside the act of the legislature as unconstitutional. It was one of those far-reaching decisions in which the supreme court, under John Marshall, fixed the interpretation of the constitution in such wise as to add greatly to its potency as a fundamental instrument of government. The clause prohibiting state legislation in impairment of contracts, like most such general provisions, stood in need of judicial decisions to determine its scope. By bringing under the protection of this clause every charter granted by a state, the decision in the Dartmouth college case went further perhaps than any other in our history toward limiting state sovereignty and extending the jurisdiction of the Federal supreme court.

In the Massachusetts convention of 1820 for revising the state constitution Mr. Webster played an important part. He advocated with success the abolition of religious tests for office-holders, and in a speech in support of the feature of property-representation in the senate he examined the theory and practice of bicameral legislation. His discussion of that subject is well worthy of study. In the same year, at the celebration of the second centennial of the landing of the Pilgrims, his commemorative oration was one of the noblest ever delivered. In 1825, on the laying of the corner-stone of Bunker Hill monument (see illustration), he attained still higher perfection of eloquence; and one year later, on the deaths of Adams and Jefferson, his eulogy upon those statesmen completed a trio of historical addresses unsurpassed in splendor. The spirit of these orations is that of the broadest patriotism, enlightened by a clear perception of the fundamental importance of the Federal union between the states and an ever-present consciousness of the mighty future of our country and its moral significance in the history of the world. Such topics have often been treated as commonplaces and made the theme of vapid rhetoric; but under Daniel Webster's treatment they acquired a philosophical value and were fraught with most serious and earnest meaning. These orations were conceived in a spirit of religious devotion to the Union, and contributed powerfully toward awakening such a sentiment in those who read them afterward, while upon those who heard them from the lips of the majestic speaker the impression was such as could never be effaced. The historian must assign to them a high place among the literary influences that aroused in the American people a sentiment of union strong enough to endure the shock of civil war.

In 1822 Mr. Webster was elected to congress from the Boston district, and he was twice re-elected by a popular vote that was almost unanimous. When he took his seat in congress in December, 1823, the speaker, Henry Clay, appointed him chairman of the judiciary committee. In that capacity he prepared and carried through the “Crimes act,” which was substantially a thorough remodelling of the criminal jurisprudence of the United States. The preparation of this bill showed in the highest degree his constructive genius as a legislator, while in carrying it through congress his parliamentary skill and persuasiveness in debate were equally conspicuous. In 1825 he prepared a bill for increasing the number of supreme court judges to ten, for making ten Federal circuits, and otherwise strengthening the working capacity of the court; but this bill, after passing the house, was lost in the senate. Of his two most celebrated speeches in congress during this period, the first was on the revolution in Greece. Mr. Webster moved, 19 Jan., 1824, the adoption of his own resolution in favor of making provision for a commissioner to Greece should President Monroe see fit to appoint one. In his speech on this occasion he set forth the hostility of the American people to the principles, motives, and methods of the “Holy Alliance,” and their sympathy with such struggles for self-government as that in which the Greeks were engaged. The resolution was not adopted, but Mr. Webster's speech made a profound impression at home and abroad. It was translated into several European languages, and called forth much foreign comment. The other great speech, delivered on 1 and 2 April, 1824, was what is commonly called his “free-trade speech.” A bill had been introduced for revising the tariff in such a way as to extend the operation of the protective system. In this speech Mr. Webster found fault with the phrase “American policy,” as applied by Mr. Clay to the system of high protective duties. “If names are thought necessary,” said Mr. Webster, “it would be well enough, one would think, that the name should be in some measure descriptive of the thing; and since Mr. Speaker denominates the policy which he recommends a 'new policy in this country'; since he speaks of the present measure as a new era in our legislation; since he professes to invite us to depart from our accustomed course, to instruct ourselves by the wisdom of others, and to adopt the policy of the most distinguished foreign states — one is a little curious to know with what propriety of speech this imitation of other nations is denominated an 'American policy,' while, on the contrary, a preference for our own established System, as it now actually exists and always has existed, is called a 'foreign policy.' This favorite American policy is what America has never tried; and this odious foreign policy is what, as we are told, foreign states have never pursued. Sir, that is the truest American policy which shall most usefully employ American capital and American labor.” After this exordium, Mr. Webster went on to give a masterly exposition of some of the elementary theorems of political economy and a survey, at once comprehensive and accurate, of the condition of American industry at the time. He not only attacked Mr. Clay's policy on broad national grounds, but also showed more specifically that it was likely to prove injurious to the maritime commerce in which the New England states had so long taken the lead; and he concluded by characterizing that policy as “so burdensome and so dangerous to the interest which has steadily enriched, gallantly defended, and proudly distinguished us, that nothing can prevail upon me to give it my support.” Upon this last clause of his speech he was afterward enabled to rest a partial justification of his change of attitude toward the tariff. The other chief incidents in his career in the house of representatives were his advocacy of a national bankrupt law, his defence of William H. Crawford, secretary of the treasury, against sundry charges brought against him by Ninian Edwards (q. v.) lately senator from Illinois, and his defence of President Adams's policy in the matter of Georgia and the Creek Indians.

|

In politics Mr. Webster occupied at this time an independent position. The old Federalist party, to which he had formerly belonged, was completely broken down, and the new National Republican party, with its inheritance of many of the principles, motives, and methods of the Federalists, was just beginning to take shape under the leadership of Adams and Clay. Between these eminent statesmen and Mr. Webster the state of feeling was not such as to insure cordial co-operation, but in their views of government there was similarity enough to bring them together in opposition to the new Democratic party represented by Jackson, Benton, and Van Buren. With the extreme southern views of Crawford and Calhoun it was impossible that he should sympathize, although his personal relations with those leaders were quite friendly, and after the death of Calhoun, the noblest eulogium upon his character and motives was made by Mr. Webster. There is a sense in which all American statesmen may be said to be intellectually the descendants and disciples either of Jefferson or of Hamilton, and as a representative follower of Hamilton, Mr. Webster was sure to be drawn rather toward Clay than toward Jackson. The course of industrial events in New England was such as to involve changes of opinion in that part of the country, which were soon reflected in a complete reversal of Mr. Webster's attitude toward the tariff. In 1827 he was elected to the U. S. senate. In that year an agitation was begun by the woollen-manufacturers, which soon developed into a promiscuous scramble among different industries for aid from government, and finally resulted in the tariff of 1828. That act, which was generally known at the time as “the tariff of abominations,” was the first extreme application of the protective system in our Federal legislation. When the bill was pending before the senate in April, 1828, Mr. Webster made a memorable speech, in which he completely abandoned the position he had held in 1824, and from this time forth he was a supporter of the policy of Mr. Clay and the protectionists. For this change of attitude he was naturally praised by his new allies, who were glad to interpret it as a powerful argument in favor of their views. By every one else he was blamed, and this speech has often been cited, together with that of 7 March, 1850, as proving that Mr. Webster was governed by unworthy motives and wanting in political principle. The two cases, as we shall see, are not altogether parallel. Probably neither admits of entire justification, but in neither case did Mr. Webster attempt to conceal or disguise his real motives. In 1828 he frankly admitted that the policy of protection to manufactures by means of tariff duties was a policy of which he had disapproved, whether as a political economist or as a representative of the interests of New England. Against his own opposition and that of New England, the act of 1824 had passed. “What, then, was New England to do? . . . Was she to hold out forever against the course of the government, and see herself losing on one side and yet make no effort to sustain herself on the other? No, sir. Nothing was left for New England but to conform herself to the will of others. Nothing was left to her but to consider that the government had fixed and determined its own policy; and that policy was protection.” In other words, the tariff policy adopted at Washington, while threatening the commercial interests of New England, had favored the investment of capital in manufactures there, and it was not becoming in a representative of New England to take part in disturbing the new arrangement of things. This argument, if pushed far enough, would end in the doctrine — now apparently obsolete, though it has often been attacked and defended — that a senator is simply the minister of his state in congress. With Mr. Webster it went so far as to modify essentially his expressions of opinion as to the constitutionality of protective legislation. He had formerly been inclined to interpret the constitution strictly upon this point, but in 1828 and afterward his position was that of the loose constructionists. Here the strong Federalist bias combined with that temperament which has sometimes been called “opportunism” to override his convictions upon the economic

merits of the question.This tariff of 1828 soon furnished an occasion for the display of Mr. Webster's strong Federalist spirit in a way that was most serviceable for his country and has earned for him undying fame as an orator and statesman. It led to the distinct announcement of the principles of nullification by the public men of South Carolina, with Mr. Calhoun at their head. During President Jackson's first term the question as to nullification seemed to occupy everybody's thoughts and had a way of intruding upon the discussion of all other questions. In December, 1829, Samuel A. Foote, of Connecticut, presented to the senate a resolution inquiring into the expediency of limiting the sales of the public lands to those already in the market, besides suspending the surveys of the public lands and abolishing the office of surveyor-general. The resolution was quite naturally resented by the western senators as having a tendency to check the growth of their section of the country. The debate was opened by Mr. Benton, and lasted several weeks, with increasing bitterness. The belief in the hostility of the New England states toward the west was shared by many southern senators, who desired to unite south and west in opposition to the tariff. On 19 Jan., 1830, Robert Y. Hayne, of South Carolina, attacked the New England states, accusing them of aiming by their protective policy at aggrandizing themselves at the expense of all the rest of the Union. On the next day Mr. Webster delivered his “first speech on Foote's resolution,” in which he took up Mr. Hayne's accusations and answered them with great power. This retort provoked a long and able reply from Mr. Hayne, in which he not only assailed Mr. Webster and Massachusetts and New England, but set forth quite ingeniously and elaborately the doctrines of nullification. In view of the political agitation then going on in South Carolina, it was felt that this speech would work practical mischief unless it should meet with instant refutation. It was finished on 25 Jan., and on the next two days Mr. Webster delivered his “second speech on Foote's resolution,” better known in history as the “Reply to Hayne.” The debate had now lasted so long that people had come from different parts of the country to Washington to hear it, and on 26 Jan. the crowd not only filled the galleries and invaded the floor of the senate-chamber, but occupied all the lobbies and entries within hearing and even beyond. In the first part of his speech Mr. Webster replied to the aspersions upon himself and New England; in the second part he attacked with weighty argument and keen-edged sarcasm the doctrine of nullification. He did not undertake to deny the right of revolution as a last resort in cases with which legal and constitutional methods are found inadequate to deal; but he assailed the theory of the constitution maintained by Calhoun and his followers, according to which nullification was a right, the exercise of which was compatible with loyal adherence to the constitution. His course of argument was twofold; he sought to show, first, that the theory of the constitution as a terminable league or compact between sovereign states was unsupported by the history of its origin, and, secondly, that the attempt on the part of any state to act upon that theory must necessarily entail civil war or the disruption of the Union. As to the sufficiency of his historical argument there has been much difference of opinion. The question is difficult to deal with in such a way as to reach an unassailable conclusion, and the difficulty is largely due to the fact that in the various ratifying conventions of 1787-'9 the men who advocated the adoption of the constitution did not all hold the same opinions as to the significance of what they were doing. There was great divergence of opinion, and plenty of room for antagonisms of interpretation to grow up as irreconcilable as those of Webster and Calhoun. If the South Carolina doctrine distorted history in one direction, that of Mr. Webster probably departed somewhat from the record in the other; but the latter was fully in harmony with the actual course of our national development, and with the increased and increasing strength of the sentiment of union at the time when it was propounded with such powerful reasoning and such magnificent eloquence in the “Reply to Hayne.” As an appeal to the common sense of the American people, nothing could be more masterly than Mr. Webster's demonstration that nullification practically meant revolution, and their unalterable opinion of the soundness of his argument was amply illustrated when at length the crisis came which he deprecated with such, intensity of emotion in his concluding sentences. To some of the senators who listened to the speech, as, for instance, Thomas H. Benton, it seemed as if the passionate eloquence of its close concerned itself with imaginary dangers never likely to be realized; but the event showed that Mr. Webster estimated correctly the perilousness of the doctrine against which he was contending. For genuine oratorical power, the “Reply to Hayne” is probably the greatest speech that has been delivered since the oration of Demosthenes on the crown. The comparison is natural, as there are points in the American orator that forcibly remind one of the Athenian. There is the fine sense of proportion and fitness, the massive weight of argument due to transparent clearness and matchless symmetry of statement, and along with the rest a truly Attic simplicity of diction. Mr. Webster never indulged in mere rhetorical flights; his sentences, simple in structure and weighted with meaning, went straight to the mark, and his arguments were so skilfully framed that while his most learned and critical hearers were impressed with a sense of their conclusiveness, no man of ordinary intelligence could fail to understand them. To these high qualifications of the orator was added such a physical presence as but few men have been endowed with. Mr. Webster's appearance was one of unequalled dignity and power, his voice was rich and musical, and the impressiveness of his delivery was enhanced by the depth of genuine manly feeling with which he spoke. Yet while his great speeches owed so much of their overpowering effect to the look and manner of the man, they were at the same time masterpieces of literature. Like the speeches of Demosthenes, they were capable of swaying the reader as well as the hearer, and their effects went far beyond the audience and far beyond the occasion of their delivery. In all these respects the “Reply to Hayne” marks the culmination of Mr. Webster's power as an orator. Of all the occasions of his life, this encounter with the doctrine of nullification on its first bold announcement in the senate was certainly the greatest, and the speech was equal to the occasion. It struck a chord in the heart of the American people which had not ceased to vibrate when the crisis came thirty years later. It gave articulate expression to a sentiment of loyalty to the Union that went on growing until the American citizen was as prompt to fight for the Union as the Mussulman for his prophet or the cavalier for his king. It furnished, moreover, a clear and comprehensive statement of the theory by which that sentiment of loyalty was justified. Of the men who in after-years gave up their lives for the Union, doubtless the greater number had as school-boys declaimed passages from this immortal speech and caught some inspiration from its fervid patriotism. Probably no other speech ever made in congress has found so many readers or exerted so much influence in giving shape to men's thoughts.

Three years afterward Mr. Webster returned to struggle with nullification, being now pitted against the master of that doctrine instead of the disciple. In the interval South Carolina had attempted to put the doctrine into practice, and had been resolutely met by President Jackson with his proclamation of 10 Dec., 1832. In response to a special message from the president, early in January, 1833, the so-called “Force bill,” empowering the president to use the army and navy, if necessary, for enforcing the revenue laws in South Carolina, was reported in the senate. The bill was opposed by Democrats who did not go so far as to approve of nullification, but the defection of these senators was more than balanced by the accession of Mr. Webster, who upon this measure came promptly to the support of the administration. For this, says Benton, “his motives . . . were attacked, and he was accused of subserviency to the president for the sake of future favor. At the same time all the support which he gave to these measures was the regular result of the principles which he laid down against nullification in the debate with Mr. Hayne, and he could not have done less without being derelict to his own principles then avowed. It was a proud era in his life, supporting with transcendent ability the cause of the constitution and of the country, in the person of a chief magistrate to whom he was politically opposed, bursting the bonds of party at the call of duty, and displaying a patriotism worthy of admiration and imitation. Gen. Jackson felt the debt of gratitude and admiration which he owed him; the country, without distinction of party, felt the same. . . . He was the colossal figure on the political stage during that eventful time; and his labors, splendid in their day, survive for the benefit of distant posterity” (“Thirty Years' View,” i., 334). The support of the president's policy by Mr. Webster, and its enthusiastic approval by nearly all the northern and a great many of the southern people, seems to have alarmed Mr. Calhoun, probably not so much for his personal safety as for the welfare of his nullification schemes. The story that he was frightened by the rumor that Jackson had threatened to begin by arresting him on a charge of treason is now generally discredited. He had seen enough, however, to convince him that the theory of peaceful nullification was not now likely to be realized. It was not his aim to provoke an armed collision, and accordingly a momentary alliance was made between himself and Mr. Clay, resulting in the compromise tariff bill of 12 Feb., 1833. Only four days elapsed between Mr. Webster's announcement of his intention to support the president and the introduction of this compromise measure. Mr. Webster at once opposed the compromise, both as unsound economically and as an unwise and dangerous concession to the threats of the nullifiers. At this point the Force bill was brought forward, and Mr. Calhoun made his great speech, 15-16 Feb., in support of the resolutions he nad introduced on 22 Jan., affirming the doctrine of nullification. To this Mr. Webster replied, 16 Feb., with his speech entitled “The Constitution not a Compact between Sovereign States,” in which he supplemented and re-enforced the argument of the “Reply to Hayne.” Mr. Calhoun's answer, 26 Feb., was perhaps the most powerful speech he ever delivered, and Mr. Webster did not reply to it at length. The burden of the discussion was what the American people really did when they adopted the Federal constitution. Did they simply create a league between sovereign states, or did they create a national government, which operates immediately upon individuals, and, without superseding the state governments, stands superior to them, and claims a prior allegiance from all citizens? It is now plain to be seen that in point of fact they did create such a national government; but how far they realized at the outset what they were doing is quite another question. Mr. Webster's main conclusion was sustained with colossal strength; but his historical argument was in some places weak, and the weakness is unconsciously betrayed in a disposition toward wire-drawn subtlety, from which Mr. Webster was usually quite free. His ingenious reasoning upon the meaning of such words as “compact” and “accede” was easily demolished by Mr. Calhoun, who was, however, more successful in hitting upon his adversary's vulnerable points than in making good his own case. In fact, the historical question was not really so simple as it presented itself to the minds of those two great statesmen. But in whatever way it was to be settled, the force of Mr. Webster's practical conclusions remained, as he declared in the brief rejoinder with which he ended the discussion: “Mr. President, turn this question over and present it as we will — argue it as we may — exhaust upon it all the fountains of metaphysics — stretch over it all the meshes of logical or political subtlety — it still comes to this: Shall we have a general government? Shall we continue the union of the states under a government instead of a league? This is the upshot of the whole matter; because, if we are to have a government, that government must act like other governments, by majorities; it must have this power, like other governments, of enforcing its own laws and its own decisions; clothed with authority by the people and always responsible to the people, it must be able to hold its course unchecked by external interposition. According to the gentleman's views of the matter, the constitution is a league; according to mine, it is a regular popular government. This vital and all-important question the people will decide, and in deciding it they will determine whether, by ratifying the present constitution and frame of government, they meant to do nothing more than to amend the articles of the old confederation.” As the immediate result of the debates, both the Force bill and the Compromise tariff bill were adopted, and this enabled Mr. Calhoun to maintain that the useful and conservative character of nullification had been demonstrated, since the action of South Carolina had, without leading to violence, led to such modifications of the tariff as she desired. But the abiding result was, that Webster had set forth the theory upon which the Union was to be preserved, and that the administration, in acting upon that theory, had established an extremely valuable precedent for the next administration that should be called upon to meet a similar crisis.

The alliance between Mr. Webster and President

Jackson extended only to the question of

maintaining the Union. As an advocate of the policy

of a national bank, a protective tariff, and internal

improvements, Mr. Webster's natural place was by

the side of Mr. Clay in the Whig party, which was

now in the process of formation. He was also at

one with both the northern and the southern

sections of the Whig party in opposition to what

Mr. Benton called the “demos krateo” principle,

according to which the president, in order to carry

out the “will of the people,” might feel himself

authorized to override the constitutional limitations

upon his power. This was not precisely what

Mr. Benton meant by his principle, but it was the

way in which it was practically illustrated in

Jackson's war against the bank. In the course of

this struggle Mr. Webster made more than sixty

speeches, remarkable for their wide and accurate

knowledge of finance. His consummate mastery

of statement is nowhere more thoroughly exemplified

than in these speeches. Constitutional questions

were brought up by Mr. Clay's resolutions

censuring the president for the removal of the

deposits, and for dismissing William J. Duane,

secretary of the treasury. In reply to the resolutions,

President Jackson sent to the senate his remarkable

“Protest,” in which he maintained that in the

mere discussion of such resolutions that body transcended

its constitutional prerogatives, and that

the president is the “direct representative of the

American people,” charged with the duty, if need

be, of protecting them against the usurpations of

congress. The Whigs maintained, with much

truth, that this doctrine, if carried out in all its

implications, would push democracy to the point

where it merges in Cæsarism. It was now that

the opposition began to call themselves Whigs, and

tried unsuccessfully to stigmatize the president's

supporters as “Tories.” Mr. Webster's speech on

the president's protest, 7 May, 1834, was one of

great importance, and should be read by every

student of our constitutional history. In another

elaborate speech, 16 Feb., 1885, he tried to show

that under a proper interpretation of the constitution

the power of removal, like the power of

appointment, was vested in the president and senate

conjointly, and that “the decision of congress in

1789, which separated the power of removal from

the power of appointment, was founded on an

erroneous construction of the constitution.” But

subsequent opinion has upheld the decision of 1789,

leaving the speech to serve as an illustration of

the way in which, under the stress of a particular

contest, the Whigs were as ready to strain the

constitution in one direction as the Democrats were

inclined to bend it in another. An instance of the

latter kind was Mr. Benton's expunging resolution,

against which Mr. Webster emphatically protested.

About this time Mr. Webster was entertaining thoughts of retiring, for a while at least, from public life. As he said, in a letter to a friend, he had not for fourteen years had leisure to attend to his private affairs, or to become acquainted by travel with his own country. This period had not, however, been entirely free from professional work. It was seldom that Mr. Webster took part in criminal trials, but in this department of legal practice he showed himself qualified to take rank with the greatest advocates that have ever addressed a jury. His speech for the prosecution, on the trial of the murderers of Capt. Joseph White, at Salem, in August, 1830, has been pronounced superior to the finest speeches of Lord Erskine. In the autumn of 1824, while driving in a chaise with his wife from Sandwich to Boston, he stopped at the beautiful farm of Capt. John Thomas, by the sea-shore at Marshfield. For the next seven years his family passed their summers at this place as guests of Capt. Thomas; and, as the latter was growing old and willing to be eased of the care of the farm, Mr. Webster bought it of him in the autumn of 1831. Capt. Thomas continued to live there until his death, in 1837, as Mr. Webster's guest. For the latter it became the favorite home whither he retired in the intervals of public life. It was a place, he said, where he “could go out every day in the year and see something new.” Mr. Webster was very fond of the sea. He had also a passion for country life, for all the sights and sounds of the farm, for the raising of fine animals, as well as for hunting and fishing. The earlier years of Mr. Webster's residence at Marshfield, and of his service in the U. S. senate, witnessed some serious events in his domestic life. Death removed his wife, 21 Jan., 1828, and his brother Ezekiel, 10 April, 1829. In December, 1829, he married Miss Caroline Le Roy, daughter of a wealthy merchant in New York, immediately after this second marriage came the “Reply to Hayne.” The beginning of a new era in his private life coincided with the beginning of a new era in his career as a statesman. After 1830 Mr. Webster was recognized as one of the greatest powers in the nation, and it seemed natural that the presidency should be offered to such a man. His talents, however, were not those of a party leader, and the circumstances under which the Whig party was formed were not such as to place him at its head. The elements of which that party was made up were incongruous, the bond of union between them consisting chiefly of opposition to President Jackson's policy. In the election of 1836 they had not time in which to become welded together, and after the brief triumph of 1840 they soon fell apart again. In 1836 there was no general agreement upon a candidate. The northern Whigs, or National Republicans, supported by the anti-Masons, nominated Gen. William H. Harrison; the southern or “state-rights” Whigs nominated Hugh L. White; the legislature of Massachusetts nominated Mr. Webster, and he received the electoral vote of that state only. Over such an ill-organized opposition Mr. Van Buren easily triumphed. In March, 1837, on his way from Washington to Boston, Mr. Webster stopped in New York and made a great speech at Niblo's garden, in which he reviewed and criticised the policy of the late administration, with especial reference to its violent treatment of the bank. In the course of the speech he used language that was soon proved prophetic by the financial crisis of that year. In the summer he made a journey through the western states. In the next session of congress his most important speeches were those on the sub-treasury bill. The second of these, delivered 12 March, 1838, contained some memorable remarks on the course of Mr. Calhoun, who had now taken sides with the administration. No passage in all his speeches is more graphic than that in which, with playful sarcasm, he imagines Gen. Jackson as coming from his retirement at the Hermitage, walking into the senate-chamber, and looking across “to the seats on the other side.” The whole of that portion of the speech which relates to nullification is extremely powerful. Mr. Calhoun, in his reply, “carried the war into Africa,” and attacked Mr. Webster's record. He was answered, 22 March, by a speech that was a model for such parliamentary retorts. Mr. Webster never sneered at his adversaries, but always rendered them the full meed of personal respect that he would have demanded for himself. He discussed questions on their merits, and was too great to descend to recriminations. His Titanic power owed very little to the spirit of belligerency. Never was there an orator more urbane or more full of Christian magnanimity.

In the summer of 1839 Mr. Webster with his

family visited England, where he was cordially

received and greatly admired. On his return in

December he learned that the Whigs had this time

united upon Gen. Harrison for their candidate in

the hope of turning to their own uses the same

kind of unreflecting popular enthusiasm that had

elected Jackson. The panic of 1837 aided them

still more, and Mr. Webster made skilful use of it

in a long series of campaign speeches, during the

summer of 1840, in Massachusetts, New York,

Pennsylvania, and Virginia. He accepted the office

of secretary of state in President Harrison's

administration, and soon showed himself as able in

diplomacy as in other departments of statesmanship.

There

was a complication

of

difficulties with

Great Britain

which seemed

to be bringing

us to the verge

of war. There

was the

long-standing

dispute about

the northeastern

boundary,

which had

not been adequately defined by the treaty of 1783,

and along with the renewal of this controversy

came up the cases of McLeod and the steamer

“Caroline,” the slave-ship “Creole,” and all the

manifold complications that these cases involved.

The Oregon question, too, was looming in the

background. In disentangling these difficulties

Mr. Webster showed wonderful tact and discretion.

He was fortunately aided by the change of ministry

in England, which transferred the management

of foreign affairs from the hands of Lord

Palmerston to those of Lord Aberdeen. Edward

Everett was then in London, and Mr. Webster

secured his appointment as minister to Great Britain.

In response to this appointment, Lord Ashburton,

whose friendly feeling toward the United States

was known to every one, was sent over on a special

mission to confer with Mr. Webster, and the result

was the Ashburton treaty of 1842, by which an

arbitrary and conventional line was adopted for

the northeastern boundary, while the loss thereby

suffered by the states of Maine and Massachusetts

was to be indemnified by the United States. It

was also agreed that Great Britain and the United

States should each keep its own squadron to watch

the coast of Africa for the suppression of the

slave-trade, and that in this good work each nation

should separately enforce its own laws. This clause

of the treaty was known as the “cruising convention.”

The old grievance of the impressment of

seamen, which had been practically abolished by

the glorious victories of American frigates in the

war of 1812-'15, was now formally ended by Mr.

Webster's declaration to Lord Ashburton that

henceforth American vessels would not submit

themselves to be searched. Henceforth the

enforcement of the so-called “right of search” by a

British ship would be regarded by the United

States as a casus belli. When all the circumstances

are considered, this Ashburton treaty shows that

Mr. Webster's powers as a diplomatist were of the

highest order. In the hands of an ordinary statesman

the affair might easily have ended in a war;

but his management was so dexterous that, as we

now look back upon the negotiation, we find it

hard to realize that there was any real danger.

Perhaps there could be no more conclusive proof

or more satisfactory measure of his really brilliant

and solid success.

While these important negotiations were going on, great changes had come over the political horizon. There had been a quarrel between the northern and southern sections of the Whig party (see Tyler, John), and on 11 Sept., 1841, all the members of President Tyler's cabinet, except Mr. Webster, resigned. It seems to have been believed by many of the Whigs that a unanimous resignation on the part of the cabinet would force President Tyler to resign. The idea came from a misunderstanding of the British custom in similar cases, and it is an incident of great interest to the student of American history; but there was not the slightest chance that it should be realized. Had there been any such chance, Mr. Webster defeated it by staying at his post in order to finish the treaty with Great Britain. The Whigs were inclined to attribute his conduct to unworthy motives, and no sooner had the treaty been signed, 9 Aug., 1842, than the newspapers began calling upon him to resign. The treaty was ratified in the senate by a vote of 39 to 9, but it had still to be adopted by parliament, and much needless excitement was occasioned on both sides of the ocean by the discovery of an old map in Paris, sustaining the British view of the northeastern boundary, and another in London, sustaining the American view. Mr. Webster remained at his post in spite of popular clamor until he knew the treaty to be quite safe. In the hope of driving him from the cabinet, the Whigs in Massachusetts held a convention and declared that President Tyler was no longer a member of their party. On a visit to Boston, Mr. Webster made a noble speech in Faneuil hall, 30 Sept., 1842, in the course of which he declared that he was neither to be coaxed nor driven into an action that in his own judgment was not conducive to the best interests of the country. He knew very well that by such independence he was likely to injure his chances for nomination to the presidency. He knew that a movement in favor of Mr. Clay had begun in Massachusetts, and that his own course was adding greatly to the impetus of that movement. But his patriotism rose superior to all personal considerations. In May, 1843, having seen the treaty firmly established, he resigned the secretaryship and returned to the practice of his profession in Boston. In the canvass of 1844 he supported Mr. Clay in a series of able speeches. On Mr. Choate's resignation, early in 1845, Mr. Webster was re-elected to the senate. The two principal questions of Mr. Polk's administration related to the partition of Oregon and the difficulties that led to war with Mexico. The Democrats declared that we must have the whole of Oregon up to the parallel of 54° 40', although the 49th parallel had already been gested as a compromise-line. In a very able speech at Faneuil hall, Mr. Webster advocated the adoption of this compromise. The speech was widely read in England and on the continent of Europe, and Mr. Webster followed it by a private letter to Mr. Macgregor, of Glasgow, expressing a wish that the British government might see fit to offer the 49th parallel as a boundary-line. The letter was shown to Lord Aberdeen, who adopted the suggestion, and the dispute accordingly ended in the partition of Oregon between the United States and Great Britain. This successful interposition disgusted some Democrats who were really desirous of war with England, and Charles J. Ingersoll, member of congress from Pennsylvania and chairman of the committee on foreign affairs, made a scandalous attack upon Mr. Webster, charging him with a corrupt use of public funds. Mr. Webster replied in his great speech of 6 and 7 April, 1846, in defence of the Ashburton treaty. The speech was a triumphant vindication of his public policy, and in the thorough investigation of details that followed, Mr. Ingersoll's charges were shown to be utterly groundless.

|

During the operations on the Texas frontier, which brought on war with Mexico, Mr. Webster was absent from Washington. In the summer of 1847 he travelled through the southern states, and was everywhere received with much enthusiasm. He opposed the prosecution of the war for the sake of acquiring more territory, because he foresaw that such a policy must speedily lead to a dangerous agitation of the slavery question. The war brought Gen. Zachary Taylor into the foreground as a candidate for the presidency, and some of the Whig managers actually proposed to nominate Mr. Webster as vice-president on the same ticket with Gen. Taylor. He indignantly refused to accept such a proposal; but Mr. Clay's defeat in 1844 had made many Whigs afraid to take him again as a candidate. Mr. Webster was thought to be altogether too independent, and there was a feeling that Gen. Taylor was the most available candidate and the only one who could supplant Mr. Clay. These circumstances led to Taylor's nomination, which Mr. Webster at first declined to support. He disapproved of soldiers as presidents, and characterized the nomination as “one not fit to be made.” At the same time he was far from ready to support Mr. Van Buren and the Free-soil party, yet in his situation some decided action was necessary. Accordingly, in his speech at Marshfield, 1 Sept., 1848, he declared that, as the choice was really between Gen. Taylor and Gen. Cass, he should support the former. It has been contended that in this Mr. Webster made a great mistake, and that his true place in this canvass would have been with the Free-soil party. He had always been opposed to the further extension of slavery; but it is to be borne in mind that he looked with dread upon the rise of an anti-slavery party that should be supported only in the. northern states. Whatever tended to array the north and the south in opposition to each other Mr. Webster wished especially to avoid. The ruling purpose of his life was to do what he. could to prevent the outbreak of a conflict that might end in the disruption of the Union; and it may well have seemed that there was more safety in sustaining the Whig party in electing its candidate by the aid of southern votes than in helping into life a new party that should be purely sectional. At the same time, this cautious policy necessarily involved an amount of concession to southern demands far greater than the rapidly growing anti-slavery sentiment in the northern states would tolerate. No doubt Mr. Webster's policy in 1848 pointed logically toward his last great speech, 7 March, 1850, in which he supported Mr. Clay's elaborate compromises for disposing of the difficulties that had grown out of the vast extension of territory consequent upon the Mexican war. (See Clay, Henry.) This speech aroused intense indignation at the north, and especially in Massachusetts. It was regarded by many people as a deliberate sacrifice of principle to policy. Mr. Webster was accused of truckling to the south in order to obtain southern support for the presidency. Such an accusation seems inconsistent with Mr. Webster's character, and a comprehensive survey of his political career renders it highly improbable. The “Seventh-of-March” speech may have been a political mistake; but one cannot read it to-day, with a clear recollection of what was thought and felt before the civil war, and doubt for a moment the speaker's absolute frankness and sincerity. He supported Mr. Clay's compromises because they seemed to him a conclusive settlement of the slavery question. The whole territory of the United States, as he said, was now covered with compromises, and the future destiny of every part, so far as the legal introduction of slavery was concerned, seemed to be decided. As for the regions to the west of Texas, he believed that slavery was ruled out by natural conditions of soil and climate, so that it was not necessary to protect them by a Wilmot proviso. As for the fugitive-slave law, it was simply a provision for carrying into effect a clause of the constitution, without which that instrument could never have been adopted, and in the frequent infraction of which Mr. Webster saw a serious danger to the continuance of the Union. He therefore accepted the fugitive-slave law as one feature in the proposed system of compromises; but, in accepting it, he offered amendments, which, if they had been adopted, would have gone far toward depriving it of some of its most obnoxious and irritating features. By adopting these measures of compromise. Mr. Webster believed that the extension of slavery would have been given its limit, that the north would, by reason of its free labor, increase in preponderance over the south, and that by and by the institution of slavery, hemmed in and denied further expansion, would die a natural death. That these views were mistaken, the events of the next ten years showed only too plainly, but there is no good reason for doubting their sincerity. There is little doubt, too, that the compromises had their practical value in postponing the inevitable conflict for ten years, during which the relative strength of the north was increasing and a younger generation was growing up less tolerant of slavery and more ready to discard palliatives and achieve a radical cure. So far as Mr. Webster's moral attitude was concerned, although he was not prepared for the bitter hostility that riis speech provoked in many quarters, he must nevertheless have known that it was quite as likely to injure him at the north as to gain support for him in the south, and his resolute adoption of a policy that he regarded as national rather than sectional was really an instance of high moral courage. It was, however, a concession that did violence to his sentiments of humanity, and the pain and uneasiness it occasioned is visible in some of his latest utterances.

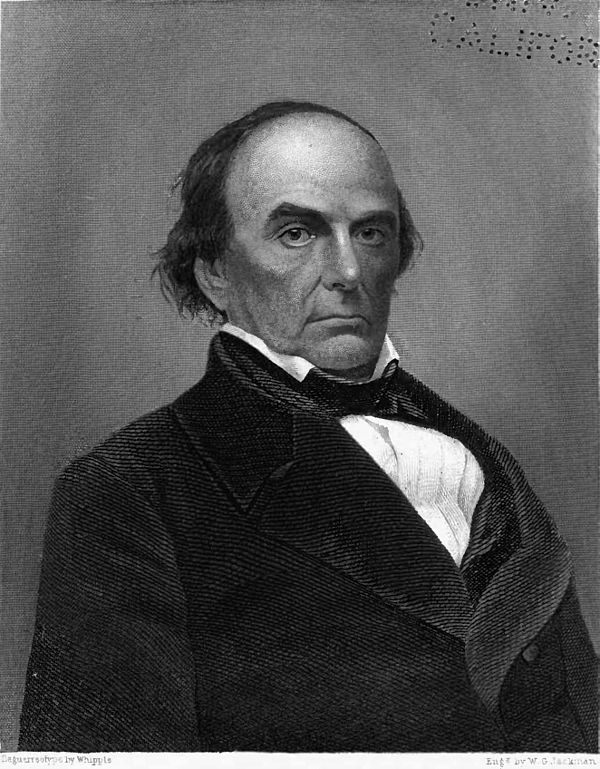

On President Taylor's death, 9 July, 1850, Mr. Webster became President Fillmore's secretary of state. An earnest attempt was made on the part of his friends to secure his nomination for the presidency in 1852; but on the first ballot in the convention he received only 29 votes, while there were 131 for Gen. Scott and 133 for Mr. Fillmore. The efforts of Mr. Webster's adherents succeeded only in giving the nomination to Scott. The result was a grave disappointment to Mr. Webster. He refused to support the nomination, and took no part in the campaign. His health was now rapidly failing. He left Washington, 8 Sept., for the last time, and returned to Marshfield, which he never left again, except on 20 Sept. for a brief call upon his physician in Boston. By his own request there were no public ceremonies at his funeral, which took place very quietly, 29 Sept., at Marshfield. The steel engraving of Webster is from a portrait made about 1840, the vignette from a painting by James B. Longacre, executed in 1833. The other illustrations represent the Bunker Hill monument, his residence and grave at Marshfield, and the imposing statue by Thomas Ball, erected in the Central park, New York. See Webster's “Works,” with biographical sketch by Edward Everett (6 vols., Boston, 1851); “Webster's Private Correspondence,” edited by Fletcher Webster (2 vols.. Boston, 1856); George Ticknor Curtis's “Life of Webster” (2 vols.. New York, 1870); Edwin P. Whipple's “Great Speeches of Webster” (Boston, 1879); and Henry Cabot Lodge's “Webster,” in “American Statesmen Series” (Boston, 1883). — Daniel's son, Fletcher, lawyer, b. in Portsmouth, N. H., 23 July, 1813; d. near Bull Run, Va., 30 Aug., 1862, was graduated at Harvard in 1833, studied law with his father, and was admitted to the bar. He was private secretary to his father during part of the latter's service as secretary of state, secretary of legation in China under Caleb Cushing in 1843, a member of the Massachusetts legislature in 1847, and from 1850 till 1861 surveyor of the port of Boston. He became colonel of the 12th Massachusetts regiment, 26 June, 1861, served in Virginia and Maryland, and was killed at the second battle of Bull Run. Besides editing his father's private correspondence, Col. Webster published an “Oration before the Authorities of the City of Boston, July 4, 1846.”