Archaeological Journal/Volume 3/Notices of New Publications: The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland

Notices of New publications.

The Ecclesiastical Architecture of Ireland, anterior to the Anglo-Norman Invasion; comprising an Essay on the origin and uses of The Round Towers of Ireland, By George Petrie, R.H.A., V.P. R.I.A. Vol. I. 4to. Dublin, 1845. Also re-printed in royal 8vo., 1846.

HE character of this work is already so well established that it is needless to recommend it to the attention of the members of the Institute. The object of the present notice is therefore to make its value and importance better known to those who have not had access to the original work; to examine the data upon which Mr. Petrie has ventured to differ from the opinions received among well informed antiquaries on some particular points in his essay; and to shew the light that has been thrown by his work upon the history of architecture.

HE character of this work is already so well established that it is needless to recommend it to the attention of the members of the Institute. The object of the present notice is therefore to make its value and importance better known to those who have not had access to the original work; to examine the data upon which Mr. Petrie has ventured to differ from the opinions received among well informed antiquaries on some particular points in his essay; and to shew the light that has been thrown by his work upon the history of architecture.

The first hundred pages of Mr. Petrie's work are occupied with an examination of the erroneous theories of previous writers with respect to the origin and uses of the round towers. This examination is conducted with much tact and skill, and exhibits great learning and research. He is completely successful in the task he undertook of demolishing all previous theories, whether of the Danish, or Phœnician, or Eastern, or Pagan uses of the round towers, and he satisfactorily proves that whatever their exact ages may be, they are certainly Christian. To use his own words, he has fully established,

"1. That not even the shadow of an historical authority has been adduced to show that the Irish were acquainted with the art of constructing an arch, or with the use of lime cement, anterior to the introduction of Christianity into the country; and further, that though we have innumerable remains of buildings, of ages antecedent to that period, in no one of them has an arch, or lime cement, been found.

"2. That in no one building in Ireland assigned to pagan times, either by historical evidence or popular tradition, have been found either the form or features usual in the round towers, or characteristics that would indicate the possession of sufficient architectural skill in their builders to construct such edifices.

"3. That, previously to General Vallancey,—a writer remarkable for the daring rashness of his theories, for his looseness in the use of authorities, and for his want of acquaintance with medieval antiquities,—no writer had ever attributed to the round towers any other than a Christian, or, at least, a medieval origin.

"4. And lastly, that the evidences and arguments tendered in support of this theory by Vallancey and his followers,—excepting those of the late Mr. O'Brien and Sir William Betham, which I have not thought deserving of notice,—have been proved to be of no weight or importance.

"In addition to these facts, the four which follow will be proved in the descriptive notices of the ancient churches and towers which will constitute the third part of this inquiry.

"1. That the towers are never found unconnected with ancient ecclesiastical foundations.

"2. That their architectural styles exhibit no features or peculiarities not equally found in the original churches with which they are locally connected, when such remain.

"3. That on several of them Christian emblems are observable; and that others display, in their details, a style of architecture universally acknowledged to belong to Christian times.

"4. That they possess, invariably, architectural features not found in any buildings in Ireland ascertained to be of pagan times.

"For the present, however, I must assume these additional facts as proved, and will proceed to establish the conclusions as to their uses originally stated; namely, I. that they were intended to serve as belfries; and, II. as keeps, or places of strength, in which the sacred utensils, books, relics, and other valuables, were deposited, and into which the ecclesiastics to whom they belonged could retire for security, in cases of sudden predatory attack.

"These uses will, I think, appear obvious to a great extent, from their peculiarities of construction, which it will be proper, in the first place, to describe. These towers, then,—as will be seen from the annexed characteristic illustration, representing the perfect tower on Devenish Island in Lough Erne,—are rotund, cylindrical structures, usually tapering upwards, and varying in height from fifty to perhaps one hundred and fifty feet; and in external circumference, at the base, from forty to sixty feet, or somewhat more. They have usually a circular, projecting base, consisting of one, two, or three steps, or plinths, and are finished at the top with a conical roof of stone, which, frequently, as there is every reason to believe, terminated with a cross formed of a single stone. The wall, towards the base, is never less than three feet in thickness, but is usually more, and occasionally five feet, being always in accordance with the general proportions of the building. In the interior they are divided into stories, varying in number from four to eight, as the height of the tower permitted, and usually about twelve feet in height. These stories are marked either by projecting belts of stone, set-offs or ledges, or holes in the wall to receive joists, on which rested the floors, which were almost always of wood. In the uppermost of these stories the wall is perforated by two, four, five, six, or eight apertures, but most usually four, which sometimes face the cardinal points, and sometimes not. The lowest story, or rather its place, is sometimes composed of solid masonry, and when not so, it has never any aperture to light it. In the second story the wall is usually perforated by the entrance doorway, which is generally from eight to thirty feet from the ground, and only large enough to admit a single person at a time. The intermediate stories are each lighted by a single aperture, placed variously, and usually of very small size, though in several instances, that directly over the doorway is of a size little less than that of the doorway, and would appear to be intended as a second entrance.

"In their masonic construction they present a considerable variety: but the generality of them are built in that kind of careful masonry called spawled rubble, in which small stones, shaped by the hammer, in default of suitable stones at hand, are placed in every interstice of the larger stones. so that very little mortar appears to be intermixed in the body of the wall; and thus the outside of spawled masonry, especially, presents an almost uninterrupted surface of stone, supplementary splinters being carefully inserted in the joints of the undried wall. Such, also, is the style of masonry of the most ancient churches; but it should be added that, in the interior of the walls of both, grouting is abundantly used. In some instances, however, the towers present a surface of ashlar masonry,—but rarely laid in courses perfectly regular,—both externally and internally, though more usually on the exterior only; and, in a few instances, the lower portion of the towers exhibits less of regularity than the upper parts.

"In their architectural features an equal diversity of style is observable; and of these the doorway is the most remarkable. When the tower is of rubble masonry, the doorways seldom present any decorations, and are either quadrangular, and covered with a lintel, of a single stone of great size, or semicircular-headed, either by the construction of a regular arch, or the cutting of a single stone. There are, however, two instances of very richly decorated doorways in towers of this description, namely, those of Kildare and Timahoe. In the more regularly constructed towers the doorways are always arched semicircularly, and are usually ornamented with architraves, or bands, on their external faces. The upper apertures but very rarely present any decorations, and are most usually of a quadrangular form. They are, however, sometimes semicircular-headed, and still oftener present the triangular or straight- sided arch. I should further add, that in the construction of these apertures very frequent examples occur of that kind of masonry, consisting of long and short stones alternately, now generally considered by antiquaries as a characteristic of Saxon architecture in England.

"The preceding description will, I trust, be sufficient to satisfy the reader that the round towers were not ill-adapted to the double purpose of belfries and castles, for which I have to prove they were chiefly designed; and keeping this double purpose in view, it will. I think, satisfactorily account for those peculiarities in their structure, which would be unnecessary if they had been constructed for either purpose alone. For example, if they had been erected to serve the purpose of belfries only, there would be no necessity for making their doorways so small, or placing them at so great a distance from the ground; while, on the other hand, if they had been intended solely for ecclesiastical castles, they need not have been of such slender proportions and great altitude." pp. 353—7.

This is an admirable summary of the whole work, and all that remains is to fill up the skeleton with examples. It is clear that the round towers must not be considered by themselves, but always in connection with the churches to which they are attached.

One more example must suffice to shew this connection.

"This tower, (Clonmacnoise,) as well as the church with which it is connected, is wholly built of ashlar masonry, of a fine sandstone, laid in horizontal courses, and is of unusually small size; its height, including the conical roof, being but fifty-six feet, its circumference thirty-nine feet, and the thickness of its wall, three feet. Its interior exhibits rests for five floors, each story, as usual, being lighted by a small aperture, except the uppermost, which, it is remarkable, has but two openings, one facing the north, and the other the south. These openings are also remarkable for their small size; and, in form, some are rectangular, and others semicircular-headed." pp. 411—12.

This is also the only instance in which the apertures are recessed, and Mr. Petrie observes "that it is a building obviously of much later date than the generality of the round towers, and presents an equally singular peculiarity in the construction of its roof, as compared with those of the other towers, namely, its masonry being of that description called herring-bone, or rather herring-bone ashlar, and the only instance of such construction which these buildings now exhibit." (p. 411.) Yet in another part of the work we find Mr. Petrie contending for the high antiquity of this tower, setting aside the strong evidence which would fix it at the end of the twelfth century, the Registry of Clonmacnoise, and the opinion of Archbishop Usher and Sir James Ware; and endeavouring to prove by tradition that it is some centuries older, although the utmost that the incidental notices he has so ingeniously collected can prove, is that there was a church on this site at an earlier period,—the old and often exploded, but constantly recurring, fallacy, of confounding the date of the original foundation with that of the existing structure; and this appears to be the great blemish of Mr. Petrie's work throughout; he has demolished all his predecessors, but is not content to let the result of his own labours rest on the basis of probability, and a comparison with similar buildings in other parts of Europe of the periods to which he assigns several of these interesting structures. We may follow him safely as a guide to a great extent, but must draw back from some of his conclusions, especially when he endeavours to prove that the chevron and other well known ornaments usually considered as Norman, were in use in Ireland long and long before the conquest of England by the Normans. The evidence which he brings forward on this head is by no means conclusive, or satisfactory. In this particular Mr. Petrie seems not to have escaped from the usual prejudices of his countrymen, in no one instance will the evidence on this subject bear sifting; but as this is the only weak point in the book, it is not necessary to dwell upon it farther, and the examination of each particular instance would occupy more space than our limits will afford.

With this protest we pass on to the more pleasing task of shewing that Mr. Petrie has brought to light a large class of buildings in Ireland of a period more remote than any that are known to exist in England, and has established their date with much research and ingenuity, in a manner which leaves nothing to be desired, and upon evidence which appears quite irresistible. In other cases, where the evidence is of more doubtful character, he states it clearly and candidly, and though he has an evident leaning to one side, generally that which gives the greatest antiquity to the structure in question, he endeavours rather to lead than to drag his readers along with him.

"It must be admitted that the opinion expressed by Sir James Ware, as founded on the authority of St. Bernard's Life of St. Malachy, that the Irish first began to build with stone and mortar in the twelfth century, would, on a casual examination of the question, seem to be of great weight, and extremely difficult to controvert; for it would appear, from ancient authorities of the highest character, that the custom of building both houses and churches with oak timber and wattles was a peculiar characteristic of the Scotic race, who were the ruling people in Ireland from the introduction of Christianity till the Anglo-Norman Invasion in the twelfth century. Thus we have the authority of Venerable Bede that Finian, who had been a monk of the monastery of Iona, on becoming bishop of Lindisfarne, 'built a church for his episcopal see, not of stone, but altogether of sawn wood covered with reeds, after the Scotic [that is, the Irish] manner.'

"' . . . fecit Ecclesiam Episcopali sedi congruam, quam tamen more Scottorum, non de lapide, sed de robore secto, totam composuit atque harundine texit.'"—Beda, Hist. Eccl., lib. iii. c. 25.

"In like manner, in Tirechan's Annotations on the Life of St. Patrick, preserved in the Book of Armagh, a MS. supposed to be of the seventh century, we find it stated, that 'when Patrick went up to the place which is called Foirrgea of the sons of Awley, to divide it among the sons of Awley, he built there a quandrangular church of moist earth, because wood was not near at hand.'"

"'Et ecce Patricius perrexit ad agrum qui dicitur Foirrgea filiorum Amolngid ad dividendum inter filios Amolngid, et fecit ibi æclesiam terrenam de humo quadratam quia non prope erat silva.'"—Fol. 14, b. 2.

"And lastly, in the Life of the virgin St. Monnenna, compiled by Conchubran in the twelfth century, as quoted by Usher, it is similarly stated that she founded a monastery which was made of smooth timber, according to the fashion of the Scotic nations, who were not accustomed to erect stone walls, or get them erected.

"'E lapide enim sacras ædes efficere, tam Scotis quàm Britonibus morem fuisse insolitum, ex Bedâ quoq; didicimus. Indeq; in S. Monennæ monasterio Ecclesiam constructam fuisse notat Conchubranus tabulis de dolatis, juxta morem Scoficarum gentium: eo quòd macerias Scoti non solent facere, nec factas habere.'—Primordla, p. 737.

"I have given these passages in full—and I believe they are all that have been found to sustain the opinions alluded to—in order that the reader may have the whole of the evidences unfavourable to the antiquity of our ecclesiastical remains fairly placed before him; and I confess it does not surprise me that, considering how little attention has hitherto been paid to our existing architectural monuments, the learned in the sister countries should have adopted the conclusion which such evidences should naturally lead to; or even that the learned and judicious Dr. Lanigan, who was anxious to uphold the antiquity of those monuments, should have expressed his adoption of a similar conclusion in the following words:

"'Prior to those of the twelfth century we find very few monuments of ecclesiastical architecture in Ireland. This is not to be wondered at, because the general fashion of the country was to erect their buildings of wood, a fashion, which in great part continues to this day in several parts of Europe. As consequently their churches also were usually built of wood, it cannot be expected that there should be any remains of such churches at present.'"—Eccl. Hist., vol. iv. pp. 391, 392.

"It is by no means my wish to deny that the houses built by the Scotic race in Ireland were visually of wood, or that very many of the churches erected by that people, immediately after their conversion to Christianity, were not of the same perishable material. I have already proved these facts in my Essay on the Ancient Military Architecture of Ireland anterior to the Anglo-Norman Conquest. But I have also shewn, in that Essay, that the earlier colonists in the country, the Firbolg and Tuatha De Danann tribes, which our historians bring hither from Greece at a very remote period, were accustomed to build, not only their fortresses but even their dome-roofed houses and sepulchres, of stone without cement, and in the style now usually called Cyclopean and Pelasgic. I have also shewn that this custom, as applied to their forts and houses, was continued in those parts of Ireland in which those ancient settlers remained, even after the introduction of Christianity, and, as I shall presently shew, was adopted by the Christians in their religious structures." pp. 122—24.

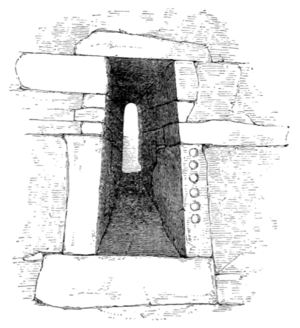

Many examples of these remarkable structures are given in Mr. Petrie's work, one, of which the evidence appears very complete, is "the house of St. Finan Cam, who flourished in the sixth century, and is situated on Church Island in Lough Lee or Curraun Lough, on the boundary of the baronies of Iveragh and Dunkerrin, in the county of Kerry, and four miles to the north of Derrynane Abbey, which derives its name from that saint. This structure, though nearly circular on the outside, is quadrangular on the inside, and measures sixteen feet six inches in length, from north to south, and fifteen feet one inch from east to west, and the wall is seven feet thick at the base, and at present but nine feet nine inches in height; the doorway is on the north side, and measures on the outside four feet three inches in height, and in width two feet nine inches at top, and three feet at bottom. There are three stones forming the covering of this doorway, of which the external one is five feet eight inches in length, one foot four inches in height, and one foot eight inches in breadth; and the internal one is five feet two inches in length, and two feet nine inches in breadth." pp. 127—8.

"In the remote barony of Kerry called Corcaguiny, and particularly in the neighbourhood of Smerwick Harbour, where the remains of stone fortresses and circular stone houses are most numerously spread through the valleys and on the mountains, we meet with several ancient oratories, exhibiting only an imperfect development of the Roman mode of construction, being built of uncemented stones admirably fitted to each other, and their lateral walls converging from the base to their apex in curved lines;—indeed their end walls, though in a much lesser degree, converge also. Another feature in these edifices worthy of notice, as exhibiting a characteristic which they have in common with the pagan monuments, is, that none of them evince an acquaintance with the principle of the arch, and that, except in one instance, that of Gallerus, their doorways are extremely low, as in the pagan forts and houses.

"As an example of these most interesting structures, which, the historian of Kerry truly says, 'may possibly challenge even the round towers as to point of antiquity,' I annex a view of the oratory at Gallerus, the most beautifully constructed and perfectly preserved of those ancient structures now remaining; and views of similar oratories will be found in the succeeding part of this work.

"This oratory, which is wholly built of the green stone of the district, is externally twenty-three feet long by ten broad, and is sixteen feet high on the outside to the apex of the pyramid. The doorway, which is placed, as is usual in all our ancient churches, in its west-end wall, is five feet seven inches high, two feet four inches wide at the base, and one foot nine inches at the top; and the walls are four feet in thickness at the base. It is lighted by a single window in its east side, and each of the gables was terminated by small stone crosses, only the sockets of which now remain.

"That these oratories,—though not, as Dr. Smith supposes, the first edifices of stone that were erected in Ireland,—were the first erected for Christian uses, is, I think, extremely probable; and I am strongly inclined to believe that they may be even more ancient than the period assigned for the conversion of the Irish generally by their great apostle Patrick. I should state, in proof of this antiquity, that adjacent to each of these oratories may be seen the remains of the circular stone houses, which were the habitations of their founders; and, what is of more importance, that their graves are marked by upright pillar-stones, sometimes bearing inscriptions in the Ogham character, as found on monuments presumed to be pagan, and in other instances, as at the oratory of Gallerus, with an inscription in the Græco-Roman or Byzantine character of the fourth or fifth century, of which the annexed is an accurate copy.

This inscription is not perfectly legible in all its letters, but is sufficiently so to preserve the name of the ecclesiastic, viz.

'THE STONE OF COLUM SON OF . . . MEL.'

"It is greatly to be regretted that any part of this inscription should be imperfect, but we have a well-preserved and most interesting example of the whole alphabet of this character on a pillar-stone now used as a gravestone in the church-yard of Kilmalkedar, about a mile distant from the former, and where there are the remains of a similar oratory. Of this inscription I also annex a copy:" p. 131.

Of the doorways, windows, and other details of these buildings we have a copious selection.

"The next example, which I have to submit to the reader, is of somewhat later date, being the doorway of the church of St. Fechin, at Fore, in the county of Westmeath, erected, as we may conclude, within the first half of the seventh century, as the saint died of the memorable plague, which raged in Ireland in the year 664.

"This magnificent doorway, which the late eminent antiquarian traveller, Mr. Edward Dodwell, declared to me, was as perfectly Cyclopean in its character, as any specimen he had seen in Greece, is constructed altogether of six stones, including the lintel, which is about six feet in length, and two in height, the stones being all of the thickness of the wall, which is three feet. This doorway, like that of the Lady's Church at Glendalough, has a plain architrave over it, which is, however, not continued along its sides; and above this, there is a projecting tablet, in the centre of which is sculptured in relief a plain cross within a circle. This cross is thus alluded to in the ancient Life of St. Fechin, translated from the Irish, and published by Colgan in his Acta Sanctorum, at the 22nd January, cap. 23, p. 135.

"'Dum S. Fechinus rediret Fouariam, ibique consisteret, venit ad eum ante fores Ecclesiæ, vbi crux posita est, quidam à talo vsque ad verticem lepra percussus.'

"Though this doorway, like hundreds of the same kind in Ireland, has attracted no attention in modern times, the singularity of its massive structure was a matter of surprise to an intelligent writer of the seventeenth century. Sir Henry Piers, p. 172.

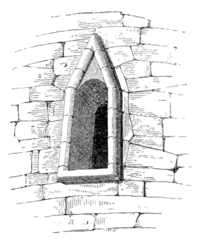

"I have next to speak of the windows. In these features, which are always of a single light, the same simple forms are found, which characterize the doorways, namely, the inclined sides, and the horizontal and semi- circular heads; the horizontal head, however, so common in the doorways, is but of comparatively rare occurrence in the windows; while, on the other hand, the pointed head formed by the meeting of two right lines, which is so rare, if not unknown, in the most ancient doorways, is of very frequent occurrence. I may observe also, that the horizontal-headed window and the triangular-headed one, are usually found in the south wall of the chancel, and very rarely in the east wall, which usually contains a semicircular-headed window, the arch of which is often cut out of a single stone, as in the annexed example in the church of the Trinity, at Glendalough. p. 179.

"A semicircular-headed window in the east end of St. Mac Dara's church, on the island called Cruach Mic Dara, off the coast of Connamara; and a semicircular-headed window, quadrangular on the inside, in the east end of St. Cronan's church, at Termoncronan, in the parish of Carron, barony of Burren, and county of Clare:

"The same mode of construction is observable in the windows of the ancient oratories, which are built without cement, in the neighbourhood of Dingle, in the county of Kerry, as in the east and only window in the oratory at Gallerus, of which an external view has been already given, p. 182.

"As an example of the general appearance of these primitive structures, when of inferior size, I annex an engraving of the very ancient church called Tempull Ceannanach, on Inis Meadhoin, or the Middle Island, of Aran, in the Bay of Galway. This little church,—which would be in perfect preservation if its stone roof remained,—measures on the inside but sixteen feet six inches in length, and twelve feet six inches in breadth; and its walls, which are three feet in thickness, are built in a style quite Cyclopean, the stones being throughout of great size, and one of them not less than eighteen feet in length,—which is the entire external breadth of the church,—and three feet in thickness.

"The ancient churches are not, however, always so wholly unadorned: in many instances they present flat rectangular projections, or pilasters, of plain masonry at all their angles; and these projections are, in some instances, carried up from the perpendicular angles along the faces of the gables to the very apex, as appears in the annexed engraving of St. Mac Dara's church, on the island of Cruach Mhic Dara, off the coast of Connamara:

"This little church is, in its internal measurement, but fifteen feet in length, and eleven feet in breadth; and its walls, which are two feet eight inches in thickness, are built, like those of the church of St. Ceannanach already described, of stones of great size, and its roof of the same material. The circular stone house of this saint, built in the same style but without cement, still remains, but greatly dilapidated: it is an oval of twenty-four feet by eighteen, and the walls are seven feet in thickness." p. 186.

One remarkable peculiarity will be observed in the greater part of the doorways in these ancient structures, they are built after the Egyptian fashion, narrower at the top than at the bottom : this peculiarity of construction Mr. Petrie considers as evidence of the very high antiquity of the structures in which it occurs, and he labours with much ingenuity to prove that the ornaments upon them are of earlier character than the twelfth century, the period to which he evidently feels that they would naturally be assigned. Without entering into this controversy, it may be observed that this peculiarity scarcely amounts to more than one of those provincialisms which we find prevailing in so many other instances, such as the churches near the Rhine, which were long supposed to belong to a very high antiquity, but which M. De Lassus has proved to be of the very end of the twelfth century.

"The opinions which I have thus ventured to express as to the age of the doorway of the round tower of Kidare, and consequently as to the antiquity, in Ireland, of the style of architecture which it exhibits, will, I think, receive additional support from the agreement of many of its ornaments with those seen in the better preserved, if not more beautiful, doorway of the round tower of Timahoe, in the Queen's County,—a doorway which seems to be of cotemporaneous erection, and which, like that of Kildare, exhibits many peculiarities, that I do not recollect to have found in buildings of the Norman times, either in England or Ireland. The general appearance of this doorway will be seen in the above sketch:

"The strongest evidence in favour of the antiquity of this doorway may, however, be drawn from the construction and general style of the tower, as in the fine-jointed character of the ashlar work in the doorway and windows; and still more in the straightsided arches of all the windows, which, with the exception of a small quadrangular one, perfectly agree in style with those of the most ancient churches and round towers in Ireland, and with those of the churches in England now considered as Saxon." p. 235.

Mr. Petrie gives a profusion of illustrations of the details of the church of the monastery at Glendalough, all of which have very much the look of twelfth century work, though he endeavours to prove them much older; yet they correspond so nearly with the details of the church of Cormac, that we cannot understand why the one should be considered some centuries earlier than the other. Neither can we reconcile Mr. Petrie's endeavour to prove the very early date of some of the latest of these structures, with his previous admissions respecting the general custom of the Scotic race to build of wood. The rude buildings of unhewn stone, and those of Cyclopean masonry may belong to any period, but fine-jointed masonry was not used in England before the twelfth century, and so far from this being evidence in favour of their antiquity, it is, so far as it goes, the very reverse.

"The next example, which I have to adduce, is a church of probably somewhat later date than that of Freshford, and whose age is definitely fixed by the most satisfactory historical evidence. It is the beautiful and well-known stone-roofed church on the rock of Cashel, called Cormac's Chapel, one of the most curious and perfect churches in the Norman style in the British empire. The erection of this church is popularly but erroneously ascribed to the celebrated king-bishop Cormac Mac Cullenan, who was killed in the battle of Bealach Mughna, in the year 908; and it is remarkable that this tradition has been received as true by several antiquaries, whose acquaintance with Anglo-Norman architecture should have led them to a different conclusion. Dr. Ledwich, indeed, who sees nothing Danish in the architecture of this church, supposes it to have been erected in the tenth or beginning of the eleventh century, by some of Cormac's successors in Cashel; but he adds, that it was 'prior to the introduction of the Norman and Gothic styles, for in every respect it is purely Saxon.' Dr. Milner, from whose reputation as a writer on architectural antiquities, we might expect a sounder opinion, declares that 'the present cathedral bears intrinsic marks of the age assigned to its erection, namely, the twelfth; as does Cormac's church, now called Cormac's hall, of the tenth.' —Milner's Letters, p. 131. And lastly, Mr. Brewer, somewhat more cautiously indeed, expresses a similar opinion of the age of this building; 'This edifice is said to have been erected in the tenth century; and from its architectural character few will be inclined to call in question its pretension to so high a date of antiquity.'"—Beauties of Ireland, vol. i., Introduction, p. cxiii.

"A reference, however, to the authentic Irish Annals would have shown those gentlemen that such opinions were wholly erroneous, and that this church did not owe its erection to the celebrated Cormac Mac Cullenan, who flourished in the tenth century, but to a later Cormac, in the twelfth, namely, Cormac Mac Carthy, who was also king of Minister, and of the same tribe with the former. In the Munster Annals, or, as they are generally called, the Annals of Innisfallen, the foundation of this church is recorded." p. 283.

Its consecration in 1134 is also mentioned in this and other cotemporary records.

"The north doorway, which was obviously the grand entrance, is of greater size, and is considerably richer in its decorations. It is ornamented on each side with five separate columns and a double column, supporting concentric and receding arch-mouldings, and has a richly decorated pediment over its external arch. The basso relievo on the lintel of this doorway represents a helmeted centaur, shooting with an arrow at a lion, which appears to tear some smaller animal beneath its feet." P. 290.

The peculiar kind of double base which occurs in this chapel is found also in several of these Irish buildings, and may be regarded as another provincialism.

The two following illustrations will serve as examples of the most peculiar of the windows, the first representing one of the small round windows at the east end of the croft over the chancel of Cormac's church; and the second, one of the windows in the round tower of Timahoe.

Another very interesting feature in Mr. Petrie's valuable work consists of the number of examples with which he has furnished us of early tombstones, sometimes with inscriptions only, of which two specimens have already been given; others ornamented with crosses, and with the interlaced work usually called the Runic knot, which Mr. Petrie considers to have been in use in Ireland long anterior to the irruption of the Danes. These ornaments Mr. Petrie supposes to have been most used "during the ninth and tenth centuries, after which I have seen no example of it on such monuments." He gives examples also of several other figures of similar character, though not exactly the same, one of the most interesting of which is "the tombstone of the celebrated Suibine Mac Maelhumai, one of the three Irishmen who visited Alfred the Great in the year 891, and whose death is recorded in the Saxon Chronicle and by Florence of Worcester at the year 892," and in the Irish annals about the same period.

We cannot conclude this notice of Mr. Petrie's very valuable work without congratulating him that this labour of his life has not been in vain, that he has rendered good service to his country, and contributed an interesting chapter to the general history of architecture. We take this opportunity also of thanking him for the use of the woodcuts he has kindly lent us for this article.