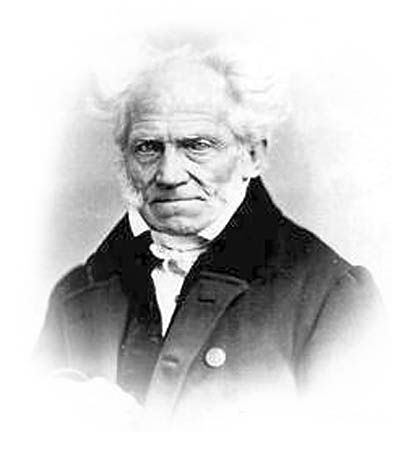

Arthur Schopenhauer, his Life and Philosophy

Born February 22nd 1788,

Died September 21st 1860.

Preface

[edit]NEARLY a quarter of a century has elapsed since the name of ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER was first pronounced in England.[1] This country may claim to have given the signal for the recognition of a thinker not at the time widely known or eminently honoured in his native land; and although the subsequent expansion of his fame and influence has been principally conspicuous in Germany, indications have not been wanting of a steady growth of curiosity and interest respecting him here. Allusions to him in English periodical literature have of late been frequent, assuming an acquaintance with his philosophy on the reader's part which the latter, it may be feared, does not often possess. The time thus seems to have arrived for such an account of the man and the author as may effect for the general reader what M. Ribot's able French précis has already accomplished for the student of mental science, and may prepare the way for the translation of Schopenhauer's capital treatise, understood to be contemplated by an accomplished German scholar now resident among us.

The little volume which owes its existence to these considerations can advance no lofty pretensions either from the biographical or the critical point of view. No new biographical material of importance can be offered now, and there is every reason to believe that none such exists. We must accordingly depend in the main upon the concise memoir by Gwinner—a model of condensation, good taste, and graphic power—supplemented by the heterogeneous and injudicious, yet in many respects invaluable, mass of detail put forth by the philosopher's immediate disciples, Lindner and Frauenstädt. Relying on these sources of information, we have endeavoured to portray for English readers one of the most original and picturesque intellectual figures of our time; with obvious analogies to Johnson, Rousseau, and Byron, nor yielding in interest to any of them, yet a man of unique mould; a cosmopolitan, moreover, exempt from local and national trammels whose mind was formed to be the common possession of his race. The portrait—should the execution have in any degree corresponded with the intention—will, we are convinced, be valued by all who prefer sterling humanity to affectation, who know how to esteem a genuine man. By many it will be deemed unattractive, by some perhaps even forbidding. We shall not be discouraged by cavils grounded upon the fallacy of estimating every man by a uniform conventional standard, without reference to the special mission appointed him in the world. Il faut que chacun ait les défauts de ses qualités. Wordsworth's imperturbable egotism, for example, is even more offensive, because less frankly human, than the boisterous arrogance of Schopenhauer. No one, nevertheless, makes this a crime in Wordsworth, it being universally recognised that he needed all his self-complacency to withstand public contumely; that to wish him other than he was would be to wish that England had never possessed a Wordsworth. Schopenhauer needed even more the steeling armour of self-esteem and scorn, inasmuch as the neglect which exasperated him was more general and more protracted, and arose not, as in Wordsworth's case, from the obtuseness of critics, but from the conspiracy of a coterie. The neglected poet or artist, moreover, has the resource of production; resentment begets new effort, affording an outlet for the pent-up wrath which might otherwise have taken shape as a scandal or a crime, but which now appears transfigured into forms of beauty. The capital labour of Schopenhauer's life, on the other hand, admitted of no repetition; and when it seemed to be dishonoured, the author could but sit brooding over his mortification with a bitterness which, after all, never perverted his intellectual conscience, disgusted him with the seemingly unprofitable pursuit of truth, or impaired his loyalty to the few whom he recognised as worthy of his reverence.

It may still be asked whether Schopenhauer's life-work will really bear comparison with his who brought English poetry back to Nature? If publishing a translation of his writings, we should simply refer the inquirer to the works themselves; but we are painfully aware that no such reference can be confidently made to an abstract whose manifold imperfections are only to be palliated by a necessity and an impossibility the necessity for popular treatment in a volume designed for general readers, the impossibility of exhibiting within our limits the multitudinous aspects of what Schopenhauer himself calls his hundred-gated system. Aware of these inevitable shortcomings, we have striven to let him speak as far as possible for himself—with the result, we trust, of establishing for him an incontestable claim to two immense services, wholly independent of the judgment which may be passed upon the peculiarities of his doctrine. By his lucid and attractive treatment he has made speculative philosophy acceptable to the man of culture and accessible to the mass; by his passion for the concrete, and aptitude for dealing with things as well as thoughts, he has set the pregnant example of testing speculation by science. He will captivate one order of minds by his clear decisive tone as one having authority; another by his profound affinity to the devoutest schools of mysticism, startling as this must appear to those unable to conceive of religion unassociated with some positive creed. Perhaps, however, his most interesting aspect is his character as a representative of the Indian intellect—a European Buddhist. The study of Indian wisdom, conducting by another path to conclusions entirely in harmony with the results of natural science, is destined to affect, and is affecting, the European mind in a degree not inferior to the modification accomplished by the renaissance of Hellenic philosophy; but the process is retarded by the national peculiarities of the Indian sages, and the difficulty of naturalising them in Europe. It is, therefore, much to possess a writer like Arthur Schopenhauer, capable of imparting Western form to Eastern ideas, or rather to ideas once solely Eastern; but which, like seeds wafted by the winds, have wandered far from their birthplace to germinate anew in the brain of Europe. Schopenhauer will for ever stand prominent among those who have helped forward the conception of the Universe as Unity, and even if the peculiar form in which he embodied it fails to obtain currency as the most convenient and correct, it will none the less surely rank among the most impressive and sublime.

CHAPTER I - HIS EARLY YEARS

[edit]IN the cemetery of Frankfort-on-the-Main, is a gravestone of black Belgian granite, half hidden by evergreen shrubs. It bears the inscription : 'Arthur Schopenhauer:' no more; neither date nor epitaph. The great man who lies buried here had himself ordained this. He desired no fulsome inscriptions on his tomb : he wished to be recorded in his works, and when his friend Dr. Gwinner once asked where he desired to be buried, he replied, 'No matter where; posterity will find me.'

And posterity is beginning to find him at last, though it has taken it a long while; and into no civilised country has this great man's fame penetrated later than to England. True, his name and philosophy are not unknown to a select few ; as witness the able article published as long ago as 1853 in the 'Westminster Review,' when the recluse of whom it treated was still living. This essay was the first and is still by far the most adequate notice of the modern Buddhist that has appeared in this country. To this day, Arthur Schopenhauer's name conveys no distinct impression even to educated readers. It is mostly pronounced in disparagement of his philosophy, and dismissed with the contemptuous epithet, 'Nihilist,' by persons who have never read a line of his writings, or given his mode of thought an hour's consideration.

They know possibly that he was a great pessimist, that "'tis better not to be" may be deemed the key-note of his speculations. They leave out of all regard that these tenets, be they congenial to them or no, are based on a great mind's life-thoughts and correspond in essentials with those held by 300 millions of the human race.

Yet notwithstanding all this, after long years of neglect and contempt, he is forcing the world to consider him. Speculations that continue to increase in respect and influence cannot be dismissed with a sneer. Even David Strauss, the optimist par excellence, pays Schopenhauer a grateful tribute in his last work, 'The New Faith and the Old.' As a rule, he remarks, optimism takes things too easily, and for this reason Schopenhauer's references to the colossal part sorrow and evil play in the world are quite in their right place as a counterbalance, though 'every true philosophy is necessarily optimistic, as otherwise she hews down the branch on which she herself is sitting.' An apter and terser illustration is hardly needed to stigmatise such aberrations of thought. Aberrations, however, of such mighty influence and so needful to the complete development of all phases of humanity, that it is imperative upon all who study the history of their own time to know something of this philosopher's mode of thought. The more so as his influence on politics, literature, sociology and art can no longer be contested. Most modern musicians are great admirers of Schopenhauer, especially the followers of Wagner ; some of whom go so far as to say that in order truly to understand the 'music of the future,' it is needful to have begun with his philosophy.

The history of this man, to whom recognition came so late, is not remarkably eventful. It is little else than the record of his thoughts and his works. He had nevertheless seen more of practical life than many a thinker who evolves a system out of his internal consciousness, shut up within the four walls of his study, ignorant of mankind, their needs, and the adaptability of his speculations for their use. Not unjustly does the 'Revue Contemporaine ' say of Schopenhauer, Ce n'est pas un philosophe comme les autres, c'est un philosophe qui a vu le monde.

Arthur Schopenhauer was born at Danzig, on the 22nd of February, 1788. His family were of Dutch extraction, but had long settled in this ancient Reichstadt, which at his birth still maintained its Hanseatic privileges. Schopenhauer attached great importance to hereditary characteristics, regarding them among the prime factors of life. Without touching upon this contested principle, it would not be just to leave his genealogy disregarded in his biography, more especially as he was in a measure a living illustration of his theory. The Schopenhauers, so far back as we can trace them, appear to have been men of powerful character. In the days of Arthur's great-grandfather Andreas, they were already rich and influential citizens, so that when Peter the Great and the Empress Catherine visited Danzig, his house was selected to lodge the Imperial guests. The story of this visit has been preserved in the memoirs of Johanna Schopenhauer, the philosopher's mother, and is characteristic of the ancestor's prompt resolution and practical good sense. She gives it as told by a centenarian family retainer, who lived to dandle the infant Arthur in his arms.

When the Czar and his consort were shown the house, they went all over it to choose their bedroom. Their choice fell upon a room in which there was neither stove nor fireplace. It was winter, and the difficulty how to heat the room arose, for the cold was bitter. Everyone was at their wits' end, till old Herr Schopenhauer came to their aid. He ordered several barrels of fine brandy to be brought from the cellar; these he emptied over the tiled floor, closed up the room carefully, and set the spirit ablaze. The Czar looked with delight at the flaming mass seething around his feet. Meanwhile precautions were taken to hinder the fire from spreading. When all was burnt out, the Imperial pair laid themselves to rest in the hot steamy air, and awoke next morning feeling neither headache nor discomfort, ready to extol their host and his hospitality in terms as glowing as his brandy.

Andreas' son, Johann Friedrich, greatly enlarged the business, and added to the wealth and importance of the family. In later years he retired, and ended his days in a stately mansion near Danzig, which, until its demolition, bore the Schopenhauer name. His wife was also sprung from a good lineage. With advancing age she grew imbecile ; she had borne her husband an idiotic son, and perhaps contributed the hypochondriacal element so traceable in the powerful-minded grandson and in his father, her youngest son, Heinrich Floris. He was born in 1747, and was early sent out into the world to gain knowledge and practical experience. For many years he lived in France and England. In France he served as clerk in the firm of Bethmann, merchants of Bordeaux. The admirable chief of that house won his whole respect. So greatly was he impressed by his conduct in business and family affairs, that in after years, when desirous to emphasise a command, he would add as final argument: 'Monsieur Bethmann acted thus.' He read the French authors of his century with intelligent interest, and above all he was partial to Voltaire. In the working of the English constitution he took a lively interest, and was so pleased with family life in this country that he seriously contemplated making it his home. This love for England and English ways found expression in his country seat at Oliva, near Danzig, which he furnished after the English manner and with English comforts. His garden, too, was laid out in the English style. He daily read an English and French newspaper, and encouraged his son from early boyhood to read the 'Times,' from which, he remarked, 'one could learn everything.' These literary tendencies were undoubtedly inherited by Arthur, who preferred foreign philosophers to those of his country, and was never weary of contrasting Voltaire, Helvetius, Locke, and Hume, with Leibnitz, Fichte, Schelling, and Hegel, commending the former as the only worthy precursors of Kant. He, too, up to his death daily read the 'Times.' Until the German papers began to occupy themselves about him, he rarely condescended to occupy himself with them, a peculiarity less to be condemned on account of their actual inferiority until a comparatively recent period.

Notwithstanding his love for England, Heinrich Schopenhauer returned to his native city, where he entered the business and inherited the bulk of the family property. By this time his character was fully formed. His rectitude, candour, and uncompromising love of truth were remarkable, and won the esteem of his fellow citizens. Fierce, even passionate in his views and prejudices, he did not withal lack the balance and deliberation usually possessed by less excitable natures. The oppressions and iniquities perpetrated by the Prussians against his native city aroused the full vigour of his hate. At the same time he never withheld from the Great Frederick his just meed of praise. Early in life he might indeed, had he wished, have taken office under this monarch. For on his return from his travels he happened to be among the spectators of a review held at Potsdam. The Great Frederick had an eagle eye, and always marked an unusual appearance in a crowd. The elegance of Schopenhauer's dress, his foreign carriage and independent air, attracted the sovereign's notice. The following day he summoned the young man to his cabinet; the interview lasted two hours, during which the King begged, almost commanded him to settle in Prussia. He held out every inducement, promised to exert every influence on his behalf. But it was in vain. The stern republican would not accept patronage from the oppressor of his native city. He never swerved from the family device : Point de bonheur sans liberté; and Frederick was reluctantly obliged to let him depart. He could not forget him : by a cabinet order he assured to Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer and his descendants important privileges, of which, however, they appear never to have availed themselves. This trait alone would serve to prove that Arthur Schopenhauer's father was no ordinary man. Another recorded incident confirms this impression.

After the second partition of Poland the Hanseatic republic of Danzig was destined by Frederick the Great to become his prey. In order to cut off supplies from the landside, the place was blockaded by Prussian troops. The general in command was quartered with Johann Schopenhauer, then living in retirement at his country seat. He showed such generous hospitality to his unwelcome guests that the general desired in some manner to evince his gratitude. He had heard that the old man's son, Heinrich, who lived within the walls, owned horses to which he was so attached that his fondness for them had become proverbial. Forage was growing scarce, and the general offered to allow food for Heinrich's horses to enter. This roused the stern patrician's ire. Why should he be distinguished from among his countrymen? Why should he be deemed willing to receive favours from the hated Prussians? He wrote in reply that he thanked the general for his goodwill; his stables were as yet amply provided, and when the stock was exhausted he should cause his horses to be killed.

It might be supposed that a man who so little conformed to conventionalities, and opposed inflexible prejudice to palpable advantage, would scarcely make a good man of business, above all, a good merchant, perhaps next to a lawyer's, the most trimming and time-serving pursuit. Yet the contrary was the case. Heinrich Schopenhauer conducted his business in a manner that won him all respect and admiration. It was not until he was eight and thirty that he contemplated marriage. His choice fell upon Johanna Henriette Trosiener, a pretty girl of eighteen, whose father was member of the Danzig Senate, and though not wealthy, was counted among the city's patricians. He too had travelled and acquired, like his son-in-law, the cosmopolitan culture uncommon in those days. Cheerful and lively by temperament, these qualities were occasionally overshadowed by unrestrained outbursts of passion so violent that people shunned association with him for very fear. According to the testimony of his daughter, these irruptions of senseless fury seized him quite suddenly, often for the most trivial cause. Fortunately his anger was allayed as rapidly as it arose, but while the attack was upon him even the cat and dog would run away in terror. His wife only could mollify him somewhat.

'It needs but a few strokes to recall the picture of my dear gentle mother, Elizabeth, née Lehmann,' says Johanna Schopenhauer ; 'she had a small dainty figure, with the prettiest hands and feet, a pair of large very light blue eyes, a very white fine skin, and long silky light brown hair. So much for her outward appearance. Her physique was not adapted to make her the robust housekeeper at that time in fashion; with regard to what is demanded nowadays of women, her education had been no less neglected than that of her contemporaries. She could play a few polonaises and mazurkas, accompany herself to a few songs, and read and write sufficiently well for household requirements: that was pretty well all she had been taught. But common sense, natural ability, and the quick power of conception common to women, indemnified her for these deficiencies.'

Such were the parents of the young girl, who on the verge of womanhood was united to a man twenty years her senior. Of her youth we have records from her own pen, as she intended writing her Memoirs, which would have proved interesting, not only with regard to her son, but because she lived on terms of friendly intimacy with the famous men and women of her day. Unfortunately she was only able to bring them down to the year 1789, and as she was born in 1766, they embrace the least generally interesting period of her life. They present, however, a good idea of society in those troublous times. Johanna was the eldest daughter of her parents; she inherited her mother's dainty proportions, light brown hair and clear blue eyes. In youth her figure was unusually attractive and mignonne ; later in life she became corpulent, which, together with a malformation of the hip, detracted from the charm of her exterior. Her countenance was pleasant, but not beautiful ; till her death she preserved a certain grace in carriage and conversation which everywhere attracted attention. She was very popular, and was fond of social gatherings. Some people thought her haughty, which she was not, but she maintained a certain reserve in her demeanour towards strangers, and was besides fully aware of all her advantages, mental and physical.

This is an account of her marriage in her own words. 'Before I had completed my nineteenth year, a brilliant future was opened out to me by this marriage, more brilliant than I was justified in anticipating, but that these considerations had no weight in my youthful mind upon my final decision will be readily believed. I thought I had done with life, a delusion to which one so easily and willingly gives way in early youth upon the first painful experience. I knew I had cause to be proud of belonging to this man, and I was proud. At the same time I as little feigned ardent love for him, as he demanded it from me.'

Her education had been as incomplete as her mother's, but constant communion with a man of Heinrich Schopenhauer's calibre, united to good natural ability, soon developed her intellectual growth. His house, alone, was an education. It was elegantly furnished so as to foster her sense of refinement; the walls were hung with engravings after the old masters, busts and excellent casts of antique statues ornamented the rooms ; the library was stocked with the best French, German, and English authors. An English clergyman attached to the colony at Danzig, Dr. Jameson, had been her friend and tutor from childhood. Under his guidance she read with judicious care and understanding, so that thanks to his aid and that of her husband, combined with the fruitful soil she herself offered for these endeavours, her mental development was rapid.

The honeymoon of this pair was spent at their country seat of Oliva. They had hardly been married before Heinrich was seized with one of his eager longings to travel. The young wife shared his passion, and they set out upon a long journey. Berlin and Hanover were first visited ; from thence they went to Pyrmont, even then a popular watering place. Here they became acquainted with the statesman Justus Möser, not unjustly entitled the Franklin of Germany. After this they proceeded to Frankfort, with which Johanna was especially delighted, little dreaming that it would become the home of her unborn son, whose name was destined to add another glory to that ancient city.

'I felt as if a draught of native air greeted me in Frankfort,' she says. ' Everything recalled Danzig to me with its busy independent life.'

Belgium was next traversed, then the pair visited Paris, and finally crossed to England. It was the father's wish that his son—for he had determined on the sex—should be born in England, in order that he might enjoy all the rights of English citizenship; and with great reluctance he relinquished his purpose, necessitated by his wife's precarious state of health. The journey fell in the depth of winter, and was attended with hardships of which the present generation can form no idea. It was, however, safely accomplished. On the 22nd of February, 1788, the great pessimist first saw the light of a world he deemed so wretched. The house in which he was born still stands, though greatly altered. It is No. 117, Heiligengeiststrasse, in Danzig.

An anecdote of his birthday has been preserved. His father, it appears, was distinguished by intellectual, rather than personal attractions. He was short and clumsily made, his broad face was lighted by prominent eyes, only redeemed from ugliness by their intelligence, his nose was stumpy and upturned, his mouth large and wide. From early youth too he had been deaf. When, on the afternoon of the 22nd of February, he entered his counting-house, and laconically announced to the assembled clerks : 'A son,' the merry book-keeper, relying upon his principal's deafness, exclaimed, to the general amusement : 'If he is like his papa he will be a pretty baboon.' His prophecy was tolerably fulfilled; excepting that Arthur boasted a splendid forehead and penetrating light blue eyes, he resembled his father in build of face and figure.

The child was baptised on the third of March, in the Marienkirche, one of the finest old churches of the Baltic regions. He was called Arthur, because the name remains the same in all European languages, a circumstance regarded as advantageous to a merchant; for to that career the nine-days'-old child was already destined by his circumspect father.

Of the first few years of his life we know nothing. His infancy was contemporaneous with the French Revolution, a political event in which his parents took the liveliest interest, and which naturally aroused all his father's keen republicanism. In 1793 occurred the blockade of Danzig; it was then the incident regarding the horses took place. Heinrich Schopenhauer was firmly resolved to forsake his native city in case of its subjugation by the Prussians ; never would he consent to live under their detested rule. He would rather sacrifice home and fortune. When Danzig's fate was decided, in March, 1793, he did not hesitate one moment to put his resolve into execution. Within twenty-four hours of the entry of the Prussian troops, when he saw that all hope was lost, he, his wife, and little five-year-old son, fled to Swedish Pomerania. Thence they made their way to Hamburg, a sister Hanseatic town, which retained its old freedom and privileges, and was therefore a congenial home for the voluntary exiles. This uncompromising patriotism cost Heinrich Schopenhauer more than a tenth of his fortune, so highly was he taxed for leaving. But he heeded nothing save his rectitude and his principles, qualities his son inherited. His fearless love of truth and honest utterance of his opinion were as marked as his father's.

The family now established their domicile in Hamburg. They were kindly received by the best families, and a new pleasant life opened in place of that left behind. Whether because too old to be transplanted, or from other causes, Heinrich Schopenhauer had not long removed to Hamburg ere he was seized with an almost morbid desire to travel. His wife's joyous temperament, her savoir faire, her perfect mastery of foreign languages, and the ease with which she formed new acquaintances, made her a desirable travelling companion. During the twelve years of their residence at Hamburg many longer and shorter journeys were undertaken, besides which Johanna visited her own people every four years. To Danzig her husband did not accompany her ; he never would re-enter the city. Thus the restlessness engendered by her ill-assorted union found vent in excitement and recreation.

Arthur always accompanied his parents. The education he thus gained was an additional inducement for these trips, and one his father held as by no means least important. Above all, he was anxious his son should have cosmopolitan training, see everything, judge with his own eyes, and be free from those prejudices that too fatally doom 'home-keeping youths' to 'homely wits.' Arthur ever expressed himself thankful for this inestimable advantage ; it exercised great influence upon his life, his character, and his philosophy. True, this nomad existence interfered with the even course of a school education, and hindered the systematic acquirement of ordinary branches of knowledge ; but this was in great measure compensated by the open intelligence it fostered, and entirely redeemed when the youth applied himself strenuously to repair these shortcomings. On the other hand, travel brought him into contact at an early age with some of the best minds of the time. As a child he was acquainted with many celebrities, such as Baroness Staël, Klopstock, Keimarus, Madame Chevalier, Nelson, and Lady Hamilton.

Once, about his nineteenth year, when he found himself deficient in general information in comparison with other youths, he was inclined to regret his abnormal boyhood. The feeling passed never to return. His clear intelligence recognised that the course his life had taken had not been the consequence of chance, but needful to his complete development. For in early youth, when the mind is most prone to receive impressions, and stretches its feelers in all directions, he was made acquainted with actual facts and realities, instead of living in a world of dead letters and bygone tales, like most youths who receive an academic education. To this he attributed much of the freshness and originality of his style : he had learnt, in practical intercourse with men and the world, not to rest satisfied with the mere sound of words, or to take them for the thing itself.

In Arthur's ninth year, his parents undertook a journey through France. On its conclusion they left the boy behind them at Havre with a M. Gregoire, a business friend. Here he remained two years, and was educated together with M. Gregoire's son. His father's object was that Arthur should thoroughly master the French language, an object so completely realized that when he came back to Hamburg it was found he had forgotten his native tongue, and was forced to learn it again like a foreigner. Arthur frequently recalled these two years spent in France as the happiest of his boyhood.

When he had once more accustomed himself to the sound of German, he was sent to school. Here his instruction was entirely conducted with a view to the requirements of the future merchant, and the classics were therefore almost, if not wholly, disregarded. It was soon after that he evinced a decided bent towards the study of philosophy. He entreated his father to grant him the happiness of a collegiate education, a request that met with stern refusal. Heinrich Floris had determined that his son should be a merchant, and old Schopenhauer was not accustomed to be baulked. As time went on, and he saw this yearning was no passing fancy, he condescended to give it more serious consideration, especially as the testimony of the masters endorsed Arthur's prayers. He almost yielded; but the thought of the poverty too often attendant on a votary of the muses, was so repugnant to the life-plans he had formed for his only son, that he determined on a last resort to divert the boy from his purpose. He took refuge in stratagem to effect what he was too just to accomplish by force. He brought the lad's desires into conflict by playing off his love of travelling, and his eagerness to visit his dear friend young Gregoire, against his longing to study philosophy. He put this alternative : either to enter a high school, or to accompany his parents upon a journey of some years' duration, planned to embrace France, England, and Switzerland. If he chose the latter, he was to renounce all thought of an academical career, and to enter business on returning to Hamburg.

It was a hard condition to impose on a boy of fifteen, but the plot had been well laid. The lad could not withstand the inducement; he decided in favour of travel, and turned his back upon learning, as he deemed, for ever.

Of this journey Johanna Schopenhauer wrote a lively account, culling her materials from the copious diary she kept. Her son, too, was encouraged to keep a journal, in order to stimulate accurate observation. The tour included Belgium, France, Switzerland, Germany, and England, and lasted over two years. While his parents made a trip to the north of Britain, Arthur was left at a school in Wimbledon. It was kept by a clergyman, and the boy appears to have been greatly plagued by his master's orthodox theology. It was then doubtless that he laid the foundation for the fierce hatred of English bigotry, derided in his works. Here too he gained his accurate knowledge of the language and literature, with which his school-time was chiefly occupied. His recreations were gymnastics and flute playing.

When the family visited Switzerland, Arthur was overwhelmed with the majesty of the Alps. He could not satiate his gaze with their beauty, and when his parents desired to go further, he entreated to be left at Chamounix, that he might still longer enjoy this glorious sight. Mont Blanc, above all, was the Alp to which he gave his whole heart ; and those who knew him in later life say that he never, even then, could speak of that mountain without a certain tone of sadness and yearning. He touches on this in 'Die Welt als Wille und Vorstellung':

'The sad disposition so often remarked in highly gifted men, has its emblem in this mountain with its cloud-capped summit. But when at time, perchance at dawn, the veil of mist is torn asunder, and the peak, glowing with the sun's reflection, looks down on Chamounix from its celestial height above the clouds, it is a spectacle which stirs every soul to its inmost depths. Thus the most melancholy genius will at times show signs of a peculiar cheerfulness of disposition, which springs from the complete objectiveness of his intellect, and is possible only to him. It hovers like a halo about his noble forehead : in tristitia hilaris, in hilaritate tristis.'

In the autumn of this year (1804) Arthur went to Danzig to receive confirmation in the same venerable Marienkirche that had witnessed his baptism. With the new year he entered a merchant's office, true to his promise. It was hateful to him, but he tried to resign himself. He honoured and respected his father, and held his wish to be law.

A very few months after he had the misfortune to lose this parent, who fell from an attic window into the canal. It had always been his custom to inspect everything in person, and that would sufficiently account for his presence in this part of his warehouse. Report, however, spread that Heinrich Schopenhauer had committed suicide on account of fancied pecuniary loss. He had in truth suffered lately from attacks of over- anxiety, which were thus interpreted as signs of mental derangement. His increased deafness may have helped to foster his violent attacks of passionate anger, which certainly broke out more frequently during the last months of his life. These circumstances combined lent an air of credibility to a rumour often used in after years as a cruel weapon against his son.

Arthur never ceased to reverence his father's memory. An instance of this respect is observable in his remark regarding the mercantile profession. 'Merchants are the only honest class of men : they avow openly that money-making is their object, while others pursue the same end, hiding it hypocritically under cover of an ideal vocation.'

The collected edition of his works was intended to be prefaced by a splendid memorial of his filial gratitude. For some cause this preface was omitted. It deserves quotation as throwing an agreeable light upon a man whom we shall not always find so lovable.

'Noble, beneficent spirit! to whom I owe all that I am, your protecting care has sheltered and guided me not only through helpless childhood and thoughtless youth, but in manhood and up to the present day. When bringing a son such as I am into the world, you made it possible for him to exist and to develop his individuality in a world like this. Without your protection, I should have perished an hundred times over. A decided bias, which made only one occupation congenial, was too deeply rooted in my very being for me to do violence to my nature, and force myself, careless of existence, at best to devote my intellect merely to the preservation of my person ; my sole aim in life how to procure my daily bread. You seem to have understood this ; to have known beforehand that I should hardly be qualified to till the ground, or to win my livelihood by devoting my energies to any mechanical craft. You must have foreseen that your son, oh proud republican! would not endure to crouch before ministers and councillors, Maecenases and their satellites, in company with mediocrity and servility, in order to beg ignobly for bitterly earned bread; that he could not bring himself to flatter puffed-up insignificance, or join the sycophantic throng of charlatans and bunglers ; but that, as your son, he would think, with the Voltaire whom you honoured, "Nous n'avons que deux jours a vivre : il ne vaut pas la peine de les passer a ramper devant les joquins meprisables."

'Therefore I dedicate my work to you, and call after you to your grave the thanks I owe to you and to none other. "Nam Caesar nullus nobis haec otia fecit."

'That I was able to cultivate the powers with which nature endowed me, and put them to their proper use ; that I was able to follow my innate bias, and think and work for many, while none did aught for me : this I owe to you, my father, I owe it to your activity, your wisdom, your frugality, your forethought for the future. Therefore I honour you, my noble father ; and therefore, whosoever finds any pleasure, comfort, or instruction in my work, shall learn your name, and know that if Heinrich Floris Schopenhauer had not been the man he was, Arthur Schopenhauer would have stumbled an hundred times. Let my gratitude render the only homage possible towards you, who have ended life : let it bear your name as far as mine is capable of carrying it.'

CHAPTER II - HIS STUDENT YEARS

[edit]THUS at seventeen, Arthur Schopenhauer was thrown on his own resources, for the chasm that divided him from his mother made itself felt immediately upon the father's death. The want of harmony among the strangely assorted elements of this family is scarcely astonishing. This circumstance, recognised or dimly discerned, probably explains their restlessness and preference for a nomadic existence. The abyss had not yet opened between mother and son, but the mental estrangement that must have existed for years evinced itself as soon as they were brought into personal contact, which up to this time had been little the case. Johanna Schopenhauer's volatility, optimism, and love of pleasure, repelled her son, and ever remained a puzzle to him, who, philosopher though he was, failed to make sufficient allowance for peculiarity of temperament, and condemned unsparingly whatever crossed his views. Neither could the mother understand her son, who fostered gloomy ideas of life, loved solitude, and was maddened beyond endurance by the social cackle politely termed conversation.

Arthur felt his father's loss acutely. To show deference to his memory he continued the hated mercantile pursuits, though daily his being rebelled more and more against the monotonous and soulless office routine. To be chained for life, as he thought, to a path so distasteful, deepened his depression.

Meanwhile Frau Schopenhauer made use of her liberty to remove to Weimar, then in the zenith of its glory as a centre of beaux esprits. Here her light- hearted spirit hoped to find more congenial ground than among the respectable Hamburg burghers, whose social meetings were all pervaded by a heavy commercial air, abhorrent to her aesthetic soul. Nor was she mistaken. Though the time of her arrival coincided with great historical convulsions,—just a fortnight before the battle of Jena and the military occupation of Weimar, a time therefore little adapted to the formation of social relations,—Frau Schopenhauer's energies and talent for society overcame all obstacles. In an incredibly short space she had formed a salon, collecting round her most of the great stars of that brilliant coterie.

To quote the words of her daughter, Adele, prefixed to her mother's unfinished memoirs, 'The time which followed (after the father's death), endowed her with a second spring of life, for Heaven granted to her then what is usually the privilege of early youth. With warm untroubled feelings she gazed into a world unrealized till then, though dreamt of long ago. Surprised at the rapid growth of her abilities, exalted by the sudden development of a latent talent, she experienced ever fresh delight in intercourse with the celebrated men resident at Weimar, or attracted thither by its stars. She was liked ; her society was agreeable. Her circumstances still permitted her to live in comfort, and to surround herself almost daily with her rich circle of friends. Her modest, pleasing manners made her house a centre of intellectual activity, where everyone felt at home, and freely contributed the best he had to bring. In the outline of her memoirs she names a few of the interesting men who frequented the salon. Numberless others came and went in the course of years, for despite all outward changes, her house long retained a faint afterglow of those halcyon days.'

Among these names figure European celebrities. First and foremost the mighty Goethe; then the brothers Schlegel and Grimm, Prince Pickler, Fernow (whose biography was Johanna Schopenhauer's literary début), Wieland, Meyer, &c. At court, too, the lively widow was a welcome guest. The terrible October days (1806) when Weimar woke to hear the thundering cannons of Jena, made but a temporary interruption to this intellectual life. The pillage of Weimar furnished Johanna Schopenhauer with matter for a lively letter to her son. She interrupted her narrative, however, by saying: 'I could tell you things that would make your hair stand on end, but I refrain, for I know how you love to brood over human misery in any case.'

This remark is characteristic and valuable, as it demonstrates the innateness of Schopenhauer's pessimism, and unanswerably refutes the contention of his adversaries, who choose to see in his philosophic views nothing but the wounded vanity and embittered moroseness of a disappointed man. This view will not apply to the case of a youth, nurtured in the lap of riches, who had led an independent, careless and interesting life. It is true he had lived through a year of bitter days, cooped up in an office, pursuing a detested vocation ; but a year's wretchedness, even though he at the time deemed it permanent, could not have developed in a healthy temperament such a deep disgust of life.

Still not even the reverence he paid his father's memory could keep him steadily to office work. He played truant to attend Gall's phrenological lectures; he wrote out his own thoughts under the cover of ledgers and letters ; he had abandoned all hope of making good his mistaken career, but he could not renounce all intercourse with learning. His melancholy increased, his letters abounded with invectives on his blighted fate. These complaints reached his mother, who for once could sympathise with her son. She consulted her Weimar friends concerning him, and received the comforting assurance that it was not too late for him to retrace his steps ; an assurance she hastened to communicate to Arthur, who received the news with a flood of tears. With impulsive decision he threw up business and hastened to Gotha, where, by the advice of Fernow, he was to enter upon his academic studies. He took private lessons in Greek and Latin, besides the usual curriculum; his progress was so rapid that the professors prophesied for him a brilliant future as a classical scholar, and his German writings showed a maturity of thought and expression that astounded everyone. Schopenhauer laid great stress upon the acquisition of ancient languages, and defended the study of Greek and Latin with all the ardour of a fanatical philologist, weighted with the heavy artillery of abusive utterance that characterised his speech and writing. Heine calls the Nibelungen-Lied an epic written with granite boulders. The criticism would not ill apply to Schopenhauer's massive, bold, lucid and relentless style.

Should the time ever come when the spirit that is bound up with the languages of the ancients shall vanish from our higher education, then barbarity, vulgarity and commonplace, will take possession of all literature. For the works of the ancients are the pole- star of every artistic and literary effort; if that sinks, you are lost. Already the bad, careless style of most modern authors shows that they have never written Latin. Occupation with the writers of antiquity has been aptly termed "humanitarian study," for through them the scholar becomes a man ; they usher him into a world free from the exaggerations of the Middle Ages and the Romantic School, which afterwards so deeply permeated European civilization, that even now, everyone enters life imbued with them, and must strip them off before he can be a man. Do not think your modern wisdom can ever prove a substitute for this regeneration; you are not born freemen like the Greeks and Romans; you are not unspoilt children of nature. You are above all the sons and heirs of the barbarous Middle Ages, with their absurdities, their disgraceful priestcraft, their half-brutal, half-ridiculous chivalry. Though both are coming to an end, you are not yet capable of standing alone. Without classical culture, your literature will degenerate into idle talk and dull pedantry. Your authors, guiltless of Latin, will sink to the level of gossiping barbers. I must censure one special abuse, which daily stalks forth more insolently: it is this, that in scientific books and in learned journals issued by academies, quotations from the Greek, and even those from the Latin, are given in a German translation. Fie, for shame! do you write for tailors and cobblers? I almost think you do, to command a large sale. Then permit me most humbly to remark that you are common fellows in every sense of the word. Have more honour in your souls and less money in your pockets, and let the uncultured man feel his inferiority, instead of scraping bows to his money-box. A German translation of Greek and Latin authors is a substitute similar to that which gives chicory in place of coffee; besides which you cannot even depend on its accuracy.'

Schopenhauer's success at Gotha cheered him and gave him renewed interest in life. He threw aside the apathy that had begun to envelope him at Hamburg, and entered heart and soul into his studies. Nor did this confine itself to study : Arthur Schopenhauer, the misanthrope, actually turned man of the world, pro tem. : sought the society of aristocrats, dressed with scrupulous care (a habit he retained through life), wore the newest-shaped garments, and squandered so much money that even his easy going mother urged him to practise more economy. His course at Gotha came to a sudden end, after six months' residence. A professor named Schulze, personally unknown to Schopenhauer, had publicly made some uncomplimentary remarks on the German class to which he belonged. Considering that the Professor had been wanting in the respect due to German gymnasiasts, Schopenhauer, with all the ardour of youth, gave vent to some sarcastic speeches on the subject, which, though delivered privately, were reported to the master, whose petty nature could not bear the irritation of sarcasm. He swore revenge, and succeeded in inducing Schopenhauer's private tutor, Doring, to discontinue his instructions. Under these circumstances, Schopenhauer held it to be incompatible with his honour to remain in the Gymnasium; he quitted Gotha in the autumn of 1807 and proceeded to Weimar. There he continued his preparatory collegiate studies. Weimar attracted him; he preferred to remain here rather than follow his mother's wishes, and enter another gymnasium. He did not, however, live under her roof, at her express desire.

'It is needful to my happiness,' she wrote to him shortly before his arrival, 'to know that you are happy, but not to be a witness of it. I have always told you it is difficult to live with you; and the better I get to know you, the more I feel this difficulty increase, at least for me. I will not hide it from you : as long as you are what you are, I would rather bring any sacrifice than consent to live with you. I do not undervalue your good points, and that which repels me does not lie in your heart; it is in your outer, not your inner being; in your ideas, your judgment, your habits; in a word, there is nothing concerning the outer world in which we agree. Your ill-humour, your complaints of things inevitable, your sullen looks, the extraordinary opinions you utter, like oracles none may presume to contradict; all this depresses me and troubles me, without helping you. Your eternal quibbles, your laments over the stupid world and human misery, give me bad nights and unpleasant dreams.'

In consequence of this letter, Schopenhauer settled in lodgings in Weimar. In the same house lived Franz Passow, two years his senior, who had also devoted himself to classical learning at Gotha, under Professor Jacobs, and who subsequently became a distinguished philologist. With Passow's aid and supervision, Scopenhauer penetrated yet further into the mysteries and riches of classical lore. His natural aptitude for learning languages helped him to repair lost time with incredible rapidity. He laboured day and night at Greek, Latin, Mathematics, and History, allowing nothing to divert his attention. Thus passed two rich busy years of mental culture, barren of external events save one : Schopenhauer's visit to Erfurt, where he was present at the famous congress of 1808, where kings and princes were plentiful as blackberries, and Napoleon, then at the acme of his power, lorded it over the assembly. He appears to have gained admission to the theatre, and seen the wonderful sight it presented when Talma and a chosen Parisian troupe played the finest tragedies of France before this 'parterre of kings.' He unsparingly lashes the contemptible frivolity of the court ladies, who cried down with Napoleon, as a 'monster,' before this evening, and after it cried him up again as 'the most amiable man in the world.'

On attaining his twenty-first year, in 1809, Schopenhauer decided on studying at the University of Gottingen, where he matriculated in the medical faculty. His stupendous energy never abated. During the first year of his residence he heard lectures on Constitutional History, Natural History, Mineralogy, Physics, Botany, and the History of the Crusades, besides reading at home on all cognate matters. He then passed into the philosophical faculty, devoting his attention to Plato and Kant, before attempting the study of Aristotle and Spinoza. Combined with his philosophical curriculum, he found time to attend lectures on Astronomy, Meteorology, Physiology, Ethnography, and Jurisprudence. He laid great stress on the advantages of viva voce instruction, though he has also admitted, in one of his manuscript books, c that the dead word of a great man is worth incomparably more than the viva vox of a blockhead.'

These manuscript books were a peculiarity of Schopenhauer's during all his university career. In them he noted down not only all he heard delivered, but his own criticisms and comments. He is often at variance with his masters, and says so in no measured terms, destroying their vantage ground with his relentless logic, or by some apt quotation. The many-sidedness of his acquirements becomes more and more remarkable as these note-books are perused. This trait is apt to bring superficiality in its train ; not so, however, with Schopenhauer, who applied himself with thoroughness to every subject he took in hand. He prided himself on his knowledge of the physical sciences, and always laid stress upon them when speaking of his philosophic system, largely influenced by this catholicity, for his works abound with illustrations drawn from all branches of science. To this he owed his large-mindedness, his scope; it is this separates him so widely from the generality of philosophers whose arguments and instances are solely derived from psychology. He had seen the world, he had studied the varied branches of human interests ; he was therefore competent to give an opinion. He acknowledges the fact when he says: 'This is why I can speak with authority, and I have done so honourably.' Later he writes on this subject to a disciple:

'I pray you, do not write on physiology in its relation to psychology, without having digested Cabanis and Bichat in succum et sanguinem ; in return you may leave a hundred German scribblers unread. At best the study of psychology is vain, for there is no Psyche ; men cannot be studied alone, but in connection with the world Microkosmus and Macrokosmus combined as I have done. And test yourself whether you really possess and comprehend physiology, which presupposes a knowledge of anatomy and chemistry.'

The records of his life, apart from studies, are meagre. He was certainly no German student in that ordinary acceptation of the word which implies a youth addicted to the imbibition of innumerable bumpers of beer, to playing of mad pranks, and duelling on the smallest provocation. Schopenhauer was a sworn enemy to the foolish practice of duelling, and has exposed its absurdities with his biting sarcasm and unerring logic. He treats its intellectual rather than its ethical aspect; disdaining to give emphasis to the palpable paradox that blind heathens had ignored the sublime principles of honour which are held as exigent by the followers of the gentle Preacher of the Mount. He shows how the point of honour does not depend on a man's own words and actions, but on another's, so that the reputation of the noblest and wisest may hinge on the tattling of a fool, whose word, if he chooses to abuse his fellow, is regarded as an unalterable decree, only capable of reversal by blood shedding ; disproof being of no avail. Superior strength, practice, or chance, decides the question in debate. There are various forms of insult; to strike a person is an act of such grave magnitude that it causes the moral death of the person struck; while all other wounded honour can be healed by a greater or lesser amount of blood, this insult needs complete death to afford its cure.

Only those conversant with the absurd lengths to which duelling has been carried at the German universities can fully appreciate Schopenhauer's bitterness. This essay on duelling was not published till the last years of his life, but it is incontestable that the youth shared the sage's views and acted upon them.

The only fellow-students Schopenhauer mentioned especially were Bunsen and an American, who had been attracted to him by his knowledge of English. The two were his habitual dinner companions. Schopenhauer later dwelt on the singular chance that made the three each realise in their person the three possible spheres of happiness he admits; dividing all possessions into what a man is, that which he has, and that which he represents. The American became a noted millionaire ; in Bunsen, Schopenhauer never recognised anything but a diplomatist, he ignored his literary activity, saying that a better Hebrew scholar was required to translate the Scriptures, and as for 'God in History,' that was only another name for Bunsen in History. His own lot he deemed the most important, though not the happiest or the most dazzling—that of a marked individuality. Bunsen, somewhat his senior, was warmly attached to Schopenhauer during their Göttingen residence, and hopes had been held out that he would furnish some biographical matter. But he died too soon after his early friend to admit of their realisation.

Before Schopenhauer quitted Göttingen he was fully assured that his bias was bent towards philosophy. Though ardently impressionable, he never carried enhusiasm beyond calm analytical judgment; and that he clearly recognised the sound core as well as the exterior prickles of the fruit for which he abandoned the active world, is proved by a letter written at this period.

'Philosophy is an alpine road, and the precipitous path which leads to it is strewn with stones and thorns. The higher you climb, the lonelier, the more desolate grows the way; but he who treads it must know no fear; he must leave everything behind him; he will at last have to cut his own path through the ice. His road will often bring him to the edge of a chasm, whence he can look into the green valley beneath. Giddiness will overcome him, and strive to draw him down, but he must resist and hold himself back. In return, the world will soon lie far beneath him ; its deserts and bogs will disappear from view; its irregularities grow indistinguishable; its discords cannot pierce so high; its roundness becomes discernible. The climber stands amid clear fresh air, and can behold the sun when all beneath is still shrouded in the blackness of night.'

Schopenhauer spent his vacations at Weimar, with the exception of one excursion into the Harz Mountains. In 1811 he quitted Göttingen for the University of Berlin, where he once more pursued a varied course of studies with eager energy. That first winter he attended Fichte's lectures on Philosophy, besides classes on Experimental Chemistry, Magnetism and Electricity, Ornithology, Amphibiology, Ichthyology, Domestic Animals, and Norse Poetry. Between the years 1812-13 he heard Schleiermacher read on the ' History of Philosophy since the time of Christ,' Wolf on the 'Clouds' of Aristophanes, the 'Satires' of Horace, and Greek antiquities, still continuing his natural history studies of Physics, Astronomy, General Physiology, Zoology, and Geology. How carefully he followed, his copious note-books prove. The most characteristic are those relating in any way to philosophy. His annotations grow more and more independent; the elements of his own system become more traceable as he differs from his professors, and explains his reasons for diverging from the beaten track. He does not hesitate to controvert their assertions, in language of unmistakable distinctness, occasionally in sarcasms more biting than refined. This habit of employing strong expressions increased with Schopenhauer's years, and is greatly to be regretted, as he could have easily been equally emphatic without recourse to a practice that exposed him to the imputation of vulgarity. This exercise of the clumsy weapons of abuse in place of dignified controversy is a serious blot on the escutcheon of German men of learning, and is doubly regrettable in Schopenhauer, who possessed a facility of wielding his native tongue quite unusual with ordinary writers, who seem to hold that the value of the matter is in inverse proportion to the merit of the manner. Schopenhauer's style was from the first clear, classical, and exact ; a circumstance he attributed in a great degree to his early training, which had been directed towards the more terse and nervous English and French authors in preference to the verbose German. It is this that makes the Germans so pre-eminently unreadable; and one of Schopenhauer's chief claims to hearing is his happy art of adapting himself to the meanest capacity. It is no small merit to say of a philosopher that his works will never stand in need of an expounder.

It was Fichte's fame that drew Schopenhauer to Berlin ; he hoped to find in his lectures the quintessence of philosophy, but his ' reverence a priori ' soon gave place to 'contempt and gibes.' The mystical sophistry and insolent mannerism of speech into which Fichte had drifted revolted Schopenhauer, who liked everything to be clear and logical. Fichte's personality repelled him, as well as his delivery. He would often imitate the little red-haired man trying to impose upon his hearers with the hollow pathos of such phrases as : ' The world is, because it is; and is as it is, because it is so.' Notwithstanding this speedy disenchantment, Schopenhauer continued to hear these abstruse discourses, and eagerly disputed their dicta in the hours devoted to controversy. His notes abound in criticisms of Fichte. He heads the manuscript book devoted to this purpose with the words 'Wissenschaftslehre,' and writes in the margin, Perhaps the more correct reading is 'Wissenschaftsleere,' playing on the resemblance of the words study and emptiness; thus, the study of science and the emptiness of science. In another place he complains of the difficulty he finds in following Fichte. His delivery, he says, is clear and deliberate enough, but he dwells so long on things easy to comprehend, repeating the same idea in other words, that the attention flags with listening to that which is already understood, and becomes distracted.

Schopenhauer regarded an expression used in one of the first lectures he heard as so striking a proof of psychological ignorance as almost to unfit its holder to the title of philosopher. Fichte asserted that genius and madness are so little allied that they may be regarded as utterly divergent, defining genius as godlike, madness as bestial. To this lecture Schopenhauer appends a lengthy criticism, which contains the complete germ of his own Theory of Genius:—

'I do not hold that the maniac is like an animal, and that the healthy reason stands midway between insanity and genius ; on the contrary, I believe that genius and insanity, though widely different, are yet more nearly related than is the one to ordinary reason and the other to animality. An intelligent dog may be more properly compared to an average, well balanced, intelligent man, than to a maniac (not an idiot). On the other hand, lives of men of genius show that they are often excited like maniacs before the world. According to Seneca, Aristotle says: "Nullum magnum ingenium sine insanise mixtura." I affirm that a healthy intelligent man is firmly encased by the corporeal conditions of thought and consciousness (such as are furnished by space, time and definite ideas); they enfold him closely, fit and cover him like a well-made dress. He cannot get beyond them (that is, he cannot conceive of himself and of things in the abstract, without those conditions of experience); but within these bounds he is at home. The same thing holds good of a healthy animal, only that its conception of experience is less clear; its dress, we might say, is uncomfortable, and too wide. Genius, in virtue of a transcendental power which cannot be defined, sees through the limitations which are the conditions of a conception of experience, seeks all his life long to communicate this knowledge, and acts by its light.

To continue my simile, we might say that genius is too ample for its dress, and is not wholly clad by it. The conditions of a conception of experience have been disturbed for the maniac ; his laws of experience have been destroyed, for these laws do not pertain to the things themselves, but to the manner in which our senses conceive them (which is confirmed in this case); everything is embroiled for him; according to my simile, his dress is torn, but just for that very reason his ego, which is subject to no disturbance, looks through occasionally. Maniacs make remarks full of genius, or rather would make them, if that clear consciousness which is the very essence of genius were not wanting. . . . Take for instance King Lear, who is certainly correctly drawn ; is he nearer to animality or genius ?

'On the other hand, genius often resembles insanity; because, by dint of looking at things in the abstract, it is less acquainted with the world of experience, and, like the maniac, confuses ideas by realising things in the abstract at the same time. Just as Shakespere's Lear is a representation of insanity combined with genius, so Goethe's Tasso is a representation of genius combined with insanity. The idiot is more like an animal; to continue my simile, I should say that he has shrivelled up, and cannot fill out his dress, which hangs loosely about him; far from looking out beyond it, he cannot even move about in it freely; he is completely like an animal. Every stupid person approaches this condition, more or less. Of every worldly-wise man the contrary is true, his dress fits him like a glove. From animality and idiotcy we arrive by degrees to the greatest cleverness. But genius and insanity are not the first and the last steps of the series, but integrally different, as I have said.'

Schopenhauer's disparaging opinion of Fichte has been quoted as a proof of conceit, but passages in his works prove that it did not spring from mere arrogance. He opposed the common error that Fichte had continued the metaphysical system raised by Kant, and contended that on the contrary he had absolutely swerved from his master's tenets, which were far more those of searching logic than of misty metaphysics. He is fair, too ; a marginal note to one of the propositions in the course of Fichte's lectures on 'Wissenschaftslehre' reads: 'Though this be madness, yet there's method in it.' Occasionally he breaks off his memorandum, saying that owing to the obscure phrases bandied, the air had grown so dark in the lecture room that he could not see to write, and that the lecturer had only provided a tallow candle to illuminate the hall. Or, again, when Fichte repeats the words 'seeing,' 'visibility,' 'pure light,' Schopenhauer writes in the margin : 'As he put up the pure light today instead of the tallow candle, this précis could not be continued.' At another time he remarks : ' It was so dark in the hall that Fichte was able to abuse others quite at his ease.'

Schleiermacher was the second celebrity that attracted Schopenhauer, and again he was destined to disappointment. He began to differ from him also after the first lecture. Schleiermacher said:

'Philosophy and Religion have the knowledge of God in common.'

'In that case,' annotes Schopenhauer, 'philosophy would have to presuppose the idea of a God; which, on the contrary, it must acquire or reject impartially according to its own development.

Schleiermacher announced that 'Philosophy and Religion cannot exist apart; no one can be a philosopher without a sense of religion. On the other hand, the religious man must study the rudiments of philosophy.'

'No one who is religious,' writes Schopenhauer, arrives as far as philosophy; he does not require it. No one who really philosophizes is religious; he walks without leading strings; his course is hazardous but unfettered.'

'This Schleiermacher is a man in a mask,' he would, say. In after years he told choice anecdotes about him, and repeatedly praised his remark that a man only learnt at the University to know what he would have to learn afterwards. The characters of Schleiermacher and Schopenhauer were too fundamentally at variance to admit of any assimilation. Schopenhauer was besides repelled by Schleiermacher's personal appearance a point on which he was extremely sensitive so that the two great men never came into immediate contact; a matter the more regrettable as Schleiermacher loved nothing so much as colloquial intercourse. Such meetings might have modified the younger man's unfairness to one who, great as are his errors, was undoubtedly the precursor of a new epoch in Protestant theology. But theology and jurisprudence were the only two branches of learning which Schopenhauer left out of regard in his studies and his writings.

His favourite professor was Heinrich August Wolf, the great Hellenist and critic, a fact that honours both master and pupil. His notes of Wolf's lectures abound in praise, while those relating to the History of Greek Antiquities are furnished with marginalia 'in Wolf's own handwriting,' as Schopenhauer appends with youthful pride at such distinction from, a revered master. It was no wonder that this philosopher, whose startling theories set the whole classical world ablaze, and whose works are justly considered models of controversial writing and refined irony, appealed to a mind that had so much in common with his own.

CHAPTER III - HIS MENTAL DEVELOPMENT

[edit]SCHOPENHAUER, like Goethe, was devoid of political enthusiasm; he pursued his studies regardless of mighty events that determined the fate of nations. These were the winter months of 1812 and 1813, when Europe throbbed with hopes of deliverance from the thraldom of Napoleon; his disastrous Russian campaign awakening and justifying these feelings. The rousing appeals to the German nation which Fichte had thundered forth with fearless energy in the winter of 1808, during the French occupation of Berlin, bore fruit now that the first chance of success dawned. Schopenhauer never mentions these addresses when he censures Fichte. Whatever views he held of his philosophy, he might have accorded a word of praise to this unflinching patriotism.

When the unsettled state of affairs after the indecisive battle of Lützen convinced Schopenhauer that this was not a likely time to receive promotion at Berlin, he merely went out of the way of these martial disturbances to meditate his inaugural dissertation. He need not be blamed for this apparent callousness any more than Goethe. Genius must be egotistic in a certain sense; it must place self-culture in the chief position; this very egotism is an element inalienable from its due development. Small and narrow spirits cannot comprehend, and therefore condemn this instinctive self-enclosure within which true genius unfolds. Schopenhauer had not Goethe's amiability to conciliate them in other ways, his was a harsh uncompromising temperament; yet he too felt he had his mission towards the world, and he must fulfill it after his bent. To say he was devoid of political enthusiasm is not to say that he was devoid of patriotism, a quality not necessarily or always free from selfish motives, as its ardent and often most egotistic admirers aver. Schopenhauer was certainly free, almost to a fault, from the weakness of national pride. His patriotism was limited to the German language, whose powerful beauties he appreciated so keenly that it maddened him to see it wielded in the clumsy grasp of ordinary writers. He was never weary of contrasting the English and French authors with those of his own country, greatly to the disadvantage of the latter. He was disgusted at the Germans' negligence of what he esteemed their only treasure. In every other point of view he was ashamed to be a German, and gladly recalled his paternal Dutch descent. Those were the days of tall talk and tiny deeds ; small wonder therefore if they met with little sympathy from a man of Schopenhauer's energetic mould. Yet in his innermost heart must surely have lurked some love of country; else why did he blame so severely in his own nation actions which he could overlook or excuse in others? Doubtless had Schopenhauer lived to witness late events he would have been as good a patriot as any.

Throughout life he hated interruptions. When therefore the tumult of war approached Berlin, Schopenhauer fled to Saxony. It took him twelve days to reach Dresden, owing to the disturbed state of the country. Ill-luck made him fall into the very midst of the army, and he was once retained as interpreter between the French and German troops, his knowledge of the former language having attained for him this unenviable distinction. He then proceeded to Weimar, but did not stay many days. Circumstances had arisen in his mother's circle that caused him to accuse her of want of fidelity to his father's memory. Whether these allegations were sufficiently proved remains doubtful; Dr. Gwinner, Schopenhauer's friend and biographer, inclines to think they were not. In any case, Schopenhauer believed them just; and they threw dark shadows over his future life, and helped yet further to separate him from his surviving parent. He retired to Rudolstadt, a charming little town in the Thuringian forest, to ponder in peace over his inaugural dissertation.

Mental work was not as easy as might be assumed from reading his flowing periods. Thought came freely enough at times ; at others it had to be secured or exhumed, and any casual noise would interrupt the thread of his reasoning. He dwells on this in the 'Parerga,' and mentions it more fully, with especial reference to his own case, in a MS. book of the Rudolstadt period.

'If I faintly perceive an idea which looks like a dim picture before me, I am possessed with an ineffable longing to grasp it; I leave everything else, and follow my idea through all its tortuous windings, as the huntsman follows the stag; I attack it from all sides and hem it in until I seize it, make it clear, and having fully mastered it, embalm it on paper. Sometimes it escapes, and then I must wait till chance discovers it to me again. Those ideas which I capture after many fruitless chases are generally the best. But if I am interrupted in one of these pursuits, especially if it be by the cry of an animal, which pierces between my thoughts, severing head from body, as by a headsman's axe, then I experience one of those pains to which we made ourselves liable when we descended into the same world as dogs, donkeys, and ducks.'

This excessive sensitiveness to noise caused Schopenhauer much suffering through life. He regarded it as a proof of mental capacity ; stoic indifference to sound was to his mind equivalent to intellectual obtuseness.

As Schopenhauer's early MS. books embodied the original foundation of those ideas which his later works merely amplified, so they are also a species of self analysis. He studied his own subjectivity, and drew his conclusions for the general out of the individual. He speaks of himself, often to himself, and thus makes us acquainted with his moral and intellectual entity.

All the thoughts which I have penned,' he says, in his MS. book 'Cogitata, 'have arisen from some external impulse, generally from a definite impression, and have been written down from this objective starting-point without a thought of their ultimate tendency. They resemble radii starting from the periphery, which all converge towards one centre, and that the fundamental thought of my doctrine; they lead to this from the most varied quarters and points of view.'

The same idea is expressed in the 'Spicilegia,' a later memorandum-book, thus proving the perfect unison of purpose that pervaded this robust life.

'My works are a succession of essays, in which I am possessed with one idea I wish to determine for its own sake by writing it down. They are put together with cement, therefore they are not shallow and dull, like the works of people who sit down to write a book page by page, according to some preconceived plan.'

The dissertation he was evolving at Rudolstadt had to be complete and symmetrical, and accordingly cost him much labour. He enjoyed the calm country atmosphere that surrounded him, its solitude was congenial, and when there were no noises he was well content. But as he lived in the Inn, where to this day a line from Horace, scratched by him on a pane, is shown to visitors, such disturbances cannot have been quite avoidable. It runs : 'Arth, Schopenhauer, majorem anni 1813 partem in hoc conclave degit. Laudaturque domus, longos quæ prospicit agros.' It seems as if there must have been an obnoxious baby on the premises, to judge from the somewhat petulant remark he wrote there :—

'It is just, though hard, that we should daily, our whole life long, hear so many babies cry, in return for having cried a few years ourselves.'

Two letters of this period are extant. They are of no intrinsic importance, but deserve quotation because they reveal Schopenhauer in an amiable and social light, after he had already acquired the character of a misanthrope. Perhaps the soothing intercourse with the pleasing scenery of Thuringia had exercised some charm even over this morose spirit, or, more likely still, Schopenhauer was at heart an amiable man, forced to put on an exterior armour of gruffness as protection from those who should have been his warmest friends, and proved his most irritating, disdainful enemies. Later the mail became a part of the man, so that Noli me tangere might aptly have been Schopenhauer's motto.

The first letter is undated, an habitual negligence, and characteristic, like all he did. He was the champion of Kant, who preached that time is not a real existence, but only a condition of human thought. The letters are both addressed to Frommann, the publisher and bookseller of Jena, at whose house Goethe met Minna Herzlieb, the love of his advanced age and the heroine of his 'Elective Affinities.'

'DEAR SIR,

'I must, perforce, furnish a commentary to the

chapter "On the vanity of human intentions and

wishes." Yesterday I feared it would rain, and today,

in spite of the most beautiful weather, I am a prisoner

to my room, and that because a new shoe has nearly

lamed me, and would have done so quite had I gone

out again today. So I am having the shoe stretched,

and am holding a festival of rest and penance in honour

of St. Crispin, the patron of shoemakers.

'I am only sorry that this mishap prevents me from having the pleasure of seeing you and your charming family. Professor Oken has kindly sent me some books, with which I pass my time agreeably. I have everything I need, and I sincerely hope that you will not allow my being here to disturb your plans. I only let you know because I wish to ask you to tell Herr von Altenburg, who seeks a travelling companion through this neighbourhood, that I shall be happy to accompany him, if it suits him to go to-morrow evening.

'Please remember me to your family, and believe me sincerely yours,

- 'ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER.'

Meanwhile Schopenhauer's first work was completed, and sent in to the University of Jena, which bestowed on him the too-often abused title of Doctor of Philosophy. This, 'Die Vierfache Wurzel des Satzes vom Zureichenden Grunde,' already contained the germs of his entire philosophy.