Bill the Minder/Good Aunt Galladia

GOOD AUNT GALLADIA

AT first the King seemed disposed to be not a little irritable towards the triplets, murmuring something to himself about the extra expense. A good lunch, however, soon put him to rights, and he was his old cheerful self again.

In the afternoon they met upon the road a long thin man with a grin of the greatest self-satisfaction widening his otherwise narrow face. In one hand he carried a cage containing a miserable old bird that could hardly boast an egg-cupful of feathers on its whole shrivelled body; in the other he carried a large wooden box. He very good-naturedly stood aside for the army to move on, but the King, whose curiosity had been aroused, would not allow him to be passed unquestioned, so he rang a little bell he always carried with him for the purpose, and the whole force at once stopped short. In obedience to a signal from the King, the long man stepped jauntily before him. 'Anything wrong, old chirpy?' said he, addressing the King rather rudely as some thought. 'Not with me,' the King replied with much dignity. 'My only reason for calling you before me is to learn why you are so extremely pleased with yourself. Such a secret would be of the greatest value to us all.' 'Because she's given these back to me,' answered the long fellow as he opened his box and disclosed, all neatly arranged, a beautiful collection of birds' eggs. Every kind appeared to be there, and all of the most beautiful colours imaginable.

'But who is she?' queried the King.

'Why, my good Aunt Galladia, of course, but it's too long a story to tell standing up, so let us sit down by the roadside, and you shall hear all about it.'

Every one now seated themselves on the grass by the side of the road and over a comforting cup of tea, speedily brewed by Boadicea, the long man began his story:—

'My good aunt's full name was Galladia Glowmutton, and she was the only daughter of that gallant general, Sir Francis Melville Glowmutton, who distinguished himself so greatly in the defence of his country.

'It was my good fortune to spend my earliest days in this good creature's company, she, noble soul that she was, having undertaken to look after me when my poor father and mother disappeared in a sand-storm many years before.

'The greater part of her life this good woman had devoted to brightening the declining years of her well-loved father, whose arduous life, poor man, had left him in his old age, truth to tell, rather a tiresome, and sometimes a difficult, subject to get on with. However, thanks to her devotion and patience, he led a tolerably happy life. In the course of time the old warrior died and left the sorrowing lady well provided for,—that is, over and beyond necessaries, with sufficient money to keep up appearances, and even enough for her simple pleasures and hobbies.

'For some months my good aunt could not fill the blank in her life left by the loss of her father. So much kindness, however, could not be kept back for long, and was bound in the course of time to find its object. Always with a love for every feathered creature, she at last set about gathering around her as complete a collection of them as she could obtain. Soon she had in her aviaries the most marvellous assembly of birds ever brought together even at the Zoo. There were specimens of the Paraguay gull, Borneo parrots, Australian gheck ghees, the laughing grete, Malay anchovy wren that only feeds upon anchovies (and very amusing indeed it is, too, to watch them spearing the little fish with their beaks and then trying to shake them off again), and the golden-crested mussel hawk, that swoops down from an incredible height and, snatching its prey from the rocks, again disappears in the sky. Without wearying you with a long list, nearly every known bird was represented in my aunt's collection, from the fierce saw-beaked stork of Tuscaroca to the mild and pretty little Gossawary chick.

'Much as she prized every one of her pets, she loved most of all the very rare and beautiful green-toed button crane of Baraboo. So fond was she of the stately creature, and so careful of its every comfort, that she employed a maid to wait on it alone, and a special cook to prepare its meal of Peruvian yap beans, the delicious and tender kernels of which the dainty creature was inordinately fond of,—and, indeed, they were the only food upon which it throve.

'Now, with your permission, a few words about myself. Like my aunt I, too, had birdish leanings, but unlike her in this, that instead of birds I collected birds' eggs, of which I had a vast number of every conceivable variety. Ashamed as I am to state it, little did my good Aunt Galladia know how many of the valuable specimens in my collection were taken from her aviaries. Nevertheless she viewed my specimens with growing suspicion, until at last she implicitly forbade me to collect any more. For a time I desisted, and merely contented myself with gloating over my already vast collection, but in a little while temptation became too strong for me and I resumed my pursuits.

'One afternoon about this time I had mounted a tall tree in the Glowmutton Park, intent on obtaining the contents of a nest built in its highest branches. For some time I was unable to approach the nest, but at length, by dint of much perseverance, I just managed to reach my hand over the top, and took therefrom three beautiful eggs, of a kind as yet unrepresented in my collection. So occupied was I with my prize, that I did not at first observe what was taking place beneath the tree. But on beginning to descend, I saw to my horror immediately below me, my Aunt Galladia and her pet crane seated at tea, with the crane's maid in attendance.

'Needless to say I did not continue my descent, but climbed out to the end of a branch, high over the group. I waited in dreadful suspense in the hope that my aunt would not look up, and that they would soon finish their meal and depart as quickly as they had arrived, but, alas! they were in no hurry. I trembled now so much that I could hear the leaves rustling on the branch, and whether it was that in my fear I loosened my hold, or that the branch shook so under my trembling form, or whether the sight of a

I JUST MANAGED TO REACH THE EGGS

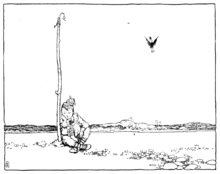

I ANGLE THE AIR

collection of eggs. "Never," shrieked my wrathful aunt, "shall you have these again until you bring back to me my beautiful crane."

'After a while I recovered, but no one dared to speak to me, and I moped about the house in solitary wretchedness without a single egg to contemplate.

'At last I could bear it no longer, and one night I left the house determined never to return again without the crane. I took with me an old perambulator, in which I had been wheeled about as a child, and I fell from my position

I ERECTED MY POLE ON THE SANDS

in this I placed six of the delicious kernels of the Peruvian yap bean, besides a hatchet and other things which I thought might be useful on my journey. I slept in the forest and, on the following morning I cut down the straightest tree I could find for my purpose, trimmed it to a fine long pole, and on the very top of this I fastened a pin, bent to the form of a fish-hook, which I now baited with one of the yap kernels.

'"If anything will attract the bird, this will," thought I, having fastened the foot of the pole to my perambulator. I now proceeded to angle the air for the lost crane. Carefully following the direction I had observed the bird to take when it broke away from its chain, I travelled for weeks and weeks, without seeing any sign of it. In time, without even a nibble, the first kernel was dissolved and worn away by the wind and rain, and, in like manner the same fate overcame the second, with which I baited my hook; then the third, then the fourth, and then the fifth.

'Still keeping the same direction, by this time I had arrived at the very edge of the world, beyond which there is nothing but sea and sky. Believing that the poor creature had flown out over this lonely sea, and hoping that it might return when it realised that there was no land beyond, I determined to wait on the desolate shore.

'I now erected my pole on the sands, after once more baiting my hook, this time with a piece of my last kernel, having taken the precaution of cutting it into six pieces. I now waited patiently, week after week, subsisting on the oysters, the starfish, and the edible crustaceans, that wandered tamely about the shore. Months now passed by, and, one by one, the five pieces of my last yap kernel had followed the other five kernels with which I had set out from home. I am not easily beaten, however, and though many months had passed by without my meeting with any success, I would not give in, but husbanded my last piece of bait with the greatest care. I cut a chip of wood from my angling pole, and shaped it in the form

ITS OLD STATELY SELF AGAIN

of a kernel of the Peruvian yap bean. This I rubbed well all over with the tiny piece of the real kernel that yet remained to me, until it assumed somewhat the colour of the original bean and, certainly, when applied to the tip of the tongue, it appeared to partake, though very slightly, it is true, of the original flavour, and with this I once more baited my hook.

'By this means I made my last piece of bean last for some years, for as soon as the artificial bean had lost its flavour, I rubbed it up again with the real one. But even this could not go on for ever, and, at last, the true piece was worn right away; so, to preserve what little flavour there yet remained of the true bean in the false bean, on which it had been so often rubbed, I soaked it for six days in a large shell of rain-water. In the meantime I cut another chip from my pole, and spent nearly six days in carving out another artificial kernel. Before baiting my hook with this, I dipped it into the fluid in which the old wooden kernel was still soaking, whence it received a very very faint suggestion of the original flavour, but so faint was this that it had to be redipped three times a day. This went on for some time, until the precious liquor began to run low, and I was compelled to dilute it still further, in the proportion of about five drops to a mussel-shellful of water, into which the wooden kernel was now dipped ten or twelve times a day.

'Well, I had been at this game, I should say, getting on for twenty years, and now resolved to have done with it, after risking all on one throw. So I dropped my wooden kernel, all rotted and weather-beaten as it was, into what little there remained over of the pure liquor, this time without diluting it at all, and then let it stew all day in the sun.

'In the evening the liquor was all evaporated, and the wooden bean seemed to the taste as though it possibly might have been in the vicinity of a real one some time before. On that evening, for the last time, I baited my hook and slept soundly at the foot of the pole.

'I was awakened next morning by the wind that had arisen during the night, and a great wrenching noise, as it tore my poor old angling-pole from its place in the sand, and carried it out to sea.

'"That settles it once and for all," thought I, much relieved, "and I'm off home," and I set about getting my things together. While I was thus engaged, it occurred to me that the old pole might be useful for fires, so I swam out for it. Already it had been blown some way out to sea, and, as the tide was against me, it was only with a very great exertion of strength that I gained at all upon it, and I was just about to give it up when I beheld, fastened to the bent pin at the end of the pole, the wretched crane. The sight lent me greater strength, and, after incredible exertions, I reached the pole almost exhausted. We were now too far from the shore to attempt to return, so I got astride the pole, and immediately proceeded to unfasten the unhappy fowl from my bent pin. At first I thought the poor thing dead, but I nursed it in my arms all through the ensuing night, and, on the following morning, happening to glance down its half-opened beak, I could just see that my wooden imitation of the kernel of the Peruvian yap bean had become lodged in its throat. This I at once removed, and, to my great joy, the dejected fowl almost immediately opened its eyes. Soon it became its old stately self again, though now I could see that the poor thing had aged very considerably since it left home.

'Well, to cut a long story short, at length the gale ceased, and we landed safely on the shore, much nearer to our home, and, after many vicissitudes and adventures, of which I shall have great pleasure in telling you at another time, we eventually arrived at Glowmutton Castle.

'To my grief I learnt that my good aunt, Galladia, had died many years before of old age, and that, true to her own good-nature, her last commands were that if ever I should return with her dearly-loved fowl, my collection of eggs was to be handed back to me, and in recompense for all my privations and exertions to recover the bird, I was to have the care of it and the comfort of its society as long as it lived. So, now you see why I am so pleased with myself

The King and the whole army were charmed with the recital, and the long man, whose many noble qualities had already endeared him to them, was cordially invited to join the forces.

'It's all one to me, my cronies,' said the good-natured creature, and they all trudged on.