Bird Watching/Chapter 3

I have alluded to the aerial combats of the stock-dove during the nuptial season as elucidating similar movements on the part of the peewit, though I was not able so fully to satisfy myself as to the meaning of these in the latter bird. The fighting of birds on the wing has sometimes—to my eye, at least—a very soft and delicate appearance, which does not so much resemble fighting as sport and dalliance between the sexes. Larks, for instance, have what seem, at the worst, to be delicate little mock-combats in the air, carried on in a way which suggests this. Sometimes, rising together, they keep approaching and retiring from each other, with the light, swinging motion of a shuttlecock just before it turns over to descend, and this resemblance is increased by their flying perpendicularly, or almost so, with their heads up and tails down. Indeed, they seem more to be thrown through the air than to fly. Then, in one fall, they sink together into the grass. Or they will keep mounting above and above each other to some height, and then descend in something the same way, but more sweepingly (for let no one hope to see exactly how they do it), seeming to make with their bodies the soft links of a feathered chain—or as though their own "linked sweetness" of song had been translated into matter and motion. In each case they make all the time, as convenient, little kissipecks, rather than pecks, at each other.

Again, in the case of the redshank, though I have little doubt now that the following, which was both aquatic and aerial, was a genuine combat between two males, yet often at the time, and especially in its preface and conclusion, it seemed as though the birds were of opposite sexes, and, if fighting at all, only amorously.

"Two birds are pursuing each other on the bank of the river. The water is low, and a little point of mud and shingle projects into the stream. Up and down this, from the herbage to the water's edge and back again, the birds run, one close behind the other, and each uttering a funny little piping cry—'tu-tu-oo, tu-oo, tu-oo, tu-oo.' It is one, as far as I can see, that always pursues the other, who, after a time, flies to the opposite bank. The pursuer follows, and the chase is now carried on by a series of little flights from bank to bank, sometimes straight across, sometimes slanting a little up or down the stream, whilst sometimes there is a little flight backwards and forwards along the bank in the intervals of crossing. This continues for something like an hour, but at last the pursuing bird, as both fly out from the bank, makes a little dart, and, overtaking the other one, both flutter down into the stream. They rise from it straight up into the air like two blackbirds fighting, then fall back into it again, and now there is a violent struggle in the water. Whilst it lasts the birds are swimming, just as two ducks would be under similar circumstances, and every now and then, in the pauses of exhaustion, both rest, floating on the water. The combat would be as purely aquatic as with coots or moor-hens, if it were not that the two birds often struggle out of the water and rise together into the air, where they continue the struggle, each one rising alternately above the other and trying to push it down—it would seem with the legs. These were the tactics adopted in the water too, but yet, with a good deal of motion and exertion, there seems but little of fury. The birds are not acharné, or, at least, they do not seem to be. It is a soft sort of combat, and now it has ended in the combatants making their mutual toilette quite close to one another. One stands on the shore and preens itself, the other sits just off it on the water and bathes in it like a duck."

Even here, owing principally to the friendly toilette-scene, I was not quite clear as to the nature of the bird's actions. How completely I at first mistook it in the case of the stock-dove with the way in which it was afterwards made plain to me, the following will show:—

"Most interesting aerial nuptial evolutions of the male and female stock-dove.—They navigate the air together, following each other in the closest manner, one being, almost all the while, just above the other, their wings seeming to pulsate in time as soldiers (if sweet birds will forgive such a simile) keep step. Now they rise, now sink, making a wide, irregular circle. Both seem to wish, yet not to wish, to touch, almost, yet not quite, doing so, till, when very close, the upper one drops lightly towards the one beneath him, who sinks too; yet for a moment you hear the wings clap against each other. This sounds faintly, though very perceptibly; but the distance is great, and it must really be loud. Every now and again the wings will cease to vibrate, and the two birds sweep through the air on spread pinions, but, otherwise, in the manner that has been described. I must have watched this continuing for at least a quarter of an hour before they sunk to the ground together, still maintaining the same relative position, and with quivering wings as before. Here, however, something distracted me, the glasses lost them, and I did not see them actually alight. Another pair rise right from the ground in this manner,[1] one directly above the other, quiver upwards to some little height, then sweep off on spread pinions, following each other, but still at slightly different elevations. They overtake one another, quiver up still higher, with hardly an inch between them, then suddenly, with an, as it were, 'enough of this,' sweep apart and float in lovely circles, now upwards now downwards. As they do this another bird rushes through the air to join them, he circles too, all three are circling, the light glinting on one, falling from another, thrown and caught and thrown again as if they played at ball with light."

I thought, therefore, that birds when they flew in pairs like this were disporting themselves together in a nuptial flight, and making—as indeed this, in any case, is true—a very pretty display of it. What was there, indeed—or what did there seem to be—to indicate that angry passions lay at the root of all this loveliness? But I had not taken sufficiently into consideration that sharp clap of the wings indicating a blow—a severe one—on the part of one of the birds with a parry on that of the other. This is how stock-doves, as well as other pigeons, fight on the ground, and it is as an outcome and continuation of these fierce stand-up combats—which there is no mistaking—that the contending birds rise and hover one over the other, in the manner described. My notes will, I think, show this, as well as the curious and, as it were, formal manner in which the ground-tourney is conducted.

"Two stock-doves fighting.—This is very interesting and peculiar. They fight with continual blows of the wings, these being used both as sword—or, rather, partisan—and shield. The peculiarity, however, is this, that every now and again there is a pause in the combat, when both birds make the low bow, with tail raised in air, as in courting. Sometimes both will bow together, and, as it would seem, to each other—facing towards each other, at any rate—but at other times they will both stand in a line, and bow, so that one bows only to the tail of the other, who bows to the empty air. Or the two will bow at different times, each seeming more concerned in making his bow than in the direction or bestowal of it. It is like a little interlude, and when it is over the combatants advance, again, against each other, till they stand front to front, and quite close.

Both, then, make a little jump, and battle vigorously with their wings, striking and parrying. One now makes a higher spring, trying, apparently, to jump on to his opponent's back, and then strike down upon him. This is all plain, honest fighting, but there is a constant tendency—constantly carried out—for the two to get into line, and fight in a sort of follow-my-leader fashion, whilst making these low bows at intervals. It is a fight encumbered with forms, with a heavy, punctilious ceremony, reminding one of those ornate sweeps and bowing rapier-flourishes which are entered into before and at each pause in the duel between Hamlet and Laertes, as arranged by Sir Henry Irving at the Lyceum. There were four or five birds together when this fight broke out, but I could not feel quite sure whether the non-fighting ones watched the fighting of the other two. If they did, I do not think they were at all keenly interested in it. Also, the fighting birds may sometimes, when they bowed, have done so to the birds that stood near, but it never seemed to me that this was the case, and it certainly was not so in most instances."

In the spring from the ground which one of the fighting birds sometimes makes, coming down on the other one's back and striking with the wings, we have, perhaps, the beginning of what may develop into a contest in the clouds, for let the bird that is undermost also spring up, and both are in the air in the position required; and it is natural that the undermost should continue to rise, because it could more easily avoid the blows of the other whilst in the air, by sinking down through it, than it could on the ground at such a disadvantage. Whether, in the following instance, the one bird jumped on to the other's back does not appear, but, as will be seen, the flight, which I had thought to be of a sexual and nuptial character, was the direct outcome of a scrimmage. "A short fight between two birds.—It is really most curious. There is a blow and then a bow, then a vigorous set-to, with hard blows and adroit parries, a pause with two profound bows, another set-to, and then the birds rise, one keeping just above the other, and ascend slowly, with quickly and constantly beating wings, in the way so often witnessed. It would appear, therefore, that the curious flights of two birds up into the air, the one of them exactly over, and almost touching, the other—wherein, as I have noted, there is frequently a blow with the wings which, to judge by the sound reaching me from a considerable distance, must be sometimes a severe one—are the aerial continuations of combats commenced on the ground." Sometimes, that is to say. There seems no reason why birds accustomed thus to contend, should not sometimes do so ab initio, and without any preliminary encounter on mother earth—and this, I believe, is the case.

Here, then, in the stock-dove we have at the nuptial season a kind of flight which seems certainly to be of the nature of a combat, very much resembling that of the peewit at the same season. I have seen peewits fighting on the ground, and once they were for a moment in the air together at a foot or two above it, and the one a little above the other. This, however, may have been mere chance, and I have not seen the one form of combat arise unmistakably out of the other, as in the case of the stock-doves. But assuming that in each case there is a combat, is it certain that the contending birds are always, or generally, two males, and not male and female? It certainly seems natural to suppose this, but with the stock-dove, at any rate (and I believe with pigeons generally), the two sexes sometimes fight sharply; and, moreover, the female stock-dove bows to the male, as well as the male to the female, both which points will be brought out in the following instances:—

"A hen bird is sitting alone on the sand, a male flies up to her and begins bowing. She does not respond, but walks away, and, on being followed and pressed, stands and strikes at her annoyer with the wings, and there is, then, a short fight between the two. At the end of it, and when the bowing pigeon has been driven off and is walking away, having his tail, therefore, turned to the one he is leaving, this one also bows, once only, but quite unmistakably. The bow was directed towards her retiring adversary, and also wooer, the two birds therefore standing in a line." And on another occasion "A stock-dove flies to another sitting on the warrens, and bows to her, upon which she also bows to him. Yet his addresses are not successfully urged."

The sexes are here assumed, for the male and female stock-dove do not differ sufficiently for one to distinguish them at a distance through the glasses. When, however, one sees a bird fly, like this, to another one and begin the regular courting action, one seems justified in assuming it to be a male and the other a female. Both, however, bowed, and there was a fight, though a short one (I have seen others of longer duration), between them. It becomes, therefore, a question whether the much more determined fights which I have witnessed are not also between the male and the female stock-dove, and not between two males. If so, the origin of the conflict is, probably, in all such cases—as it certainly has been in those which I have witnessed—the desires of the male bird, to which he tries to make the female submit. That she, in the very midst of resisting, taken, as it would seem, "in her heart's extremest hate," should yet bow to her would-be ravisher seems strange, but she certainly does so. Whether it would be more or less strange that two male birds, whilst fiercely contending, should act in this way, I will leave to my readers to decide, and thus settle the nature of these curious ceremonious encounters and their graceful and interesting aerial continuations, to their own satisfaction.[2]

However it may be, the bow itself—which I will now notice more fully—is certainly of a nuptial character, and is seen in its greatest perfection only when the male stock-dove courts the female. This he does by either flying or walking up to her and bowing solemnly till his breast touches the ground, his tail going up at the same time to an even more than corresponding height, though with an action less solemn. The tail in its ascent is beautifully fanned, but it is not spread out flat like a fan, but arched, which adds to the beauty of its appearance. As it is brought down it closes again, but, should the bow be followed up, it is instantly again fanned out and sweeps the ground, as its owner, now risen from his prostrate attitude, with head erect and throat swelled, makes a little rush towards the object of his desires. The preliminary bow, however, is more usually followed by another, or by two or three others, each one being a distinct and separate affair, the bird remaining with his head sunk and tail raised and fanned for some seconds before rising to repeat. Thus it is not like two or three little bobs—which is the manner of wooing pursued by the turtle-dove— but there is one set bow, to which but one elevation and depression of the tail belongs, and the offerer of it must not only regain his normal upright attitude, but remain in it for a perceptible period before making another. This bow, therefore, is of the most impressive and even solemn nature, and expresses, as much as anything in dumb show can express, "Madam, I am your most devoted."

I believe—but I am not sure, and quite ready to be corrected—that the stock-dove's bow is either a silent one, or, at least, that the note uttered is subdued—the latter seems the more probable. At any rate, I was never able to catch it, either when watching on the warrens at a greater or less distance, or when not so far, amongst trees—for the stock-dove woos also amongst the leafy woods, as does the wood-pigeon, of which it is a smaller replica, but without the ring. "The male wood-pigeon, when courting, bows to the female lengthways along the branch on which he is sitting, elevating his tail at the same time, in just the same way as does the stock-dove. As he does so, he says 'coo-oo-oo,' the last syllable being long drawn out, and having a very intense expression, with a rise in the tone of it, sometimes almost to the extent of becoming a soft shrillness. Having delivered himself of this long 'coo-oo-oo,' he says several times together in an undertone, and very quickly, 'coo, coo, coo coo,' or 'coo, coo, coo, coo, coo, coo, coo,' after which, rising, and then bowing again, he recommences with the long-drawn, impassioned 'coo-oo-oo,' as before. All this he repeats several times, the number, probably, depending on whether the female bird stays to hear his addresses or, as is usual in the contrary, flies away. If she admits them pairing may take place, and at the conclusion of it both birds utter a peculiar, low, deep, and very raucous note which I have heard on this occasion, but on no other."

If the courting of the female stock-dove by the male whilst on the ground, or amongst the branches of a tree, is of a somewhat heavy nature—more pompous than beautiful—as is, I think, the case, it is lightened in the most graceful manner by the aerial intermezzos—the broidery of the theme—which charmingly relieve and set it off; for often, "after bowing and walking together a little, near, but not touching—a Hermia and Lysander distance—both rise, both mount, attain a height, then pause, and, as from the summit of some lofty precipice, descend on outspread joy-wings in a very music of motion. It is pretty, too, to watch two of them flying together and then alighting, when one instantly bows before the other with empressé mien. Before, you have not known which was which, or who was escorting the other. Now you feel sure that it is he—the empressé, the pompously bowing bird—who has taken her—the retiring, the coy one—for a little fly." For though it is undoubted that the female stock-dove bows to the male, yet, in courting, it is the male, I believe, who commences and carries it to a fine art.

There are no birds surely—or, at least, not many—who can sport more gracefully in the air than these. "One is sitting and cooing almost in a rabbit-burrow, and so close to a rabbit there that it looks like a little call. Sure enough, too, after a while, the bird, who, of course, is the visitor, rises—but into the air sans ceremonie—and makes as though to fly away. But having gone only a little distance, with quick strokes of the wings, it rests upon their expanded surface, and, in a lovely easy sweep, sails round again in the direction from whence it started. It passes beyond the place, the wings now again pulsating, then makes another wide sweep of grace and comes down near where it was before. In a little it again rises, again sweeps and circles, and again descends in the neighbourhood. Another now appears, flying towards it, and as it passes over where the first is sitting, this one rises into the air to meet it. They approach, glide from each other, again approach, and thus alternately widening and narrowing the distance between them, one at length goes down, the other passing on to alight, at last, at that distance which the etiquette of the affair prescribes. This circling flight on swiftly resting wings is most beautiful. The pausing sweep, the lazy onwardness, the marriage, as it were, of rest and speed is a delicious thing, another sense, a delicate purged voluptuousness, a very banquet to the eye." Such beauty-flights are almost always in the early morning, when appreciative persons are mostly in bed, seen only by the dull eye of some warrener walking to find and kill the beasts that have lain tortured in his traps all night, exciting (if any) but a murderous thought at the time, with the after-reflection, "If I'd a had a gun now"

Stock-doves, as is well known, often choose rabbit-burrows to lay their eggs in, and, having regard to their powers of flight and arborial aptitudes, it might be thought that but for the rabbits they would never be seen on these open, sandy tracts, the abode of the peewit, stone-curlew, ringed plover, red-legged partridge, and other such waste-haunting species. But the nesting habits of a bird must follow its general ones almost necessarily in the first instance, and though there are many apparently striking instances to the contrary, they are probably to be explained by the former having remained fixed whilst the latter have changed. No doubt, therefore, the stock-dove began to spend much of its time on the ground before it thought of laying its eggs there, and of the facilities offered by rabbit-holes for so doing. That the habits as well as the organisms of all living creatures are in a more or less plastic and fluctuating state is, I believe, a conclusion come to by Darwin, and it agrees entirely with the little I have been able to observe in regard to birds. I have seen the robin redbreast become a wagtail or stilt-walker, the starling a wood-pecker or fly-catcher, the tree-creeper also a fly-catcher, the wren an accomplished tree-creeper, the moor-hen a partridge or plover, and so on, and so on, all such instances having been noted down by me at the time. Most birds are ready to vary their habits suddenly and de novo if they can get a little profit on the transaction, and the extent to which they have varied gradually in a long course of time and under changed conditions is, of course, a commonplace after Darwin. The wood-pigeon has not yet begun to lay its eggs in rabbit-holes or anywhere but in trees and bushes, but that it may some day do so is not improbable, for it comes down sometimes, though not very frequently, on the same sandy wastes that are loved by the stock-dove, and here, like him, the male will court the female as though on the familiar bough.[3] When I have seen him courting her thus on the ground, the low bow which he makes her has been prefaced by one or more curious hops, which I have not seen in the stock-dove's courting. They look curious because they are so out of character, hopping being, as far as I know, a mode of progression foreign to all the columbidæ. Whether the wood-pigeon hops upon any other occasion I cannot be sure. If he does not—and it is certainly not his usual habit—his adoption of it here may be looked upon as a purely nuptial antic. In this the lark, which is also a stepping and not a hopping bird, keeps him company, as would the cormorant, were it not that he hops often as a matter of convenience. Larks I have not seen hop in everyday life, though sometimes I have thought that they did when running quickly over ploughed land in winter, as starlings often do when they break from a run which has become too quick for them into a running hop. But I came to the conclusion that this was only apparent, and due to their up and down motion over the clods of earth. A hop is quite foreign to the lark's disposition, yet, when courting, "the male bird advances upon the female with wings drooped, crest and tail raised, and with a series of impressive hops." The hop of the wood-pigeon, under similar circumstances, is of a heavy and deliberate nature, as might be expected his build and size, and has the same set and formal from character as the bow which immediately follows it.

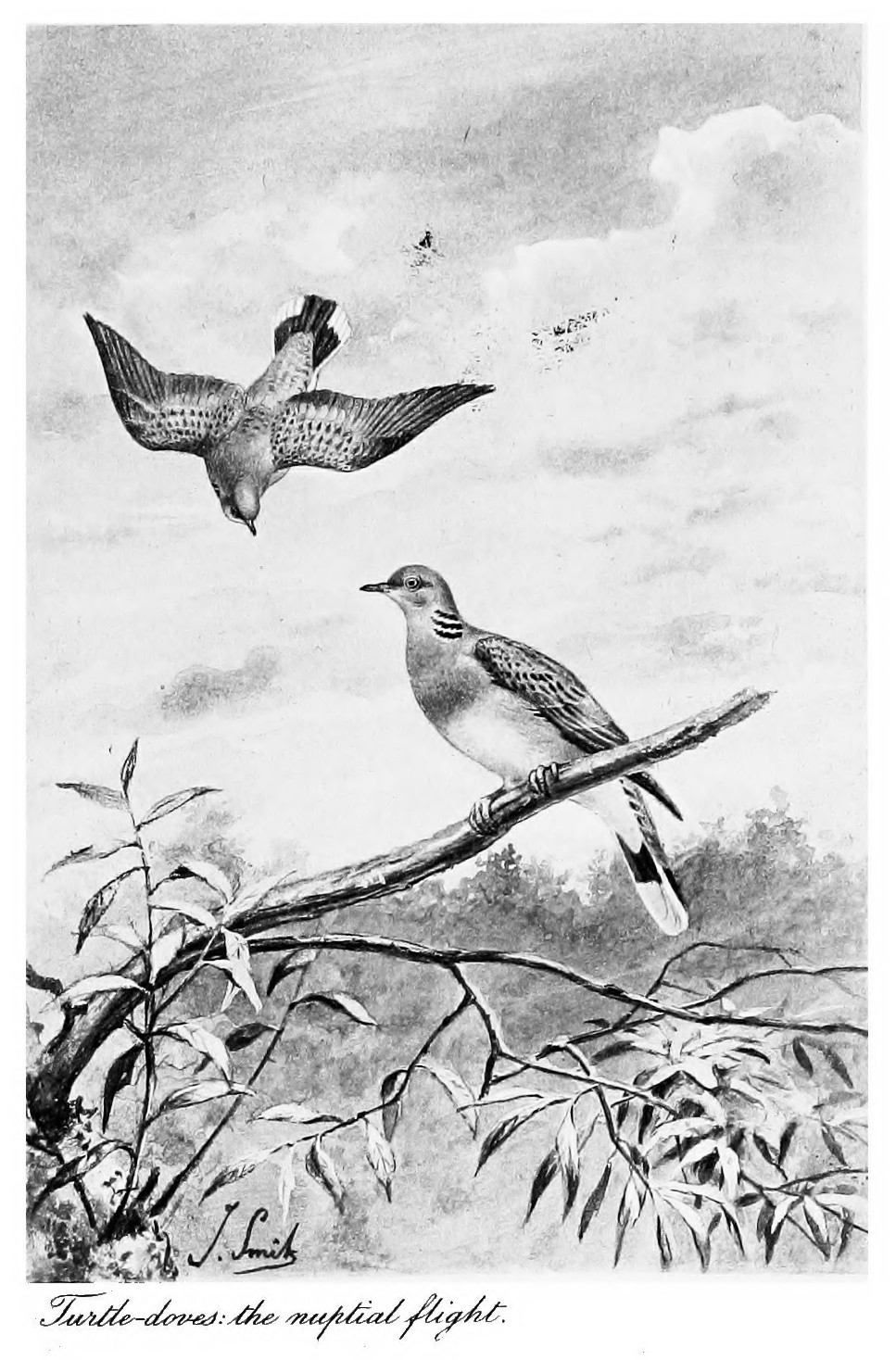

The turtle-dove bows too, in courtship, but it is a series of quick little bows, or, rather bobs, which he makes to his fiancée instead of one or more slower and much more imposing ones. Essentially, however, it is the same thing. The pace has been quickened and the interval lessened, whilst, to allow of the increased speed, the bow itself has been shorn of much of its pomp and circumstance, so that it has become, as I say, a mere bob. The turtle-dove may perform some half-dozen or more of these bobs, taking less time, perhaps, to get through them than do his larger relatives to achieve one of their solemn and formal bows. Still he is pompous too, he bends down low at the shrine, and though each little bob may not be much in itself, yet, when thus strung together, the display as a whole is equal to the other two.

All the time he is thus bowing or bobbing the turtle-dove utters a deep, rolling, musical note which is continuous (or sounds so), and does not cease till he has got back into his more everyday attitude. The hen looks sometimes surprised, sometimes as though she had expected it, and sometimes, I think,—but of this I am not quite positive—she will return the little series of musical bobs. This is in tree-land; but I have seen the turtle-dove court on the ground, and he then, between his bobbings, made a curious dancing step towards the female, who retired and gave her final answer by flying away. But, besides this, these birds have another and most charming nuptial disportment. Sitting a deux in some high tree, one of them will every now and again fly out of it, mount upwards, make one or two circling sweeps around and above it, then, after remaining poised for some seconds, descend on spread wings in the most graceful manner, alighting on the same branch beside the waiting partner. This is a beautiful thing to see, and especially in the early fresh morning of a clear, lovely day. It seems then as if the bird kept flying up to greet "the early rising sun," or as rejoicing in the beauty of all things. These are the coquetries, the prettinesses of loving couples, as to which—on one side at least—what has not been said by the writers of our clumsy race! But "if the lions were sculptors"—How might a bird novelist expatiate!Not less beautiful is the nuptial flight of the wood-pigeon. Of this, the clapping of the wings above the back is the most salient feature, a sound which is never heard during the winter or after the breeding-season is fairly over. "In full flight, the bird smites its wings two or three times smartly together above the back, then, holding them extended and motionless, it seems to pause for one instant—if there can be pause in swiftest motion—before sinking and then rising and sinking again, as does a wave, or as though it rested on an aerial switchback. Then continuing his flight—recommencing, that is to say, the strokes of his wings—he may do the same when he has gone a few air-fields farther, and so "pass in music out of sight." Sometimes there will be only a single clap of the wings instead of two or three,[4] but always it is made just before the still-spreading of them, and the hanging pause in the air; for let the speed be never so great—and it hardly seems possible that it could be checked so suddenly, and why should the bird wish to check it?—yet the effect upon the eye of the wings extended and motionless after they have been pulsating so rapidly is as of a pause. This pause, or rather this rest-in-speed, as the bird, renouncing all effort, is carried swiftly and placidly onwards in a curve of the extremest beauty has a delicious effect upon one. One's spirit goes out until one seems to be with the bird oneself, hanging and sweeping as it does. Yet in this glory of motion it will often be shot by beings, in all grace and beauty and poetry of life, how infinitely its inferiors! This makes me think of Darwin's comment upon Bate's account of a humming-bird caught and killed by a huge Brazilian spider, wherein the destroyer and the victim—"one, perhaps, the loveliest, the other the most hideous in the scale of creation"[5]—are contrasted. Spiders, too, had they their Phidiases, might be idealised and made to look quite beautiful in marble, even perhaps to our eyes (what cannot genius do?) whilst to their own, of course, the spider form would be "the spider form divine."

Wood-pigeons will also fly circling about above the trees in which they have been sitting, in rapid pursuit of each other, and whilst doing so, one or other of them may be heard to make a very pronounced swishing or beating sound with the wings, reminding one of the peewit, nightjar, and a great many other birds. Of instrumental music produced during flight, the snipe is a familiar example. Here, however, the very peculiar and highly specialised sound known as bleating or drumming is produced, not by the feathers of the wing, but by those of the tail, which have been specially modified, as we may suppose (those, at least, of us who are believers in that force), by a process of musical sexual selection. To quote Darwin:

"No one was able to explain the cause until Mr Meves observed that on each side of the tail the outer feathers are peculiarly formed, having a stiff sabre-shaped shaft with the oblique barbs of unusual length, the outer webs being strongly bound together. He found that by blowing on these feathers, or by fastening them to a long thin stick and waving them rapidly through the air, he could reproduce the drumming noise made by the living bird. Both sexes are furnished with these feathers, but they are generally larger in the male than in the female, and emit a deeper note."

The possibility of reproducing the sound in the manner described seems conclusive as to the cause of it. Otherwise I should have come to the conclusion, by watching the bird, that the wings and not the tail were the agency employed.

"I have just been watching for some time a snipe continually coursing through the air and making, at intervals, the well-known drumming or bleating sound,—bleating certainly seems to me the word which best expresses its quality. The wings are constantly and quickly quivered, not only when the bird rises or flies straight forward, but also during its swift oblique descents, when one might expect that they would be held rigid in the ordinary manner. From each sweep down the bird rises and beats again upwards, but when the flight has been continued long enough the wings are pressed to the sides as the plunge to earth is made, which is also one way in which the lark descends. It is during these downward flights—but not during the descent to earth—that the sound strikes the ear. A second bird flies, to my surprise and interest, quite differently. After scudding about for some little time in a devious side-to-side pathway, less up and down, as it seems to me, than the other, it suddenly tilts itself sideways, or almost sideways—one wing pointing skywards, the other earthwards—and makes a rapid swoop down, with the wings not beating. I watch it doing this time after time, both with the naked eye and through the glasses, and each time that the swoop is made no bleating or other sound accompanies it: the flight is noiseless, like that of an ordinary bird. Two other snipes are now flying about in this latter way and chasing each other. At first—and this included a great many sweeps down—I heard no sound. Afterwards I thought I heard it faintly sometimes, but could not be sure that it was not made by another bird—a frequent difficulty in watching snipe." Again, "A snipe is standing alone 'in the melancholy marshes,' quite still, and uttering the creaky, sea-sawey note. I can see the two long mandibles of the beak dividing slightly and again closing. The note is now thin and subdued, but, the bird taking flight suddenly, it becomes much accentuated. It joins two other birds in the air, and all three now sport and pursue each other about, constantly uttering this cry, but bleating only occasionally. I am lying flat on the ground, and they often fly close about and over me, the light, too, being good, it being all before 5.40, and not much after 5, perhaps, when it commenced (this was April 4th). I note that they often descend through the air without vibrating the wings, and there is then no bleating sound—this whilst quite close. I think—but am not yet quite sure—that they sometimes descend in this way uttering the cry. When they bleat, however, there is never the cry at the same time. It is impossible to tell when these birds are going to alight, as they often descend in the manner that they use when alighting, but, when almost down, skim a little just over the ground, and, rising again, continue their flight as before. Yet that they have had it in their mind to alight I feel sure, for they always do so with that particular action."

Since, then, the snipe has two ways of making his rapid descents through the air, in one of which he quivers his wings and in the other not, and since, on the latter occasion, the bleat is not heard or, if heard, only faintly, it would be natural to suppose that the sound—if not vocal—was produced by the rapidly vibrating feathers of the wing when in swift downward motion rather than by those of the tail, which should not, one would think, be affected by the difference. Also the fact of the vocal note not being uttered at the same time as the bleat might make one think that this, too, was vocal. Such arguments, however, would be at best but "poor seemings and thin likelihoods"—the last one, I believe, not supported by what we know (at least I cannot at the moment think of a bird that produces vocal and instrumental music at the same time). If the sound can really be reproduced by waving the modified feathers of the tail, then this is a demonstration.[6]

Snipe, as already observed, descend to the ground in order to alight upon it in a manner quite different to the oblique downward-shooting sweeps, with wings extended, whether vibrating or not, as practised in ordinary nuptial flight. There are three ways, possibly more; but three I have seen. In the first the bird shoots gracefully down, with the wings pressed to the sides, as already described. In the second the wings are raised straight, or almost straight, above the back, and this gives, perhaps, a still more graceful appearance. The third way is not nearly so usual a one as the other two—in fact, I only recall having seen it once. In this the wings are but half spread (whilst held in the ordinary manner) and motionless, and the bird descends in several sweeps to one side or the other, something after the manner in which a kite comes to the ground. No sound attends any of these forms of descent.

The cry of the snipe which I have alluded to, is of a curious nature, something like the word "chack-wood, chack-wood, chack-wood, chack-wood," constantly repeated, and having a regular rise and fall in it, which is why I call it a "see-saw note." Sometimes, when the bird is a little way off, it sounds very much like a swishing of the wings; but when these are really swished, as they often are—purposely, I believe, and as a nuptial performance—the difference is at once apparent. "Two snipes will often fly chasing each other, uttering this note, and making from time to time the loud swishing with the wings. Often, too, there will be a short, harsh cry—harsh, but with that wild, loved harshness that lives in the notes of birds that haunt the waste—which is instantly followed by a swishing of the wings, making quite a music in the air. When at its loudest and harshest, this cry, which then becomes a scream, is quite an extraordinary sound, having a mewing intonation in it suggesting a cat as the performer. Yet it is nothing so extraordinary as some notes of the snipe which I have heard, mostly during the winter, and which are indeed—at least they have struck me as being so—amongst the most wonderful that ever issued from the throat of bird. I will recur to them again when I come to the moor-hen (for it was in his company I heard them), a bird that is itself as a whole orchestra of peculiar brazen instruments. These wild cries and screams blend harmoniously with the curious, monotonous, yet musical bleating, and come finely out of the gloom of the evening thickening into night, as it descends over the wide expanse of the fenlands. Best heard then—and there: the darkening sky, the wide and wind-swept waste of coarse tufted grass, amongst which brown dock-stalks stand tall-ly and thinly, the long, raised bank with its thin belt of reeds beyond, emphasising rather than relieving the flatness, the lonely thorn-bush, the stunted willow or two, the black line of alders marking the course of the sluggish river, the wind, the sad whispered music in the grasses, the wilder music in the air, the aloneness, the drearness—such voices fit such scenes."

The male and female snipe both bleat, but the feathers in the tail which produce the sound are less modified in the female, and the sound which they produce is said to be different in consequence. That there must be a difference would seem to follow of necessity; but, according to my own experience, it requires a nice ear to distinguish the bleating of the one sex from that of the other. There is, indeed, some slight difference in the sound made by each individual snipe, but I only once remember hearing one bleating with a markedly different tone. Here the sound had a lower, softer, and deeper intonation, and was, to my mind, a more musical sound altogether. When heard just before or after the bleat of another snipe the difference was very marked, but I considered it to be rather an individual than a sexual distinction, for I do not know that there is any reason to suppose that the female snipe bleats less frequently than the male except when she is sitting on her eggs.

Snipe, when bleating, fly round and round in a wide irregular circle, and for a long time one will not over-step the invisible boundary so as to encroach upon the domain of the other. It seems—but the illusion will be broken after a time—as though each bird had his allotment in the fields of air and knew that he would be guilty of a rudeness in entering that of another. Thus, though three or four of them may be flying and bleating in the neighbourhood, it is often difificult to watch more than one at a time with anything like closeness of observation, a difficulty which is often increased by the failing light; for, in my own experience, snipe bleat best either in the early—though not very early—morning, or when evening has begun to close in. To follow their wide, swift, eccentric circle of flight one must keep turning round on a fixed point, and this, amidst swamp and grass-tufts, is difficult to do without losing one's balance. Yet still one watches and turns and strains one's eyes into the darkness, unable to go, for one loves to see that small, swift, vocal shadow appearing out of the great, still, silent ones and disappearing, again, into them. When thus disporting, each within its own charmed circle, the downward rush and bleat of one snipe will often for a long time immediately precede or follow that of another, bleat answering to bleat, till at length the duet is broken and complicated by a third intermingling voice. At last a bird, trampling on etiquette, will flit into the circle of the one you are watching, and the two, excitedly pursuing each other with "chack-wood, chack-wood," or, with the harsh, wild scream and loud swish of pinions, will speed off and vanish together.

No doubt the male snipes bleat against each other in rivalry, but it would also seem (a sentence, I confess, which I never use when I have an undoubted instance to give) that the male and female bleat to one another connubially, or in a lover-like manner. Here, however, is an instance (as I translate it) of the one bleating whilst the other sits listening and responding vocally on the ground.

"A snipe flies with a scream over the marshy meadows. As he passes one little swampy bit another snipe utters from out of it the see-sawey, 'chack-wood' note, in answer, as it appears, to the scream. The first snipe now flies round about over the meadows and land adjoining, bleating, whilst the other one in the grass continues to see-saw."

Many birds, as is well known, have the instinct, when suddenly discovered with their young ones, of tumbling over or fluttering along the ground as though they had sustained some injury which had rendered them unable to fly, so that the murderous or thievish longings of "the paragon of animals" being diverted from their progeny to themselves, the former may take thought and escape. The nightjar, partridge, and, especially, the wild-duck, are good instances of this, and in every case where I have come upon them under the requisite conditions they have never failed to show me their shrewd estimate of man's nature. With all these three birds, however, it has always been the presence of the young that has moved them to act in this manner, their conduct during incubation being quite different. The instance which I am now going to bring forward with regard to the snipe has this peculiarity, if it be one, that the bird was hatching her eggs at the time and was still engaged in doing so a few days afterwards, proving that the young were not just on the point of coming out on the occasion when she was first disturbed. As I noted all down the instant after its occurrence, the reader may rely upon having here just exactly what this snipe did.

"This morning a snipe flew out of some long reedy grass within a few feet of me, and almost instantly taking the ground again—but now on the smooth, green meadow—spun round over it, now here, now there, its long bill lying along the ground as though it were the pivot on which it turned, and uttering loud cries all the while. Having done this for a minute or so, it lay, or rather crouched, quite still on the ground, its head and beak lying along it, its neck outstretched, its legs bent under it, with the body rising gradually, till the posterior part, with the tail, which it kept fanned out, was right in the air. And in this strange position it kept uttering a long, low, hoarse note, which, together with its whole demeanour, seemed to betoken great distress. It remained thus for some minutes before flying away, during which time I stood still, watching it closely, and when it was gone, soon found the nest, with four eggs in it, in the grass-tuft from which it had flown. Its action whilst spinning over the ground was very like that of the nightjar when put up from her young ones."

It is to be noted here that this snipe flew a very little way from the nest, and when on the ground did not travel over it to any extent, but only in a small circle just at first, after which it kept in one place. The Arctic skua (Richardson's skua, as some call it, but I hate such appropriative titles—as though a species could be any man's property!) behaves in the same kind of way, for, lying along on its breast, with its wings spread out and beating the ground, it utters plaintive little pitiful cries, keeping always in the same, or nearly the same, spot. This has, of course, the effect of drawing one's attention to the bird, and away from the eggs or young (whether it acts thus in regard to both I am not quite sure, but believe that it does), but the effect produced on one—though here, of course, as throughout, I only speak for myself—is that the bird is in great mental distress—prostrated as it were—rather than acting with any conscious "intent to deceive." The same is the case with the nightjar, whose sudden spinning about over the ground in a manner much more resembling a maimed bluebottle or cockchafer than a bird, seems to proceed from some violent nervous shock or mental disturbance. The same, too, though in a lesser degree, may be said of the partridge, and in all cases it is obvious that the bird is very much excited and ausser sich.

Darwin, if I remember rightly,[7] found it difficult to believe that birds, when they thus distract our attention from their young to themselves, do so with a full consciousness of what they are doing and why they are doing it. When the female wild-duck, however, acts in this manner, it is difficult, I think, to escape from this conclusion. She flaps for a long way over the surface of the water, pausing every now and again and waiting, as though to see the effect of her ruse, and continuing her tactics as soon as you get up to her. Having thus led you a long distance away, she rises, and leaving the river, flies in an extended circle, which will ultimately bring her back to it by the other bank when you are well out of the way. The chicks, meanwhile, have (of course) scuttled in amongst the reeds and rushes, though they often take some little while to conceal themselves. She acts thus on a river or broad stretch of water, which enables her to keep you in sight for some time. But it is obvious that if you come upon her with her family in a very narrow and sharply winding stream, the first bend of it will hide you from her, and she would then, assuming that she is acting intelligently, have all the agony of mind of not knowing whether her plan was succeeding or not. It was in such a situation that I met her only last spring, and to my surprise—and indeed, admiration—instead of flapping along the water as I have always known her to do before in such a ' contretemps, she instantly flew out on to the opposite bank, and began to flap and struggle along the flat marshy meadow-land, of course in full view. I crossed the stream and pursued her, allowing her to "fool me to the top of my bent," and this she appeared to me to do, or to think she was doing, on much the same kind of indicia as one would go by in the case of a man. Now, unless this bird had wished to keep me in view, and thus judge of the effect of her stratagem, or unless she feared that "out of sight" would be "out of mind" with regard to herself (but this would be to credit her with yet greater powers of reflection), why should she have left the water, the element in which she usually and most naturally performs these actions, to modify them on the land? Yet to suppose that it has ever occurred suddenly, and as a new idea, to any bird to act a pious fraud of this kind, would be to suppose wonders, and also to be unevolutionary (almost as serious a matter nowadays as to be un-English).

But may we not think that an act, which in its origin has been of a nervous and, as it were, pathological character, has become, in time, blended with intelligence, and that natural selection has not only picked out those birds who best performed a mechanical action—which, though it sprung merely from mental disturbance, was yet of a beneficial nature—but also those whose intelligence began after a time to enable them to see whereto such action tended, and thus consciously to guide and improve it? There is evidence, I believe—though neither space nor the nature of this slight work will allow me to go into it—that such abnormal mental states as of old inspired "the pale-eyed priest from the prophetic cell," and to-day influence priests or medicine-men amongst savages (to go no farther), can be, and are, combined with ordinary shrewd intelligence; nor does it seem too much to suppose that a bird that was always seeing the effect of what it did when it, as it were, fell into hysterics, should have come in time to reckon upon the hysterics, to know what they were good for, and even to some extent to direct them—as a great actor in an emotional scene must govern himself in the main, though, probably, a great deal of the gesture, action, and facial expression is unconsciously and spontaneously performed.

Now, if we assume that these ruses employed by birds for the protection of their young—as in the case of the wild-duck—have commenced in purely involuntary movements, without any proposed object, the instance here given of the snipe may perhaps throw some light upon their origin. A bird, whilst incubating, and thus, hour after hour, doing violence to its active and energetic disposition, is under the influence of a strong force in opposition to and overcoming the forces which usually govern it. Its mental state may be supposed to be a highly-wrought and tense one, and it therefore does not seem surprising that some sudden surprise and startle at such a time, by rousing a force opposite to that under the control of which it then is, and producing thereby a violent conflict, should throw it off its mental balance and so produce something in the nature of hysteria or convulsions. But let this once take place with anything like frequency in the case of any bird, and natural selection will begin to act. As the eggs of a bird are stationary, and do not run away or seek shelter whilst the parent bird is thus behaving in their neighbourhood, it would, on the whole, be better for it to sit close or to fly away in an ordinary and non-betraying manner. Allowing this, then, as the eggs of a bird would be less exposed to danger the less often the sitting bird went off them in this way, might not natural selection keep throwing the impulse to do so farther and farther backwards till after the incubatory process was completed? Then the tendency would be encouraged—at least in the case of birds whose young can early get about—for, as a rule, such antics would shield them better than sitting still. The young would generally be in several places—giving as many chances of discovery—and, on account of the suddenness of the surprise, would often be running or otherwise exposing themselves. Take, for instance, the case of the wild-duck, where I have always found the brood a most conspicuous object at first, and taking some time, even on reedy rivers, to get into concealment.

And I can see no reason why an aiding intelligence in the performance of such movements should not be selected pari passu with the movements themselves, though of a nervous and, originally, purely automatic character. Natural selection would, in this way, develop a special intelligence in the performance of some special actions, out of proportion to the general intelligence of the creature performing them, though, no doubt, this also would tend to be thereby enlarged. And this is what, in fact, we often do see or seem to see. I may add that when, a few days afterwards, I again approached this same nest the bird went off it without any performance of the sort. This, if we could be sure that it was the same bird, would seem to show that the habit was in an unfixed and fluctuating condition. On the other hand, a bird that acts thus in the case of its young, would, I think, always act so.

Perhaps it may be wondered why I have not included the peewit in the list of birds which employ, or appear to employ, a ruse in favour of their young ones, since this bird is always given as the stock instance of it. The reason is, that whilst the birds I mentioned have always, in my experience, gone off, so to speak, like clock-work, when the occasion for it arrived, I have never known a peewit to do so, though I have probably disturbed as many scores—perhaps hundreds—of them, under the requisite conditions, as I have units of the others. I have also inquired of keepers and warreners, and found their experience to tally with mine. They have spoken of the cock bird "leading you astray" aerially, whilst the hen sits on the nest, and of both of them flying, with screams, close about your head when the young are out, which statements I have often verified. But they have never professed to have seen a peewit flapping over the ground as with a broken wing, in the way it is so constantly said to do. I cannot, therefore, but think that, by some chance or other, an action common to many birds has been particularly, and yet wrongly, ascribed to the peewit. As it seems to me, this is just one of those cases where negative evidence is almost as strong as affirmative, and though, of course, quite ready to accept any properly witnessed instance of the peewit's acting in this way, I cannot but conclude that it does so very rarely indeed.

- ↑ But I did not see what they were doing before they rose.

- ↑ With this suggestion, however, that fighting may be blended with sexual display in the combats of male birds owing to association of ideas, for rivalry is the main cause of such combats.

- ↑ The same remark applies to the turtle-dove.

- ↑ Sometimes, too, not any, the flight being the same.

- ↑ I quote from memory.

- ↑ I have lately observed that when the snipe descends with quivering wings, some outer feathers of the tail on each side are shot out from it in a most noticeable manner, making—or looking like—two little curved tufts. They are not seen before, which seems to me strong evidence. The tail itself is fanned.

- ↑ But I have not been able to find the passage, so may be mistaken.