Bismarck and the Foundation of the German Empire/Chapter 16

CHAPTER XVI.

THE TRIPLE ALLIANCE AND ECONOMIC REFORM.

1878-1887.

THE year 1878 forms a turning-point both in internal and in external politics. Up to this year Prussia has been allied with the two Eastern monarchies; the Empire has been governed by the help of the National Liberal party; the chief enemy has been the Clericals. The traditions of the time before the war are still maintained. After this year the understanding with Russia breaks down; instead of it the peace of Europe is preserved by the Triple Alliance with Austria and Italy. In internal affairs the change is even more marked; the rising power of the Socialists is the enemy to be fought against; for this conflict, peace has to be made with the Catholics—the May laws are modified or repealed. The alliance with Liberalism breaks down, and the efforts of the Government are devoted to a far-reaching scheme of financial reform and social legislation.

When, in April, 1877, the Emperor refused to accept Bismarck's resignation, the whole country applauded the decision. In the Reichstag a great demonstration was made of confidence in the Chancellor. Everyone felt that he could not be spared at a time when the complications in the East were bringing new dangers upon Europe, and in the seclusion of Varzin he did not cease during the next months to direct the foreign policy of the Empire. He was able with the other Governments of Europe to prevent the spread of hostilities from Turkey to the rest of Europe, and when the next year the English Government refused its assent to the provisional peace of San Stefano, it was the unanimous desire of all the other States that the settlement of Turkey should be submitted to a Congress at Berlin over which he should preside. It was the culmination of his public career; it was the recognition by Europe in the most impressive way of his primacy among living statesmen. In his management of the Congress he answered to the expectations formed of him. "We do not wish to go," he had said, "the way of Napoleon; we do not desire to be the arbitrators or schoolmasters of Europe. We do not wish to force our policy on other States by appealing to the strength of our army. I look on our task as a more useful though a humbler one; it is enough if we can be an honest broker." He succeeded in the task he had set before himself, and in reconciling the apparently incompatible desires of England and Russia. Again and again when the Congress seemed about to break up without result he made himself the spokesman of Russian wishes, and conveyed them to Lord Beaconsfield, the English plenipotentiary.

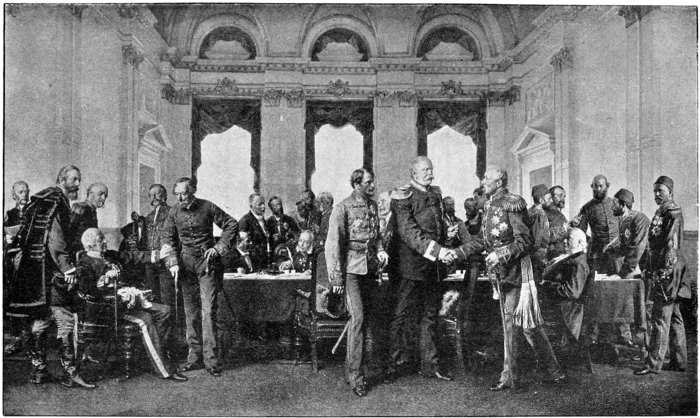

THE CONGRESS OF BERLIN, 1878.

FROM A PAINTING BY ANTON VON WERNER.

During this crisis in foreign affairs Bismarck was occupied by another, which threatened to be equally serious, in home politics. In the spring of 1878 an attempt was made on the life of the Emperor; a young man, named Hobel, a shoemaker's apprentice, shot at him in the streets of Berlin, fortunately without result. The attempt naturally created intense indignation throughout the country. This was increased when it became known that he had been to some extent connected with the Socialist party, and it seemed as though the motives of the crime were supplied by the violent speeches made at Socialist gatherings. Bismarck had long regarded the growth of Socialism with concern. He determined to use this opportunity to crush it. He at once brought into the Bundesrath a very severe law, forbidding all Socialist agitation and propaganda. He succeeded in passing it through the Council, but it was thrown out in the Reichstag by a very large majority. No one voted for it except the Conservatives. The law indeed was so drawn up that one does not see how anyone could have voted for it; the first clause began, "Printed writings and unions which follow the aims of Social Democracy may be forbidden by the Federal Council," but, as was pointed out, among the aims of Social Democracy were many which were good in themselves, and many others which, though they might be considered harmful by other parties, were at least legitimate. Directly afterwards the Reichstag was prorogued. Ten days later, another attempt was made on the Emperor's life; this time a man of the name of Nobeling (an educated man who had studied at the University) shot at him while driving in the Unter den Linden, and wounded him severely in the head and arms with large shot. The Emperor was driven home to his palace almost unconscious, and for some time his life was in danger. This second attempt in so short a time on the life of a man almost eighty years of age, so universally loved and respected, who had conferred such benefits on his country, naturally aroused a storm of indignation. When Bismarck received the news his first words were, "Now the Reichstag must be dissolved." This was done; the general elections took place while the excitement was still hot, and of course resulted in a great loss to those parties—especially the National Liberals—who had voted against the Socialist law; the Centre alone retained its numbers. Before this new Parliament a fresh law was laid, drafted with much more skill. It absolutely forbade all speeches or writing in favour of plans for overthrowing the order of society, or directed against marriage and property. It enabled the Government to proclaim in all large towns a state of siege, and to expel from them by the mere decree of the police anyone suspected of Socialist agitation. The law, which was easily carried, was enforced with great severity; a state of siege was proclaimed in Berlin and many other places. Socialist papers, and even books, for instance the writings of Lassalle, were forbidden; they might not even be read in public libraries; and for the next twelve years the Socialist party had to carry on their propaganda by secret means.

This Socialist law is very disappointing; we find the Government again having recourse to the same means for checking and guiding opinion which Metternich had used fifty years before. Not indeed that the Socialists themselves had any ground for complaint; their avowed end was the overthrow of government and society; they professed to be at war with all established institutions; if they confined their efforts to legal measures and did not use violence, it was only because the time had not yet come. The men who avowed admiration for the Paris Commune, who were openly preparing for a revolution more complete than any which Europe had hitherto seen, could not complain if the Government, while there was yet time, used every means for crushing them. The mistake was in supposing that this measure would be successful. Bismarck would, indeed, had he been able, have made it far more severe; his own idea was that anyone who had been legally convicted of holding Socialist opinions should be deprived of the franchise and excluded from the Parliament. What a misunderstanding does this shew of the whole object and nature of representative institutions! It had been decided that in Germany Parliament was not to govern; what then was its function except to display the opinions of the people? If, as was the case, so large a proportion of the German nation belonged to a party of discontent, then it was above all desirable that their wishes and desires should have open expression, and be discussed where they could be overthrown. The Government had enormous means of influencing opinion. In the old days the men of letters had been on principle in opposition; now Germany was flooded by papers, books, and pamphlets, all devoted to the most extravagant praise of the new institutions. The excuse which was made for these laws was not a sufficient one. It is seldom necessary to meet political assassination by repressive measures, for they must always create a danger which they intend to avert. There was not the slightest ground for supposing that either Hobel or Nobeling had any confederates; there was no plot; it was but the wild and wicked action of an individual. It was as absurd to put a large party under police control for this reason as it was to punish Liberals for the action of Sand. And it was ineffective, as the events of the next years shewed; for the Socialist law did not spare Germany from the infection of outrage which in these years overran Europe.

The Socialist laws were soon followed by other proposals of a more useful kind, and now we come to one of the most remarkable episodes in Bismarck's career. He was over sixty years of age; his health was uncertain; he had long complained of the extreme toil and the constant annoyance which his public duties brought upon him. It might appear that he had finished his work, and, if he could not retire altogether, would give over the management of all internal affairs to others. That he would now take upon himself a whole new department of public duties, that he would after his prolonged absence appear again as leader and innovator in Parliamentary strife—this no one anticipated.

Up to the year 1876 he had taken little active part in finance; his energies had been entirely absorbed by foreign affairs and he had been content to adopt and support the measures recommended by his technical advisers. When he had interfered at all it had only been on those occasions when, as with regard to commercial treaties, the policy of his colleagues had impeded his own political objects. In 1864 he had been much annoyed because difference on commercial matters had interfered with the good understanding with Austria, which at that time he was trying to maintain. Since the foundation of the Empire almost the complete control over the commercial policy of the Empire had been entrusted to Delbrück, who held the very important post of President of the Imperial Chancery, and was treated by Bismarck with a deference and consideration which no other of his fellow-workers received, except Moltke and Roon. Delbrück was a confirmed Free-Trader, and the result was that, partly by commercial treaties, and partly by the abolition of customs dues, the tariff had been reduced and simplified. The years following the war had, however, not been altogether prosperous; a great outbreak of speculation was followed in 1873 by a serious commercial crisis. And since that year there had been a permanent decrease in the Imperial receipts. This was, for political reasons, a serious inconvenience. By the arrangement made in 1866 the proceeds of the customs and of the indirect taxation (with some exceptions) were paid into the Exchequer of the Federation, and afterwards of the Empire. If the receipts from these sources were not sufficient to meet the Imperial requirements, the deficit had to be made up by contributions paid (in proportion to their population) by the separate States. During later years these contributions had annually increased, and it is needless to point out that this was sufficient to make the relations of the State Governments to the central authorities disagreeable, and to cause some discontent with the new Constitution. This meant also an increase of the amount which had to be raised by direct taxation. Now Bismarck had always much disliked direct taxes; he had again and again pointed out that they were paid with great reluctance, and often fell with peculiar hardship on that very large class which could only just, by constant and assiduous labour, make an income sufficient for their needs. Worst of all was it when they were unable to pay even the few shillings required; they then had to undergo the hardship and disgrace of distraint, and see their furniture seized and sold by the tax-collectors. He had therefore always wished that the income derived from customs and indirect taxation should be increased so as by degrees to do away with the necessity for direct taxation, and if this could be done, then, instead of the States paying an annual contribution to the Empire, they would receive from the central Government pecuniary assistance.

The dislike of direct taxation is an essential part of Bismarck's reform; he especially disapproved of the Prussian system, the barbarous system, as he called it, according to which every man had to pay a small portion, it might be even a few groschen, in direct taxes.

"I ascribe," he said, "the large part of our emigration to the fact that the emigrant wishes to escape the direct pressure of the taxes and execution, and to go to a land where the klassensteuer does not exist, and where he will also have the pleasure of knowing that the produce of his labours will be protected against foreign interference."

His opinion cannot be called exaggerated if it is true that, as he stated, there were every year over a million executions involving the seizure and sale of household goods on account of arrears of taxation. It was not only the State taxes to which he objected; the local rates for municipal expenses, and especially for education, fell very heavily on the inhabitants of large cities such as Berlin. He intended to devote part of the money which was raised by indirect taxation to relieving the rates.

His first proposals for raising the money were of a very sweeping nature. He wished to introduce a State monopoly for the sale of tobacco, brandy, and beer. He entered into calculations by which he proved that were his policy adopted all direct taxation might be repealed, and he would have a large surplus for an object which he had very much at heart—the provision of old-age pensions. It was a method of legislation copied from that which prevails in France and Italy. He pointed out with perfect justice that the revenue raised in Germany from the consumption of tobacco was much smaller than it ought to be. The total sum gained by the State was not a tenth of that which was produced in England by the taxing of tobacco, but no one could maintain that smoking was more common in England than in Germany. In fact tobacco was less heavily taxed in Germany than in any other country in Europe.

In introducing a monopoly Bismarck intended and hoped not only to relieve the pressure of direct taxation,—though this would have been a change sufficient in its magnitude and importance for most men,—but proposed to use the very large sum which the Government would have at its disposal for the direct relief of the working classes. The Socialist law was not to go alone; he intended absolutely to stamp out this obnoxious agitation, but it was not from any indifference as to the condition of the working classes. From his earliest days he had been opposed to the Liberal doctrine of laissez-faire; it will be remembered how much he had disliked the bourgeois domination of the July Monarchy; as a young man he had tried to prevent the abolition of guilds. He considered that much of the distress and discontent arose from the unrestricted influence of capital. He was only acting in accordance with the oldest and best traditions of the Prussian Monarchy when he called in the power of the State to protect the poor. His plan was a very bold one; he wished to institute a fund from which there should be paid to every working man who was incapacitated by sickness, accident, or old age, a pension from the State. In his original plan he intended the working men should not be required to make any contribution themselves towards this fund. It was not to be made to appear to them as a new burden imposed on them by the State. The tobacco monopoly, he said, he looked on as "the patrimony of the disinherited."

He did not fear the charge of Socialism which might be brought against him; be defended himself by the provisions of the Prussian law. The Code of Frederick the Great contained the words:

"It is the duty of the State to provide for the sustenance and support of those of its citizens who cannot procure sustenance themselves"; and again, "work adapted to their strength and capacity shall be supplied to those who lack means and opportunity of earning a livelihood for themselves and those dependent on them."

In the most public way the new policy was introduced by an Imperial message, on November 17, 1881, in which the Emperor expressed his conviction that the social difficulties could not be healed simply by the repression of the exaggerations of Social Democracy, but at the same time the welfare of the workmen must be advanced. This new policy had the warm approval of both the Emperor and the Crown Prince; no one greeted more heartily the change than Windthorst.

"Allow me," he once said to Bismarck, "to speak openly: you have done me much evil in my life, but, as a German patriot, I must confess to you my gratitude that after all his political deeds you have persuaded our Imperial Master to turn to this path of Social Reform."

There were, he said, difficulties to be met; he approved of the end, but not of all the details,

"and," he continued, "something of the difficulty, if I may say so, you cause yourself. You are often too stormy for us; you are always coming with something new and we cannot always follow you in it, but you must not take that amiss. We are both old men and the Emperor is much older than we are, but we should like ourselves in our lifetime to see some of these reforms established. That I wish for all of us and for our German country, and we will do our best to help in it."

Opinions may differ as to the wisdom of Bismarck's social and financial policy; nobody can deny their admiration for the energy and patriotism which he displayed. It was no small thing for him, at his age, to come out of his comparative retirement to bring forward proposals which would be sure to excite the bitterest opposition of the men with whom he had been working, to embark again on a Parliamentary conflict as keen as any of those which had so taxed his energies in his younger years. Not content with inaugurating and suggesting these plans, he himself undertook the immediate execution of them. In addition to his other offices, in 1880 he undertook that of Minister of Trade in Prussia, for he found no one whom he could entirely trust to carry out his proposals. During the next years he again took a prominent part in the Parliamentary debates; day after day he attended to answer objections and to defend his measures in some of his ablest and longest speeches. By his proposals for a duty on corn he regained the support of most of the Conservatives, but in the Reichstag which was elected in 1884 he found himself opposed by a majority consisting of the Centre, Socialists, and Progressives. Many of the laws were rejected or amended, and it was not until 1890 that, in a modified form, the whole of the social legislation had been carried through.

For the monopoly he gained no support; scarcely a voice was raised in its favour, nor can we be surprised at this. It was a proposal very characteristic of his internal policy; he had a definite aim in view and at once took the shortest, boldest, and most direct road towards it, putting aside the thought of all further consequences. In this others could not follow him; quite apart from the difficulties of organisation and the unknown effect of the law on all those who gained their livelihood by the growth, preparation, and sale of tobacco, there was a deep feeling that it was not safe to entrust the Government with so enormous a power. Men did not wish to see so many thousands enrolled in the army of officials, already too great; they did not desire a new check on the freedom of life and occupation, nor that the Government should have the uncontrolled use of so great a sum of money. And then the use he proposed to make of the proceeds: if the calculations were correct, if the results were what he foretold, if from this monopoly they would be able to pay not only the chief expenses of the Government but also assign an old-age pension to every German workman who reached the age of seventy—what would this be except to make the great majority of the nation prospective pensioners of the State? With compulsory attendance at the State schools; with the State universities as the only entrance to public life and professions; when everyone for three years had to serve in the army; when so large a proportion of the population earned their livelihood in the railways, the post-office, the customs, the administration—the State had already a power and influence which many besides the Liberals regarded with alarm. What would it be when every working man looked forward to receiving, after his working days were over, a free gift from the Government? Could not this power be used for political measures also; could not it become a means for checking the freedom of opinions and even for interfering in the liberty of voting?

He had to raise the money he wanted in another way, and, in 1879, he began the great financial change that he had been meditating for three years; he threw all his vigour into overthrowing Free Trade and introducing a general system of Protection.

In this he was only doing what a large number of his countrymen desired. The results of Free Trade had not been satisfactory. In 1876 there was a great crisis in the iron trade; owing to overproduction there was a great fall of prices in England, and Germany was being flooded with English goods sold below cost price. Many factories had to be closed, owners were ruined, and men thrown out of work; it happened that, by a law passed in 1873, the last duty on imported iron would cease on the 31st of December, 1876. Many of the manufacturers and a large party in the Reichstag petitioned that the action of the law might at any rate be suspended. Free-Traders, however, still had a majority, for the greater portion of the National Liberals belonged to that school, and the law was carried out. It was, however, apparent that not only the iron but other industries were threatened. The building of railways in Russia would bring about an increased importation of Russian corn and threatened the prosperity, not only of the large proprietors, but also of the peasants. It had always been the wise policy of the Prussian Government to maintain and protect by legislation the peasants, who were considered the most important class in the State. Then the trade in Swedish wood threatened to interfere with the profits from the German forests, an industry so useful to the health of the country and the prosperity of the Government. But if Free Trade would injure the market for the natural products of the soil, it did not bring any compensating advantages by helping industry. Germany was flooded with English manufactures, so that even the home market was endangered, and every year it became more apparent that foreign markets were being closed. The sanguine expectations of the Free-Traders had not been realised; America, France, Russia, had high tariffs; German manufactured goods were excluded from these countries. What could they look forward to in the future but a ruined peasantry and the crippling of the iron and weaving industries? "I had the impression," said Bismarck, "that under Free Trade we were gradually bleeding to death."

He was probably much influenced in his new policy by Lothar Bucher, one of his private secretaries, who was constantly with him at Varzin. Bucher, who had been an extreme Radical, had, in 1849, been compelled to fly from the country and had lived many years in England. In 1865 he had entered Bismarck's service. He had acquired a peculiar enmity to the Cobden Club, and looked on that institution as the subtle instrument of a deep-laid plot to persuade other nations to adopt a policy which was entirely for the benefit of England. He drew attention to Cobden's words—"All we desire is the prosperity and greatness of England." We may in fact look on the Cobden Club and the principles it advocated from two points of view. Either they are, as Bucher maintained, simply English and their only result will be the prosperity of England, or they are merely one expression of a general form of thought which we know as Liberalism; it was an attempt to create cosmopolitan institutions and to induce German politicians to take their economic doctrines from England, just as a few years before they had taken their political theories. In either case these doctrines would be very distasteful to Bismarck, who disliked internationalism in finance as much as he did in constitutional law or Socialist propaganda.

Bismarck in adopting Protection was influenced, not by economic theory, but by the observation of facts. "All nations," he said, "which have Protective duties enjoy a certain prosperity; what great advantages has America reached since it threatened to reduce duties twice, five times, ten times as high as ours!" England alone clung to Free Trade, and why? Because she had grown so strong under the old system of Protection that she could now as a Hercules step down into the arena and challenge everyone to come into the lists. In the arena of commerce England was the strongest. This was why she advocated Free Trade, for Free Trade was really the right of the most powerful. English interests were furthered under the veil of the magic word Freedom, and by it German enthusiasts for liberty were enticed to bring about the ruin and exploitation of their own country.

If we look at the matter purely from the economic point of view, it is indeed difficult to see what benefits Germany would gain from a policy of Free Trade. It was a poor country; if it was to maintain itself in the modern rivalry of nations, it must become rich. It could only become rich through manufactures, and manufactures had no opportunity of growing unless they had some moderate protection from foreign competition.

The effect of Bismarck's attention to finance was not limited to these great reforms; he directed the whole power of the Government to the support of all forms of commercial enterprise and to the removal of all hindrances to the prosperity of the nation. To this task he devoted himself with the same courage and determination which he had formerly shewn in his diplomatic work.

One essential element in the commercial reform was the improvement of the railways. Bismarck's attention had long been directed to the inconveniences which arose from the number of private companies, whose duty it was to regard the dividends of the shareholders rather than the interests of the public. The existence of a monopoly of this kind in private hands seemed to him indefensible. His attention was especially directed to the injury done to trade by the differential rate imposed on goods traffic; on many lines it was the custom to charge lower rates on imported than on exported goods, and this naturally had a very bad effect on German manufactures. He would have liked to remedy all these deficiencies by making all railways the property of the Empire (we see again his masterful mind, which dislikes all compromise); in this, however, he was prevented by the opposition of the other States, who would not surrender the control of their own lines. In Prussia he was able to carry out this policy of purchase of all private lines by the State; by the time he laid down the Ministry of Commerce hardly any private companies remained. The acquisition of all the lines enabled the Government greatly to improve the communication, to lower fares, and to introduce through communications; all this of course greatly added to the commercial enterprise and therefore the wealth of the country.

He was now also able to give his encouragement and support to those Germans who for many years in countries beyond the sea had been attempting to lay the foundations for German commerce and even to acquire German colonies. Bismarck's attitude in this matter deserves careful attention. As early as 1874 he had been approached by German travellers to ask for the support of the Government in a plan for acquiring German colonies in South Africa. They pointed out that here was a country fitted by its climate for European occupation; the present inhabitants of a large portion of it, the Boers, were anxious to establish their independence of England and would welcome German support. It was only necessary to acquire a port, either at Santa Lucia or at Delagoa Bay, to receive a small subsidy from the Government, and then private enterprise would divert the stream of German emigration from North America to South Africa. Bismarck, though he gave a courteous hearing to this proposal, could not promise them assistance, for, as he said, the political situation was not favourable. He must foresee that an attempt to carry out this or similar plans would inevitably bring about very serious difficulties with England, and he had always been accustomed to attach much importance to his good understanding with the English Government. During the following years, however, the situation was much altered. First of all, great enterprise had been shewn by the German merchants and adventurers in different parts of the world, especially in Africa and in the Pacific. They, in those difficulties which will always occur when white traders settle in half-civilised lands, applied for support to the German Government, Bismarck, as he himself said, did not dare to refuse them this support.

"I approached the matter with some reluctance; I asked myself, how could I justify it, if I said to these enterprising men, over whose courage, enthusiasm, and vigour I have been heartily pleased: 'That is all very well, but the German Empire is not strong enough, it would attract the ill-will of other States,' I had not the courage as Chancellor to declare to them this bankruptcy of the German nation for transmarine enterprises."

It must, however, happen that wherever these German settlers went, they would be in the neighbourhood of some English colony, and however friendly were the relations of the Governments of the two Powers, disputes must occur in the outlying parts of the earth. In the first years of the Empire Bismarck had hoped that German traders would find sufficient protection from the English authorities, and anticipated their taking advantage of the full freedom of trade allowed in the British colonies; they would get all the advantages which would arise from establishing their own colonies, while the Government would be spared any additional responsibility. He professed, however, to have learnt by experience from the difficulties which came after the annexation of the Fiji Islands by Great Britain that this hope would not be fulfilled; he acknowledged the great friendliness of the Foreign Office, but complained that the Colonial Office regarded exclusively British interests. As a complaint coming from his mouth this arouses some amusement; the Colonial Office expressed itself satisfied to have received from so high an authority a testimonial to its efficiency which it had rarely gained from Englishmen.

The real change in the policy of the Empire must, however, be attributed not to any imaginary shortcomings of the English authorities; it was an inevitable result of the abandonment of the policy of Free Trade, and of the active support which the Government was now giving to all forms of commercial enterprise. It was shewn, first of all, in the grant of subsidies to mail steamers, which enabled German trade and German travellers henceforward to be carried by German ships; before they had depended entirely on English and French lines. It was not till 1884 that the Government saw its way to undertake protection of German colonists. They were enabled to do so by the great change which had taken place in the political situation. Up to this time Germany was powerless to help or to injure England, but, on the other hand, required English support. All this was changed by the occupation of Egypt. Here England required a support on the Continent against the indignation of France and the jealousy of Russia. This could only be found in Germany, and therefore a close approximation between the two countries was natural. Bismarck let it be known that England would find no support, but rather opposition, if she, on her side, attempted, as she so easily could have done, to impede German colonial enterprise.

In his colonial policy Bismarck refused to take the initiative; he refused, also, to undertake the direct responsibility for the government of their new possessions. He imitated the older English plan, and left the government in the hands of private companies, who received a charter of incorporation; he avowedly was imitating the East India Company and the Hudson's Bay Company. The responsibilities of the German Government were limited to a protection of the companies against the attack or interference by any other Power, and a general control over their actions. In this way it was possible to avoid calling on the Reichstag for any large sum, or undertaking the responsibility of an extensive colonial establishment, for which at the time they had neither men nor experience. Another reason against the direct annexation of foreign countries lay in the Constitution of the Empire; it would have been easier to annex fresh land to Prussia; this could have been done by the authority of the King; there was, however, no provision by which the Bundesrath could undertake this responsibility, and it probably could not be done even with the assent of the Reichstag unless some change were made in the Constitution. It was, however, essential that the new acquisitions should be German and not Prussian.

All these changes were not introduced without much opposition; the Progressives especially distinguished themselves by their prolonged refusal to assent even to the subsidies for German lines of steamers. In the Parliament of 1884 they were enabled often to throw out the Government proposals. It was at this time that the conflict between Bismarck and Richter reached its height. He complained, and justly complained, that the policy of the Progressives was then, as always, negative. It is indeed strange to notice how we find reproduced in Germany that same feeling which a few years before had in England nearly led to the loss of the colonies and the destruction of the Empire.

It is too soon even now to consider fully the result of this new policy; the introduction of Protection has indeed, if we are to judge by appearances, brought about a great increase in the prosperity of the country; whether the scheme for old-age pensions will appease the discontent of the working man seems very doubtful. One thing, however, we must notice: the influence of the new policy is far greater than the immediate results of the actual laws passed. It has taught the Germans to look to the Government not only as a means of protecting them against the attacks of other States, but to see in it a thoughtful, and I think we may say kindly, guardian of their interests. They know that every attempt of each individual to gain wealth or power for his country will be supported and protected by the Government; they know that there is constant watchfulness as to the dangers to life and health which arise from the conditions of modern civilisation. In these laws, in fact, Bismarck, who deeply offended and irretrievably alienated the survivors of his own generation, won over and secured for himself and also for the Government the complete loyalty of the rising generation. It might be supposed that this powerful action on the part of the State would interfere with private enterprise; the result shews that this is not the case. A watchful and provident Government really acts as an incentive to each individual. Let us also recognise that Bismarck was acting exactly as in the old days every English Government acted, when the foreign policy was dictated by the interests of British trade and the home policy aimed at preserving, protecting, and assisting the different classes in the community.

Bismarck has often been called a reactionary, and yet we find that by the social legislation he was the first statesman deliberately to apply himself to the problem which had been created by the alteration in the structure of society. Even if the solutions which he proposed do not prove in every case to have been the best, he undoubtedly foresaw what would be the chief occupation for the statesmen of the future. In these reforms he had, however, little help from the Reichstag; the Liberals were bitterly opposed, the Socialists sceptical and suspicious, the Catholics cool and unstable allies; during these years the chronic quarrel between himself and Parliament broke out with renewed vigour. How bitterly did he deplore party spirit, the bane of German life, which seemed each year to gain ground!

"It has," he said, "transferred itself to our modern public life and the Parliaments; the Governments, indeed, stand together, but in the German Reichstag I do not find that guardian of liberty for which I had hoped. Party spirit has overrun us. This it is which I accuse before God and history, if the great work of our people achieved between 1866 and 1870 fall into decay, and in this House we destroy by the pen what has been created by the sword."

In future years it will perhaps be regarded as one of his chief claims that he refused to become a party leader. He saved Germany from a serious danger to which almost every other country in Europe which has attempted to adopt English institutions has fallen a victim—the sacrifice of national welfare to the integrity and power of a Parliamentary fraction. His desire was a strong and determined Government, zealously working for the benefit of all classes, quick to see and foresee present and future evil; he regarded not the personal wishes of individuals, but looked only in each matter he undertook to its effect on the nation as a whole. "I will accept help," he said, "wherever I may get it. I care not to what party any man belongs. I have no intention of following a party policy; I used to do so when I was a young and angry member of a party, but it is impossible for a Prussian or German Minister." Though the Constitution had been granted, he did not wish to surrender the oldest and best traditions of the Prussian Monarchy; and even if the power of the King and Emperor was limited and checked by two Parliaments it was still his duty, standing above all parties, to watch over the country as a hundred years before his ancestors had done.

FRIEDRICHSRUHE.

FROM A PHOTOGRAPH BY STRUMPER & CO., HAMBURG.

Bismarck often complained of the conduct of the Reichstag. There were in it two parties, the Socialists and the Centre, closely organised, admirably disciplined, obedient to leaders who were in opposition by principle; they looked on the Parliamentary campaign as a struggle for power, and they maintained the struggle with a persistency and success which had not been surpassed by any Parliamentary Opposition in any other country. Apart from them the attitude of all the parties was normally that of moderate criticism directed to the matter of the Government proposals. There were, of course, often angry scenes; Bismarck himself did not spare his enemies, but we find no events which shew violence beyond what is, if not legitimate, at least inevitable in all Parliamentary assemblies. The main objects of the Government were always attained; the military Budgets were always passed, though once not until after a dissolution. In the contest with the Clerical party and the Socialists the Government had the full support of a large majority. Even in the hostile Reichstag of 1884, in which the Socialists, Clericals, and Progressives together commanded a majority, a series of important laws were passed. Once, indeed, the majority in opposition to the Government went beyond the limits of reason and honour when they refused a vote of £1000 for an additional director in the Foreign Office. It was the expression of a jealousy which had no justification in facts; at the time the German Foreign Office was the best managed department in Europe; the labour imposed on the secretaries was excessive, and the nation could not help contrasting this vote with the fact that shortly before a large number of the members had voted that payments should be made to themselves. The nation could not help asking whether it would not gain more benefit from another £1000 a year expended on the Foreign Office than from £50,000 a year for payment of members. Even this unfortunate action was remedied a few months later, when the vote was passed in the same Parliament by a majority of twenty.

Notwithstanding all their internal differences and the extreme party spirit which often prevailed, the Reichstag always shewed determination in defending its own privileges. More than once Bismarck attacked them in the most tender points. At one time it was on the privileges of members and their freedom from arrest; both during the struggle with the Clericals and with the Socialists the claim was made to arrest members during the session for political utterances. When Berlin was subject to a state of siege, the President of the Police claimed the right of expelling from the capital obnoxious Socialist members. On these occasions the Government found itself confronted by the unanimous opposition of the whole House. In 1884, Bismarck proposed that the meetings of the Reichstag should be biennial and the Budget voted for two years; the proposal was supported on the reasonable grounds that thereby inconvenience and press of work would be averted, which arose from the meeting of the Prussian and German Parliaments every winter. Few votes, however, could be obtained for a suggestion which seemed to cut away the most important privileges of Parliament.

Another of the great causes of friction between Bismarck and the Parliament arose from the question as to freedom of debate. Both before 1866, and since that year, he made several attempts to introduce laws that members should be to some extent held responsible, and under certain circumstances be brought before a court of law, in consequence of what they had said from their places in Parliament. This was represented as an interference with freedom of speech, and was bitterly resented. Bismarck, however, always professed, and I think truly, that he did not wish to control the members in their opposition to the Government, but to place some check on their personal attacks on individuals. A letter to one of his colleagues, written in 1883, is interesting:

"I have," he says, "long learned the difficulties which educated people, who have been well brought up, have to overcome in order to meet the coarseness of our Parliamentary Klopfechter [pugilists] with the necessary amount of indifference, and to refuse them in one's own consciousness the undeserved honour of moral equality. The repeated and bitter struggles in which you have had to fight alone will have strengthened you in your feeling of contempt for opponents who are neither honourable enough nor deserve sufficient respect to be able to injure you."

There was indeed a serious evil arising from the want of the feeling of responsibility in a Parliamentary assembly which had no great and honourable traditions. He attempted to meet it by strengthening the authority of the House over its own members; the Chairman did not possess any power of punishing breaches of decorum. Bismarck often contrasted this with the very great powers over their own members possessed by the British Houses of Parliament. He drew attention to the procedure by which, for instance, Mr. Plimsoll could be compelled to apologise for hasty words spoken in a moment of passion. It is strange that neither the Prussian nor the German Parliament consented to adopt rules which are really the necessary complement for the privileges of Parliament.

The Germans were much disappointed by the constant quarrels and disputes which were so frequent in public life; they had hoped that with the unity of their country a new period would begin; they found that, as before, the management of public affairs was disfigured by constant personal enmities and the struggle of parties. We must not, however, look on this as a bad sign; it is rather more profitable to observe that the new institutions were not affected or weakened by this friction. It was a good sign for the future that the new State held together as firmly as any old-established monarchy, and that the most important questions of policy could be discussed and decided without even raising any point which might be a danger to the permanence of the Empire.

Bismarck himself did much to put his relations with the Parliament on a new and better footing. Acting according to his general principle, he felt that the first thing to be done was to induce mutual confidence by unrestrained personal intercourse. The fact that he himself was not a member of the Parliament deprived him of those opportunities which an English Minister enjoys. He therefore instituted, in 1868, a Parliamentary reception. During the session, generally one day each week, his house was opened to all members of the House. The invitations were largely accepted, especially by the members of the National Liberal and Conservative parties. Those who were opponents on principle, the Centre, the Progressives, and the Socialists, generally stayed away. These receptions became the most marked feature in the political life of the capital, and they enabled many members to come under the personal charm of the Chancellor. What an event was it in the life of the young and unknown Deputy from some obscure provincial town, when he found himself sitting, perhaps, at the same table as the Chancellor, drinking the beer which Bismarck had brought into honour at Berlin, and for which his house was celebrated, and listening while, with complete freedom from all arrogance or pomposity, his host talked as only he could!

The weakest side of his administration lay in the readiness with which he had recourse to the criminal law to defend himself against political adversaries. He was, indeed, constantly subjected to attacks in the Press, which were often unjust and sometimes unmeasured, but no man who takes part in public life is exempt from calumny. He was himself never slow to attack his opponents, both personally in the Parliament, and still more by the hired writers of the Press. None the less, to defend himself from attacks, he too often brought his opponents into the police court, and Bismarckbeleidigung became a common offence. Even the editor of Kladderadatsch was once imprisoned. He must be held personally responsible, for no action could be instituted without his own signature to the charge. We see the same want of generosity in the use which he made of attempts, or reputed attempts, at assassination. In 1875, while he was at Kissingen, a young man shot at him; he stated that he had been led to do so owing to the attacks made on the Chancellor by the Catholic party. No attempt, however, was made to prove that he had any accomplices; it was not even suggested that he was carrying out the wishes of the party. It was one of those cases which will always occur in political struggles, when a young and inexperienced man will be excited by political speeches to actions which no one would foresee, and which would not be the natural result of the words to which he had listened. Nevertheless, Bismarck was not ashamed publicly in the Reichstag to taunt his opponents with the action, and to declare that whether they would or not their party was Kuhlmann's party; "he clings to your coat-tails," he said. A similar event had happened a few years before, when a young man had been arrested on the charge that he intended to assassinate the Chancellor. No evidence in support of the charge was forthcoming, but the excuse was taken by the police for searching the house of one of the Catholic leaders with whom the accused had lived. No incriminating documents of any kind were found, but among the private papers was the correspondence between the leaders in the party of the Centre dealing with questions of party organisation and political tactics. The Government used these private papers for political purposes, and published one of them. The constant use of the police in political warfare belonged, of course, to the system he had inherited, but none the less it was to have been hoped that he would have been strong enough to put it aside. The Government was now firmly established; it could afford to be generous. Had he definitely cut himself off from these bad traditions he would have conferred on his country a blessing scarcely less than all the others.

The opposition of the parties in the Reichstag to his policy and person did not represent the feelings of the country. As the years passed by and the new generation grew up, the admiration for his past achievements and for his character only increased. His seventieth birthday, which he celebrated in 1885, was made the occasion for a great demonstration of regard, in which the whole nation joined. A national subscription was opened and a present of two million marks was made to him. More than half of this was devoted to repurchasing that part of the estate at Schœnhausen which had been sold when he was a young man. The rest he devoted to forming an institution for the help of teachers in higher schools. A few years before, the Emperor had presented to him the Sachsen Wald, a large portion of the royal domains in the Duchy of Lauenburg. He now purchased the neighbouring estate of Friedrichsruh, so that he had a third country residence to which he could retire. It had a double advantage: its proximity to the great forest in which he loved to wander, and also to a railway, making it little more than an hour distant from Berlin. He was able, therefore, at Friedrichsruh, to continue his management of affairs more easily than he could at Varzin.