Canadian Alpine Journal/Volume 1/Number 2/Expedition to Lake O'Hara

To a nature-lover, the invitation of the Alpine Club of Canada to the Mazamas to send a representative to the Annual Meet in the summer of 1907 was very alluring with its brief hints of the scenery one might expect in and around Paradise Valley. And especially attractive was its suggestion of a two-days' expedition among glaciers and over passes in the vicinity.

I had years before looked with longing eyes from the train as we caught fleeting glimpses of distant snow-peaks and deep glacier-cut valleys, and when the call came to me in Oregon to penetrate the mysteries of the Rockies I eagerly accepted.

Oregon and Washington have attractive snow scenery, but it is largely centred about individual volcanic peaks rising like sentinels above the densely wooded region around them. I had made the ascent of our more prominent peaks, and was anxious to make comparisons. Entering Paradise Valley a stranger, I left it with so many pleasant memories that, as I now mentally retrace my steps and glance again at the photographs before me, as I have so many times, I experience a keen pleasure that only Alpine enthusiasts can possibly appreciate.

Paradise Valley is well named, for it lies in the center of a wonderful scenic region and makes an ideal place for a club camp. From the summit of Mount Temple above the valley, I gazed over a bewildering sea of snow peaks and looked with envious eyes in the direction of Lake O'Hara, eager to make the circuit of the lakes. That evening I entered my name for the O'Hara Expedition, and the following morning, rising with the sun or shortly thereafter, made one of a small group around the fire, for the early air was sharp and biting.

Breakfast over, seven responded to the roll-call and the click of the alpenstock announced our departure from camp. We trailed along up the timbered valley on the left bank of the stream rushing madly down from Horseshoe Glacier. Crossing the stream about a mile from camp, just above the Giant's Stairway, over which the water glides in liquid sheets, we came close to the Mitre, a prominent peak overhanging the valley, and so named from its resemblance to a bishop's mitre. Here we commenced our ascent towards the pass between the Mitre and Mt. Aberdeen, working up a rocky slide, of which the lower portion was covered with small brush. We were soon taking a breather on the first bench above, where the snow began. As a matter of practice and precaution the rope was uncoiled, and, while our leader was making the necessary loops, we turned and absorbed the view. Paradise Valley lay before us, a carpet of green, walled in by snow peaks reaching from the glacial amphitheatre at its head down its entire length. Mount Temple raised its snowy dome across the way, with Pinnacle, Eiffel and the other peaks forming a massive semi-circle curving towards where we stood.

The loops adjusted, we started the climb over the snow, and after a rather strenuous pull made the pass and looked down the other slope, which led to Lefroy Glacier and proved much steeper than the route up. Some difficulty had been experienced here on the previous expedition, as the snow then had a hard crust, necessitating a tedious process of step-cutting. We were fortunate, however, as we found the snow in good condition, and, going cautiously at the start, we soon broke rank and slid—first one ahead and then another—until what appeared like a forbidding descent was soon over and we were out on the glacier.

Where Lefroy and Victoria Glaciers meet we found the surface badly broken, necessitating rather cautious movement and obliging us in places to jump over partially concealed crevasses. Here we paused to take in the view. We were at the head of another valley, wilder and more interesting than Paradise. The Mitre and Lefroy looked down on us, as their other sides did on Paradise Valley. Victoria formed the centre of the circle, its huge mass of snow and ice overhanging high rocky walls suggesting something familiar. Turning, the eye swept down the valley of ice and there below us, a pure gem in a perfect setting, appeared a small lake of liquid blue. "Lake Louise!" someone exclaimed; and, like a flash, I then recalled gazing through powerful binoculars towards Lefroy and Victoria from the Chalet by the lake, wondering at the time if I would have the good fortune to stand where we now stood. The Chalet was plainly visible, and beyond we could see Laggan, the railroad and other signs of prosaic existence.

Awakened from a reverie by the warning that we must make Abbot Pass before the sun should loosen the dangerous snow masses by its piercing rays, we reluctantly turned, and taking our way around the bulwark of Lefroy, looked up the Victoria Glacier to Abbot Pass. The precipitious walls of Lefroy and Victoria on either side force snow into this narrow gap.

A clear blue canopy of sky brought out the vivid whiteness of the pass, and the incline of the vision following the upward slope belittled the intervening distance and made the pass seem almost insignificant. Why was it called the "Death Trap"? Why was it dangerous? Why the warning to take a long breath and no halt? The answers came as we pushed upward, the pass apparently receding as we advanced and yet near enough to lure us on. As we zigzagged up, huge masses of snow lay in loosely piled heaps, rising high above us, almost forbidding a whisper lest it start an avalanche; and the sun, MITRE PASS AND LEFROY GLACIER DEATH-TRAP AND ABBOT PASS

Copyright, 1902, by Detroit Photographic Company

MOUNT LEFROY AND VICTORIA GLACIER

It seems a misnomer to call the gap between Lefroy and Victoria a pass. Higher than the average snow peak, a precipitious slope on either side, we stood on the knife-edge of the pass, caught our breath and lost it again as we gazed down the other slope. We looked into chaotic grandeur, snow and rock everywhere in an endless uplift. Reluctantly we commenced the descent, fortune again favoring us as the slope in places permitted cautious sliding, and before we realized it we were down the narrow funnel and on the ridge that jutted out from the main wall. Here someone suggested lunch, and the suggestion meeting with favor, we selected a place where we could take in the view and enjoy a sun-bath as well. The rocks, though a rather hard resting place, were a welcome relief from the snow, lack of water being the only drawback. Above us towered Lefroy, further to the left rose Mt. Yukness, and below, at the base of glaciers and snow-fields, we could see Lake Oeesa,[1] its ice-covered surface making the water seem black by contrast. The lake is seldom free from ice on account of its elevation.

After a brief rest and the inner man appeased, we made our way down the ledges and then down a talus or rock-slide above Oeesa. Here we caught a glimpse of Lake O'Hara in the valley below. Following down the bed of the valley for several miles, we suddenly came out on the rim of a rock-wall and below us saw the lake, its mirror-like surface reflecting the snow peaks surrounding it.

The lake is about a mile long, of irregular shape, in places half a mile wide, the further shore broken in a series of inviting coves covered with evergreen trees reaching to the water's edge. To our right Wiwaxy Peaks, a huge buttress of oddly-shaped rock pinnacles, rose abruptly from the water, cutting off the further end from view, while across rose Mount Schaffer. It was then about three o'clock, and the afternoon light brought out the vivid blue of the water. Not a trace of human presence, not a trace of any disturbing element, the whole scene was the personification of majestic peace.

The Alpine Club had established a temporary camp on the shore of the lake to take care of parties making the circuit from the main camp, the tents and supplies being packed in over a trail from Hector. We looked for the camp but failed to locate it, as it was hidden in one of the distant coves. Hesitating to break the stillness, we finally hallooed, the call echoing and re-echoing from shore to shore, but no one answered. We were puzzled at first how to reach the lake as the descent was almost a sheer drop of several hundred feet, but after careful experimenting, a route was selected requiring caution, and we were soon at the water's edge.

Satisfying our thirst from a small torrent of pure water, we followed the left shore over a mossy bank, through a natural park, and came in sight of the camp about three-quarters of the way down the lake, a most welcome sight. A refreshing plunge in the water gave additional zest to our appetite for the evening meal, which soon followed. The air was cool enough to make the fire welcome, and the hard tramp, bath and supper had put us in a condition of blissful laziness. Lounging there we could see the evening glow and the deepening shadows on the lake, and on the mountains and glaciers beyond. Going up to a meadow about a mile distant, we secured the full effect of the afterglow on the snow peaks back of the camp. The twilight was gracious in its length,

THE EAGLE'S EYRIE

PROSPECTOR'S VALLEY

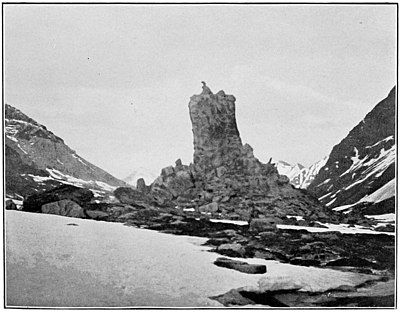

After a restful sleep, which you often fail to get in city turmoil, we arose as Aurora, rosy-fingered dawn, was tinting the rocks and glaciers in soft morning light. Breakfast over, we continued our circuit. Above the timber-line we stopped at Crystal Cave to secure specimens and a farewell view of the lake. Like Lot's wife, we could not resist glancing back for just one more view to salt down in our memory. Opabin Pass was the first goal, and on our way up, on the benches above, we passed two small lakes covered with floating ice. In skirting them we sank repeatedly in the loose snow, making slow progress. From above the lakes, looking westward, a panorama of mountain scenery was presented, broader and more extensive than we had enjoyed at Lake O'Hara. In the distance we could see Mount Odaray prominent among many other peaks. Light clouds in the clear blue sky heightened the effect. Opabin Pass lacked the elements of danger and the strenuousness of Abbot Pass. A good long pull over the pass and a slide and coast on the other side brought us down the slope below the snow-field; and on a rocky, heather-covered knob, where we could shake the snow from our feet, and bask in the sunshine, we ate lunch, with plenty of sparkling water and a glorious view to feast on. Just below us stood the Rock Tower, a curious monolith rising above the bed of the valley. Keeping to the left, we worked along the side of the valley a short distance until we reached the rock-slide below Wenkchemna Pass. Struggling up over small loose rock and then stepping on larger boulders, we reached snow-line, the sun a blaze of glory at our backs, reflecting the heat from snow and rock into our faces. A gentle breeze on the summit of the pass proved very welcome. We were now looking down the Valley of the Ten Peaks, ten snow peaks forming the right side of the valley.

From the lofty mountains of Oregon and Washington, the view lies all below, no rival near. From these different passes peaks lifting everywhere fairly bewilder one; and it makes it all the more impressive to realize that you are not far from the Great Divide, the source or fountainhead from which streams branch out to flow eventually into three different oceans. The descent into the valley would have been easy had the snow been firmer . We broke through repeatedly, sometimes waist deep. Three of our party soon left us to keep on down to Moraine Lake, a few miles away, where another side camp had been established. We ascended the left slope of the valley, and after a rather steep rock climb reached snow again and quickly made Wastash Pass, just west of Eiffel Peak, and looked into Paradise Valley.

We were now opposite the Mitre Pass, the first pass of the preceding day's tramp. We hurried down, enjoying several steep slides in the snow, and were soon retracing our way down the valley, making the main camp in time for supper; having seen more in two days than could be seen elsewhere in months, an expedition never to be forgotten.

OPABIN PASS—LOOKING SOUTH-EAST

PASS NO. 3 OF TWO-DAY EXPEDITION

WENKCHEMNA PASS—LOOKING EAST

PASS NO. 4 OF TWO-DAY EXPEDITION

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1929.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1927, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 96 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

![]()

This work is in the public domain in Canada because it originates from Canada and one of the following statements is true:

- The author died over 70 years ago (before 1954) and the work was published more than 50 years ago (before 1974).

- The author died before 1972, meaning that copyright on that author's works expired before the Canadian copyright term was extended non-retroactively from 50 to 70 years on 30 December 2022.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1927, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 96 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

- ↑ Indian word meaning "Ice."