Canadian Alpine Journal/Volume 1/Number 2/Three Attempts on Pinnacle

CANADIAN ALPINE JOURNAL

PUBLISHED BY

MOUNTAINEERING SECTION.

THREE ATTEMPTS ON PINNACLE.

By P. D. McTavish.

Pinnacle Mountain is bold and precipitous with somewhat of a castellated appearance. It is situated between Paradise Valley and the Valley of the Ten Peaks and behind or southwest of Mt. Temple, which overshadows it by upwards of 1,500 feet. Its altitude is only 10,062 ft., but the steepness of its walls on all sides, and the rottenness of its rock combine to make it extremely difficult of ascent. In fact it has so far defied the efforts of all who have attempted to reach its summit.

During the summer of 1907, the year in which the Alpine Club of Canada met in Paradise Valley, three attempts were made to conquer it. On June 24 Mr. Forde of Revelstoke with Guide Peter Kaufmann made the first attempt, the Alpine Club sent a party composed of the Reverends J. C. Herdman, J. R. Robertson and Geo. B. Kinney and P. D. McTavish in charge of the guide Edouard Feuz Jr. on July 9; and on August 22 Dr. Hickson of Montreal with both Peter and Edouard made the third unsuccessful attempt.

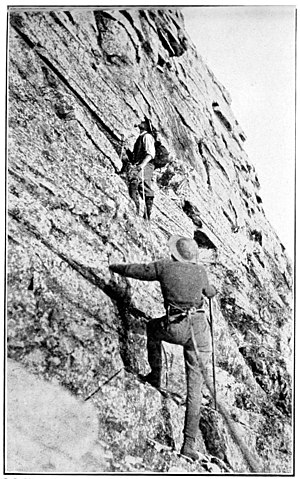

The Alpine Club's party left camp at six o'clock, and, after the usual tramp through the woods and over the 2,500 feet of loose rock and snow forming the mountain's lower slopes, we encountered the first real work. This consisted in the ascent of a long, steep couloir filled with much loose rock on which rested, most insecurely, from six to twelve inches of snow and ice. In spite of the greatest precaution we dislodged some boulders and a considerable amount of finer debris, snow and ice. As we approached the top of the chimney the snow increased in quantity and steepness, becoming almost perpendicular, so our ice-axes were called into use.

Regarding this particular part of the mountain Mr. Forde writes in his account of the climb: "About seven o'clock the first work began at an elevation of about 9,000 feet, up a small couloir, and, as the rocks were icy and covered with from six to twelve inches of snow, the rope was brought into use. Here one of the pleasures so often experienced by mountain climbers fell to the lot of the writer, that of hanging on to the face of the rock wall while the man above sent a steady stream of snow and lumps of ice on the top of his head and down his neck, while his fingers were getting numb and stiff and he was beginning to doubt the existence of such things as toes. Surely one is justified in asking at such times the question: Is life worth living? After about two hours of this work, during which the two climbers 'spelled' each other in cutting steps and finger-holds, about 125 feet had been gained, and they reached a small shoulder of the mountain, projecting into the Wastash Pass. Up this shoulder the travelling was comparatively good for 200 feet more, and then they were brought to a stop

Having finally reached the top of the couloir we found ourselves on a narrow ridge which connected a gendarme to the body of the mountain. This ridge was so narrow that there was barely room for our party to sit down, while the rock was so disintegrated that we wondered why col and gendarme did not go crashing to the depths below We had been climbing five hours, and now halted for a breathing spell and a sandwich. Resuming the climb, we found ourselves confronted by a perpendicular wall several hundred feet in height, therefore turned south towards Eiffel Peak. Our first work was a very difficult descent of about fifty feet which landed us in a sort of funnel-shaped amphitheatre. Its walls were very steep and its outlet led to a perpendicular drop of 500 feet. We crossed safely by a narrow ledge and soon found ourselves on the col joining Pinnacle Mountain and Eiffel Tower.

Looking upwards (northerly) Pinnacle Mountain presented the appearance of a succession of cascades of honeycombed rock which seemed ready to crumble were any extra weight put upon them or the rain to saturate them. For an hour we scaled this succession of perpendicular faces and had little trouble except that the rottenness of the rock made more or less hazardous our every movement.

Finally about one o'clock we reached the base of the precipice-walled crown which surmounted the rest of the mountain, the "keep" as it were of the fortress. Its walls rose in a perpendicular face and seemed to defy us. We went to right and to left only to find that the same perpendicular face extended comlpetely around the mountain, guarding jealously its summit. There seemed but one chance: A huge crack cleft the face of the crown, reaching apparently to the summit, and it looked as though we might be able to work our way up. For about forty or fifty feet we had little difficulty, but beyond that the way was absolutely blocked by the steepness of the rock and its utter lack of hand-holds and foot-holds. For fully an hour the guide struggled at this point. Finally one of the party braced himself and allowed Edouard to climb upon his shoulders in the hope that the advantage thus gained would reveal new possibilities. But the effort was useless and we were reluctantly forced to retreat.

It was now suggested that we try to work our way up the walls of the huge crack at a point farther in where it was not as wide, but upon examination we found these walls covered with ice and the hope of getting up here was quickly dispelled. Then began a more careful examination; but, after reconnoitering to right and left we found no place where there was the slightest possibility of ascending, so returned to the fissure once more. For upwards of an hour we redoubled our efforts at this point, but all to no effect, and finally decided unanimously that we were defeated. Mr. Forde's experience at this point follows: "The foot of the wall was traversed on a small ledge for several hundred feet easterly, along the side of the mountain, above the Valley of the Ten Peaks, but further progress was barred by the ledge ending suddenly. As no place was found at which it was possible to attempt to get higher, the climbers retraced their steps to the shoulder mentioned before and continued around the face of the wall towards Paradise Valley. Here again no practicable route to the top was found, the only place that seemed at all likely to be feasible being a narrow crevice in the face of the wall. This crevice looked anything but promising, but as it was the only chance left, it was attempted and some progress made by pressing the elbows and knees against the sides and working up a few inches at a move. About fifty feet from the bottom of the crevice it widened out to six or eight feet. As the walls were smooth and perpendicular, and the

It was now four o'clock. If loose and rotten rock was dangerous on the ascent, it would be doubly so descending, and it was imperative to commence the descent. With the chagrin of defeat in our minds, we did not particularly relish the anticipation of descending faces of weathered and disintegrating rock, skirting fearsome ledges with foot-holds of questionable security and yawning depths below and, worst of all, lowering ourselves down couloirs treacherous with snow, ice and debris.

Proceeding carefully we reached the top of the last and longest couloir about seven o'clock. To its base the depth was fully 200 feet, and we dreaded this more than any part of the whole descent. The sun was approaching the mountain peaks to the west, the air had become noticeably cool, speed was necessary. Eight hundred feet below was the snow-field; unless we reached it before dark we might have the uncomfortable experience of spending a night above snow-line, an experience which none of us desired. Just as we had nicely entered the chimney the guide, Edouard, called a halt until he should examine another route apparently more feasible. It was; but the first thirty or forty feet seemed quite hazardous, so one member of the party was lowered by a rope to examine the rock carefully. It seemed better than the couloir and soon all had descended and we were approaching the snow-field, which we eventually reached about eight o'clock, feeling much relieved that the dangers were over before darkness set in. We arrived at the camp about nine o'clock, just as the evening shadows were creeping over Paradise Valley, and the warm glow and pleasant crackle of the camp fire were making many merry hearts merrier.

The third attempt of Pinnacle Mountain was made on the 22nd of August last by Dr. J. W. A. Hickson, of McGill College, Montreal. The account of it is given in his own words:

"I started in the afternoon of August 21st from Lake Louise with Peter Kaufman and Edouard Feuz, Jr., and camped one night on the site of the Canadian Alpine Club camp in 1907. We had camped here a week before, but had been driven back from our proposed attempt on Pinnacle by heavy rain and snow. When we were taking supper, in full view of the mountain, it seemed to me that the guides were by no means so hopeful of attaining the summit as they had been previously. Feuz even remarked in no genuinely joking tone: 'Perhaps we won't get to the top.' Needle-like in appearance, its summit covered with fresh snow looked cold and forbidding, and very diminutive alongside of the massive Temple.

"We set out next morning about 5 o'clock, in fine weather. After following the stream which flowed past the camp, we ascended a grassy slope and over some boulders along the left shoulder of the mountain. In about three hours we reached the snow, which was fresh and powdery, and the rope was brought into requisition. Proceeding carefully up the snow-slope, we crossed to the right and following the ridge, which one of the guides had traversed some weeks before, had some good rock climbing. In some place the foot-holds were rendered easier by the hard snow, particularly on a narrow ledge skirting the right shoulder of the mountain near the top; but elsewhere the rocks were unpleasantly slippery through melting snow. We had reached a ledge within what seemed to be about 300 feet below the summit, when further advance was stopped by a precipitous wall

"It was now about 10.15 o'clock. The weather though fairly clear, had turned unpleasantly cold, and there were heavy clouds moving from the west with a high wind. After taking some refreshment the guides suggested that they should first try the chimney, in regard to the feasibility of which I was not at all hopeful. As the result of half an hour's work Feuz managed to ascend some 15 or 20 feet, but there was no prospect of getting further in this direction. We then explored both sides of the ledge to discover whether there was any way of working round the wall of rock and ascending to the summit from another side. We came to the conclusion, however, that what seemed to offer a possible means of circumvention was, on account of the fresh snow on the loose rocks, too dangerous to be worth the risk. The guides were strongly opposed to undertaking it. So we left the ridge very reluctantly about 12.30 o'clock with the intention of seeing something more of the mountain by descending on the opposite side to that along which we had come up. But, after getting down about a thousand feet, we were obliged, again owing to the condition of the snow, to ascend in order to resume our previous path. We reached camp at 4.40 p.m. It seems to me that it would be worth while trying this peak again only when it is completely dry, i.e., free of snow for 1,000 feet below the summit. Last summer was notoriously unfavorable for mountaineering, as fresh snow fell almost continuously after the beginning of August on all peaks over 8000 feet."

Defeat does not always mean lack of pleasure, for in mountain climbing (as in most other things) the very striving itself is enjoyable. "Strive, nor hold cheap the strain." When a party of mountaineers, protected from danger by a careful guide, spend a day on a mountain that tries all their skill and constantly taxes their ingenuity, every moment is replete with pleasure. So our fifteen hours spent on Pinnacle Mountain was a decided success even though we failed to reach the summit. All honor to the man who finally performs the feat.

![]()

This work is in the public domain in the United States because it was published before January 1, 1930.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1927, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 97 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse

![]()

This work is in the public domain in Canada because it originates from Canada and one of the following statements is true:

- The author died over 70 years ago (before 1955) and the work was published more than 50 years ago (before 1975).

- The author died before 1972, meaning that copyright on that author's works expired before the Canadian copyright term was extended non-retroactively from 50 to 70 years on 30 December 2022.

The longest-living author of this work died in 1927, so this work is in the public domain in countries and areas where the copyright term is the author's life plus 97 years or less. This work may be in the public domain in countries and areas with longer native copyright terms that apply the rule of the shorter term to foreign works.

![]()

Public domainPublic domainfalsefalse