Cassell's Illustrated History of England/Volume 1/Chapter 68

CHAPTER LXVIII.

THE PROGRESS OF THE NATION.

FORMATION OF THE ENGLISH PEOPLE.

We have already stated our views of the true nature of human history. We do not believe it to consist merely or chiefly in the records of the wars and butcheries which have disgraced the earth. Those may have built up some nations and pulled down others, but, in the aggregate, they have retarded the progress of the race, they have distorted the intellectual vision of mankind, lowered and vitiated the standard of morals, and, by engrossing the energies of the ablest men in the pursuit of mutual destruction, have necessarily diverted them from the pursuit of all those arts which grace and that knowledge which elevates society. We believe that historians, by devoting nearly all their faculties, their passions, and their lives, their eloquence, their learning, and their logic, to the martial rather than the social history of their respective countries, have done more than all other men put together to perpetuate the false taste for sanguinary fame, and, consequently, to curse their fellow-men with a growth of warriors rather than of the true heroes of our race—those who combat errors, and who establish in our midst the triumphs of mind. Had historians placed these in the foremost ranks, and spoken of the mere physical warriors in more moderate and just terms, the world would have presented to-day a very different aspect; and, instead of Europe armed to the teeth, not so much to defend as to offend the respective peoples, and with its myriads groaning under a leaden despotism which is oppressing not only its limbs but its brain, we should have already advanced far beyond the railway and the electric telegraph, into the regions of beneficent science, and seen nations exchanging all the blessings of mutual discoveries and mutual good-will, instead of the deadly point of the bayonet and the muzzle of the gun. We now, therefore, pause in the narrative of that heritage of national contentions which our predecessors have left us, to glean up as we may a few traces of the real history of England; that is, of its religious, moral, and artistic progress during the interval between the Norman period and the present. And, first, let us say a word of the nation whose history we are tracing, as it may help the imagination of the reader to comprehend the greatness of the subject. We may suspect, when we ourselves pronounce our own people the first and foremost in the world, that national vanity may influence the judgment.

A Scandinavian God.

But we will quote the opinion of a distinguished writer of our rival, France, recently given, who cannot be supposed guilty of such bias. M. Gouraud, in his "Histoire des Causes de la Grandeur de l'Angleterre," says:—

"What a nation! Foremost in intelligence, and in the application of the useful arts, she disputes the palm in other regions of activity, and carries it in some. Is this all? No. Add that this great people is free! Free! when the rest of mankind, while pretending to rival them, can only move with anarchy, or rest in servitude. Free! that is, equally capable of discussing and respecting their laws. Free! that is, wise enough to govern themselves for the direction of their own affairs. Other mercantile nations before England have been, or believed themselves to be free. But what was the liberty of Carthage, of Venice, or even Amsterdam, beside that of London? A word beside a reality. And then England, to the imposing material and intellectual spectacle which she offers to the world, may add a third still more striking, and undoubtedly the fairest that can be seen under the heavens—namely, the moral spectacle of a nation that depends upon herself alone. To have a complete idea, however, of the unprecedented grandeur of this nation, we must also take into consideration that, unlike her predecessors in commerce, who never hold more than the most limited moral influence over the nations with which they came in contact, she acts more than any other on the destinies, the mind, and the manners of the rest of the world. Already she is the model school for the agriculturists, the manufacturers, the navigators, and the merchants of the universe.

"Then, inasmuch as by reason of her immense territorial possessions, there is no language so widely spread as hers, she exercises an incalculable influence over the human mind. There are only a few cultivated spirits who, beyond the frontiers of their respective countries, read Dante or Molière, while Shakespeare has readers in every latitude of the globe. And then, too, when the free press or the free tribune of London expresses a sentiment, an idea, or a vow, this sentiment, this vow, this idea, makes the tour of the world. When Junius writes, or Pitt speaks, the universe reads and listens. Thanks, in short, may be given to the justice of Providence, that the people to whom this immense and redoubtable empire has been accorded, can use it only to elevate human intelligence and human dignity: for their language, even in the greatest excess of passion, is always the manly and vivifying utterance of free men. Such is the fine spectacle which the British empire offers to our generation."

Thus nothing can tend so much to invigorate us as the contemplation of the national history, in which the labours and sufferings of our forefathers to build up this grand palladium of our liberties are recorded.

In reviewing the constitutional progress during the period wa have passed through in the late reigns, we cannot do better than commence with an inquiry into the origin and composition of the English people, which, according to our French neighbour, has grown to such greatness, and to the exercise of so transcendent an influence on human destiny. And here we may again avail ourselves of the striking description of that origin given by the same writer:—

"About a century after the invasion of William, when the violence of the first years after the Conquest had begun to give way before a milder régime, it may be said that the great work of the formation of the English nation was accomplished. It was then that the distinct type of a people appeared, which has never had its like in any age of history, and the powerful originality of which eight centuries have only served to deepen. Then appeared a race of men whose appearance, manners, and mind have remained so marvellously distinct from the rest of the human family, that at the present time an individual of it, met under any latitude, is recognised before he has spoken; in short, then appeared the English people.

"How admirable are the care, the energy, and the perseverance with which Nature works, through centuries, at the formation of the nations which she has destined to civilise certain territories! We have here an example with which it is impossible not to be struck. In the designs of God, in the progress of the human race, it is written that England shall play a great part in the development of Western civilisation. For this purpose a people must be formed—I was going to say, must be wrought—whose powerful constitution shall be capable of fulfilling the great task. What takes place? The tribes who were indigenous to these islands being too feeble for such a destiny, are conquered, driven away, or destroyed. Saxons replace them. These Saxons being found insufficient, in their turn are invaded by the Danes. They fight with each other at first, and then melt into a common race. But even this fusion not giving a perfectly satisfactory result, the Normans arrive, whoso accession realises at last the type of the people so long sought after and expected.

"All this takes up an immense length of time, brings about terrible calamities, and necessitates gigantic efforts; but nothing stops, nothing moves, nothing casts down the indomitable and pitiless energy of Nature's work. She labours in the moral as in the physical world. See, in the depths of the earth, or in the caves of the ocean, how rich substances—gold, the diamond, the pearl—are elaborated! The forces here at work, in analyses, transformations, and experiments, and the time expended, are incalculable. And so in the moral world, when Nature has something rare to produce, she exhibits the like perseverance and insensibility, the like exclusive determination to her end. She acted in this way in the formation of the English nation. She counted neither sacrifices, revolutions, nor centuries; because, in this instance—and succeeding ages were destined to prove it—she was making a diamond."

In this statement the author has made one grand omission—the Roman element. After the British natives—no despicable race, as their resistance to Cæsar demonstrated—there came 500 years of Roman life in England. Thus, the splendid organisation of four great races—the aboriginal, the Roman, the Scandinavian, and the Norman—were combined for the production of the English race; and in that race all the prominent characteristics are blended, and yet distinctly marked. In the native British there prevailed at least bravery and love of freedom; in the Roman, a sublime firmness and fortitude of character, with a large spirit of conquest and of agricultural colonisation. In the Scandinavian—that is, the mixture of Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, and old Saxon; the latter not a German, but a Gothic people, living in the modern Sleswick, and part of the great maritime race which stretches along Europe's western shores from Norway to Belgium—we received a spirit of wonderful hardihood, a spirit of conquest, a spirit of naval adventure and domination, a spirit of settlement in vast and varied countries, and a lofty love of the sublime and wonderful in literature. In the Norman, which was but the Norwegian engrafted on the Celtic blood, we derived a mixture of bravery and polish, and a race of rulers who, spite of all our love of independence, sway us and coerce us to the present hour.

Through all this the Scandinavian—or, to use a more familiar term, the Anglo-Saxon—maintained its predominance. The Norman conquest gave us rulers, but not a people. The Saxon nobles gave way or amalgamated with the Norman blood, but the people were and remained an Anglo-Roman-and-Saxon people. Nothing is a more complete proof of this than the language, which in the days of the most regnant Norman dynasty remained Anglo-Saxon, and remains so still. Archbishop Trench, in his analysis of our modern English, shows that, if we divided it into 100 parts, sixty would be Saxon, thirty Latin, five Greek, and only five a combination of other languages, including Norman-French and French. This view of the question is, again, supported by Sir Henry Ellis's analysis of Domesday Book, which shows that at a time when the whole male population of the kingdom included in the survey was only 283,000, the "mesne tenants," or possessors of land, consisted of only 1,400 tenants in capite, of whom the majority were Normans, while 7,871 lesser proprietors were principally Saxons.

Thus, then, the English nation may be said to be thoroughly amalgamated and completed within a hundred years of the Conquest. The upper classes spoke and read Norman-French, but the people still continued to speak Anglo-Saxon; and, notwithstanding the cruel and temptuous manner in which they wore treated by their Norman lords, they never at any period failed to display the sturdiness of their character. They rose again and again in resistance to the Norman yoke. From the death of the Conqueror to the era of Magna Charta was only 128 years: a plain proof of the rapid growth of the English spirit in the nation.

These facts are of so much importance for the right understanding all that comes after of English history, that we shall save ourselves much trouble by briefly reviewing the realities of the case.

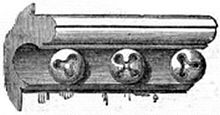

Shipping of the Year 1269.

The charter of John was not the first English charter by any means; and Lingard has very justly observed that, had not John taken arms to get rid of it, we should have heard as little of it as of former ones. Henry I., Stephen, and Henry II. all granted charters, to say nothing of those of Canute and Edward the Confessor; and so far was Magna Charta from extending the liberty secured by those charters, that Lyttleton, the great commentator on our laws, declares the charter of Henry I. was, in some respects, more favourable to liberty than Magna Charta itself. Be that as it may, Magna Charta notoriously originated, not with the barons, but with Stephen Langton, Archbishop of Canterbury. By him it was drawn up in terse and excellent Latin, and bears all the marks, not of the rude composition of feudal barons, but of the great churchman, who at that period was also the great lawyer. Langton was the soul of the whole opposition. He it was who convoked the barons, and read to them the charter of Henry I., and called upon them to compel John to submit to a new one.

The crisis was most auspicious. The people hated John—all men hated him; and the Church had placed him under the ban. The barons had lately joined in the infamous act of making over the country to the Pope, and they were now as ready to join in humbling John.

John, alarmed, humbly besought the Church, as its vassal, to aid him, and the interdict was removed; nay, it was menaced against all who should oppose John. But Langton, spite of the Pope, still pressed on his great object. The barons fought, and were defeated. Their first martial enterprise, the siege of the castle of Northampton, was an utter failure. They saw that without the people they could do nothing. But Bedford and London declared for them, and they were able to bring John to Runnymede. Without other help the barons never could have come there. Church, barons, people-all had combined to bring the tyrant to submission.

Well, the charter was signed, but it was not won. John immediately repudiated it, and the barons rose again in arms to enforce it.

John put down the barons. He raged like a man insane; and we believe that was the secret of his extraordinary and violent character; we believe he was actually insane. He defeated the barons everywhere, except in London, and there the Londoners supported them. But the barons, finding that they could not prevail against John, now perpetrated the most traitorous act which has disgraced the annals of England. They offered the crown of England to the son of Louis, King of France, on condition that he brought over an army to rescue them and their estates from the tyrant who had completely foiled them. Louis came over most gladly, and, had he succeeded, England would have become a dependency of France! But, to the day of John's death,

Prior of Southwick's Chair, 13th Century.—From an Engraving

by the Antiquarian Etching Club.

neither the barons nor the French prince could conquer him. So completely did the barons despair of success, that the Earl of Salisbury, William Marshall, Walter Beaumont, and other barons, abandoned Louis of France and submitted to John; nay, the chroniclers assert that, in his last moments, John received letters from forty of the revolted barons, offering to return to his allegiance, and, of course, to abandon the charter.

So stood affairs at the death of John—he never restored the charter. At this time Louis and the barons not only held London and the south of England, but were powerfully supported in the north by the King of Scotland, and in the west by the prince of the Welsh. The king was but a boy of ten years of age, and, of course, he was made by his guardian, the Earl of Pembroke, to promise charters of anything. A civil war was now become the consequence of the rash act of the barons, and they and their adopted French king stood arrayed against the English king and tho people. Pembroke, whom we believe to have been a good patriot, was disposed to make a truce, and thus to draw tho barons from Louis. But the people cared for neither truce, barons, nor Frenchmen. The sailors, under the brave Hubert de Burgh, the constable of Dover, and the gallant archers of England, under William de Collingham, went hand and heart to work; and so well did they play their part that, in one single year, they had beaten the French and their baronial allies on all hands, and expelled Louis and the Frenchmen from the kingdom. From Collingham's archers Louis himself only escaped by flying on board his ships; and on his return with fresh forces from France, the sailors cut off and captured many of his ships, the bowmen drove the French out of London, and the mariners, under Do Burgh, completed the business by destroying the whole French fleet at the mouth of the Thames with the exception of fifteen vessels.

King Henry III. was firmly set upon the throne, and then a charter was obtained from him, not by the barons, but by the whole people of the realm in Parliament assembled. This is the charter which Hallam, and indeed all the legal historians, declare is the law of the land, John's charter never having been established. And now was seen, by the important additions made to this charter, the source from which it had proceeded. Its benefit was extended to Ireland: a new clause was added, ordering the destruction of every castle built or rebuilt since the commencement of the wars of John and his barons. All the forests which had been enclosed since the reign of Henry II. were thrown open, and the deadly forest laws which ordered a man's eyes to be put out for stealing a deer were abolished or reduced to mildness by a separate charter, called the Charter of the Forests.

Such is the history of Magna Charta. It was not till after a very protracted and sanguinary struggle that the people of England obtained the peaceable enjoyment of it.

Thus completely was the English race developed within less than a century and a half of the Conquest, and thus had they won that great triumph which has placed this country on a basis of freedom so far beyond every other nation in Europe.

Let us now take a brief survey of the progress of

THE CONSTITUTION AND THE LAWS

since that period. In narrating the events of the different reigns, we have already mentioned many of them, and may therefore content ourselves with a brief review. The privileges confirmed by Magna Charta to the various classes of English subjects may be divided into four sections. 1. Those to the Church. 2. Those to the barons and knights who held in capite, or directly from the king. 3. Those to cities and the trading community. 4. To all free men; for of the villeins or slaves no party whatever took the least notice.

Along with Archbishop Langton there were six other bishops who took an active part in procuring the charter, and, therefore, the Church was certain to have its interests well cared for. Henry II., by the Constitutions of Clarendon, had endeavoured to reduce the clergy to the same jurisdiction as all other British subjects, and to cut off the pernicious power of a foreign potentate over his subjects—that is, of the Pope. By these famous statutes all presentations to sees and livings wore to be made by the king, or with his consent. All clergymen guilty of civil offences were to be tried in the civil courts. Suits between a clergyman and layman wore to be tried in those courts. No clergyman was to leave the kingdom without the king's permission; a measure which precluded the common practice of clergymen going to Rome, and there getting causes determined in defiance of the king. Appeals from the archbishop were to be made not to the Pope, but to the king. All prelates who held baronies were to do service like the lay barons, and all vacant sees and abbeys were to belong to the king.

Out of these famous laws arose the great struggle with Thomas à Becket and the clergy. Had Henry maintained these ordinances, the English Church would have become as independent of the papal chair as it did under Henry VIII. But the time was not come, and Henry was compelled to succumb in the contest. The provisions of the charter now repealed the Constitutions of Clarendon; the Church was declared to be free; the clergy were at liberty to go out of the realm when they pleased; they and their benefices were removed from the civil jurisdiction, and they were not to be amerced according to their ecclesiastical benefices, but their secular estates.

The conditions of the feudal tenure were determined in favour of the barons, and their rates of payment fixed. The relief were sums paid when a baron, on coming at age, took up his right and paid his fee to the king. These reliefs had before been arbitrary, and had been in many cases monstrous. The king was the guardian of all his minor vassals, male and female, and had the management of their estates during their minority—a very profitable prerogative, and often farmed out to greedy and unprincipled men.

By the charter no waste was to be made on the estates, and no relief was to be paid on coming at age. The female wards had been compelled to marry whoever the king pleased, or to purchase exemption at a heavy cost. This was also a monstrous condition of things. Women were compelled to marry men that they loathed; they were, in fact, sold, for the crown made great profit of these marriages. Widows as well as maids were compelled to marry, whether they would or not. In King John's reign the Countess of Warwick had been compelled to pay £1,000, equal at least to £15,000 of our money, that she might not be forced to marry till she pleased. These cases were constantly occuring. The charter put a restraint on this hideous abuse. No woman was to be married without the approbation of her relatives; no widow obliged to marry, or pay anything for her inheritance or property, nor to leave her husband's house for forty days after his death, within which time her dowry must be assigned.

Before the charter—for the conditions of the former charters had grown to be quite disregarded—the kings levied as much as they pleased for aids; that is, money to marry the king's eldest son or daughter, or ransom himself; for soutages, moneys paid in lieu of serving personally in the king's wars; and tallages, or subsidies levied at will. No man could call anything he had his own. The charter limited these exactions, and also those made by the great vassals on their tenants in turn.

Cities and towns were to enjoy all their charters and privileges. All weights and measures were to be regulated by those of London. To restrain the abuses of purveyance three clauses were introduced. The cruelties and abuses of purveyance were amongst the most crying abominations of the feudal ages. Eadmer, who lived in the reign of Rufus, describes the atrocities of this practice; and that description would have held good for ages afterwards:—"Those who attended the court plundered and destroyed the whole country through which the king passed, without any control. Some of them were so intoxicated with malice that, when they could not consume all the provisions in the houses which they invaded, they either sold or burnt them. After having washed their horses' feet with the liquors they could not drink, they let them run out on the ground, or destroyed them in some other way. But the cruelties they committed on the masters of families, and the indecencies offered to their wives and daughters, were too shocking to be described."

These abominations the charter prohibited. No man's goods were to be taken without instant payment. His horses, carts, or wood were not to be taken at all without his consent.

No sheriff or bailiff of the crown was to hold pleas of the crown; that is, try for capital crimes, or inflict capital punishments—a great defence against arbitrary acts of officials in local posts. No freeman was to be seized or imprisoned, much less condemned and punished, except by judgment of his peers; and justice was neither to be withheld nor delayed—the last concession amounting to a writ of habeas corpus, and upon which that celebrated instrument of justice was founded.

Foreign merchants were to come and go at pleasure without molestation or fear, which they could not do before, being only allowed to remain in the country forty days, and to exhibit their goods at certain fairs. No judges were to be appointed except those learned in the law. The Court of Common Pleas was to be made stationary, and not to follow the king. The forest laws were ameliorated, and amercements, or penalties for legal offences, were limited. They were not to extend to a freeholder's freeholds, a merchant's merchandise, or a husbandman's implements of husbandry.

Such were the chief provisions of Magna Charta; and the various constitutional struggles and enactments which we shall have to notice from that time to our own were to expound and establish its principles in judicial forms.

One of the first effects of the charter was to regulate the courts of law. These, however, were by no means greatly improved till the reign of Edward I. In speaking of the transactions of his reign, we noted the groat constitutional acts of that wise monarch. Though the Court of Common Pleas, in conformity with Magna Charta, had been fixed at Westminster, where it still continues, yet it was not completely severed from the Court of Exchequer till 1300, when Edward I. enacted that "No common pleas shall be henceforth holden in the Exchequer, contrary to the form of the Great Charter."

About the same time the Court of King's Bench was also separated from the Exchequer; and although those who were summoned to attend the court were commanded to appear "coram ipso rege," before the king himself, and notwithstanding this was strengthened by a special statute passed in 1300, that this court should always follow the king, yet the obvious necessities of its business soon fixed it, with some temporary exceptions, at Westminster. The separate establishment of these two courts very much reduced the business and impaired the dignity of the Court of Exchequer. The Lord Chancellor used to sit as one of the judges of the Exchequer after the separation of the two courts of Common Pleas and King's Bench; but the Court of Chancery was of much slower growth.

About the same time that these useful changes took place, justices of assize and nisi prius were appointed to go into every shire two or three times a year, for the more prompt administration of justice; and these judges were made justices of gaol-delivery at all places in their circuits.

All these improvements, however, not keeping down the host of thieves, murderers, and incendiaries, Edward I. appointed what he called justices of traile-baston, who proceeded to all parts, and exercised severe jurisdiction over such felons; and, still further to extend order and protection, he appointed justices of peace—officials of such indispensable and daily use, that we wonder how society was carried on before this era. At the same time Edward abolished the office of high justiciary, as conferring too much power on any subject. He, moreover, kept a sharp eye on the judges and justices, and punished them severely for neglect or violation of their duties. On his return from France, in 1290, so many were the complaints of the rapacity and extortion of the judges, that he summoned a Parliament expressly to call them to account, where all the judges, except two, were found guilty, and heavily fined. Sir Thomas Wayland, the chief justice, was banished, and his estates confiscated.

We have already stated, in speaking of Edward I.'s reign, that he was the fist who regularly summoned the Commons to Parliament. Though this had been done in Henry III.'s reign by the Earl of Leicester—commonly called Leicester's Parliament—yet it had fallen again into disuse, and it was only restored by Edward I. on the just ground that what concerned all ought to be approved by all. Yet it does not appear that the Commons at this period possessed any separate house, though they occasionally retired and consulted on their own affairs. These were, chiefly, granting money and presenting petitions of grievances.

The clergy still formed an integral part of Parliament; the prelates, abbots, and priors corresponding to the lords; the deans and archdeacons to the knights of shires, who were summoned by the bishop as the knights were by the sheriff; and the representatives of the ordinary clergy corresponded to the representatives of boroughs, and were called the spiritual Commons. The clergy granted their money separate from the laity; and from this reign date the two houses of Convocation. The judges, also, still sat in Parliament.

Parliament assembled for the Deposition of Richard II.

From the Harleian MSS. 1319.

Siege of a Town in the Fourteenth Century.

In all that related to his own prerogative, however, Edward was very arbitrary, continually breaking the charter, exercising purveyances, and exacting taxes without consent of Parliament; and one of the worst evils of his reign was his empowering the nobles to entail their estates by a direct statute which has given the aristocracy of to-day its overwhelming and dangerous influence.

King and Armour-bearer. 13th Century.—Meyrick.

He passed the famous statute De tallagio cum concidendo, prohibiting the levy of tallages, or arbitrary imposition; but nobody paid less attention to the statute than himself.

The unsettled reign of Edward II. left the constitution pretty much as it found it; but in the following reign great progress was made. Edward III. had incessant demands for money to carry on his wars in Scotland and France; and, therefore, he was in the constant habit of calling together his Parliament. There remain no fewer than seventy writs of summons to Parliament and great councils issued during his reign. The difference between Parliaments and great councils at that time seems to be that in Parliament he required the Commons to grant taxes; in groat councils only the barons and great officers to consult on matters in which money-raising was not concerned.

In Edward III.'s reign Parliament resolved itself into three great elements—the Lords, the Commons, and the Clergy. In the Parliament which met in Westminster in 1339, the barons voted a tenth sheaf, fleece, and lamb; the knights objected to so large a contribution till they had consulted their constituents. This led to the knights of shires, who were representatives, meeting also with the Commons, who were representatives, and thus the representative house became separated from the hereditary house. It required time to amalgamate the two classes of knights and citizens in one house; the knights, as belonging to the aristocracy, looking down on the citizens, and they in their turn having a very humble idea of themselves; but we shall see that all that gradually corrected itself. The clergy now regularly voted their funds in Convocation, and no longer sat in the Commons by their proxies. It does not appear exactly when the judges ceased to sit ex-officio in Parliament, but they had ceased to do so in Richard II.'s time. In the forty-sixth of Edward III., practising lawyers were excluded by statute from Parliament, a position which they have since regained.

The knowledge of political economy possessed by Parliament in this famous reign was lamentably low. The topographical knowledge of the Commons was ludicrous. They granted the king, in 1371, £50,000, by a tax of 22s. 3d. on each parish, supposing the number of parishes to be about 45,000; but finding they were not one-fifth of that number, they had to alter the rate to £5 10s. per parish. But this was not a more amazing mistake than that of the English ambassador at Rome six years afterwards, who, finding that the Pope had created Lewis of Spain prince of the Fortunate Islands, meaning the Canary Isles, immediately hurried homo with all his suite to convey the alarming news that the Pope had given the British Isles to the King of Spain! The statute books of this famous king show the most absurd endeavours to disturb the freedom of trade, betraying as little knowledge of the principles of political economy as our own legislators on the corn laws. Wishing to raise a manufacturing system, it was forbidden to import woollen cloths before we could supply the people with home-made goods. Money was prohibited from being carried out of the country. They were obliged to let in foreign cloth, or the people would soon have been naked; yet after awhile they prohibited it again. A famine having taken place, they passed an act to keep down the price of all articles of food; the consequence of which was, nobody would bring any such articles to market; and they were compelled to abolish that. Then they did the same thing by labour, fixing the rate of wages; and yet when Wat Tyler's party in the following reign wanted to regulate the price of land, the attempt was pronounced barbarous.

In this reign an act was passed ordering all pleas to be conducted in English and enrolled in Latin, they having been hitherto, since the Norman Conquest, chiefly conducted and enrolled in Norman-French, which was quite an unknown tongue to the bulk of the common people. The statutes, however, had been recorded in Latin till 1206, when they began to be written in French. This took place at Winchester in some statutes concerning the exchequer, and not in the statute of Westminster in 1675, as asserted by some historians. The practice of pleading in French was not uniform in the reign of Edward I., but became more and more, till in Edward III.'s reign it was almost exclusively used. In the same Parliament of Winchester there were penalties enacted against the extortions of bakers and brewers. The bakers were punished by the pillory; the brewers, who, it appears, were all women, by the ducking-stool. The wars with France had now created an anti-French feeling, and so far tended to develop the English language as well as spirit, and make it the language of all classes.

13th Ceutury. Ciborium, in the Collection of Prince Soltykoff, at Paris.

The reign of Richard II. is distinguished constitutionally by the more regular and established separate assembling of the two Houses of Parliament, and by the rapidly rising power of the Commons. This house had now its duly appointed speaker, Sir Peter de la Mare being particularly noted in that office, and the Commons proceeded to impeach the king's ministers for maladministration. Having, however, given the king supplies for life, the Commons lost its influence, became servile and debased, and led more than anything to the deposition and destruction of the monarch.

During the period now under review, Wales was added permanently to England by Edward II., and its laws and constitution made identical. The laws of Scotland, also, during this time were very similar to those of England. The great Robert Bruce, after his power was established by the battle of Bannockburn, summoned a Parliament, which met at Scone, in 1319, and passed a capitulary, or collection of statutes; and in 1328 a second system or capitulary was passed, consisting of thirty-eight chapters. Many of these are clearly framed from the English statutes of Henry III. and Edward I., and some of them are transcribed almost verbatim; a proof of the wisdom and magnanimity of Bruce, who did not disdain to benefit by the good laws of an enemy. The Parliament held at Cambuskennoth, in 1326, included not only burgesses, but all the other freeholders of the kingdom. In a word, so great was the resemblance between the laws and constitutions of the two countries during this period, that it is not necessary to note the minor differences. The Parliament of Scotland never divided itself into Lords and Commons.

It is difficult to ascertain the annual revenues of the crown in those ages. That of Henry III. is stated at 60,000 marks, or £40,000; and that of Edward III., at £150,000; and taking those sums at ten times their present value, the revenue of Henry III. must be equivalent to £100,000 now, and Edward III.'s to £1,500,000. If, however, we recollect the enormous and regular exactions of those ages, especially on the Jews, the expenditure of the crown must have been immensely larger.

POWER OF THE CHURCH.

Between the reign of John and the termination of that of Richard II. a striking change had taken place in the power of the Church in England. From the zenith of that marvellous dominion over the kingdoms of this world, such as no Church or religion had yet exercised in the annals of mankind, it had begun sensibly to wane. From that extraordinary spectacle when, at Torcy, on the Loire, in 1162, the two greatest kings of Christendom, those of England and France, wore seen holding the stirrups of the servant of servants, Alexander III., and leading his horse by the reins, to the day when John, just half a century afterwards, laid the crown of this fair empire at the feet of the Pope, "and became a servant unto tribute," everything had seemed to root the Papacy deeper into the heart of the world. Kings, nobles, and people bowed down to it, and received its foot on their necks with profound humility, only occasionally evincing a slight wincing under its exactions. At that period the Church of Rome had reached the summit of its glory;

Crozier, 13th Century. In the Collection of Prince Solfykoff, at Paris.

but before the era at which we have now arrived it had received a stern warning that its days in this country were numbered as the established hierarchy. So long as the people were kept ignorant of the Bible, the opposition of king or peer mattered little to it; but the people withdrew their allegiance, and it fell rapidly.

The Pope, who strenuously supported John against his barons, was equally friendly to his infant son, Henry III. Cardinal Langton, now in the ascendant, held a synod at Oxford in 1222, in which fifty canons were passed, some of which let in a curious light on the internal condition of the Church. The twenty-eighth canon forbids the keeping of concubines by the clergy openly in their houses, or visiting them openly, as they did, to the great scandal of religion. In 1237 a council was held at London by Otho, the Papal legate, in which were passed what were afterwards known as the "Constitutions of Otho." The fifteenth and sixteenth canons of this constitution were aimed at the same practices, and at clandestine marriages of the priests, which were declared to be very common.

Costume of a Bishop of the 14th Century.

But the great object of the Church was to collect all the English moneys, and in this pursuit there was no slackness. A cardinal legate generally resided in this country, whose chief function this was. During Otho's abode here, 300 Italians came over, and were installed in lucrative livings in the churches and abbeys. In pursuance of Magna Charta, that the Church should be free, it became the only free thing in the kingdom; every class of men were its vassals, and England was one great sponge which the Italian pontiff squeezed vigorously. The barons in 1245 became so exasperated that they sent orders to the wardens of the sea-ports to seize all persons bringing bulls or mandates from Rome. The legate remonstrated, and the barons there told the king that the Church preferments alone held by Italians in England, independent of other exactions, amounted to 60,000 marks per annum, a greater sum than the revenues of the crown. The barons went further; they sent an embassy to the Papal council of Lyons, where the Pope was presiding in person, when they declared, "We can no longer with any patience bear these oppressions. They are as detestable to God and man as they are intolerable to us; and, by the grace of God, we will no longer endure them."

Effigy of Jocelyn, Bishop of Salisbury. From a Tomb in Salisbury Cathedral.

But, so far from relaxing his hold, the Pope soon after sent an order demanding the half of all revenues of the non-resident clergy, and a third of those of the resident ones. This outrageous attempt roused the English clergy to determined resistance, and the rapacious Pope was defeated. Amongst the most patriotic of the English prelates was the celebrated Robert Grosteste, or Grosted, or literally Greathead, Bishop of Lincoln. Innocent IV., one of the most imperious pontiffs that ever filled the Papal chair, had sent Grosted a bull containing a clause which created a wonderful ferment in the Church and the public mind, commencing with the words Non obstante, which meant, notwithstanding all that the English clergy had to advance, the holy father was determined to have his will, and he commanded the venerable bishop to bestow a benefice upon an infant. The honest bishop tore up the bull, and wrote to the Pope, declaring that the conduct of the see of Rome "shook the very foundations of faith and security amongst mankind," and that to put an infant into a living would be next to the sins of Lucifer and of Antichrist, was in direct opposition to the precepts of Christ, and would be the destruction of souls by depriving them of the benefits of the pastoral office. He refused to comply, and said plainly that the sins of those who attempted such a thing rose as high as their office.

The astonished Pope was seized with a furious passion on receiving this epistle, and swore by St. Peter and St. Paul that he would utterly confound that old, impertinent, deaf, doting fellow, and make him the astonishment of the world. "What!" he exclaimed, "is not England our possession, and its king our vassal, or rather our slave?"

The resistance of the English clergy only inflamed the cupidity and despotism of the pontiffs. Boniface, the Archbishop of Canterbury, was the servile tool of Rome, and after him Kilwarby, Peckham, and Winchelsey, carried things with a high hand. At various synods and councils held at Merton, Lambeth, London, Reading, and other places, they passed canons, which went to give the Church unlimited power over everything and everybody. The Church was to appoint to all livings and dignities; no layman was to imprison a clergyman; the Church was to enjoy peaceably all pious legacies and donations. The barons wrote to the Pope, remonstrating and complaining against the immorality of the clergy. The Pope replied that he did not suppose the English clergy were any more licentious than they had always been. The possessions of the Church went on growing to such an extent, from the arts of the priests and superstition of the wealthy, that they are said to have amounted to three-fourths of the property of the whole kingdom, and threatened to swallow up all its lands. To put a stop to this fearful condition of things, Edward I. passed his famous statute of mortmain in 1279, and arrested the progress, for a considerable time, of the Papal avarice.

But, perhaps, the finest draught of golden fishes which the imperial representative of Peter of Galilee ever made in England, was twenty-five years before the passing of this act, when he had induced Henry III. to nominate his son Edmund to the fatal crown of Naples, and, on pretence of supporting his claim, the Pope drew from England, within a few years, no less a sum than 950,000 marks, equal in value and purchasable power to £12,000,000 sterling of our present money.

Fac-smile of Part of the First Chapter of St John's Gospel, in Wycliffe's Bible.

Boniface VIII., famous in his day as the most haughty and uncompromising of the Popes, issued a bull prohibiting all princes, in all countries, levying taxes on the clergy without his consent. Winchelsey, Archbishop of Canterbury, produced this bull, and forbad Edward I. to touch the sacred patrimony of the Church. But Edward was a monarch of the true British breed, and soon proved himself more than a match for the archbishop and his Roman master. He held a Parliament at Edmondsbury, in 1296, and demanded a fifth of the movables of the clergy. They refused. Edward gave them till the next Parliament, in January, 1297, to consider of it, when, still refusing, and supposing themselves victorious, the king coolly told them that, as they refused to contribute to the support of the state, they should enjoy no protection from the state. He forthwith outlawed them in a body, and ordered all the sheriffs in England "to seize all the lay fees of the clergy, as well secular as regular, with all their goods and chattels, and retain them till they had further orders from him." He gave orders to all the judges, also, "to do every man justice against the clergy, but to do them justice against no man."

This was a state of things which they had never expected; no monarch had ever dreamt of, or had dared to attempt such a measure. It came like a thunder-clap upon the clergy. They found themselves insulted, abused, and plundered on all sides. The archbishop himself, the author of all this mischief, was stripped of everything, and on the very verge of starvation, and was glad to submit and pay his fifth to recover the rest of his property.

The power of the Popedom had thus been brought into collision with the royal prerogative and the issue was such as was most damaging to the Papal prestige all over the world. But Winchelsey, having regained his possessions, was too indignant to remain quiet. He held a second synod at Merton, and denounced the utmost terrors of the Church against all sacrilegious invaders of the Church property, and would not rest till Edward obtained his suspension from the next Pope, Clement, and expelled him the kingdom.

Those contests betwixt the civil and ecclesiastical power in England continued through the whole period we are reviewing, that is, from 1307 to 1399, or from the commencement of the reign of Edward II. to the end of that of Richard II. To increase the influence of Rome there had arrived two new orders of friars, the Franciscan and Dominican, in the reign of Henry III. The Franciscans appeared in England in 1216, and the Dominicans in 1217. Before their arrival the country swarmed with monks, but these were styled mendicant friars, as devoted to a species of holy beggary. But, in 1311, in the early part of the reign of Edward II., the Church suffered a great defeat by the overthrow and annihilation of the famous military order of Knights Templars. To prevent the Pope thrusting foreigners into the English prelacies and benefices, Edward III. passed a second statute of provisors, and followed it by the statute of premunire, ordering the confiscation of the property and the imprisonment of the person of every one who should carry any pleas out of the kingdom, as well as of the procurators of such person; and this was again renewed in 1392 with additional severity by Richard II., including all who brought into the kingdom any Papal bull, excommunication, or anything of the kind.

Eight years prior to this Wyclifie died. His doctrines were rapidly spreading; the reformers, under the name of Lollards, were becoming numerous; the Papal hierarchy was proportionally alarmed, and Arundel,

Author, and Copyist writing.

From a Miniature of the Romance, "L'Image du Monde," MS. 7070, fol. i., in the Imperial Library of Paris.

the Archbishop of York, became their most active enemy. But before he could mature his designs against them, he was involved in the prosecution of the adherents of the Duke of Gloucester for procuring a commission to control the king, for which his brother, the Earl of Arundel, was beheaded, and he himself banished. The dawn of the Reformation already reddened in the east, but the day was yet far off.

During the fourteenth century, the leading men of the Church in Scotland distinguished themselves rather in the patriotic defence of their country against the English, than in theological matters. Amongst the most distinguished of these were Lambeton, of St. Andrews, Wishart, of Glasgow; Landells, who was Bishop of St. Andrews from 1311 to 1035, forty-four years; and Dr. Robert Trail, Primate of Scotland, who built the castle of St. Andrews, and died in 1401, leaving a great name for strict discipline and wisdom. It is singular that, during this period, the doctrines of "Wycliffe, which had made such a ferment in England, appear to have excited little or no attention in Scotland.

LITERATURE, SCIENCE, AND ART.

During the period now under review, the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the language of the learned was still Latin, and the circle of education still included little more than the Trivium and Quadrivium of the former age, that is, the course of three sciences—grammar, rhetoric, and logic; and the course of four—music, arithmetic, geometry, and astronomy. The grammar was almost exclusively confined to the Latin, for Roger Bacon says that there were not more than three or four persons in his time that knew anything of Greek or the Oriental languages; nay, so gross was the ignorance of the students of the time of the common elementary forms of Latin itself, that Kilwarby, Archbishop of Canterbury, on a visit to Oxford in 1276, upbraided the students with such corruptions as these:—"Ego currit; tu currit; curren est ego," &c.

Roger Bacon.

When grammar was so defective the rhetoric taught could not be very profound. The mendicant friars seem to have cultivated it with tho greatest assiduity, as necessary to give effect to their harangues, and Bederic de Bury, provincial of the Augustinians, in the fourteenth century, was greatly admired for the eloquence of his preaching.

But logic was the all-absorbing study of tho time. The clergy who had attended the Crusaders had brought back from the East a knowledge of Aristotle, through Latin translations and the commentaries of his Arabian admirers. His logic was now applied not only to such metaphysics as were taught, but also to theology. Hence arose the school divinity, in which the doctrines taught by the Church were endeavoured to be made conformable to the Aristotelian modes of reasoning, and to be defended by it. If we are to judge of the logic of this period by what remains of it, we should say it was the art of disputing without meaning or object; of perplexing the plainest truths, and giving an air of plausibility to the grossest absurdities. As, for instance, it was argued with the utmost earnestness that "two contrary propositions might be both true." At this time there were no less than 30,000 students at Oxford, and Hume very reasonably asks, what were these young men all about? Studying bad logic and worse metaphysics.

The metaphysics of these ages were almost engrossed by the great controversy of the Nominalists and the Realists; the question, agitated with all the vehemence of a matter of life and death, being, whether general ideas were realities, or only the particular ideas of things were real. The Nominalists declared that a general idea, derived from comparing a great number of individual facts, was no reality, but a mere idea or name; the Realists contended that these general ideas were as absolute actualities as the individual ones on which they were based. Rocelln of Compiegne revived this old question at the end of the eleventh century, and thus became the head of the schoolmen of those ages; but William of Ockham, in the fourteenth century, again revived this extraordinary question with all its ancient vehemence, his partisans acquiring the name of Ockhamists. Ockham was a Nominalist, and, says an old historian, he and his party "waged a fierce war against another sect of schoolmen, called Realists, about certain metaphysical subtilties which neither of them understood."

Moral philosophy could not be much more rationally taught when metaphysics and logic were so fantastic. Many systems of moral philosophy were taught by the schoolmen, abounding in endless subtle distinctions and divisions of virtues and vices, and a host of questions in each of these divisions. By the logic, metaphysics, and moral philosophy of the schoolmen combined, the most preposterous doctrines were often taught. For instance, Nicholas de Ultricuria taught this proposition in the University of Paris in 1300:—"It may be lawful to steal, and the theft can be pleasing to God. Suppose a young gentleman of good family meets with a very learned professor (meaning himself), who is able in a short time to teach him all the speculative sciences, but will not do it for less than £100, which the young gentleman cannot procure but by theft; in that case theft is lawful—which is thus proved: Whatever is pleasing to God is lawful. It is pleasing to God that a young gentleman learn all the sciences, but he cannot do this without theft; therefore theft is lawful, and pleasing to God."

It was high time that something tangible and substantial should come to the rescue of the human mind from this destructive cobwebry of metaphysics; and the first thing which did this was the study of the canon law. The civil and the canon laws not only gave their students lucrative employment as pleaders, but wore the road to advancement in the Church. The clergy in these ages were not only almost the only lawyers, but also the doctors, though some of the laity now entered the profession as a distinct branch. "The civil and canon laws," says Robert Holcot, a writer of that time, "are in out days so exceedingly profitable, procuring riches and honours, that almost the whole multitude of scholars apply to the study of them."

What was the real knowledge of the science of medicine at this period we may imagine from the great medical work of John Gaddesden, who was educated at Merton College, Oxford, and declared to be the grand luminary of physic in the fourteenth century. "He wrote," says Leland, "a large and learned work on medicine, to which, on account of its excellences, was given the illustrious title of the 'Medical Rose.' This is a recipe in the 'Illustrious Medical Rose' of Gaddesden for the cure of small-pox:—'After this (the appearance of the eruption), cause the whole body of your patient to be wrapped in red scarlet cloth, or in any other red cloth, and command everything about the bed to be made red. This is an excellent cure. It was in this manner I treated the son of the noble King of England, when he had the small-pox, and I cured him without leaving any marks.'"

The royal patient thus treated must have been Edward III., or his brother. Prince John of Eltham.

To cure epilepsy Gaddesden orders the patient "and his parents" to "fast three days and then go to church. The patient must first confess, he must have mass on Friday and Saturday, and then on Sunday the priest must read over the patient's head the Gospel for September, in the time of vintage, after the feast of the Holy Cross. After this the priest shall write out this portion of the Gospel reverently, and bind it about the patient's neck, and he shall be cured."

That is a sample of the practice of medicine from the great work of the great physician of the age. As to the surgery of the time, it is thus described by Guy do Cauliac, in his "System of Surgery," published in Paris in 1363:—"The practitioners in surgery are divided into five sects. The first follow Roger and Roland, and the four masters, and apply poultices to all wounds and abscesses. The second follow Brunus and Theodoric, and in the same cases use wine only. The third follow Saliceto and Lanfranc, and treat wounds with ointments and soft plasters. The fourth are chiefly Germans, who attend the armies, and promiscuously use potions, oil, and wool. The fifth are old women and ignorant people, who have recourse to the saints in all cases."

It was high time that a man like Roger Bacon should appear, and teach men to come out of all this jugglery and mere fancy-work both in science and philosophy, and put everything to the test of experiment—a mode of philosophising, however, which made little progress till the appearance, three centuries later, of another Bacon, the great Verulam. For the knowledge of geometry, arithmetic, astronomy, and chemistry—or rather astrology and alchemy—as taught at that period, we may refer to our notice of Bacon amongst the great men of the era.

But the number of schools and colleges which were erected during this period, are a striking proof that the spirit of inquiry and the love of knowledge was taking rapid and deep root in the nation. In Oxford alone seven colleges were founded during this period. University Hall or College was founded by King Alfred, but its foundation was overturned and its funds dissipated long before this period. "William, Archdeacon of Durham, who died in 1219, bequeathed 31 marks to the university, and may be considered the founder of this college: his money was expended for this purpose. Baliol College was founded by John Baliol, the father of John the King of Scotland, about 1268, and completed by the Lady Devorgilla, his widow. Merton College was founded by Walter Morton, Bishop of Rochester, in 1268. Exeter College was founded by Walter Stapleton, Bishop of Exeter, and Peter de Skelton, a clergrymn, in 1315. It was first called Stapleton College. Oriel College was founded by Edward II., and his almoner, Adam de Brun, about 1342, and was called the Hall of the Blessed Virgin of Oxford, but derived its permanent name from a fresh endowment by Edward III. Queen's College was founded by Robert Englefield, chaplain to Philippa, queen of Edward III., and named in her honour because she greatly aided him in establishing it. New College was named St. Mary's College by its builder and founder, William of Wykeham, who also built one at Winchester. It was finished in 1336.

Matthew Paris. From a Drawing by Himself in Royal MS., Nero, D. 1.

In Cambridge, during this period, were founded nine colleges, namely:—Peter House was founded by Hugh Balsham, afterwards Bishop of Ely, about 1282. Michael College, dedicated to St. Michael, was founded and endowed about 1324, by Harvey de Stanton, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Edward II. University Hall was founded by Richard Badew, Chancellor of the University, in 1326, but was soon after destroyed by fire. King's Hall was built by Edward III., but afterwards united to Trinity College. Clare Hall was a restoration of University Hall, by Elizabeth de Clare, Countess of Ulster, and named in honour of her family. Pembroke Hall was built by Mary de St. Paul, 1347, widow of Aymer de Valence, Earl of Pembroke, in memory of her husband, who was killed in a tournament soon after their marriage. She named it the Hall of Valence and Mary. Bennet College was founded near the same time by the united guilds of Corpus Christi and St. Mary, assisted by Henry Duke of Lancaster. Trinity Hall was founded about 1350, by William Bateman, Bishop of Norwich. Gonvil Hall was founded by Edward Gonvil, parson of Terrington and Rushworth in Norfolk, about the same time as Trinity was built.

These were for the most part small and simple establishments at first, but have arrived at their present wealth and magnificence by additional benefactions.

The numbers of scholars who rushed into those schools at first was something extraordinary; nor were their character and appearance less so. They are described by Anthony à Wood as a regular rabble, who wore guilty of theft and all kinds of crimes and disorders. He declares that they lived under no discipline nor any masters, but only thrust themselves into the schools at lectures, that they might pass for scholars when they were called to account by the townsmen for any mischief, so as to free them from the jurisdiction of the burghers. At one time, according to Fitz-Ralph, the Archbishop of Armagh, there were no loss than 30,000 students—or so-called students—in Oxford alone; but he says that they were again reduced to less than 6,000, so many of them had joined the mendicant friars.

Such was the disorder of the two universities at this time, the violent quarrels, not only betwixt the students and the townspeople, but also betwixt each other, that many of the members of both universities retired to Northampton, and, with the permission of Henry II., commenced a new university there; but the people of Oxford and Cambridge found means to obtain its dissolution from the king. About thirty years afterwards they tried the same experiment at Stamford, but were stopped in the same manner.

London at this time so abounded with schools, that it was called the third university. Edward III. built the college of St. Stephen at Westminster for a college of divinity, which was dissolved by Henry VIII. bishop Bradwardine founded a theological lecture in St. Paul's Church, and John of Gaunt founded a college for divines in St. Paul's churchyard. There were various schools besides these, but the most remarkable were the great schools of law, which arose out of the provisions of the Great Charter, which fixed the chief courts of justice at Westminster. Sir John Fortescue, who studied in one of these inns of court, describes them as a great school or university of law, consisting of several colleges. "The situation," he says, "where the students read and study is between Westminster and the City of London. There belong to it ten lesser inns, and sometimes more, which are called the inns of Chancery, in each of which there are a hundred students at least, and in some of them a far greater number not constantly residing." In these the young nobility and gentry of England began to receive some part of their education, so that with all these colleges of learning and of law, the laity as well as the clergy began to reap the benefits of education.

MEN OF LEARNING AND SCIENCE.

Amongst the theologians of this period, none surpass for extent of learning, talent, and eloquence, Robert Grosteste, or Greathead, Bishop of Lincoln. He was originally a very poor lad; but the Mayor of Lincoln, noticing his quickness of faculty, took him into his house and put him to school. He studied at Oxford, Cambridge, and Paris, his splendid talents acquiring him many patrons. Bacon, who knew him well, gives this testimony of him:—"Robert Greathead, Bishop of Lincoln, and his friend. Prior Adam do Marisco, are the two most learned men in the world, and excel all the rest of mankind both in divine and human knowledge."

Greathead was one of the very few real Greek scholars of the age, and was equally versed in Hebrew, French, and Latin. But, beyond his learning, which he has embodied in many voluminous works, his noble and independent character stands pre-eminent in those times. We have mentioned his opposition to the Pope inducting mere infants into church livings; and the caution which tho cardinals are reported, by Matthew Paris, to have given the Pope when he threatened to take vengeance on him, is remarkable, as indicating their knowledge of the tendency of the age. "Let us not raise a tumult in the Church without necessity, and precipitate that revolt and separation from us which we know must one day take place."

But the man of that time in philosophy was Roger Bacon, as Chaucer was in literature. Bacon was born near Ilchester, and educated at Oxford, and afterwards at Paris. On his return to England, at the age of twenty six, he again settled at Oxford, and entered the order of Franciscan friars of that city, that he might study at leisure. He soon abandoned the beaten track, and struck out a course of inquiry and experiment for himself. He was not content to study Aristotle alone at second hand, but he made himself master of Greek, and went to the fountain head of ancient knowledge.

But that did not satisfy him. He sought to make himself acquainted with Nature, the groat fountain of all our human knowledge. He declared that if you would know the truth you must seek it by actual inquiry and experiment. In this system, of philosophising he preceded Francis Bacon nearly three centuries and a half; but he was before his time, and, therefore, the benefit of his teaching was, to a great degree, lost. His great work, the "Opus Majus," contains the result of his researches; and he states in that work that he had expended £2,000 in twenty years on apparatus and experiments—a sum equal to £30,000 of our money at present. This he had done through the generosity of his friends and patrons, having made a greater amount of discoveries in geometry, astronomy, physics, optics, mechanics, and chemistry, than ever were accomplished by any one man in an equal space of time. In his treatise on optics, "De Scientia Perspectiva," he gives you the mode of constructing spectacles and microscopic lenses. In mechanics, he talks of having ascertained by experiments wonders that we have not yet reached by steam; of a mode of propelling ships so that they should require only one man to guide them, and with a velocity greater than if they were full of sailors. "Chariots," he says, "may be constructed that will move with incredible rapidity, without the help of animals." He speculated and believed in the capability of raising the most wonderful weights by mechanical contrivance, and of walking on the bottom of the sea. But, unfortunately, he has not left us the explicit exposition of these marvels. His system of chemical analysis has, however, been greatly praised by some modern chemists, and it is evident that he was well acquainted with gun-powder. "A little matter," he says, "about the bigness of a man's thumb, makes a horrible noise, and produces a dreadful corruscation; and by this a city or an army may be destroyed several ways." He then explains that sulphur, saltpetre, and powdered charcoal are the ingredients of this wonderful explosive substance. Whether Bacon discovered this mixture, or whether he learnt it in his Asiatic reading, has been a query. At all events, he knew the fact, and in the reign of Edward III. gun-powder came into use in war.

Bacon was the martyr of science. Instead of benefiting by his discoveries, the ignorant monks of his order accused him of necromancy and dealing with the devil. He was kept in close confinement for years, and he was not allowed to send his "Opus Majus" to any one except the Pope. After receiving a copy of it, Clement IV. procured him his liberty, but he was very soon imprisoned again by Jerome de Esculo, general of the Franciscan order. He continued in confinement this time eleven or twelve years, and, on coming out, old and broken down by his cruel suffering, he still continued his labours with undiminished ardour till his death in 1292.

A kindred spirit to Bacon was Michael Scott, who was born about the beginning of the thirteenth century at his family seat in Scotland. By his study of astrology and alchemy, in common with Bacon and the great inquirers of the time, he obtained the reputation of a magician, which has mixed up his name with the wildest popular legends and superstitions of Scotland. So strong were the convictions of his countrymen that he was a magician, that Dempster assures us many people in Scotland in his time dared not so much as touch his works. Bishop Tanner says, "He was one of the greatest philosophers, physicians, and linguists of his age; and, though his fondness for astrology, alchemy, physiognomy, and chiromancy made people think him a magician, none speaks or writes more respectfully of God and religion than he does."

Hie was deeply read in the Greek and Arabic languages, and, while residing at the court of the Emperor Frederick II., he translated for that prince the works of Aristotle into Latin, to which Bacon attributes the high administration which those works obtained afterwards in Europe.

Duns Scotus, though supposed to be of Scotch origin, was educated at Oxford, from which seat of learning he went to Paris, to maintain before the university of that city his favourite doctrine of the immaculate conception of the Virgin. He had profoundly studied moral philosophy, mathematics, civil and canon law, and school divinity. No man of his age was so admired and applauded, but his works now sleep, covered with the dust of ages.

William of Ockham was a very learned and eloquent theologian, who maintained the temporal independence of kings, and was supported, against all the efforts of three successive Popes to crush him, by his patron the Emperor Ludwig of Germany; but, on the death of that prince, he was compelled to recant. He did not long survive this humiliation, having for many years borne the title of the Singular and Invincible Doctor. During his life appeared Wycliffe, who, under happier auspices, proclaimed the freedom of religion.

The historians of this period, from whom, and from the parliamentary writs and statutes, our history is derived, are chiefly those:—

Matthew Paris has been greatly quoted as a high authority from the earliest times to the year 1273, or to the end of the reign of Henry III. Matthew Paris, however, on inspection, divides himself into three persons, all monks of St. Albans, namely, Roger Wendover, Matthew Paris, and William Rishanger. Matthew Paris's own share comprehends only the period from 1235 to 1259, about twenty-five years. He continues Wendover, and Rishanger continues him. The work of Matthew Paris is the "Historia Major." Besides this he wrote the lives of Offa I. and II., and of twenty-three abbots of St. Alban's. Wendover's chronicle, "Flores Historiarum," reaches from the Creation to the year 1238, and is divided at the birth of Christ into two halves. Matthew Paris, in copying Wendover, has taken care to infuse here and there his own spirit, which was one of great freedom of remark on kings, priests, popes, and, what is singular, on the usurpations of the Court of Rome itself. Matthew had seen the world and courts, and had picked up a great quantity of amusing anecdotes and curious characteristics of great men. He went as ambassador of Louis IX. to Hacon of Norway, and, at the Pope's instance, made a visitation of the monastery of Holm, in that kingdom. He was employed in writing history by Henry III., and even assisted by him in it. He says, "He wrote this almost constantly with the king in his palace, at his table, and in his closet; and that prince guided his pen in writing in the most diligent and condescending manner." No historian who has written of his own times has shown more boldness and independence than Matthew Paris. Though a monk, he did not hesitate to paint the corruptions of a monastic life in the most plain colours, nor to denounce the corruptions of the Church and hierarchy at large with equal honesty. For this he has been assailed, and charged even with interpolating falsehoods by those whom his honest freedom had offended. But Matthew Paris was not only a most accomplished man for that age, but one of the most uncorruptible of those who ever associated with kings and pontiffs. He is declared at the same time to have been "famous for the purity, integrity, innocence, and simplicity of his manners."

Matthew Westminster copied Matthew Paris's "Flowers of History," which had not then been printed.

Thomas Wykes wrote a chronicle extending from the Conquest to 1304. He was a canon in the Abbey of Osney. The latter years of his chronicle, from 1293, are supposed to be by another hand.

Walter Hemmingford, a monk of the Abbey of Gisborne, in Yorkshire, wrote a chronicle of about the same period with Wykes, ending 1347. John de Trokelowe and Henry de Blandford, who are supposed to have been monks of St. Alban's, wrote histories of Edward II., as did also the anonymous monk of Malmsbury.

Bartholomew Cotton, whose work still remains unprinted in the Cotton MS., has copied other chronicles in his earlier pages; but the reign of Edward I. to the year 1298 is a very valuable contribution to our history.

Robert Avesbury, who was registrar of the court of the Archbishop of Canterbury, wrote the history of Edward III. to the year 1356. His account is most valuable. He gives us many particulars that appear nowhere else, which, as he had access to the best sources, are undoubtedly correct. They serve us to test the accounts of Froissart, who is apt to merge into the romantic. In this work of Avesbury's abound original letters of Edward regarding the attack on Cambray in 1336; the expedition into Brittany in 1342; relations of the circumstances which led to the battle of Creçy by officers and eye-witnesses, and despatches from the camps of the Earl of Derby and the Black Prince; with similar most interesting and invaluable documents.

Adam de Murimath wrote the history of Edward II. and the earlier part of that of Edward III. He was engaged much in public affairs as ambassador, both from the clergy to the Pope at Avignon, and from the king to the Court of Rome, as well as afterwards to the King of Sicily on account of Edward's claims in Provence. He saw much, and, as professor of civil law, was much engaged in affairs of the Government, but his account is somewhat meagre and dry.

Besides these we may name Nicholas Trivet, who wrote "Annals," from 1130 to 1307. Ralph Higdon, whose "Polychronicon" ends in 1357, and has been translated into English by John de Trevisa. Robert de Brunne, or Manning, a canon of Brunne, in Lincolnshire, wrote a rhymed chronicle, including versions or appropriations of Ware's old French poem of Brut, and Peter Langtoft's French" Rhymed Cronicall." The latter part, from King Ina to the death of Edward I., has some historic merit. Henry Kuyghton, a canon of Leicester, is the author of a history from the time of King Edgar to 1395, and of an account of the deposition of Richard II. His work is of great authority in the latter of these reigns. Thomas de la Moor wrote a life of Edward II., and asserts that he had the account of the battle of Bannockburn and Edward's last days from eye-witnesses.

In Scottish history of this period, we have the "Scalacronica," of Sir Thomas Gray of Heton, who was a native of the north of England, being taken prisoner by the Scots. He has left us in his "Cronicall" many particulars of the times of Wallace. Andrew Wyntown, the author of the "Orygynale Cronykil of Scotland," was living in the long reign of David II., and his rhymed chronicle reaches from the beginning of the world, in the fashion of those times, to the year 1424. He was canon of the priory of St. Andrew.

The portion of his chronicle from the beginning of the reign of David II. to the end of Robert II., is supposed to be by another hand. John Fordun's "Scotichronicon" is a regular chronicle of Scotland to the year 1385. This work was continued by Walter Bower, abbot of St. Columkil in the fifteenth century.

Besides these the monastic registers of Mailros, ending in 1270; of Margan, ending 1232; of Burton, ending 1262; and Waverley, ending 1291, afford evidence of the history of Scotland and England, and of the literary talent of the two countries at this time.

But it is to the poets of this era that we must look for the chief genius, and the evidences of the progress of literature in the nation. It is a singular fact, that while the Roman Church had continued the use of the Latin language during the Middle Ages, it had neglected, or rather discouraged, the reading of the great Roman and Greek writers, so that the Greek and Roman classical literature became, as it were, extinct. The great classical authors which were not destroyed, lay buried in the dust of abbeys and monasteries. So completely was Greek literature and the Greek forgotten, that, as we before stated, we find Bacon declaring that there were not above four men in England who understood Greek, or could pass the fifth proposition of the first book of Euclid—the familiar pons asinorum, or bridge of asses. So utterly were the clergy unacquainted with Greek that, on finding a New Testament amongst the books of the Reformers, they declared that it was some new heretical language. But, as knowledge revived, the same men who were the greatest advocates for classical studies and the restoration of the classical writers to public use, were those who began also to write in their vernacular tongues; and this was especially the case with Petrarch in Italy.

The Queen's Cross, Northhampton.

Latin was the almost universal language of the learned in art, science, and literature still at this period. The works of the chroniclers were written in Latin for the most part; Bacon wrote all his works in Latin. But for some time, in all the great countries of Europe, eminent authors—and especially the poets—had begun to use their native tongues. Dante, Boccaccio, and Petrarch in Italy had set the example; Froissart had done it in French; and now our great poets in England did the same.

This was a proof that the English language was now travelling up from the common people, and establishing itself amongst all ranks. It was no longer left to the common people to speak Anglo-Saxon, now fast melting in English. The Norman nobles and gentry found themselves speaking English, and engrafting on it many of their own terms. Metrical romances and songs had long been circulated amongst the people; they now reached the higher classes. Robert of Gloucester versified the chronicle of Robert of Monmouth; Peter Langtoft, a canon of Bridlington, found his chronicle in French verse translated into English by Robert Manning, of Brunne, already mentioned. This was the English of that day:—

"Pers of Langtoft, a chanon,

Schaven in the house of Bridlyngton,

O Frankis style this storie he wrote,

Of Inglis kinges," &c.

But about the middle of the fourteenth century Robert Langlande, a secular priest of Oxford, wrote a famous satirical allegory against persons of all professions, called "The Vision of Pierce Plowman." This is usually considered the first English poem, but it is rather an Anglo-Saxon one, for the author, probably very Saxon in his feelings, has not only imitated the alliterative poetry of the Saxons without rhyme, but he has made the language as antique as possible This is precisely what Spenser did in his "Faery Queen," in the reign of Elizabeth; he went backwards in his diction, so that now it is nearly obsolete, while the language of his contemporary Shakespeare is still sterling English, and likely to continue so. Who could imagine that these lines were written in the same age as those which we shall place beside them by a contemporary:—

"Hunger in hast tho' hint Wastour by the maw.

And wrong him so by the wombe that both his eies watered.

He buffeted the Briton about the chekes

That he loked lyke a lanterne al his life after."

Take now these few lines from John Barbour of the same period:—

"Ah, freedom is a noble thing!

Freedom makes man to have liking;

Freedom all solace to man gives;

He lives at ease that freely lives.

A noble heart may have none ease.

Nor nought else that may it please

If freedom fail."

Now this was the work, not of an English, but Scotch poet, who wrote in English.