Century Magazine/Volume 47/Issue 6/Jean Francois Millet's Life at Barbizon

hile studying with my brother François in his studio at Barbizon, I became familiar with painting as well as with drawing and modeling. We worked in the studio from eight in the morning till six in the evening, the only interruption being for dinner. At six o'clock in the evening we were called to supper.

His plan for me was to draw and model alternately. I had clay at my disposal, and when fatigued with the crayon I took the clay. François made me understand that the study of form is accomplished quite as well with crayon as with clay or any other material. With crayon one makes a semblance of the form by light and shade; with clay is made a reality, a true relief. The end is the same — the study of form. It is the means only which differ.

After supper François often went to take a walk on the plain or in the forest. He was fond of watching the beautiful evening effects which are produced on the plain, and although he greatly admired the forest, his preference was for the plain. There he found himself constantly en rapport with the subjects which he treated. Whether he saw fields of wheat or of clover; a woman leading her cows by a rope to pasture them in the fields; a herd of cows belonging to a large farm; a shepherd keeping his sheep with the aid of his dogs, or putting himself at the head of the flock, and the dogs keeping the procession in order, watching meanwhile to see that none remained behind or went astray from the others — all these subjects fascinated him, and kept him constantly in an attitude of observation, of which he never tired. Usually I accompanied him in his rambles.

When it was harvest-time, he would often lead the way to the places where he hoped to see the harvesters at work. When we were at a little distance from them, he would stop. "See," he would say: "all their movements count. There is nothing done uselessly. Notice, too, how well the light strikes them, and absorbs all the little details, till there remain only the stronger accents of shade which define here and there the luminous masses. The light of the plain is entirely different from that of the studio, where it enters only by a window. It is something of which a good many painters who never go out of Paris have no idea."

It sometimes happened that these harvesters would notice that we were observing them, and some of the band would say to the others: "See these Parisians who are looking at us. I should like to see them do our work. It is another thing to hold pencils, hey?"

François once said to them, "Ah, what you do is very difficult, is it not?

"If you wish to try it, you will find out," replied one. "Here, take my scythe."

This did not disturb François. He took the scythe, and began to cut the wheat with an ease and skill superior to theirs. They did not watch him long before they exclaimed: "Ah, monsieur, it is not the first time you have done this work! You do it better than we."

Continuing our walk, we came upon other objects of artistic interest. These were people binding the wheat into sheaves, and others loading the carts, and transporting the sheaves to the place where they were piling them in huge stacks. François watched this with great eagerness, saying to me: "See the grand movements of the men who lift the sheaves on their pitchforks, to give them to those who are on the stacks. It is astonishing, toward the approach of night, how grand everything on the plain appears, especially when we see figures thrown out against the sky. Then they look like giants."

As we went on, the sun began to descend below the horizon, and the whole extent of the plain was plunged into that vague light which follows the setting sun, and all became mysterious.

We heard sounds where we saw nothing; at a little distance we could see unaccountable forms moving in the darkness. All this profoundly impressed François, and he drew my attention to these mysterious evening effects that I might share his sensations. Then we turned about, and, once at home, François employed his time in reading. Sometimes he would read till eleven o'clock or even later. He was not an early riser. Generally it was eight or half-past eight before he breakfasted. Immediately after, he went to his easel, and worked until called to dinner.

All his pictures or drawings were made at the studio. His imagination answered to all his needs. Sometimes he would go out for an instant to observe certain effects, either of the clouds, or of light on some object in regard to which he felt the necessity of informing himself. Returning to the studio, he would execute from memory what he had learned and appropriated from nature.

He was often in the habit of looking at nature with a little black glass which he carried with him. In this way he obtained many valuable hints, for the black glass represents objects in a gamut, or scale, a little darker than they naturally are, and this is what one is obliged to do in painting, because, with the colors at one's disposal, actual light cannot be rendered exactly as it is in nature. The artist can produce an equivalent, but only in a darker scale, and, in accomplishing this, the black glass gives him very excellent assistance.

Our little excursions were not always directed toward the plain. We often went into the forest, our house being only five minutes' walk from the entrance-gate. This enabled us, in a very short time, to reach the localities of greatest interest.

This grand old forest of Fontainebleau is everywhere very beautiful, and, far from being monotonous in character and simply a forest of trees, it has a great variety of other natural beauties. Certain parts contain rocky hills, enriched here and there by thick heath growing on a sandy soil. In places one sees great heaps of rocks of sandstone formation piled one above the other on the slope of the hills, as if large masses of water formerly had rushed through all this country, loosening the immense rocks, and heaping them one upon the other. One peculiarity of these rocks is that many of them are formed like great living monsters. When we went into the forest toward nightfall François was always deeply moved. It seemed to him as though we were amid a crowd of antediluvian monsters, and he enjoyed pointing out to me the semblance to living forms of these mysterious shapes.

When we went in another direction, as in that of the Bas Bréau, we found an entirely different aspect. Here stood oaks of gigantic dimensions, showing the characteristics of great antiquity; some of them having trunks so hollowed by age that we could easily enter them. Some of the branches of others were dead and broken, and had become closely interlaced with creeping vines, thus forming a thicket which was nearly impenetrable. We were able to go through these thickets only by little paths which had been opened by the cows, as they were led day by day to pasture.

Lately, the Department of the Forests has opened roads through all these thick woods, to enable carriages to pass into regions heretofore unexplored, and names have been given to certain trees and rocks which serve as guides to the explorers of the forest.

Here one finds a tree called "La Reine Blanche," there is the "Charlemagne"; here the "Rousseau Rock," there the "Millet Rock," etc.

While we loitered in this wilderness, so fascinated with its weird beauty that we could scarcely leave it, we sometimes perceived in certain gaps through the trees the beautiful red tints of the setting sun, and François would say: "How suggestive that is of ideas for beautiful cathedral windows! And notice how these great trunks form columns, such as cathedrals have to sustain their domes. Evidently the ancients were struck by the aspects of forests, and many of their architectural inventions have thus been suggested."

A little later it would become very dark, and this was the hour when the deer began to venture out of their lairs. Sometimes, as we arrived at the turning of a thicket, a stag, surprised, sprang from his covert, and like a flash darted through the bushes, making their branches crack.

François always went home full of these impressions, and during the evening the memory of what we had seen would suggest to him some composition for a picture. Taking his pencil, on the first piece of paper that came to his hand he would sketch an idea, then seek to find the clearest way of presenting it, that it might be intelligible.

If any one came to pass the evening with him, it was usually another artist, or some one fond of talking about art. Long conversations, sometimes controversies, would then ensue.

When he met those who were congenial, and who sympathized with his ideas, François liked much to express his thoughts on art; but he seldom met any one with whom he could talk with an open heart—that is to say, by whom he felt himself sufficiently understood to dare tell all that he felt. In order the more clearly to express his thought, he had the habit, while talking on art, of using his pencil. On any bit of paper he would make an offhand sketch, showing how he understood the subject under discussion. By the end of the evening he would have made several sketches, to which, however, he attached no importance whatever. But they often showed a very original composition, and certain persons did not scruple to carry them away as souvenirs. This was observed, and later it was not easy to secure these sketches. During the long evenings of winter François was accustomed to read a great deal, often hours at a time. Sometimes he would read aloud. This instructed the children, and interested every one. His reading was very enjoyable, for he enunciated with distinctness, and with an intonation very easily caught by the ear. Although he stammered in conversation, his reading was quite natural, and never fatiguing to the listener. For a while he was obliged to abstain from reading in the evening. It was too fatiguing for his eyes, the service of which was demanded first of all by his work.

It was at Barbizon that François first met Théodore Rousseau, and they became intimate friends, exchanging frequent visits both at their studios and at their homes.

When Rousseau desired to take a walk, it was generally in the afternoon. He would come to the studio, and after having asked to see what François was doing, freely giving his opinion and his own ideas, would say:

"Well, Millet, you have worked enough for to-day; what do you say to taking a walk?"

The invitation was usually accepted. I had the honor of being included, and we would set out, usually in the direction of the forest.

"Ah!" Rousseau would exclaim when he found himself facing an old oak-tree, "see, Millet, what a grand, beautiful character this old oak has, and how well placed is the rock behind it! How well all that is arranged!"

From the height called Point-de-vue du Champ de Chailly we could see an immense panorama. On one side the view commanded the whole of that part of the forest called Bas Bréau. The foliage of the tree-tops was so abundant that it seemed to afford a solid surface, on which one could walk. On the other side was seen the plain of Chailly in immense extent, and with all its varied colors.

"See, Rousseau, how grand, how immense! See how the wind makes those fields of wheat undulate like the waves of the sea!"

Rousseau and Millet were very unlike, as one may infer from their work. Rousseau was essentially a landscape-painter, and it was in the woods that he found his favorite themes. The splendor of the setting sun, or a sheltered nook in the woods, were subjects he was fond of painting. Beautiful effects like these enraptured him, and naturally he sought to reproduce them. Millet, like Rousseau, was an admirer of the grandeur and richness of nature, but he was more deeply moved by another sentiment. In his mind it was man who played the principal part, and to his eyes the landscape was the stage on which the drama of humanity was represented. The continued labor which the life of man demands, his sufferings, his pains as well as his joys, his pleasures, his weariness, his rest, his peace - these were the conditions that appealed most strongly to François's imagination, and it was these which he felt himself driven to paint.

Because he chose his subjects among the workers, and showed them in their natural ways and work, political motives have sometimes been attributed to him. It has been said that he wished to show the miseries of the poor and to excite hatred toward the rich. For this reason the government authorities for a long time suspected him, and set him aside. But I can attest that such an idea never entered his head, and that politics never once suggested to him the subject of a picture or its composition. He did not even read the political newspapers, and knew nothing of the intriguing movements of the day, which every one else was discussing.

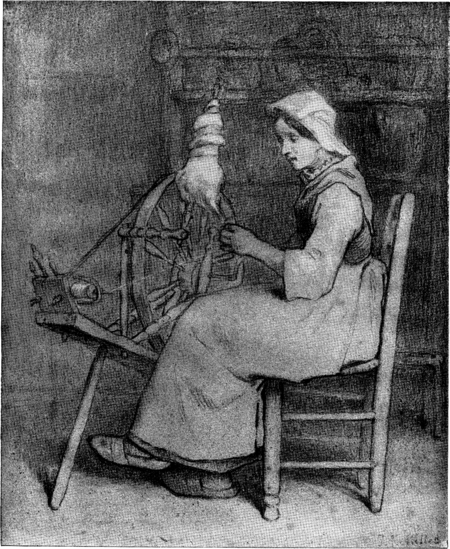

He chose the subjects of his pictures from among the familiar objects of the life in which he had been brought up, and from the work that he himself had performed; not that he wished to delineate misery, but that he sympathized with the laborious peasant life. To him it seemed the most natural condition of man, and he knew by experience that the workers of the fields do not continually grumble at their occupation; that even in many instances they enjoy it, and know how to mingle amusements with their labor. His subjects always impress one with his great love for humanity, and are not presented to excite pity on the part of the beholder. If he represents a mother showing her daughter how to sew or knit, it is always with the affection and tenderness of a mother. Or he represents a new-born lamb, which the shepherdess carries in her apron, the legs of the newly born being still too weak to walk to the sheepfold. The ewe follows her lamb, never taking her eyes from it, and has the anxious air of a mother trembling with love and tenderness for the safety of her little one. Thus he shows us the sentiment of love as it exists in nature, even among the animals.

He admired order and care in the mother of a family. He has never painted a peasant with clothes torn. He sometimes painted one with patched clothes; but surely this spoke of order in the home. He had a horror of people who went with clothes torn and unsewed, showing the want of neatness and care.

His peasant is always honest and respectable in his rustic but orderly ways, and never has a wicked or trivial air. He never made a portrait of an individual peasant. He tried to paint a type which would characterize the man of the fields.

I have often heard him criticized for invariably choosing plain people as the subjects of his pictures, when he could just as well have selected pretty faces, and thus have given his works a better chance of selling. From a commercial point of view such criticisms, perhaps, were correct, but he chose above all to make a work of art. He felt that only by giving to his figures the expression and character which belonged to their condition could he obey the laws of beauty in art; for he knew that a work of art is beautiful only when it is homogeneous. This is why François was so long unappreciated by the public, and why many, even now, do not understand him.

During the summer Rousseau lived at Barbizon, but when winter came he went back to Paris, to pass the gloomy season, and to escape the solitude to which one was forcibly condemned in spending the winter at Barbizon. Rousseau was brought up in the city, and had been accustomed from childhood to enjoy the amusements in which Paris abounds during the winter. For this reason he dreaded an isolation of four or five months' duration in that lonely village. François did not thus dread the approach of winter, for he was familiarized at a tender age with all its severity; yet when it was said that Rousseau was about to leave for Paris, it created a sensation. We felt that it would again be necessary to find resources in ourselves, and that we should now be deprived of all those agreeable reunions to which Rousseau had accustomed us; for he was very hospitable, calling about him every summer a number of friends who came to pass that season in the country, and accommodating as many as his house would hold. There we met every year M. Diaz and his family, and many others who came to enjoy themselves in the country.

During this period, the afternoon of every Sunday was devoted to pleasant walks in which we all joined; in the evening, on returning to the village, we were generally invited to spend a few hours at Rousseau's. These were simple, and at the same time distinguished, soirées where gaiety and good humor always had their place. They were also of the deepest interest to those who could enjoy artistic and intellectual conversations. At times some of the guests would give us excellent music. All felt at ease at Rousseau's home, he was so affable and kind to every one. One could not be near him and not grow fond of him. After his departure we found it indeed very lonely, and Barbizon then resumed its true rustic character. No more city people, no more artists; we saw henceforth only peasants. But François did not wholly regret this isolation of several months.

On the plain, which sometimes was covered with snow, — and even before the snow fell, when the trees began to lose their leaves, and especially after the first frost, which hastened their fall, — there were sad and gloomy days. At such times we used to make excursions through the forest roads, and watch the continual rain of leaves, which an occasional stormy breeze would convert into an avalanche, thus deepening the impression of profound desolation which we experienced. Then would come an unavoidable sense of sadness, which we felt and confessed to each other, as we continued our course. I once said to François, "It would be very pleasant to be able to pass the winter in a warmer climate, where one could continue to enjoy the verdure and the flowers." "I do not think so," he replied. "I should not like to be deprived of the impressions which winter gives me, nor would I care to live in a country that has no winter."

The winter days were too short for much work, and especially for François, who never painted by the evening light. When night came, he would quit the studio and go home. The distance was not very great, the house being separated from the studio only by a small garden about twenty-five or thirty meters in length (ninety feet). As he entered the house his children sprang forward to meet him. He would then sit down by the fire, and, taking them on his knee, frolic with them, singing comic songs, and telling fantastic stories. Sometimes he would imitate the gendarme who laughs or the gendarme who cries. He greatly enjoyed these childish amusements, and entered into them with as much zest as the children themselves.

He was fond of staying at home, and rarely made visits to any one excepting Rousseau when the latter was at Barbizon. One trouble — headache — followed him throughout his life, causing him many interruptions and much suffering. The pain was often so severe as to forbid working at least one or two days of each week. It was painful to watch his struggles against this frightful headache at a moment when he was actually obliged to finish his work. He would try to resist the evil, and forced himself to continue in order to complete a painting; for the end of the month approached, and he knew that certain bills would surely be presented, and it was absolutely necessary to pay them.

Notwithstanding this, he was often obliged to yield to the illness and to go to bed, to allow the most acute pain and the crisis to pass, and it was only on the next day, or the day after, that he could gather up his strength and resume his work. But not many days elapsed before pain returned anew, and thus the difficulty went on. His whole life was disturbed, and his work interrupted, by these headaches, which never permanently left him. During his later years the pain became less acute, but gave place to a dull, heavy feeling which allowed him very little time for work. Had he not been obliged to succumb to this cruel affliction, he would have been able to produce at least double the work that he has done. "Ah," he sometimes said to me, "if I had never quitted the open-air life of the fields, and its work, I should not have had to suffer all these terrible headaches!"

Besides depriving him of so much time, and causing such suffering, destroying his constitution, and being a detriment to him in every way, this trouble also cost him large sums of money; for several physicians successively exhausted all their science on him, and made him take frightful quantities of medicine, which did not cure him, yet were very expensive. Strange to say, they all forbade him to drink coffee, and coffee was the only thing that gave him any relief! He would return to it after trying everything that was prescribed. Very strong black coffee, free from adulteration, was a necessity to him.

He never could get such coffee except at home or at the houses of his friends. If taken ill when in Paris, he would try to get a cup of coffee at those places which made a specialty of it; but he never could find a place where it was pure. There was always chicory or something else mixed with it, and it would not produce the desired effect. Then he had to go about suffering from headache, and it often happened that he was obliged to return to his quarters and to go to bed till the next day. This harassed him much, for when he went to Paris it was always on business at the end of the month, and he knew that he must return in time to face the notes due on the first. Under such circumstances, when I was settled in Paris he often had recourse to me.

Below I give a few letters received from him on the subject. I have in my possession many others bearing on the same:

- My dear Pierre: As usual I am detained here by my headache. I need you at once at Barbizon. Come immediately if it is possible.

- François.

- Sunday morning.

- My dear Pierre: A severe and entirely unusual sickness has come upon me. In addition to a painful headache, I have sore throat and a high fever. It was necessary that I should be bled, so that, although I am again on my feet, I have been terribly shaken.

- All this has forbidden work, and prevents my going to Paris for my fu du mois [monthly payment]. I have not the strength to do it. Carefully observe, then, what I ask of you for me: Go to Rousseau's on Tuesday morning, and there you will find a sum of money, four hundred and fifty francs, I think. Bring it to me the same day. Go to Rousseau's before noon, in order to be here at dinner-time. If you cannot do this, tell me quickly, so that I can devise some other means to get this money, for Wednesday is the end of the month. You clearly understand how important it is that you should be here Tuesday evening with the four hundred and fifty francs which you will find at Rousseau's. You may say to him that I did not have the strength to go to Paris. I shall try to be there in the early part of next month, and shall doubtless set out on Monday of Easter week, for it is absolutely necessary that I should go then.

- Good-by, and good health to you. Except myself every one is all right here. Your brother,

- François.

- Monday evening.

- My dear Pierre: It is necessary that you should come to Barbizon without fail to-morrow evening.

- You know that the train leaves at five o'clock and something.

- Go to Rousseau's to-morrow afternoon at three o'clock, in order that I may intrust you with what you will have to bring. Your brother,

- François Millet.

- I count on you, for it is absolutely necessary that I remain here for important business.

Every time he went to Paris his headquarters were at Rousseau's. When he returned home to Barbizon he was always very much fatigued, and a day of rest was necessary before he could resume his work.

Thus his life passed, divided almost equally between work and suffering. When he was well, he seemed to be proof against everything. He was built like a Hercules, and was sometimes glorious in his strength. When free from his malady, he was a very pleasant companion, being fond of gaiety and wit, and provided he found himself with people who sympathized with his tastes, and quickly took the sense of his bons mots, he was often brilliant. One would never have supposed, on seeing him thus joyous in company, that perhaps the next day he would be overcome by sickness, unable to stir, or to raise his head from the pillow.

Notes

[edit]- ↑ See "The Story of Millet's Early Life," by his brother, in The Century for January, 1893.