Character of Renaissance Architecture/Chapter 4

CHAPTER IV

THE DOME OF ST. PETER'S

When in the year 1503 Pope Julius II came to the papal chair, the architect Bramante had recently settled in Rome. Born in Urbino, he had spent his early manhood in the North of Italy, where he had come under the influence of the Florentine architect Alberti at Mantua, and of the early Renaissance masters at Milan and elsewhere. Under these influences he had acquired a style that was peculiar to the North at that time. But since coming to Rome he had begun to form a new manner under the more direct influence of the Roman antique,[1] and he soon developed a style in which the ancient Roman forms were reproduced with stricter conformity to the ancient usage, and with smaller admixture of mediæval features than had before prevailed.

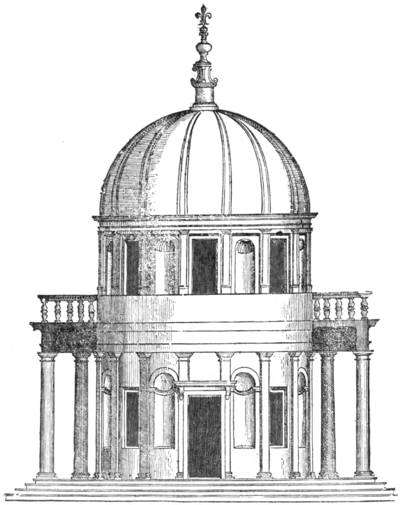

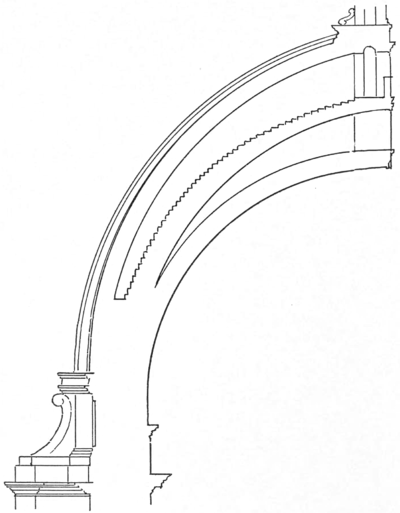

An early work in Rome in which he exhibits this more rigorous classic tendency is the small building known as the Tempietto in the cloister of San Pietro in Montorio. It consists of a circular cella with shallow pilasters, surrounded by a colonnade of the Roman Doric order, and surmounted by a hemispherical dome on a high drum. It is thus in form like a Roman temple of Vesta with its dome raised out of the abutting drum and set upon its top without abutment. A glance at Figures 21 and 22, a part section and part elevation of the temple of Vesta at Tivoli, and an elevation of the Tempietto, respectively,[2] will show how great a change Bramante made in the adjustment of the vault to the supporting drum, while it will show also the essential likeness in other points between the two monuments. In Figure 21 it will be seen that the vault is well abutted by the roof of the portico, and by stepped rings of masonry over the haunch, while in Figure 22 the drum is raised high above the encircling portico, and the vault is sprung from its top, and has no abutting rings. The architect appears to have realized that such a scheme would be unsafe on a large scale, for in the one which he prepared for the dome of St. Peter's he took care, as we shall see, to provide strong abutment.

Fig. 21.—Temple of Vesta, Tivoli, from Serlio.

The Tempietto is but a modified copy of an ancient model, and in no true sense an original design. The changes wrought by the copyist are not of a creative kind consistent with true principles of building. The pilasters, and the balustrade with which the order of the portico is crowned, are superfluous, and the work as a whole shows little of Bramante's real ability as an architect. Such merit as it has is primarily due to the ancient model which he would have done better to have reproduced more exactly.

Fig. 22.—San Pietro in Montorio, from Serlio.

But Bramante manifested his real powers in his project for the great church of St. Peter, his capital work, which, however, was never carried to completion. It is well known how Pope Julius II had conceived the idea of erecting a vast tomb for himself, and had employed Michael Angelo to prepare the design. We are told by Vasari[3] that the project submitted by this great artist so pleased the Pope that he determined to rebuild the church of St. Peter in order to make it more worthy to enshrine so magnificent a monument. Under Pope Nicholas V, half a century before, the grand old basilica, that had stood since the time of Constantine, had been partially demolished, and a new edifice on a larger scale begun by the Florentine architect, Rossellino. This work had not progressed very far when it was suspended on the death of this Pope, and operations had not been resumed until now, when Pope Julius resolved to demolish Rossellino's beginning along with what remained of the old structure, and to make a fresh start with a still grander scheme, which was prepared by Bramante, who began the new work in the year 1506.

There is much uncertainty as to the exact nature of Bramante's design for the building as a whole. No authentic drawings embodying the definitive project are known to exist, and in the monument itself Bramante did not go far enough to show his whole intention. Even what he actually did cannot be wholly made out with clearness, because so many other hands were employed after his death. The exact form of his plan is uncertain, though there appears little question that it was to be in the form of the Greek cross with towers set in the external angles, and it is certain that a vast dome was to rise over the crossing.[4] The work, though considerably advanced, was not nearly completed when, in the year 15 14, the master died. He appears to have built the great piers for the support of the dome, with their connecting arches and pendentives, but not to have begun the dome itself.

The scheme was to be a colossal one, and the dome was to be its main feature. We may presume that Bramante naturally shared the universal feeling of admiration for Brunelleschi's

Fig. 23.—Bramante's dome for St. Peter's, from Serlio.

dome, and that he wished to rival its imposing character. But his ardent and intelligent study of the monuments of Roman antiquity had given him a better appreciation of their superior structural merits, and in his project for the great dome he had sought to adhere more closely than Brunelleschi had done to the ancient principles and ancient forms.

In seeking guidance from the antique two monuments in particular appear to have appealed to him as offering appropriate suggestions, the Pantheon and the Basilica of Maxentius, then called the Temple of Peace. The first of these monuments gave the model for a mighty hemispherical vault securely suspended over a vast area, while the second offered an example of a stupendous system of piers and arches. In maturing his great scheme with these models before him, he conceived the idea of uniting their respective sublimities, and is said to have boasted that he would set the Pantheon upon the arches of the Temple of Peace. While it is probable that the majestic elevation of the dome of Florence haunted his imagination, and led him to feel that he must lift his dome high, he wished, at the same time, to give the design a more classic character, and a sounder structural form. In striving to accomplish this double purpose Bramante produced a scheme for an elevated dome of almost thoroughly Roman character, and at the same time of imposing external effect. The architect Serlio gives an illustration[5] (Fig. 23) of this project which is highly instructive.[6] A comparison of it with the scheme of the Pantheon shows a close likeness in essential forms and adjustments. The points of difference are mainly such as Bramante's desire to make his dome externally conspicuous would require. In the Pantheon (Fig. 24) the dome springs from within the massive drum at a level far below the external cornice, so that the wall above the springing forms a solid and powerful abutment, reaching almost to the haunch of the vault. Above this a stepped mass of masonry, diminishing in thickness as it rises, is carried well over the haunch, effectively overcoming any tendency to yield to the force of thrust. A Corinthian order, surmounted by an attic, is carried around the wall of the interior,[7] while the wall on the outside is plain.

Fig. 24.—The Pantheon.

In Bramante's project every essential feature of this ancient monument is reproduced, but with modifications which give a different aspect to the design as a whole, but do not constitute any such radical departure from the principles embodied in the Pantheon as those wrought by Brunelleschi in adapting the scheme of the Baptistery to that of the dome of the cathedral of Florence. In order to secure greater elevation for external effect, the architect has raised the springing level of the dome considerably, though he has still kept it below the top of the drum. The drum itself is of great thickness, and forms a strong continuous abutment at the springing, and the haunch of the vault is loaded with steps of masonry as in the Pantheon, though not quite so heavily. The lower half of the drum is a solid wall resting on the pendentives, while the upper part, which is less than half as thick (Fig. 25), is pierced with eight wide openings, and its inner and outer faces are each adorned with an order of pilasters alternating with free-standing columns in the intervals. The upper wall stands on the inner circumference of the massive lower ring, while an encircling order of Corinthian columns is ranged on its outer circumference, and gives an effect of lightness and elegance to the exterior, which, together with the lantern at the crown of the dome, goes far to disguise the real likeness of the whole to the Pantheon scheme.

Fig. 25.—Plan of Bramante's dome, from Serlio.

In these changes and additions Bramante was governed by a clear understanding of the exigencies of his project. He was obliged to raise the internal order from the place on the ground level which it occupies in the Pantheon, to the upper part of the drum, in order to provide a solid foundation resting on the pendentives; and this compelled him to eliminate the attic story of the Pantheon scheme. The most radical change was that of substituting the open colonnade for the solid wall on the outside of the drum. It is doubtful, I think, whether the drum thus lightened would have had enough strength to withstand the enormous thrusts of such a dome.

Like the dome of the Pantheon, Bramante's dome was to be hemispherical and to have an opening at its crown. Over this he was to set the lantern which in outline recalls that of Brunelleschi, though it is of lower proportions, in keeping with the less elevated form of his dome, and has a small hemispherical dome instead of a conical roof. The shape of the lantern accords well with the composition as a whole, and contributes much to the aspiring expression which was now demanded, without wholly contradicting the classical spirit that the architect was striving to maintain.

The structural merit of this scheme lies in what it has derived from the forms and adjustments of the Pantheon. Its weakness consists in the increased elevation, lifting the dome away from its abutment to such an extent that it may be questioned whether it could have been made safe without chains. The thrusts of a hemispherical dome are vastly more powerful than those of a vault of pointed outline, like the dome of Florence, but if properly abutted, as in the Pantheon,[8] it is perfectly safe, and makes a better ceiling than a pointed vault. In reducing the efficiency of his abutment by raising the springing of the dome so high, the architect ought to have diminished the force of its thrust in a corresponding degree by giving it a pointed form. This would have made it more safe, but it would have been inconsistent with the classic Roman models to which he was striving to conform.

As for Bramante's intended architectural treatment of the rest of the building we have, as before remarked, no precise information. It appears, however, most probable that he meant to cover the arms of the cross with barrel vaulting on massive square piers and arches, with a single order of pilasters such as Alberti had used in St. Andrea at Mantua, and such as Michael Angelo actually employed, though in a way peculiar to himself, and probably unlike that in which Bramante would have done it. For Bramante would, I think, have followed Alberti's example in raising the order on pedestals—the great scale of St. Peter's especially calling for such treatment. Bramante would have realized that a single order large enough to rest directly on the pavement and allow the entablature to pass over the crowns of the arches of the great arcades, would dwarf the apparent scale of the whole interior, as Michael Angelo's order actually does. But whatever his intention was as to these details, Bramante died before they could be carried out, and we are left in the dark as to what the church as a whole would have been had he lived to complete it.

To the work of his numerous successors prior to the appointment of Michael Angelo, we need give no attention because their labours did not materially affect the final result. Their work was largely on paper only, and the building as it now exists is substantially Michael Angelo's design, based on that of Bramante, but with extensive, and damaging, additions by subsequent architects.

Michael Angelo at the time of his appointment as architect, in the year 1546, was seventy-two years of age. He professed great respect for the original scheme of Bramante, yet he radically changed the form and adjustment of its main feature, the dome. In conformity with Bramante's project, he made the drum massive at the base and thinner above, but in place of Bramante's external colonnade surmounted by a solid ring of masonry, forming a continuous abutment at the springing of the vault, he substituted a series of sixteen isolated buttresses, and raised the dome so high above them that they do not meet its thrusts at all. The drum is carried up above the buttresses so as to form an attic over the order with which the buttresses are ornamented, and from the top of this attic the dome is sprung. The stepped circles of abutting masonry at the haunch are omitted, and instead of one solid vault shell, such as Bramante intended, Michael Angelo's project provided for a variation of

Fig. 26.—The model.

Brunelleschi's double vault, and was to include (as the model, Fig. 26, shows) three separate shells.[9] The inner shell was to be hemispherical (Michael Angelo thus showing that he appreciated the superior character of the dome of the Pantheon and that of Bramante's scheme to the dome of Brunelleschi as to internal effect), while the other two were to be pointed, with diverging surfaces. Following Brunelleschi, he introduced a system of enormous ribs rising over the buttresses of the drum, and converging on the opening at the crown of the vault. These ribs unite the outermost two shells, extending through the thickness of both, and support the lantern.

Of this hazardous scheme only the drum was completed when Michael Angelo died. But the existing dome, which was carried out by his immediate successors, is substantially his design, though the innermost shell of the model was omitted in execution, and the vault was thus made double instead of three-fold (Fig. 30). This dome does not, however, divide into two shells from near the springing, but is carried up in one solid mass almost to the level of the haunch. Michael Angelo may have thought that this would strengthen it, but the solid part has not a form capable of much resistance to thrust, and the isolated buttresses are located so far below the springing that they contribute practically nothing to the strength of the system, as already remarked, and as we shall presently see.

Although this great dome has been almost universally lauded, it is entirely indefensible from the point of view of sound principles of construction. The work shows that Michael Angelo was not imbued, as Bramante had been, with a sense of the essential conditions of stability in dome building as exemplified in the works of Roman antiquity. He had conceived an ardent admiration for the dome of Florence, and in emulation of it he changed the external outline from the hemispherical to the pointed form, and, lifting it out of the buttressing drum, set it on the top.[10]

This vast dome is an imposing object, but it is nevertheless a monument of structural error. Not only does its form and construction render it much less secure than Brunelleschi's dome, but its supporting drum is entirely unsuited to its function, save as to its strength to bear the mere crushing weight of the vault. In replacing the continuous colonnade, with its abutting load, of Bramante's drum by the isolated buttresses, Michael Angelo ignored the true principle of resistance to the continuous thrusts of a dome. It has been thought that the rib system justifies this, that the ribs gather the thrusts upon the buttresses and give the dome a somewhat Gothic character. But this cannot be so. It is impossible for a dome to have any Gothic character. In addition to what has been already said (p. 20) on this point, it may be further remarked that, so long as the surfaces between the ribs remain straight on plan, as in the dome of Florence, or are segments of a hemisphere, or of a dome of pointed form on a circular base, like the dome of St. Peter's, no ribs can be made to act in a Gothic way. A circular vault on Gothic principles would necessarily be a celled vault, more or

Fig. 27.

less like the small vault of the Pazzi already described (p. 27). In such a vault there would have to be an arch (in a true Gothic vault a much stilted arch) in the circumference of the drum over the space between each pair of ribs. The crowns of these arches would reach to a considerable height, in a developed Gothic vault to nearly or quite the height of the crown of the vault itself. The triangular spaces enclosed by these arches and converging ribs would then be vaulted over by slightly arched courses of masonry running lengthwise of the triangle, or from the arches to the ribs, and approximately parallel with the crown of the cell (A, Fig. 27). Thus in place of an unbroken hemispherical or oval vault, we should have one consisting of deep cells. The drum would have to rise far above the springing, and the haunches would need to be loaded with a solid filling of masonry. The vault would thus be completely hidden from view on the outside. Nothing short of this would produce a circular vault on Gothic principles, or one in which the ribs could act in a Gothic way.[11] The nearest approach to such a form, in a vault that may with any propriety be called a dome, occurs over the crossing of nave and transept in the old cathedral of Salamanca in Spain (Fig. 28).[12] But this vault has a

Fig. 28.—Interior of dome of Salamanca.

Fig. 29

The vault of Salamanca is not a Gothic vault in any sense, though its rib system and its hollowed cells conform with the earliest stage of apsidal vault development leading to Gothic.[13] It is a dome, and like the larger dome of St. Peter's, it is sprung from the top of the drum; but unlike St. Peter's dome, it is powerfully abutted by turrets and dormers built against its springing and its haunch, and it is loaded at the crown with a cone of masonry, so that from without it looks like a stumpy spire, and not like a dome.[14]

But Michael Angelo's vault has not even such remote approach to Gothic character as the small dome of Salamanca has. Its surface is unbroken by any hollowing into cells. It is a perfect circle on plan, and its ribs, which are embedded and not salient on the inside, cannot, therefore, sustain the vault in any Gothic way. This dome has, moreover, so much of a spherical shape as to give it a stronger tendency to thrust than the dome of Florence has, and the thrusts are exerted equally on all points in the circumference of the drum. The isolated buttresses are therefore illogical, and being set against the drum only, and not even reaching to the top of the drum, they are ineffectual. Thus though the dome was bound with two iron chains, one placed near the springing, and the other at about half the vertical height of the vault,[15] it began to yield apparently soon after its completion. Fissures opened in various parts of both dome and drum which at length caused such apprehensions of danger, that Pope Innocent XI called a council of the most able engineers and architects of the time[16] to examine into the extent of the damage, and ascertain whether serious danger existed. This council concluded that the cupola was in no danger of disintegration, and the Pope, in order to restore confidence in its safety, charged Carlo Fontana, the architect, to write a book on the building and prove the groundlessness of any fears of its collapse. Thus the matter appears for the time to have been dropped. But subsequently the concondition of the structure became so alarming that three eminent mathematicians, among whom was the celebrated Boscovich, were, in the year 1742, commissioned by Pope Benedict XIV to make a further examination and submit a report with recommendations for its consolidation.

The condition of the fabric at the time of this examination will be understood from Figure 30, a reproduction of the illustration subjoined to the mathematicians' report.[17] They found the structure, as the illustration shows, rent into numerous fissures, some of which were large enough to allow a man's arm to be thrust through them. In some places these cracks had been filled up with brick and cement, and new ones had opened in the filling.[18] At what time the ruptures had commenced could not be definitely ascertained, but the mathematicians express the opinion, for which they state their reasons, that they may have started very soon after the completion of the work.[19] That they were not due to any weakness in the substructure was shown by the fact that this remained apparently quite firm. Had the fractures been caused by any weakness in the piers or pendentives, the mathematicians say,[20] they would be wide at the base of the drum, whereas they were found (as shown in the illustration) to be small at the base and to increase in magnitude toward the top of the drum, and in the region of the haunch of the dome. This was thought by them to show that they were clearly due to weakness resulting from the form of the structure. The report states[21] that the weight of the lantern had caused the heads of the great ribs to sink, the dome to expand at the haunch and at the springing, and the wall of the drum to be pressed outward at the top. To consolidate the fabric they recommended that additional chains be placed at various levels, the old ones having, they thought,[22] burst asunder by the force of the thrusts; but this could not be verified because they are embedded in the masonry. They also recommended clamps of iron to hold in the buttresses.

The Marquis Poleni of Padua, a distinguished engineer of

CVPOLA DI S PIETRO

Fig. 30.—The dome with its ruptures.

safe as the general tenor of his book would lead us to believe. And the same misgivings are betrayed in what is said by the numerous other writers whose opinions are cited by him, though like himself they write for the most part with a manifest bias in favour of Michael Angelo. Thus one of these writers proposes that the outer covering of lead should be stripped off on account of its weight, and be replaced with copper, to which Poleni objects,[23] affirming that the weight is an advantage, and tends to hold the dome together. Another writer suggests that the lantern be removed in order to relieve the fabric of its weight. Another thinks that the buttresses should be heavily weighted with statues. It was also proposed that additional buttresses should be set against the attic of the drum, and carried up against the dome itself; and again it was proposed that massive abutments be built up over each of the four great piers, but to this it was objected that the additional weight of such abutments would dangerously overcharge the substructure. The most radical suggestion was that both dome and drum be demolished and rebuilt in a more pointed form. All of these suggestions were rejected, and it was finally decided to employ the additional chains proposed by Poleni as already stated.

The dome of St. Peter's (Plate III) was conceived in a grandiose spirit, which, while it drew inspiration in part from the ancient Roman source, recklessly disregarded the lessons which Roman art should teach as to principles of construction. I have said that Brunelleschi led the way in a wrong direction when he set his great dome on the top of its drum, and had resort to clamps and chains for the resistance to its thrusts that should have been given by abutment. In following his example, Michael Angelo wandered still farther from the path of true and monumental art. To make a dome on a large scale a conspicuous object, from the springing to the crown, is a thing that cannot be safely done in stone masonry. To make it stand at all, resort must be had to extraneous and hidden means of support, and even these are of uncertain efficiency for any length of time. The ancient Roman and the Byzantine builders settled, I think, for all time the proper mode of constructing domed edifices. Bramante had recognized this, and while striving to include in his design for the dome of St. Peter's as much as he could of the new character embodied in Brunelleschi's dome, he tried at the same time to keep safely within the limits of the principles that had governed the ancient practice. He gave as much elevation to his dome as he thought these principles would allow, but even this, as we have seen, was too much, and in greatly-increasing this elevation, so as to leave the dome entirely without abutment, Michael Angelo took unwarrantable risks, and lent his genius to the support of false principles.

That this has not been generally recognized is due to the fact, already remarked, that the architects and leaders of taste of the Renaissance have made too little account of structural propriety, and structural expression, as a necessary basis for architectural design.

Recent writers have ignored the condition of this monument. They do not appear to be aware of it; and although it has been fully set forth, and discussed at great length by the earlier Italian writers, few of them have found the true cause in its flagrant violation of the fundamental laws of stability. They attributed the alarming progress of disintegration, as we have seen, to accidents and circumstances of various kinds; and have sought to shift the responsibility to the shoulders of Bramante. They have affirmed that he did not take enough care to make his foundations secure. There appears to be some justice in this, though since his work was strengthened by his immediate successors[24] the ruptures in the dome cannot, according to the mathematicians, be attributed to this. The remarks of the old writers on Bramante must, I think, be taken with some allowance. Their bias against him is very marked. Thus Poleni quotes Condivi, a disciple of Michael Angelo, as saying, "Bramante being, as every one knows, given to every kind of pleasure, and a great spendthrift, not even the provision given by the Pope, however much it was, sufficed him, and seeking to expedite his work, he made the walls of bad materials, and of insufficient size and strength."[25]A great deal has been said of the beauty of St. Peter's dome. It has been held up as a model of architectural elegance by countless writers from Vasari down. But no abstract beauty, no impressiveness as a commanding feature in the general view of the ancient city that it may have, can make amends for such structural defects. Its beauty has, however, I think, been exaggerated. Its lack of visible organic connection with the substructure makes it inferior in effect to the dome of Florence, where the structural lines of the edifice, from the ground upward, give a degree of organic unity, and the buttressed half-domed apses, grouped in happy subordination about the base of the drum, prepare the eye to appreciate the majesty of the soaring cupola as it rises over them. The dome of St. Peter's has not the beauty of logical composition. Beauty in architecture may, I think, be almost defined as the artistic coordination of structural parts. As in any natural organic form, a well-designed building has a consistent internal anatomy, and its external character is a consequence and expression of this. The dome of St. Peter's violates the true principles of organic composition, and this I believe to be incompatible with the highest architectural beauty.

- ↑ Vasari, op. cit., vol. 4, p. 152, and Milizia, vol. i, p. 214.

- ↑ Figures 21 and 22 are taken from Serlio, D'Architettura, book 3, Venice, 1560, pp. 25 and 40.

- ↑ op. cit., vol. 7, p. 163.

- ↑ Serlio, the architect (a younger contemporary of Bramante), op. cit., p. 33, tells us that Bramante, at his death, left no perfect model of the whole edifice, and that several ingenious persons endeavoured to carry out the design, among whom were Raphael and Peruzzi, whose plans he reproduces. That ascribed to Raphael has a long nave, while that said to be by Peruzzi has the form of the Greek cross with round apses and a square tower in each external angle. The whole question of Bramante's scheme, and of the successive transformations to which the design for the edifice was subjected before its final completion, is fully discussed in the work of Baron H. von Geymüller, Die ursprünglichen Entwürf für Sanct Peter in Rom, Wein and Paris, 1875-1880.

- ↑ Op. cit., bk. 3, p. 37.

- ↑ Serlio does not state on what authority this illustration is based, but there appears no reason to question its correctness. Its authenticity is discussed by Baron von Geymüller (op. cit., p. 240 et seq.), who accepts it as genuine.

- ↑ The alterations that have been made at different times since the original completion of this interior are of no concern here. The arrangement was practically the same in Bramante's time as it is now.

- ↑ Some writers have supposed (cf. Middleton, Ancient Rome, Edinburgh, 1885, pp. 338-339) that the dome of the Pantheon is entirely of concrete, and without thrusts. We have no means of knowing its exact internal character, but there is reason to believe that it has some sort of an embedded skeleton of ribs and arches, with concrete filling the intervals. But if it were wholly of concrete, as Middleton affirms, it would not be safe without abutment; for, even supposing that a concrete vault may be entirely free from thrust in a state of integrity, there is always a chance of ruptures arising from unequal settlement, which might at once create powerful thrusts. However this may be, the fact is that the builders of the Pantheon took care to fortify it with enormous abutment, which would seem to show that they did not consider it free from thrust.

- ↑ Michael Angelo's model, on a large scale and finished in every detail, is preserved in an apartment of St. Peter's.

- ↑ Michael Angelo's remark, quoted by Fontana (Tempio Vaticano, vol. 2, p. 315): "Imitando l'antico del Pantheon, e la moderna di Santa Maria del Fiore, corresse i difetti dell'uno, e dell'altro," shows that he regarded as a defect the lowness of the Pantheon dome, which in point of construction is its capital merit, and that what he proposed to correct in the dome of Florence was its octagonal form, which is essential to its peculiar structural system.

- ↑ A consistent exterior for such a vault would not, of course, be an unbroken drum, though a perfectly Gothic circular vault might be thus enclosed within a drum. A consistent external form would require salient buttresses against the lines of thrust, and the intervals between these buttresses would be open, as in a Gothic apse.

- ↑ The outside of this vault is figured in my Development and Character of Gothic Architecture, 2d edition, New York and London, The Macmillan Co., 1900, p. 287.

- ↑ Cf. my Development and Character of Gothic Architecture, p. 70 et seq.

- ↑ The turrets, built upon the supporting piers of the interior, give the outside of the drum the aspect of a massive lantern.

- ↑ Cf. Poleni, Memorie Istoriche delle Gran Cupola del Tempio Vaticano, e de' Danni di eisa, e de' Ristoramenti loro (Padua, 1768), p. 29.

- ↑ Milizia, op. cit., vol. 2, p. 325.

- ↑ Parere di tre Mathematici sopra i danni che si sono trovato nella cupola di S. Pietro sul fine dell’ Anno MDCCXLII. Data per Ordine di tiostro Signore Papa Benedetto XIV, Rome, 1742.

- ↑ See Appendix.

- ↑ "Cominciato forsi poco dopo terminata la fabrica." Op. cit., p. 13.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 14.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 15.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 19.

- ↑ Op. cit., p. 399.

- ↑ The principal work of Bramante's immediate successors on the fabric itself appears to have been to strengthen the great piers, which seem to have been built too hastily, and on insecure foundations. Poleni tells that in order to strengthen these foundations, well-holes were dug under them and filled with solid masonry, and that arches were sprung between these sunken piers, consolidating the whole. Op. cit., p. 19.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 19.