Darien Exploring Expedition (1854)

HARPER'S

NEW MONTHLY MAGAZINE.

No, LVIII.—MARCH, 1855.—VOL. X.

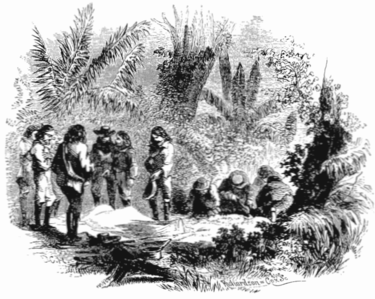

camp scene

| DARIEN EXPLORING EXPEDITION, |

UNDER COMMAND OF LIEUT. ISAAC GRIER STRAIN.

BY J. T. HEADLEY,

[Having from the first become deeply interested in the Darien Exploring Expedition, and afterward doubly so in the fate of Lieutenant Strain, I was very anxious to know its history. Subsequent acquaintance with Lieutenant Strain, ripening into a warm friendship, enabled me to gratify this desire. With that grew the wish to make the facts public. At my request, therefore. Lieutenant Strain gave to me his private report to the Secretary of the Navy, whose permission to use it was cheerfully granted, also the journals kept by both parties, together with the book of sketches made by the draughtsman. Interesting interviews with Lieutenant Maury and civil engineer Mr. Avery, have enabled me to add many details not incorporated either in the report or the journals. For any personal matters relating to Lieutenant Strain I solely am responsible, as well as for any special praise bestowed on him. I know it would be his wish that I should speak of him personally as little as possible; but I have thought it best to look only at the truth and interest of the narrative, and make every other thing subservient to these.

IT is not necessary here to speak of the importance to the whole civilized world of a ship canal across the Isthmus of Darien, nor of the different surveys that have been made.

The route of the following Expedition, beginning in Caledonia Bay and ending in Darien Harbor, had not been passed over since 1788. and was a terra incognita. In 1849, an Irish adventurer published a book, which went through several editions, in which he declared that he had "crossed and recrossed it several times and by several tracks," and that only "three or four miles of deep cutting" would be necessary for a ship canal the entire distance. Aroused by this report—which proved to be a mere fiction—Sir Charles Fox and other heavy English capitalists took up the subject, and sent out Mr. Gisborne, a civil engineer, to survey the route. He pretended to do so. and also published a book. mapping down the route, and declaring that it was only "thirty miles between tidal effects" and the "summit level one hundred and fifty feet." An English company was immediately formed with a capital of nearly $75,000,000.

Without following the progress of this scheme in England and on the Continent, it is necessary, in this connection, to state only that Mr. Gisborne's favorable report resulted in enlisting England, France, the United States, and New Granada, in exploring together the proposed route for a ship canal across the Isthmus. It will be seen in the succeeding pages that this report was also a fiction; that Mr. Gisborne never crossed the Isthmus at all—never saw across it—never advanced more than a dozen miles inland at the farthest—and, in fact, was afraid to make the attempt, and that, instead of the summit-level being 150 feet, it is at least one thousand feet. As an inevitable result, therefore, the various expeditions, relying as they did entirely on this report, with its accompanying maps, would be led into error, and in the end completely baffled. The English one, starting from the Pacific side December 23d, 1853, proceeded up the Savana, and cutting its way more than 26 miles from the place of debarkation on that river, finally became disheartened, and, with the loss of four men slain by the Indians, returned discomfited to the ships. Strain, from the Atlantic side, started nearly a month later. Three days after his departure, another expedition, composed of French and English together, under the guidance of both Dr. Cullen and Mr. Gisborne, set out from the same point, and endeavored to follow in his track. But, notwithstanding they had the men who said they had crossed and surveyed the Isthmus—the former having walked it "several times and notched the trees"—they were unable even to get out of Caledonia Valley, and after having penetrated not more than six miles in all returned. Gisborne and Cullen could not follow their own maps, not to mention the notched trees. The Granadian expedition started still later. This was a very large party, under the command of Codazzi, the principal engineer of New Granada. How far it penetrated is not known, but straggling over the space of a mile it was completely broken up, and returned, after having lost several men. It is with feelings of national pride I state that the American expedition, under Strain, alone accomplished the passage, though under an accumulation of suffering rarely recorded in the annals of man.

On the morning of the 17th of January, 1854, the Cyane, Captain Hollins, with Lieutenant Strain and his party on board, entered Caledonia Bay, where they were immediately visited by a number of Darien Indians, some of whom spoke broken English and Spanish, which they had acquired in their intercourse with the traders on the coast. They came on board fearlessly, were very intelligent and observant, and, though much below the ordinary stature, were strongly built and athletic.

On the 18th a council was held which lasted about eighteen hours, and finally terminated favorably. For a long time the chiefs resisted Hollins's demand for permission for Strain's party to traverse the Isthmus, and opposed the project of a canal most pertinaciously, insisting that if God had wished one made, he would have given greater facilities (an opinion in which Strain fully coincided before he got across), and that they ought not to be disturbed in the quiet possession of the land which the Almighty had given them. Strain replied that God had created them naked, but they had chosen to clothe themselves, which was as much an infraction of his laws as it possibly could be to construct a canal. To this special pleading they could not reply, and finally, believing that Captain Hollins would send a party through their country with or without their permission, gave their consent, remarking that it appeared to be the will of God that they should cross; and after stipulating only that they should not disturb their women, and respect their property, cemented the treaty by a hearty supper, during which they indulged freely but not immoderately in strong liquors.

Relying on Mr. Gisborne's book, the party took only ten days' provision. Each member of it, with the exception of Mr. Kettlewell, the draughtsman, had either a carbine or a musket, with forty rounds of ball cartridges; while eight of the officers and engineers had, in addition, a five-barreled Colt's revolver, with fifty rounds of ammunition to each pistol. The arms and provisions, in addition to the blankets and minor articles, brought the average weight borne by each individual to about fifty pounds, which was quite as much as they could carry through a pathless wilderness, and in a tropical climate.

The naval officers who were detailed for the expedition were—Passed midshipmen, Charles Latimer and William T. Truxton, and 1st assistant-engineer, John Minor Maury, whom Strain appointed assistant-astronomer and secretary, having obtained sufficient knowledge within the last ten years of his high capacity in each department. Mr. Latimer, however, being taken ill, never started. Mr. Truxton was appointed acting master and executive officer.

Midshipman H. M. Garland, of the Cyane, accompanied the party as a volunteer. The assistant-engineers were Messrs. A. T. Boggs, S. H. Kettlewell, J. Sterret Hollins, and George U. Mayo. Dr. J, C. Bird, of Wilmington, Delaware, was the surgeon. In addition to these were three others, volunteers.

Messrs. Castilla and Polanco, commissioners appointed by the New Granadian government, also determined to accompany the party, which numbered, all told, twenty-seven men. Having safely landed his little band, Strain drew them up, read his instructions to them, and then took up the line of march for a small fishing village at the mouth of the Caledonia river, where good water could be obtained.

As the huts were abandoned by the Indians, they took possession of them for the night, and, having stationed four armed men as sentinels, stretched themselves on the floor. But the heavy booming of the surf, as it fell in regular and tremendous shocks at their feet, made it like sleeping amidst the incessant crash of artillery. The billows, as they broke on the beach, swept on—through the houses, over the sand spit, and into the river beyond.

THE COUNCIL.

On the morning of the 20th, the party was early afoot—and while waiting for some provisions and other articles for which they had sent to the Cyane, Strain endeavored to obtain a view of the valley above by opening a path to the summit of a hill on the right bank of the river, near its mouth, and some knowledge of their route by sending a party to cut up the left bank of the river. Here, as he from the top of this hill swept the mountain-range with his glass, the first feeling of doubt and misgiving arose within him, for in an unbroken chain that range stretched onward till it abutted on the sea, showing nowhere the depression indicated on the maps.

This little band of explorers, as they boldly struck inland and began to traverse the intricate forests of the tropics, presented an interesting spectacle. Officers and men were all dressed alike in blue flannel shirts, with a white star in the collar, blue trowsers and belt. The only distinction between them was, the latter wore blue caps without a front-piece, while the former had Panama hats, and pistols in their belts. These caps were stuffed with tow, which afterward served an admirable purpose in kindling fires. A spy-glass strapped to Strain's shoulders distinguished the leader. The order of march was single-file—the leading men carrying a macheta (cutlass) or ax to clear the way. The others followed, each carrying a blanket, haversack, carbine, cartridge-box, and forty rounds of ammunition. It being necessary that the men should be well armed, not much additional weight could be imposed upon them. Strain, an old woodman and explorer, thoughtfully put a linen shirt under his woolen one, anticipating the want of linen with which to dress wounds. That shirt afterward did good service to his wounded, lacerated men.

Taking the bed of the Caledonia river—dragging a single canoe after them until the shallowness of the stream compelled them to abandon it—they pushed vigorously up the Pacific slope, and near sunset reached a large island in the river. Following a path, they found deserted huts similar to those they had left at the mouth of the river, and there determined to encamp. The huts had evidently been deserted in haste, for stools, gourds, and cooking utensils, were strewn over the floors. These, as well as the extinguished brands of a recent fire, were all collected together and placed under charge of a sentry. In the morning they were restored as nearly as possible to their original positions, as Strain was determined to give the Indians no pretext for a display of hostility; although he felt sufficiently strong in numbers and preparation to cope with any tribe they would probably meet on the Isthmus. The rancho was surrounded by a plantation of cocoa, which, with the exception of tortoise-shell, is the only exchangeable product of the Darien Indians. A strict watch was kept during the night, there being two seamen and two officers or engineers, armed to the teeth, at all times on guard, while the remainder of the party had their arms beside them and their cartridge-boxes buckled on. These, silent and motionless, kept anxious watch in the midst of those deserted huts, whose very abandonment seemed portentous of evil. At length the wished-for light appeared, when the shrill and protracted boatswain's call, "Heave round"—the cheering strains used to quicken the sailors as they tread round the capstan to heave the anchor to the cat-head—startled every sleeper to his feet. "Saddle up," then rang through the encampment; and soon every man had his blanket and haversack swung to their places, and, with carbine in hand, stood ready to march. At half-past six they set out; and now wading in the bed of the river, and again following paths along its banks, through plantations of cocoa, plantains, and Indian corn, they pushed on until they came to a point where a small tributary entered from the southward and westward. Here they had a good view of the Valley of the Caledonia; and Strain, taking advantage of it, carefully examined the range of the Cordillera with an excellent spy-glass, and finding only a semicircular chain, from fifteen hundred to two thousand feet in height, abutting upon the sea-coast ranges to the westward and southwestward, determined to follow the easterly, or principal branch of the river, believing that it offered the stronger probability of a gorge through to the other slope.

Soon after passing the tributary already alluded to, they followed a well-beaten path on the left bank of the river, which soon brought them to an Indian village, containing some forty or fifty houses, grouped among trees and surrounded by large plantations of cocoa and plantains, and a small quantity of sugar-cane.

An occasional glance through the interstices of the bamboo walls at the interior of these houses—which were spacious and well-constructed—showed that, though devoid of inhabitants, much of their personal property still remained. The grunting of pigs and the crowing of cocks left behind by their owners, gave the only evidence of life in this deserted village, except the steady tramp of the heavily armed and overloaded party. These familiar sounds added inconceivably to the desolation of the scene, and impressed deeply the whole band. Strain, with his cocked carbine in his hand, strode on in advance, his eye rapidly, almost fiercely, searching every suspicious-looking spot; while the men, each one with his weapon resting in the hollow of his arm, pressed swiftly after. Not till the last hut was passed did they breathe free again. As they emerged from this village, they found a path which wound down a steep bank to the river, near the opposite bank of which lay a canoe containing women's clothing, abandoned evidently in the haste of their flight. As Strain was about to descend by this path, three Indians suddenly appeared. After an interchange of friendly signs, one of them offered to point out to him, as he supposed, the path leading to the Pacific. He accordingly countermarched; but, after accompanying his guide a few hundred yards, came to the conclusion that the latter only wished to lead them from the village; for in the direction he took, toward the west and southwest, Strain, as already mentioned, could see no opening whatever in the Cordillera. He accordingly halted the party, and explained to the Indian as well as possible, that he would proceed no further in that direction, and was determined to follow up the main branch of the river. The latter made no opposition, but shrugged his shoulders; and turning down a ravine to the river, led up its bed until they had passed the village, then courteously took leave. Subsequent events convinced Strain of the good faith of this Indian, who doubtless would have led him into a path across the Cordillera, which he afterward discovered by mere accident. At ten o'clock the order to halt passed down the line; and the party, still suspicious, breakfasted in the bed of the river. A fire was kindled, some coffee and tea made, which, with pieces of pork stuck on sticks and toasted in the fire, made a comfortable meal. The repast being ended, the party started forward, keeping the bed of the stream till mid-day, when Strain ordered a halt, thoroughly convinced from its course—which inclined strongly toward the Atlantic—its rapid fall—which imparted to it almost the characteristics of a mountain torrent—and the aspect of the mountain ranges which crossed his course, towering some two or three thousand feet above the level of the sea, that this route could afford no facilities for a ship canal, and could not be that alluded to by either Mr. Gisborne or Dr. Cullen. While the main body remained halted here, Messrs. Truxton, Holcomb, and Winthrop were sent up the river to reconnoitre, and upon returning reported unanimously that the route in that direction was impracticable. Having received this report, they rapidly retraced their steps, finding, as they had done in the ascent, several canoes containing women's clothing drawn up on the beach. Their owners were invisible, having doubtless hidden themselves in the forest; but the fact of their having fled up this branch of the river to avoid the party,

SECTION OF THE ELEVATION OF THE ISTHMUS.

was additional evidence to Strain that he had taken the wrong direction. Marching rapidly past the village, which seemed to be occupied, he followed the smaller branch toward the southward and westward—the India-rubber, cotton-wood, and other tropical trees, gracefully festooned with parasitic plants, darkening the way, which was enlivened only by the laugh of the men as their companions, now and then, tumbled over a rock into the water. About sunset they encamped on the right bank of the stream. The officers and men were divided into two messes, each having its separate fire and cook. This second day's tramp had been a hard, exciting one, and the men were glad to halt. After tea, the two groups sat around their respective fires, smoking, telling stories, and singing, till the watch was set. An officer and two sentries formed, this night and for a long time afterward, the regular guard from eight in the evening until daylight. The two fires were kept brightly burning all night, shedding their steady light over the motionless party as they slept in pairs, with one blanket beneath and the other above them, under the open sky. They were a splendid set of men, and, as they lay there in order of battle, seemed well fitted for the hardships before them.

Roused up by the boatswain's whistle, the party breakfasted, and again set out, wading about a mile up the river, until they arrived at a "cañon" in which the water was so deep to place fording out of the question, while the scarped rocks on either side made the ascent to the bank above very difficult. From the outset, as the way became more and more obstructed, Wilson, who had a splendid voice, cheered on the party by making the woods ring with "Jordan is a hard road to travel." While stumbling up the rocky bed of the Caledonia, he had changed his song into "Caledonia is a hard stream to travel," in which there was far more truth than poetry. It was a relief to all, therefore, when Strain ordered a halt, and informed them that it was his intention to leave this river soon, as it was leading toward a very high range of mountains and too far to the southward. Holcomb and Winthrop were for continuing on, and the former having found an accessible point on the bank of the "cañon" to ascend, and displaying some impatience to attempt it, and as some of the party appeared anxious to follow, Strain gave permission, but at the same time recommended them to follow him a short distance below, where a more gentle ascent might be found, and one less likely to tire the heavily-laden party. They did so, and soon came to an easy slope, up which they pushed. They had not proceeded far when they unexpectedly stumbled on a well-beaten track leading over the hills to the southward and westward. This was an unlooked-for stroke of good fortune, and Strain was convinced that he had found by accident the traveled Indian route to the Pacific. He now recalled the scattered party—first by shouting, as they were near, then by the boatswain's whistle, and finally by firing his carbine. The stragglers soon closed in, but upon counting the party to see who might be missing, he found that Holcomb, Winthrop, Hollins and Bird, and Roscoe, a seaman of the Cyane, were absent. He then fired three carbines in quick succession, the previously established

THE CAÑON.

Early in the morning he sent scouts across the mountain, to see if they had not crossed higher up on the Caledonia, and reached the river valley which he was confident must exist on the other side. At half past nine they all returned, unsuccessful, but reported having found a large stream, which they believed united with that on which they then were, which afterward proved to be the fact.

Deeply solicitous as Strain was about the absent men who had been intrusted to his care, and for whom he was in a great measure responsible, he felt the obligation also not to make any delays that should endanger those still under his command nor the success of the expedition, and at ten o'clock gave the welcome order to move forward. Keeping in view this river to its junction with the Sucubti, they followed the latter in its rough and tortuous course, struggling over huge boulders and masses of stones rolled together by the torrent, and which rendered the way almost impassable. Dangerous rapids also intersected their path, skirted by precipitous banks, along and up which, heavily laden, they scrambled with great difficulty, until at last, fatigued and hungry, they encamped at five o'clock at the mouth of a small stream, having made in all not more than eight or nine miles. All day long, whenever they struck a sandy reach, they found fresh Indian tracks always in advance, but as there appeared to be only two men, and they accompanied by a dog, Strain felt no anxiety, as he knew their strategy never admits of a dog on a war-path. On the morning of the 24th, at nine, a.m., they left their bivouac and proceeded down the bed of the river, occasionally pursuing the banks when it was deep or impassable from falls or boulders. The trail of the two Indians and dog was still very distinct, and it was evident that they had slept in the immediate vicinity of the last night's camp. About eleven o'clock, while wading down the bed of the river, a smoke was seen rising through the trees, and immediately the quick order, "Close up," passed down the line. Soon after, Strain commanded a halt, and advancing alone, mounted the left bank, and found an Indian hut, apparently just abandoned, and on fire; the roof had already fallen in, while the joists and timbers were slowly burning and crackling in the still air. Two other houses on the opposite bank were also in flames. Strain immediately crossed over, and found that, as in the first, all the stools, pots, and other utensils were left a prey to the flames, but their arms and clothing had been taken away. While examining these two houses, Mr. Castilla, the New Granadian commissioner, came up the bank, and seeing a bunch of plantains hanging on a rafter, reached up to take them; but Strain stopped him, declaring that he had promised to respect private property religiously, and was determined to give the Indians no excuse whatever for assailing his party. This destruction of their property looked ominous, and could be construed in no way, except as an evidence of hostility; and Strain now began to anticipate a gathering among them, and an attack at some favorable point in advance. He therefore ordered the men to re-examine their arms carefully, and march in close order. Still leading his little band, he kept on the difficult path, expecting every instant, for hours, a shower of arrows upon his party. He, of course, would be the first victim; and he confessed afterward that he remembered the account given by a comrade in Texas, of the sensation the latter once experienced with two arrows in his body, and the remembrance made him squirm. But compact and silent they kept down the river, generally wading in its bed, and where the water was too deep, selecting the bank which appeared less densely wooded, and always, when practicable, following the trail of the two Indians and their dog. Strain carried twenty or thirty pounds more than any other member of the party; and Castilla, the

HUTS ON FIRE.

Granadian commissioner, wishing to relieve him, offered to take the spy-glass, but on being informed that the Indians knew that this was carried by the commander, who would be selected for the first fire, he turned pale, and did not press his offer. Several of the men requested to take part of his load, but he refused, saying, that by carrying more than they, and doing more work, he could better tell how fast to march and when to halt, so as not to overtask them.

At some points the water had attained a great depth, especially where it had caught a rotary motion around some of the smaller boulders, and the traveling not only grew more difficult, but very dangerous. They had lost the Indian trail, and not being able to pass through the forest without the tedious operation of cutting a road with an ax, so thick was the undergrowth, they were forced to climb along the rocky banks of the river, to cross wide clefts in the rocks, and surmount enormous boulders, where a false step or a slip would have led to a broken limb, if not to a broken neck. They made only some ten miles the whole day, and at six in the evening, finding a defensible position, pitched their camp. The men were quite fagged out, and prepared their supper without their usual boisterous merriment. Besides, the consciousness of danger at hand made each one thoughtful. To enliven their spirits they concluded to drink up a bottle of brandy which one of the party carried for medicinal purposes, for the very sensible reason that they feared it would get broken. The evening gun of the Cyane, rising with a booming-sound over the Isthmus, also cheered them, for while that was in hearing, they did not feel themselves so entirely cut off from the outer world.

It was not so pleasant, however, when darkness enshrouded the wilderness; but the camp fires blazed brightly, and they were all brave hearts. Still many an anxious glance searched the shadowy forest that hemmed them in, and a score of musket-balls or arrows in their midst would hardly have taken them by surprise. Sentries were posted at some distance up and down the bank, to give timely warning. As silence settled on the camp imitations of the cries of wild beasts were heard in the surrounding forest, made evidently by the Indians who were hovering near, in the hope of alarming them. The next morning the boatswain's "Heave round" rung far and wide through the solitude, and the tired sleepers arose to another day's toil. On examining the ground near the camp they discovered the tracks of seven men, who had closely reconnoitred them in the night. Strain had already begun to doubt whether he was on a branch of the Savana, owing to the course which the river pursued, but as the number of cascades corresponded exactly with those laid down for that river, he was still partially satisfied, and hoped that the maps might, after all, prove to be tolerably correct.

Leaving camp about half past eight, they followed the river by the bed or banks, just as one or the other furnished best footing. Both were difficult; the former being encumbered with granite boulders, and the water often so deep as to reach nearly to the cartridge-boxes, while the latter was almost closed against them by the denseness of the undergrowth. Their constant companions, the two men and the dog, between whom and them there seemed some strange, mysterious link, still preceded them.

Passing several isolated peaks, some five or six hundred feet in height, they at noon, or in three hours and a half, had made about three miles. At length they came to some plantain fields, while the distant barking of a dog announced the proximity of Indian habitations. A halt was now called, and Strain consulted with his officers upon the best course to pursue. A long straight reach of considerable depth apparently closed the bed of the river against them in front, while on the banks the undergrowth grew so thick that it was impossible to proceed, except by the slow process of cutting a road. At length, however, they discovered a path on the left, leading over a steep hill, and which they supposed would intercept the course of the river below. Strain directed Mr. Truxton with a few men to examine it, while he, leaving the main body of the party, many of whom showed symptoms of fatigue, in an open space, where surprise would be almost impossible, continued down the river, to determine whether the reach was passable.

He found it to be, under the circumstances, and considering the evidences of a hostile spirit on the part of the Indians, a dangerous route, as the water was very deep for about a quarter of a mile, the banks on each side perpendicular and about eighteen feet in height; while the ledge at the foot of the right bank, where only they could pursue their way, was not in any part more than two feet wide, and in some places could be passed only with the greatest difficulty, and not without danger of slipping into deep water, where they would sink by the weight of their baggage and accoutrements before assistance could be rendered. An attack in such a place would prove fatal; for the Indians could fire from the bushes while they were on the ledge, where they could neither return the fire nor close with them, nor escape, except by swimming—a resort almost as fatal as to stand and be shot down. At all events, the entire ammunition of the party would be rendered useless. It was a great relief, therefore, when Mr. Truxton came down on the opposite bank and pronounced the path practicable, and trending down the valley of the river after crossing the hill on the left. Cheered by the intelligence, the party entered the river, and slowly, and with great difficulty, stemmed the deep and rapid current. Striking the foot of a steep hill on the opposite bank, they clambered up half a mile to the top, where they found a plantain field, in which the path ended. Wholly at a loss what course to take, they retraced their steps to the river, and while rattling down the hill were arrested by the barking of a dog, which was as abruptly smothered, apparently by a muzzle, and by the distant sound of axes struck rapidly upon some hollow substances. These evidences of the vicinity and watchfulness of the Indians made Strain still more unwilling to risk the ledge along the bank of the river; but as there appeared to be no alternative, he gave the reluctant order to advance, he leading the file. They steadily entered the passage, one by one, and crawling cautiously along the precipice, fortunately passed without an attack. With his gallant little band, Strain had felt himself a match for a horde of Indians; but here he was powerless, and a mountain seemed

FORDING THE RIVER

At the end of the reach they came upon a house standing a little back from the river, and surrounded by what appeared to be a species of fortification. Not wishing to expose the whole party to the risk of an ambuscade, or to alarm the natives unnecessarily, Strain ordered a halt, and advanced alone to examine it. Like all the other huts they had seen, it had evidently been recently abandoned—the proprietors having left behind much of their furniture, and some provisions scattered upon the floor. Its position was peculiar, and different from any thing they had before seen, having been erected on an artificial mound, scarped and made nearly inaccessible on all sides except through a strong gateway. This mode of construction may have been adopted to guard against inundations; but reference also appeared to have been had to defense against enemies, and the position was certainly one which a few determined men might have held against a large number. Continuing their journey, they soon arrived at a village on the left bank, containing several houses, almost concealed amidst plantain and other fruit trees. They passed this without entering, supposing it to be, like the others, deserted by its inhabitants; the only sign of life being the barking of a dog, which had probably been left when the Indians concealed themselves in the forest. Immediately in front of the village, and on a sloping shingle-beach, they found the remains of seven canoes which had just been destroyed. Their condition satisfactorily explained the sounds of the ax they had heard while in the plantain field on the hill. The destruction of these canoes was complete; for, not satisfied with splitting them up, the Indians had cut them transversely in several places, taking out large chips, rendering it impossible to repair them. This had an ugly look, and was an unmistakable sign of hostile feeling.

The river here was deep and rapid; but Strain leading the way, the whole party crossed in safety, and entered a path which appeared to follow the right bank. Advancing along this, Strain suddenly saw a party of five armed Indians rapidly approaching. Considering all the recent evidences which he had seen of their distrust, not to say hostility, his first impulse was to cock his carbine; but a moment's reflection convinced him it was better not to lose the benefit of their friendship, if it could be obtained, especially as he felt certain that he was not upon the river Savana, as he hoped and at first believed.

He accordingly halted the party, and handing his carbine to one of the men, advanced to meet them, calling out at the same time in Spanish that they were friends. The Indians then came up and shook hands, when he recognized two of their number as having been on board the Cyane soon after her arrival in Caledonia Bay. One spoke a little English, and another, who appeared to be the leader, spoke Spanish intelligibly; while the remainder, belonging to the Sucubti tribe, used only their own dialect. The leader informed Strain that he was on the Chuqunaqua instead of the Savana, but offered to guide him to the latter stream. In answer to a question respecting the distance, he replied that they could reach it in three days. Strain then inquired if he had been sent by the commander of the Cyane, or by Robinson, a chief referred to in a letter from Captain Hollins, which reached him during the second day's march. He replied, "Neither;" and did not appear to know who was meant by Robinson—probably not recognizing his English name.

Strain felt that he incurred no little risk in trusting himself to these Indians; but being firmly convinced that they were neither on the Savana nor any of its branches, and knowing that the course which the Indians pointed out would at least bring him nearer to it, he determined to accompany them, believing that he could subsist wherever they could, and that, as a last resort, he could return if they deceived or abandoned him. He was especially induced to this determination by the fact that he had offered this same Indian a large sum of money, when he was on board the Cyane, if he would guide him across, and thought it not improbable that he had determined to accept it when once free from the surveillance of his tribe. The order "Forward!" was accordingly given, and they proceeded rapidly, by a well-beaten path, through a cocoa grove and through the forest in a westerly direction. Once in the woods, and finding the path growing less distinct, Strain secretly gave orders to the officers to observe the route carefully, in order that they might return by it, if it was found necessary; and also directed Mr. Truxton, who commanded the rear-guard, to have the trees marked with a macheta as they proceeded.

In silence, and in close order, the little party rapidly followed the Indians, who, leading them over three minor ridges, and one hill nearly six hundred feet high, and through a grove of plantains and of cocoa, arrived a little before dark at a deep and gloomy ravine, through which brawled a rivulet, running apparently in the direction of the river they had left, and as the guide informed them it did.

At this place the Indians left, promising to return in the morning. To this course Strain assented with as good a grace as possible, although very much against his will; for. although he believed them sincere, he felt much more confidence in them while they were within the range of his carbine.

Some of the party asked the Indians to bring some plantains when they returned; which, after consulting with the oldest man among them, the guide promised to do. They then filed away into the woods, and the party pitched their camp. The undergrowth was cleared away, the fires lighted, and the supper of pork and biscuit quickly dispatched. Strain set the watch earlier than usual, as he did not feel perfectly

COCOA GROVE.

secure in his position, and could not shake off all suspicion of his new friends. He also ordered the fires to be made at some distance from the place which had been selected for sleeping, so as to mislead the Indians if they should attempt to surprise them, and directed the party to lie down in their ranks where the steep bank of the rivulet afforded a certain barrier against an attack in the rear. The two sentries he placed completely in the shade on each wing of the camp, and directed the officers of the guard to keep away from the fire, where the light might guide the aim of any one who should be lurking in the bushes.

Having taken all those precautions which a thorough woodsman alone understands—Strain, keenly alive to the welfare of his party, kept the watch of one of the gentlemen who was somewhat indisposed. After it was over he lay down, but at one o'clock was aroused by a slight noise on the side of the ravine whence he supposed an attack, if any, would be made. Without starting up he turned himself slowly and cautiously over, and saw some one silently climb up the bank close to where he was lying, and look round over the sleeping party. He appeared to be short in stature, as the Indians invariably are on the Isthmus, and by the dim light he could see that his hat closely resembled those which they wear, so, silently drawing his revolver, he thrust it suddenly against his side, saying, in a low tone, "Who's there?" He was answered by Mr. Truxton, just in time to prevent his firing. It was this officer's watch, and I having heard a noise in the ravine, he had gone down to investigate it, and was returning by the bank when he thus unexpectedly encountered Strain, and came near losing his life. A moment's delay in answering would have insured his death.

This little circumstance, which was unknown both to the sleepers and sentries, was the only alarm they had during the night. On the morning of January 26th, about half past eight, the guide returned, and announced himself ready to continue the journey. Strain was somewhat surprised to find that, excepting the interpreter and guide, the rest, numbering four, were new Indians.

No plantains were brought as promised; but they continued to give every evidence of friendship, and advised the party to supply themselves with water from the rivulet, as they would have a long and severe march before they reached any more. They therefore filled their bottles and flasks, and, after taking a hearty drink, commenced following a path leading in a westerly direction over a very steep hill about 800 feet in height. Resting but once, and only for a few minutes, to recover their breath, they reached the summit, from which could be seen many ranges and peaks, still higher, to the northward, forming apparently a chain of isolated mountains. Hurrying down the opposite slope, which led them at times along the margin of deep valleys with almost perpendicular sides, they reached, about half past ten, another ravine containing water, where they halted to refresh themselves, not having drank since leaving the camp in the morning. In this rapid march Strain had a fair opportunity of testing the comparative endurance of his men and the Indians; and although the latter, being nearly naked, and with no burdens except their arms, took the steep ascents much better than the former, he found his own men fully equal to them, heavily laden as they were, in descending or on level ground.

Having slaked their thirst at this stream, which Strain concluded to be that called the Asnati on the old Spanish maps, they pushed on, and soon after, passing another branch of the same stream, and some plantations of plantains and cocoa, commenced ascending another steep hill, still pursuing a course little to the northward of west. Near this point, and in the valley, a village known as Asnati is supposed to be situated; but the Indians were always careful to carry them as far as possible from their habitations. The hill which they now ascended was neither so steep or high as the last one, not being more than 450 feet above the level of the valley from which they started. While ascending it, one of the men, Edward Lombard, a seaman of the Cyane and who carried the boatswain's whistle, was stung on the hand by a scorpion, and for some time suffered severely. Truxton had a little brandy left in a flask, and Strain having heard that stimulants were good for poison, told Lombard to drink it. But the latter being a temperance man declined. Strain then ordered him to swallow it, threatening, if he refused, to pour it down his throat. The poor fellow finally swallowed it, and some moistened tobacco being applied to the wound he soon began to rally, and was at length able to proceed slowly, and by night had recovered entirely, and was as active and energetic as before. He said the effects of the sting were like an electric shock, as instantaneous and as paralyzing. While Lombard was suffering and unable to walk, the whole party halted, and Strain asked the Indians if they knew of any remedy for the sting. They replied they did not; but that there were men in their village who could cure it.

Strain, taking Lombard's musket, gave the order "Forward!" and passing the summit of the hill they commenced the descent, when they were suddenly met by some five or six Indians. A halt was made, and a man, who appeared to be a chief, approached Strain, and made an elaborate speech, accompanied with all the gesticulation and vehemence of an Indian orator. He concluded by directing the guide to interpret it. During the continuance of this speech, of which Strain could distinguish but one word, "Chuli"—"No"—he carefully watched the countenance of the guide, and thought he could detect an expression of annoyance not unmingled with contempt. The latter would not interpret the speech, though requested to do so both by the orator and Strain. At length, being urgently pressed, he abruptly replied, "Vamos"—"Let us go"—and led off. While descending the hill, most of the strange Indians, taking with them some of the party with which they had started in the morning, and replacing them with others, left. From that time the conduct of the Indians changed.

At the foot of the hill they arrived at a ravine leading nearly west, which they followed until sunset, sometimes climbing over boulders, and at others sliding down the face of smooth rocks, where the rivulet formed cascades, and always traveling rapidly and most laboriously. From time to time Strain was obliged to order a halt, to allow those who were most fatigued a little rest. The Indians who had joined that day appeared to enjoy the distress of the men amazingly, and attempted to hurry them on before they were sufficiently rested. Mr. Polanco, one of the New Granada commissioners, laid down, utterly prostrated by fatigue; and Mr. Kettlewell, engineer and draughtsman of the expedition, who was ill the night before, wished the party to leave him to rejoin them afterward at the next camp. Having made only twelve miles, they arrived about sunset at a stream a little smaller than the one they had left two days before, and encamped on an island in front of a plantain grove. The difficulties of the way may be gathered from the fact, that, to make even this short distance, the men were kept all day to the top of their speed and endurance. The whole march was a constant climbing, sliding, floundering over one of the most broken countries imaginable. The ravine which they had traveled was, by common consent, denominated "the Devil's Own." Before the Indians left that evening, the guide, who had appeared somewhat depressed since the interview with the strange Indians, informed Strain that, in the morning, he should start on his return to Caledonia Bay; and that he would visit the ship, and tell the Captain how well they had progressed; meanwhile, he would leave behind some of his friends, to guide them to the Savana, at which they would arrive in a day and a half.

Strain attempted to dissuade him, offering him any pay he might ask to guide him through; but to no purpose. He then told him that he would send a letter by him to Captain Hollins, which he declined taking, and started with the others, leaving Strain with no very pleasant anticipations for the future, there being seven days' hard march between him and the ship, while it was very doubtful whether he could find the path back; for in many places it was so obscure that the Indians themselves could with difficulty follow it. A fatigued party, who looked back with horror to the last few days' march, and with less than one day's provisions, and very doubtful guides, was not a very pleasant object to contemplate. Believing that there was a large Indian population immediately in the neighborhood, Strain ordered an unusually strict watch to be kept. Still he had pitched the camp in so strong a position that he did not believe they would dare to attack him.

The next morning, while preparing breakfast, two strange Indians, with quite a small boy, strolled into camp; and soon after, the old guide, and several others, among whom were the new guides, of forbidding appearance, and who were besides armed with bows and steelpointed war-arrows—which they never use in hunting—also came in. Some forty more, of different ages and sexes, were seen skulking in a plantain patch on the opposite side of the river, and narrowly watching every movement. Those who were in camp were exceedingly anxious to look into the haversacks of the men and ascertain the amount of provisions they had. These, it is true, were scanty enough, as many of the men had used theirs imprudently, and the New Granadian commissioners, having either consumed or thrown away their rations, had none at any time after crossing the mountains, but lived entirely on those of other members of the party. The officers still having some provisions, which, with greater prudence, they had reserved, Strain directed that they should be divided with the men. All cheerfully consented, with the exception of one, who could not understand why those who had stinted themselves to provide food for the future should now be made to suffer for the reckless improvidence of the others. Strain, who cared little for meat, had eight pounds preserved, all of which he gave up to the men. This left them with nothing on hand but a little bread dust and two or three pounds of coffee. Still, if the Indians fulfilled their promise and took them to the Savana in a day and a half, and they could there obtain boats, they would make a fair journey and escape without great suffering.

Before setting out, Strain took the old guide aside and endeavored to obtain a clew to their intentions and his own prospects. But the frankness and apparent sincerity of his demeanor were gone. He now stated that he would not return to Caledonia Bay until next month, which was only a subterfuge to avoid being pressed to carry a letter. Strain then renewed his offer of large pay, if he would continue to act as guide; and finally asked him his motives in coming thus far. To this he replied, that he had taken an interest in him when they met on board the Cyane, and did not wish him to follow the Chuqunaqua, which was a very long route to the Pacific. He still declared that they would reach the Savana in a day and a half, and the harbor of Darien in two days and a half; but Strain could not induce him to give the name of the river on the banks of which they then were. He then broached the subject of provisions, and asked him if they could not procure some plantains, offering to pay exorbitantly for them. Being told he could not, he requested that he would ask his friends to give them some, reminding him, at the same time, that in compliance with their promise, they had never taken a single article belonging to the natives. To this he assented, but refused either to give or sell. Strain then told him that if they should become short of provisions, and the Indians would neither sell nor give the fruits which were rotting on the trees, in justice to his own party, he should be obliged to violate his promise and help himself. To this threat the guide made no answer. Finally, Strain offered him money for his past services, which he positively refused to accept; and soon after, as the party was about to set out with their new guides, the former turned to take leave of him, and found he had disappeared. This was a bad omen, as the natives on this Isthmus have a strong taste, whether natural or acquired, for shaking hands when their intentions are friendly.

Setting out under these unpleasant auspices, they followed their guides, who led them rapidly by a trail over a hill and through the forest again, to and down the bed of the river. When about a mile below the camp, Strain was anxious to speak with them, but they would not stop, and were careful to keep some one hundred yards in advance—imagining that at that distance they were out of the reach of their fire-arms. They appeared determined to allow no time for rest, which the lagging of some of the party soon showed the need of; for the climbing over rocks, and floundering through reaches of deep water, at the rapid rate they went, tasked to the utmost the heavily-laden party. At length they struck off from the river, taking a path which led into the wood in a westerly direction. From the moment they left the river nothing more was seen of them. Strain's suspicions were immediately aroused, yet he continued to follow the path for about a mile, when it terminated at a plantation and recently abandoned rancho. Here he halted his men, and waited some time to see if the Indians would return. Finding they did nor, he hallooed for them. Receiving no answer, he gave the order to countermarch. Disappointed and baffled, the party slowly and with difficulty succeeded in finding their way back to the bed of the river.

The treachery of the Indians now being evident to the whole party, and hence their whereabouts encompassed with doubt, Strain called the first and last council which he held in the expedition. This was composed of all the officers, the two New Granadian commissioners, and the principal engineers of the party. The maps were brought out and spread before them, and Strain explained to them their position, as he understood it. According to the statement of the first guide, in whom they still had some little confidence, they had left the Chuqunaqua, and were within one and a half day's inarch of the Savana; and as there was but one river of any importance laid down on the maps, the Iglesias, which entered the Savana near its mouth, he naturally concluded he was on that river. Besides, this view made the statements of the Indians and the different maps in his possession corroborate each other. On the one drawn by Mr. Gisborne, ranges of hills were put down between the Chuqunaqua and Iglesias, which corresponded to those which they had just traversed. The great object was, if possible, to reach

FIRST AND LAST COUNCIL.

the Savana; but the question arose, whether the risk might not be too great to justify the attempt. The distance was not supposed to be very great, but there was no trail to direct their course, so that they would probably have to cut a path the whole of the way. The journey, therefore, instead of occupying a day and a half, might take weeks.

Besides, there was no certainty of finding water on the route, as it was near the end of the dry season, and they would thus perhaps become embarrassed in the wilderness, and perish from hunger and thirst. To effect this seemed to be the object the Indians had in view in leading them away from the river; while, even should they reach the Savana, they would meet no canoes, as the savages who had abandoned them would take care to conceal or destroy them all. The only resource then left would be to make their way for more than forty miles through one of the most impenetrable mangrove swamps in the world, where half a mile would he a hard day's journey. In addition to all this, Strain was also aware that, owing to the slight fall in the bed of the Savana, the tide ascended the whole length of these swamps, so that they might perish for want of fresh water while following its marshy banks. In a mangrove swamp, too, they could not expect to find game, or get it if they did. Neither could they dream of finding timber with which to construct a raft. As if to nail all these arguments for not attempting to reach the Savana, two or three of the men and the junior New Granadian commissioner were already foot-sore and worn out with fatigue, and should they break down entirely, or should any body fall sick, it would be impossible to carry them through the dense forest which they would have to traverse. On the other hand, whether the river they were on was or was not the Iglesias, one fact remained certain, that however tortuous might be its course, it would eventually lead to Darien Harbor, the common receptacle for all the streams in that region. As long as they continued on its banks they could not, at any rate, suffer from thirst, at least until reaching tide-water, which did not run so far inland on any of the Darien rivers as on the sluggish Savana. Until meeting tide-water they would encounter no mangroves to impede their march, and if they should, could return a short distance to the forest growth of timber and construct rafts to convey them through.

On the contrary, if this river, notwithstanding the assertions of the Indians, should prove to be the Chuqunaqua, they would meet with settlements before arriving at the mangrove swamps, which presented the most formidable obstacle to reaching the Pacific shore.

The best chance for game was on the river, where some fish might also be obtained, while there was every reason to believe that, as on the stream they had left, they would find plantains and bananas. These last Strain had already determined no longer to respect, considering that the treachery of the Indians and their refusal either to sell or give had entirely relieved him from his former promise. Finally, by keeping on the river, should any of the party fall ill, they could, as a last resource, always construct a raft for their conveyance, even if they failed in finding canoes farther down, which they hoped to do.

This imposing council was held upon a shingle beach, upon which Strain sat soaking his hard, dry boots in the water while making his final speech. The different members were scattered around, some drinking water and others smoking, listening with the gravity of Indian chiefs to this lucid exposition of these not very flattering prospects. After he had finished, he invited every one to express his opinions freely. Unlike most councils, no one was found in this to suggest objections, and Strain took a vote on the two alternatives, when it was unanimously determined that they should continue down the river on which they then were.

No proposition was made to return to the ship, nor was it hinted at by any one.

To those easily discouraged—if there were any—the obstacles already surmounted must have appeared too formidable for them to wish to grapple with them a second time; while, as far as one could judge, the idea of a return occurred to very few members of the party. If it had been otherwise Strain would have pushed on, for, to quote his own language, he said, "I neither considered it expedient or consistent with our national and personal reputation, that so formidable a party, and one which so much was expected, should be turned back by trifling obstacles."

Of the seven persons who voted at this council, two perished during the journey, and one afterward, from the effects of starvation and fatigue.

At this point the reader would naturally wish for some clew to unravel the tangled state of things, and know definitely where the party really were, and obtain some explanation of the conduct of the Indians. The river which they had followed for several days after crossing the Cordillera, Strain eventually ascertained to be the Sucubti, a very important stream, utterly ignored in those maps of the moon which Dr. Cullen and Mr. Gisborne—the latter backed by the highest English authority—had published. The Indian guide whom they met on the Sucubti stated that this river was the Chuqunaqua, and that to follow it was a very long route to the Pacific. This, though not literally true, was so in effect, for while it was not the Chuqunaqua, it was a tributary of that river, which certainly did prove to be the most tedious and toilsome route. The river on which they now was the Chuqunaqua, one of the most tortuous known to geographers—in fact, by looking at the map, one will see that it would be almost impossible to double up a stream so as to get more length in the same space. To all Strain's inquiries respecting the name of this river, he could get no other reply than "Rio Grande"—the great river. He therefore remained in utter ignorance respecting it, although, if he gave any credit whatever to the statements of his first Indian guide, that the Sucubti was the Chuqunaqua, he would naturally conclude that they were upon the next river to the westward of it, which was laid down by Mr. Gisborne as the Iglesias. On the whole, Mr. Strain was afterward convinced that the Caledonia Indians and their Sucubti friends intended to lead them by the most direct route to the Savana, and that they were prevented from doing so by the Indians of the Chuqunaqua or Chuqunas, whom they met on their seventh day's march, and who from the first created suspicion. This opinion, which was originally founded upon the conduct of the respective parties, was farther corroborated by the report of a journey made by a Spanish officer in 1788, from the fort of Agla, near Caledonia Bay, to Puerto Principe, on the Savana. He set out under the guidance of the chief of the Sucubti village, who conducted him safely across, cautiously avoiding the Chuquana Indians, who were hostile to the Spaniards. He was prevented from returning, owing to the hostility of this tribe.

It would appear that in 1788, as in 1854, the Chuqunas were on friendly terms with the Indians of the Caledonia and Sucubti valleys, probably on account of their commercial relations, but that the latter have not sufficient influence to obtain a passage for a white man through the territory of these intractable savages. To these Indians is attributed the massacre of the four men in the British expedition.

It afterward turned out that when they struck the Chuqunaqua river, they were within five miles of the road cut by this British expedition before it turned back. At first sight, by looking at the map, it may appear a most unfortunate circumstance that this road could not have been struck, as they might easily have cut their way to it. Still it is very doubtful if they could have followed the Savana without canoes—owing, as before remarked, to the impenetrable mangrove swamps that stretched so far up with its tides into the interior—and they would have been compelled at last to return to the Chauqunaqua.

It is true that from the termination of Prevost's road to the mouth of the Lara, where the English civil engineers in the service of the Atlantic and Pacific Junction Company had established a station for the purpose of surveying the river, was but six miles; yet, as they were unaware of that circumstance, it could not have influenced their determination. A man with a thousand leagues of wilderness before him may be within one mile of deliverance, yet, with the facts in his possession, to go in that direction would be downright infatuation. The maps on which Strain had implicitly relied proved utterly trustless. The Indians were no better than Gisborne's maps; and thrown wholly upon his own resources, he had, from the meagre facts in his possession, to determine what course to pursue. To have gone in search of a road of whose existence he was ignorant, or to have followed the banks of the Savana toward impassable swamps to find a station he had never heard of, would have been the act of a madman. Under the circumstances he took the wisest course beyond a doubt.

After having determined to continue down the river, Strain felt it important to impress on the men the necessity of great frugality in the use of provisions. He endeavored to prove to the sailors and other members of the party, that the idea that men needed such a liberal supply of food was entirely a popular fallacy; and in order to give his views a more practical bearing, declared that a man could live very comfortably three days without food, and eight with very little suffering. The men rolled their tobacco quids in their mouths, and tried to look their assent to this entirely new doctrine promulgated there on the Isthmus, in the midst of famine, but it was evident Strain could not count much on his converts. The resolution to go on being made, the order to march was given; and now, without a guide, they wound down the crooked banks of the stream.

Soon after leaving the place where the council was held, they passed a river which entered from the eastward, and which corresponded with one put down on Mr. Gisborne's map as an upper branch of the Iglesias.

Subsequent investigations led to the belief that this river was the Asnati (see chart), which Colonel Codazzi in his recent maps has shown to be a branch of the Sucubti, upon information compiled from old Spanish manuscripts, and from conversations held with the Indians. During the afternoon a few plantains were found by the men, and urged upon Strain, who refused, wishing the men to keep them. He and Truxton killed eight birds during the day (though one was an owl and another a woodpecker), which were divided among the party, and none felt the want of the ration, which had given out. This was the first time Strain had fired his carbine at game, and the men, seeing what a dead shot he was, requested him to shoot for the party. While their pieces were echoing through those rarely trod solitudes, a little incident occurred which caused a thrill of feeling to pass through the band. On looking up they saw a large flock of birds high in the air, and sweeping with great velocity to the west. Down in the forest all was still, but far up heavenward the trade-wind was fiercely blowing, and on the wings of the gale those birds were drifting to the Pacific, now the goal of their own efforts, and the only hope of their salvation. An unknown and toilsome way was before them, while those buoyant forms, borne apparently without effort on, would soon feel the spray of the Pacific. Many an envious glance and envious wish was sent after those birds in their flight. Still the party kept up good spirits, and whiled away the time with jokes and stories. At this camp, and that of the night before, they were first annoyed by sand-flies, and this was the first camp where they met mosquitoes. Fire-flies, too, filled the wood, enlivening the otherwise monotonous gloom. The next morning, January 28th, at half past eight, they continued their journey, and although they had no provisions on hand the party was in fine spirits. The river widened and deepened in parts so much that they were obliged to cut their way across some bends through the undergrowth of the forest. Mr. Truxton shot three birds and caught some fish—among them one cat-fish, six inches long. In the afternoon they had come upon a plantain and banana field, and after eating as many ripe ones as they could obtain, filled their haversacks. Finding that Messrs. Castilla and Polanco, the Granadian commissioners, were very much fatigued, they encamped at about half past three, having made only about five miles. In this camp mosquitoes and sand-flies were met in swarms; and for the first time they heard, what is familiar to every woodsman, the falling of forest trees alone, resembling in the distance the reports of guns.

On the morning of the 20th they left camp at nine o'clock, many of the party with legs and hands much swollen from the bites of mosquitoes and sand-flies, and one of the engineers completely speckled with their bites and badly swollen. About two miles from camp they found some dilapidated huts, which had evidently been deserted for a long time, and fields of plantains and bananas. As the Chuquna Indians apparently do not frequent this portion of the country, these plantations probably owe their origin to the Spaniards, who had a garrison in this vicinity about the middle of the last century.

In the afternoon Corporal O'Kelly and Strain together shot a large iguana on the opposite bank of the river, which sunk. Holmes (landsman) jumped in to bring it ashore, but finding the water deeper than he anticipated, he threw off one of his boots, which sank to the bottom. The recovery of this was of more importance than the iguana, and after feeling around for it in vain, one of the men stripped and dived again and again for it, but unsuccessfully, its dark color rendering it invisible. To this apparently trivial circumstance this poor fellow's death after was partly attributable. This was Sunday. Fatigued with the weight of plantains and bananas, which filled every haversack, and with climbing through gulches and struggling through thickets, they went into camp about four o'clock, having accomplished, with hard work, a distance of only seven miles and a half. Opposite to the camp was a plantain field, with its whole vicinity swarming with mosquitoes of such enormous size, that the officers jocosely christened it "The camp of the mosquitoes elephantes." This afternoon Strain took off his boots for the first time since

FISHING FOR THE BOOT.

starting. It required the efforts of two men to remove them. His feet were very much lacerated, as were also those of the party. The linen shirt which he had put on under his woolen one was now of great service, and Strain tore it up by piecemeal to bind up the wounds, which otherwise would have been dreadfully aggravated.

On the morning of the 30th, after plucking a supply of plantains and bananas from the plantation opposite, they set out on their journey down the river, which now had become so deep that fording was difficult, and they were obliged to hew their way along the banks, and in some cases saved much distance by cutting directly across the bends. About mid-day, being on the left bank, and finding an opportunity to ford, they crossed, as Strain deemed it decidedly best that they should be upon the west side, and between it and the Savana, where, if by accident they should get away from it, they might strike the latter river. During the day a snake about eighteen inches long was killed, which Mr. Castilla said was the coral snake, and very venomous. Strain doubted this, as he had seen such before in Brazil, and found them harmless.

At about three o'clock they encamped on a mud bank, the Granadian commissioners declaring they could go no farther. The day's journey, it is true, had been fatiguing, yet the principal labor, which was cutting the road through the dense undergrowth, Mas performed by the officers and their men. Mr. Truxton shot a crane just at evening, which was given to the men, some of whom, owing to carelessness and improvidence, were out of provisions. At this camp they thought they discovered tidal influence, and were greatly elated. Camping so early left a long afternoon, and those less fatigued resorted to various amusements to pass the time. One man, named Wilson, had a superb voice, and he made the woods echo with negro songs—"Ole Virginny" and "Jim Crow;" and often during the day his comic songs would bring peals of laughter from the party, and discordant choruses would burst forth on every side. Another had made a fife out of a reed, which he played on with considerable skill, and made the camp merry with its music. The next morning they breakfasted leisurely, and at half past eight commenced again their journey. Having been so successful the day before in cutting off bends by pursuing a fixed compass course through the woods, they set off S.W. by W., and after crossing a bayou with some difficulty, met a deep and turbid river, about seventy feet in width, running from west to east, which they crossed on a large tree. This river was known on the old Spanish maps as La Paz, and enters the Chuqunaqua nearly opposite the embouchure of the Sucubti, which was thus passed without being seen. A few hundred yards farther on they again fell in with the Chuqunaqua, which had suddenly become deep, rapid, and much more turbid than where they had left it two miles above. Encouraged by the result of this experiment, they again took a departure from the river, and pursued a S.W. by W. course through a swampy country, where, although it was the height of the dry season, they were obliged to make many détours to avoid the standing water and muddy bottom. The country being generally open, they marched rapidly, those behind shouting "Go ahead," as the engineer reported southwest by west southwest. As they tramped along, Strain saw a buzzard sitting on a tree. Turning to Lombard, he asked him if buzzards were good to eat. Lombard being decidedly low in the larder, and withal having a strong appetite for flesh, replied—"Yes, captain, any thing that won't kill will fatten." Strain thereupon fired and dropped the buzzard, and advanced to pick him up. But as he drew near, the dreadful effluvia which this bird sends forth made him turn aside. Lombard approached somewhat closer, but at last was compelled to wheel off also. Each man in his turn, tempted by so fine a bird, pushed for the prize, but each and all gave him a wide berth. In the end they became less fastidious. Avoiding the thick undergrowth instead of cutting through it, and returning to their course when it was passed, they by twelve o'clock had made about four miles and a half. Not meeting the river, the course was changed to S.W., at 3.15 to S.S.W., and from 3.45 to 4.15 to S. by E., when they fell in with a pebbly ravine, containing cool and palatable standing water. As the distance to the river was uncertain, the probability of obtaining water in advance too vague to be risked, and many of the men foot-sore and fatigued, Strain determined to encamp there, although the sun was several hours high. Most of the men had no plantains and bananas, while the officers' messes contained only three or four, so that it now became necessary to examine into the resources which the forest afforded. Some palmetto or cabbage-palm, resembling, but not identical with, that which grows in Florida, was found, and as Strain, on a previous journey into the interior of Brazil, had lived some ten days on a similar vegetable, he had no hesitation in recommending it to the party, and set the example by eating it himself. This is not a fruit, it is simply the soft substance growing upon the top of a tree, and can be cooked like a cabbage. The palmetto of Darien is more bitter and less palatable and nutritious than that of Brazil, but the bitterness was partially removed by frequently changing the water in boiling.

Very little was said in this camp, and there was no mirth or pleasantry; on the contrary, a gloom for the first time seemed to rest on the party. They lay scattered around among the trees, talking in low tones or musing. It was evident they missed the companionship of the river, the only thread that connected them with the Pacific, and the last object at night and the first in the morning on which their eyes rested. Even Strain felt its influence so much, that when the draughtsman, Mr. Kettlewell, came at a late hour of the night to him, stretched on the ground in the smoke from the watch-fire to escape the bites of mosquitoes, and asked what he would have the camp named, he replied the "Noche triste"—the "sad night;" and although many other camps afterward were far sadder than this, and more deserving the title, he nevertheless allowed this name to remain, for it proved the beginning of sorrows. In the morning Strain and Maury took a long walk in the woods to examine them, and held a protracted and serious conversation over their condition and prospects, and discussed the project of making a boat.

Starting about half past eight, they struck off on a southeast course, anxious to reach the river. Hitherto Strain had led the party, every day cutting a path with his cutlass. This was most laborious, and Mr. Truxton now insisted upon taking the macheta, and going ahead in his place. The undergrowth was exceedingly dense, and composed, for the most part, of pinnello—little pine—a plant resembling that which produces the pine-apple, but with longer leaves, serrated with long spines, which produced most painful wounds, especially as the last few days' march had stripped the trowsers from many of the party. After cutting for some time, he suddenly fell backward, and almost swooned away from the effects of heat, pain, exertion, and fatigue. Strain now saw that he was in danger of over-tasking the officers, and detailed two men to cut the path, they being relieved every hour. The rest would sit down till ordered to march. It would take hours to cut a few rods.

This was the severest traveling yet, beating, as Strain declared, the jungles of Brazil and the East Indies, which he once considered without a rival. When they encamped, at half past four, near a ravine containing standing water, they had not advanced more than two miles, or at an average only eighty rods an hour. During the march they fell in with palm-trees, bearing a nut which they found edible, agreeable to the taste, and nutritious, though so hard as to be masticated with difficulty. They cut down two trees, and Strain divided the nuts equally. Some palmetto was also found, and toward evening Strain was so fortunate as to kill a mountain hen, which was divided between the two officers' messes, as the men had the last bird which was shot. A deer was also started—the first seen—but they could not get a shot at it.

So thick was the undergrowth that it required some time to clear away a place sufficiently large for a camp. Into this crater, as it were, hewn out of the foliage, the tired wanderers, after a frugal supper, lay down, filled with gloomy anticipations, and, strange as it may seem, mourning most of all for the lost river, which had so suddenly changed its direction and gone off no one knew whither.

Edward Lombard, an old seaman and former shipmate of Strain, whose boatswain's whistle had each morning piped the "heave round," and who had shown great energy and activity throughout, now became quite ill and desponding. A little soup, however, and meat of the mountain hen, which Strain gave him from his own mess, appeared to revive him. During his whole life he had been accustomed, on board ship, to a large supply of animal food, and with it he could have endured as much fatigue as any one in the party; but without it, he was perfectly prostrated. Ever afterward, until his death, the state of his health was an indication of the quantity of animal food in camp. There were no songs to-night—the last strain of music dying away in the "Sorrowful camp." The distressed commander of this handful of brave men now began to feel the pressure of their fate upon him, and on this night he was kept awake by the groans of those who were suffering from sore feet and boils. But fatigue finally overcame all; and at midnight no one was awake, except the sentries and officer of the guard.

Next morning, February 2d, the party appeared in pretty good condition; and Lombard, after eating a banana which Strain had reserved, and which was the last one remaining in the party, declared himself stronger, and ready to start.

Having thus far failed to reach the river on a southeast course, Strain changed it to east; for he found that the great majority of the men thought only of reaching the river banks. "Oh for the river!" exclaimed one; "it is better than Darien harbor." Fearful lest the supplies of water they had hitherto found so abundant might fail, Strain now directed the few vessels which they had remaining to be filled, and given in charge of the officers, he himself carrying an India-rubber canteen containing about half a gallon, which he served out from time to time to the party. As they groped their way through the wilderness, they came upon trees of enormous size, one of which would have measured forty-five feet in girth.

During the afternoon Strain became somewhat anxious in regard to the supply of water, as many hours had elapsed without meeting with water-holes, and their vessels were empty. He therefore deviated from his course still more to the northward to follow down a slope, and finally meeting a dry ravine, where he thought, as a last resort, he could obtain water by digging, followed it until they met water-holes. Here, although but four o'clock, they encamped, and had quite a feast on the turkeys and small birds, reserving a monkey Strain had shot for breakfast. On this and on all subsequent occasions, all game or fruits obtained was divided equally among the party. Poor Lombard was at last unable to chew tobacco, and brought all he had left—about ten ounces—and gave it to Strain, saying, "Here, captain, take what there is left; I can't chew any more." A little coffee remained, and in order to eke it out as far as possible, the berries, after one steeping, were packed up for a second—then for a third, and, finally, for a fourth, when they were eaten for food.