Democratic Ideals and Reality: A Study in the Politics of Reconstruction/Chapter 3

III

THE SEAMAN'S POINT OF VIEW

The physical facts of geography have remained substantially the same during the fifty or sixty centuries of recorded human history. Forests have been cut down, marshes have been drained, and deserts may have broadened, but the outlines of land and water, and the lie of mountains and rivers have not altered except in detail. The influence of geographical conditions upon human activities has depended, however, not merely on the realities as we now know them to be and to have been, but in even greater degree on what men imagined in regard to them. The ocean has been one throughout history, but for effective human purposes there were two oceans. Western and Eastern, until the Cape of Good Hope was rounded only four hundred years ago. So did it happen that Admiral Mahan in the closing years of last century could still base a new message in regard to sea-power on a text from the first chapter of Genesis. The ocean was one ocean all the time, but the practical meaning of that great reality was not wholly understood until a few years ago—perhaps it is only now being grasped in its entirety.

Each century has had its own geographical perspective. Men still living, though past the age of military service, were taught from a map of the world on which nearly all the interior of Africa was a blank; yet last year General Smuts could address the Royal Geographical Society on the German ambition to control the world from the now explored vantage-ground of Central Africa. The geographical perspective of the twentieth century differs, however, from that of all the previous centuries in more than mere extension. In outline our geographical knowledge is now complete. We have lately attained to the North Pole, and have found that it is in the midst of a deep sea, and to the South Pole, and have found it upon a high plateau. With those final discoveries the book of the pioneers has been closed. No considerable fertile new land, no important mountain-range, and no first-class river can any more be the reward of adventure. Moreover, the map of the world had hardly been sketched before claims to the political ownership of all the dry land had been pegged out. Whether we think of the physical, economic, military, or political interconnection of things on the surface of the Globe, we are now for the first time presented with a closed system. The known does not fade any longer through the half-known into the unknown; there is no longer elasticity of political expansion in lands beyond the Pale. Every shock, every disaster or superfluity, is now felt even to the antipodes, and may indeed return from the antipodes, as the air waves from the eruption of the volcano Krakatoa in the year 1883 were propelled in rings over the Globe until they converged to a point in the opposite hemisphere, and thence diverged again to meet once more over Krakatoa, the seat of their origin. Every deed of humanity will henceforth be echoed and re-echoed in like manner round the world. That, in the ultimate analysis, is why every considerable State was bound to be drawn into the recent War, if it lasted, as it did last, long enough.

To this day, however, our view of the geographical realities is coloured for practical purposes by our preconceptions from the past. In other words, human society is still related to the facts of geography not as they are, but in no small measure as they have been approached in the course of history. It is only with an effort that we can yet realise them in the true, the complete, and therefore detached, perspective of the twentieth century. This War has taught us rapidly, but there are still vast numbers of our citizens who look out on to a vivid Western foreground, but only to a very dim Eastern background. In order therefore to appreciate where we now stand, it will be worth while to consider shortly the stages by which we have arrived. Let us begin with the succeeding phases of the seaman's outlook.

Imagine a vast tawny desert, raised a few hundred feet above the sea level. Imagine a valley with precipitous rocky slopes trenched into this desert plateau, and the floor of the valley carpeted with a strip of black soil, through the midst of which winds northward for five hundred miles a silvery navigable river. That river is the Nile flowing from where the granite rocks of Assouan break its navigability at the first cataract to where its waters divide at the head of the Delta. From desert edge to desert edge across the valley is a crow-fly distance of some ten or twenty miles. Stand on one of the brinks with the desert behind you; the rocky descent falls from your feet to the strip of plain below, and away over the floods of the summertime, or the green of the growing

Fig. 1.—A river-world apart. winter-time, or the golden harvests of the spring, you are faced by the opposing wall of rock rising to the other desert. The recesses in those rock fronts were carved long ago into cavernous temples and tombs, and the salients into mighty effigies of kings and gods. Egypt, in this long sunken belt, was anciently civilised because all the essential physical advantages were here combined for men to work upon. On the one hand were a rich soil, abundant water, and a powerful sunshine; hence fertility for the support of a population in affluence. On the other hand was a smooth water-way within half a dozen miles or less of every field in the country. There was also motive power for shipping, since the river-current carried vessels northward, and the Etesian winds—known

Fig. 2.—A coastal navigation drawn to the same scale as the river navigation opposite. on the ocean as the trade winds—brought them southward again. Fertility and a line of communications—man-power and facilities for its organisation; there are the essential ingredients for a kingdom.

We are asked to picture the early condition of Egypt as that of a valley held by a chain of tribes, who fought with one another in fleets of great war-canoes, just as later tribes have fought on the river Congo in our own time. Some one of these tribes, having defeated its neighbours, gained possession of a longer section of the valley, a more extensive material basis for its man-power, and on that basis organised further conquests. At last the whole length of the valley was brought under a single rule, and the kings of all Egypt established their palace at Thebes. Northward and southward, by boat on the Nile, travelled their administrators—their messengers and their magistrates. Eastward and westward lay the strong defence of the deserts, and at the northern limit, against the sea pirates, a belt of marsh round the shore of the Delta.[1]

Now carry your mind to the 'Great Sea,' the Mediterranean. You have there essentially the same physical ingredients as in Egypt but on a larger scale, and you have based upon them not a mere kingdom but the Roman Empire. From the Phœnician coast for two thousand miles westward lies the broad water-way to its mouth at Gibraltar, and on either hand are fertile shorelands with winter rains and harvest sunshine. But there is a distinction to be made between the dwellers along the Nile banks and those along the Mediterranean shores. The conditions of human activity are relatively uniform in all parts of Egypt; each of the constituent tribes would have its farmers and its boatmen. But the races round the Mediterranean became specialised; some were content to till their fields and navigate their rivers at home, but others gave most of their energy to seamanship and foreign commerce. Side by side, for instance, dwelt the home-staying, corn-growing Egyptians and the adventurous Phœnicians. A longer and more sustained effort of organisation was therefore needed to weld all the kingdoms of the Mediterranean into a single political unit.

Modern research has made it plain that the leading seafaring race of antiquity came at all times from that square of water between Europe and Asia which is known alternatively as the Ægean Sea and the Archipelago, the 'Chief Sea' of the Greeks. Sailors from this sea would appear to have taught the Phœnicians their trade in days when as yet Greek was not spoken in the 'Isles of the Gentiles.' It is of deepest interest for our present purpose to note that the centre of civilisation in the pre-Greek world of the Ægean, according both to the indications of mythology and the recent excavations, was in the Island of Crete. Was that the first base of sea-power? From that home did the seamen fare who, sailing northward, saw the coast of the rising sun to their right hand, and of the setting sun to their left hand, and named the one Asia and the other Europe? Was it from Crete that the sea-folk settled round the other shores of the Ægean 'sea-chamber,' forming to this day a coastal veneer of Greek population in front of peoples of other race a few miles inland ? There are so many islands in the Archipelago that the name has become, like the Delta of Egypt, one of the common descriptive terms of geography. But Crete is the largest and most fruitful of them. Have we here a first instance of the importance of the larger base for sea-power? The man-power of the sea must be nourished by land- fertility somewhere, and other things being equal—such as security of the home and energy of the people—that power will control the sea which is based on the greater resources.

The next phase of Ægean development teaches apparently the same lesson. Horse-riding tribes of Hellenic speech came down from the north into the peninsula which now forms the mainland of Greece, and settled, Hellenising the earlier inhabitants. These Hellenes advanced into the terminal limb of the peninsula, the Peloponnese, slenderly attached to the continent by the isthmus of Corinth. Thence, organising sea-power on their relatively considerable peninsular base, one of the Hellenic tribes, the Dorians, conquered Crete, a smaller though completely insular base. Fig. 3.—The Greek Seas, Ægean and Ionian, showing the Cretan insular sea-base, and the Greek peninsular sea-base; also the march of Xerxes to outflank the sea-power of Athens.

To the eastern, outer shore of the Ægean the Persians came down from the interior against the Greek cities by the sea, and the Athenian fleet carried aid from the peninsular citadel to the threatened kinsfolk over the water, and issue was joined between sea-power and land-power. A Persian sea-raid was defeated at Marathon, and the Persians then resorted to the obvious strategy of baffled land-power; under King Xerxes they marched round, throwing a bridge of boats over the Dardanelles, and entered the peninsula from the north, with the idea of destroying the nest whence the wasps emerged which stung them and flew elusively away. The Persian effort failed, and it was reserved for the half-Greek, half-barbaric Macedonians, established in the root of the Greek Peninsula itself, to end the first cycle of sea-power by conquering to south of them the Greek sea-base, and then marching into Asia, and through Syria into Egypt, and on the way destroying Tyre of the Phœnicians. Thus they made a 'closed sea' of the Eastern Mediterranean by depriving both the Greeks and the Phœnicians of their bases. That done, the Macedonian King Alexander could advance light-heartedly into Upper Asia. We may talk of the mobility of ships and of the long arm of the fleet, but, after all, sea-power is fundamentally a matter of appropriate bases, productive and secure. Greek sea-power passed through the same phases as Egyptian river-power. The end of both was the same; without the protection of a navy commerce moved securely over a water-way because all the shores were held by one and the same land-power.

Now we go to the Western Mediterranean. Rome there began as a fortified town on a hill, at the foot of which was a bridge and a river-wharf. This hill-bridge-port-town was the citadel and market of a small nation of farmers, who tilled Latium, the 'broad land' or plain, between the Apennines and the sea. 'Father' Tiber was for shipping purposes merely a creek, navigable for the small seacraft of those days, which entered thus from the coast a few miles into the midst of the plain, but that was enough to give Rome the

Fig. 4.—Latium, a fertile sea-base.advantage over her rivals, the towns crowning the Alban and Etruscan hills of the neighbourhood. Rome had the bridge and the inmost port just as had London.

Based on the productivity of Latium, the Romans issued from the Tiber to traffic round the shores of the Western Mediterranean. Soon they came into competition with the Carthaginians, who were based on the fertility of the Mejerdeh valley in the opposite promontory of Africa. The First Punic or Phœnician War ensued, and the Romans victoriously held the sea. They then proceeded to widen their base by annexing all the peninsular part of Italy as far as the Rubicon River.

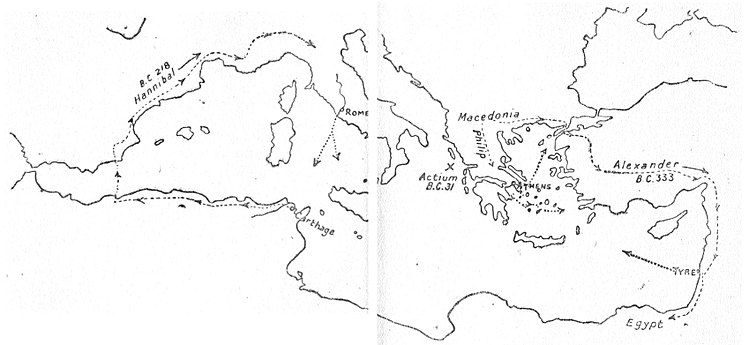

In the Second Punic War, the Carthaginian general, Hannibal, endeavoured to outflank the Roman sea-power by marching round it, as Xerxes and Alexander had done in regard the sea-powers opposed to them. He carried his army over the western narrows from Africa into Spain, and then advanced through Southern Gaul into Italy. He was defeated, and Rome annexed the Mediterranean coasts of Gaul and Spain. By taking Carthage itself in the Third Punic War, she made a 'closed sea' of the Western Mediterranean, for all the shores were held by one and the same land-power.

There remained the task of uniting the controls of the Western and Eastern basins of the Mediterranean, connected by the Sicilian Strait and the Strait of Messina. The Roman legions passed over into Macedonia and thence

Fig. 5.—Two famous marches for the purpose of outflanking sea-power; also a victory which 'closed' the Mediterranean.

When Rome had completed the organisation of her power round the Mediterranean, there followed a long transitional epoch, during which the oceanic development of Western civilisation was gradually preparing. The transition began with the Roman road system, constructed for the greater mobility of the marching legions. After the close of the Punic Wars four Latin-speaking provinces encircled the Western Mediterranean—Italy, Southern Gaul, Eastern and Southern Spain, and Carthaginian Africa. The outer boundary of the African province was protected by the Sahara Desert, and Italy had in rear the Adriatic moat, but in Gaul and Spain Rome found herself the uncomfortable neighbour of independent Celtic tribes. Thus the familiar dilemma of Empire presented itself; to advance and end the menace, or to entrench and shut it out, but leave it in being. A still virile people chose the former course, and the frontier and the roads were carried through to the ocean along a thousand miles of frontage between Cape St. Vincent and the mouths of the Rhine. As a consequence the Latin portion of the Empire came to be based on two features of Physical Geography: on the one hand was the Latin Sea—the Western Mediterranean; and on the other hand was the Latin Peninsula, between the Mediterranean and. the ocean.[2]

Julius Cæsar penetrated to the Bay of

Biscay, and built a fleet wherewith he defeated the fleet of the Veneti of Brittany. Then, because the Celts of Britain were giving help to their Gallic kinsmen, he crossed the Channel and smote them in their island base.

A hundred years later the Romans conquered all the lower and more fruitful portion of Britain, and so eliminated the risk of the rise of a sea-power off the Gallic coast. In this way the Channel also became a 'closed sea,' controlled by land-power.After four centuries the land-power of Rome waned, and the seas on either side of the Latin Peninsula then soon ceased to be 'closed.' The Norsemen raided over the North Sea from their fiords, and through the Channel, and through the Straits of Gibraltar, even into the recesses of the Mediterranean, enveloping with their sea-power the whole great peninsula. They seized forward bases in the islands of Britain and Sicily, and even nibbled at the mainland edges in Normandy and Southern Italy.

At the same time the Saracen camel-men came down from Arabia and took Carthage, Egypt, and Syria from the Empire—the provinces, that is to say, south of the Mediterranean. Then they launched their fleets on the water, and seized part of Sicily and part of Spain for overseas bases. Thus the Mediterranean ceased to be the arterial way of an Empire, and became the frontier moat dividing Christendom from Islam. But the greater sea-power of the Saracens enabled them to hold Spain, though north of the water, just as at an earlier time the greater sea-power of Rome had enabled her to hold Carthage, though south of the water.

For a thousand years Latin Christendom was thus imprisoned in the Latin Peninsula and its appendant island of Britain. Fifteen hundred miles north-eastward, measured in a straight line, trends the oceanic coast from the Sacred Promontory of the ancients to the Straits at Copenhagen, and fifteen hundred miles eastward, measured in the same way, lies the sinuous Mediterranean coast from the Sacred Promontory to the Straits at Constantinople. A lesser peninsula advances towards the main peninsula at each strait, Scandinavia on the one hand, and Asia Minor on the other; and behind the land bars so formed are two landgirt basins, the Baltic and Black Seas. If Britain be considered as balancing Italy, the symmetry of the distal end of the main peninsula is such that you might lay a Latin Cross upon it with the head in Germany, the arms in Britain and Italy, the feet in Spain, and the centre in France, thus typifying that ecclesiastical empire of the five nations which, though shifted northward, was the mediæval heir of the Roman Cæsars. Towards the East, however, where the Baltic and Black Seas first begin to define the peninsular character of Europe, the outline is less shapely, for the Balkan peninsula protrudes southward, only tapering finally into the historic little peninsula of Greece.

Is it not tempting to speculate on what might have happened had Rome not refused to conquer eastward of the Rhine? Who can say that a single mighty sea-power, wholly Latinised as far as the Black and Baltic Seas, would not have commanded the world from its peninsular base? But Classical Rome was primarily a Mediterranean and not a peninsular power, and the Rhine-Danube frontier must be regarded as demarking a penetration from the Mediterranean coast rather than as the incomplete achievement of a peninsular policy.

It was the 'opening' again of the seas on either hand which first compacted Europe in the peninsular sense. Reaction had to be organised, or the pressures from north and south would have obliterated Christendom. So Charlemagne erected an Empire astride of the Rhine, half Latin and half German by speech, but wholly Latin ecclesiastically. With this Empire as base the Crusades were afterwards undertaken. Seen in large perspective at this distance of time, and from the seaman's point of view, the Crusades, if successful, would have had for their main effect the 'closing' once more of the Mediterranean Sea. The long series of these wars, extending over two centuries, took two courses. On the one hand, fleets were sent out from

Fig. 8.—Showing Germany the neck of the Latin Peninsula, and Macedonia in the neck of the Greek Peninsula.

The peoples of the Latin civilisation were thus hardened by a winter o£ centuries, called the Dark Ages, during which they were besieged in their homeland by the Mohammedans, and failed to break out by their Crusading sorties. Only in the fifteenth century did Time ripen for the great adventure on the ocean which was to make the world European. It is worth pausing for a moment to consider further the unique environment in which the Western strain of our human breed developed the enterprise and tenacity which have given it the lead in the modern world. Europe is but a small corner of the great island which also contains Asia and Africa, but the cradle land of the Europeans was only a half of Europe—the Latin Peninsula and the subsidiary peninsulas and islands clustered around it. Broad deserts lay to the south, which could be crossed only in some three months on camel back, so that the black men were fended off from the white men. The trackless ocean lay to the west, and to the north the frozen ocean. To the north-east were interminable pine forests, and rivers flowing either to ice-choked mouths in the Arctic Sea or to inland waters, such as the Caspian Sea, detached from the ocean. Only to the south-east were there practicable oasis-routes leading to the outer world, but these were closed, more or less completely, from the seventh to the nineteenth century, by the Arabs and the Turks.

In any case, however, the European system of water-ways was detached by the Isthmus of Suez from the Indian Ocean. Therefore from the seaman's point of view Europe was a quite

Fig. 9.—The River and Coast Ways of the Seaman's Europe. The land surface of all Europe measures less than 2 per cent. of the surface of the Globe. This was the prison of mediæval Christendom, but the sea-base of modern Christendom.

There were two fortunate circumstances in regard to the mediæval siege of Europe. On the one hand, the Infidels had not command of inexhaustible man-power, for they were based on arid and sub-arid deserts and steppes, and on comparatively small oasis-lands; on the other hand, the Latin Peninsula was not seriously threatened along its oceanic border, for the Norsemen, though fierce and cruel while they remained Pagan, were based on fiord-valleys even less extensive and less fruitful than the oases, and wherever they settled—in England, Normandy, Sicily, or Russia—their small numbers were soon absorbed into the older populations. Thus the whole defensive strength of Europe could be thrown against the south-eastern danger. But as the European civilisation gained momentum, there was energy to spare upon the ocean frontage; Venice and Austria sufficed for the later struggle against the Turks.

After the essays, without practical result, of the Norsemen to force their way through the northern ice of Greenland, the Portuguese undertook to find a sea-way to the Indies round the coast of Africa. They were inspired to the venture by the lead of Prince Henry 'the Navigator,' half Englishman and half Portuguese. At first sight it seems strange that pilots like Columbus, who had spent their lives on coasting voyages, often going from Venice to Britain, should so long have delayed an exploration southward as they issued from the Straits of Gibraltar. Still more strange does it appear that when at last they had set themselves to discover the outline of Africa, it took them two generations of almost annual voyaging before Da Gama led the way into the Indian Ocean. The cause of their difficulties was physical. For a thousand miles, from the latitude of the Canary Islands to that of Cape Verde, the African coast is a torrid desert, because the dry trade wind there blows off the land without ceasing. It might be a relatively easy matter to sail southward on that steady breeze, but how was the voyage back to be accomplished by ships which could not sail near the wind like a modern chpper, and yet dared neither sail out on to the broad ocean across the wind, nor yet tediously tack their way home off a coast with no supplies of fresh food and water, in a time when the plague of scurvy had not yet been mastered?

Once the Portuguese had found the ocean-way into the Indian seas, they soon disposed of the opposition of the Arab dhows. Europe had taken its foes in rear; it had sailed round to the rear of the land, just as Xerxes, Alexander, Hannibal, and the Crusaders had marched round to the rear of the sea.

From that time until the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, the seamen of Europe continued in ever-increasing number to round the Cape, and to sail northward on the Eastern Ocean as far as China and Japan. Only one ship, the Vega of the Swedish Baron Nordenskiold, has to this day made the passage round the north of Asia—with infinite risk, and in two years—and she happens not to have circumnavigated the Triple Continent, for she returned home through the Suez Canal. Nor was the overland journey to the Indies undertaken, except as an adventure, until last century. The trade to the Indies was conducted by coasting—no doubt in a bold way, from point to point—round the great southward promontory whose shores were European and African on the one side, and African and Asiatic on the other. From

Fig. 10.—The world-promontory.the point of view of the traffic to the Indies, the world was a vast cape, standing out southward from between Britain and Japan. This world-promontory was enveloped by sea-power, and Latin promontories beforehand: all its coasts were open to ship-borne trade or to attack from the sea. The seamen naturally chose for the local bases of their trading or warfare small islands off the continental coast, such as Mombasa, Bombay, Singapore, and Hong-Kong, or small peninsulas, such as the Cape of Good Hope and Aden, since those positions offered shelter for their ships and security for their depots. When grown bolder and stronger, they put their commercial cities, such as Calcutta and Shanghai, near the entry of great river-ways into productive and populous market-lands. The seamen of Europe, owing to their greater mobility, have thus had superiority for some four centuries over the landsmen of Africa and Asia.

The passing of the imminent danger to Christendom, because of the relative weakening of Islam, was, no doubt, one of the reasons for the break-up of Mediæval Europe at the close of the Middle Ages; already in 1493 the Pope had to draw his famous line through the ocean, from Pole to Pole, in order to prevent Spanish and Portuguese seamen from quarrelling. As a result of this break-up, there arose five competing oceanic powers—Portuguese, Spanish, French, Dutch, and English—in the place of the one power which would, no doubt, have been the ideal of the Crusaders.

Thus the outcome of a thousand years of transition, from the ancient to the modern conditions of sea-power, is such as to prompt a comparison between the Greek and Latin Peninsulas, each with its off-set island. Peninsular Greece and insular Crete anticipated in their relations the Latin Peninsula and the island of Britain. Under the Dorians the greater resources of the peninsular mainland were utilised for the conquest of Crete, but at a later time the rivalry of Sparta and Athens prevented a full exploitation of the peninsula as a sea-base. So in the case of the greater peninsula and greater island, Britain was conquered and held by Rome from the peninsular mainland; but when the Middle Ages were closing, several rival sea-bases occupied the Latin Peninsula, each of them open to attack from the land behind, as Athens and Sparta had been open to the Macedonian invasion. Of these Latin sea-bases, one, Venice, fronted towards Islam, while the others contended with internecine feuds for the command of the ocean, so that in the end the lesser British insular base, faced by no united peninsular base, became the home of a power which enveloped and contained the greater peninsula.

Within Great Britain itself it is true that there was not effective unity until the eighteenth century, but the facts of physical geography have determined that there should always be a predominant English people in the south of the island, whether as foe or partner of the Scottish and Welsh peoples. From Norman days, until the growth of the modern industries upon the coal-fields, the English nation was almost uniquely simple in its structure. It is that which makes English history the epic story that it is until the histories of Scotland and Ireland come to confuse their currents with it. One fertile plain between the Mountains of the west and north and the Narrow Seas to the east and south, a people of farmers, a single king, a single parliament, a tidal river, a single great city for central market and port—those are the elements on which the England was built whose warning beacons blazed on the hill-tops from Plymouth to Berwick-on-Tweed, in that night of Elizabeth's reign when the Spanish Armada had entered the Channel. On a smaller scale, Latium, the Tiber, the City, the Senate, and the People of Rome once presented a similar unity and a similar executive strength. The real base historically of British sea-power was our English plain—fertile and detached; coal and iron from round the borders of the plain have been added in later times. The white ensign of the Royal Navy is with some historic justice the flag of St. George, with a 'difference' for the minor partners.

Every characteristic of sea-power may be studied in British history during the last three centuries, but the home-base, productive and secure, is the one thing essential to which all things else have been added. We are told that we should thank God daily forour Channel, but as I looked out over the glorious harvest of this English plain in this critical year 1918, it seemed to me that our thanksgiving as a seafaring people should be no less for our fruitful soil. Insular Crete had to yield to the Dorians from the greater peninsula.

Four times in the past three centuries was it attempted to overthrow British sea-power from frontages on the peninsular coast opposite—from Spain, from Holland, and twice from France. At last, after Trafalgar, British sea-power definitively enveloped the Latin Peninsula, having subsidiary bases at Gibraltar, Malta, and Heligoland. The continental coastline became the effective British boundary, notwithstanding the enemy privateers, and Britain could prepare war at her ease upon the sea. So she undertook the 'Peninsular' campaigns in Spain, and landed armies in the Netherlands in aid of her military allies. She even anticipated Gallipoli by bringing away her armies from Walcheren and Corunna.

When the Napoleonic War was over, British sea-power encompassed, almost without competition, that great world-promontory which stands forward to the Cape of Good Hope from between Britain and Japan. British merchant ships on the sea were a part of the British Empire; British capital ventured abroad in foreign countries was a part of British resources, controlled from the city of London and available for the maintenance of power on and over the seas. It was a proud and lucrative position, and seemed so secure that the mid-Victorian folk thought it almost in the natural order of things that insular Britain should rule the seas. We were, perhaps, not quite a popular people in the rest of the world; our position behind a Channel seemed an unfair advantage. But warships cannot navigate the mountains, and since the French wars of the Plantagenets we have not sought to make permanent European conquests, so that, on the whole, we may hope that the verdict of foreign historians on our Britain of the nineteenth century may resemble that of the famous schoolboy who described his headmaster as 'a beast, but a just beast.'

Perhaps the most remarkable outcome of British sea-power was the position in the Indian Ocean during the generation before the War. The British 'Raj' in India depended on support from the sea, yet on all the waters between the Cape of Good Hope, India, and Australia, there was habitually no British battle-ship or even first-class cruiser. In effect, the Indian Ocean was a 'closed sea.' Britain owned or 'protected' most of the coast lines, and the remaining frontages were either on islands, as the Dutch East Indies, or on territories such as Portuguese Mozambique and German East Africa, which, although continental, were inaccessible under existing conditions by land-way from Europe. Save in the Persian Gulf, there could be no rival base for sea-power which combined security with the needful resources, and Britain made it a declared principle of her policy that no sea-base should be established on either the Persian or Turkish shores of the Persian Gulf. Superficially there is a striking similarity between the closed Mediterranean of the Romans, with the legions along the Rhine frontier, and the closed Indian Ocean, with the British Army on the North-West Frontier of India. The difference lay in the fact that, whereas the closing of the Mediterranean depended on the Legions, the closing of the Indian Seas was maintained by the long arm of sea-power itself from the Home base.

In the foregoing rapid survey of the vicissitudes of sea-power, we have not stayed to consider that well-worn theme of the single mastery of the seas. Every one now realises that owing to the continuity of the ocean and the mobility of ships, a decisive battle at sea has immediate and far-reaching results. Cæsar beat Antony at Actium, and Cæsar's orders were enforceable forthwith on every shore of the Mediterranean. Britain won her culminating victory at Trafalgar, and could deny all the ocean to the fleets of her enemies, could transport her armies to whatsoever coast she would and remove them again, could carry supplies home from foreign sources, and could exert pressure in negotiation on whatsoever offending State had a sea-front. Our concern here has been rather in regard to the bases of sea-power and the relation to these of land-power. In the long run, that is the fundamental question. There were fleets of war canoes on the Nile, and the Nile was closed to their contention by a single land-power controlling their fertile bases through all the length of Egypt. A Cretan insular base was conquered from a larger Greek peninsular base. Macedonian land-power closed the Eastern Mediterranean to the warships both of Greeks and Phœnicians by depriving them impartially of their bases. Hannibal struck overland at the peninsular base of Roman sea-power, and that base was saved by victory on land. Cæsar won the mastery of the Mediterranean by victory on the water, and Rome then retained control of it by the defence of land frontiers. In the Middle Ages Latin Christendom defended itself on the sea from its peninsular base, but in modern times, because competing States grew up within that peninsula, and there were several bases of sea-power upon it, all open to attack from the land, the mastery of the seas passed to a power which was less broadly based, but on an island—fortunately a fertile and coal-bearing island. On sea-power, thus based, British adventurers have founded an overseas Empire of colonies, plantations, depots, and protectorates, and have established, by means of sea-borne armies, local land-powers in India and Egypt. So impressive have been the results of British sea-power that there has perhaps been a tendency to neglect the warnings of history and to regard sea-power in general as inevitably having, because of the unity of the ocean, the last word in the rivalry with land-power.

Never has sea-power played a greater part than in the recent War and in the events which led up to it. Those events began some twenty years ago with three great victories won by the British fleet without the firing of a gun. The first was at Manila, in the Pacific Ocean, when a German squadron threatened to intervene to protect a Spanish squadron, which was being defeated by an American squadron, and a British squadron stood by the Americans. Without unduly stressing that single incident, it may be taken as typical of the relations of the Powers during the war between Spain and America, which war gave to America detached possessions both in the Atlantic and Pacific, and led to her undertaking the construction of the Panama Canal, in order to gain the advantages of insularity for the mobilisation of her warships. So was a first step taken towards the reconciliation of British and American hearts. Moreover the Monroe doctrine was upheld in regard to South America.

The second of these victories of the British fleet was when it held the ocean during the South African War, of such vital consequence to the maintenance of the British rule in India; and the third was when it kept the ring round the Russo-Japanese War, and incidentally kept the door open into China. In all three cases history would have been very different but for the intervention of the British fleet. None the less—and perhaps as a consequence—the growth of the German fleet imder the successive Navy Laws, induced the withdrawal of the British battle squadrons from the Far East and from the Mediterranean, and co-operation in those seas with the Japanese and French sea-powers.

The Great War itself began in the old style, and it was not until 1917 that the new aspects of Reality became evident. In the very first days of the struggle the British fleet had already taken command of the ocean, enveloping, with the assistance of the French fleet, the whole peninsular theatre of the war on land. The German troops in the German Colonies were isolated, German merchant shipping was driven off the seas, the British expeditionary force was transported across the Channel without the loss of a man or a horse, and British and French supplies from over the ocean were safely brought in. In a word, the territories of Britain and France were made one for the purpose of the war, and their joint boundary was advanced to within gunshot range of the German coast—no small offset for the temporary, though deeply regretted, loss of certain French departments. After the battle of the Marne the true war-map of Europe would have shown a Franco-British frontier following the Norwegian, Danish, German, Dutch, and Belgian coasts—at a distance of three miles in the case of the neutral coasts—and then running as a sinuous line through Belgium and France to the Jura border of Switzerland. West of that boundary, whether by land or sea, the two Powers could make ready their defence against the enemy. Nine months later Italy dared to join the Allies, mainly because her ports were kept open by the Allied sea-power.

On the Eastern front also the old style of war held. Land-power was there divided into two contending forces, and the outer of the two, notwithstanding its incongruous Czardom, was allied with the sea-power of the Democratic West. In short, the disposition of forces repeated in a general way that of a century earlier, when British sea-power supported the Portuguese and Spaniards in 'the Peninsula,' and was allied with the autocracies of the Eastern land-powers. Napoleon fought on two fronts, which in the terms of to-day we should describe as Western and Eastern.

In 1917, however, came a great change, due to the entry of the United States into the War, the fall of the Russian Czardom, and the subsequent collapse of the Russian fighting strength. The world-strategy of the contest was entirely altered. We have been fighting since, and can afford to say it without hurting any of our allies, to make the world a safe place for democracies. So much as regards Idealism. But it is equally important that we should bear in mind the new face of Reality. We have been fighting lately, in the close of the War, a straight duel between land-power and sea-power, and sea-power has been laying siege to land-power. We have conquered, but had Germany conquered she would have established her sea-power on a wider base than any in history, and in fact on the widest possible base. The joint continent of Europe, Asia, and Africa, is now effectively, and not merely theoretically, an island. Now and again, lest we forget, let us call it the World-Island in what follows.

One reason why the seamen did not long ago rise to the generalisation implied in the expression 'World-Island,' is that they could not make the round voyage of it. An ice-cap, two thousand miles across, floats on the Polar Sea, with one edge aground on the shoals off the north of Asia. For the common purposes of navigation, therefore, the continent is not an island. The seamen of the last four centuries have treated it as a vast promontory stretching southward from a vague north, as a mountain peak may rise out of the clouds from hidden foundations. Even in the last century, since the opening of the Suez Canal, the eastward voyage has still been round a promontory, though with the point at Singapore instead of Cape Town.

This fact and its vastness have made men think of the Continent as though it differed from other islands in more than size. We speak of its parts as Europe, Asia, and Africa in precisely the same way that we speak of the parts of the ocean as Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian. In theory even the ancient Greeks regarded it as insular, yet they spoke of it as the 'World.' The school-children of to-day are taught of it as the 'Old World,' in contrast with a certain pair of peninsulas which together constitute the 'New World.' Seamen speak of it merely as 'the Continent,' the continuous land.

Let us consider for a moment the proportions and relations of this newly realised Great Island.[3] It is set as it were on the shoulder of the earth with reference to the North Pole. Measuring from Pole to Pole along the central meridian of Asia, we have first a thousand miles of ice-clad sea as far as the northern shore of Siberia, then five thousand miles of land to the southern point of India, and then seven thousand miles of sea to the Antarctic cap of ice-clad land. But measured along the meridian of the Bay of Bengal or of the Arabian Sea, Asia is only some three thousand five hundred miles across. From Paris to Vladivostok is six thousand miles, and from Paris to the Cape of Good Hope is a similar distance; but these measurements are on a Globe twenty-six thousand miles round. Were it not for the ice impediment to its circumnavigation, practical seamen would long ago have spoken of the Great Island by some such name, for it is only a little more than one-fifth as large as their ocean.

The World-Island ends in points north-eastward and south-eastward. On a clear day you can see from the north-eastern headland across Behring Strait to the beginning of the long pair of peninsulas, each measuring about one twenty-sixth of the Globe, which we call the Americas. Superficially there is no doubt a certain resemblance of symmetry in the Old and New Worlds; each consists of two peninsulas, Africa and Euro-Asia in the one case, and North and South America in the other. But there is no real likeness between them. The northern and north-eastern shores of Africa for nearly four thousand miles are so intimately related with the opposite shores of Europe and Asia that the Sahara constitutes a far more effective break in social continuity than does the Mediterranean. In the days of air navigation which are coming, sea-power will use the water-way of the Mediterranean and Red Seas only by the sufferance of land-power, for air-power is chiefly an arm of land-power, a new amphibious cavalry,, when the contest with sea-power is in question.

But North and South America, slenderly connected at Panama, are for practical purposes insular rather than peninsular in regard to one another. South America lies not merely to south, but also in the main to east of North America; the two lands are in echelon, as soldiers would say, and thus the broad ocean encircles South America, except for a minute proportion of its outline. A like fact is true of North America with reference to Asia, for it stretches out into the ocean from Behring Strait so that, as may be seen upon a globe, the shortest way from Pekin to New York is across Behring Strait, a circumstance which may some day have importance for the traveller by railway or air. The third of the new continents, Australia, lies a thousand miles from the south-eastern point of Asia, and measures only one sixty-fifth of the surface of the Globe.

Thus the three so-called new continents are in point of area merely satellites of the old continent. There is one ocean covering nine-twelfths of the Globe; there is one continent—the World-Island—covering two-twelfths of the Globe; and there are many smaller islands, whereof North America and South America are for effective purposes two, which together cover the remaining one-twelfth. The term 'New World' implies, now that we can see the Realities and not merely historic appearances, a wrong perspective.

The truth, seen with a broad vision, is that in the great World-Promontory, extending southward to the Cape of Good Hope, and in the North American sea-base we have, on a vast scale, yet a third contrast of peninsula and island to be set beside the Greek peninsula and the island of Crete, and the Latin Peninsula and the British Island. But there is this vital difference, that the World-Promontory, when united by modern overland communications, is in fact the World-Island, possessed potentially of the advantages both of insularity and of incomparably great resources.

Leading Americans have for some time appreciated the fact that their country is no longer a world apart, and President Wilson had brought his whole people round to that view when they consented to throw themselves into the War. But North America is no longer even a continent; in this twentieth century it is shrinking to be an island. Americans used to think of their three millions of square miles as the equivalent of all Europe; some day, they said, there would be a United States of Europe as sister to the United States of America. Now, though they may not all have realised it, they must no longer think of, Europe apart from Asia and Africa. The Old World has become insular, or in other words a unit, incomparably the largest geographical unit on our Globe.There is a remarkable parallelism between the short history of America and the longer history of England; both countries have now passed through the same succession of Colonial, Continental, and Insular stages. The Angle and Saxon settlements along the east and south coast of Britain have often been regarded as anticipating the thirteen English Colonies along the east coast of North America; what has not always been remembered is that there was a continental stage in English history to be compared with that of Lincoln in America. The wars of Alfred the Great and William the Conqueror were in no small degree between contending parts of England, with the Norsemen intervening, and England was not effectively insular until the time of Elizabeth, because not until then was she free from the hostility of Scotland, and herself united, and therefore a unit, in her relations with the neighbouring continent. America is to-day a unit, for the American people have fought out their internal differences, and it is insular, because events are compelling Americans to realise that their so-called continent lies on the same globe as the Continent.

Picture upon the map of the world this War as it has been fought in the year 1918. It has been a war between Islanders and Continentals, there can be no doubt of that. It has been fought on the Continent, chiefly across the landward front of peninsular France; and ranged on the one side have been Britain, Canada, the United States, Brazil, Australia, New Zealand, and Japan—all insular. France and Italy are peninsular, but even with that advantage they would not have been in the War to the end had it not been for the support of the Islanders. India and China—so far as China has been in the War on the Manchurian front—may be regarded as advanced guards of British, American, and Japanese sea-power. Dutch Java is the only island of large population which is not in the Western Alliance, and even Java is not on the side of the Continentals. There can be no mistaking the significance of this unanimity of the Islanders. The collapse of Russia has cleared our view of the realities, as the Russian revolution purified the ideals for which we have been fighting.

The facts appear in the same perspective if we consider the population of the Globe. More than fourteen-sixteenths of all humanity live on the Great Continent, and nearly one-sixteenth more on the closely off-set Islands of Britain and Japan. Even to-day, after four centuries of emigration, only about one-sixteenth live in the lesser continents. Nor is time likely to change these proportions materially. If the middle-west of North America comes presently to support, let us say, another hundred million people, it is probable that the interior of Asia will at the same time carry two hundred millions more than now, and if the Tropical part of South America should feed a hundred millions more, then the Tropical parts of Africa and the Indies may not improbably support two hundred millions more. The Congo Forest alone, subdued to agriculture, would maintain some four hundred million souls if populated with the same density as Java, and the Javanese population is still growing. Have we any right, moreover, to assume that, given its climate and history, the interior of Asia would not nourish a population as virile as that of Europe, North America, or Japan?What if the Great Continent, the whole World-Island or a large part of it, were at some future time to become a single and united base of sea-power? Would not the other insular bases be outbuilt as regards ships and outmanned as regards seamen? Their fleets would no doubt fight with all the heroism begotten of their histories, but the end would be fated. Even in the present War, insular America has had to come to the aid of insular Britain, not because the British fleet could not have held the seas for the time being, but lest such a building and manning base were to be assured to Germany at the Peace, or rather Truce, that Britain would inevitably be outbuilt and outmanned a few years later.

The surrender of the German fleet in the Firth of Forth is a dazzling event, but in all soberness, if we would take the long view, must we not still reckon with the possibility that a large part of the Great Continent might some day be united under a single sway, and that an invincible sea-power might be based upon it? May we not have headed off that danger in this War, and yet leave by our settlement the opening for a fresh attempt in the future? Ought we not to recognise that that is the great ultimate threat to the World's liberty so far as strategy is concerned, and to provide against it in our new political system?

Let us look at the matter from the Landsman's point of view.

- ↑ See The Dawn of History, by Professor J. L. Myres.

- ↑ I do not know whether these names, Latin Sea and Latin Peninsula, have been used beforehand. It seems to me that they serve to crystallise important generalisations, and I propose using them henceforth.

- ↑ It would be misleading to attempt to represent the statements which follow in map form. They can only be appreciated on a globe. Therefore they are illustrated by diagrams; see Figs. 12 and 13.