Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology/Antonius 14.

14. L. Antonius M. f. M. n., the younger brother of the preceding and of the triumvir, was tribune of the plebs in 44, and upon Caesar's death took an active part in supporting his brother's interests, especially by introducing au agrarian law to conciliate the people and Caesar's veteran troops. He subsequently accompanied his brother into Gaul, and obtained the consulship for 41, in which year he triumphed on account of some successes he had gained over the Alpine tribes. During his consulship a dispute arose between him and Caesar about the division of the lands among the veterans, which finally led to a war between them, commonly called the Perusinian war. Lucius engaged in this war chiefly at the instigation of Fulvia, his brother's wife, who had great political influence at Rome. At first, Lucius obtained possession of Rome during the absence of Caesar ; but on the approach of the latter, he retired northwards to Perusia, where he was straightway closely besieged. Famine compelled him to surrender the town to Caesar in the following year (40). His life was spared, and he was shortly afterwards appointed by Caesar to the command of Iberia, from which time we hear no more of him.

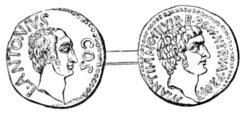

L. Antonius took the surname of Pietas (Dion Cass, xlviii. 5), because he pretended to attack Caesar in order to support his brother's interests. It is true, that when he obtained possession of Rome in his consulship, he proposed the abolition of the triumvirate ; but this does not prove, as some modern writers would have it, that he was opposed to his brother's interests. Cicero draws a frightful picture of Lucius' character. He calls him a gladiator and a robber, and heaps upon him every term of reproach and contempt. (Phil. iii. 12, V. 7, 1 1, xii. 8, &c.) Much of this is of course exaggeration. (Orelli, Onomast.; Drumann's Gesch. Roms, i. p. 527, &c.) The annexed coin of L. AnAntonius represents also the head of his brother, M. Antonius, the triumvir, with the inscription: M. Ant. Im(p). Avg. IIIvir. R. P. C. M. Nerva. Proq. P.

15. 16. Antonia. [Antonia, 2. 3.]

17. Antonia, the daughter of M. Antonius, the triumvir, and Antonia. [Antonia, 4.]

18. M. Antonius, M. f. M. n., called by the Greek writers Antyllus (Ἄντυλλοϛ), which is probably only a corrupt form for Antonillus (young Antonius), was the elder of the two sons of the triumvir by his wife Fulvia. In B.C. 36, while he was still a child, he was betrothed to Julia, the daughter of Caesar Octavianus. After the battle of Actium, when Antony despaired of success at Alexandria, he conferred upon his son Marcus the toga virilis (B.C. 30), that he might be able to take his place in case of his death. He sent him with proposals of peace to Caesar, which were rejected; and on his death, shortly after, young Marcus was executed by order of Caesar. (Dion Cass, xlviii. 54, li. 6, 8, 15; Suet. Aug. 17, 63 ; Plut. Ant. 71, 81, 87.)

19. Julus Antonius, M. f. M. n., the younger son of the triumvir by Fulvia, was brought up by his step-mother Octavia at Rome, and after his father's death (B.C. 30) received great marks of favour from Augustus, through the influence of Octavia. (Plut. Ant. 87; Dion Cass. li. 15.) Augustus married him to Marcella, the daughter of Octavia by her first husband, C. Marcellus, conferred upon him the praetorship in B.C. 13, and the consulship in B.C. 10. (Vell. Pat. ii. 100; Dion Cass. liv. 26, 36; Suet. Claud. 2.) In consequence of his adulterous intercourse with Julia, the daughter of Augustus, he was condemned to death by the emperor in B.C. 2, but seems to have anticipated his execution by a voluntary death. He was also accused of aiming at the empire. (Dion Cass. lv. 10; Senec. de Brevit. Vit. 5 ; Tac. Ann. iv. 44, iii. 18; Plin. H. N. vii. 46; Vell. Pat. l. c.) Antonius was a poet, as we learn from one of Horace's odes (iv. 2), which is addressed to him.

20. Antonia Major, the elder daughter of M. Antonius and Octavia. [Antonia, No. 5.]

21. Antonia Minor, the younger daughter of M. Antonius and Octavia. [Antonia, No. 6.]

22. Alexander, son of M. Antonius and Cleopatra. [Alexander, p. 112, a.]

23. Cleopatra, daughter of M. Antonius and Cleopatra. [Cleopatra.]

24. Ptolemaeus Philadelphus, son of M. Antonius and Cleopatra. [Ptolemaeus.]

25. L. Antonius, son of No. 19 and Marcella, and grandson of the triumvir, was sent, after his father's death, into honourable exile at Massilia, where he died in A.D. 25. (Tac. Ann. iv. 44.)

ANTO'NIUS (Ἀντώνιοϛ). 1. Of Argos, a Greek poet, one of whose epigrams is still extant in the Greek Anthology, (ix. 102; comp. Jacobs, ad Anthol. vol. xiii. p. 852.)

2. Surnamed Melissa (the Bee), a Greek monk, who is placed by some writers in the eighth and by others in the twelfth century of our era. He must, however, at any rate have lived after the time of Theophylact, whom he mentions. He made a collection of so-called loci communes, or sentences on virtues and vices, which is still extant. It resembles the Sermones of Stobaeus, and consists of two books in 176 titles. The extracts are taken from the early Christian fathers. The work is printed at the end of the editions of Stobaeus published at Frankfort, 1581, and Geneva, 1609, fol. It is also contained in the Biblioth. Patr. vol. v. p. 878, &c., ed. Paris. (Fabr. Bibl. Gr. ix. p. 744, &c.; Cave, Script. Eccles. Hist. Lit. i. p. 666, ed. London.)

3. A Greek monk, and a disciple of Simeon

Stylites, lived about a. d. 460. He wrote a life

of his master Simeon, with whom he had lived

on intimate terms. It was written in Greek, and

L. AUatius {Diatr. de Script. Siin. p. 8) attests,

that he saw a Greek MS. of it; but the only

edition which has been published is a Latin

translation in Roland's ^d. Sandor. i. p. 264. (Cave,

Script. Eccles. Hist. Lit. ii. p. 145.) Vossius {De

Hist. Lai. p. 231), who knew only the Latin translation, was doubtful whether he should consider

Antonius as a Latin or a Greek historian.

4. ST., sometimes surnamed Abbas, because

he is believed to have been the founder of the

monastic life among the early Christians, was

bom in a. d. 251, at Coma, near Heracleia, in

Middle Egypt. His earliest years were spent in

seclusion, and the Greek language, which then

every pergon of education used to acquire, remained unknown to him. He merely spoke and wrote

the Egyptian language. At the age of nineteen,

after having lost both his parents, he distributed

his large property among his neighbours and the

poor, and determined to live in solitary seclusion

in the neighbourhood of his birthplace. The

struggle before he fully overcame the desires of the

flesh is said to have been immense ; but at length

he succeeded, and the simple diet which he

adopted, combined with manual labour, strength-

ened his health so much, that he lived to the age

of 105 years. In a. d. 285 he withdrew to the

mountains of eastern Egypt, where he took up his

abode in a decayed castle or tower. Here he spent

twenty years in solitude, and in constant stnlggles

with the evil spirit. It was not till A. D. 305, that

his friends prevailed upon him to return to the

world. He now began his active and public career.

A number of disciples gathered around him, and his

preaching, together with the many miraculous cures

he was said to perform on the sick, spread his fame

all over Egj-pt. The number of persons anxious to

learn from him and to follow his mode of life increased every year. Of such persons he made two

settlements, one in the mountains of eastern Egypt,

and another near the town of Arsinoe, and he himself usually spent his time in one of these monasteries, if we may call them so. From the accounts

of St. Athanasius in his life of Antonius, it is clear

that most of the essential points of a monastic life

were observed in these establishments. During

the persecution of the Christians in the reign of the

emperor Maximian, A. D. 311, Antonius, anxious

to gain the palm of a martyr, went to Alexandria,

but all his efforts and his opposition to the commands of the government were of no avail, and he