Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology/Sulla 5.

5. L. Cornelius Sulla Felix, the dictator, was born in b. c. 138. Like most other great men, he was the architect of his own fortunes. He possessed neither of the two great advantages which secured for the Roman nobles easy access to the honours of the commonwealth, an illustrious ancestry and hereditary wealth. His father had left him so small a property that he paid for his lodgings very little more than a freedman who lived in the same house with him. But still his means were sufficient to secure for him a good

STEMMA SULLARUM

| 1. P. Cornelius (Rufinus) Sulla, pr. b. c. 212. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. P. Cornelius Sulla, pr. b. c. 186. | 3. Ser. Cornelius Sulla, leg. b. c. 167. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. L. Cornelius Sulla. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. L. Cornelius Sulla Felix, Dictator. | 8. Serv. Cornelius Sulla. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. Cornelia Sulla. | Cornelia, married Q. Pompeius Rufus. [Cornelia, No. 8.] | 7. Faustus Cornelius Sulla, m. Pompeia. | Fausta, m. 1. C. Memmius. [Fausta.] | Postuma, born after the death of the Dictator. | 9. P. Cornelius Sulla, cos. desig. b.c. 66. | 10. Serv. Cornelius Sulla | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 11. P. Cornelius Sulla. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. L. Cornelius Sulla, cos. b. c. 5. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 13. L. Cornelius Sulla Felix, cos. a. d. 33. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 14. L. Cornelius Sulla, cos. suff. a. d. 52. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Faustus Cornelius Sulla, cos. a. d. 52. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16. Cornelius Sulla, praef. Cappadocia sub Elagabalo. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

education. He studied the Greek and Roman literature with diligence and success, and appears early to have imbibed that love for literature and art by which he was distinguished throughout his life. At the same time that he was cultivating his mind, he was also indulging his senses. He passed a great part of his time in the company of actors and actresses; he was fond of wine and women; and he continued to pursue his pleasures with as much eagerness as his ambitious schemes down to the time of his death. He possessed all the accomplishments and all the vices which the old Cato had been most accustomed to denounce, and he was one of those patterns of Greek literature and of Greek profligacy who had begun to make their appearance at Rome in Cato's time, and had since become more and more common among the Roman nobles. But Sulla's love of pleasure did not absorb all his time, nor did it emasculate his mind; for no Roman during the latter days of the republic, with the exception of Julius Caesar, had a clearer judgment, a keener discrimination of character, or a firmer will. The truth of this the following history will abundantly prove.

The slender property of Sulla was increased by the liberality of his step-mother and of a courtezan named Nicopolis, both of whom left him all their fortune. His means, though still scanty for a Roman noble, now enabled him to aspire to the honours of the state, and he accordingly became a candidate for the quaestorship, to which he was elected for the year b. c. 107. He was ordered to carry over the cavalry to the consul C. Marius, who had just taken the command of the Jugurthine war in Africa. Marius was not well pleased that a quaestor had been assigned to him, who was only known for his profligacy, and who had had no experience in war; but the zeal and energy with which Sulla attended to his new duties soon rendered him a useful and skilful officer, and gained for him the unqualified approbation of his commander, notwithstanding his previous prejudices against him. He was equally successful in winning the affections of the soldiers. He always addressed them with the greatest kindness, seized every opportunity of conferring favours upon them, was ever ready to take part in all the jests of the camp, and at the same time never shrunk from sharing in all their labours and dangers. Sulla, doubtless, had already the consulship before his eyes, and thus early did he show that he possessed the great secret of a man's success in a free state, the art of winning the affections of his fellow-men. He distinguished himself at the battle of Cirta, in which Jugurtha and Bocchus were defeated; and when the latter entered into negotiations with Marius, for the purpose of delivering the Numidian king into the hands of the Romans, the consul sent Sulla to Bocchus to bring the matter to a conclusion. It was chiefly owing to the influence which Sulla had acquired over the mind of Bocchus, that the latter, after much hesitation, was eventually persuaded to sacrifice his ally. Sulla carried Jugurtha in chains to the camp of Marius. [Jugurtha.] The quaestor shared with the consul the glory of bringing this war to a conclusion; and Sulla himself was so proud of his share in the success, that he had a seal ring engraved, representing the surrender of Jugurtha, which he continued to wear till the day of his death.

Italy was now threatened with an invasion by the vast hordes of the Cimbri and Teutones, who had already destroyed several Roman armies. Marius was accordingly again raised to the consulship, which he held for four years in succession, b. c. 104—101. In the first of these years Sulla served under Marius as legate, and in the second as tribunus militum, and in each year gained great distinction by his military services. But towards the end of b. c. 103, or the beginning of b. c. 102, the good understanding which had hitherto prevailed between Marius and Sulla was interrupted, the former being jealous, says Plutarch, of the rising fame of his officer. Sulla accordingly left Marius in b. c. 102, in order to serve under his colleague Q. Catulus, with whom he had still greater opportunities of gaining distinction, as Catulus was not much of a general, and was therefore willing to entrust the chief management of the war to Sulla. The latter reduced several Alpine tribes to subjection, and took such good care to keep his troops supplied with provisions, that on one occasion he was able to relieve the army of Marius as well as his own, a circumstance which, as Sulla said in his memoirs, greatly annoyed Marius. Sulla fought in the decisive battle, by which the barbarians were destroyed in b. c. 101. [Catulus, No. 3; Marius, p. 956.]

Sulla now returned to Rome, and appears to have lived quietly for some years without taking any part in public affairs. He became a candidate for the praetorship for the year b. c. 94, but failed. According to his own statement he lost his election because the people were disappointed at his not having previously offered himself for the aedileship, since they had been looking forward to a splendid exhibition of African wild beasts in the aedilician games of the friend of Bocchus. In the following year, however, he was more successful. He distributed money among the people with a liberal hand, and thus gained the praetorship for b. c. 93. In this office he gratified the wishes of the people by exhibiting in the Ludi Apollinares a hundred African lions, who were put to death in the circus by archers whom Bocchus had sent for the purpose.

In the following year, b. c. 92, Sulla was sent as propraetor into Cilicia, and was especially commissioned by the senate to restore Ariobarzanes to his kingdom of Cappadocia, from which he had been expelled by Mithridates. Although Sulla had not the command of a large force, he met with complete success. He defeated Gordius, the general of Mithridates in Cappadocia, and placed Ariobarzanes again on the throne. His success attracted the attention of Arsaces, king of Parthia, who accordingly sent an embassy to him to solicit the alliance of the Roman people. Sulla was the first Roman general who had any official intercourse with the Parthians, and he received the ambassadors with the same pride and arrogance as the Roman generals were accustomed to exhibit to the representatives of all foreign powers. Soon after this interview Sulla returned to Rome, where he was threatened in b. c. 91 by C. Censorinus with an impeachment for malversation, but the accusation was dropped.

The enmity between Marius and Sulla now assumed a more deadly form. Sulla's ability and increasing reputation had already led the aristocratical party to look up to him as one of their leaders, and thus political animosity was added to private hatred. In addition to this Marius and Sulla were both anxious to obtain the command of the impending war against Mithridates; and the success which attended Sulla's recent operations in the East had increased his popularity, and pointed him out as the most suitable person for this important command. About this time Bocchus erected in the Capitol gilded figures, representing the surrender of Jugurtha to Sulla, at which Marius was so enraged that he could scarcely be prevented from removing them by force. The exasperation of both parties became so violent that they nearly had recourse to arms against each other; but the breaking out of the Social War, and the immediate danger to which Rome was now exposed, hushed all private quarrels, and made all parties fight alike for their own preservation and that of the republic. Never had Rome greater need of the services of all her generals, and Marius and Sulla both took an active part in the war against the common foe. But Marius was now advanced in years, and did not possess the same activity either of mind or body as his younger rival. He had therefore the deep mortification of finding that his achievements were thrown into the shade by the superior energy of his former quaestor, and that his fortune paled more and more before the rising sum. In b. c. 90 Sulla served as legate under the consul L. Caesar, but his most brilliant exploits were performed in the following year, when he was legate of the consul L. Cato. In this year he destroyed the Campanian town of Stabiae, defeated L. Cluentius near Pompeii, and reduced the Hirpini to submission. He next penetrated into the very heart of Samnium, defeated Papius Mutilus, the leader of the Samnites, and followed up his victory by the capture of Bovianum, the chief town of this people. While he thus earned glory by his enterprises against the enemy, he was equally successful in gaining the affections of his troops. He pardoned their excesses, and connived at their crimes; and even when they put to death Albinus, one of his legates and a man of praetorian rank, he passed over the offence with the remark that his soldiers would fight all the better, and atone for their fault by their courage. As the time for the consular comitia approached Sulla hastened to Rome, where he was elected, almost unanimously, consul for the year b. c. 88, with Q. Pompeius Rufus as his colleague.

The war against Mithridates had now become inevitable, and the Social War was not yet brought to a conclusion. The senate assigned to Sulla the command of the former, and to his colleague Pompeius the conduct of the latter. Marius, however, would not resign without a struggle to his hated rival the distinction which he had so long coveted; but before he could venture to wrest from Sulla the authority with which he had been entrusted by the senate, he felt it necessary to strengthen the popular party. This he resolved to effect by identifying his interests with those of the Italian allies, who had lately obtained the franchise. He found a ready instrument for his purpose in the tribune P. Sulpicius Rufus, a man of ability and energy, but overwhelmed with debt, and who hoped that the spoils of the Mithridatic war, of which Marius promised him a liberal share, would relieve him from his embarrassments. This tribune accordingly brought forward two rogations, one to recal from exile those persons who had been banished in accordance with the Lex Varia, on account of their having been accessory to the Marsic war, and another, by which the Italians, who had just obtained the franchise, were to be distributed among the thirty-five tribes. The Italians, when they were admitted to the citizenship, were formed into eight or ten new tribes, which were to vote after the thirty-five old ones, and by this arrangement they would rarely be called upon to exercise their newly-acquired rights. On the other hand, the proposal of Sulpicius would place the whole political power in their hands, as they far outnumbered the old Roman citizens, and would thus have an overwhelming majority in each tribe. If this proposition passed into a lex, it was evident that the new citizens out of gratitude would confer upon Marius the command of the Mithridatic war. To prevent the tribune from putting these rogations to the vote, the consuls declared a justitium, during which no business could be legally transacted. But Sulpicius was resolved to carry his point; with an armed band of followers he entered the forum and called upon the consuls to withdraw the justitium; and upon their refusal to comply with his demand, he ordered his satellites to draw their swords and fall upon the consuls. Pompeius escaped, but his son Quintus, who was also the son-in-law of Sulla, was killed. Sulla himself only escaped by taking refuge in the house of Marius, which was close to the forum, and in order to save his life he was obliged to remove the justitium.

Sulla quitted Rome and hastened to his army, which was besieging Nola. The city was now in the hands of Sulpicius and Marius, and the two rogations passed into laws without opposition, as well as a third, conferring upon Marius the command of the Mithridatic war. Marius lost no time in sending some tribunes to assume on his behalf the command of the army at Nola; but the soldiers, who loved Sulla, and who feared that Marius might lead another army to Asia, and thus deprive them of their anticipated plunder, stoned his deputies to death. Sulla found his soldiers ready to respond to his wishes; they called upon him to lead them to Rome, and deliver the city from the tyrants. He was moreover encouraged by favourable omens and dreams, to which he always attached great importance. He therefore hesitated no longer, but at the head of six legions broke up from his encampment at Nola, and marched towards the city. His officers, however, refused to serve against their country, and all quitted him with the exception of one quaestor. This was the first time that a Roman had ever marched at the head of Roman troops against the city. Marius was taken by surprise. Such was the reverence that the Romans entertained for law, that it seems never to have occurred to him or to his party that Sulla would venture to draw his sword against the state. Marius attempted to gain time for preparations by forbidding Sulla in the name of the state to advance any further. But the praetors who carried this command narrowly escaped being murdered by the soldiers; and Marius as a last resort offered liberty to the slaves who would join him. But it was all in vain. Sulla entered the city without much difficulty, and Marius took to flight with his son and a few followers. Sulla used his victory with moderation. He protected the city from plunder, and in order to restrain his troops he passed the night in the streets along with his colleague. Only Marius, Sulpicius, and ten others of his bitterest enemies were declared public enemies by the senate at his command, on the ground of their having disturbed the public peace, taken up arms against the consuls, and excited the slaves to freedom. Sulpicius was betrayed by one of his slaves and put to death ; Marius and his son succeeded in escaping to Africa. [Marius, p. 957, b.]

Although Sulla had conquered Rome, he had neither the time, nor perhaps the power, to carry into execution any great organic changes in the constitution. His soldiers were impatient for the plunder of Asia; and he probably thought it advisable to attach them still more strongly to his person before he ventured to deprive the people of their power in the commonwealth. He therefore contented himself with repealing the Sulpician laws, and enacting that no matter should in future be brought before the people without the previous sanction of a senatusconsultum; for the statement of Appian (B. C. i. 59) that he now abolished the Comitia tributa, and filled up the members of the senate, is evidently erroneous, and refers to a later time. It appears, however, that he attempted at this time to give some relief to debtors by a lex unciaria, but the nature of which relief is uncertain from the mutilated condition of the passage in Festus (s. v.) who is the only writer that make mention of this lex. Sulla sent forward his legions to Capua, that they might be ready to embark for Greece, but he himself remained in Rome till the consuls were elected for the following year. He recommended to the people Nonius, his sister's son, and Serv. Sulpicius. His candidates, however, were rejected, and the choice fell on Cn. Octavius, who belonged to the aristocratical party, but was a weak and irresolute man, and on L. Cinna, who was a professed champion of the popular side. Sulla did not attempt to oppose their election; to have recalled his legions to Rome would have been a dangerous experiment when the soldiers were so eager for the spoils of the East; and he therefore professed to be pleased that the people made use I of the liberty he had granted them. He, however, took the vain precaution of making Cinna promise that he would make no attempt to disturb the existing order of things; but one of Cinna's first acts was to induce the tribune M. Virgilius to bring an accusation against Sulla as soon as his year of office had expired. Sulla, without paying any attention to this accusation, quitted Rome at the beginning of b. c. 87, and hastened to his troops at Capua, where he embarked for Greece, in order to carry on the war against Mithridates. For the next four years Sulla was engaged in the prosecution of this war, the history of which is given under Mithridates VI and his general Archelaus, and may therefore be dismissed here with a few words. Sulla landed at Dyrrhachium, and forthwith marched against Athens, which had become the head-quarters of the Mithridatic cause in Greece. After a long and obstinate siege, Athens was taken by storm on the 1st of March in the following year, b. c. 86; and in consequence of the insults which Sulla and his wife Metella had received from the tyrant Aristion, the city was given up to rapine and plunder. He next obtained possession of the Peiraeeus, which had been defended by Archelaus. Meantime Mithridates had sent fresh reinforcements to Archelaus, who concentrated all his troops in Boeotia. Sulla advanced against him, and defeated him in the neighbourhood of Chaeroneia with such enormous loss, that out of the 120,000 men with whom Archelaus had opened the campaign, he is said to have assembled only 10,000 at Chalcis in Euboea, where he had taken refuge. But while Sulla was carrying on the war with such success in Greece, his enemies had obtained the upper hand in Italy. The consul Cinna, who had been driven out of Rome by his colleague Octavius, soon after Sulla's departure from Italy, had entered it again with Marius at the close of the year. Both Cinna and Marius were appointed consuls b. c. 86, all the regulations of Sulla were swept away, his friends and adherents murdered, his property confiscated, and he himself declared a public enemy. It has frequently been made a subject of panegyric upon Sulla that he still continued to prosecute the war with Mithridates under these circumstances, and preferred the subjugation of the enemies of Rome to the gratification of his own revenge. But it must be recollected that an immediate peace with Mithridates would have discontented his soldiers; while by bringing the war to an honourable conclusion, he gratified his troops by plunder, attached them more and more to his person, and at the same time collected from the conquered cities vast sums of money for the prosecution of the war against his enemies in Italy. At the same time it is an undoubted proof of his sagacity and forethought that he knew how to bide his time. Most other men in his circumstances would have hurried back to Italy at once to crush their enemies, and thus have ruined themselves. Marius died seventeen days after he had entered upon his consulship, and was succeeded in the office by L. Valerius Flaccus, who was sent into Asia that he might prosecute the war at the same time against Mithridates and Sulla. Flaccus was murdered by his troops at the instigation of Fimbria, who now assumed the command, and who gained several victories over the generals of Mithridates in Asia, in b. c. 85. About the same time the new army, which Mithridates had again sent to Archelaus in Greece, was again defeated by Sulla in the neighbourhood of Orchomenus. These repeated disasters made Mithridates anxious for peace, but it was not granted by Sulla till the following year, b. c. 84, when he had crossed the Hellespont in order to carry on the war in that country. Sulla was now at liberty to turn his arms against Fimbria, who was with his army at Thyateira. The name of Sulla carried victory with it. The troops of Fimbria deserted their general, who put an end to his own life. Sulla now prepared to return to Italy. After exacting enormous sums from the wealthy cities of Asia, he left his legate, L. Licinius Murena, in command of the province of Asia, with two legions, and set sail with his own army to Athens. While preparing for his deadly struggle in Italy, he did not lose his interest in literature. He carried with him from Athens to Rome the valuable library of Apellicon of Teos, which contained most of the works of Aristotle and Theophrastus. [Apellicon.] During his stay at Athens, Sulla had an attack of gout, of which he was cured by the use of the warm springs of Aedepsus in Euboea. As soon as he recovered, he led his army to Dyrrhachium, and from thence crossed over to Brundusium in Italy.

Sulla landed at Brundusium in the spring of b. c. 83, in the consulship of L. Scipio and C. Norbanus. During the preceding year he had written to the senate, recounting the services he had rendered to the commonwealth from the time of the Jugurthine war down to the conquest of Mithridates, complaining of the ingratitude with which he had been treated, announcing his speedy return to Italy, and threatening to take vengeance upon his enemies and those of the republic. The senate, in alarm, sent an embassy to Sulla to endeavour to bring about a reconciliation between him and his enemies, and meantime ordered the consuls Cinna and Carbo to desist from levying troops, and making further preparations for war. Cinna and Carbo gave no heed to this command; they knew that a reconciliation was impossible, and resolved to carry over an army to Dalmatia, in order to oppose Sulla in Greece; but after one detachment of their troops had embarked, the remaining soldiers rose in mutiny, and murdered Cinna. The Marian party had thus lost their leader, but continued nevertheless to make every preparation to oppose Sulla, for they were well aware that he would never forgive them, and that their only choice lay between victory and destruction. Besides this the Italians were ready to support them, as these new citizens feared that Sulla would deprive them of the rights which they had lately obtained after so much bloodshed. The Marian party had every prospect of victory, for their troops far exceeded those of Sulla. According to Velleius Paterculus, they had 200,000 men in arms, while Sulla landed at Brundusium with only 30,000, or at the most 40,000 men. (Veil. Pat. ii. 24; Appian, B. C. i. 79.) But on the other hand, the popular party had no one of sufficient influence and military reputation to take the supreme command in the war; their vast forces were scattered about Italy, in different armies, under different generals; the soldiers had no confidence in their commanders, and no enthusiasm in their cause; and the consequence was, that whole hosts of them deserted to Sulla on the first opportunity. Sulla's soldiers, on the contrary, were veterans, who had frequently fought by each other's side, and had acquired that confidence in themselves and in their general which frequent victories always give to soldiers. Still if the Italians had remained faithful to the cause of the Marian party, Sulla would hardly have conquered, and therefore one of his first cares after landing at Brundusium was to detach them from his enemies. For this purpose he would not allow his troops to do any injury to the towns or fields of the Italians in his march from Brundusium through Calabria and Apulia, and he formed separate treaties with many of the Italian towns, by which he secured to them all the rights and privileges of Roman citizens which they then enjoyed. Among the Italians the Samnites continued to be the most formidable enemies of Sulla. They had not yet received the Roman franchise, because they had continued in arms down to this time, and they now joined the Marian party, not simply with the design of se- curing the supremacy for the latter, but with the hope of conquering Rome by their means, and then destroying for ever their hated oppressor. Thus this civil war became merely another phase of the Marsic war, and the struggle between Rome and Samnium for the supremacy of the peninsula was renewed after the subjection of the latter for more than two hundred years.

Sulla marched from Apulia into Campania without meeting with any resistance. It was in the latter country that he gained his first victory over the consul Norbanus, who was defeated with great loss, and obliged to take refuge in Capua. His colleague Scipio, who was at no great distance, willingly accepted a truce which Sulla offered him, although Sertorius warned him against entering into any negotiations, and his caution was justified by the event. By means of his emissaries Sulla seduced the troops of Scipio, who at length found himself deserted by all his soldiers, and was taken prisoner in his tent. Sulla, however, dismissed him uninjured. On hearing of this Carbo is said to have observed "that he had to contend in Sulla both with a lion and a fox, but that the fox gave him more trouble." Many distinguished Romans meantime had taken up arms on behalf of Sulla. Cn. Pompey had levied three legions for him in Picenum and the surrounding districts; and Q. Metellus Pius, M. Crassus, M. Lucullus, and several others offered their services as legates. It was not, however, till the following year, b. c. 82, that the struggle was brought to a decisive issue. The consuls of this year were Cn. Papirius Carbo and the younger Marius; the former of whom was entrusted with the protection of Etruria and Umbria, while the latter had to guard Rome and Latium. Sulla appears to have passed the winter at Campania. At the commencement of spring he advanced against the younger Marius, who had concentrated all his forces at Sacriportus, and defeated him with great loss. Marius took refuge in Praeneste, where he had previously deposited his military stores, and a great quantity of gold and silver which he had brought from the Capitol and other temples at Rome. Sulla followed him to Praeneste, and after leaving Q. Lucretius Ofella with a large force to blockade the town and compel it to a surrender by famine, he marched with the main body of his army to Rome. Marius was resolved not to perish unavenged, and accordingly before Sulla could reach Rome, he sent orders to L. Damasippus, the praetor, to put to death all his leading opponents. His orders were faithfully obeyed, Q. Mucins Scaevola, the pontifex maximus and jurist, P. Antistius, L, Domitius, and many other distingished men were butchered and their corpses thrown into the Tiber. Sulla entered the city without opposition; Damasippus and his adherents had previously withdrawn, and repaired to Carbo in Etruria. Sulla marched against Carbo, who had been previously opposed by Pompeius and Metellus. The history of this part of the war is involved in great obscurity. Carbo made two efforts to relieve Praeneste, but failed in each; and after fighting with various fortune against Pompey, Metellus, and Sulla, he at length embarked for Africa, despairing of further success in Italy. [For details see Carbo, No. 7.] Meantime Rome had nearly fallen into the hands of the enemy. The Samnites and Lucanians under Pontius Telesinus and L. Lamponius, after attempting to relieve Praeneste, resolved to march straight upon Rome, which had been left without any army for its protection. Sulla barely arrived in time to save the city. The battle was fought before the Colline gate; it was long and obstinately contested; the contest was not simply for the supremacy of a party; the very existence of Rome was at stake, for Telesinus had declared that he would raze the city to the ground. The left wing where Sulla commanded in person was driven off the field by the vehemence of the enemy's charge; but the success of the right wing, which was commanded by Crassus, enabled Sulla to restore the battle, and at length gain a complete victory. Fifty thousand men are said to have fallen on each side (Appian, B. C. i, 93). All the most distinguished leaders of the enemy either perished in the engagement or were taken prisoners and put to death. Among these was the brave Samnite Pontius Telesinus, whose head was cut off and carried under the walls of Praeneste, thereby announcing to the younger Marius that his last hope of succour was gone. To the Samnite prisoners Sulla showed no mercy. He was resolved to root out of the peninsula those heroic enemies of Rome. On the third day after the battle he collected all the Samnite and Lucanian prisoners in the Campus Martins, and ordered his soldiers to cut them down. The dying shrieks of so many victims frightened the senators, who had been assembled at the same time by Sulla in the temple of Bellona; but he bade them attend to what he was saying and not mind what was taking place outside, as he was only chastising some rebels, and he then quietly proceeded to finish his discourse. Praeneste surrendered soon afterwards. The Romans in the town were pardoned; but all the Samnites and Praenestines were massacred without mercy. The younger Marius put an end to his own life [Marius, No. 2]. The war in Italy was now virtually at an end, for the few towns which still held out had no prospect of offering any effectual opposition, and were reduced soon afterwards. In other parts of the Roman world the war continued still longer, and Sulla did not live to see its completion. The armies of the Marian party in Sicily and Africa were subdued by Pompey in the course of b. c. 82 ; but Sertorius in Spain continued to defy all the attempts of the senate to crush him, till his cowardly assassination by Perperna in b. c. 72. [Sertorius.]

Sulla was now master of Rome. He had not commenced the civil war, but had been driven to it by the mad ambition of Marius. His enemies had attempted to deprive him of the command in the Mithridatic war which had been legally conferred upon him by the senate; and while he was fighting the battles of the republic they had declared him a public enemy, confiscated his property, and murdered the most distinguished of his friends and adherents. For all these wrongs, Sulla had threatened to take the most ample vengeance; and he more than redeemed his word. He resolved to extirpate root and branch the popular party. One of his first acts was to draw up a list of his enemies who were to be put to death, which list was exhibited in the forum to public inspection, and called a Proscriptio. It was the first instance of the kind in Roman history. All persons in this list were outlaws who might be killed by any one with impunity, even by slaves; their property was confiscated to the state, and was to be sold by public auction; their children and grandchildren lost their votes in the comitia, and were excluded from all public offices. Further, all who killed a proscribed person, or indicated the place of his concealment, received two talents as a reward, and whoever sheltered such a person was punished with death. Terror now reigned, not only at Rome, but throughout Italy. Fresh lists of the proscribed constantly appeared. No one was safe; for Sulla gratified his friends by placing in the fatal lists their personal enemies, or persons whose property was coveted by his adherents. An estate, a house, or even a piece of plate was to many a man, who belonged to no political party, his death warrant; for although the confiscated property belonged to the state, and had to be sold by public auction, the friends and dependents of Sulla purchased it at a nominal price, as no one dared to bid against them. Oftentimes Sulla did not require the purchase-money to be paid at all, and in many cases he gave such property to his favourites without even the formality of a sale. Metella, the wife of the dictator, and Chrysogonus his freedman, P. Sulla, M. Crassus, Vettius, and Sex. Naevius are especially mentioned among those who received such presents; and handsome Roman matrons, as likewise actors and actresses, were favoured in the same manner. The number of persons who perished by the proscriptions is stated differently, but it appears to have amounted to many thousands. At the commencement of these horrors Sulla had been appointed dictator. As both the consuls had perished, he caused the senate to elect Valerius Flaccus interrex, and the latter brought before the people a rogatio, conferring the dictatorship upon Sulla, for the purpose of restoring order to the republic, and for as long a time as he judged to be necessary. Thus the dictatorship was revived after being in abeyance for more than 120 years, and Sulla obtained absolute power over the lives and fortunes of all the citizens. This was towards the close of b. c. 81. Sulla's great object in being invested with the dictatorship was to carry into execution in a legal manner the great reforms which he meditated in the constitution and the administration of justice, by which he hoped to place the government of the republic on a firm and secure basis. He had no intention of abolishing the republic, and consequently he caused consuls to be elected for the following year, b. c. 81, and was elected to the office himself in b. c. 80, while he continued to hold the dictatorship.

At the beginning of the following year, b. c. 81, Sulla celebrated a splendid triumph on account of his victory over Mithridates. In a speech which he delivered to the people at the close of the gorgeous ceremony, he claimed for himself the surname of Felix as he attributed his success in life to the favour of the gods. He believed himself to have been in particular under the protection of Venus, who had granted him victory in battle as well as in love. Hence, in writing to Greeks, he called himself Epaphroditus. All ranks in Rome bowed in awe before their master; and among other marks of distinction which were voted to him by the obsequious senate, a gilt equestrian statue was erected to his honour before the Rostra, bearing the inscription "Cornelio Sullae Imperatori Felici."

During the years b. c. 80 and 79, Sulla carried into execution his various reforms in the constitution, of which an account is given at the close of his life. But at the same time he adopted measures in order to crush his enemies more completely, and to consolidate the power of his party. These measures require a few words of explanation, as they did not form a part of his constitutional reforms, though they were intended for the support of the latter. The first of these measures has been already mentioned, namely the destruction of his enemies by the proscription. He appears to have published his list of victims immediately after the defeat of the Samnites and Lucanians at the Colline gate, without communicating, as Plutarch says (Sull. 31), with any magistrate; but when he was dictator he proposed a law in the comitia centuriata, which ratified his proscriptions, and which is usually called Lex Cornelia de Proscriptione or De Proscriptis. By this law it was enacted that all proscriptions should cease on the 1st of June, b. c. 81. The lex Valeria, which conferred the dictatorship upon Sulla, gave him absolute power over the lives of Roman citizens, and hence Cicero says he does not know whether to call the proscription law a lex Valeria or lex Cornelia. (Cic. pro Rosc. Am. 43, 44, de Leg. Agr. iii. 2.)

Another of Sulla's measures, and one of still more importance for the support of his power, was the establishment of military colonies throughout Italy. The inhabitants of the Italian towns, which had fought against Sulla, were deprived of the full Roman franchise which had been lately conferred upon them, and were only allowed to retain the commercium: their land was confiscated and given to the soldiers who had fought under him. Twenty-three legions (Appian, B. C. i. 100), or, according to another statement (Liv. Epit. 89), forty-seven legions received grants of land in various parts of Italy. A great number of these colonies was settled in Etruria, the population of which was thus almost entirely changed. These colonies had the strongest interest in upholding the institutions of Sulla, since any attempt to invalidate the latter would have endangered their newly-acquired possessions. But though they were a support to the power of Sulla, they hastened the fall of the commonwealth; an idle and licentious soldiery supplanted an industrious and agricultural population; and Catiline found nowhere more adherents than among the military colonies of Sulla. While Sulla thus established throughout Italy a population devoted to his interests, he created at Rome a kind of bodyguard for his protection by giving the citizenship to a great number of slaves belonging to those who had been proscribed by him. The slaves thus rewarded are said to have been as many as 10,000, and were called Cornelii after him as their patron.

Sulla had completed his reforms by the beginning of b. c. 79, and as he longed for the undisturbed enjoyment of his pleasures, he resolved to resign his dictatorship. Accordingly, to the general surprise he summoned the people, resigned his dictatorship, and declared himself ready to render an account of his conduct while in office. This voluntary abdication by Sulla of the sovereignty of the Roman world has excited the astonishment and admiration of both ancient and modern writers. But it is evident, as has been already remarked, that Sulla never contemplated, like Julius Caesar, the establishment of a monarchical form of government; and it must be recollected that he could retire into a private station without any fear that attempts would be made against his life or his institutions. The ten thousand Cornelii at Rome and his veterans stationed throughout Italy, as well as the whole strength of the aristocratical party, secured him against all danger. Even in his retirement his will was law, and shortly before his death, he ordered his slaves to strangle a magistrate of one of the towns in Italy, because he was a public defaulter.

After resigning his dictatorship, Sulla retired to his estate at Puteoli, and there surrounded by the beauties of nature and art he passed the remainder of his life in those literary and sensual enjoyments in which he had always taken so much pleasure. His dissolute mode of life hastened his death. A dream warned him of his approaching end. Thereupon he made his testament, in which he left L. Lucullus the guardian of his son. Only two days before his death, he finished the twenty-second book of his memoirs, in which, foreseeing his end, he was able to boast of the prediction of the Chaldaeans, that it was his fate to die after a happy life in the very height of his prosperity. He died in b. c. 78, in the sixtieth year of his age. The immediate cause of his death was the rupture of a blood-vessel, but some time before he had been suffering from the disgusting disease, which is known in modern times by the name of Morbus Pediculosus or Phthiriasis. Appian (B. C. i. 105) simply relates that he died of a fever. Zachariae, in his life of Sulla, considers the story of his suffering from phthiriasis as a fabrication of his enemies, and probably of the Athenians whom he had handled so severely; but Appian 's statement does not contradict the common account, which is attested by too many ancient writers to be rejected on the slender reasons that Zachariae alleges (Plut. Sull. 36; Plin. H. N. vii. 43. s. 44, xi. 33. s. 39, xxvi. 13. s. 86; Paus. i. 20. §7; Aurel. Vict. de Vir. Ill. 75). The senate, faithful to Sulla to the last, resolved to give him the honour of a public funeral. This was however opposed by the consul Lepidus, who had resolved to attempt the repeal of Sulla's laws; but Sulla's power continued unshaken even after his death. The veterans were summoned from their colonies, and Q. Catulus, L. Lucullus, and Cn. Pompey, placed themselves at their head. Lepidus was obliged to give way and allowed the funeral to take place without interruption. It was a gorgeous pageant. The magistrates, the senate, the equites, the priests, and the Vestal virgins, as well as the veterans, accompanied the funeral procession to the Campus Martins, where the corpse was burnt according to Sulla's own wish, who feared that his enemies might insult his remains, as he had done those of Marius, which had been taken out of the grave and thrown into the Anio at his command. It had been previously the custom of the Cornelia gens to bury and not burn their dead. A monument was erected to Sulla in the Campus Martius, the inscription on which he is said to have composed himself. It stated that none of his friends ever did him a kindness, and none of his enemies a wrong, without being fully repaid.

Sulla was married five times: — 1. To Ilia, for which name we ought perhaps to read Julia (Plut. Sull. 6). She bore Sulla a daughter, who was married to Q. Pompeius Rufus, the son of Sulla's colleague in the consulship in b. c. 88. [Pompeius, No. 8.] 2. To Aelia. 3. To Coelia, whom he divorced on the pretext of barrenness, but in reality in order to marry Caecilia Metella. 4. To Caecilia Metella, who bore him a son, who died before Sulla [see below, No. 6], and likewise twins, a son and a daughter. [No. 7.] 5. Valeria, who bore him a daughter after his death. [Valeria.]

Sulla's love of literature has been repeatedly mentioned in the preceding sketch of his life. He wrote a history of his own life and times, which is called Ὑπομνήματα or Memoirs by Plutarch, who has made great use of it in his life of Sulla, as well as in his biographies of Marius, Sertorius, and Lucullus. It was dedicated to L. Lucullus, and extended to twenty-two books, the last of which was finished by Sulla a few days before his death, as has been already related. This did not however complete the work, which was brought to a conclusion by his freedman Cornelius Epicadus, probably at the request of his son Faustus. (Plut. Sull. 6, 37, Lucull. 1; Suet. de Ill. Gramm. 12.) From the quotations in A. Gellius (i. 12, xx. 6) it appears that Sulla's work was written in Latin, and not in Greek, as Heeren maintains (Heeren, De Fontibus Plutarchi, p. 151, &c.; Krause, Vitae et Fragmenta Hist. Roman. p. 290, &c.) Sulla also wrote Fabulae Atellanae (Athen. vi. p. 261, c), and the Greek Anthology contains a short epigram which is ascribed to him. (Brunck, Lect. p. 267; Jacobs, Anth. Gr. vol. ii. p. 66, Anth. Pal. App. 91, vol. ii. p. 788.)

The chief ancient authority for Sulla's life is Plutarch's biography, which has been translated by G. Long, with some useful notes, London, 1844, where the reader will find references to most of the passages in Appian and other ancient writers who speak of Sulla. The passages in Sallust and Cicero, in which Sulla is mentioned, are given by Orelli in his Onomasticon Tullianum, pt. ii. p. 192. The two modern writers, who have written Sulla's life with most accuracy, are Zachariae, in his work entitled L. Cornelius Sulla, genannt der Glückliche, als Ordner des Römischen Freystaates, Heidelberg, 1834, and Drumann, in his Geschichte Roms, vol. ii. p. 429, &c. The latter writer gives the more impartial account of Sulla's life and character; the former falls into the common fault of biographers in attempting to apologise for the vices and crimes of the subject of his biography.

THE LEGISLATION OF SULLA.

[edit]All the reforms of Sulla were effected by means of Leges, which were proposed by him in the comitia centuriata and enacted by the votes of the people. It is true that the votes of the people were a mere form, but it was a form essential to the preservation of his work, and was maintained by Augustus in his legislation. The laws proposed by Sulla are called by the general name of Leges Corneliae, and particular laws are designated by the name of the particular subject to which they relate, as Lex Cornelia de Falsis, Lex Cornelia de Sicariis, &c. These laws were all passed during the time that Sulla was dictator, that is, from the end of b. c. 82 to b. c. 79, and most of them in all probability during the years b. c. 81 and 80. It is impossible to determine in what order they were proposed, nor is it material to do so. They may be divided into four classes, laws relating to the constitution, to the ecclesiastical corporations, to the administration of justice, and to the improvement of public morals. Their general object and design was to restore, as far as possible, the ancient Roman constitution, and to give again to the senate and the aristocracy that power of which they had been gradually deprived by the leaders of the popular party. It did not escape the penetration of Sulla that many of the evils under which the Roman state was suffering, arose from the corruption of the morals of the people; and he therefore attempted in his legislation to check the increase of crime and luxury by stringent enactments. The attempt was a hopeless one, for vice and immorality pervaded alike all classes of Roman citizens, and no laws can restore to a people the moral feelings which they have lost. Sulla has been much blamed by modern writers for giving to the Roman state such an aristocratical constitution; but under, the circumstances in which he was placed he could not well have done otherwise. To have vested the government in the mob of which the Roman people consisted, would have been perfect madness; and as he was not prepared to establish a monarchy, he had no alternative but giving the power to the senate. His constitution did not last, because the aristocracy were thoroughly selfish and corrupt, and exercised the power which Sulla had entrusted to them only for their own aggrandisement and not for the good of their country. Their shameless conduct soon disgusted the provinces as well as the capital; the people again regained their power, but the consequence was an anarchy and not a government; and as neither class was fit to rule, they were obliged to submit to the dominion of a single man. Thus the empire became a necessity as well as a blessing to the exhausted Roman world. Sulla's laws respecting criminal jurisprudence were the most lasting and bear the strongest testimony to his greatness as a legislator. He was the first to reduce the criminal law of Rome to a system; and his laws, together with the Julian laws, formed the basis of the criminal Roman jurisprudence till the downfal of the empire.

In treating of Sulla's laws we shall follow the fourfold division which has been given above.

I. Laws relating to the Constitution. — The changes which Sulla introduced in the comitia and the senate, first call for our attention. The Comitia Tributa, or assemblies of the tribes, which originally possessed only the power to make regulations respecting the local affairs of the tribes, had gradually become a sovereign assembly with legislative and judicial authority. Sulla deprived them of their legislative and judicial powers, as well as of their right of electing the priests, which they had also acquired. He did not however do away with them entirely, as might be inferred from the words of Appian (B. C. i. 59); but he allowed them to exist with the power of electing the tribunes, aediles, quaestors, and other inferior magistrates. This seems to have been the only purpose for which they were called together; and all conciones of the tribes, by means of which the tribunes had exercised a powerful influence in the state, were strictly forbidden by Sulla. (Cic. pro Cluent. 40.)

The Comitia Centuriata, on the other hand, were allowed to retain their right of legislation unimpaired. He restored however the ancient regulation, which had fallen into desuetude, that no matter should be brought before them without the previous sanction of a senatusconsultum (Appian, B. C. i. 59); but he did not require the confirmation of the curiae, as the latter had long ceased to have any practical existence. Göttling supposes that the right of provocatio or appeal to the comitia centuriata was done away with by Sulla, but the passage of Cicero (Cic. Verr. Act. i. 13), which he quotes in support of this opinion, is not sufficient to prove it.

The Senate had been so much reduced in numbers by the proscriptions of Sulla, that he was obliged to fill up the vacancies by the election of three hundred new members. These however were not appointed by the censors from the persons who had filled the magistracies of the state, but were elected by the people. Appian says (B. C. i. 100) that they were elected by the tribes. Most modern writers think that we are not to understand by this the comitia tributa, but the comitia centuriata, which voted also according to tribes at this time; but Göttling observes that as the senators were regarded by Sulla as public officers, there is no difficulty in supposing that they were elected by the comitia tributa as the inferior magistrates were. However this may be, we know that these three hundred were taken from the equestrian order. (Appian, l. c.; Liv. Epit. 89.) This election was an extraordinary one, and was not intended to be the regular way of filling up the vacancies in the senate; for we are expressly told that Sulla increased the number of quaestors to twenty, that there might be a sufficient number for this purpose (Tac. Ann. xi. 32.) It was not necessary for Sulla to make any alteration respecting the duties and functions of the senate, as the whole administration of the state was in their hands; and he gave them the initiative in legislation by requiring a previous senatusconsultum respecting all measures that were to be submitted to the comitia, as is stated above. One of the most important of the senate's duties was the appointment of the governors of the provinces. By the Lex Sempronia of C. Gracchus, the senate had to determine every year before the election of the consuls the two provinces which the consuls should have (Cic. de Prov. Cons. 2, 7; Sall. Jug. 27); but as the imperium was conferred only for a year, the governor had to leave the province at the end of that time, unless his imperium was renewed. Sulla in his law respecting the provinces (de Provinciis ordinandis) did not make any change in the Sempronian law respecting the distribution of the provinces by the senate; but he allowed the governor of a province to continue to hold the government till a successor was appointed by the senate, and enacted that he should continue to possess the imperium till he entered the city, without the necessity of its being renewed annually (comp. Cic. ad Fam. i. 9. §12). The time during which the government of a province was to be held, thus depended entirely upon the will of the senate. It was further enacted that as soon as a successor arrived in the province, the former governor must quit it within thirty days (Cic. ad Fam. iii. 6); and the law also limited the expenses to which the provincials were put in sending embassies to Rome to praise the administration of their governors. (Cic. ad Fam. iii. 8, 10.)

With respect to the magistrates, Sulla renewed the old law, that no one should hold the praetorship before he had been quaestor, nor the consulship before he had been praetor (Appian, B. C. i. 100; Cic. Phil. xi. 5) ; nor did he allow of any deviation from this law in favour of his own party, for when Q, Lucretius Ofella, who had taken Praeneste, presuming upon his services, offered himself as a candidate for the consulship, without having previously held the offices of quaestor and praetor, he was assassinated in the forum by the order of the dictator. Sulla also re-established the ancient law, that no one should be elected to the same magistracy till after the expiration of ten years. (Appian, B. C. i. 101; comp. Liv. vii. 42, x. 31.)

Sulla increased the number of Quaestors from eight to twenty (Tac. Ann. xi. 22), and that of the Praetors from six to eight. Pomponius says (De Orig. Juris, Dig. 1. tit. 2. s. 32) that Sulla added four new praetors, but this appears to be a mistake, since Julius Caesar was the first who increased their number to ten. (Suet. Caes. 41; Dion Cass. xlii. 51.) This increase in the number of the praetors was necessary on account of the new quaestiones, established by Sulla, of which we shall speak below.

One of the most important of Sulla's reforms related to the tribunate. It is stated in general by the ancient writers, that Sulla deprived the tribunes of the plebs of all real power (Vell. Pat. ii. 30; Appian, B. C. i. 100; Cic. de Leg. iii. 9; Liv. Epit. 89); but the exact nature of his alterations is not accurately stated. It appears certain, however, that he deprived the tribunes of the right of proposing a rogation of any kind whatsoever to the tribes (Liv. Epit. 89), or of impeaching any person before them, inasmuch as he abolished altogether the legislative and judicial functions of the tribes, as has been previously stated. The tribunes also lost the right of holding conciones (Cic. pro Cluent. 40), as has likewise been shown, and thus could not influence the tribes by any speeches. The only right left to them was the Intercessio. It is, however, uncertain to what extent the right of Intercessio extended. It is hardly conceivable that Sulla would have left the tribunes to exercise this the most formidable of all their powers without any limitation; and that he did not do so is clear from the case of Q. Opimius, who was brought to trial, because, when tribune of the plebs, he had used his intercessio in violation of the Lex Cornelia (Cic. Verr. i. 60). Cicero says (de Leg. iii. 9) that Sulla left the tribunes only the potestas auxilii ferendi; and from this we may infer, in connection with the case of Opimius, that the Intercessio was confined to giving their protection to private persons against the unjust decisions of magistrates, as, for instance, in the enlisting of soldiers. Caesar, it is true, states, in general, that Sulla left to the tribunes the right of intercessio, and he leaves it to be inferred in particular that Sulla allowed them to use their intercessio in reference to senatusconsulta (Caes. B. C. i. 5, 7); but it is not impossible, as Becker has suggested, that Caesar may have given a false interpretation of the right of intercessio granted by Sulla, in order to justify the course he was himself adopting. (Becker, Handbuch der Röm. Alterthümer, vol. ii. pt. ii. p. 290). To degrade the tribunate still lower, Sulla enacted, that whoever had held this office forfeited thereby all right to become a candidate for any of the higher curule offices, in order that all persons of rank, talent, and wealth, might be deterred from holding an office which would be a fatal impediment to rising any higher in the state. (Appian, B. C. i. 100; Ascon. in Cornel. p. 78, ed. Orelli.) The statement that Sulla required persons to be senators before they could become tribunes (Appian, l. c.), is explained by the circumstance that the quaestorship and the aedileship, which usually preceded the tribunate gave admission to the senate; and it would therefore appear that Sulla required all persons to hold the quaestorship before the tribunate.

II. Laws relating to the Ecclesiastical Corporations. — Sulla repealed the Lex Domitia, which gave to the comitia tributa the right of electing the members of the great ecclesiastical corporations, and restored to the latter the right of co-optatio or self-election. At the same time he increased the number of pontiffs and augurs to fifteen respectively (Dion Cass, xxxvii. 37; Liv. Epit. 89). It is commonly said that Sulla also increased the number of the keepers of the Sibylline books from 'ten to fifteen; and though we have no express authority for this statement (for the passage of Servius, ad Virg. Aen. vi. 73, does not prove it), it is probable that he did, as we read of Quindecemviri in the time of Cicero (ad Fam. viii. 4) instead of decemviri as previously.

III. Laws relating to the Administration of Justice. — Sulla established permanent courts for the trial of particular offences, in each of which a praetor presided. A precedent for this had been given by the Lex Calpurnia of the tribune L. Calpurnius Piso, in b. c. 149, by which it was enacted that a praetor should preside at all trials for repetundae during his year of office. This was called a Quaestio Perpetua, and nine such Quaestiones Perpetuae were established by Sulla, namely, De Repetundis, Majestatis, De Sicariis et Veneficis, De Parricidio, Peculatus, Ambitus, De Nummis Adulterinis, De Falsis or Testamentaria, and De Vi Publica. Jurisdiction in civil cases was left to the praetor peregrinus and the praetor urbanus as before, and the other six praetors presided in the Quaestiones; but as the latter were more in number than the praetors, some of the praetors took more than one quaestio, or a judex quaestionis was appointed. The praetors, after their election, had to draw lots for their several jurisdictions. Sulla enacted that the judices should be taken exclusively from the senators, and not from the equites, the latter of whom had possessed this privilege, with a few interruptions, from the law of C. Gracchus, in b. c. 123. This was a great gain for the aristocracy; since the offences for which they were usually brought to trial, such as bribery, malversation, and the like, were so commonly practised by the whole order, that they were, in most cases, nearly certain of acquittal from men who required similar indulgence themselves. (Tac. Ann. xi. 22; Vell. Pat. ii. 32; Cic. Verr. Act. i. 13, 16; comp. Dictionary of Antiquities, art. Judex.)

Sulla's reform in the criminal law, the greatest and most enduring part of his legislation, belongs to a history of Roman law, and cannot be given here. For further information on this subject the reader is referred to the Dict. of Antiq. art. Leges Corneliae.

IV. Laws relating to the Improvement of public Morals — Of these we have very little information. One of them was a Lex Sumtuaria, which enacted that not more than a certain sum of money should be spent upon entertainments, and also restrained extravagance in funerals, (Gell. ii. 24; Macrob. Sat. ii. 13; Plut. Sull. 35). There was likewise a law of Sulla respecting marriage (Plut. l. c.; comp. Lyc. c. Sull. 3), the provisions of which are quite unknown, as it was probably abrogated by the Julian law.

The most important modern works on Sulla's legislation are — Vockostaert, De L. Cornelio Sulla legislatore, Lugd. Bat. 1816; Zachariae, L. Cornelius Sulla, &c., Heidelb. 1834, 2 vols., the second volume of which treats of the legislation; Wittich, De Reipublicae Romanae ea forma, qua L. Cornelius Sulla totam rem Romanam commutavit, Lips. 1834; Ramshorn, De Reip. Rom. ea forma, qua L. C. S. totam rem Rom. commutavit. Lips. 1835; Göttling, Geschichte der Römischen Staatsverfassung, pp. 459 — 474; Drumann, Geschichte Roms, vol. ii. pp. 478—494.

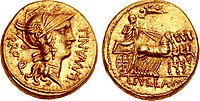

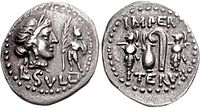

There are several coins of the dictator Sulla, a few specimens of which are annexed. The first coin contains on the obverse the head of the dictator, and on the reverse that of his colleague in his first consulship, Q. Pompeius Rufus. The coin was probably struck by the son of Q. Pompeius Rufus, who was tribune of the plebs in b. c. 52 [Pompeius, No. 9], in honour of his grandfather and father. The second coin was also probably struck by the tribune of b. c. 52. The third and fourth coins were struck in the lifetime of the dictator. The third has on the obverse the head of Pallas, with manli. proq., and on the reverse Sulla in a quadriga, with l. sulla imp., probably with reference to his splendid triumph over Mithridates. The fourth coin has on the obverse the head of Venus, before which Cupid stands holding in his hand the branch of a palm tree, and on the reverse a guttus and a lituus between two trophies, with imper. iteru(m). The head of Venus is placed on the obverse, because Sulla attributed much of his success to the protection of this goddess. Thus we are told by Plutarch (Sull. 34) that when he wrote to Greeks he called himself Epaphroditus, or the favourite of Aphrodite or Venus, and also that he inscribed on his trophies the names of Mars and Victorv, and Venus (Sull. 19). (Comp. Eckhel, vol. v. pp. 190, 191.)